Heruka Cakrasamvara

The tradition of meditating on this yidam is based on the Sri Cakrasamvara Tantra. This tantra has been widely studied by all Tibetan schools, and there are many sadhanas and commentaries associated with Cakrasamvara. He is a yidam of particular importance to the [[Kagyu

school]], though as with all the yidams we shall be meeting, devotion to him crosses all sectarian frontiers. His practice is very widespread among the Gelukpas. There is a sadhana known as the Yoga of the Three Purifications of Sri Cakrasamvara' that is quite widely practised at Gelukpa centres in the West.

The first in the line of Cakrasamvara practitioners is generally considered to have been the Indian mahasiddha Saraha. He was a brahmin who had become a Buddhist scholar-monk. However, he was not satisfied by his learning, and set out to find a Tantric teacher. In a market-

place he saw a young low-caste woman making arrows. He became deeply engrossed in watching her working, and finally approached her and asked if she made arrows for a living. She replied, 'My dear young man, the Buddha's meaning can be known through symbols and actions, not through words and books.' Her

arrow hit its mark. Flouting all convention, Saraha went to live with her, receiving her Tantric teachings. As a result, he became one of the greatest of all Tantric adepts. He is particularly renowned for his dohas or songs, in which he expresses the profound realizations he has gained

through Tantric practice. This yidam is known by various names in Sanskrit. Sometimes he is known as Samvara or Sambara, sometimes as Heruka. In Tibetan he is called Khorlo Demchok or Khorlo Dompa. Here we shall refer to him as Cakrasamvara. Though it literally means

'restraint', samvara is associated, by Tibetan lamas explaining the significance of this yidam, with 'supreme bliss'.39 Cakra (now

usually anglicized as chakra) means wheel. It is also the Sanskrit word used for the psychic centres within the body of the meditator, whose manipulation through performing the Cakrasamvara sadhana gives rise to the 'supreme bliss'.

As we have seen, texts of Highest Tantra are often classified into Mother and Father Tantras. Mother Tantras emphasize wisdom - particularly the realization of the indivisibility of bliss and Emptiness. They are particularly suited to those of passionate

temperament, providing methods of liberating the energy tied up in greed and attachment and making it available for the pursuit of

Enlightenment. Cakrasamvara is a central deity of the Mother Tantra class. He can appear in a number of different forms. Here we shall describe just one very well known and characteristic form.

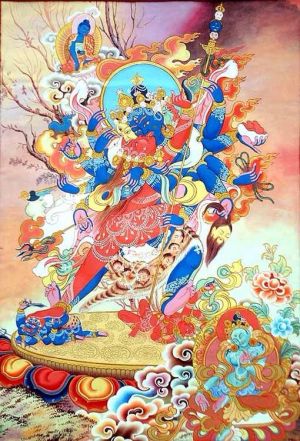

He appears standing on a variegated lotus. Even in this small detail, we see how this world of Highest Tantra differs from the world of the

Mahayana occupied by the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, most of whom were symbolized by one predominant colour. In the world of the yidams we are gazing at an all-encompassing vision, so colours become more varied.

He stands on a sun disc, on which lie two figures being trampled underfoot. One foot pins down the black god Bhairava by the back of the

neck, the other is placed on the breast of the red goddess Kalaratri. Both figures have four arms, two of which hold a curved knife and a skull cup, while the other two are raised in devotion to the great figures above them.

Bhairava and Kalaratri are forms of the god and goddess Shiva and Uma. Shiva is one of the most powerful of all Hindu deities. In later Hinduism he forms one of a triad of gods with Brahma and Vishnu, and is responsible for all the

destructive aspects of the universe. Uma is his consort. In the Vajrayana they are incorporated into the Tantric world-view as minor deities who preside over the desire realm. They are symbolically overcome by Cakrasamvara, and raise their hands in submission to the

transcendental figures that stand over them. Even the highest forms of the mundane appear puny compared to the majesty of this yidam. His body is deep blue, and he has four faces which gaze out into the four cardinal directions. The face that looks directly at us is blue, the one to our right, green, to our left, yellow, and facing away from us, red. All the faces have crowns of skulls. In his hair, to his left, is a crescent moon.

This moon, along with many of the other emblems of Cakrasamvara, is an attribute of Shiva.41 All these Shivaite symbols are given a strictly Buddhist interpretation in the Vajrayana. Here, for instance, the crescent moon symbolizes Bodhicitta which is ever-increasing. Thus

the general suggestion of the figure is of an Enlightened consciousness, having overcome and gone beyond the relatively limited vision represented by Shiva, nonetheless expressing itself through the symbols associated with him. The power of such an image is likely to be largely lost on

Westerners. One would perhaps have to imagine Cakrasamvara trampling underfoot the prostrate form of the God of the Old Testament to gain some idea of its potency in India.

Cakrasamvara has a tiger-skin draped over his loins, and a garland of freshly-severed heads hangs from his neck. He has no less than twelve arms. A central pair embrace his consort Vajravarahi ('diamond sow'). The two hands cross behind her back, holding a vajra and bell in the

vajrahumkara mudra. The right hand with the vajra, and the left with the bell, cross at the wrist, the right arm outermost. His other arms radiate out from his body, forming a rough circle. The right hands, beginning from the top, hold

(I) an elephant hide, which is draped across his back,

(2) a damaru,

(3) an axe,

(4) a chopper with a vajra handle, and

(5) a trident lance.

His left hands, counting downwards, hold

(1) the elephant hide,

(2) a khatvanga, or magic staff (similar to the one we saw Padmasambhava holding),

(3) a skull cup brimming with nectar,

(4) a noose or lasso, and

(5) the severed head of the god Brahma, which has four faces.

He is locked in sexual embrace with his consort Vajravarahi, who by contrast is quite a simple figure. She is brilliant red, with only one face and two arms. Her right hand, raised aloft, holds either a vajra or a flayingknife (Tibetan drigu) with a vajra handle. Her left hand,

embracing her partner's neck, holds a skull cup. She is naked apart from a few bone ornaments, a five-skulled crown, and a [[garland of

skulls]] which hangs from her neck. In some forms both her legs are wrapped around her partner's thighs, in others her right leg is raised while with her left leg she also tramples on Kalaratri. The copulating figures are encircled by an aura of flames.

The symbolism of these figures is so complex, so labyrinthine, that a guru experienced in the Cakrasamvara system could easily produce a large

book on just this one figure. The most important message it conveys is a logic-bemusing union of opposites. Heruka Cakrasamvara and his consort appear from the dimension in which all diversity is unified, and unity displays its endless forms.

The two figures on which the mystic pair drum their feet lie separate.

They represent the realm of mundane experience in which separation is the rule. It is this separation, experienced by most people

as isolation, which fuels desire. Desire urges us to unite, to reach out to overcome separation. But this external seeking gives us at best only temporary relief for our ills. Eventually we lie separate and alone, in the world of me and

you, he and she, good and bad, heaven and hell. Constantly discriminating, reaching out to embrace some experiences and avoiding others, we fail to see that the two parts of all dualities are attached; we cannot grasp one without finding ourselves holding on to the other.

Cakrasamvara and his consort unite all opposites in their sexual embrace. They are really one figure, appearing as two. Their union represents different integrated aspects of one Enlightened consciousness. They exemplify what in Tantra is called yuganaddha - 'two-in-oneness'.

We saw in Chapter One that the female figure, the yum or Mother, is also referred to as the prajna - for she represents wisdom, the intuitive realization of Emptiness. This wisdom sees the common characteristic of all phenomena: everything is devoid of an unchanging,

fixed, self-nature. Everything has the same essential nature, which is 'no-nature'. This wisdom-view applies to everything in the universe. Because nothing has a fixed nature of its own, there are no fixed boundaries or divisions between things. If there are no fixed limits or barriers, if the

seemingly static elements of existence can recombine like the colours of oil on water, then there is no separation. Everything is of one empty nature. Hence the yum has only one face, symbolizing this essential sameness of all things. She is naked to symbolize the simplicity and

unadorned nature of things in their essence. (In Mother Tantras the female consort is always naked, whereas in Father Tantras the consort always wears some item of clothing - usually just a cloth around the loins. This indicates that Mother Tantra is mainly

concerned with the wisdom that sees the essential emptiness of all forms; Father Tantra emphasizes the compassionate expression of wisdom through form.)

In contradistinction to her, the male yab, or Father, represents the compassionate activity of the Enlightened mind - working in the world to awaken beings to their true empty nature. In fact, with his four faces looking into the four directions, and his twelve arms, he

symbolizes the world of appearances, the multiplicity of forms. His partner is the unchanging realization of the emptiness of appearances, the sameness of nature of all forms. Their sexual union suggests the ultimate

nondistinction, on the level of absolute truth, between appearances and Emptiness. Their being two figures suggests that distinctions can still be made on the level of relative truth.

The twelve arms of the male figure represent correct understanding of the twelve links of conditioned co-production (pratitya samutpada). This basic Buddhist teaching is an application of the principle that all things come into existence dependent on particular

conditions, and cease to exist when those conditions change. It applies this general principle to demonstrate the conditions that cause our existence in the circle of samsara, the endless round of unsatisfactory rebirth. These are essentially ignorance of the [[true

nature]] of existence, which causes us to react to pleasant and unpleasant stimuli with desire or aversion. This strengthens

our involvement with these stimuli, which fixes our view of them and embroils us more deeply in the world of impermanence and hence unsatisfactoriness.

In each hand he holds an implement which symbolizes the overcoming of samsara. For example, the elephant hide he holds draped over his back is said to symbolize conquered ignorance, the axe severs the fetters of birth and death, and so on.

Thus the two figures represent a vision of a new universe, which we can enter through contemplating them. In this universe, opposites are united

without losing their distinct validity on the relative level. Dwelling on Cakrasamvara we gain direct intuitive experience of the highest teachings of the Dharma. The opposites of appearances and emptiness, diversity and unity, samsara and nirvana,

compassion and wisdom, discrimination and sameness, relative and absolute, male and female, all fuse in the two

ecstatic figures, and this fusion of opposites causes the dawning of great bliss in the mind of the meditator, a bliss of which sexual union can be only an inadequate cipher.

There are still more opposites that we can find reconciled in this mystic coupling. Wrathfulness and peacefulness are reconciled. It is said of the male figure that while outwardly fierce, he is inwardly compassionate, dignified, and serene.

More important, we find symbols within symbols. On the level of the overall figures, the male Heruka symbolizes skilful means, while his partner stands for wisdom. However, the yah holds in his front two hands the crossed vajra and bell, which themselves represent conjoined

method and wisdom. Again, in the pairing of figures, the yum is receptive, the male active and outgoing. Yet we see that both these attributes

are to be found in the female figure alone. Her left arm and side are passive, and in her left hand she holds the skull cup. Yet her right side is dynamic. With her right leg (in some traditions) she grasps her partner's thigh, and her right hand is thrust upward brandishing aloft the sharp

vajra-chopper, or the dynamic vajra, with her hand in the tarjani mudra of warding off demons. From this we can see that yet another pair

of opposites has fused: macrocosm and microcosm have become one, and the great truths of the Dharma can be seen in the vast and the infinitesimal.

We still have a further step to go before we can grasp even the rudiments of the Cakrasamvara universe. The great yab-yum pair are but the central focus of a vast mandala. There are a number of important Cakrasamvara traditions, passed down from Indian masters, with mandalas

involving different numbers of figures. A common form has sixty-two deities, but some mandalas include several hundred figures altogether. For example, a mandala in the tradition of Maitripada has twelve dakinis, four in an inner circle, and a further eight in an outer ring, of whom

four have animal heads and guard the gates of the mandala. All the dakinis are naked like Vajravarahi. They each have four arms, and these hold a knife, skull drum, skull cup, and trident staff.

To begin to describe a sadhana of Cakrasamvara would take more space than we have available, since the visualizations of yidams of Highest Tantra tend to be long and complex. Anyway, as I have said, of all visualizations these are the ones least put on display to the general

public. I hope our meeting with Cakrasamvara has been long enough to give us some feeling for him, and for us to begin to see why these yidams should be the esoteric Dharma Refuge. A Tantric practitioner in retreat might spend many hours a day in repeated performance of

a Cakrasamvara sadhana. Through recreating him- or herself out of Emptiness in the form of Cakrasamvara united with Vajravarahi, he or she enacts a cosmic drama of the true nature of phenomena. With repeated practice, even when not formally meditating, he or she

experiences the ordinary world of appearances as a mandala in which all opposites are transcended but not obliterated, and dwells in the blissfulness of the two-in-oneness of unity and diversity which is just one of the messages of Cakrasamvara.