A Discussion of the Views of Different Schools in Tibet, in Chronological Order - The First Phase of Madhyamika

Abstract of: "A discussion of the views of different schools in Tibet, in chronological order".

1. Eighth century views. particularly those of Shantarakshita, (zhi ba 'tsho) and KamalazIla, who were invited to Tibet from India. Kamalishila's debate with Chinese Buddhist scholars .

2. The view and meditational practices of Lha blama yeshe 'od, Lo tsa ba Rinchen Sangpo, Zhiba 'o, Jangchub 'o, Marpa Lotsa, and 'Gos Khugpa lhas btsas in the 11th century.

In this period Tantric practices, often misunderstood, acquired a leading position in Tibetan people's beliefs.

3. The view and meditational practices of Saskya Kun dga' ragayl mtsan, Me ston shes rab 'od zer,(bon) 'Drigung 'Jig rten mgon po, in the 12th. century, and Bu ston rinchen grub, 'Gro mgon Blo gros rgyal mtsan, Bru Rgal ba gyung drung,(bon) in the 13th.

In particular whether they thought Sutra and Tantra are compatible, and whether the view that they are, was widely accepted.

4. The view and meditational practices of Jonang pa, Nya dbon Kun dga' dpal, rje Red mda' ba, rje Tsong kha pa, bodong Phyogs las rnam rgayal, rong stson Shakya rgyal mtsan, nyam med Sherab rgyal mtsan, rmeu Mkhas pa dpal chen, (bon) go bo Bsod nams senge, Shakya mchog ldan and stag lo shes rab

rinchen in the 14th and 15th century, when the view that Sutra and Tantra are compatible became predominant , and Dharma teaching, debating and writing were widespread.

5. The views discussed above are classified as Dzog-Chen, Mahamudra, and Madhyamika. Their respective positions on relative ver. absolute truth are compared.

How the view, meditational, and other practices of Yundrung Bon developed throughout the periods discussed above, and how its views of Sutra and Tantra differ from those of Tibetan Buddhism

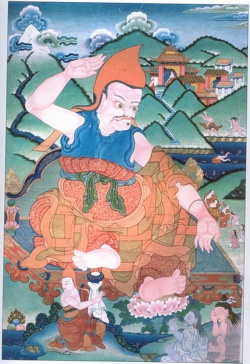

Bod kyi mdos glud la dpyad pa’I gtam skya reng gsar pa

(Offerings to mountain spirits)

Khalong Dochen, the oldest written documents, has been considered by many as the standard work and probably the best source of researching Tibetan tradition of offering mountain spirits.

This study is primarily been classified into three main sections:

First, it covers up the definition of offering mountain spirit which includes procedures, results and origin of offering the mountain spirits.

Second, it describes the 5 terms of the contents of Khalong and those are

1.How and when did evolution of Khalong take place?

2. Profound teaching of knowledge on offering the mountain spirits.

3. Information on origin, nature and benefits of Sidpe Chokrab and also on characteristics of Ngarglud.

4. Independent discussion on origin and nature of the most important part; Sipe Gyalmo.

5. Summarization of entire course.

Third, a comparative study on the artistic characteristics of Khalong and Dunhuang documents.

The Garuda Wingsa

Collected Works in Tibetan Studies

This book was published by Vajra Publications, Kathmandu, Nepal in 2009 and the book is a result of long research on Tibetan religion and its’ culture. It is alienated into four parts.

1. Notes on the urgent need for honest research into some polemical writings about the Bon religion.

Abstract of “The Essential Meanings of Yungdrung Bon Tantric Teachings”

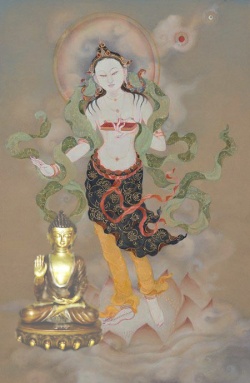

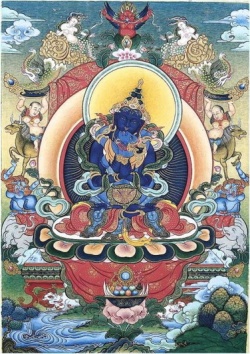

This article discusses the history of the tantric teachings of the Bon religion, from their emergence in the gods' realm and transmission to the human realm, to their rises and falls in Shang Shung and Tibet.

The transmission of the teachings began with The Three Kayas (sku gsum), was passed onto The Yum-sray-gshen-gsum triad of gods, then to The Six Great Lamas (bla ma che drug}, The Thirteen Lineage Holders (gdung rgyud bchu gsum), The [[Four[Scholarly Masters]] (mkhas pa mi bzhi), and then to Drenpa Namkha (dren pa nam mkha). It is argued that, contrary to the widely accepted view, the Bon tantric teachings were already established before Tonpa Shenrab.

In the Eighth Century, following the conversion of the Tibetan king, Trisong Detsan, to Buddhism, the Bon religion was suppressed. In the Eleventh Century there was a revival: many ancient manuscripts were rediscovered, mainly by treasure-revealer Shen Luga(gshen klu dg'). From that period on, the tantric teachings of Bon have been practiced continuously. The locations of the sites where the tantric masters and lineage holders practiced are identified and illustrated with photos. Finally, it is argued that there is no incompatibility between sutra and tantra in Bon religion.

It is said that many textual traditions of Madhyamika were translated by three translators- Ka, Cog, Zhang in the early dissemination of Buddha teachings. In the 8th century, many works were written leading to the establishment of the tradition of Madhyamika teaching and learning, such as, “Series of Quintessential Instructions on View” said to be written by Pema Sambawa, “Talking about Stages of View” by Ka Ba dPal bTsegs, “the Definite Meaning of Madhyamika” by kLu yi rGyal mTshan,

“The Difference of Views” by Zhang Ye Shes sDe, “The Ornament for the Middle Way” by Shantarakshita, “Three Stages of Meditation” and “Illumination of the Middle Way” by Ka Ma La Shi La. Abbot Shantarakshita and Ka Ma La Shi La are said to establish schools for Madhyamika study.

This period witnessed the first debate with the very learned Chinese Buddhist monk Ha Shang. At reading the Special Insight and Analytical Meditation in the text of “The Explanation on the Absolute Meaning”, the learned Chinese Buddhist monk so strongly disagreed that he stepped on the text and criticized that how these views were possible to belong to the great vehicle.

At that time, there was hot debate over views between instantaneous(sTon Min) and gradual (rTsen Min)enlightenment. It seemed that prince Khri Srong De Tsen favored the view of gradual enlightenment, and disagreed with the other.

Many followers of the view of instantaneous enlightenment jumped off the cliff and committed suicide to express their protest. Finally it was decided to invite Ka Ma La Shi La to debate with the learned Chinese Buddhist monk Hashang. At the end, the latter failed and was expelled to the Dunhuang direction.

It is certain that the refutation was not just directed to Chinese Buddhist view as not doing anything with mind, but was mainly towards his view on activity. “However inside the book-‘Stages of Meditation’ there were not many details about this” said aBrug Pa Pad dKar.

Lopon Kamalashila mentioned that the successive meditation stages set as initial, middle and final in the book were very significant. And this book has been written down mainly by the order of the king.

At that period, the subdivision of view into the Prasangika (Thal aGyur Ba) and the Svatantrika (Rang rGyud pa) was not yet popular. Abbot Shantarakshita and Kamalashila were said to take the view of Yogic Autonomy Madhyamika School.

Among the current Kanjur (The Translated Words of Buddha) of Yungdrung Bon, the dominant contents are about Vinaya, Abhidharma and Sutra taught by Buddha Tonpa Sherab.

Therefore, Madhyamika had been widely established. Nowadays it is difficult to recognize the scale for the teaching and learning of Madhyamika during the 1st Bonpo missionary period.

(As is written in the text “Compassionate Mother Tantra”(Byams Mai rGyud)- during the rule of king sTag Ri gNyan gZigs and others, there emerged countless well learned masters on texts such as, Extensive Hundred Thousand Vast Teachings, Six Transmissions of Vinaya, Four Sections of Abhidharma, and Five Classes of Dialectics.)At that time in Bon, the text on Successive Grades of the Spiritual Path Theg Rim translated by Lo chen Be Ro Tsa Na was the most detailed in presentation.

It is assumed that at that time in Tibet teaching and learning Madhyamika haven’t become widespread yet.

During the rule of the Tibetan kings, most of the time there were only small gatherings of secret Tantric practitioners.

Other than that, there was no evidence of the great popularity of big schools for Madhyamika teaching and learning.

It is difficult to differentiate between Bon and Nyingma regarding their Theg Rim’s philosophical systems, views and activities.

It is strange that some indisputable experts of Bon such as Tshul Khrims dPal Chen, didn’t show their interest in Theg Rim texts.

According to Bonpo history, a lot of Kanjur were hidden during the rule of king Gri Gum bTsanpo (710AD). Among them there were many Bonpo Khams Chen and Paramitra (Sher Phyin) texts which were not able to be discovered until the latter of the 10th century.

For this reason, it was possible there was no chance for the study of these texts during that time.

Later in the 10th century, in the southern and northern areas a lot of profound Madhyamika texts- ‘Bum (One Hundred Thousand Verses) in extensive, middle and short versions were revealed.

The main subjects of these texts were in accordance with Buddhist Yum texts of Indian origin in extensive, middle and short versions.

At the same time of the 2nd missionary period of Buddhist teaching in Tibet, teaching and learning Bonpo doctrines in general and in particular profound Madhyamika were able to develop to some degree, but a wide base hasn’t been able to form even today.

The Second Phase of Madhyamika

In the 11th century, Saint Atisha came to Tibet.

He wrote commentaries about Madhyamika such as “Entering into Two Truths” and “the Instruction of Madhyamika” and etc.

From this time on, Madhyamika teaching and learning grew. According to the general history of the Buddha’s teachings in Tibet, in the early period, there emerged many mistaken views about Tantra and religion in general, which Lha Lama Ye Shes ‘od and Zhi Ba ‘Od and etc. have criticized about.

Besides, Sutra and Tantra were viewed as opposite as water to fire and was widely refuted by countless scholars.

In Bonpo, in the Theg Rim texts there were so many main texts explaining successions of view and realization.

From these texts we can say there existed the clear view of the contradictory position between Sutra and Tantra.

During the same period, Marpa chokyi lodo,(1012-1097) the translator, went to India to study religion. He studied Madhyamika texts with Naropa and Me Tri Pa. aGos Khug Pa lHas bTsas translated Madhyamika texts. Ra Lo Tsa Ba was said to study Madhyamika from Lopon Rig Pi Khu Byug.

At the later part of the 11th century, Pa Tshab Lo Tsa Ba (1045-)translated into Tibetan “the Root Commentary on aJug Pa” and “Commentary on the 400 Verses” and etc. written by venerable Chandrakirti (zLa ba grags Pa).

After that the teaching and learning of the Prasangika (Thal ‘Gyur Ba) and the Svatantrika (Rang rGyud Pa) of Madhyamika became flourished.

His disciples known as Pa Tshab’s Four Sons together with others developed the teaching and learning of the Prasangika (Thal ‘Gyur Ba) texts.

Shortly after Pa Tshab, Lopon Dza Ya Ananta from the Kashmir area came to Tibet, and translated Madhyamika texts and developed relevant studies(with his disciple Khu mDo sDe aBar composed “Explanatory Commentaries about Entering into Madhyamika” and “Hammer of Madhyamika Dialecticians” etc.).

Nyingmapa scholar Rong Zom Chos bSang (1040-1159) who emerged during this period was said to support the Madhyamika view of the Prasangika (Thal ‘Gyur Ba). But we need to check the authenticity of this.

At the same period, Bonpo scholar Tsul Khrims dPal Chen appeared (1052-?).

He studied not only Bon but also entered the Buddhist debate school.

He studied hard texts written by Indian scholars and his wisdom was greatly triggered by these philosophical logics so that he could write

“Stages of Clear Realization of Bon” and “Eight Chapters of Commentaries on Khams” which gave brilliant explanations on the sixteen volumes of Khams Chen taught by Tonpa Shenrab.

Not only that, he established a new tradition which had not been done by any scholars before.

Lopon Cha Pa Chos kyi Seng ge(1099-1169) set up the three eastern Svatantrikas (Rang rGyud Pa).

He was said to raise extensive refutation against Chandrakirti in his book “Essential Exposition on Madhyamika”.

In Bon, in the 11th century, Me sTon Shes Rab ‘od Zer(1058-1132) wrote five main texts named as “The Five Sections of Teachings and Commentaries”.

Especially he wrote “The Presentation of Stages of the Path in Three Hundred Verses” which popularized the method of practice in the meditational stages in Sutra. It could be said that ever since then, the way of compatible unity of Sutra and Tantra began.

(As there is no extensive biography of Me sTon Shes Rab ‘od Zer, it is difficult to present his history in details.

In his book “Self Commentary of Madhyamika”, quotations were cited from another book- “Entering into Madhyamika”).

In 13th century, Madhyamika books such as “Illumination of Shakyamuni’s Contemplation” and “Profound Explanations on Authoritative Texts” written by Sa sKya Pandita Kun dGa rGyal mTshan (1182-1251)and others like “Differentiating the Three Precepts ” were written.

These three main texts can be considered to clarify the meaning of Madhyamika.

In the upper part of the 14th century, based on texts about Buddha essence, [[Jo [Nang Kun mKhyen Shes Rab rGyal mTshan]](1292-1361) explained about Madhyamika views as emptiness of other, independent existence, everlasting, true existence, which laid a new tradition.

In Sa sKya sect, dPang bLo Gros brTan Pa(1276-1342) and gYag sDe Pan Chen(1299-1378) and etc. also contributed to the development of Madhyamika teaching and learning.

The Third Phase of Madhyamika

It was from the 14 century that the teaching and learning of the logic system of Madhyamika scriptural tradition became more and more popular.

During this time in Tibet there appeared many excellent scholars at texts in general and Madhyamika in particular.

These great scholars often debated with each other, which was a wonderful display of intellectual reasoning.

During the same period, Rong sTon Shaky rGyal mTshan (1367-1449) and Bo Dong Phyogs Las rNam rGyal,(1375-1451) Nya dBon Kun dGa dPal (1345-1439)and rJe bTsun Red aDa Ba(1349-1412) and their disciple the great venerable rJe Tsong Kha Pa (1357-1419)and his heart disciple Chos rJe these two people(rgyal tsab and khedrub)and some others made the teaching and learning of profound Madhyamika and qualified teaching and practice very much developed.

Because of that from that time till now, varieties of Dharma lineages in Tibet remain undeclined.

Rong sTon Shakya rGyal mTshan’s close disciple, an expert of Bon religion, mNyam Med Shes Rab rGyal Tshan(1356-1415) wrote excellent commentaries about the authoritative texts written by Me sTon Shes Rab ‘od Zer, focusing on their essence.

At this time in Tibet, the custom of unity of Sutra and Tantra was sprouting.

Accordingly, for Bon, with the base of the earlier establishment of this custom, at this period, it became more stabilized.

The path of the unity of Sutra and Tantra became largely widened.

Different Viewpoints in Tibet

The great teacher Shantarakshita and his disciples, were known as the main holders of yogachara-the Svatantrika.

rNgog bLo lDan Shes Rab (1059-1109)and Cha Pa Chos Seng took the three eastern Svatantrikas as their main views.

Pa Tshab and his followers held Chandrakirti‘s prasangika perfectly.

kLong Chen Rab aByams Pa(1308-1363) regarded the Prasangika as the highest view of Madhyamika.

Marpa Lo Tsa Ba, Milarepa and Gampopa (Dags po lha rje bSod Nams Rin Chen 1079-1153)were mainly engaged in practicing Mahamudra.

Although there were not any commentary and clarification concerning Madhyamika written by them, the evidence that venerable Me Tri Pa was the follower of Chandrakirti, concludes that they are also followers of the Prasangika-madhyamika, said by some scholars.

In the 14th century, Karmapa Rang aByung rDor rJe (1284-1339) was the follower of emptiness of other.

As the 7th Karmapa Chos Grags rGya mTsho,(1454-1506) the 8th Karmapa Mi bsKyod rDo rJe (1507-1554)and the 9th Karmapa dBang Phyug rDo rJe (1556-1603)were all the followers of emptiness of other, many other Kagyu Pa after them accepted the same view as well.

Sakya Pandita studied “Six Scriptures on Reasoning of the Madhyamika”.

Judging from the two books written by him “Illumination of Shakyamuni’s Contemplation” and “Clear Explanations about the Authoritative Texts”, we can say that he is the follower of Chandrakirti.

Rong sTon Shakya rGyal mTsan was known as the follower of Svantantra-madhyamika.

Shakya mChog lDen first followed Cittamatra, then Svantantra, and finally emptiness of other.

He thought it was really different between the views that concluded through cutting superimposition by listening and contemplation and that recognized through meditative experiences.

He referred explanations found in texts- “rDo rJe Gur ” and “Kalachakra” to support his viewpoint.

Emptiness from non-affirming negation in “Six Scriptures on Reasoning” was also necessary to be away from fixation on conceptual attributes.

Some said Go Bo Rab aByams Pa supported Chandrakirti-prasangikas.

In the book “Go Len lta ngan mun sel”(written by Sera rJe-btshun Chos kyi rGyal mTsan), he was said not to belong to either the Prasangika, the Svatantrika or any other Tibetan religious schools before or after the 14th century.

rJe Tsong Kha Pa wrote extensive texts on Madhyamika.

The representative are two big commentaries on the main texts- “Tsa Ba Shes Rab” (Root of Wisdom) and “dBu Ma ‘Jug Pa”

(Entering into the Middle Way), the root texts of which were composed by Nagarjuna and his disciples, mainly Chandrakirti, expressed thoroughly their ideas.

Among Gelug Pa, from the two heart disciples of Tsong Kha Pa to current scholars, they all carried on the Prasangika-Madhyamika view that has been made clear in Tibet by him.

In the 14th century, appeared Jo Nang Shes Rab rGyal mTshan, Bu sTon Rin Chen Grub, Nya dBon Kun dGa dPal, and Bo Dong Phyogs Les rNam rGyal who developed the teaching and learning of Madhyamika.

In the 15th century, appeared sTag Tshang Lo Tsa Ba Shes Rab Rin Chen and etc.

Among these scholars, Dol Po Pa and Nya dBon two were the lineage holders of emptiness-of-other view.

After this, Ta Ra Na Tha was the supporter of emptiness of other.

A major holder of Jonangpa lineage, he spread his views through many books written by him.

Later, apparently bKa rGyud pa and rNying Ma pa scholars like a Ju Mi Pham, Kong sPrul bLo Gros mTha Yas, aJam dByangs mKhyen brTse dBang Po wrote mostly about analysis on Madhyamika views, especially commentaries on emptiness of other, but their commenting style was different from Jonangpa’s.

Three Summed-up Views

To conclude Madhyamika views of scholar-adepts in Tibet discussed above, there are three groups.

First, all existence inner or outer are devoid of a self-nature, or not true, therefore, these truths are merely negated and the perfect nature of all things is emptiness.

Second, the nature of reality is not that these outer and inner truths are merely negated, but also free from having or not having whichever kind of elaborations. It is free from all mental elaborations.

Third, existence of relative truth is emptiness of itself and absolute truth emptiness of other.

This emptiness is the wisdom that bears the quality of emptiness and awareness in inseparable state, which is the absolute nature of reality.

Besides this, Jo Nang Pa asserted that this wisdom is independent, permanent, and truly existent.

First View

Scholar-adepts who support this view are: rNgog bLo lDan Shes Rab, Cha Pa Chos Kyi Seng Ge, Sa Pan Kun dGa gGyal mTshan, aGro mGon bLo Gros rGyal mTshan, rJe Tsong Kha Pa and his followers, Rong sTon Shakya rGyal mTshan, mNyam Med Shes Rab Gyal mTshan, and rMea rGyal mTshan mChog Legs belong to the first view holders.

Second View

[mKhes Pa dPal Chen)], Me sTon Shes Rab Aod Zer, rJe bTsun Red aDa Ba, Bo Dong Phyogs Las rNam rGyal, sTag Tshang Lo Tsa Ba, Go Bo Rab aByams Pa and his followers, and Karmapa Mi bsKyod rDo rJe, Pa Tshab Nyi Ma Grags pa, Zhang Thang Sag Pa Ye Shes aByung gNas, rMa Bya Byang chub brTson agrus, lCe sGom Shes Rab rDo rJe, and gYag Phrug Sangs rGyas dPal hold the view of free from elaboration, mind not doing anything.

Third View

Proponents of this view are Karmapa Rang aByung rDo rJe, Jo Nang Shes Rab rGyal mTshan, Nya dBon Kun dGa dPal, Ta Ra Na Tha, Shakya mChog lDan, aJu Mi Pham pa, aJam dByangs mKhyen mrTsea dBang Po, Kong sPrul Blo gros mtha yas and etc.

Conclusion

Among these three views, the first and second view holders accept the emptiness described by Nagarjuna in “Six Scriptures on Reasoning” and “rTsa ba Shes rab” as the absolute nature of reality.

Emptiness-of-other view holders deny the view in “Six Scriptures on Reasoning” as the absolute nature.

Instead they consider the view described in “bsTod Tshogs”, “Root Text and Commentary of rGyu bLa ma”, and texts on Buddha-nature(bder gshegs snying po’i chos skor) as the absolute truth.

Among Bon, books like Theg aGrel Me Long dGu sKor, Byams Ma aBum lNga, Tshad Ma Gal mDo and Namkha aKhrul mDzod, express Madhyamika view of the reality as emptiness nature through non-existence negation (Med Par dGag Pa).

Based on Khams Chen’s Awareness Khams (Rig pai Khams), Tsul khrims dPal Chen asserted that Madhyamika and Mind series-Tantra and Dzogchen, are same in views.

Based on gZhi Ye Sangs rGyas Pai rGyud of Magyud, there are also explanations of Madhyamika views through non-existence negation.

Till now there haven’t appeared detailed explanations on emptiness of itself and emptiness of other in Bon.

aGro mGon bLo Gros rGyal mTshan and some other people said, among Commentaries on Vehicles, the phrases Rol Pa sKye mChed and mTshan Ma Kun Bral Ba in Bonpo texts are respectively equal in meaning to the Prasangika (Thal aGyur) and the Svatantrika (Rang Gyud) in Buddhist texts.

Although not denying emptiness through non-existent negation, Shakya mChog lDan asserted two subdivisions as Madhyamika of Sutra and Madhyamika of Tantra.

The absolute view is neither the Prasangika (Thal aGyur) nor the Svatantrika (Rang Gyud), but Madhyamika of Tantra.

The opponents of emptiness of itself are found mainly among Jonangpa.

Based on Buddha-nature texts, they argued that the absolute truth is inseparable with base and fruit, everlasting, inherent existent, of and permanent body.

Sakya Pandita and Bu sTon Rinchen Grub both said Buddha-nature texts are taught in relative meanings not following superficial words.

rJe bTsun Red aDa Ba negated emptiness of other as it was not described by Nagarjuna and Asanga either in Chittamatra or Madhyamika divisions.

The great Tsong Kha Pa thought the view of emptiness of other as generally unchanging, ideally absolute and inherent existence was not proper.

He criticized the texts on Buddha-nature should not be understood superficially in words.

His followers also refuted the view of emptiness of other.

sTag Tshang Lo Tsa Ba and Go Rams Pa commented the view of emptiness of other fell into the extreme of permanence, so it was not accepted as Madhyamika view.

Nyingmapa dGe rTse Ba refuted, the Prasangika (Thal aGyur) and the Svatantrika (Rang Gyud) are coarse and classified as outer Madhyamika.

Subtle is as inner Madhyamika appearing when practitioners are in practice.

The view at Buddha’s last turning of the Wheel of dharma, is of absolute reality, which is the great Madhyamika.

This view is very popular among many Tibetan and Indian scholars.

Different terms as secret Tantra, Mahamudra, Dzogchen and Madhyamika of emptiness of other also talk only about this absolute reality, not anything else separately.

This article is an abbreviation of my research on views of different schools in Tibet for the presentation on the Third International Seminar of Young Tibetologists.