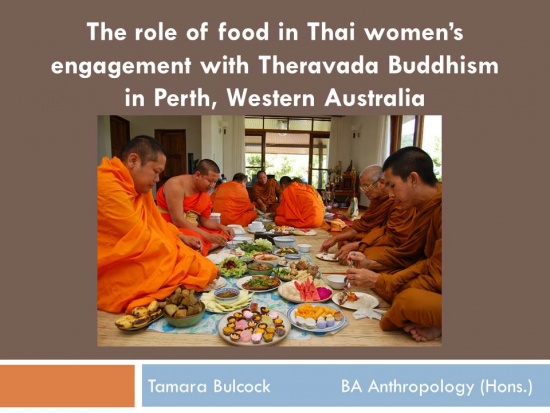

The role of food in Thai women's engagement with Theravada Buddhism in Western Australia by Tamara Bulcock

The role of food in Thai women's engagement with Theravada Buddhism in Western Australia

Ms. Tamara Bulcock, University of Western Australia

As an anthropology graduate from University of Western Australia, I intend to contribute to this year's conference by providing a paper which explores Buddhism in contemporary Australia form a social scientist's perspective. In addition to other perspectives at this conference which may explore philosophical or ascetic dimensions of Australian Buddhism, I hope to provide an insight into the social role of Theravada Buddhism in Western Australia by exploring some of my research examples specific to the Buddhist context in Perth and placing them into a broader understanding of social processes within Australian society.

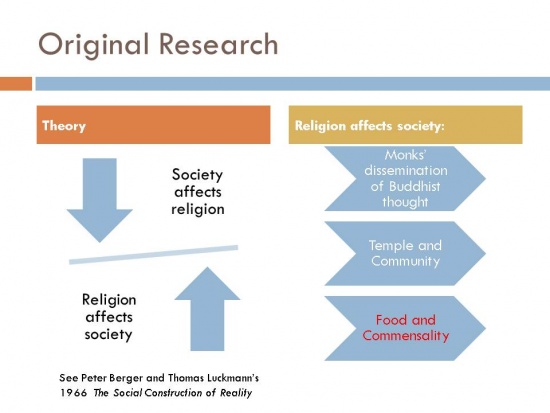

I submitted my Honours thesis in mid-2013. In a nutshell, my thesis argued that religion can shape migrant experiences of cultural adaptation and social integration. I demonstrated this by applying anthropological theories of religion and cultural adaptation to the experiences of Thai Buddhist women settling into Western Australian society. As an anthropological piece of research, my goal was to understand cultural differences, cross-cultural interaction and cultural integration from the perspective of those implicated in these process. To do this I employed ethnographic fieldwork techniques. This involved collecting qualitative data through immersion in the culture of interest, through in-depth interviews with key individuals and participant observation at Buddhist rituals and cultural events throughout the year.

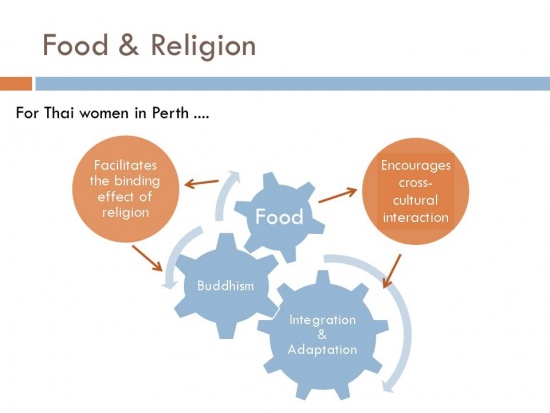

In this paper I will explore but one aspect of the ethnographic evidence I used to support my thesis argument. During my fieldwork it became abundantly clear to me how integral the role of food was, not only to the religious and social lives of the Thai Buddhist women I interviewed, but also to fundamental Buddhist rituals. This paper demonstrates how an anthropological understanding of the use of food in religious contexts can demonstrate one way in which the Western Australian Theravada Buddhist community can influence the cultural adaptation and social integration of Thai Buddhist women settling in Western Australia (WA).

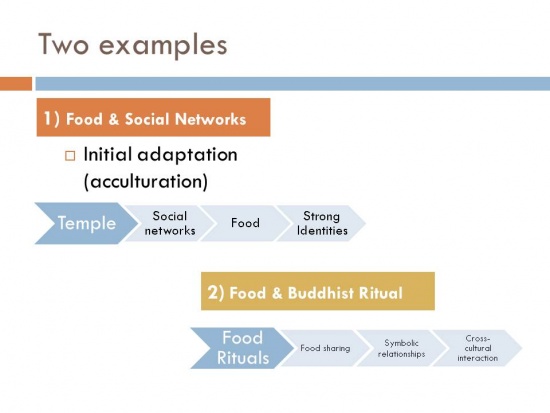

Broadly speaking, I observed at least two main ways in which Thai Buddhist women interact with food in religious contexts in WA. Analysing these cases from an anthropological perspective allows us to understand how food can be more than just a mundane necessity of everyday life; it can be laden with symbolic meaning and play a key role in the lives of Thai Buddhist women who are settling in WA and negotiating their cultural adaptation and social integration experiences. Firstly, I'd like to give an account of one of my interviewee's experiences, a woman named Kelly from Northeast Thailand who decided to migrate to Perth in 2000 after marrying her Australian husband. This was the first time Kelly had travelled outside of her home country. She described to me how she felt extremely lonely, scared and homesick during her first few months in Perth. She rarely left the house to meet other people and interacted only with her husband and his Australian friends. Struggling with limited English skills and feelings of isolation in a new and unfamiliar society, Kelly's husband located Dhammaloka temple in the telephone book for her.

Kelly described an immediate sense of relief and joy on first visiting the temple. Not only was she now in a familiar Buddhist context, she could talk in her mother tongue with other Thais. She could now engage with the Western monks who spoke Thai and offered both a culturally-familiar form of spiritual and psychological support, and practical advice and Buddhism-infused strategies for interacting with Australians and their social systems. Most importantly, access to the temple allowed Kelly to establish significant relationships with other Thai Buddhist women in Perth, linking her to an established social network. This network of mutual support provided Kelly with information about her new home that allowed her to begin interacting with and integrating into Western Australian society. Significantly, it opened the door for Kelly to find local Asian supermarkets and places to buy familiar foods from home, allowing her to cook those dishes she had been missing and ease her sense of isolation and homesickness.

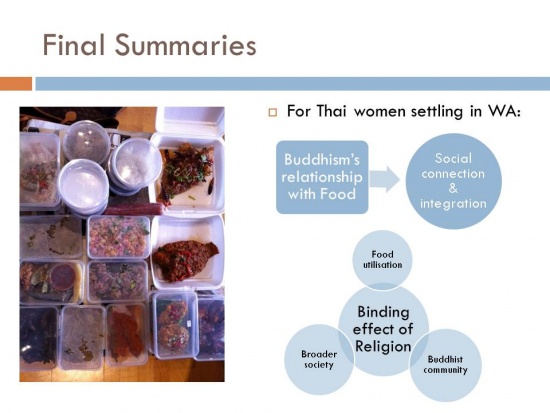

This was not just the case for Kelly, but also for the other two women I interviewed, and in turn others whom they described to me. Finally locating Asian food stores where they could buy special fruits and vegetables that could not be bought anywhere else meant that these Thai women could make the special dishes they were missing from home. Cooking a favourite or familiar dish re-established and reinforced their Thai cultural identity. This is an important part of successfully settling into culturally unfamiliar contexts for migrants (Berry 1992:72). Construction of a strong cultural identity can provide stability and reassurance for migrants through what can be tumultuous times during the acculturation process (Berry 1992:70). This process involves cultural changes (affecting the migrant's original values, attitudes and behaviours) which are negotiated in response to their continuous contact between two cultural groups, that of their society of origin and of the society of settlement (Berry 1992:69,70). For example, depending on the cultural changes that a migrant chooses, or if forced, to make during acculturation, this process may not necessarily lead to successful integration but could lead to assimilation, separation or marginalisation (Berry 1992:82). In adapting to Western Australian society change is unavoidable and loss of identity a distinct possibility. Thai Buddhist women can negotiate this change and continuity positively through recreating and consuming cultural cuisine which holds special significance for their cultural identity and collective memory (Janowski 2012:176).

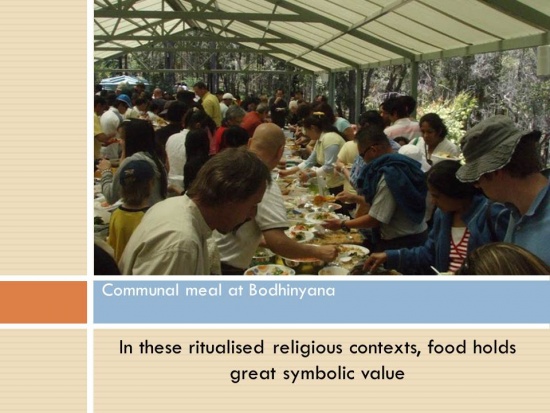

Food then offers them an avenue of self-determination during their experiences of cultural adaptation. Accessing, preparing and consuming distinctly national or ethnic foods is central to maintaining an identity which is both rooted in the original homeland and serves as a marker of that identity in the new homeland (Janowski 2012:178,179). Being a member of a religious community in Perth provides a sense of belonging and is a social platform from which migrants can make statements about their identity in their new home, helping them to adapt to their new society in WA. The Buddhist community of WA provides regular opportunities to participate in meaningful food rituals through dana ceremonies and to connect with social support systems of other Thai women who open the door to accessing Asian food stores. In this way Buddhism in WA provides a platform for Thai Buddhist women to reinforce their sense of belonging and distinct identity through food and commensality, and can play a positive role in their experiences of cultural adaptation. Food can not only be used to solidify cultural identity and membership in a minority community, but also in the creation and maintenance of significant social relationships (Mintz & Du Bois 2001:109). The second role that food plays for migrants which I wish to explore is epitomised in the many dana ceremonies I observed at both Dhammaloka and Bodhinyana as well as at the Kathina celebrations held at Jhana Grove. In this ritualised religious context food holds great symbolic value. As the monks are not permitted to handle money or prepare food, they are entirely dependent upon the Buddhist community to provide their daily meal, or dana. To begin with, lay people form a line along which the monks proceed with their alms bowls to receive the offering of rice. The rice is blessed by the lay person, and equal merit is gained by each layperson who gives to each monk, increasing their good kamma. It is considered taboo to taste any food intended for a monk before it has been offered as this taints the giver's good intentions to give freely and their ability to gain merit (Lindberg Falk 2007:140). Following this ritual, the monks partake in a meal consisting of the combined dishes provided by the lay congregation and prepared specifically for this purpose. Once the monks have taken their food, the entire lay congregation then share the combined dishes in a communal meal.

For Thai women who participate in this ritual, sharing the same food creates a link between them and other lay people and establishes that they are of the same community. Joint preparation of food to offer to the monks serves to identify the diverse laity as one community with a joint purpose - to support their Sangha. Because eating is almost always a group event, many migrants' primary relationships are forged through the sharing of food (Fox 2012:1). Food then becomes the focus of symbolic activity. It makes statements about the nature of our social connections and our place within society. Food becomes a symbol of who we are. Sharing religiously symbolic food, Thai women identify themselves with others by eating the same food in the same way (Fox 2012:2; Fischler 2011:533). This shared meal makes a statement: 'we are symbolically the same'. Over shared food Thai women connect with other Buddhists of different backgrounds and with their Australian families who attend these religious rituals. Membership in the Buddhist community then provides the basis for social connection between Thai Buddhist women and other Western Australians, and the sharing of food can be seen as a tangible sign of their interaction and integration with the broader Buddhist and mainstream society.

Eating in this ritual context transforms and reaffirms relationships not only with others who are visible, but also with the invisible. Symbolic food in religious contexts serves to connect the layperson with the sacred realm or cosmos, strengthening their belief and conviction in their religious system of meaning (Mintz & Du Bois 2002:107). Food itself can also be sacred through its association with transcendental processes, as is the case with the rice in this context. The symbolic value of the rice was demonstrated at the Kathina celebrations I attended, where the monks' alms bowls were continually filled, emptied and refilled by the lay congregation's offerings. This abundance of rice was then collected and later offered as part of the shared meal.

Participating in these food-related rituals can empower Thai Buddhist women socially. Women are often considered especially disempowered in migration contexts (Oyzurt 2009:6). As the traditional preparers and givers of food offerings to monks (both in Thai and Australian society) Thai women control the symbolic links between givers and receivers of food, and therefore play an integral role in defining religious relationships. Thai Buddhist women can control the symbolic underpinning of social interaction within the Buddhist community in Perth - food. They can then forge and maintain relationships within this sphere. These significant relationships can in themselves be emotional, financial and material resources to and are pivotal to migrants establishing themselves and defining their place within their new society. Buddhism can therefore be seen to instigate social connection and meaning making for Thai women settling in WA. The sourcing, preparing and sharing of food in Buddhist contexts is a central part of the acculturation processes of Thai women: not only does it redefine and re-establish cultural and religious identity, but also creates and maintains meaningful social relationships with those who are culturally similar (other Thai women) and instigates social connection and interaction with those who are culturally 'other' (non-Thai Buddhists and mainstream Australians).

The reason for this paper's focus on food in religious contexts, and the reason why I find it so fascinating, is because it is an example of but one way in which religion is a significant aspect of processes of social integration for migrants in Australian society. This religious aspect can easily be forgotten or ignored considering the tendency to emphasise ethnic pluralism when defining our as 'multicultural' and 'secular' Australian society. This analysis of food highlights the symbolic nature of religion - how it can be inadvertently imbued in the creation of something meaningful out of something mundane. This cuts right to the core of the definition of religion as a socially constructed source of meaning which people can use to inform their sense of self, their world around them and their place within that world[1]. Finally, I'd like to acknowledge that although food in Buddhist contexts plays a significant role in order to present a form of Buddhism that is not only relative to their ethnically-diverse laity but also to the social setting in which they live and interact with mainstream Australians (see Bulcock 2013). It is the monks as cultural negotiators who have actively forged a distinctly Western Australian Buddhism which migrants can use to inform their own negotiations in adapting and integrating into Western Australian society.

Footnotes

- ↑ My definition of religion employs a sociological consideration of religion as both an external phenomenon which can influence individuals' behaviour regardless of their subjective understandings, as well as a socially constructed source of meaning which individuals can use to form their self identity (Van Krieken et al 2010:350).

References

- Berry, John W 1992 ‘Acculturation and Adaptation in a New Society’, International Migration, v.30, no.1, pp.69-85.

- Bulcock, Tamara 2013 Exploring the dialectical relationship between religion and society through migrant experiences of cultural adaptation and social integration: The case of Thai women's engagement with Theravada Buddhism in Perth, Western Australia, Honours Thesis, The University of Western Australia.

- Fischler, Claude 2011 ‘Commensality, society and culture’, Social Science Information, v.50 n.3-4, pp.528-548.

- Fox, Robin 2012 Food and Eating: An Anthropological Perspective, Social Issues Research Centre, available from <http://www.sirc.org/publik/foxfood.pdf>

- Janowski, Monica 2012 ‘Introduction: Consuming Memories of Home in Constructing the Present and Imagining the Future’, Food and Foodways, v.20, pp.175-186.

- Lindberg Falk, Monica 2007 Making Fields of Merit: Buddhist Female Ascetics and Gendered Orders in Thailand, NIAS Press: Malaysia.

- Mintz, Sidney W. & Du Bois, Christine M. 2002, ‘The Anthropology of Food and Eating’, Annual Review of Anthropology, v.31, pp.99-119.

- Oyzurt, Saba Senses 2009 Integrating Muslim Immigrant Women in the United States and the Netherlands: Effects of Religiosity and Migrant Religious Institutions, PhD Thesis, University of California: Irvine.

Power Point Presentation

Source

By Ms. Tamara Bulcock, University of Western Australia

The third International Conference Buddhism & Australia 2014