Wheel of Life

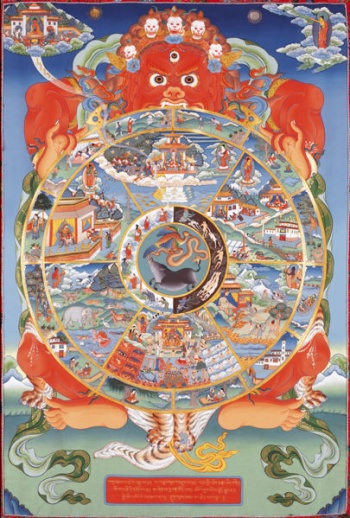

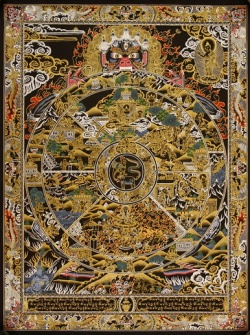

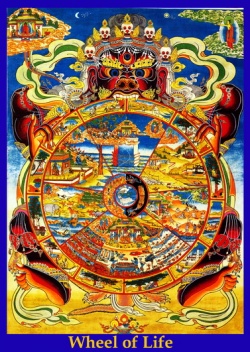

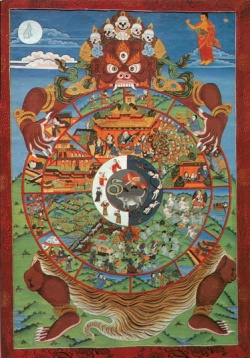

Wheel of Life (Skt. bhavacakra; Tib. སྲིད་པའི་འཁོར་ལོ་, sipé khorlo; Wyl. srid pa'i 'khor lo) — a traditional representation of the samsaric cycle of existence. Also translated as wheel of existence, or wheel of cyclic existence.

Overview

The Wheel of Life is a traditional representation of the samsaric cycle of existence.

Jeffrey Hopkins writes:

- The diagram, said to be designed by Buddha himself, depicts an inner psychological cosmology that has had great influence throughout Asia. It is much like a map of the world or the periodic table of elements, but

it is a map of an internal process and its external effects.[1]

Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche writes:

- It’s quite a popular painting that you can see in front of almost every Buddhist monastery. In fact, some Buddhist scholars believe that the painting existed prior to Buddha’s statues. This is probably the first ever Buddhist symbol that existed...

- One of the reasons why the Wheel of Life was painted outside the monasteries and on the walls (and was really encouraged even by the Buddha himself) is to teach this very profound Buddhist philosophy of life and

perception to more simple-minded farmers or cowherds. So these images on the Wheel of Life are just to

communicate to the general audience.[2]

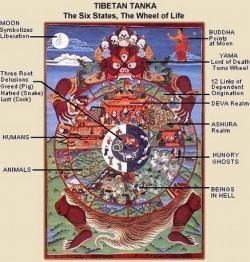

A Brief Explanation of the Diagram

The meanings of the main parts of the diagram are:

- The centre of the wheel represents the three poisons.

- The second layer represents positive and negative actions, or karma.

- The third layer represents the six realms of samsara.

- The fourth layer represents the twelve links of interdependent origination.

- The monster holding the wheel represents impermanence.

- The moon above the wheel represents liberation from the samsaric cycle of existence.

- The Buddha pointing to the moon indicates that liberation is possible.

The Dalai Lama writes:

- Symbolically [the inner] three circles, moving from the centre outward, show that the three afflictive emotions[3] of desire, hatred, and ignorance give rise to

virtuous and non-virtuous actions, which in turn give rise to levels of suffering in cyclic existence. The outer rim symbolizing the twelve links of dependent arising indicates how the sources of suffering—

actions and afflictive emotions—produce lives within cyclic existence. The fierce being holding the wheel symbolizes impermanence...

- The moon [at the top] indicates liberation. The Buddha on the left is pointing to the moon, indicating that liberation that causes one to cross the ocean of suffering of cyclic existence should be actualized.[4]

A Detailed Explanation of the Diagram

Centre of the Wheel: The Three Poisons

Ringu Tulku Rinpoche writes:

- Tibetans have a traditional painting called the Wheel of Life, which depicts the samsaric cycle of existence. In the centre of this wheel are three animals: a pig, a snake, and a bird. They

represent the three poisons. The pig stands for ignorance, although a pig is not necessarily more stupid than other animals. The comparison is based on the Indian concept of a pig being the most foolish

of animals, since it always sleeps in the dirtiest places and eats whatever comes to its mouth. Similarly, the snake is identified with anger because it will be aroused and leap up at the slightest touch. The

bird represents desire and clinging. In Western publications it is frequently referred to as a cock, but this is not exactly accurate. This particular bird does not exist in Western countries, as far as I

know. It is used as a symbol because it is very attached to it's partner. These three animals represent the three main mental poisons, which are the core of the Wheel of Life. Stirred by these, the whole [[cycle of

existence]] evolves. Without them, there is no samsara.[5]

Second Layer: Positive and Negative Actions

The images in this layer vary in different paintings of the wheel. In the image shown here, the two half circles represent positive and negative actions, or karma, that are motivated by the three poisons of ignorance, attachment/desire and aversion/anger.

- The half-circle on the right shows positive or virtuous actions. Such actions are the means for attaining lives in the three higher realms of the gods, demi-gods and humans.

- The half-circle on the left shows negative or non-virtuous actions. Such actions are the means for attaining lives in the three lower realms of the animals, hungry ghosts and hell-beings.

Third Layer: Six Realms of Samsara

The third layer of the wheel depicts the six realms of samsara.

Fourth Layer: Twelve Links

The fourth layer of the wheel depicts the twelve links of interdependent origination.

The Monster Holding the Wheel: Impermanence

Jeffrey Hopkins writes:

- The wheel in the centre of the painting is in the grasp of a frightful monster. This signifies that the entire process of cyclic existence is caught within transience. Everything in our type of life is characterized

by impermanence. Whatever is built will fall down, whatever and whoever come together will fall apart.[6]

The Dalai Lama writes:

- The fierce being holding the wheel symbolizes impermanence, which is why the being is a wrathful monster, though there is no need for it to be drawn with ornaments and so forth... Once I had such a painting drawn with a skeleton

rather than a monster, in order to symbolize impermanence more clearly.[7]

Reflecting on impermanence can start us on the path towards liberation.

Sogyal Rinpoche writes:

- The Western poet Rainer Maria Rilke has said that our deepest fears are like dragons guarding our deepest treasure. The fear that impermanence awakens in us, that nothing is real and nothing lasts, is, we

come to discover, our greatest friend because it drives us to ask: If everything dies and changes, then what is really true? Is there something behind the appearances, something boundless and infinitely spacious, something in

which the dance of change and impermanence takes place? Is there something in fact we can depend on, that does survive what we call death?

- Allowing these questions to occupy us urgently, and reflecting on them, we slowly find ourselves making a profound shift in the way we view everything. With continued contemplation and practice in letting go, we come to uncover in

ourselves "something" we cannot name or describe or conceptualize, "something" that we begin to realize lies behind all

the changes and deaths of the world.[8] Read more

The Buddha and the Moon: Liberation from Suffering

Jeffrey Hopkins writes:

- At the top right of the painting as we face it, the Buddha is standing with his left hand in a teaching pose and with the index finger of the right hand pointing to a moon... The moon symbolizes liberation. Buddha

is pointing out that freedom from pain is possible... The intent of the painting is not to communicate mere

knowledge of a process but to put this knowledge to use in redirecting and uplifting our lives.[9]

Ringu Tulku Rinpoche writes:

- The Buddha showed the gradual way toward the cessation of suffering by means of the Noble Eightfold Path. Again, this is a very basic teaching, yet it is not just a preliminary one. When examined

deeply, it proves to cover the whole journey... The entire teaching of the Buddha is included in this path, which provides the basic guideline on how to work with and overcome the sources of suffering.[10]

Sogyal Rinpoche writes:

- All the spiritual teachers of humanity have told us the same thing, that the purpose of life on earth is to achieve union with our fundamental, enlightened nature... There is only one way to do this, and that

is to undertake the spiritual journey, with all the ardor and intelligence, courage and resolve for transformation that we can muster.[11]

See Also

- Destructive emotions

- Karma

- Six realms

- Twelve links of interdependent origination

- Impermanence

- Rice Seedling Sutra

External Links

Further Reading

- Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, Gentle Voice #22, September 2004 Issue

- Geshe Sonam Rinchen, How Karma Works: The Twelve Links of Dependent Arising, Snow Lion, 2006

- Patrul Rinpoche, The Words of My Perfect Teacher (Boston: Shambhala, Revised edition, 1998), page 96.

- Ringu Tulku, Daring Steps Toward Fearlessness: The Three Vehicles of Tibetan Buddhism, Snow Lion, 2005

- Sogyal Rinpoche, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, Harper San Francisco, 2002

- The Dalai Lama, The Meaning of Life, translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Wisdom, 2000

Footnotes

- ↑ The Dalai Lama, The Meaning of Life, translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Boston: Wisdom, 1992, page 1.

- ↑ Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, Gentle Voice #22, September 2004 Issue, page 3.

- ↑ An alternate translation of the three poisons.

- ↑ The Dalai Lama, The Meaning of Life, translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Boston: Wisdom, 1992, page 42.

- ↑ Ringu Tulku, Daring Steps Toward Fearlessness: The Three Vehicles of Tibetan Buddhism, Snow Lion, 2005 page 30.

- ↑ The Dalai Lama, The Meaning of Life, translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Boston: Wisdom, 1992, page 3.

- ↑ The Dalai Lama, The Meaning of Life, translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Boston: Wisdom, 1992, page 42.

- ↑ Sogyal Rinpoche, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, Harper San Francisco, 2002, page 39.

- ↑ The Dalai Lama, The Meaning of Life, translated and edited by Jeffrey Hopkins, Boston: Wisdom, 1992, page 2.

- ↑ Ringu Tulku, Daring Steps Toward Fearlessness: The Three Vehicles of Tibetan Buddhism, Snow Lion, 2005 page 37.

- ↑ Sogyal Rinpoche, The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, Harper San Francisco, 2002, page 131.

Source

The Wheel of Dependent arising is a basic teaching of Buddhism. The Wheel of Life, with its twelve links starting with ignorance and ending in aging and death, shows how man, being fettered, wanders in Samsara birth after birth.

Upon the Full Moon of the month of Visakha, now more than two thousand five hundred years ago, the religious wanderer known as Gotama, formerly Prince Siddhartha and heir to the throne of the Sakiyan peoples, by his full insight into the Truth called Dharma which is this mind and body, became the One Perfectly Enlightened by himself.

His Enlightenment or Awakening, called Sambodhi, abolished in himself unknowing and craving, destroyed greed, aversion and delusion in his heart, so that "vision arose, super-knowledge arose, Wisdom

arose, discovery arose, light arose - a total penetration into the mind and body, its origin, its cessation and the way to its cessation which was at the same time complete understanding of the "world,"

its origin, its cessation and the way to its cessation. He penetrated to the Truth underlying all existence.

In meditative concentration throughout one night, but after years of striving, from being a seeker, He became "the One-who-Knows, the One-who-Sees."

When He came to explain His great discovery to others, He did so in various ways suited to the understanding of those who listened and suited to help relieve the problems with which they were burdened.

He knew with his Great Wisdom exactly what these were even if his listeners were not aware of them, and out of His Great Compassion taught Dhamma for those who wished to lay down their burdens. The burdens which men,

indeed all beings, carry round with them are no different now from The Buddha's time. For then as now men were burdened with unknowing and craving. They did not know of the Four Noble Truths nor of Dependent arising and

they craved for fire and poison and were then as now, consumed by fears. Lord Buddha, One attained to the Secure has said:

"Profound, Ananda, is this Dependent arising, and it appears profound. It is through not understanding, not penetrating this law that the world resembles a tangled skein of thread, a woven nest of birds, a thicket of

bamboo and reeds, that man does not escape from (birth in) the lower realms of existence, from the states of woe and perdition, and suffers from the round of Rebirth."

The not-understanding of Dependent arising is the root of all sorrows experienced by all beings. It is also the most important of the formulations of Lord Buddha’s Enlightenment. For a Buddhist it is therefore most

necessary to see into the heart of this for oneself. This is done not be reading about it nor by becoming expert in scriptures, nor by speculations upon one’s own and others’ concepts but by seeing

Dependent arising in one’s own life and by coming to grips with it through calm and insight in one’s "own" mind and body.

"He who sees Dependent arising, sees the Dharma."

Represented by an image of a blind woman who blunders forward, unable to see where she is going. So ignorance is blindness, not seeing. It is a lack of insight into the reality of things.

This Pali word "Avijja" is a negative term meaning "not knowing completely" but it does not mean "knowing nothing at all." This kind of unknowing is very special and not concerned with ordinary ways or subjects

of knowledge, for here what one does not know are the Four Noble Truths, one does not see them clearly in one’s own heart and one’s own life. In past lives, we did not care to see 'Dukkha' (1), so we

could not destroy 'the cause of Dukkha' (2) or craving which has impelled us to seek more and more lives, more and more pleasures. 'The cessation of Dukkha' (3) which perhaps could have been seen by us in past

lives, was not realised, so we come to the present existence inevitably burdened with Dukkha. And in the past we can hardly assume that we set our feet upon the 'practice-path leading to the cessation of

Dukkha' (4) and we did not even discover Stream-entry. We are now paying for our own negligence in the past.

And this unknowing is not some kind of first cause in the past, for it dwells in our hearts now. But due to this unknowing, as we shall see, we have set in motion this wheel bringing round old age and death and

all other sorts of Dukkha. Those past "selves" in previous lives who are in the stream of my individual continuity did not check their craving and so could not cut at the root of unknowing. On the

contrary they made Kamma, some of the fruits of which in this present life I, as their causal resultant, am receiving.

The picture helps us to understand this: a blind old woman (Avijja is of feminine gender) with a stick picks her way through a petrified forest strewn with bones. It is said that the original picture here

should be an old blind she-camel led by a driver, the beast being one accustomed to long and weary journeys across inhospitable country, while its driver could be craving. Whichever simile is used, the beginninglessness and the

darkness of unknowing are well suggested. We are the blind ones who have staggered from the past into the present— to what sort of future?

Depending on the existence of unknowing in the heart there was volitional action, Kamma or abhisankhara, made in those past lives.

2nd Link: VOLITIONAL FORMATIONS (Sankhara)

Represented by a potter. Just as a potter forms clay into something new, an action begins a sequence that leads to

new consequences. Once put into motion, the potter's wheel continues to spin without much effort. Likewise, an action creates a predisposition in the mind.

Intentional actions have the latent Power within them to bear fruit in the future - either in a later part of the life in which they were performed, in the following life, or in some more distant life, but their

potency is not lost with even the passing of aeons; and whenever the necessary conditions obtain that past Kamma may bear fruit. Now, in past lives we have made Kamma, and due to our

ignorance of the Four Noble Truths we have been "world-upholders" and so making good and evil Kamma we have ensured the continued experience of this world.

Beings like this, obstructed by unknowing in their hearts have been compared to a potter making pots: he makes successful and beautiful pottery (skillful Kamma) and he is sometimes careless and his pots crack and break up

from various flaws (unskillful Kamma). And he gets his clay fairly well smeared over himself just as purity of heart is obscured by the mud of Kamma. The simile of the potter is particularly apt because the word

'Sankhara' means "forming," "shaping," and "compounding," and therefore it has often been rendered in English as "Formations."

Depending on the existence of these volitions produced in past lives, there arises the Consciousness called "relinking" which becomes the basis of this present life.

3rd Link: CONSCIOUSNESS (Vinnana)

The Rebirth consciousness or "consciousness that links on", is represented by a monkey going from window to window. This represents a single consciousness perceiving through the various sense organs. The

monkey represents the very primitive spark of sense-consciousness which is the first moment in the mental life of the new being.

This relinking consciousness may be of different qualities, according to the Kamma upon which it depends. In the case of all those who read this, the consciousness "leaping" into a new birth at the time of

conception, was a human relinking consciousness arising as a result of having practiced at least the Five Precepts, the basis of "humanness" in past lives. One should note that this relinking

consciousness is a resultant, not something which can be controlled by will. If one has not made Kamma suitable for becoming a human being, one cannot will, when the time of death comes round, "Now I shall become a man again!"

The time for intentional action was when one had the opportunity to practice Dhamma. Although our relinking-

consciousness in this birth is now behind us, it is now that we can practice Dhamma and make more sure of a favourable relinking consciousness in future—that is, if we wish to go on living in Samsara.

This relinking-consciousness is the third constituent necessary for conception, for even though it is the

mother’s period and sperm is deposited in the womb, if there is no "being" desiring to take Rebirth at that place and time there will be no fertilisation of the ovum.

Dependent upon relinking-consciousness there is the arising of Mind-body.

4th Link: MIND - BODY (nama-rupa)

Depicted by people sitting in a boat with one of them steering. The boat symbolises form, and its occupants, the mental aggregates.

This is not a very accurate translation but gives the general meaning. There is more included in rupa that is usually thought of as body, while mind is a compound of feeling, perception, volition and

consciousness. This mind and body is two interactive continuities in which there is nothing stable. Although in conventional speech we talk of "my mind" and "my body," implying

that there is some sort of owner lurking in the background, the wise understand that laws govern the workings of

both mental states and physical changes and mind cannot be ordered to be free of defilements, nor body told that it must not grow old, become sick and die.

But it is in the mind that a change can be wrought instead of drifting through life at the mercy of the inherent instability of mind and body. So in the illustration, mind is doing the work of punting the boat of

psycho-physical states on the river of cravings, while body is the passive passenger. The Tibetan

picture shows a coracle being rowed over swirling waters with three (? or four) other passengers, who doubtless represent the other groups or aggregates (khandha).

With the coming into existence of mind-body, there is the arising of the Six Sense-spheres.

5th Link: SIX SENSE - SPHERES (Salayatana)

Depicted by a house with six windows and a door. The senses are the 'portals' whereby we gain our impression of the world. Each of the senses is the manifestation of our desire to experience things in a particular way.

A house with six windows is the usual symbol for this link. These six senses are eye, ear, nose, tongue, touch and mind, and these are the bases for the reception of the

various sorts of information which each can gather in the presence of the correct conditions. This information falls under six headings corresponding to the six spheres: sights, sounds, smells,

tastes, tangibles and thoughts. Beyond these six spheres of sense and their corresponding six objective spheres, we know nothing. All our experience is limited by the senses and their objects

with the mind counted as the sixth. The five outer senses collect data only in the present but mind, the sixth, where this information is collected and processed, ranges through the three times adding

memories from the past and hopes and fears for the future, as well as thoughts of various kinds relating to the present. It may also add information about the spheres of

existence which are beyond the range of the five outer senses, such as the various heavens, the ghosts and

the hell-states. A mind developed through collectedness (Samadhi) is able to perceive these worlds and their inhabitants.

The six sense-spheres existing, there is Contact.

A couple embracing depicts the contact of the sense organs with there objects. With this link, the {{Wiki|psychophysical]] organism begins to interact with the world. The sensuous impression is symbolised by a

kiss. This indicates that there is a meeting with an object and a distinguishing of it prior to the production of feeling.

This means the contact between the six senses and the respective objects. For instance, when the necessary conditions are all fulfilled, there being an eye, a sight-object, light and the eye being functional

and the person awake and turned toward the object, there is likely to be eye-contact, the striking of the object

upon the sensitive eye-base. The same is true for each of the senses and their type of contact. The traditional symbol for this link shows a man and a woman embracing.

In dependence on sensuous impressions, arises Feeling.

7th Link: FEELING (Vedana)

Symbolised by an eye pierced by an arrow. The arrow represents sense data impinging on the sense organs, in this case the eye. In a very vivid way, the image suggests the strong feelings which sensory

experience evokes - although only painful feeling is here implied, both painful and pleasant are intended. Even a very small condition causes a great deal of feeling in the eye. Likewise, no

matter what kind of feeling we experience, painful or pleasurable, we are driven by it and conditioned by it.

When there have been various sorts of contact through the six senses, feelings arise which are the emotional response to those contacts. Feelings are of three sorts: pleasant, painful and neither pleasant nor

painful. The first are welcome and are the basis for happiness, the second are unwelcome and are the basis for Dukkha while the third are the neutral sort of feelings which we experience so often but hardly notice.

But all feelings are unstable and liable to change, for no mental state can continue in equilibrium. Even moments of the highest happiness whatever we consider this is, pass away and give place to different ones. So even

happiness which is impermanent based on pleasant feelings is really Dukkha, for how can the true

unchanging happiness be found in the unstable? Thus the picture shows a man with his eyes pierced by arrows, a strong enough illustration of this.

When feelings arise, Cravings are (usually) produced.

8th Link: CRAVING (Tanha)

Represented by a person drinking beer. Even though it harms you, no matter how much you drink, you just keep on drinking. Also known as attachment, it is a Mental factor that increases desire without any satisfaction.

Up to this point, the succession of events has been determined by past Kamma. Craving, however, leads to the making of new Kamma in the present and it is possible now, and only now, to practice Dhamma. What is

needed here is Mindfulness (sati), for without it no Dhamma at all can be practiced while one will be swept away by the force of past habits and let craving and unknowing increase themselves within one’s heart. When

one does have Mindfulness one may and can know "this is pleasant feeling," "this is unpleasant feeling," "this is neither pleasant nor unpleasant feeling"—and such contemplation of feelings leads one to understand and beware of greed, aversion and delusion, which are respectively associated with the three feelings. With

this knowledge one can break out of the Wheel of Birth and Death. But without this Dhamma-practice it is

certain that feelings will lead on to more cravings and whirl one around this wheel full of Dukkha. As Venerable Nagarjuna has said:

- "Desires have only surface sweetness,

- hardness within and bitterness deceptive as the kimpa-fruit.

- Thus says the King of Conquerors.

- Do likewise with desire.

- Which whirls the wheel of wandering-on

- and is the root of Suffering.

- No better thing to do!"

- L.K. 23, 104

In Sanskrit, the word trisna (Tanha) means thirst, and by extension implies "thirst for experience." For this reason, craving is shown as a toper guzzling intoxicants and in the picture has been

added more bottles representing craving for sensual sphere existence and the craving for the higher heavens of the Brahma-worlds which are either of subtle form, or formless.

Where the Kamma of further craving is produced there arises Grasping.

Represented by a monkey reaching for a fruit. Also known as clinging, it means mentally grabbing at an object one desires.

This is the mental state that clings to or grasps the object. Because of this clinging which is described as craving in a high degree, man becomes a slave to passion.

Upadana is fourfold:

1. Attachment to sensual pleasures; 2. Attachment to wrong and evil views; 3. Attachment to mere external observances, rites and rituals; and 4. Attachment to self, an erroneous lasting soul entity. Man entertains thoughts of craving, and in proportion as he fails to ignore them, they grow till they get intensified to the degree of tenacious clinging.

This is an intensification and diversification of craving which is directed to four ends: sensual pleasures, views which lead astray from Dhamma, external religious rites and vows, and

attachment to the view of soul or self as being permanent. When these become strong in people they cannot even become interested in Dhamma, for their efforts are directed away from Dhamma and towards

Dukkha. The common reaction is to redouble efforts to find peace and happiness among the objects which are grasped at. Hence both pictures show a man reaching up to pick more fruit although his basket is full already.

Where this grasping is found there Becoming is to be seen.

10th Link: BECOMING (Bhava)

Represented by a woman in late pregnancy. Just as she is about to bring forth a fully developed child, the Karma that will produce the next lifetime is fully potentialized though not yet manifest.

With hearts boiling with craving and grasping, people ensure for themselves more and more of various sorts of life, and pile up the fuel upon the fire of Dukkha. The ordinary person, not knowing about Dukkha,

wants to stoke up the blaze, but the Buddhist way of doing things is to let the fires go out for want of fuel by stopping the process of craving and grasping and thus cutting off Ignorance at its root. If we want to stay

in Samsara we must be diligent and see that our 'becoming', which is happening all the time shaped by our Kamma, is 'becoming' in the right direction. This means 'becoming' in the direction of purity and following the white

path of Dhamma-practice. This will contribute to whatever we become, or do not become, at the end of this life when the pathways to the various realms stand open and we 'become' according to our practice and to our death-consciousness.

In the presence of Becoming there is arising in a new birth.

This link is represented by the very explicit image of a woman giving birth to a child.

Birth means the appearance of the five aggregates (material form, feeling, perception, formation and consciousness)in the mother’s womb.

Birth, as one might expect, is shown as a mother in the process of childbirth, a painful business and a reminder of how Dukkha cannot be avoided in any life. Whatever the future life is to be, if we are not

able to bring the wheel to a stop in this life, certainly that future will arise conditioned by the Kamma made in this life. But it is no use thinking that since there are going to be future births,

one may as well put off Dhamma practice until then—for it is not sure what those future births will be like. And when they come around, they are just the present moment as well. So no use waiting!

Venerable Nagarjuna shows that it is better to extricate oneself:

- As well a mass of other ills.

- When birth’s no longer brought about.

- All the links are ever stopped."

- L.K. 111

Naturally where there is Birth, is also Old-age and Death.

12th Link: AGEING AND DEATH (jara-marana)

The final link is represented by a dying person. Ageing is both progressive, occurring every moment of our lifetime, and degenerative which leads to death.

In future one is assured, given enough of Unknowing and Craving, of lives without end but also of deaths with end. The one appeals to greed but the other arouses aversion. One without the other is impossible.

But this is the path of heedlessness. The Dhamma-path leads directly to Deathlessness, the going beyond birth and death, beyond all Dukkha.

We are well exhorted by the words of Acharya Nagarjuna:

"Do you therefore exert yourself:

- At all times try to penetrate Into the heart of these Four Truths;

- For even those who dwell at home,

- they will, by understanding them ford the river of (mental) floods."

- L.K. 115

This is a very brief outline of the workings of this wheel which we cling to for our own harm and the hurt of others. We are the makers of this wheel and the turners of this wheel, but if we wish it and work for it, we are the ones who can stop this wheel.

Conclusion

This Wheel of Life teaches us and reminds us of many important features of the Dhamma as it was intended to by the teachers of old. Contemplating all its features frequently helps to give us true insight into the

nature of Samsara. With its help and our own practice we come to see Dependent arising in ourselves. When

this has been done thoroughly all the riches of Dhamma will be available to us, not from books or discussions, nor from listening to others’ explanations...

The Exalted Buddha has said:

- "Whoever sees Dependent arising, he sees Dhamma;

- Whoever sees Dhamma, he sees Dependent arising."

- Conditions truly they are transient

- With the nature to arise and cease

- Having arisen, then they pass away

- Their calming, cessation is happiness.