Buddha

Click here to see other articles relating to word Buddha

Buddha (Skt. Buddha; Tib. སངས་རྒྱས་, Sangyé; Wyl. sangs rgyas), usually refers to Shakyamuni Buddha, the Indian prince Gautama Siddhartha, who reached enlightenment in the sixth century B.C., and who taught the spiritual path followed by millions all over Asia, known today as Buddhism. Buddha, however, also has a much deeper meaning.

It means anyone who has completely awakened from ignorance and opened to his or her vast potential for wisdom. A buddha is one who has brought a final end to suffering and frustration and discovered a lasting and deathless happiness and peace.

Buddha (sangs rgyas): One who has eliminated the two veils - the veils of emotional obscuration and cognitive obscuration, which is the dualistic conceptual thinking, which obscures natural omniscience - and who has developed the two wisdoms, the wisdom which knows this ultimate nature of mind and phenomena, and the wisdom which knows the multiplicity of these phenomena.

- The first of the Three Jewels (Skt. triratna), which are the foremost objects of refuge, in Buddhism. The Sanskrit term buddha literally means "awakened", "developed", and "enlightened", while its Tibetan equivalent sangs rgyas is a combination of sangs pa ("awakened" or "purified"), and rgyas pa ("developed").

These two syllables therefore denote a full awakening from fundamental ignorance (Skt. - avidyā) in the form of the two obscurations (dvayāvaraṇa) and a full realization of true knowledge, ie. the pristine cognition (jñāna) of buddha-mind.

A fully awakened being is herein one who, as a result of training the mind through the bodhisattva paths, has finally realized this full potential for complete enlightenment (bodhi), and has eliminated the obscuration to true knowledge and liberation.

Buddhas are characterized according to their five fruitional aspects of Buddha-body (kaya), Buddha-speech (vāk), Buddha-mind (citta), Buddha-qualities (guṇa), and Buddha-activities (kötyakriyā), which are poetically described in the literature of the Nyingma school as the "five wheels of inexhaustible adornment" (mi zad pa'i rgyan gyi 'khor lo lnga).

For a detailed explanation of these five aspects, see Dudjom Rinpoche's, The Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism

Etymology

The Tibetan term for Buddha, སངས་རྒྱས་, Sangyé, is explained as follows:

- སངས་, Sang means ‘awakening’ from the sleep of ignorance, and ‘purifying’ the darkness of both emotional obscurations and cognitive obscurations.

- རྒྱས་, Gyé means ‘opening’, like a blossoming lotus flower, to all that is knowable, and ‘developing’ the wisdom of omniscience—the knowledge of the true nature of things, just as they are, and the knowledge of all things in their multiplicity.

The Seventy Verses on Taking Refuge says:

- One who sleeps no more in ignorance,

- And in whom genuine wisdom is brought forth,

- Has truly awoken as an awakened buddha,

- Just as one wakes from ordinary sleep.

As it says, ‘awakened’ means that ending the slumber of ignorance is like waking from sleep. And:

- Their minds have opened to all that is knowable,

- And they have overcome the tight seal of delusion,

- So the awakened have blossomed like lotus flowers.

As it says, they are like ‘blossoming’ lotus petals in the sense that through their genuine wisdom they have overcome the tendency to ‘shut down’ through lack of knowledge, and their minds are open to all that can be known.

Kayas & Wisdoms

[[Image:Samantabhadra.jpg|thumb|The Dharmakaya Buddha Samantabhadra)] Buddhas are spoken of in terms of the kayas and wisdoms.

Three Kayas

The three 'bodies' of a buddha. They relate not only to the truth in us, as three aspects of the true nature of mind, but to the truth in everything. Everything we perceive around us is nirmanakaya; its nature, light or energy is sambhogakaya; and its inherent truth, the dharmakaya.

Five Wisdoms

- wisdom of dharmadhatu

- mirror-like wisdom

- wisdom of equality

- wisdom of discernment

- all-accomplishing wisdom

Sogyal Rinpoche writes:

- You can also think of the nature of mind like a mirror, with five different powers or 'wisdoms.' Its openness and vastness is the wisdom of all-encompassing space [or dharmadhatu ], the womb of compassion.

Its capacity to reflect in precise detail whatever comes before it is the mirror-like wisdom.

Its fundamental lack of any bias toward any impression is the equalizing wisdom [or wisdom of equality).

Its ability to distinguish clearly, without confusing in any way the various different phenomena that arise, is the wisdom of discernment.

And its potential of having everything already accomplished, perfected, and spontaneously present is the all-accomplishing wisdom. [1]

These five wisdoms may be condensed into two:

- ‘the wisdom that knows the nature of all phenomena’ which comprises the wisdom of the dharmadhatu, mirror-like wisdom and the wisdom of equality; and

- ‘the wisdom that knows the multiplicity of phenomena’ which comprises discriminating and all-accomplishing wisdom.

They can all be condensed into a single wisdom: the wisdom of omniscience.

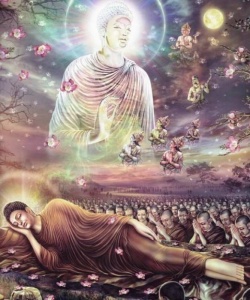

Twelve Deeds

[[Image:Buddha12deeds.jpg|thumb|The Twelve deeds of a Buddha)] Supreme nirmanakaya buddhas display the twelve deeds:

- the descent from Tushita, the Joyous pure land (dga' ldan gyi gnas nas 'pho ba),

- entering the mother’s womb (lhums su zhugs pa),

- taking birth[2] (sku bltams pa),

- becoming skilled in various arts (bzo yi gnas la mkhas pa),

- delighting in the company of royal consorts (btsun mo'i 'khor dgyes rol ba),

- developing renunciation and becoming ordained (rab tu byung ba),

- practicing austerities for six years (dka' ba spyad pa),

- proceeding to the foot of the bodhi tree (byang chub snying por gshegs pa),

- overcoming Mara’s hosts (bdud btul ba),

- becoming fully enlightened (mngon par rdzogs par sangs rgyas pa),

- turning the wheel of Dharma (chos kyi 'khor lo bskor ba), and

- passing into mahaparinirvana [3] (mya ngan las 'das pa)

Qualities

Eight Qualities of a Buddha

[[Image:Maitreya.jpg|thumb|Maitreya, the future Buddha)] The qualities of a Buddha are immeasurable. Yet according to Maitreya's Uttaratantra Shastra, they can be condensed in eight qualities of the two-fold benefit of self and others:

1) Self-arisen wisdom

2) Unconditioned body

3) Spontaneously perfect

Benefit of others:

And 7) the benefit of self and 8) the benefit of others.

How a Buddha teaches

When the teacher is a fully enlightened buddha, he teaches through his three types of miraculous ability. [4]

Footnotes

- ↑ The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, p. 157

- ↑ In the case of Buddha Shakyamuni, this was in the Lumbini garden.

- ↑ In the case of Buddha Shakyamuni, this was in the city of Kushinagara.

- ↑ Patrul Rinpoche, Preliminary Points To be Explained when Teaching the Buddha's Word or the Treatises, translated by Adam Pearcey.

See Also

Further Reading

- Khenpo Ngawang Palzang, A Guide to the Words of My Perfect Teacher, Shambhala, 2004, pages 101-107.

Source

Buddha

仏 (Skt, Pali; Jpn hotoke or butsu )

One enlightened to the eternal and ultimate truth that is the reality of all things, and who leads others to attain the same enlightenment. Buddha was originally a common word meaning awakened one or enlightened one, referring to those who attained any kind of religious awakening. In Buddhism, it refers to one who has become awakened to the ultimate truth of all things and phenomena.

In this context, the term Buddha at first was applied exclusively to Shakyamuni. Later, however, with the development of Buddha as an ideal, numerous Buddhas appeared in Mahayana scriptures. These include such Buddhas as Amida and Medicine Master.

Expressions such tences" communicate the idea that Buddhas, or the potential for enlightenment they represent, pervade the universe and are eternally present.Various definitions of Buddha are set forth in Buddhist teachings. In Hinayana teachings, it means one who has entered the state of nirvana, in which both body and mind are extinguished.

Mahayana teachings generally maintain that one becomes a Buddha only after innumerable kalpas of austere and meritorious practices, by eradicating illusions and earthly desires and acquiring the thirty-two features of a Buddha.

The Lotus Sutra views Buddha as one who manifests the three virtues of sovereign, teacher, and parent, who is enlightened to the true aspect of all phenomena,

and who teaches it to people to save them from suffering. Philosophy based on the Lotus Sutra, including that of T'ient'ai and Nichiren who regarded the sutra as Shakyamuni's most profound teaching, recognizes the potential of every person to become a Buddha.

See Silent Buddha.

Source

Buddha is a title meaning ‘Awakened One’ which Siddhattha Gotama called himself and was called by others after he attained Enlightenment. More than an individual, a Buddha is a type, a human who has reached the apex of Wisdom and Compassion and is no longer subject to Rebirth.

A Buddha attains Enlightenment entirely on his own, whereas an Arahat does it as a result of listening to and practising the teachings of a Buddha.

The Buddha of our present era is Siddhattha Gotama, but tradition says that there were other Buddhas in previous eras just as there will be Buddhas in future eras.

When the truth of the Dhamma becomes lost or obscured, someone will sooner or later rediscover it and such a person will be called a Buddha.

Source

1. Buddha

A generic name, an appellative - but not a proper name - given to one who has attained Enlightenment (na mātarā katam, na pitarā katam – vimokkhantikam etam buddhānam bhagavantānam bodhiyā mūle ... paññatti, MNid.458; Ps.i.174) a man superior to all other beings, human and divine, by his Knowledge of the Truth (Dhamma).

The texts mention two kinds of Buddha: viz.,

- Pacceka Buddhas - i.e., Buddhas who also attain to complete Enlightenment but do not preach the way of deliverance to the world; and

- Sammāsambuddhas, who are omniscient and are teachers of Nibbāna (Satthāro).

The Commentaries, however (e.g., SA.i.20; AA.i.65) make mention of four classes of Buddha:

All Arahants (khīnāsavā) are called Catusacca Buddhā and all learned men Bahussuta Buddhā.

A Pacceka Buddha practises the ten perfections (pāramitā) for two asankheyyas and one hundred thousand kappas, a Sabbañu Buddha practises it for one hundred thousand kappas and four or eight or sixteen asankheyyas, as the case may be (see below).

Seven Sabbaññu Buddhas are mentioned in the earlier Books; these are

E.g., D.ii.5f.; S.ii.5f.; cp. Thag.491; J.ii.147; they are also mentioned at Vin.ii.110, in an old formula against snake bites. Beal (Catena, p. 159) says these are given in the Chinese Pātimokkha. They are also found in the Sayambhū Purāna (Mitra, Skt. Buddhist Lit. of Nepal, p. 249).

This number is increased in the later Books. The Buddhavamsa contains detailed particulars of twenty five Buddhas, including the last, Gotama, the first twenty four being those who prophesied Gotama's appearance in the world. They are the predecessors of Vipassī, etc., and are the following:

- Dīpankara,

- Kondañña,

- Mangala,

- Sumana,

- Revata,

- Sobhita,

- Anomadassī,

- Paduma,

- Nārada,

- Padumuttara,

- Sumedha,

- Sujāta,

- Piyadassī,

- Atthadassī,

- Dhammadassī,

- Siddhattha,

- Tissa and

- Phussa.

The same poem, in its twenty seventh chapter, mentions three other Buddhas - Tanhankara, Medhankara and Saranankara - who appeared in the world before Dīpankara.

The Lalitavistara has a list of fifty four Buddhas and the Mahāvastu of more than a hundred.

The Cakkavatti Sīhanāda Sutta (D.iii.75ff ) gives particulars of Metteyya Buddha who will be born in the world during the present kappa.

The Anāgatavamsa gives a detailed account of him. Some MSS. of that poem (J.P.T.S. 1886, p. 37) mention the names of ten future Buddhas, all of whom met Gotama who prophesied about them.

These are Metteyya, Uttama, Rāma, Pasenadi Kosala, Abhibhū, Dīghasonī, Sankacca, Subha, Todeyya, Nālāgiripalaleyya (sic).

The Mahāpadāna Sutta (D.ii.5f ) which mentions the seven Buddhas gives particulars of each under eleven heads (paricchedā) -

- the kappa in which he is born,

- his social rank (([[[Jāti]])]),

- his family (gotta),

- length of Life at that epoch (āyu),

- the tree under which he attains Enlightenment (Bodhi),

- the names of his two chief disciples (sāvakayuga),

- the numbers present at the assemblies of Arahants held by him (sāvakasannipāta),

- the name of his personal attendant (upatthākabhikkhu),

- the names of his father and mother and of his birthplace.

The Commentary (DA.ii.422ff) adds to these other particulars -

- the names of his son and his wife before his Renunciation,

- the conveyance (yāna) in which he leaves the world,

- the monastery in which his Gandhakuti was placed,

- the amount of money paid for its purchase,

- the site of the monastery, and the name of his chief lay patron.

In the case of Gotama, the further fact is stated that on the day of his birth there appeared also in the world Rāhulamātā, Ananda, Kanthaka, Nidhikumbhi (Treasure Trove), the Mahā Bodhi and Kāludāyī.

Gotama was conceived under the asterism (nakkhatta) of Uttarāsālha, under which asterism he also made his Renunciation (Da.ii425), preached his first sermon and performed the Twin Miracle.

Under the asterism of Visākha he was born, attained Enlightenment and died; under that of Māgha he held his first assembly of Arahants and decided to die; under Assayuja he descended from Tāvatimsa.

The Buddhavamsa Commentary says (BuA.2f) that in the Buddhavamsa particulars of each Buddha are given under twenty two heads, the additional heads being the details of the first sermon, the numbers of those attaining realization of truth (abhisamaya) at each assembly,

the names of the two chief women disciples, the aura of The Buddha's Body (ramsi), the height of his Body, the name of the Bodhisatta (who was to become Gotama Buddha), the prophecy concerning him, his exertions (padhāna) and the details of each Buddha's Death.

The Commentary also says that mention must be made of the time each Buddha lived as a Householder, the names of the palaces he occupied, the number of his Dancing women, the names of his chief wife, and his son, his conveyance, his renunciation, his practice of austerities, his patrons and his monastery.

There are eight particulars in which the Buddhas differ from each other (atthavemattāni).

These are length of Life in the epoch in which each is born, the height of his Body, his social rank (some are born as khattiyas, others as brahmins), the length of his austerities, the aura of his Body (thus, in the case of Mangala, his aura spread throughout the ten thousand world systems, while that of Gotama extended only one fathom; - but when he wishes, a Buddha can spread his aura at will, BuA.106); the conveyance in which he makes his renunciation, the tree under which he attains Enlightenment, and the size of the seat (pallanka) under the Bodhi tree.

Only the first five are mentioned in DA.ii.424; also at BuA.105; all eight are given at BuA.246f., which also gives details under each of the eight heads, regarding all the twenty five Buddhas.

In the case of all Buddhas, there are four fixed spots (avijahitatthānāni). These are:

- the site of the seat under the Bodhi tree (bodhipallanka),

- the Deer Park at Isipatana where the first sermon is preached,

- the spot where The Buddha first steps on the ground at Sankassa on his descent from Tusita (Tāvatimsa?)

- the spots marked by the four posts of the bed in The Buddha's Gandhakuti in Jetavana.

The monastery may vary in size; the site of the city in which it stands may also vary, but not the site of the bed. Sometimes it is to the east of the Vihāra, sometimes to the north (DA.ii.424; BuA.247).

Thirty facts are mentioned as being true of all Buddhas (samatimsavidhā dhammatā).

- In his last Life every Bodhisatta is conscious at the moment of his conception;

- in his mother's womb he remains cross legged with his face turned outwards;

- his mother gives birth to him in a standing posture;

- the birth takes place in a forest grove (araññe);

- immediately after birth he takes seven steps to the north and roars the "lion's roar";

- he makes his renunciation after seeing the four omens and after a son is born to him;

- he has to practise austerities for at least seven days after donning the yellow robe;

- he has a meal of milk rice on the day of his Enlightenment;

- he attains to omniscience seated on a carpet of grass;

- he practises Concentration in breathing;

- he defeats Māra's forces;

- he attains to supreme perfection in all Knowledge and virtue at the foot of the Bodhi tree;

- Mahā Brahmā requests him to preach the Dhamma;

- he preaches his first sermon in the Deer Park at Isipatana;

- he recites the Pātimokkha to the fourfold assembly on the full moon day of Māgha;

- he resides chiefly in Jetavana, he performs the Twin Miracle in Sāvatthi;

- he preaches the Abhidhamma in Tāvatimsa;

- he descends from there at the gate of Sankassa;

- he constantly lives in the bliss of phalasamāpatti;

- he investigates the possibility of converting others during two jhānas;

- he lays down The Precepts only when occasion arises for them;

- he relates Jātakas when suitable occasions occur;

- he recites the Buddhavamsa in the assembly of his kinsmen;

- he always greets courteously monks who visit him;

- he never leaves the place where he has spent the rainy season without bidding farewell to his hosts;

- each day he has prescribed duties before and after his meal and during the three watches of the night;

- he eats a meal containing flesh (mamsarajabhojana) immediately before his Death;

- and just before his Death he enters into the twenty four crores and one hundred thousand samāpattī.

There are also mentioned four dangers from which all Buddhas are immune:

- no misfortune can befall the four requisites intended for a Buddha;

- no one can encompass his Death;

- no injury can befall any of his thirty two Mahāpurisalakkhanā or eighty anubyañjanā;

- nothing can obstruct his aura (BuA.248).

A Buddha is born only in this Cakkavāla out of the ten thousand Cakkavālas which constitute the jātikkhetta (AA.i.251; DA.iii.897). There can appear only one Buddha in the world at a time (D.ii.225; D.iii.114; the reasons for this are given in detail in Mil. 236, and quoted in DA.iii.900f).

No Buddha can arise until the Sāsana of the previous Buddha has completely disappeared from the world. This happens only with the dhātuparinibbāna (see below).

When a Bodhisatta takes conception in his mother's womb in his last Life, after leaving Tusita, there is manifested throughout the world a wonderful radiance, and the ten thousand world systems tremble.

Similar earthquakes appear when he is born, when he attains Enlightenment, when he preaches the first sermon, when he decides to die, when he finally does so (D.ii.108f.; cp. DA.iii.897).

The Mahāpā Dāna Sutta (D.ii.12-15) and the Acchariya-bbhuta-Dhamma Sutta (M.iii.119-124) contain accounts of other miracles, which attend the conception and birth of a Buddha.

Later Books (e.g., J.i.) have greatly enlarged these accounts.

They describe how the Bodhisatta,

having practised the thirty Pāramī, and made the five great gifts (pañcamahāpariccāgā),

- and thus reached the pinnacle of the threefold cariyā - ñātattha-cariyā,

- lokattha-cariyā and buddhi-cariyā - gives the seven mahādānā,

as in the case of Vessantara, making the earth tremble seven times, and is born after Death in Tusita.

The Bodhisatta, who later became Vipassī Buddha, remained in Tusita during the whole permissible period - fifty seven crores and sixty seven thousand years.

But most Bodhisattas leave Tusita before completing the full span of Life there.

Five signs appear to warn the devaputta that his end is near (see Deva);

the gods of the ten thousand worlds gather round him, beseeching him to be born on earth that he may become The Buddha. The Bodhisatta thereupon makes the five investigations (pañcamahāvilokanāni).

Sometimes only one Buddha is born in a kappa, such a kappa being called Sārakappa; sometimes two, Mandakappa; sometimes three, Varakappa; sometimes four, Sāramandakappa; rarely five, Bhaddakappa (BuA.158f).

No Buddha is born in the early period of a kappa, when men live longer than one hundred thousand years and are thus not able to recognize the nature of old age and Death, and therefore not able to benefit by his preaching. When the Life of man is too short, there is no time for exhortation and men are full of kilesa.

The suitable age for a Buddha is, therefore, when men live not less than one hundred years and not more than ten thousand. The Bodhisatta must first consider the continent and the country of birth.

Buddhas are born only in Jambudīpa, and there, too, only in the Majjhimadesa.

He must then consider the family; Buddhas are born only in brahmin or khattiya families, whichever is more esteemed during that particular age.

Then he must think of the mother: she must be wise and virtuous; and her Life must be destined to end seven days after The Buddha's birth.

Having made these decisions, the Bodhisatta goes to Nandanavana in Tusita, and while wandering about there "falls away" from Tusita and takes conception.

He is aware of his Death but unaware of his cuti-Citta or dying thought. The Commentators seem to have differed as to whether there is awareness of conception.

When the Bodhisatta is conceived, his mother has no further wish for indulgence in sexual pleasure. For seven days previously she observes the uposatha vows, but there is no mention of a virgin birth; the birth might be called parthenogenetic (see Mil.123).

On the day of the actual conception, the mother, having bathed in scented water after the celebration of the Asālha festival, and having eaten choice Food, takes upon herself the uposatha vows and retires to the adorned state bedchamber.

As she sleeps, she Dreams that the Four Regent Gods raise her with her bed, and, having taken her to the Himālaya, bathe her in Lake Anotatta, robe her in divine Clothes, anoint her with perfumes and deck her with heavenly Flowers (according to the Nidānakathā, J.i.50, it is their queens who do these things, re the Bodhisatta assuming the Form of an elephant, see Dial.ii.116n).

Not far away is a silver mountain and on it a golden mansion.

There they lay her with her head to the east.

The Bodhisatta, assuming the Form of a white elephant, enters her room, and after circling right wise three times round her bed, smites her right side with his trunk and enters her womb.

She awakes and tells her husband of her dream. Soothsayers are consulted, and they prophesy the birth of a Cakka-vatti or of a Buddha.

The two Suttas mentioned above speak of the circumstances obtaining during the time spent by the child in his mother's womb.

It is said (DA.ii.437) that the Bodhisatta is born when his mother is in the last third of her middle age. This is in order that the birth may be easy for both mother and child.

Various miracles attend the birth of the Bodhisatta.

The Commentaries expound, at great length, the accounts of these miracles given in the Suttas.

Immediately after birth the Bodhisatta stands firmly on his feet, and having taken seven strides to the north, while a white canopy, is held over his head, looks round and utters in fearless voice the lion's roar: "Aggo 'ham asmi lokassa, jettho 'ham asmi lokassa, settho 'ham asmi lokassa, ayam antimā Jāti, natthi dāni punabbhavo” (D.ii.15).

To the later Buddhists, not only these acts of the Bodhisatta, but every item of the miracles accompanying his birth, have their symbolical meaning.

See, e.g., DA.ii.439; thus, standing on the earth means the attaining of the four Iddhi-pādas; facing north implies the spiritual conquest of multitudes; the seven strides are the seven bojjhangas; the canopy is the umbrella of emancipation;

looking round means unveiled Knowledge; fearlessness denotes the irrevocable turning of the Wheel of the Law; the mention of the last birth, the arahantship he will attain in this Life, etc.

There seems to have been a difference of opinion among the Elders of The Sangha as to what happened when the Bodhisatta took his seven strides northwards.

Did he walk on the earth or travel through the air? Did people see him go?

Was he clothed? Did he look an infant or an adult? Tipitaka Culābhaya, preaching on the first floor of the Lohapāsāda, settled the question by suggesting a compromise: the Bodhisatta walked on earth, but the onlookers felt he was travelling through the air;

he was naked, but the onlookers felt he was gaily adorned; he was an infant, but looked sixteen years old; and after his roar he reverted to infancy! (DA.ii.442)

After birth, the Bodhisatta is presented to the soothsayers for their prognostications and they reassert that two courses alone are open to him either to be a Cakka-vatti or a Buddha.

They also discover on his Body the thirty two marks of the Great Man (Mahāpurisa) (These are given at D.ii.17 19; also M.ii.136f).

The Bodhisatta has also the eighty secondary signs (asīti anubyañjana) such as copper coloured nails glossy and prominent, sinews which are hidden and without knots, etc. (The list is found in Lal. 121 [106]).

The Brahmāyu Sutta (for details see M.ii.137f) gives other particulars about Gotama, which are evidently characteristic of all Buddhas. Thus, in walking he always starts with the right foot, his steps are neither too long nor too short, only his lower limbs move; when he gazes on anything, he turns right round to do so (nāgavilokana).

When entering a house he never bends his Body (Cp. DhA.ii.136); when sitting down, accepting water to wash his bowl, eating, washing his hands after eating, or returning thanks, he sits with the greatest propriety, dignity and thoroughness.

When preaching, he neither flatters nor denounces his hearers but merely instructs them, rousing, enlightening and heartening them (M.ii.139).

His voice possesses eight qualities: it is frank, clear, melodious, pleasant, full, carrying, deep and resonant; it does not travel beyond his audience (for details concerning his voice see DA.ii.452f.; and MA.ii.771f).

A passage in the Anguttara (A.iv.308) says that a Buddha preaches in the eight assemblies - of nobles, brahmins, householders, recluses, devas of the Cātummahārājika world, and of Tāvatimsa, of Māras and of Brahmās.

In these assemblies he becomes one of them and their Language becomes his.

The typical career of a Buddha is illustrated in the Life of Gotama. He renounces the world only after the birth of a son. This, the Commentary explains (DA.ii.422), is to prevent him from being taken for other than a human being.

He sees the four omens before his Renunciation: an old man, a sick man, a dead man, and a recluse.

Some Buddhas see all four on the same day, others, like Vipassī, at long intervals (DA.ii.457). On the night before the enlightenment, the Bodhisatta Dreams five Dreams (A.iii.240).

After the enlightenment The Buddha does not preach till asked to do so by Mahā Brahmā.

This is on order that the world may pay greater attention to The Buddha and his teaching (DA.ii.467).

A Buddha generally travels from the Bodhi tree to Isipatana for his first sermon, through the air, but Gotama went on foot because he wished to meet Upaka on the way (DA.ii.471).

The Buddha's day is divided into periods, each of which has its distinct duties (DA.i.45f; SNA.i.131f, etc.).

He rises early, and having attended to his bodily functions, sits in solitude till the time arrives for the alms round.

He then puts on his outer robe and goes for alms, sometimes alone, sometimes with a large following of monks.

When he wishes to go alone he keeps the door of his cell shut, which sign is understood by the monks (Ibid., 271).

Occasionally he goes long distances for alms, travelling through the air, and then only khīnāsavā are allowed to accompany him (ThagA.i.65). Sometimes he goes in the ordinary way (pakatiyā), sometimes accompanied by many miracles.

After the meal he returns to his cell; this is the pure bhattakicca.

Having washed his feet, he would emerge from his cell, talk to the monks and admonish them. To those who ask for subjects of Meditation, he would give them according to their temperament.

He would then retire to his cell and, if he so desire, sleep for a while.

After that, he looks around the world with his divine eye, seeking whom he may serve, and would then preach to those who come to him for instruction.

In the evening he would bathe, and then, during the first watch, attend to monks seeking his advice. The middle watch is spent with devas and others who visit him to question him.

The last watch is divided into three parts: the first part is spent in walking about for exercise and Meditation; the second is devoted to sleep; and the third to contemplation, during which those who are capable of benefiting by The Buddha's teaching, through good deeds done by them in the past, come into his vision. Only beings that are veneyyā (capable of benefiting by instruction) and who possess upanissaya, appear before The Buddha's divine eye (DA.ii.470).

The Buddha gives his visitors permission to ask what they will. This is called Sabbaññupavārana, and only a Buddha is capable of holding to this promise to answer any question (SNA.i.229).

Except during the rains, The Buddha spends his time in wandering from place to place, gladdening men and inciting them to lead the good Life.

This wandering is called cārikā and is of two kinds - turita and aturita.

The first is used for a long journey accomplished by him in a very short time, for the benefit of some particular person.

Thus Gotama travelled three gāvutas to meet Mahā Kassapa, thirty yojanas to see Alavaka and Angulimāla, forty five yojanas to see Pukusāti, etc. In the case of aturita cārikā progress is slow.

The range of a Buddha's cārikā varies from year to year. Sometimes he would tour the Mahā Mandala of nine hundred yojanas, sometimes the Majjhimamandala of nine hundred yojanas, sometimes only the Antomandala of six hundred yojanas.

A tour of the Mahā Mandala occupies nine months, that of the Majjhimamandala eight, and that of the Antomandala from one to four months. Details of the cārikā and the reasons for them are given at length in DA.i.240 3.

When The Buddha cannot go on a journey himself, he sends his chief disciples (SNA.ii.474). The Buddha announces his intention of undertaking a journey two weeks before he starts, so that the monks may get ready (DhA.ii.167).

The Buddha is omniscient, not in the sense that he knows everything, but that he could know anything should he so desire (see MNid.178,179; see also MNidA.223; SNA.i.18.).

His ñāña is one of the four illimitables (neither can The Buddha's Body be measured for purposes of comparison with other bodies, MA.ii.790). He converts people in one of three ways:

- by exhibition of miraculous powers (iddhipātihāriya),

- by reading their thoughts (ādesanāpātihāriya),

- or teaching them what is beneficial to them according to their character and temperament (anusāsanīpātihāriya).

It is the last method, which The Buddha most often uses (BuA.81) The Buddha's rivals say that he possesses the Power of fascination (āvattanīmāyā);

but this is untrue, as sometimes (e.g., in the case of the Kosambi monks) he cannot make even his own disciples obey him. Some beings, however, can be converted only by a Buddha.

They are called buddha veneyyā (SNA.i.331).

Some are pleased by The Buddha's looks, others by his voice and words, yet others by his austerities, such as the wearing of simple robes, etc.; and finally, those whose standard of judgment is goodness, reflect that he is without a peer (DhA.iii.113f.).

Though The Buddha's teaching is never really lost on the listener, he sometimes preaches knowing that it will be of no immediate benefit (see, e.g., Udumbarikasīhanāda Sutta, D.iii.57).

It is said that wherever a Monk dwells during The Buddha's time, in the vicinity of The Buddha, he would always have ready a special seat for The Buddha because it is possible that The Buddha would pay him a special visit (DA.i.48).

Sometimes The Buddha will send a ray of Light from his Gandhakuti to encourage a Monk engaged in Meditation and, appearing before him in this ray of Light, preach to him. Stanzas so preached are called obhāsagāthā (SNA.i.16, 265).

Every Buddha founds an Order; the first pātimokkhuddesagāthā of every Buddha is the same (DA.ii.479). The attainment of arahantship is always the aim of The Buddha's instruction (DA.iii.732).

Beings can obtain the four abhiññā only during the lifetime of a Buddha (AA.i.204). A Buddha has ten powers (balāni) which consist of his perfect comprehension in ten fields of Knowledge,

A.v.32f.; M.i.69, etc. At S.ii.27f., ten similar powers are given as consisting of his Knowledge of the Paticasamuppāda.

The powers of a disciple are distinct from those of a Buddha (Kvu.228); they are seven (see, e.g., D.iii.283) and physical strength equal to that of one hundred thousand crores of Elephants (BuA.37).

He alone can digest the Food of the devas or Food which contains the ojā put into it by the devas. No one else can eat with impunity the Food which has been set apart for The Buddha (SNA.i.154).

Besides these excellences, a Buddha possesses the four assurances (vesārajjāni, given at M.i.71f)), the eighteen āvenikadhammā*, and the sixteen anuttariyas**.

- *Described at Lal. 183, 343, Buddhaghosa also gives (at DA.iii.994) a list of eighteen buddhadhammā, but they are all concerned with the absence of duccarita in the case of The Buddha.

- **Given by Sāriputta in the Sampasādāniya Sutta (D.iii.102ff.).

The remembrance of former births a Buddha shares with six classes of purified beings, only in a higher degree.

This faculty is possessed in ascending scale by

- titthiyā,

- pakatisāvakā,

- mahāsāvakā,

- aggasāvakā,

- pacceka buddhā and

- buddhā (E.g.,Vsm.411).

Every Buddha holds a Mahā Samaya, and only a Buddha is capable of preaching a series of suttas to suit the different temperaments of the mighty assembly gathered there (D.ii.255; DA.ii.682f).

A Buddha is not completely immune from disease (e.g., Gotama).

Every Buddha has the Power of living for one whole kappa," but no Buddha does so, his term of Life being shortened by reason of climate and the Food he takes (DA.ii.413).

The Commentary explains (DA.ii.554f.) that kappa here means āyukappa, the full span of a man's Life during that particular age.

Some, like Mahāsīva Thera, maintained that if The Buddha could live for ten months, overcoming the pains of Death, he could as well continue to live to the end of this Bhaddakappa.

But a Buddha does not do so because he wishes to die before his Body is overcome by the infirmities of old age.

No Buddha, however, dies till the Sāsana is firmly established (D.iii.122).

There are three parinibbānā in the case of a Buddha:

The first takes place under the Bodhi tree, the second at the moment of The Buddha's Death, the third long after (DA.iii.899f.; for the history of Gotama's relics see Gotama).

Some Buddhas live longer than others; those that are dighāyuka have only sammukhasāvakā (disciples who hear the Doctrine from The Buddha himself), and at their Death their relics are not scattered, only a single thūpa being erected over them (SNA. 194, 195).

Short lived Buddhas hold the uposatha once a fortnight; others (e.g. Kassapa Buddha) may have it once in six months; yet others (e.g. Vipassī) only once in six years (ThagA.i.62).

After The Buddha's Death, his Doctrine is gradually forgotten.

The first Pitaka to be lost is the Abhidhamma, beginning with the Patthāna and ending with the Dhammasangani.

Then, the Anguttara Nikāya of the Sutta Pitaka, from the eleventh to the first Nipāta; next the Samyutta Nikāya from the Cakkapeyyāla to the Oghatarana;

then the Majjhima, from the Indriyabhāvanā Sutta to the Mūlapariyāya Sutta, and then the Dīgha, from the Dasuttara to the Brahmajāla. Scattered gāthā like the Sabhiyapucchā, and the ālavakapucchā, last much longer, but they cannot maintain the Sāsana.

The last Pitaka to disappear is the Vinaya, the last portion being the mātikā of the Ubhatovibhanga (VibhA.432).

When a Buddha dies, his Body receives the honours due to a monarch (these are detailed at D.ii.141f).

It is said that on the night on which a Buddha attains Enlightenment, and on the night during which he dies, the colour of his skin becomes exceedingly bright (D.ii.134).

Here we have the beginning of a legend which later grew into an account of an actual "transfiguration" of The Buddha.

At all times, where a Buddha is present, no other Light can shine (SNA.ii.525).

No Buddha is born during the samvattamānakappa, but only during the vivattamānakappa (SNA.i.51).

A Bodhisatta who excels in paññā can attain Buddhahood in four asankheyyas; one who exels in saddhā, in eight, and one whose Viriya is the chief factor, in sixteen (SNA.i.47f).

When once a being has become a Bodhisatta there are eighteen conditions from which he is immune (SNA.i.50). The Buddha is referred to under various epithets.

The Anguttara Nikāya gives one such list. There he is called Samana, Brāhmana, Vedagū, Bhisaka, Nimmala, Vimala, Ñānī and Vimutta (C.iv. 340). Buddhaghosa gives seven others: Cakkkumā, Sabbabhūtanukampī, Vihātaka, Mārasenappamaddī, Vusitavā, Vimutto and Angirasa (DA.iii.962f).

The Buddha generally speaks of himself as Tathāgata.

This term is explained at great length in the Commentaries - e.g., DA.i.59f. His followers usually address him as Bhagavā, while others call him by his name (Gotama).

In the case of Gotama Buddha, we find him also addressed as Sakka (SN. vs. 345; perhaps the equivalent of Sākya), Brahma (SN. p.91; SNA.ii.418), Mahāmuni (BuA.38) and Yakkha (M.i.386; also KS.i.262).

Countless other epithets occur in the Books, especially in the later ones.

One very famous formula, used by Buddhists in their ritual, contains nine epithets, the formula being:

(these words are analysed and discussed in Vsm. 198 ff).

It is maintained (e.g., DA.i.288) that The Buddha's praises are limitless (aparimāna). One of his most striking characteristics, mentioned over and over again, is his Love of quiet.

E.g., D.i.178f.; he is also fond of solitude (patissallāna), (D.ii.70; A.iv.438f.; S.v.320f., etc.). When he is in retirement it is usually akāla for visiting him (D.ii.270).

There are also certain accusations, which are brought against a Buddha by his rivals, for this very Love of solitude. "It is said that his insight is ruined by this habit of seclusion.

By intercourse with whom does he attain lucidity in Wisdom? He is not at his ease in conducting an assembly, not ready in conversation, he is occupied only with the fringe of things. He is like a one eyed cow, walking in a circle" (D.iii.38).

In this his disciples followed his example (D.iii.37). The dwelling place of a Buddha is called Gandhakuti. His footprint is called Padacetiya, and this can be seen only when he so desires it.

When once he wishes it to be visible, no one can erase it. He can also so will that only one particular person shall see it (DhA.iii.194).

It is also said that his Power of Love is so great that no Evil action can show its results in his presence (SNA.ii.475).

A Buddha never asks for praise, but if his praises are uttered in his presence he takes no offence (ThagA.ii.42).

When The Buddha is seated in some spot, none has the Power of going through the air above him (SNA.i.222). He prefers to accept the invitations of poor men to a meal (DhA.ii.135).

2. Buddha. A king of forty one kappas ago, a previous birth of Vacchapāla (Pāyāsadāyaka) Thera. ThagA.i.160; Ap.i.157.

3. Buddha. A minister of Mahinda V.

He was a native of Māragallaka and, in association with Kitti, another minister, vanquished the Cola army at Palutthagiri.

He received as reward his native village. Cv.lv.26 31.

4. Buddha. A Kesadhātu, general of Parakkamabāhu I. He inflicted a severe defeat on Mānābharana at Pūnagāmatittha. Cv.lxxii.7.

5. Buddha. See Buddhanāyaka.

Source

buddha. (T. sangs rgyas; C. fo; J. butsu/hotoke; K. pul 佛). In Sanskrit and Pāli, “awakened one” or “enlightened one”; an epithet derived from the Sanskrit root √budh, meaning “to awaken”

or “to open up” (as does a flower) and thus traditionally etymologized as one who has awakened from the deep sleep of ignorance and opened his consciousness to encompass all objects of knowledge.

The term was used in ancient India by a number of different religious groups, but came to be most strongly associated with followers of the teacher Gautama, the “Sage of the Śākya Clan” (Śākyamuni), who claimed to be only the most recent of a succession of buddhas who had appeared in the world over many eons of time (Kalpa).

In addition to Śākyamuni, there are many other buddhas named in Buddhist literature, from various lists of buddhas of the past, present, and future, to “buddhas of the ten directions” (daśadigbuddha), viz., everywhere.

Although the precise nature of buddhahood is debated by the various schools, a buddha is a person who, in the far distant past, made a previous vow (Pūrvapraṇidhāna) to become a buddha in order to reestablish the dispensation or teaching (Śāsana) at a time when it was lost to the world.

The path to buddhahood is much longer than that of the Arhat—as many as three incalculable eons of time (Asaṃkhyeyakalpa) in some computations— because of the long process of training over the Bodhisattva path (Mārga), involving mastery of the six or ten “perfections” (Pāramitā).

Buddhas can remember both their past lives and the past lives of all sentient beings, and relate events from those past lives in the Jātaka and Avadāna literature.

Although there is great interest in the West in the “biography” of Gautama or Śākyamuni Buddha, the early tradition seemed intent on demonstrating his similarity to the buddhas of the past rather than his uniqueness.

Such a concern was motivated in part by the need to demonstrate that what the Buddha taught was not the innovation of an individual, but rather the rediscovery of a timeless truth (what the Buddha himself called “an ancient path” S. purāṇamārga, P. purāṇamagga)) that had been discovered in precisely the same way,

since time immemorial, by a person who undertook the same type of extended preparation.

In this sense, the doctrine of the existence of past buddhas allowed the early Buddhist community to claim an authority similar to that of the Vedas of their Hindu rivals and of the Jaina tradition of previous tīrthaṅkaras.

Thus, in their biographies, all of the buddhas of the past and future are portrayed as doing many of the same things.

They all sit cross-legged in their mother’s womb; they are all born in the “middle country” (madhyadeśa) of the continent of Jambudvīpa;

immediately after their birth they all take seven steps to the north; they all renounce the world after seeing the four sights (Caturnimitta; an old man, a sick man, a dead man, and a mendicant) and after the birth of a son;

they all achieve enlightenment seated on a bed of grass; they stride first with their right foot when they walk; they never stoop to pass through a door; they all establish a Saṃgha;

they all can live for an eon if requested to do so; they never die before their teaching is complete; they all die after eating meat.

Four sites on the earth are identical for all buddhas: the place of enlightenment, the place of the first sermon that “turns the wheel of the dharma” (Dharmacakrapravartana), the place of descending from Trāyastriṃśa (heaven of the thirty-three), and the place of their bed in Jetavana monastery.

Buddhas can differ from each other in only eight ways: life span, height, caste (either brāhmaṇa or Kṣatriya), the conveyance by which they go forth from the world, the period of time spent in the practice of asceticism prior to their enlightenment, the kind of tree they sit under on the night of their enlightenment, the size of their seat there, and the extent of their aura.

In addition, there are twelve deeds that all buddhas (dvādaśabuddhakārya) perform.

(1) They descend from Tuṣita heaven for their final birth; (2) they enter their mother’s womb; (3) they take birth in Lumbinī Garden; (4) they are proficient in the worldly arts; (5) they enjoy the company of consorts; (6) they renounce the world; (7) they practice asceticism on the banks of the Nairañjanā River; (8) they go to the Bodhimaṇḍa; (9) they subjugate Māra; (10) they attain enlightenment; (11) they turn the wheel of the dharma; and (12) they pass into Parinirvāṇa.

They all have a body adorned with the thirty-two major marks (Lakṣaṇa; Mahāpuruṣalakṣaṇa) and the eighty secondary marks (Anuvyañjana) of a great man (Mahāpuruṣa).

They all have two bodies: a physical body (Rūpakāya) and a body of qualities (Dharmakāya;

see Buddhakāya).

These qualities of a buddha are accepted by the major schools of Buddhism.

It is not the case, as is sometimes suggested, that the buddha of the mainstream traditions is somehow more “human” and the buddha in the Mahāyāna somehow more “superhuman”;

all Buddhist traditions relate stories of buddhas performing miraculous feats, such as the Śrāvastī Miracles described in mainstream materials.

Among the many extraordinary powers of the buddhas are a list of “unshared factors” (Āveṇika(Buddha)dharma) that are unique to them, including their perfect mindfulness and their inability ever to make a mistake.

The buddhas have ten powers specific to them that derive from their unique range of knowledge (for the list, see Bala).

The buddhas also are claimed to have an uncanny ability to apply “skill in means” (Upāyakauśalya), that is, to adapt their teachings to the specific needs of their audience.

This teaching role is what distinguishes a “complete and perfect buddha” (Samyaksaṃbuddha) from a “solitary buddha” (Pratyekabuddha) who does not teach:

a solitary buddha may be enlightened but he neglects to develop the great compassion (Mahākaruṇā) that ultimately prompts a samyaksaṃbuddha to seek to lead others to liberation.

The Mahāyāna develops an innovative perspective on the person of a buddha, which it conceived as having three bodies (Trikāya):

the Dharmakāya, a transcendent principle that is sometimes translated as “truth body”; an enjoyment body (Saṃbhogakāya) that is visible only to advanced bodhisattvas in exalted realms; and an emanation body (Nirmāṇakāya) that displays the deeds of a buddha to the world.

Also in the Mahāyāna is the notion of a universe filled with innumerable buddha-fields (Buddhakṣetra), the most famous of these being Sukhāvatī of Amitābha.

Whereas the mainstream traditions claim that the profundity of a buddha is so great that a single universe can only sustain one buddha at any one time,

Mahāyāna Sūtras often include scenes of multiple buddhas appearing together. See also names of specific buddhas, including Akṣobhya, Amitābha, Amoghasiddhi, Ratnasambhava, Vairocana.

For indigenous language terms for buddha, see Fo (C); Hotoke (J); Phra Phuttha Jao (Thai); Puch’ŏ(Nim) (K); Sangs Rgyas (T).

Source

The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism by Robert E. Buswell Jr. and Donald S. Lopez Jr.