BDud.rTsi – a Tibetan tale of soma

A Tibetan Buddhist text re-tells the Churning of the Ocean legend with several novel elements, some of which provide clues to the identity of amṛita. The text in question is the Immaculate Crystal Garland (Tib., Dri Med Zhal Phreng) a Tibetan work which, presumably, is itself a translation of a Sanskrit original. Despite the relative obscurity of this work, it was one of the first Tibetan texts ever translated into English. 1 Here is the tale it tells:

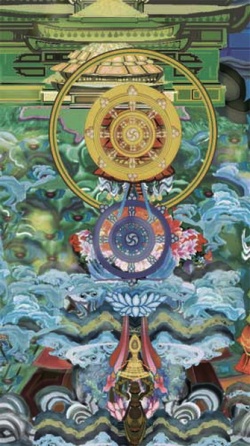

Once upon a time, evil demons, had unleashed the lethal hālāhala poison, with disastrous effect on all sentient beings, including mankind. Very concerned about this state of affairs, the Buddhas convened a true summit meeting – they met on top of the cosmic axis, Mount Meru. It was agreed by all the assembled Buddhas that the only solution was to provide the world with an antidote and the antidote par excellence was amṛita, elixir of immortality. Unfortunately, it lay concealed in the depths of the ocean. In order to procure the elixir they decided to churn the ocean, using Mount Meru as a churning stick, and so cause the water of life to rise to the surface of the waters. This they did, and gave the amṛita to the gentle bodhisattva Vajrapāṇi to keep it safe until the next Buddha-summit, when they would deliver it to all living beings.

However, the evil Rāhu, an asura,2 happened to hear of this precious discovery, and carefully watched Vajrapāṇi’s movements, waiting for a chance to snatch the elixir. An opportunity soon arose and as soon as Vajrapāṇi’s back was turned, Rāhu drank the entire world’s supply of the elixir of immortality. Then, as if the theft was not crime enough, to add insult to injury, he replaced the stolen amṛita with his own urine. Rāhu then hurried away as fast as possible, and had already traveled a considerable distance before Vajrapāṇi came home.

The only beings who witnessed the flight of Rāhu were the sun and moon but Rāhu threatened them with vengeance, if ever they should to betray him to Vajrapāṇi.

As soon as Vajrapāṇi discovered the theft, he set out in pursuit of the culprit but his searches proved fruitless. Eventually, he thought of asking the sun but the sun was evasive, saying that he had paid no particular attention as to who it was. The moon, on the other hand, replied honestly but begged Vajrapāṇi not to tell Rāhu. Armed with this this information, Vajrapāṇi rapidly found Rāhu and dealt him such a blow with his thunderbolt [i.e. vajra) that his upper body was lacerated all over and his lower half was completely obliterated. But despite his dreadful wounds, Rāhu could not die – the amṛita he had drunk protected him from death. This powerful elixir, however, dripped from his wounds and fell all over the world, causing numerous medicinal herbs to spring up wherever it touched the soil.

When the Buddhas re-convened their summit meeting, it was not to distribute the amṛita, as they had planned. Instead, they had to decide upon how to dispose of Rāhu’s urine. To pour it out would have been most dangerous to living beings, as it contained a large quantity of the hālāhala poison. So they decided that Vajrapāṇi should drink it, in just punishment for his carelessness in letting the amṛita be stolen.

As he drank Rāhu’s urine, Vajrapāṇi’s fair, golden complexion was transformed by the effects of the poison to dark blue, his jeweled ornaments – necklaces, bangles, ankle-bracelets and so on – all turned into snakes and he was surrounded in an aura of blazing fire. This transfiguration caused Vajrapāṇi to detest all evil demons, especially Rāhu.

Rāhu himself did not escape without punishment. The Buddhas re-assembled his shattered body but replaced his missing legs with the tail of a nāga,3 formed nine different heads from his broken one and placed a raven’s head on top. The large wound in his abdomen was made into an enormous mouth, and the lesser wounds into thousand of eyes.

After his transformation, Rāhu, who had always been wicked, became more evil than ever. His rage was directed especially towards the sun and the moon, who had betrayed him. He is constantly trying to devour them, particularly the moon, who displayed the most hostile disposition towards him. He overshadows them whilst trying to devour them, and thus causes eclipses; but owing to Vajrapāṇi’s unceasing vigilance, he never succeeds in destroying them.

Undoubtedly, the striking parallels between “The legend about Chakdor” and the Hindu legend of the origin of soma show that the Buddhist amṛita and the Hindu soma were at one time understood to be identical. Moreover, the principal property of amṛita is, to this day, perceived by Buddhists as being a species of inebriation, however symbolically this inebriation may be interpreted. Why else would barley beer (Tib., ch’ang) be used by yogins as a symbolic substitute for amṛita?4 Conversely, why else would Tibetans employ the term bDud.rTsi as a poetic synonym for beer?

This legend is noteworthy for several reasons. Firstly, Buddhist deities are mostly viewed as philosophical abstractions and, unlike the gods of Hinduism, do not normally appear as characters in cosmic dramas. This story of Vajrapāṇi and Rāhu is a rare example of a tale in which Buddhas and bodhisattvas behave as mythological entities. This is all the more reason to see this as a Buddhist redaction of a Hindu myth, specifically “the churning of the ocean.” The parallels to this myth are obvious, especially as some of the Hindu versions include an episode where Rāhu steals the soma, which then has to be rescued.

Vajrapāṇi (“thunderbolt in hand”) is, in part, a thinly disguised form of the Vedic god Indra, who was also known as “Vajrapāṇi”. Both gods use their thunderbolt to destroy a serpent-creature which, in Indra’s case, is the drought-demon Vṛitra. There are several accounts of the battle between Indra and Vṛitra but soma is involved with all of them. In one Indra quaffs copious draughts of soma before the battle. In another, Vṛitra has drunk all the soma, and in a third, Vṛitra is made of soma.

The disposal of Rāhu’s urine is clearly analogous to the passage in the Hindu myth in which Śiva drinks the hālāhala poison, resulting in his blue throat. In the Buddhist version, Rāhu’s urine is contaminated with hālāhala and drinking it turns Vajrapāṇi’s golden complexion dark blue. Curiously, it is Buddhism, the religion of forgiveness, mercy and self-sacrifice, in which Vajrapāṇi, forced to drink poisonous urine as punishment, develops a hatred of demons whereas in the Hindu version, Śiva selflessly drinks the hālāhala poison for the sake of all beings.

In addition to this unorthodox retelling of Hindu myths, the tale of Vajrapāṇi and Rāhu is partly an astrological allegory.5 According to folklore, Rāhu is the demon who causes eclipses and this story neatly rationalizes his motivation. It explains why Rāhu hates the sun and moon so much that he continually tries to swallow them and why he can never permanently contain them – they just escape through the huge mouth in his abdomen. In the same fairy-tale manner, the story explains how medicinal plants came about: they all sprang up together when the earth was showered with Rāhu’s blood. The amṛita contained in this blood gave these plants their healing properties but it was, after all, demon’s blood so beware, they may also be toxic.