The Art of Tibetan Esoteric Buddhism

The art of Esoteric Buddhism grew and flourished with the spread of Buddhism in Tibet. Closely linked with the doctrine of Esoteric Buddhism in theme, technique and the use of colour, it serves the purpose of religious propaganda and is believed to function with "supernatural powers". It has gone through three stages of development.

The introduction of Buddhism into Tibet in the early 7th century was followed by the building of many temples and monasteries as a result of the royal endorsement of the religion. During this period, the Qoikang and Ramoqe lamaseries, the Potala Palace and a number of lesser temples were constructed. The awareness of the potentialities of the monasteries as social institutions and the effort to create a mystic religious atmosphere eventually led to the production in large quantity of images of the Buddha, religious frescos and paintings for use in temples and monasteries.

This period was also a time when the highly developed feudal culture of the Hans began to wake its impact on Tibetan culture, and the craftsmanship brought into Tibet by Han craftsmen played an important role in accelerating the growth of Buddhist culture in Tibet. Meanwhile, many of the Exoteric and Esoteric canonical texts in Sanskrit were translated into the Tibetan language. For example, the Tibetan version of the Silpakarmasthana-vidya, a book on the rules and methods for the construction of temples, stupas and Buddhist images and on the techniques of making mandalas, introduced new notions and techniques to the art of Tibetan Esoteric Buddhism.

These were the external factors that contributed much to the shaping and development of Esoteric Buddhist art. However, in the 200 years from the 7th to the 9th centuries, the repeated outbursts of rebellion against Buddhism by the Bonpos played havoc with Buddhist culture, and few works of art of early Tibetan Esoteric Buddhism survived these violent attacks. This was the first stage that marked the beginning of Buddhist art in Tibet.

The years from 978 on saw a vigorous revival of Buddhism in Tibet and as a feudal economy had by then emerged, Buddhist art made an impressive progress as was shown in the building of more temples and monasteries. It was a time when all Buddhist sects in Tibet and their sub-sects founded monasteries of their own. For instance, the Sagya, Drepung and Zhaxilhunbo monasteries were built all imposing and magnificent structures with a warehouse of finely-made objects of Buddhist art.

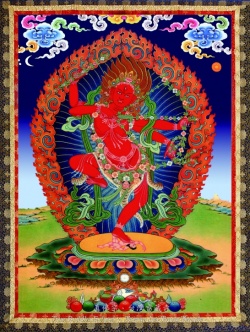

Incomplete statistics show that no fewer than 60 huge main halls and 200 prayer halls were built in the lamaseries. Frescoes and thangkas (cloth painting) were created by the thousand in addition to innumerable images of Buddhist deities and carved objects of art. This period also saw the emergence of the distinguished style of painting known in the history of Tibetan Buddhist art as "the Gyangze School", so called because Gyangze was the birthplace of most of its artists, whose style was heavily influenced by Nepalese art of painting. This was the second stage of development, a period that produced far- reaching influence with its remarkable achievement in Tibetan Buddhist culture and art.

Tibetan Buddhist art entered its third stage of development at the end of the 17th century. During this period, ancient monasteries were extended or renovated. The Potala Palace after extension soared to a majestic height of 117.19 metres with its main building, a sight that inspired awe and admiration. The palace at the time already had up to 1,000 rooms, and its crisscrossing and covered walkways made it look like a labyrinth. The entire palace was decorated with frescoes, coloured paintings, wood and stone carvings and gold and silver ornaments, all of which reached an extremely high level in artistic execution.

The stupa of the Fifth Dalai is 14.85 metres in height. Nearly 6,000 kilo-grammes of pure gold were used to paint it from top to bottom, and inlaid in this layer of gold were a total of about 18,000 pearls, precious stones and coral, amber and agate beads. It is a rare object of art superbly executed with a combination of skills of many different crafts. A number of gardens of a new design (for example, the Lubulyrika) and temples of Bhaisajyaraja (the Bodhisattva of Medicine) were also built in this period.

The works of art related to Tibetan Esoteric Buddhism, which absorb the influences of Han, Indian and Nepalese art, maintain their own characteristic style, which is discernible in all their forms of artistic expression. Take, for example, the roofs of temples. There, decorating the flying cornices are not only finely carved miniature gods, recumbent deer, the Wheel of the Law, golden banners, dragons, phoenixes and lions that show the influences of ancient architecture of the Tang and Song dynasties, but also pagodas, inverted bells and lotus bases that might have been sitting on the roofs of Indian or Nepalese temples.

No artist will begin his work on any image of the Buddha, or on any picture, clay figure, wood or stone block without first selecting an auspicious day. He will then bathe himself, burn incense sticks, pray and meditate. Such rituals become even more important, more complicated and more mystic in the case of the construction or renovation of temples. That religious seriousness lies behind all the art works of Tibetan Buddhism, particularly those of Tibetan Esoteric Buddhism.