The Shaman's Vision

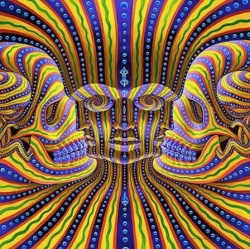

From the very beginning of human habitation in Tibet the principal religious preoccupation was with the harshness and hostility of the physical environment. Before Buddhism, with its emphasis on morality, awareness and liberation, can come into focus, it was and still is necessary to come to terms with the landscape and the elemental powers that inhabit it. Taming the landscape is the principal concern of the shaman and entering into his vision we enter the mythic realm of sacred Tibet.

The shaman's vision is a holistic vision where the distinction between the outer physical environment and the inner human being is blurred. In the shaman's mindscape there is no radical distinction between outer phenomena and inner noumena. Human consciousness encompasses the totality of possibility.

This is a pre-rational mindstate. The development of consciousness that occurred in the Western mind after the Renaissance and the scientific enlightenment with the growth of rational, logical, thought processes, undermined this holistic vision of reality.

As the conceptual capacity of the mind increased, so did our alienation from a sense of oneness with the environment. Outer phenomena became separate from us and became objects of alienated scientific observation.

An acute separation - a dualism - of self and other evolved. Rational consciousness, indeed, depends upon the suppression of the noumena of the holistic mind.

The alienated dualistic mindstate of Western man has grown like a cancer to the point where we can only gain access to vestiges of the holistic shamanistic vision by damaging the psyche and entering an atavistic stratum of consciousness that is conventionally labelled insane.

The argument between holistic shamanistic consciousness and rational dualistic mind is not relevant here. But it is necessary to accept the reality and validity of the holistic, mythic, vision of the shaman to understand the dimensions of his vision, his spiritualistic terminology and the methods he uses to transform the landscape and its spiritual phenomena, and to enter into sacred Tibet.

It may be useful to conceive of his vision as an internalisation of all apparently external phenomena through a process of 'seeing' that cuts through the duality of ordinary perception where self and other, physical and mental, inside and outside, are separate.

In the sphere of unitary perception all elements of every perceptual situation are interlinked: each sensory perception is a totality involving the entire cosmos, and thus it is called holistic - entire and complete.

The shaman is a magician able to manipulate, to pacify, to control or to subjugate the spiritualistic energies resident in the environment. These energies may be elemental, animal or vegetable, human or relating to the realms of gods, demons and spirits. Through his magic he can influence the elements responsible for rainfall, drought and flood, earthquake, avalanche and landslide, and thunder and lightening.

He can control the fertility of the soil assuring bounteous crops and averting famine. He can prevent diseases of men and cattle. He can protect the lives of men and women and the lives of their animals, the fertility of their crops, and their reproductive potency. He can foretell the future and influence family and political affairs.

The cosmology of the shaman's mythic realm is best described in the conventional shamanic terms of the three realms of existence. This is well known in Tibet, but also in its essence throughout South and South-East Asia.

The three realms of existence are the sky, the earth and the subterranean realm. These three spheres are inhabited and governed by three distinct categories of beings.

The gods live in the sky above, serpent spirits live in the earth below, and human beings live on the earth in between. In elemental terms, the sky above is the domain of space, air and fire, the subterranean realm is the sphere of earth and water, and all the elements are present in the middle realm, the domain of human beings.

By 'gods' is understood gods (lha), demons (dre) and the innumerable spirits of various kinds. Serpent spirits (lu, nagas) are demi-gods, and there are other various spirits that live in the netherworld. The human mind in the middle realm is the stage on which these gods, demons and spirits interact with human beings.

The sky-gods include the gods like Brahma of the Hindu pantheon and spirits like the Odour-eaters (driza), but the sky-gods who loom largest in the Tibetan mythic vision are those who live on the mountain peaks, the mountain gods (noijin and nyen).

These most powerful of the entities of the pantheon, male or female, seem actually to be confounded with the mountains themselves. They are warrior gods, quick to anger, jealous and violent, and their nature is power.

From the human point of view they are trouble-makers, tormentors, terrorists, devils, sitting on their mountain thrones raining down affliction, with little or no cause, upon their human quarry.

Their responses are like the reactions of irritable, violent, uptight drunks. Loitering on the passes, unless they are propitiated with offerings they are lethal to travellers - their breath is poisonous.

They shape-shift according to their mood and their need. The Indian yaksha Ravana, who abducted Rama's wife Sita to his Sri Lankan lair, was a mountain god, but he lacks the feral savagery of the Tibetan variety.

The mountain gods are territorial lords - the greater the mountain the greater their territory. Nyenchen Thanglha residing on the mountain of the same name in a range that dominates both the Northern Plains and Central Tibet is like the mountain god-king of the whole of Tibet.

The god of the mountain that physically dominates a valley probably rules that valley, as Yarlha Shampo, for example, rules the Yarlung Valley.

Every small valley has its own mountain residence of its mountain god. What ties the human inhabitants most securely to the mountain god and his whims and moods is their relationship of grandson to grandfather.

The mountain gods are the original ancestors of the tribes of Central Tibet and they have a certain responsibility to their offspring, although even careful ritual propitiation does not necessarily bring looked for protection from these irresponsible guardians.

They are as capricious as the weather, which is a principal method of cowing and tyrannising their progeny. Mountain gods are propitiated with complex ritual and offering.

The chief residents of the subterranean realm are the serpent spirits, demi-gods, male and female (lu and luma). They can be conceived animistically as the spirits of earth and water and everything that is contained within these elemental spheres. In a special way they are the guardians of ecological balance, a highly conservative force inhibiting human interference with the earth and what is in the earth.

They are the foot soldiers of a semi-divine natural authority that orders mankind's relationship with his terrestrial environment. While the mountain gods rule with a heavy-handed fickle patriarchal authority, the serpent spirits have allegiance to a thin-skinned, hypersensitive female nature, with a formidable armoury at their disposal.

The serpent spirits live in the earth, in the rock, and in the lakes and streams. Their usual form is snake-like. They are black, white or red. They can take human form or shape-shift according to requirement.

They guard the mineral wealth of the earth including rock and the soil itself. Precious stones belong to them and the magical power of a coral or turquoise stone is determined as auspicious or inauspicious according to its guardian serpent spirit's satisfaction regarding the manner in which it was mined and the care that has been taken of it.

To mine iron or gold is to offend the serpent spirits and is equivalent to stealing from them, unless a pact is agreed upon and propitiation made. The low status of iron-workers in traditional Tibet is due to their subordination to the serpent spirits.

Rock is also protected by them and they object to the movement of stones from one place to another, and, of course, the hewing of stone.

Propitiation of the serpent spirits precedes any building activity. Even to dig a hole in the ground is to risk offending them, and to plough the soil is to invade their domain and all agriculture is therefore dependant upon a working relationship with them. Trees and plants are also protected by the serpent spirits.

Although any of the gods, demons and spirits can afflict human beings with disease by creating an imbalance within the psycho-organism through the element with which they are identified, or acting on the level of human consciousness which gives them their existence, the serpent spirits are the chief arbiters of human health.

This power is derived chiefly from their affinity to water. As guardians of springs and water courses they protect the flow and the purity of water. In the cold Tibetan climate the danger from water-born intestinal disease is minimal compared to the peril on the Indian plains, but the pollution of water sources angers Tibetan serpent spirits no less than their Indian cousins.

Their ire afflicts those who fail in their hygiene. Serpent spirits also control the bag of leprosy and tuberculosis, and sores and itches are serpent-inflicted. Since the body is ninety-eight percent water, they have special admission to the psycho-organism and are the cause of diseases of bodily water imbalance such as abscesses, ulcers, and swelling of the limbs and dehydration.

Diseases related to excessive indulgence are also caused by the serpent spirits. The serpent spirits are propitiated with offering and herbal incense.

The female entity that can be conceived as the mistress of the legions of serpent spirits is the demoness (sinmo) who can be seen in the landscape. The demoness of Central Tibet, for example, lies supine across the central provinces, embodying all hostile elemental powers.

This demoness combines the chaotic, relentlessly destructive power of the external environment with the savage bestiality of the internally latent female archetype. Incarnate demonesses or rock-ogresses stalk the earth after human prey. They are the original inhabitants of Tibet in Buddhist mythology.

The specifically female sky-goddesses called sky dancers (khandromas, dakinis) share this elementally malign nature and, like the mother goddesses (mamo), may relate to men and eat his flesh and afflict him through sexual relationship.