Life of Ja Lama

At the time Dambijantsan was born, at the beginning of the 1860s, Tibetan Buddhism, despite the continued pressure to convert the Kalmyks to Russian Orthodoxy, was still prevalent in Kalmykia, the land of the Kalmyks. In all likelihood Dambijantsan was born into a family which adhered to Buddhism to one degree or another. The first news we hear of him is that at the age of seven he was supposedly enrolled as a novice in a Buddhist monastery in Dolonnuur, in what is now the Chinese province of Inner Mongolia. Maisky heard this story while in western Mongolia in 1919, when Dambijantsan was still alive. Dolonnuur was firmly in the orbit of the Eastern Mongols, the Chahar of Inner Mongolia and Khalkh of what was then considered Outer Mongolia, and at first glance it appears strange that a young Dörböt from the Volga River in Russia would have gravitated there. Kalmyks wishing to enter a monastery outside of Kalmykia, we would think, would have been more drawn to western China, including the modern-day provinces of Xinjiang, Qinghai, and Gansu, the traditional strongholds of the Torgut, Dörbot, and other Oirats, both those who not migrated westward in the early seventeenth century and those who had returned in the great exodus of 1771. Fred Adelman, in his introduction to Pozdneev’s Mongolia and the Mongols makes precisely this objection, and John Gaunt in his doctoral thesis on Dambijantsan repeats it: “it would be unlikely to find a Volga Kalmuk at Doloon Nuur, as they were not oriented toward Inner Mongolia’s monastic net”.

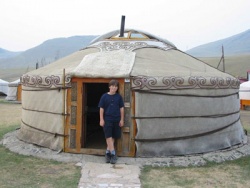

In the early Spring of 1912 Dambijantsan and his disciple Jimbe left his Headquarters on the Dund Tsenkher Gol and traveled north to the Dörvöd Dalai Khan and the Dörvöd Zorigt Khan aimags in the the border region to the west of the four Khalkh aimags. As their names implies, these aimags, located in what is now Uvs Aimag and northern Khovd Aimag, were in large part inhabited by Dörböd, the tribe Dambijantsan supposed belonged to back in Kalmykia. While in Dörvöd Dalai Khan Aimag Dambijantsan first meet with A. V. Burdukov, the Russian trader who would become his close friend and who would write at length about him in his book Old and New Mongolia. Burdukov at time had a homestead and trading post at Khangeltsyk, near the town Tsagaan Khairkhan in current-day Uvs Aimag, northeast of Khyargas Nuur. Burdukov visited Dambijantsan in a ger where he was staying:

At first we thought that they (Dambijantsan and Jimbe] were just two badarchin, but people said no, they are very significant people. He was about 40–45 years old, stout, strongly built, with a round, purposeful face. He had a high forehead and bright, shining eyes. Although he was dressed as a Tibetan lama in a maroon gown with broad cuffless sleeves, he wore a well-made pair of Russian boots, and peeping out from under the gown was the collar of an old Russian military uniform. His accent was neither Khalkh nor Oirat but a mixture. Mausers were hung on the wall of the yurt. He knew much about events in Mongolia, Russia, and China. He inspired belief in him by others to an extraordinary degree. People came into his yurt and asked his blessing, which he always gave. He looked like someone born on the steppe and at the same time as an experienced agitator.

In the course of his conversations with Burdukov Dambijantsan spoke about India and Tibet, where he claimed to have traveled extensively. “There could be little doubt as to the man’s wide experiences and travel,” Burdukov noted, “his information about the countries he mentioned was remarkably precise and detailed . . . Ja Lama had a command not only of the Mongolian language, but of Chinese, Tibetan, and Sanskrit as well, and he also knew a bit of Russian.” (Oddly, the Diluv Khutagt claimed that Dambijantsan, despite the years he had supposedly lived in Tibet, could not speak Tibetan at all.) Maisky, traveling through the region a few years later when stories about Dambijantsan’s first appearance there were still in circulation, also commented on Dambijantsan’s extensive travels in India, Tibet and elsewhere: “A man who had gone through this kind of schooling [his various travels] and acquired some smattering of European culture would under any circumstances greatly impress the simple-minded Mongols . . .”

But not only was he well-traveled and supposedly well-educated, he was also the successor to Amarsanaa, a claim which he never tired of repeating. Maisky’s comments on the effects this assertion had on the locals:

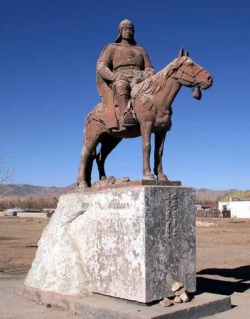

One can . . . easily imagine the sensation Ja Lama created among the Durbets [Dörböds] when he let them in on the “secret” that he was none other than a descendent and reincarnation of the renowned Amursana and that the last hero of Mongolian independence had become incarnated in him so that he, Ja Lama, might lift the Chinese yoke from his native land. There was great excitement among the tribes of the Khovd region. The name of Ja Lama was on all tongues. Everyone saw him as the savior of the fatherland. Princes, lamas and plain folk came flocking to the newly-risen leader and donated livestock, silver, cloth, etc. In a short time, the bold monk became in fact the ruler of the Kobdo Mongols. He now began his activities in earnest.

Dambijantsan’s prestige in Dörvöd Dalai Khan Aimag was enhanced by all kinds of magical acts which were attributed to him. He seemed to know all the life-stories and even the most intimate secrets of all the important people in the area. People put this down to his supernatural powers of cognition and mind reading, but as Burdukov pointed out he might well have gotten this information from the gossip of the many people who were constantly coming to him for blessings. Burdukov also mentioned that at one point he took some photographs of Dambijantan. He later inadvertently re-exposed the negative containing Dambijantsan’s image when he was taking a photo of local Mongolian noblemen. When the negative was printed the faces of the Mongol princes showed up on Dambijantsan’s sleeve. Despite Burdukov’s explanations of what had happened, the Mongols who saw this photograph insisted that this was further proof of Dambijantsan’s magical powers. HIs every act took on a special significance. He frequently gave his disciple Jimbe severe beatings, but witnesses took this to mean that Jimbe was a great sinner and that Dambijantsan was performing a virtuous act by punishing him. In the eyes of many Dambijantsan could do no wrong. Non-Human Origins of Dambijantsan

Given the mystery surrounding his birthplace, his age, and many of the subsequent events of his life it is perhaps to be expected that in Mongolia a supernatural version of Dambijantsan Mythologem would eventually arise. This tale was told to me by a well-known and highly respected lama in Ulaan Baatar. When this lama’s teacher was a young man he had as his own teacher a lama who as a boy had lived with his parents at Dambijantsan’s Final Stronghold in the Black Gobi Desert in what is now Gansu Province, China. This lama related that Dambijantsan, despite his ferocious demeanor, liked to play with children. On sunny afternoons he would sit down outside, take off his shirt, and let a whole passel of small children climb over his body and hang on his neck. One day while horsing around in this manner our informant noticed that Dambijantsan had no belly button. He did not realize the significance at this at the time, but later he heard stories about beings who did not have belly buttons because they had not been born to a human mother and were not human beings themselves. Later in life this man came to believe that Dambijantsan was not actually a human being.

My own informant explained to me that this belief in entities who only appear to be human beings is fairly widespread in Mongolia. The telltale sign is the lack of a belly-button and the inevitable uncertainly surrounding the being’s family and origins. In the past such appearances were uncommon, but they did happen, he claimed. According to persistent rumors, Dondovdulam, the first wife of the Eighth Bogd Gegeen)], was one of these non-human entities (this is of course hotly disputed by those who claim she came from an ordinary family at Baldan Bereeven Khiid).

So what are these entities, and from where do they originate? As best my informant could explain, they are thought forms which have been manifested as material objects in the three-dimensional world by some power or force, the exact nature of which is unknown to us. They are created to accomplish some specific task, the ultimate goal of which is not always clear to human beings. As manifested entities, these beings lack the life story of a human being.

Thus the tales about Dambijantsan’s birth in Kalmykia, Inner Mongolia, Outer Mongolia, China, or elsewhere were blinds, perhaps created by in part Dambijantsan himself, to hide his true, non-human origins. The uncertainly over his birth date; the observation by some that he did not appear to age over time; the magical acts for which he later became famous, his alleged immunity to bullets and the belief, widespread during his lifetime, that he could never be killed by ordinary means were all a result of his non-human origins. Even the fact that he was eventually killed is tempered by the belief on the part of some that his material body was allowed to be destroyed because it was no longer of use to its creators but that his thought form continues to exist into the present. It might be added in conclusion that these entities no longer appear in material form in Mongolian today, mainly because the powers which produce them have disappeared or are at least in abeyance, but that in the future they may well occur again.

I do not present this theory here necessarily because I believe it; I do so only to demonstrate the incredible breadth of the tales which have accrued around the life of Dambijantan and which continue to be believed by at least some people down to the present day. But when these tales, bizarre as they may seem, are told by the light of a campfire at One of Dambijantsan’s Former Haunts, deep in the Gobi Desert eighty miles from any other human beings, they are not so easily dismissed.

By the beginning of 1914 Dambijantsan’s reign of terror had antagonized many of this former supporters in western Mongolia. According to the Diluv Khutagt, “The people of the Banners of that region were unable to sleep in peace, and secretly went to the Russians with a petition of complaint” accusing Dambijantsan of “autocratic and despotic behaviour.” The complaint was presented to the Russian consul in late January of 1914 by several western Mongolian princes, including the Baid Noyon, the chieftain of the Baid people who had earlier befriended Dambijantsan. They believed he was a Russian citizen and that therefore it was the responsibility of the Russian authorities to somehow rein him in

While camped on the Dund Tsenger Gol the Ja Lama a.k.a. Dambijantsan may also have spent some time at Khoid Tsenkher Agui (agui = cave), located in the valley of the Khoid Tsengker Gol, about fifteen miles west of the Dund Tsenger Gol camp.

This is one of the largest caves in Mongolia, with a main chamber at least eighty-five feet high. A rock fall in 1995 blocked off one long extension in the cave, but several smaller galleries leading off from the main chamber still remain.

I have visited this cave several times. On my last visit in 2007 my jeep driver related that two years before he had served as a driver for a prominent Tibetan lama from Sichuan Province in China. Unfortunately he could not remember the lama’s name. The lama was interested in various historical sites, including Tögrögiin Khüree in the current town of Mankhan. They also visited Khoid Tsenkher Agui. While at the cave the lama mentioned that the famous magician Dambijantsan had once meditated in the cave and had acquired some kind of special powers there. The jeep driver said that he himself had not mentioned Dambijantsan and it did not occur to him at the time to ask the lama how he know about him, nor did he think to ask about the nature of the powers Dambijantsan had supposedly acquired there. Only later did it strike him as odd that a Tibetan lama from China would know about Dambijantsan.

In this connection it is worth mentioning that Professor Baasankhüü, who was with me on my 2007 trip to the cave, had visited the cave in 2006 with controversial Russian researcher of paranormal phenomena Ernest Muldashev. After conducting various investigation in the cave Muldashev announced that it was infested with spirit entities—“light bodies”, or gerlen bie in Mongolian—identical to those he had previously discovered in caves in Tibet. These Love craftian Entities, Muldashev claims, existed before the appearance of humans on this earth and will be instrumental in deciding what form Consciousness will take after we humans have at long last worn out our welcome and finally disappear for good from our now-beloved orb. Muldashev’s theories, outlined in Numerous Books (he too has weighed in on the Shambhala Mythologem)—some of them already translated into Mongolian—are Understandably Controversial and have come under attack from various quarters. Indeed, some consider him a Charlatan of the First Water. The professor says he is keeping an open mind in the matter. Whether Dambijantsan somehow communicated with the spirit entities in the cave—assuming they existed—and perhaps acquired some supernatural powers from them must remain a matter of speculation.

I have already written about the arrival of Dambijantsan in Western Mongolia in 1911 and how he established a Winter Camp on the Dund Tsenkher Gol near Mankhan, in Khovd Aimag.

In 1999 and again in 2007 I visited Dambijantsan’s camp on the Dund Tsenkher Gol, both times accompanied by Professor Baasankhüü of the Khovd branch of the National University of Mongolia. In 1972 the Professor had come to the Dund Tsenkher Gol with an eighty-two year old man named Jigmid who had been a follower of Dambijantsan and who had camped with him here. From Jigmid the Professor was able to get a fairly detailed account of events here on the Dund Tsenkher. Jigmid related to the professor that Dambijantsan liked to stay apart from his followers and soldiers. His own ger was on a high bank to the left of the Dund Tsenkher Gol, facing downstream, close to the mouth of a canyon from which the swift-flowing river emerges.

The campgrounds of his followers was about a mile farther on downstream, on the same side of the river. Jigmid said that Dambijantsan always liked to have a mountain or steep hillside behind his ger or tent, which would make it hard for enemies to approach from the rear, and an clear, unobstructed view in front, making it difficult for anyone to approach undetected from that direction. These conditions were met here; the ramparts of the Mongol-Altai rise directly behind his ger site and in front a bare plain stretches for ten miles or more.

For further protection, Dambijantsan had a stone wall constructed around his ger, the remnants of which can still be seen today.Oddly enough, right next to his ger site are several well-preserved Bronze Age tombs. I asked the Professor if it was customary to set up a ger so near to ancient tombs like this, and he said it wasn’t, but that Dambijantsan apparently did not concern himself about such matters.Jigmid had also said that on the steep hillside behind the ger site Dambijantsan had constructed stone watchtowers. Several heaps of rock of the hillsides may be the remains of these watchtowers.

The campgrounds of his followers was on level ground, directly on front of his ger and about a mile away. Dambijantsan was a stickler for neatness and order and the camp was always spotlessly clean. He did not even like loose rocks lying around where people might stumble over them, and when his followers weren’t doing anything else he had them gather up these rocks and put them in piles. These piles of rock can still be seen there today.A German traveler in the region at the time, Herman Consten, also visited to the site and gave a description in his book Weideplätze der Mongolen: “The Mongolian camp makes a surprisingly good impression . . . the tents and gers are pitched in a double circular line around the centre of the camp. . . The path which leads to the ger of the Ja Lama is astonishingly clean like the camp.” He added that the “the ger of Ja Lama, (the Two Camel Lama) stands out from from the other gers by the white of its costly felt and its large size.”

Dambijantsan may have intended to establish a permanent base here, or even found a town. In the spring of 1912 he had his followers plant crops in newly-established fields watered by irrigation ditches from the nearby Tsenkher Gol. The traces of these fields and irrigation ditches can still be seen there today. As it turned out, his early attempts to establish some kind of community here was only a dry run for his later settlements and strongholds.

An ever larger contingent of disciples and followers who had fallen under Dambijantsan’s charismatic spell soon gravitated at this camp. Not all were there voluntarily. In his ger Dambijantsan kept a thirteen year old boy as a servant. Treated as a virtual slave and repeatedly beaten for minor offenses, the boy wanted desperately to escape, but he lived in mortal fear of Dambijantsan. Soon he devised a plan to kill his master. Every morning Dambijantsan would go out and inspect his soldiers and then come back and sit on a stool behind the stove and drink tea. The boy decided that when Dambijantsan sat down he would hand him a cup of tea with one hand and with the other grab the axe that was kept in the woodbox beside the stove and break open his skull with it. Dambijantsan came in and sat down, then grabbed the axe himself and hit the boy along the side of the head with the flat side, knocking him down. “Did you really think you could kill me with an axe?” he asked the boy. The boy was sure he was about to die, but instead Dambijantsan handed him a Buddhist scripture wrapped in a yellow cloth and said, “Our paths in life are quite different. You must go your way and I will go mine. Take this book and go to Khovd and became a monk. But never let me see you again or I will kill you.” The boy did as he was told and joined a monastery. He eventually became famous for blessing new Russian jeeps. Before he died in the late 1980s he told people in Khovd that Dambijantsan had known his intentions because he had been able to read his mind. This one just one of the many stories of Dambijantsan’s mind-reading skills which continue to be told down to the present day.

Around this time Dambijantsan became famous for a whole host of magical abilities. According to the Diluv Khutagt:

Ja Lama claimed to be able to cure sickness with gun magic. This is a very old form of magic. The sickness is reported to the magician. The magician thinks about the disease. Then he fires a gun in the direction of the sick man. The sick man may be hundreds of miles away, but he hears the report, and at that moment he is cured.

Diluv Khutagt again:

Ja Lama also did other kinds of gun magic. Each of Ja Lama’s bullets had a Tibetan letter on it—I don’t know which letter. It was reported that a camp was raided by a wolf. Half of the sheep stampeded into the night. The shepherds ran and told Ja Lama. “I’ll fix that,” he said, and he lifted his gun and fired from the door of his tent. “Go and look in that direction tomorrow morning,” he said. The next morning they went and looked and saw the sheep all grazing peacefully, and the wolf lying dead beside them. They cut open the wolf ’s body and found one of Ja Lama’s bullets in it. After that everyone feared and respected Ja Lama.

To this day variations of this story are told by old people in Khovd Aimag who claim they themselves heard about it from eyewitnesses who had actually met Dambijantan. Usually, however, they have Dambijantan shooting his gun several times through the toono, or round hole, in the roof of a ger and not out the door, and no mention is made of a Tibetan letter on the bullets. Old people near Bayan Tooroi, in Gov-Altai Aimag, told me the same story, claiming that Dambijantsan had performed this same trick while passing through the area in 1918.On May 12, 1917, Dambijantsan, still an exile under police supervision, arrived in Astrakhan, the ancient city near the mouth of the Volga River, and took up residence on what is now Pestelya Street.

On June 20, 1917 he received a letter from A. V. Burdukov, the Russian trader in Mongolia who had befriend him during his earlier stay in Mongolia. On the same day he sat down and wrote a reply to Burdukov. “I am extremely delighted by the warm greetings from you and your wife and by your kind and sincere wishes for me,” gushed the one-time torturer, always a gentleman in his letters. He mentions that he would be released from police supervision sometime in 1917 but added that he had no plans to return to Mongolia, contrary to what he had written before. Indeed, he now complains that the Mongol people had never properly appreciated the efforts he made on their behalf: “ . . . trying to free Mongolia from the Chinese yoke, I have gained nothing for myself except a lot of psychological and physical problems . . . as a result of my kind efforts toward the well-being of the Mongolia nation I have only suffered . . .”

He is still involved with some kind of unspecified business affairs with Burdukov and asks about the money that was supposed to be forwarded to him via Russian consulate in Khovd. Meanwhile inflation is running wild, the prices of all commodities, including mutton, bread, butter, are soaring. “Nothing is reasonable,” he grouses, and boots are altogether unavailable. He also asks for photos of Mongolian noblemen he knew and a copy of a magazine article about his exploits during the Siege of Khovd in 1912. He may have claimed that he had no intention of returning to Mongolia but his thoughts were clearly turning there. On June 30 he wrote again in reply to a letter of Burdukov’s:

I am safe and sound, thanks the Lord. I would like to thank you for your kindness and sincerity to me. You were the first among my friends whom I met in Mongolia and now the one who writes a letter with kind and faithful regards to me. I am extremely happy to receive your letter, I will never forget your kindness and friendly treatment to me. Could you please send my best regard to your wife?

He then reiterates his complaints about the ingrate Mongolians:

I am really disappointed that my efforts done for the welfare of Mongolia were not valued. I fought with China for two years in order to release my fatherland from the Chinese yoke. I was wounded twice during the war, I didn’t try to spare myself; I risked with my life for Mongolia. This year I am going be released from police supervision, but anyway I am not going to Mongolia this year. I didn’t do or even think to do anything bad for my Fatherland, but my Fatherland didn’t try to save and protect me when I was in a disastrous circumstances . . .

Oddly, he mentions a college he claims to have founded in the “Altai Region.” He only wanted the people there to be “literate and intelligent” but for this act of magnanimity the Mongols were also ungrateful. There is no other mention anywhere of this college by Dambijantsan or anyone else and it might well have been the product of his imagination.

By then situation had deteriorated even further. Bread was valuable only with a ration card. One person was permitted to buy only two pounds of flour and five pounds of rice a month. New boots were a staggering 120 rubles.

The good news was that the Astrakhan officials had been informed by telegram that the money Burdukov had given to the Russian consul in Khovd was on the way by post. He expected to receive it in a few days. He also notes in passing that on June 28, two days before, he had met with the academician B. Ya. Vladimirtsov, who had early recorded the epic poetry about Dambijantsan’s role in the siege of Khovd. For a more substantial account of this encounter we have to turn to Vladimirtsov’s own letter to Burdukov, dated Sept. 12, 1917. Dambijantsan, Vladimirtsov discovered, had changed considerable:

When he first entered the room I did not recognize him. Nothing was left of the previous Ja Lama. Try to picture a thin, gaunt man, dressed in a suit and lacquered books. He made a low bow and with great effort I finally recognized him. Once he was the formidable and awe-inspiring Dambijantsan! Such is Fate!

Dambijantsan told Vladimirtsov that he living fairly well in Astrakhan and that he was pretty much free to come and go as he pleased, although technically he had not been released from police supervision. No one was really interested in him. No one in Astrakhan knew that he had once been a monk (and apparently no one knew about his dubious past in Mongolia). He repeated his gripe that the Mongols did not appreciate his efforts to regain their freedom. He claimed that he suffered greatly in his attempts to help his own people, the Dörböts, but they too did not believe in him. Now, he claimed, he wanted to live among Russians and not Kalmyks or Buryats. He was, so Vladimirtsov thought, renouncing his whole past. “Who is this character, who is this person? wondered Vladimirtsov, “I couldn’t manage to understand this man. In most ways, he now makes a pitiful impression.”

Dambijantan appeared to be at loose ends. “To my mind, if he wanted, he could go anywhere. And despite what Dambijantsan said, Vladimirtsov could not shake the idea that he had “some special plans” up his sleeve.

On August 1 Dambijantsan replied to Burdukov’s letter of June 3, which he had received that very day. Apparently Burdukov had send him some khadags and fabric by separate mail but he had not received these yet. He says that very soon now he will be released from police supervision but that he still has no plans to return to Mongolia. “I want to live in Russia for now, maybe forever,” he writes. But his interest in Mongoiia has not died out completely. He asks Burdukov to send photos of prominent princes and lamas, including the Sartuul Tsetsen Van, Jalchiggombodorj, who ruled over the Sarts who lived in what is now northwest Zavkhan Aimag and eastern Uvs Aimag and who earlier had been a partisan of Dambijantsan’s. Was Dambijantsan just getting nostalgic, or was he actually trying to keep up his links with his former followers in Mongolia. In most of his letters he states that he has not intention of returning to Mongolia but could this have been for the benefit of the police, who might well have been reading his correspondence?

Every day he went to the post office checking for the money which the Russian consul in Khovd had supposedly sent him. Thus he was in the uncomfortable position of having to wait for the proverbial check in the mail. By mid-September he was even more desperate for funds. On September 18, 1917, he wrote to Burdukov that he would like to borrow 14,000 rubles from him. Apparently permission from the Mongolian government is needed to transfer the money out of the country, and he planned to make a formal request to the Russian Consulate in Örgöö, asking that they acquire the proper authorization from the Mongolian authorities. He states again, this time emphatically, that he has no intention of returning to Mongolia. Why would Burdukov be willingly to loan what was then a considerable sum of money to a man with no apparent source of livelihood, who lived thousands of miles away, and who had no intention of returning to Mongolia? Why would the Mongolian government, which had been only too happy to be rid of Dambijantsan, be willing to authorize such a loan?

Meanwhile, on October 25 (Julian Calendar) Bolshevik Red Guards seized the headquarters of the Provincial Government in the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, triggering the Second Revolution setting in motion a civil war which was to last until 1922 when the Soviet Union was created. In his next letter, dated December 23, Dambijantsan makes no direct mention of the October Revolution, noting only that “it is still quiet and peaceful in Astrakhan city, as well as the whole province,” and that prices of mutton, beef, butter, and flour have soared even higher since he last wrote. The main reason for this letter is to thank Burdukov for forwarding via the Russian Consul in Örgöö 1000 rubles, apparently an advance on the 14,000 ruble loan he had requested. Gushed the Two White Camel Lama:

“I am grateful to you,” and I am really delighted to hear about your good health and the friendly efforts you have made on my behalf. I had been worrying about you and your health since I hadn’t heard from you for so long. There is no one dearer than you for me in this world, you are my only faithful friend forever.”

He also has nothing but kind words for the Russian Consul in Mongolia. It is not clear if this is the same official who had earlier arrested him; if so, all is now forgotten:

Could you pass my regards and gratitude to Mr. [[[Wikipedia:Russian|Russian]]] Consul for his help to me in difficult time, he was the one who pitied me when I was in difficult condition, sending the money he . . . please tell Mr. Consul that I would be grateful to him till the end of my life, that I would never forget his kindness and could you also ask him if he could send me the rest of the money.

As soon as he gets the entire 14,000 rubles, he goes on, he intends to buy a house near the Kalmyk Bazaar about seven miles from Astrakhan. Here, he claims, he intends to “settle down.” The Bolshevik Revolution does not seem to be worrying him unduly at this point, and he once again makes it clear—at least in writing—that he has no intention of returning to Mongolia. Intriguingly he adds: “As you suggested, I have started taking notes and writing down my life experiences up until now. I will I will be able to send these to you in the spring, as soon I finish them.” Was the mysterious badarchin finally going to lift the veil from his myth-strewn life? Would his memoirs shed light on his past, or would they, like the self-serving accounts of maguses like Madame Blavatsky and George Gurdjieff, simply add another layer to the obfuscation? If he did start his memoirs they have not survived

On December 23 Dambijantsan writes again to Burdukov in much the same vein. He has received another 1000 rubles and is waiting for the remaining 12,000. Here he says, confusingly, that the money is not a loan from Burdukov but instead funds owed to him by the Mongolian government. “Transfer the money as quickly as possible,” he pleads, “as I would like to stay forever in Astrakhan, living among the Kalmyks. I would like to buy a house for 4000 rubles near the Kalmyk Bazaar, seven miles from Astrakhan town; flats are very expensive here in the city.”

Dambijantsan’s final letter from Astrakhan is dated February 5, 1918. Civil war has broken out in Astrakhan. On one side are Astrakhan Cossacks, with whom most and the Kalmyks have sided, and on the other is a garrison of soldiers and local workers loyal to the Bolsheviks. The soldiers and workers barricaded themselves in building in the middle of the city and fighting raged for eigthteen days. Dambijantsan:

There were almost 800 Cossacks, with 200 officers . . .and about 1200 soldiers and workers. The Cossacks were armed with twelve field guns, thirteen machine guns and many rifles. The soldiers were armed with rifles and machine guns. The soldiers won the fight. The best part of the center of Astrakhan town has been burnt. Many shops and stores have been robbed by looters. There has been a loss of several millions of rubles. Lots of people-—fighters and peaceful citizen alike—died, about two and a half thousand people. . . Everywhere there is huge unemployment. The capital of all the merchants and the rich have been confiscated.

He has not received the 1200 rubles he was expecting and is in dire straits. Prices of all commodities are now outrageous. “Everything is so expensive I cannot afford anything.” He finally did receive at least some of the money owned him, but here was no longer any question of buying a house and settling down in Astrakhan. The soldiers and workers had established a Soviet and taken tentative control of the region but the civil war was far from over. Astrakhan was not longer a safe haven. Dambijantsan gathered up what money he had and sometime March took the Trans-Siberian Railroad east. Somewhere near Lake Baikal he bought a horse and headed south along the Selenge Valley into Mongolia.

The last and most dramatic chapter of the Ja Lama’s life was about to begin.

I wrote earlier about the Siege of Khovd and Munjaviin Ulaan, where Dambijantsan had established his headquarters in 1913. By the beginning of 1914 Dambijantsan’s reign of terror had antagonized many of his former supporters in western Mongolia. According to the Diluv Khutagt, “The people of the Banners of that region were unable to sleep in peace, and secretly went to the Russians with a petition of complaint” accusing Dambijantsan of “autocratic and despotic behaviour.” The complaint was presented to the Russian consul in late January of 1914 by several western Mongolian princes, including the Bayad Noyon, the chieftain of the Bayad people who had earlier befriended Dambijantsan. They believed he was a Russian citizen and that therefore it was the responsibility of the Russian authorities to somehow rein him in.

As we have seen, Russia had enjoyed the right of extraterritoriality in Mongolia during the time when the Qing Dynasty controlled the country. It was under the laws of extraterritoriality, which gave Russia authority over its own citizens in Mongolia, that Dambijantsan was arrested and deported back in 1891. It is not clear if these rights of extraterritoriality still pertained in the newly independent Mongolia ruled by the [[Wikipedia:Jebtsundamba Khutuktu|Bogd Gegeen, but in these unsettled times the niceties of international law might well have been overlooked. In western Mongolia Dambijantsan had clearly become a law onto himself and perhaps extra-legal measures were necessary to deal with the extraordinary menace he represented.

In response to the complaint a detachment of eighty Cossack under the command of one Captain Bulatov was dispatched from the Russian border town of of Khöshöö Mod. On February 8, 1914, they suddenly appeared at Muunjaviin Ulaan and surrounded Dambijantsan’s ger. Apparently he was arrested without a struggle. Searching his ger, the Cossacks discovered two complete human skins of people who had been flayed alive by his orders. One of the skins reportedly was that of Khaisan, the Kazakh chieftain with whom Dambijantsan had been feuding with earlier. The human skins along with a chest of silver and other items in his ger were confiscated.

Dambijantsan was taken under arrest to Khovd City and hauled up before the Russian consul. The consul recognized Dambijantsan as an “Astrakhan Kalmyk” going by the name of Amar Sanaev. As mentioned before, it is unclear whether this was his real name or if he just had forged documents to this effect. On March 7, 1914 an official connected with the Russian Consulate, A. Ya. Miller, filed a dispatch with the details of Dambijantsan’s arrest directly to the attention of the Minister of Foreign Affairs in St. Petersburg, S. D. Sazunov, which one historian claims “testifies to the great importance attached to the arrest of the despotic adventurer by the Russian government.” The official charges against Dambijantsan were at this point unclear. Possible charges included complicity in murder, if not murder itself, kidnapping, torture, and theft, to name a few. The first point of business, however, was to deport him in back to Russia.

Under escort he was taken first to the city of Biisk, the first large Russian town northwest of Mongolia. After a short stay in Biisk he was transferred to Tomsk, a major city on the Tom River, a tributary of the Ob, where he was incarcerated for a year. For someone who stood accused, if not convicted, of a host of crimes and misdemeanors he seemed to have a pretty easy regime. As he later wrote to Burdukov, “In the city of Tomsk I lived alone and was in a prison the whole time. But thanks be to God, the chief of the prison was a very kind man. It wasn’t that bad for me to live there; indeed it was even good for me.”

Then he was transferred to the Aleksandrovsky Central Prison, located on the steppe in the Irkutsk region west of Lake Baikal. This notorious penal colony provided much of the labor for the construction of the difficult Lake Baikal section of the Trans-Siberian Railroad, and also served as a transit point from which prisoners from Russia where sent on to other destinations within the vast prison network of East Siberia. After a brief stay here he sent to the city of Yakutsk, capital of in the immense province of Yakutia (now the Sakha Republic, part of the Russian Federation). Since some sources say he was “exiled” to Yakutsk, it is not clear whether was actually imprisoned or simply living as an exile in the city. He himself later told Burdukov that he lived in Yakutsk City, with no mention made of prison. Exile in Yakutia, ferociously cold in winter (the coldest temperature ever in the Northern Hemisphere, 90 below Fº, was recorded here), plagued by mosquitoes and flies in summer, and lacking any but the simplest amenities, was considered by many to be just as bad as imprisonment in other parts of the country. But again Dambijantsan did not seem to be suffering greatly, although he claimed that he did mind the cold. He later wrote, “It was not so bad for me there either”—perhaps he found solace in the arms of the legendarily sensuous Yakutian women—“but the weather was really cold—it sometimes got minus 65 degrees of centigrade [–85 Fº]” After one winter in Yakutia he had had enough. “Because of the freezing weather,” he later wrote in a letter, “I had to ask the appropriate people to transfer me somewhere else where it is warmer. As a result I was transferred to the city of Astrakhan”.

Again we must ask just what were the terms of Dambijantsan’s confinement and exile. The very mention of prison and exile in Siberia under the Czars conjures up visions of the knout, of cracking whips and clanking chains, of endless toil under the most brutal and degrading conditions—the world so evocatively called up in Dostoevsky’s The House of Dead—yet by his own admission Dambijantsan was not treated badly and most astonishingly seems capable of arranging his own transfers when he doesn’t find the weather to his liking. Clearly Dambijantsan was no ordinary prisoner destined to rot in the wastes of Siberia.

So he arrived in Astrakhan, the ancient city on the east bank of the Volga near where the river debouches into the Caspian Sea. Although Astrakhan itself is on the well-watered delta of the Volga River, the adjacent areas are arid steppes and deserts of scant grass and gravel flats dotted with wormwood and camel thorn. In the summer temperature can reach 100º F and like Yakutsk the city of Astrakhan was in summer infested by plagues of gnats, mosquitoes and flies. Here the recent arrival from Siberia found that it was too hot.

While traveling in Gov-Altai Aimag of Mongolia, which as we shall soon see was a major staging ground for Dambijantsan’s next appearance in Mongolia and where still live the children and grandchildren of people who actually knew the monk-adventurer, I heard a curious legend stating that in cold places Dambijantsan always felt uncomfortably hot, while in hot places he always suffered from chills. This legend referred specifically to his time under arrest and in exile. Thus, according to this legend, in Yakutia he was actually too hot and in Astrakhan he was too cold, and not vice-versa. Supposedly Dambijantsan himself had made this claim. Perhaps this was just one more attempt to create an air of mystery about himself, or perhaps others just wanted to further embroider the host of myths about the man.

In a letter to Burdukov in far-off Mongolia dated March 18, 1917, Dambijantsan wrote, “It was also not miserable to live in Astrakhan, but anyway I couldn’t stay there for long: the weather was humid and I couldn’t drink the water. Therefore I asked the chief of the province to transfer me to a distant town of the province, and I was sent to Tsarev town, where I am staying now.”

Tsarev is the current-day town of Akhtubinsk, 145 miles up the Volga River from Astrakhan, near the current city of Volgograd (Stalingrad). Tsarev—located near one of the capitals of the Golden Horde, founded by Chingis Khan’s grandson Batu —was on the Pontic-Caspian Steppe, north of the Caspian Lowland Desert, and was slightly milder in temperature and considerably less humid.

So yet again Dambijantsan was able to arrange his transfer to more hospitable climes. And there was no more question of confinement in prison. He was apparently required to register with the local authorities and may not have been free to leave the Astrakhan gubernaria, in which Tsarev was located, but otherwise he was free to come and go as he pleased. Renting lodging from a “very kind and pleasant person” named Zlobinov, he quickly settled in and was soon writing to Burdukov “I really like life here.”

Curiously, he admits that he had trouble speaking Russian. This admission only deepens the mystery about Dambijantsan’s linguistic abilities. He was born (apparently) on Russian territory but was not ethnically Russian, and may have left Russia to become a monk when he was a small boy, so he can perhaps be excused for not learning Russian as a child. But later he worked for Russian expeditions, traveled extensively through areas where Russian was a lingua franca, came into contact with many Russians, not the least of which was Burdukov, while in Mongolia, and had just spent over two years in the Russian prison system, and yet by his own admission he had trouble communicating in Russian with the people of Tsarev, where he was now living. Although he is now in his fifties he even engages Zlobinov to give him lessons in reading and writing Russian.

Dambijantsan also admitted that “I am having a little problem with money. . .” This is understandable, since he had apparently been hauled out of Mongolia with only the shirt on the back and had spent the last two years in prison. What was he living on in Tsarav? Supposedly all of his property at Munjaviin Ulaan had been been confiscated, including livestock, gers, considerable amounts of silver, and other personal possessions Dambijantsan had also loaned out large amounts of silver to local officials and individuals. After his arrest local officials apparently tried to collect these loans. But what had happened to the wealth he had gathered during his years in Mongolia? Had the Russian consul seized it, or the Mongolian government? It would appear that the Russian consul seized at least some of his possessions. On March 18, 1917 we see Dambijantsan writing to Burkudov that he “was very pleased with the Consul for his efforts in sending me money.” Why was the Russian consul sending him money? Had some of the property which had seen seized at the time of his arrest been sold and the proceeds returned to him? If he was a criminal why was he entitled to his ill-gotten gains? And Burdukov too appeared to be forwarding money to him, apparently the proceeds from some unspecified business deals. Even in far-off Astrakhan province Dambijantsan seems to have kept his fingers in various pies in Mongolia.

Meanwhile the February Revolution of 1917 had erupted. Imperial Russia collapsed, Tsar Nicholas abdicated, ending the Romanov Dynasty, and as provisional government headed by Prince Georgi Lvov was sworn in. The Revolution soon made itself felt in Tsarev. Under the new Provisional Government the governor of the region, the chief of police, and various military leaders had been arrested. “As you know,” he tells Burdukov, “I was a criminal under the old regime. But now I am supposed to get a pardon. As soon as my pardon comes through I will come and visit you.” He also asks Burdukov to send him some photos of himself dressed in traditional Mongolian clothing. “That would be very interesting for me,” he notes.

But the situation in Tsarev kept deteriorating. The government was in chaos and inflation had gone through the roof. Although apparently still under police supervision, Dambijantsan was not longer obliged to stay to stay in Tsarev. He does not give the exact reasons for his move, but in early May he traveled down the Volga, arriving in Astrakhan on May 12, 1917. Here he took lodging in District #4, on Sado-Aptekar Street, at the house of a man named Verenin.

By Dambijantsan’s time the city was still dominated by the Kremlin, located on a low hill a quarter of a mile from the east bank of the Volga. Above the walls of the Kremlin soared the green and gold onion-shaped domes of the Ascension Cathedral and the Trinity Cathedral, both built around the beginning of the 18th century. About a third of a mile north of the Kremlin a narrow canal runs east from the Volga, eventually connecting with another canal which branches off from the Volga south of the Kremlin. Sado-Aptekar Street, where Dambijantsan lived, is one block beyond the northern canal. It was probably not one of the best neighborhoods. Although close to downtown, it was on the other side of the canal, the Astrakanian equivalent to the wrong side of the tracks. It was a neighborhood were a man in exile and still technically under police supervision could find lodging without attracting too much attention.

I crossed one of the footbridges across the canal and followed the northern embankment to Kalinin Street. The embankment here is lined with new and restored commercial buildings and up-scale apartment houses. I turned right on Kalinin Street and walked two blocks north to Pestelya Street, the current name of Sado-Aptekar Street, which runs parallel to the canal. Pestelya Street is only four blocks long. To the south of Pestelya Street is the embankment, and to the east, west, and north are Soviet-era and later, more up-scale high-rise apartments buildings.

Turning off Kalinin Street I am surprised to see that Pestelya Street, completely unlike the surrounding area, is lined with very old two-story wooden houses. I am seized by the uncanny feeling that I have stepped through a time warp and emerged into the nineteenth century. The street is like a time capsule embedded in modern Astrakhan. Many of the building are dilapidated, but still clearly lived in, although at the moment the street is eerily deserted. The only hints of modernity are a few rusty air-conditioner units hanging out of second-story windows. There is now no way to determine which was the house of Verenin where Dambijantsan lived. In his letters from here he does not give a house number and in any case the house numbering system may have changed since then. Still I walk the entire four-block length of the street, peering through ancient wooden gates into courtyards, some with tiny kitchen gardens, and stopping to photograph the more unusual buildings. Dambijantsan had lived in one of the buildings on this street and it was no doubt here that he plotted his final return to Mongolia. Eventually I do pass a few people, shabbily dressed Russians, but they pay not the slightest attention to me, as if they do not even see me.

During my travels in Mongolia I met many people who believed that the spirit of Dambijantsan continues to haunt his former hangouts. Preposterous as it may sound, I could not shake the feeling that Dambijantsan, in one manifestation or another, had cast a spell over this odd, anachronistic street. Turning south on Kalinin Street I am suddenly back in modern-day Astrakhan. The shade of Dambijantsan was hopefully left behind.