Tibetan Buddhism as a World Religion: Global Networking and its Consequences

by Geoffrey Samuel

1.Introduction

The rapidly increasing connectedness of world societies has meant that traditional religions face both a threat and an opportunity. The threat is of the corrosive and destructive effect of contact with modes of thinking that reject and undermine their basic postulates. The opportunity is provided by large numbers of potential converts who have not previously been accessible to them. Buddhism, particularly in its Tibetan variety, has proved one of the most successful of traditional religions in adapting to this new global context, and I begin by asking why this is.

Several reasons may be suggested. As far as Buddhism in general is concerned, we can consider for example the ease with which Buddhist philosophy (Mahayana in particular) can be viewed as harmonious with contemporary science, and the success with which Buddhism has been presented as an essentially non-violent, non-hierarchical and ecologically friendly tradition. [1]

In relation to Tibetan Buddhism specifically, we might note the great internal variety of Tibetan religion, which can seem to have something for almost every religious need from healing rituals and prosperity magic to profound meditative experiences and subtle philosophical argument. Another key issue, however, is undoubtedly the presence of large numbers of teachers of Tibetan-style Buddhism in the shape of the refugee lamas who left Tibet in 1959 and the following years.

In a recent article, Jan Nattier has suggested that American Buddhism may be classified into three general categories. These are "Elite Buddhism," characterized by the generally elite groups within US society who constitute its practitioners and finance its importation; "Evangelical Buddhism," where there is an active missionary orientation on the part of Eastern Buddhists; and "Ethnic Buddhism," imported as part of their cultural baggage by Asians from Buddhist societies settling in America (Nattier 1995). In Nattier's terms, there is little doubt that Tibetan Buddhism in the West is "Elite Buddhism" rather than "Evangelical Buddhism," a religion driven by the Western desire to be converted rather than the Asian desire to missionize.

Indeed, Nattier only has one real example of Evangelical Buddhism. This is Soka Gakkai, which is, doubtless not coincidentally, one of the few active and expansionist forms of Buddhism within Asian societies which are economically competitive with the West and so able to finance a large-scale missionary operation. Yet if, with Tibetan Buddhism, the pull comes from the Western side, there is, at the least, an active willingness to co-operate among the Tibetans themselves which is a significant part of the process.

For Tibetan lamas, the cultivation of their new global audience is both a religious duty and a sensible pragmatic strategy, and their activities in Western societies form only part of a larger pattern. In recent years some of these teachers have developed extensive international networks, including "Dharma centres" in Western and Eastern Europe, the USA, Latin America and overseas Chinese communities, as well as Tibetan refugees in India and Nepal, the rebuilt Buddhist communities of Tibet itself, and societies such as the Mongolian People's Republic, Tuva or Buryatia where Tibetan Buddhism is re-emerging after a long period of suppression. In this paper I want to look particularly at these lamas and their networks, and to ask how far this is an extension of a traditional pattern within Tibetan Buddhism and to what extent it represents a new development. I also want to consider what effect the growth of these networks is having on Tibetan Buddhism itself.

2. Tibetan Buddhism in the Pre-Modern Period

First, however, we need some idea of how Tibetan Buddhism operated in its traditional pre-modern context, by which I mean essentially until around 1950. In a recent book, Civilized Shamans, I gave an overall picture of Buddhism in Tibetan societies in pre-modern times. Rather than recapitulating that argument here in detail, I shall note a few significant points and refer you to my book for substantiation (Samuel 1993). I apologize to those of you for whom this is going over familiar ground.

An important starting point is the relatively decentralized nature of Tibetan societies. Despite popular images of the Dalai Lama as a "God King," Tibetan regimes were mostly weak or small-scale. They had little detailed control over people's lives, at any rate away from a few relatively centralized areas with large-scale estates farmed by peasant cultivators. The low population density, the relatively low productivity of high-altitude agriculture, the nomadic nature of much of the population, and the difficulties of communication around the plateau, all contributed to the maintenance of this pattern.

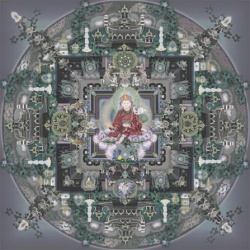

Consequently, Buddhism was also decentralized, and survived by catering to local needs. In Tibetan societies, these needs were typically for ritual services concerned with health and prosperity of agricultural or pastoral communities and with protection from malevolent spiritual forces. While Vajrayana (Tantric) Buddhism in Tibet retained an ideologically central orientation towards the achievement of Enlightenment, liberation from the sufferings of samsara, and the like, in practice much of the everyday activity of lamas and monks was taken up with the performance of Tantric ritual for this-worldly ends for the lay community. The contrast with Western orientations towards Buddhism is striking, but the Tibetan situation did perhaps help provide a pre-adaptation of Tibetan Buddhism for its later Western success in at least two respects: the wide variety of different paths and approaches, and the relatively fluid boundary between laity and the professionals compared to other Buddhist traditions.

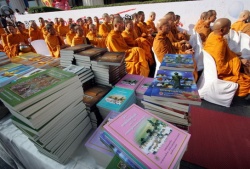

There was a large monastic population, if not perhaps as large as it sometimes suggested (my estimates suggest 10-12% of the male population in the centralized agricultural areas) but relatively few of these were either advanced scholars or advanced yogic practitioners. The central figures for the lay population were the much smaller number of lamas (a word corresponding to the Sanskrit guru but with an expanded range of meaning in the Tibetan context). These were teachers and leaders of monastic communities. They were often recognized reincarnations of past lamas, sometimes members of hereditary lama families, and they were generally expected to be competent magical ritual practitioners (hence the "civilized shamans" of my book title). Most of them were men, but there were some women. I shall return later to this question of gender.

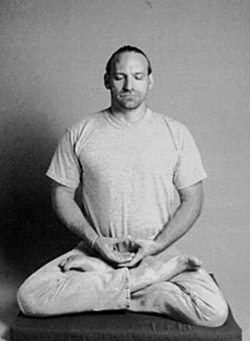

Lamas were not necessarily celibate monks or nuns, although in practice, in recent centuries, most of them were. The Tibetans continued the Indian Vajrayana idea of lay Tantric practice and there were communities of lay practitioners with varying degrees of separateness from lay life. Some of you may be familiar with a recent article by Robert Sharf arguing that the Western tendency to treat "experience" (meaning mystical or meditative experience) as central to the definition of Buddhism is a distortion of traditional Asian Buddhism, where the practice of meditation played little part in monastic life, let alone lay practice, until its reintroduction in recent years, largely as a result of the encounter with the West (Sharf 1995). Sharf's evidence comes mainly from Japan and the Theravadin societies. I find much of his argument convincing, but I think a good case can be made for the continuing importance of Tantric practice for a significant minority of both monastic and lay practitioners in Tibetan societies until modern times. The existence of this active practice tradition was to play an important part in the appropriation of Tibetan Buddhism by the West.

Tibetan lamas normally trained in a particular monastery of a particular tradition, and the relationship with their personal teachers (lamas) was of great importance. While, ideologically at least, obedience to the lama's instructions was of great importance, once a lama had become director of a separate monastic or lay community, he or she tended to have a great deal of autonomy. This is perhaps particularly true where, as is often the case with high-status reincarnate lamas, their principal personal teacher is someone who, however greatly he may be respected as a spiritual teacher, is not in his own right the head of a monastic institution. Each significant monastic or lay community (the standard Tibetan term, dgon pa, can refer to either) operated as a separate economic and political entity and tended to develop its own local and to some degree idiosyncratic traditions of ritual practice. Consequently, while it is customary to speak of the four main "schools," "orders," "traditions" or even "sects" of Tibetan Buddhism (five, if the Bon-po are included) these terms may imply a hierarchical structure and a degree of coherence and exclusivity which did not in fact exist.

Such hierarchical control as existed within the religious traditions was not in any case at the level of these four main "orders," except to a limited degree in the case of the largest order, the dGe-lugs-pa. The dGe-lugs-pa did have a formal head of a kind in the person of the Abbot of dGa'-ldan monastery, the dGa'-ldan Khri Rin-po-che, and also had an informal head in the person of the Dalai Lama or his regent. It is not at all clear, however, to what extent the dGa'-ldan Khri Rin-po-che could issue orders that would have any authority even among the three major dGe-lugs-pa monasteries of the Lhasa area. For practical purposes, the colleges (grwa tshang) within those monasteries were autonomous units, as were the hostels and the households of the various reincarnate lamas.

In the case of the other orders, the largest entity with a single head was a subdivision of the order, and in all cases individual monasteries had considerable autonomy. The unity of sub-orders and dGe-lugs-pa colleges seems often to have consisted in little more than that monasteries might perform many of the same rituals, study the same college textbooks, and send their lamas for training to the same central monastery, although I know of little research that addresses these issues directly. Ter Ellingson stressed some years ago in a study of monastic charters (bca' yig) that the monastery itself had a considerable degree of internal democracy (Ellingson 1990).

At the same time, the dGe-lugs-pa on the one hand and the non-dGe-lugs-pa orders on the other did have distinct and contrasting identities and bodies of shared teachings. For the non-dGe-lugs-pa traditions these were particularly associated with the teachers of the so-called Ris-med movement in Eastern Tibet from the late 19th centuries onwards. This cut across order, sub-order and monastic identities to create a network of teacher-disciple ties which increasingly linked rNying-ma-pa, bKa'-brgyud-pa and to some extent also Sa-skya-pa lamas.

The Dalai Lama as head of the Lhasa government could accept or withhold the recognition of a reincarnate lama, but his failure to recognize a lama was not necessarily regarded as final. Thus the failure of the Lhasa government to recognize the Zhwa-dmar-pa reincarnate lamas, the second-highest incarnate lineage of the Karma bKa'-brgyud-pa sub-order, from the late 18th century onwards, never seems to have been accepted by that sub-order, and in recent times Zhwa-dmar-pa lamas have again been recognized publicly. Similarly, while the Bhutanese government has attempted to prevent recognition of the Zhabs-drung Rin-po-che, formerly the Bhutanese head of state, since the establishment of the kingdom in 1907, it has had only limited success in doing so, and there are at least two lamas alive today with established claims to this title.

This combination of a rather weak hierarchical structure and the need for lay support to maintain monastic communities and build new ones meant there was something of a competitive and even entrepreneurial character to the activities of Tibetan lamas. Like tribal shamans, they were in a sense in competition for clients. Within the more centralized areas, the followings of monasteries might be relatively stable over generations, although there was always scope for a charismatic new lama to attract a following and build a community. At the edges, among partially-Tibetanized and part-Buddhist populations, the situation was more open and there was plenty of scope for missionary activity. Consequently, Tibetan Buddhism as a religious and cultural form gradually spread into new territories.

We think of Tibetan Buddhism as a "Tibetan" religion, which in part reflects the state of affairs in the 1950s when the Chinese takeover got under way. However, we should recall that in the early years of this century Tibetan Buddhism extended over a considerably larger population than that of culturally Tibetan people.

In particular, a large proportion of the Mongolian population of what is now the People's Republic of China, independent Mongolia, and Russia were Tibetan Buddhists. This includes the present-day Kalmyk and Buryat populations of the former Soviet Union, and also the Turkic population of Tuva. Tibetan Buddhist influence in these regions went back to the initial Tibetan-Mongol contact in the 13th century and particularly to the missionary activities of the dGe-lugs-pa tradition in the 16th centuries onwards. In North-East Tibet (Amdo) there were large dGe-lugs-pa monasteries where many Mongol Buddhists came to study, as well as a substantial Mongol population, so that Tibetan and Mongol Buddhist institutions tended to overlap. Tibetan mostly remained the language of instruction and the liturgical language within Mongolian Buddhism, although much of the canonical literature was translated into the Mongolian language.

There were also other partially Tibetanized groups, such as the Tu (Monguor) in Amdo, and the Naxi, Yi and others in Yunnan. Indigenous shamanic traditions remained alive among these populations. and there was often conflict (cf Heissig 1980 for the Mongols). Buddhism, however, was very much an active presence and part of a wider cultural network and regional identity.

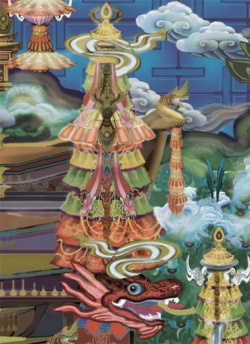

To this we should add the Tibetan Buddhist presence in China proper. Historically this was linked mainly to Manchu imperial patronage, as with the Yungho Kung in Beijing and its resident incarnate lama, the lCang-skya Hutuqtu. However, "Tibet" in the 20th century seems to have had an aura of magical power and mystic knowledge for some Chinese rather like that it had in the West, and Tibetan lamas were active in carrying out missionary activities in Chinese cities in the 1920s and 1930s (cf e.g. Blofeld 1972). Tibetan Buddhism was also important in Nepal, where the Newar people of the Kathmandu valley, who had a closely related Vajrayana Buddhist tradition, were in constant contact with Tibet on trading journeys. The northern fringe of Nepal, including the Sherpa region, is culturally Tibetan, and several of the hill peoples to the south (primarily the so-called Tamang groups and the Thakkali) have been partially Tibetanized.

These far-flung connections were associated with the regular journeys of Tibetan, Mongol, Newar and other traders along the long-distance trade routes between northern and eastern India, Sichuan, Yunnan, Nepal, Kashmir and beyond. Trade and pilgrimage were closely connected in the region, and these established routes also enabled students of Buddhism to move between central and peripheral regions.

Centre and periphery can be slightly misleading terms here if they suggest that Tibetan Buddhism in pre-modern times consisted of a simple radiation of Buddhist teachings from Lhasa and Central Tibet outwards. It is true that most of the monastic centres important in the early history of Tibetan Buddhism were in Central Tibet, and the major training centres of the dGe-lugs-pa in particular remained there. The more important training monasteries of the rNying-ma-pa and bKa'-brgyud-pa in modern times, however, were located in East Tibet, and the Sa-skya-pa also had large centres there. The dGe-lugs-pa too, with their Mongolian connections, had major establishments in both Khams and A-mdo (North-East Tibet) as well as in Mongol territory proper. Lamas from these superficially "peripheral" areas played a major role in Tibetan Buddhism in recent centuries. The Ris-med movement among the Sa-skya, bKa'-brgyud and rNying-ma was based in sDe-dge in Khams, and many of the leading dGe-lugs-pa scholars of the last two centuries came from Khams or A-mdo or were Mongols from further north or east. Such scholars might or might not come to study in Central Tibet as part of their training, and if they did they did not necessarily remain there for the whole of their careers. Tibetan Buddhism in recent centuries developed over a total field which encompassed the entire region of Tibetan population (except for the Islamicized regions in the extreme west) and much of the surrounding non-Tibetan population.

Within this regional presence, individual lamas and monasteries built up networks constituted in the first place by lama-student linkages. Tibetans might travel for long distances to study with a reputed lama or at a famous teaching centre, and would then take that lama's traditions of teaching and ritual practices as the basis for their own community should they found one (e.g. Stutchbury 1994). The network might encompass, over time, people from urban, peasant and nomadic backgrounds, from Tibetan, Mongol, or other ethnic backgrounds, and while the networks of centres developed in this way consisted, in practical terms, of independent units, they would continue to consult the original lama for guidance as long as he or she lived, and would probably maintain active links to their fellow centres for some time at least after the lama's death.

The regional presence of Tibetan Buddhism through large parts of East Asia began to disappear in the 1920s, with the Communist takeover in Siberian Russia and Mongolia. Buddhism and indigenous shamanism were initially tolerated but, by the 1930s, actively suppressed. Tibetan Buddhism as a living religion effectively disappeared until the 1980s in the then USSR and the Mongolian People's Republic. The destruction of Buddhism among the Tibetans themselves followed in the 1950s with the incorporation of Tibetan regions into the People's Republic of China. This took place in two stages, since the so-called Tibet Autonomous Region, comprising somewhat less than half the Tibetan population within the PRC, retained some autonomy from 1950 to 1959, whereas the Tibetan populations within the modern Chinese provinces of Sichuan, Qinghai, Yunnan and Gansu were directly incorporated into those Chinese provinces from 1950 onwards. In both regions, a period of limited toleration was followed, during the heyday of the Cultural Revolution in the 1970s, by active suppression and by large-scale destruction of Buddhist institutions. What was left of Tibetan and other Buddhist practice in China proper was also largely destroyed during this period.

3. The Survival of Tibetan Buddhism

As we all know, this did not mean the end of Tibetan Buddhism. Continuity and revival took place in several ways and in several stages.

First, there was the refugee community. Around 70,000 Tibetans are generally held to have left Tibet in 1959 and the immediately following years, and most of these settled in India and Nepal. Both countries, particularly India, provided generous facilities for settlement. The Dalai Lama and the remains of the Lhasa administration eventually settled down in the small town of Dharamsala in nothern India. Some of the refugees were relocated in large agricultural settlements, most of them in southern India, but many settled in Dharamsala and other northern Indian hill towns. The Dharamsala administration, while never officially given the status of government-in-exile by the Indian government, had considerable scope to organize refugee affairs. It established what was at least for the first couple of decades a largely autonomous school system within which Tibetan language and aspects of Tibetan culture could survive, and they assisted monastic refugees in reconstituting the major monastic institutions of Tibet in exile.

Within a few years, many of the major Tibetan monasteries, such as the constituent colleges of dGa'-ldan, Se-ra and 'Bras-spungs, the two Tantric Colleges from Lhasa, the rGyal-ba Karma-pa's monastery, and the head monastery of Sa-skya, had been recreated in India or Nepal. While the new institutions, in a very different economic environment, were not in a position to carry on the concentrated monastic training they had provided in Tibet, they were not short of new recruits, in part because the rigours of escape and early years in exile meant that there were many young children without other means of support.

In retrospect, this re-creation of Tibetan monastic institutions in exile is perhaps an even more remarkable achievement than it appeared at the time, and we can see how all subsequent developments within Tibetan Buddhism depended upon it. It is also an achievement which raises some interesting questions. Just why, in what were extraordinarily difficult circumstances, did things happen in this way? Why, in particular, did the various traditions retain so much separateness and individual identity? There were a few attempts at communities that shared different traditions, but they were, as far as I know, mostly minor and short-lived. [2] Even the agricultural settlements rapidly acquired a range of small separate temples and monastic communities for different sub-traditions; Bir in Himachal Pradesh when I went there in 1989 had 2000 people, and already had three separate small rNying-ma-pa monasteries along with several from other traditions. In part, these monasteries followed the lines of local and regional identities within the lay communities of the settlements.

Second, however total the destruction in Chinese-occupied territory, several traditionally Tibetan Buddhist areas were not directly affected. These were the culturally-Tibetan regions of northern India (Ladakh, Lahul, Spiti, Zanskar) and Nepal, the Indian protectorate of Sikkim (later incorporated into India) and the independent kingdom of Bhutan. Looking at the total field of Tibetan Buddhism in the 1950s, these were marginal areas or backwaters, but they did at least provide places of refuge for the initial waves of refugees, locations where monasteries could be re-established, and sources of support for refugee lamas.

This was particularly important for the non-dGe-lugs-pa traditions, since the Dharamsala adminstration inevitably was more concerned with the dGe-lugs-pa to which it had close traditional links. Thus Sikkim provided the location for the rGyal-ba Karma-pa's new monastery at Rumtek, and the Bhutanese state was initially very hospitable to the various Ris-med teachers, although less so as time went on to lay Tibetans. As for Nepal, the old Tibetan enclave at Bauddha by the 1990s had become the greatest single centre for the surviving non-dGe-lugs-pa traditions (Helffer 1993), with lesser concentrations elsewhere in the Valley such as at Swayambhunath and Pharphing.

4. Transmission to the West

The third context of survival was the transmission of Buddhism to the West. Unlike the two previous modes of survival, this involved the recruitment of an entirely new and culturally quite different following for the lamas.

Tibet had of course had had some contact with Western countries, especially Great Britain, throughout the first half of the 20th century, and the West provided an obvious direction to look for political support for Tibetan independence. The Dharamsala administration deliberately chose English as the main language for the refugee school system, and consciously cultivated Western support from the first years of exile. At the same time, the West offered a new field for conversion to Buddhism.

I am not sure how far this was carried out as a deliberate policy. In the early years, I am fairly sure that it was not. Most of the first lamas to come to the West did not come as missionaries, but as political refugees (as with the Kalmyk Mongolian lama Geshe Wangyal in New Jersey) or as university teachers or researchers (as with T.J. Norbu, the Dalai Lama's elder brother, at Bloomington, the Sa-skya lamas at Seattle, or Geshe Sopa at Madison, or Professor Namkhai Norbu at Naples). Other lamas came to the West initially to study at Western universities, as with the reincarnate lamas Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche and Sogyal Rinpoche, both subsequently important figures in the growth of Tibetan Buddhism in the West.

Some of these individuals may have had in mind the potential for missionary activity in the West, but I do not think that there was any concerted policy from Dharamsala to attract Western disciples. In fact, the Dharamsala administration in the late 1960s and early 1970s seemed quite taken by surprise by the influx of young Westerners wanting to study Buddhism, and it was only gradually that they provided classes and training through the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives at Dharamsala. Regular classes began at the Library in 1971, under the direction of Geshe Ngawang Dhargyay (1921-95). The Dharamsala administration were understandably more concerned with religious life among the refugee community, and the first Dharamsala-sponsored monastic centre in the West, that at Rikon in Switzerland, seems to have been intended primarily for Tibetan refugees in Switzerland, not for Westerners. [3]

Meanwhile, elsewhere in India and Nepal, other Westerners were forming links with individual refugee lamas, such as the rGyal-ba Karma-pa, Kalu Rinpoche, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, Lama Yeshe and Thubten Zopa Rinpoche, quite independently as far as I know from any plans by Dharamsala to missionize the Western world. In fact, what was to become the major dGe-lugs-pa Buddhist network in the West derived not from Dharamsala but from the small centre established in 1971 at Kopan, near Kathmandu, by Western followers of Lama Thubten Yeshe (1935-84) and his student, a young dGe-lugs-pa incarnate lama from Nepal, Thubten Zopa Rinpoche (b.1946). These two lamas met their first Western students in 1965 and by 1971 had settled at Kopan, where

due to demand, they began teaching Buddhist philosophy and meditation to increasing numbers of travellers, who in turn started groups and centers in their own countries. In 1975 Lama Yeshe named this fledgling network the Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition. Now, more than eighty centers and other activities make up the FPMT and it grows yearly. [4]

Although the FPMT] was eventually given Dharamsala approval, its origin, as far as I know, had nothing to do with Dharamsala. It is interesting that the initiative came from two lamas who had no immediate following among the Tibetans themselves. Lama Zopa was the reincarnation of the Lawudo Lama, a married rNying-ma tantric practitioner from Thami in Sherpa country, but he was trained in the dGe-lugs tradition which has no real presence among the Sherpas, whose Buddhism derives from the rNying-ma-pa tradition. There was no monastic community associated with Lama Zopa's previous incarnation, and in fact there seems to have been disagreement about his recognition as the Lawudo Lama for many years. [5] Lama Zopa and his teacher thus had no strong ties to any particular Tibetan community. They were free to respond to the growing interest from Western travellers in Nepal, and to develop a following among them. The difficulties of the refugee situation meant that there were quite a number of lamas in similarly isolated positions, for whom the acquisition of Western disciples was a natural move in both practical and Dharmic terms.

The late 1960s and 1970s was, of course, a period in Western history when many Westerners, particularly young people, were turning to the East for wisdom, and when travel to India and Nepal was for the first time relatively easy and inexpensive for people in Europe and the USA. It is hardly surprising that the refugee lamas should become an obvious resource. At the same time, one should not forget that generations of Western scholars and Buddhist enthusiasts had created much of the preconditions: the Theosophists, with their Himalayan masters, however illusory they might have proved to be; Sir John Woodroffe, whose work on Tantra, though mainly Hindu, included a text from the Cakrasamvara Tantra cycle; W.Y. Evans-Wentz, whose translations of The Tibetan Book of the Dead, The Life of Milarepa and other texts, with commentaries by Jung and others, were the first Tibetan texts to attain wide circulation in the West, Lama Anagarika Govinda, the lama of German origins who played an important part in development of Buddhism in Germany and whose books were widely read in the English-speaking world, the fake English lama Lobsang Rampa, and so on. Tibet was, at the very least, a recognizable label.

In the West itself, the first lamas to teach extensively to Westerners, in the 1960s onwards, were Geshe Wangyal, a director of the Kalmyk community in New Jersey, and Tarthang Tulku, who settled in Berkeley and built his Institute close by the University of California campus. Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, who initially came to study at Oxford, began teaching in the late 1960s in England, founded Samyê-Ling, the first Tibetan monastic centre in the West, in 1968, and moved to the USA in the early 1970s, where he built up what was at its height probably the largest single Tibetan Buddhist organization in the West.

Other lamas followed, many of them brought over by groups of Westerners who had become their disciples in India and Nepal. Some of the more senior lamas, such as rGyal-ba Karma-pa or Kalu Rinpoche, although they never settled in the West themselves, visited repeatedly and sent junior lamas from their traditions over to head centres in Western countries. Lamas who were present in the West in academic positions, such as Geshe Lhundup Sopa at Virginia, L.S. Dagyab in Bonn and Namkhai Norbu at Naples, found themselves increasingly encouraged to become teachers of Buddhism to Western disciples and shifted roles to a greater or lesser degree. Some Westerners became monks or nuns, though relatively few have remained in the monastic sangha; others undertook 3-year retreats or engaged with Tibetan Buddhist practice in other serious ways. By the 1990s, the numbers of Westerners involved in these various groups and centres, which form part, of course, of a wider spectrum including other kinds of Western Buddhist activity, were quite substantial, though rather difficult to estimate.

Gradually, Tibetan Buddhism has acquired a recognized presence within Western societies. The story is probably familiar at least in part to many of you, and I will not describe it at length here. What I would like to consider instead is the organizational context within which Tibetan Buddhism in the West is now situated, and the effects this has on the kind of Buddhist practice which has evolved.

5. The Evolution of Global Networks

The characteristic context, I would suggest, of Tibetan Buddhism in the West is that of a national or international network, generally centred around the teachings of a single individual lama. Among the larger ones are the FPMT, which I have already mentioned, now headed by Lama Zopa and the child-reincarnation of Lama Yeshe; the New Kadampa, in origin a break-away from the FPMT; the Shambhala network, deriving from Chögyam Trungpa's organization and now headed by his son; and the networks assocated with Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche (the Dzogchen Community) and Sogyal Rinpoche (Rigpa).

An important point about these networks is their international nature. Each of the major ones is spread across several Western countries, with a number of major and minor centres in each country. To varying degrees, they also have representation in Eastern Europe and in the European parts of the former Soviet Union, and in Japan and the overseas Chinese communities of Taiwan, Singapore and Malaysia.

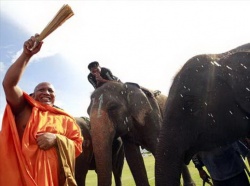

Many of them also have established connections with lamas and monasteries among the refugee Tibetan populations. Thus Sogyal Rinpoche's organization has close links with Dzogchen Monastery at the Kollegal Settlement near Mysore in South India. The reincarnate lama who is the head of this monastery, Dzogchen Rinpoche, is Sogyal Rinpoche's half-brother. Western students of Sogyal Rinpoche visit Kollegal and many of them attended the opening rituals of the new monastery there in January 1992. On this occasion, H.H. the Dalai Lama gave a series of rDzogs-chen empowerments deriving from the 5th Dalai Lama to an assembled gathering of Tibetans and Westerners.

In the early 1980s, with the end of the Cultural Revolution and of the very harsh anti-religious policies associated with it in Tibet, Buddhist practice gradually became possible again in the Chinese-controlled regions of Tibet. Many monasteries there have been partially rebuilt, and links have been re-established with refugee lamas, who have begun to revisit their communities in Tibet and, where possible, raise funding for reconstruction.

Western Buddhists have shown varying degrees of interest in Tibetan politics and in fund-raising for the Tibetans. My impression is that the fund-raising and political support groups, on the one hand, and the Dharma centres, on the other, have overlapping memberships, but that most Westerners are interested primarily in one kind of activity or the other, not in both. Lamas, too, vary, but the reincarnate lamas at least generally have monasteries back in Tibet who look to them for support, and even if they have no plans to go back there permanently in the present political situation, they clearly feel an obligation to do something for them. The international network thus generally has at least some links to the revived Buddhist communities in Chinese-controlled Tibet.

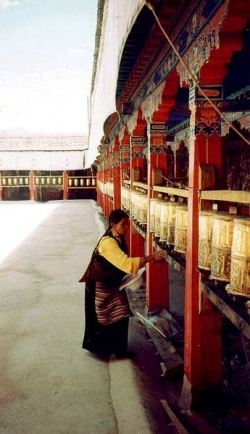

In recent years, as the Buddhist communities of Mongolia and the former Soviet Union have revived, lamas have expanded into these areas too. These regions have few surviving reincarnation lines of their own, but following the breakup of the Soviet Union they have become independent or semi-independent states with a traditional sympathy for Tibetan Buddhism. The Dalai Lama has been on enormously successful state visits to these societies, and a number of other lamas, such as Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche, have followed and begun to build up organizations in these regions.

Two tables (Tables 1 and 2) give a glimpse of the current form of these international structures. Table 1 is a listing of the network of Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche, as it was in mid-1995. Namkhai Norbu came to Italy in 1960 as a research associate to Professor Giuseppe Tucci. He became a professor at Naples University in 1964, teaching Tibetan and Mongolian studies, and only started teaching Buddhism to Western students some years later - I think in the mid to late 1970s.

[EUROPE]

Austria

Belgium

Denmark

Finland

France

Germany

Great Britain

Greece

Holland

Norway

Spain

Switzerland

[EASTERN EUROPE, WESTERN FSU]

Byelorussia

Estonia

Latvia

Lithuania

Poland

Russian Federation

Slovenia

Yugoslavia (Serbia)

[NORTH AMERICA]

[SOUTH AMERICA]

- Argentina

Peru

Venezuela

[ASIA]

Buryatia

Israel

Japan

Kalmykia

Malaysia

Nepal

Singapore

Thailand

[AFRICA]

South Africa

[AUSTRALASIA]

New Zealand

Table 1: DZOGCHEN COMMUNITY NETWORK, 1995

Countries listed are those where the Dzogchen Community has an active centre. Countries where there are regional centres (gar) are indicated by a star *. I have not listed Tibet, since this is not included as part of the list of centres I was working from, but Namkhai Norbu has close links to three Tibetan communities associated with his teaching lineage, and an active fund-raising and community development organization with several projects in Tibet.

The list is rather skeletal, but it illustrates some of the developments I have been discussing. It does not indicate the relative size of Namkhai Norbu's organization in the different countries. It is probably strongest, as you might expect, in Western Europe, where he first began to teach, and in the USA, where he has long had a number of active groups of students. The USA has several centres, and so do some of the European countries. Of the Asian groups, those in Nepal and Thailand are, I think, small groups of Westerners living semi-permanently in those countries, but those in Malaysia and Singapore are made up primarily of overseas Chinese.

[EUROPE]

- France (3)

Germany (2)

Great Britain (2)

Greece (1)

Holland (2)

Italy (9)

Spain

[EASTERN EUROPE, WESTERN FSU]

none

[NORTH AMERICA]

- USA (11)

[SOUTH AMERICA]

none

[ASIA]

Hong Kong (1)

India (4)

Japan (1)

- Nepal (4)

Singapore (1)

Taiwan (1)

[AFRICA]

none

[AUSTRALASIA]

- Australia (11)

New Zealand (2)

Tahiti (1)

Table 2. THE FOUNDATION FOR THE PRESERVATION OF THE MAHAYANA TRADITION, 1993

Table 2 is a similar listing for the FPMT, dating from late 1993. Here the number of centres in each country is indicated, and a star * marks a regional office. [6] The FPMT have a stronger presence in Nepal and India than the Dzogchen Community, which is not surprising, since they originated in Nepal, but they have not expanded significantly into Eastern Europe or the former Soviet Union and have no links to Tibet proper. While the FPMT network is smaller in extent than the Dzogchen Community's, it is probably larger in actual numbers, since their membership in countries such as Spain, Italy, Australia and the USA is extensive and long-standing, and the FPMT has several centres in each of these countries.

The FPMT's lack of links to Tibet derives historically from the relatively marginal position of Lama Zopa and Lama Yeshe in the Tibetan Buddhist context. The network has however been involved in fund-raising for refugee Tibetan monasteries, and has also developed other modes of charitable work. The eleven Australian centres, for example, include three hospices, and the network also operates a leprosy centre, a home for the destitute and a clinic.

One might ask to what extent these networks are integrated into higher-level structures. There are some suggestions of such linkages. I have already mentioned the Dalai Lama's visit to Kollegal, for example. The Dalai Lama's overseas visits have provided a general context for meetings between groups, as have various national and regional Buddhist organizations in various Western countries (e.g. the United Kingdom, Australia).

Other links are more specific. Thus Chögyam Trungpa's organization kept up close links with the Gyalwa Karmapa (1924-81), the senior lama of the Karma bKa'-brgyud-pa tradition to which Trungpa belonged, and to Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche (1910-91), a senior rNying-ma-pa lama who had been one of Trungpa's own teachers and was recognized by Dharamsala as the head of the rNying-ma-pa order. [7] Trungpa's organization was instrumental in arranging visits to the West by these lamas, and Dilgo Khyentse presided over Trungpa's own funeral rites in 1987. More recently, Penor Rinpoche, who has succeeded Dilgo Khyentse as head of the rNying-ma-pa, undertook a tour of the US and Europe in which he visited Trungpa's former centre in Canada, a retreat organized by Sogyal Rinpoche in France, and Namkhai Norbu's centre in Italy, as well as giving a variety of teachings in other places, including the U.K. While in Canada, he performed a formal enthronement ceremony for Trungpa's son, the Sawang Ösel Rangdröl Mukpo (subsequently known as Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche), who has now taken over as head of his organization. Similarly, the FPMT and other dGe-lugs-pa affiliated groups have been involved in sponsoring visits by senior dGe-lugs-pa lamas in India such as Kirti Tsenshab Rinpoche.

Such contacts are significant but they do not, I think, amount to very much in the way of hierarchical authority. At most, events such as Penor Rinpoche's enthronement of Trungpa's son represent claims of mutual relationship, no doubt carefully negotiated by both sides, in the tradition of the complex relationships between Tibetan lamas and secular rulers, including the Mongol and Manchu emperors of China. [8] Equally, while the Dalai Lama is accorded great respect by all Dharma groups (with the partial exception of the New Kadampa Order), they do not expect to receive instructions from him, at most advice.

6. The Transformation of Tibetan Buddhism

Thus we see that Westerners joining a Tibetan Buddhist organization characteristically find themselves part of an international network which encompasses both Western and Asian elements, and which is under the direction of a Tibetan lama. I have implied in the course of my paper that this is a situation which has at least some resemblances to the practice of Tibetan Buddhism in its pre-modern context. Pre-modern lamas had networks and centres extending over long distances, and travelled between their centres in ways not entirely different from the constant touring required of many contemporary lamas between their geographically scattered groups of followers.

Thus the basic concept of a diverse network encompassing a variety of different constituents in terms of life-style and ethnicity is not new. To put it differently, lamas in pre-modern Tibet might also have expected to acquire a varied following in a number of locations. This was perhaps a natural consequence of the mobility of Tibetans and the entrepreneurial nature of Tibetan Buddhism.

There are, of course, ways in which the new networks differ from those characteristic of the pre-modern situation. In particular, modern communications and technology have enabled both a far wider spread to these networks than existed in the pre-modern period, and a greater degree of connectivity than generally existed in Tibet, where travel was slow, and hampered by weather and, in many areas, the risk of bandit attacks. The journey from Amdo to Lhasa typically took several weeks' travel through difficult and dangerous terrain and was not undertaken casually. Today, air travel enables the lama to give periodic teachings in centres around the globe, and postal services, not to say telephones, fax and the Internet enable effective communication around the global network.

This provides the possibility for a greater degree of central control than before, a possibility which is also encouraged by Western models of centralization. While such centralization, however, makes it possible for a single lama to maintain a network on a global scale, it has not as yet led to the integration of these various networks into some kind of super-ordinate structure. In this sense, the decentralized and entrepreneurial logic of Tibetan Buddhism remains active in its new context. Networks are, in a sense, competing with each other for customers and finance, although many Western Buddhists may maintain some level of involvement with several different networks.

This leads to a certain degree of differentiation between the varieties of Dharma offered by the various networks. This is a development which in any case is natural enough given the variety of backgrounds and personal careers of the lamas who direct them, the constant interaction between Tibetan and Western modes of thought, and the persistence of indigenous modes of visionary creativity and transformation such as pure vision (dag snang) and gter ma-discovery through which lamas introduce new practices and concepts (Samuel 1993: 294-302).

In these and other respects one can, I believe, see continuity between patterns of Buddhist social organization in pre-modern Tibetan societies and those found among modern Tibetan-derived Buddhist groups. As in the pre-modern situation, there is considerable scope here for each lama to develop his or her own approach, aided by the large repertoire of practices, teachings and texts within most Tibetan traditions. In the process, the West is being offered a range of different versions of Tibetan Buddhism.

As in the case of pre-modern Tibet, however, it is important to realize that with these networks we are not simply dealing with a Tibetan lama presenting Tibetan Buddhism to a variety of Tibetan and non-Tibetan followers, but with a total entity composed of sub-units of markedly different type and structure. This leads me to a theoretical problem which in a sense underlies the entire paper, although I have to admit that I have not got very far as yet in dealing with it. How does one analyze entities of this kind? More specifically, what can one say in anthropological terms about an entity that spans multiple cultural contexts and includes a variety of sources of authority?

One can, of course, analyze such entities in purely economic terms, and I have no doubt that such an analysis would throw some light on their functioning, but it seems unlikely that it will yield an exhaustive analysis. I am more interested in what one might (guardedly) call the cultural dimension; the effect of differing attitudes and motivations across the networks. Here I will just make a few preliminary points:

• the problem of stability

International Buddhist networks are not necessarily very stable structures, and are liable to fragmentation and breakup. There have been at least two breakaways, for example, from the FPMT organization, both led by lamas initially appointed as FPMT teachers, Geshe Thubten Loden in Melbourne, Australia, and Geshe Kelsang Gyatso at the Manjushri Institute (Conishead Priory) in Cumbria, England. In Geshe Loden's case, the lama set up a separate centre outside the FPMT network and then withdrew more or less amicably from the network to direct this centre. In Geshe Kelsang Gyatso's case, the break was more acrimonious, and the Geshe took over into his new organization, the New Kadampa, much of the property of the FPMT in the UK, including Manjushri Instiute, an extensive property in Cumbria which had been initially acquired for the FPMT in 1976.

The root causes here seem to have been a conflict of authority, with Geshe Kelsang Gyatso disagreeing with the FPMT's central administration under the direction of Lama Thubten Yeshe and Lama Zopa in Nepal, and an associated conflict in style. Geshe Kelsang Gyatso, as subsequent developments have made clear, belongs to a conservative faction of the dGe-lugs-pa with close links to the eminent early 20th century dGe-lugs-pa scholar P'awongkha Rinpoche and his student, the Dalai Lama's former Junior Tutor, Trijang Rinpoche. Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa, despite their initial associations with the P'awongkha tradition, represent a more open and tolerant approach to the dGe-lugs-pa tradition. Geshe Kelsang Gyatso's organization, the New Kadampa, has developed into an exclusive tradition focussing only on the Geshe's own publications and discouraging its students from any contact with other lamas or teachings. [9] The FPMT subsequently re-established their own organization within the UK independently from the NKT, although their British organization remains much smaller than that of the NKT.

The FPMT chose from fairly early on in its development to find resident Tibetan teachers for its major centres around the world, and this choice, as the Geshe Loden and Geshe Kelsang Gyatso episodes illustrate, carried with it a risk that local lamas would split off and form organizations of their own. Other networks, such as Rigpa and the Dzogchen Community, have remained dependent on a single lama at the centre and his or her ability to keep up contacts with the local groups. This can involve a punishing schedule of retreats in centre after centre about the globe, and there is perhaps a natural limit to the kind of organization that can be held together in this way. In fact, both Rigpa and the Dzogchen Community in recent years have begun to arrange retreats with lamas from related traditions to those of their presiding lamas at their organization's regional centres.

• the interlacing of networks

I referred before to the visits by high-status Tibetan lamas such as the Dalai Lama, Gyalwa Karmapa, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche and Penor Rinpoche which serve to link together the otherwise autonomous networks of individual lamas. In addition, there are "horizontal" linkages, in which lamas may recommend that their students study with lamas of related traditions, or invite such lamas to teach at their own centres. This provides a way, as noted earlier, of reducing the strain of continuous visits to all of the various nodal points in a lama's network. Thus Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche, has at various times advised students of his to attend teachings with Sogyal Rinpoche and Chagdud Rinpoche, who while having quite different personal styles and approaches to the material from each other and Namkhai Norbu, derive from a similar background and teach material from the same traditions. He has also invited rDzogs-chen teachers from the related Bon-po tradition to teach at his centres in Italy and elsewhere. This is perhaps a recognition of the inevitable; Western Dharma students are involved in a process of guru-shopping, and are likely to try other teachers in any case, especially if there are long intervals between the local appearances of the person they currently regard as their principal teacher.

These visits and cross-cutting links create a kind of interweaving between the networks of different lamas. Some networks are closer to each other, some more distant; thus Ris-med lamas from the bKa'-brgyud-pa, rNying-ma-pa and to some extent Sa-skya-pa traditions group together, as opposed to the dGe-lugs-pa networks, but all are closer to each other than to Theravadin or Zen Buddhist groups, and people from all the Tibetan groups might attend a mass empowerment by the Dalai Lama, for example.

• processes of adaptation

The global network has considerable resources, but is also under complex constraints. I give two brief examples as illustration:

• the need (from the Western side) for female lamas and of feminist-oriented teachings in response to the developing feminist critiques of Buddhism among Western Buddhists. Here the refugee community provides a resource (female lamas) which can solve the problems of the Western Dharma centres, but the solution involves women who have traditionally taken a less public role in Buddhist teaching moving into new positions, and is likely in time to have an effect on the gender definition of the lama role among the Tibetans themselves. Given the level of Western Buddhist concern about such issues, movement here is relatively slow, and as far as I know limited to the non-dGe-lugs-pa traditions. [10] A change which is highly motivated in one part of the network is perhaps being resisted in other parts.

• the need (from the Tibetan and refugee side, and particularly from the Dharamsala administration) for political support for the cause of Tibetan independence. Here Western Dharma groups can to some degree be mobilized for fund-raising and political action, but many Western Buddhists have only limited interest in such matters. In addition, Tibetan lamas may have ambivalences about too close an identification with Dharamsala if this prejudices their ability to work with their communities back in Tibet.

In each case, one could say that the network gradually moves towards a compromise state in which needs all around the component parts are relatively satisfied.

In a later paper, I hope to analyze in more detail the ways in which these networks operate and the consequences they have had for the nature of Tibetan Buddhism in the West. The problem is, I think, one of considerable theortical interest, and perhaps of some practical concern too. The global networks of Tibetan lamas are, after all, only an example of a whole new class of global entities that are increasingly going to constitute the world within which we and our children live. The more we can understand about how they function, the better.

References Cited

BLOFELD, John (1972) The Wheel of Life: The Autobiography of a Western Buddhist. London: Rider.

ELLINGSON, Ter (1990) "Tibetan Monastic Constitutions: The bca' yig." In Laurence Epstein and Richard F. Sherburne (ed) Reflections on Tibetan Culture: Essays in Memory of Turrell V. Wylie. Lewiston, Queenston, Lampeter: Edwin Mellon Press, pp.205-30.

HEISSIG, Walther (1980) The Religions of Mongolia. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

HELFFER, Mireille (1993) "A Recent Phenomenon: The Emergence of Buddhist Monasteries around the Stupa of Bodnath." In Gérard Toffin (ed) The Anthropology of Nepal: From Tradition to Modernity. Proceedings of the Franco-Nepalese Seminar held in the French Cultural Centre, Kathmandu, 18-20 1992. Kathmandu, Nepal: French Cultural Centre, French Embassy, pp.114-131.

KAY, David (1995) Draft material on the New Kadampa Tradition. Typescript.

KAY, David (1997) "The New Kadampa Tradition and the Continuity of Tibetan Buddhism in Transition." J. Contemporary Religion 12: 277-293.

MACKENZIE, Vicki (1995) Reborn in the West. Bloomsbury.

MELLOR, Philip A. (1990). "Protestant Buddhism? The cultural translation of Buddhism in England." Religion 21: 73-92.

NATTIER, Jan (1995) "Visible and Invisible: The Politics of Representation in Buddhist America." Tricycle 5,1 (Fall 1995), pp.42-9.

SAMUEL, Geoffrey (1993) Civilized Shamans: Buddhism in Tibetan Societies. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

SCOTT, David (1995) "Modern British Buddhism: Patterns and Directions." Paper for The Buddhist Forum, Department of the Study of Religions, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

SHARF, Robert H. (1995) "Buddhist Modernism and the Rhetoric of Meditative Experience," Numen 42: 228-83.

STUTCHBURY, Elisabeth (1994) "The Making of Gonpa: Norbu Rinpoche from Kardang and Kunga Rinpoche from Lama Gonpa." In Geoffrey Samuel, Hamish Gregor and Elisabeth Stutchbury (ed) Tantra and Popular Religion in Tibet. New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture and Aditya Prakashan, pp.155-89.

Notes

[1] Whether this is an accurate characterization of Buddhism in its various Asian contexts is quite another question.

[2] As distinct from communities such as the Ri-pa bLa-brang at Chandragiri that maintained "mixed" traditions already established in Tibet. These were typically, as in this case, communities that maintained both bKa'-rgyud-pa and rNying-ma-pa lineages.

[3] As contrasted with the first Tibetan monastic centre for Westerners, Samyê-Ling in Scotland, founded by the bKa'-brgyud-pa lama Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche in 1968 with the aid of his Western supporters. The property had been acquired and established as a Buddhist centre by a Western Buddhist teacher, Ananda Bodhi, in 1967, who gave it to Trungpa when he moved to Canada. Chögyam Trungpa himself later moved to North America, and Samyê-Ling has subsequently been directed by Akong Rinpoche.

[4] Quotation from FPMT site on the World Wide Web, October 1995.

[5] See the FPMT journal Mandala , Issue No.13 (October 1993), pp.1, 16-17.

[6] The reason for the limited representation of the FPMT in the UK is that most of the British groups broke away some years ago under the direction of Geshe Kelsang Gyatso and formed a separate network, the New Kadampa, on which see below.

[7] It should be noted that there was no such position of head of the rNying-ma-pa order before 1959. The most senior lamas were heads of the major rNying-ma-pa monasteries in Central and East Tibet.

[8] See the descriptions in the "Shambhala News" sections of the Shambhala Sun for January 1995, May 1995, September 1995. The changing definition of the rebirth status of Trungpa's son is of particular interest. He was originally described as a rebirth of the lama-king of the Tibetan epic, Ge-sar of gLing, but was actually recognized by Penor Rinpoche as a rebirth of the late 19th century scholar-lama 'Ju Mi-pham Rin-po-che. Mi-pham, who was known for his visions of Ge-sar, could be viewed as a safer and less controversial choice, without the overtones of secular political authority present in the original identification.

[9] I am relying here in part on David Kay's research on the New Kadampa, which he was kind enough to make available to me (Kay 1995). See also Scott 1995. David Kay has suggested to me that Geshe Kelsang Gyatso's secession from the FPMT was provoked by a tightening up of central control consequent upon Geshe Loden's departure (personal communication, February 1996). [Some of David Kay's material on the New Kadampa has since been published as Kay 1997. - G.B.S.

[10] See for example the recent prominence in Western Dharma circles of such female lamas as the Sakya Trizin's sister Sakya Jetsun Chimey Luding (The Mirror, no.28, Sept-Oct 1994), the late Khyentse Rinpoche's consort Khyentse Sangyum (who has participated in recent retreats directed by Sogyal Rinpoche), and the young rNying-ma-pa female reincarnate lama Khandro Rinpoche (Shambhala News, March 1996); also the recognition of a Western woman as a rNying-ma-pa reincarnation (Mackenzie 1995).