Difference between revisions of "The Dharma Flower Sutra seen through the Oral Transmission of Nichiren Daishōnin: The Fourth Chapter on Faith Leading to Understanding"

(Created page with "{{DisplayImages|838|617|1340|924|630|877|726|1168|1439|71|639|915|82|1716|1220|685|1942|1339|396|256|272|1304|92|53|1811|1668|1682|139|2085|1677|190|358|433|1170|1480|805|988|...") |

m (Text replacement - "]]]" to "]])") |

||

| (7 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{DisplayImages|838|617|1340|924|630|877|726|1168|1439|71|639|915|82|1716|1220|685|1942|1339|396|256|272|1304|92|53|1811|1668|1682|139|2085|1677|190|358|433|1170|1480|805|988|177|635|1765|2086|350|1040|473|686|933|1699|582|628|1350|398|626|175|1395|383|687 | + | {{DisplayImages|838|617|1340|924|630|877|726|1168|1439|71|639|915|82|1716|1220|685|1942|1339|396|256|272|1304|92|53|1811|1668|1682|139|2085|1677|190|358|433|1170|1480|805|988|177|635|1765|2086|350|1040|473|686|933|1699|582|628|1350|398|626|175|1395|383|687}} |

{{Centre|<big><big>The Dharma Flower Sutra<br/> seen through the Oral Transmission of<br/> [[Nichiren Daishōnin]]</big></big>}} | {{Centre|<big><big>The Dharma Flower Sutra<br/> seen through the Oral Transmission of<br/> [[Nichiren Daishōnin]]</big></big>}} | ||

| − | The first important point, concerning Faith Leading to Understanding. | + | The first important point, concerning [[Faith]] Leading to [[Understanding]]. |

| − | In the sixth volume of the Notes on the Textual Explanation of the Dharma Flower Sutra, it says that in the earliest translation of this sutra by Dharmaraksha, entitled the Sutra on the Lotus Blossom of the Correct Dharma (Shōhokkekyō), the title of this chapter is called the | + | In the sixth volume of the Notes on the Textual Explanation of the [[Dharma]] [[Flower Sutra]], it says that in the earliest translation of this [[sutra]] by [[Dharmaraksha]], entitled the [[Sutra]] on the [[Lotus]] Blossom of the Correct [[Dharma]] ([[Shōhokkekyō]]), the title of this [[chapter]] is called the “[[Chapter]] on the [[Delight]] in [[Faith]] (Shingyō hon)”. Although this rendering communicates something of the meaning given by [[Kumārajīva]] ([[Kumarajū]]), the [[word]] “[[delight]]” does not really express the [[idea]] of [[understanding]], or taking in, the contents of the [[teaching]]. |

| − | This chapter shows how four of Shākyamuni’s disciples – Shubodai (Subhuti), Kassenen (Katyāyama), Kashō (Mahākashyapa), and Mokuren (Maudgalyāna), who were people who exerted themselves to attain the highest stage of the teachings of the individual vehicle (shōjō, hīnayāna) through listening to the Buddha (shōmon, shrāvaka) – became awakened to the concept of the one vehicle of the Buddha that leads to enlightenment. Should we use the word | + | This [[chapter]] shows how four of [[Shākyamuni’s]] [[disciples]] – [[Shubodai]] ([[Subhuti]]), Kassenen (Katyāyama), [[Kashō]] (Mahākashyapa), and [[Mokuren]] ([[Maudgalyāna]]), who were [[people]] who exerted themselves to attain the [[highest]] stage of the teachings of the [[individual vehicle]] (shōjō, [[hīnayāna]]) through listening to the [[Buddha]] ([[shōmon]], [[shrāvaka]]) – became [[awakened]] to the {{Wiki|concept}} of the one [[vehicle]] of the [[Buddha]] that leads to [[enlightenment]]. Should we use the [[word]] “[[delight]]”? |

| − | The Oral Transmission on the Meaning of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Ongi Kuden) says, “Out of the twenty-eight chapters that comprise the Sutra on the White Lotus Flower-like Mechanism of the Utterness of the Dharma (Myōhō Renge Kyō), in which each chapter has its own title, Faith Leading to Understanding has to be the title of this particular chapter.” | + | The [[Oral Transmission]] on the Meaning of the [[Dharma Flower Sutra]] ([[Ongi Kuden]]) says, “Out of the twenty-eight chapters that comprise the [[Sutra on the White Lotus Flower]]-like {{Wiki|Mechanism}} of the Utterness of the [[Dharma]] ([[Myōhō Renge Kyō]]), in which each [[chapter]] has its [[own]] title, [[Faith]] Leading to [[Understanding]] has to be the title of this particular [[chapter]].” |

| − | The validity of the concept of the one instant of thought containing three thousand existential spaces is brought about through faith. Also all the Buddhas of the past, present, and future attained the path of enlightenment through this single ingredient of faith. This idea of faith is the sharp sword that cuts away the inherent ignorance and unknowing that impedes and distracts us from the possibilities of enlightenment. | + | The validity of the {{Wiki|concept}} of the [[one instant of thought]] containing three thousand [[existential]] spaces is brought about through [[faith]]. Also all the [[Buddhas]] of the {{Wiki|past}}, {{Wiki|present}}, and {{Wiki|future}} [[attained]] the [[path]] of [[enlightenment]] through this single ingredient of [[faith]]. This [[idea]] of [[faith]] is the sharp sword that cuts away the [[inherent]] [[ignorance]] and unknowing that impedes and distracts us from the possibilities of [[enlightenment]]. |

| − | Tendai (T’ien T’ai) once stated that | + | [[Tendai]] ([[T’ien T’ai]]) once stated that “[[Faith]] means to have no [[doubts]].” Hence, [[faith]] is the keen blade that cuts away [[doubt]] and {{Wiki|bewilderment}}. [[Faith]] is comparable to the value we attach to a [[gem]], whereas [[understanding]] is like the [[gem]] itself. The [[wisdom]] and [[discernment]] of all the [[Buddhas]] of the {{Wiki|past}}, {{Wiki|present}}, and {{Wiki|future}} is acquired through the one [[word]] of [[faith]]. |

| − | [That wisdom is Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō, which means to devote our lives to and found them on (Nam[u]) the Utterness of the Dharma (Myōhō, Saddharma) permeated by the underlying white lotus flower-like mechanism of the interdependence of cause, concomitancy and effect (Renge) in its whereabouts of the ten realms of dharmas (Kyō).] | + | [That [[wisdom]] is [[Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō]], which means to devote our [[lives]] to and found them on (Nam[u]) the Utterness of the [[Dharma]] ([[Myōhō]], [[Saddharma]]) permeated by the underlying [[white lotus]] flower-like {{Wiki|mechanism}} of the [[interdependence]] of [[cause]], concomitancy and effect ([[Renge]]) in its whereabouts of the [[ten realms]] of [[dharmas]] ([[Kyō]]).] |

| − | Faith is what brings into reality the wisdom and discernment of the Buddha teaching. This entails giving a name to and imbibing into our consciousness that all sentient beings are endowed with the nature of the Buddha. Outside of faith or being absolutely convinced of the Dharma of enlightenment, there can be no real understanding of what the Buddha teaching is about. Also, without an understanding of what the Buddha teaching involves, there can be no real faith in it. It is through the single word of | + | [[Faith]] is what brings into [[reality]] the [[wisdom]] and [[discernment]] of the [[Buddha]] [[teaching]]. This entails giving a [[name]] to and imbibing into our [[consciousness]] that all [[sentient beings]] are endowed with the [[nature]] of the [[Buddha]]. Outside of [[faith]] or being absolutely convinced of the [[Dharma]] of [[enlightenment]], there can be no real [[understanding]] of what the [[Buddha]] [[teaching]] is about. Also, without an [[understanding]] of what the [[Buddha]] [[teaching]] involves, there can be no real [[faith]] in it. It is through the single [[word]] of “[[faith]]” that the [[seeds]] of [[enlightenment]] are sown. |

| − | Now, because Nichiren and those that follow him accept with faith and dedicate themselves to the title Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō – which means to devote our lives to and found them on (Nam[u]) the Utterness of the Dharma (Myōhō) [entirety of existence] permeated by the underlying white lotus flower-like mechanism of the interdependence of cause, concomitancy and effect (Renge) in its whereabouts of the ten [psychological] realms of dharmas (Kyō) – they come into possession of the all-embracing gem that is “the unsought and spontaneously obtained cluster of | + | Now, because [[Nichiren]] and those that follow him accept with [[faith]] and dedicate themselves to the title [[Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō]] – which means to devote our [[lives]] to and found them on (Nam[u]) the Utterness of the [[Dharma]] ([[Myōhō]]) [entirety of [[existence]]) permeated by the underlying [[white lotus]] flower-like {{Wiki|mechanism}} of the [[interdependence]] of [[cause]], concomitancy and effect ([[Renge]]) in its whereabouts of the ten ([[psychological]]) [[realms]] of [[dharmas]] ([[Kyō]]) – they come into possession of the all-embracing [[gem]] that is “the unsought and spontaneously obtained cluster of [[jewels]]”. [[Faith]] is what brings about [[wisdom]] and [[discernment]]. But a lack of [[faith]] will lead [[people]] back into [[realms]] of [[suffering]] ([[jigoku]], [[hell]]). |

| − | Also, The Oral Transmission on the Meaning of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Ongi Kuden) affirms that faith is synonymous with the principle of the eternal, unchanging, and real essentials of existence. This would correspond to Tendai’s (T’ien T’ai) statement, | + | Also, The [[Oral Transmission]] on the Meaning of the [[Dharma Flower Sutra]] ([[Ongi Kuden]]) affirms that [[faith]] is {{Wiki|synonymous}} with the [[principle]] of the [[eternal]], [[unchanging]], and real [[essentials]] of [[existence]]. This would correspond to Tendai’s ([[T’ien T’ai]]) statement, “[[Faith]] is the single, all-pervasive [[principle]] of the real aspect of all [[dharmas]]. This means that every single [[dharma]] is endowed with the [[nature]] of the [[Buddha]] (issaihō kaize buppō).” [[Understanding]] is the [[wisdom]] that is always in accordance with the sequence of [[karmic]] circumstances and the [[self]] received [[wisdom]] of [[Buddhahood]] that is used by those who are [[enlightened]] ([[jijuyūchi]]). |

| − | In the ninth volume of the Textual Explanation of the Meaning of the Dharma Flower Sutra, it says that to have faith [in the Buddha teaching] means to have no doubts about it. In the sixth volume of the Textual Explanation of the Meaning of the Dharma Flower Sutra, it says that, when those disciples of the Buddha who had average propensities, such as Shubodai (Subhuti), Kasennen (Kātyāyana), Kashō, and Mokuren (Maudgalyāna), had listened to Shākyamuni’s discourse on using similes and parables as an expedient means for communicating the ultimate truth, they were able to throw away their doubts and bewilderment and arrived at understanding all the implications of the path of the universal vehicle (daijō, mahāyāna). Therefore, this has to be referred to as faith. Their progress into | + | In the ninth volume of the Textual Explanation of the Meaning of the [[Dharma]] [[Flower Sutra]], it says that to have [[faith]] [in the [[Buddha]] [[teaching]]) means to have no [[doubts]] about it. In the sixth volume of the Textual Explanation of the Meaning of the [[Dharma]] [[Flower Sutra]], it says that, when those [[disciples]] of the [[Buddha]] who had average propensities, such as [[Shubodai]] ([[Subhuti]]), [[Kasennen]] ([[Kātyāyana]]), [[Kashō]], and [[Mokuren]] ([[Maudgalyāna]]), had listened to [[Shākyamuni’s]] {{Wiki|discourse}} on using similes and [[parables]] as an [[expedient means]] for communicating the [[ultimate truth]], they were able to throw away their [[doubts]] and {{Wiki|bewilderment}} and arrived at [[understanding]] all the implications of the [[path]] of the [[universal vehicle]] ([[daijō]], [[mahāyāna]]). Therefore, this has to be referred to as [[faith]]. Their progress into practicing the [[path]] of the [[universal vehicle]] ([[daijō]], [[mahāyāna]]) is termed as “[[understanding]]”. |

| − | It says, in the Notes of the Textual Explanation of the Dharma Flower Sutra that, for those who aspire to the universal vehicle (daijō, mahāyāna), the two words | + | It says, in the Notes of the Textual Explanation of the [[Dharma Flower Sutra]] that, for those who aspire to the [[universal vehicle]] ([[daijō]], [[mahāyāna]]), the two words “[[faith]]” and “[[understanding]]” refer to the [[two paths]] of 1) desistance from troublesome worries ([[bonnō]], [[klesha]]) by {{Wiki|concentrating}} on the [[principle]] of the [[eternal]], [[unchanging]], and real [[essential]] of [[existence]]. [For those who [[practice]] the [[Kōmon]] teachings of the [[Nichiren]] Schools, this means the Fundamental [[Object]] of Veneration ([[gohonzon]]).] This [[practice]] frees us from [[doubt]] and therefore can be [[thought]] of as [[faith]] which leads into 2) being able to see clearly, which is [[understanding]]. The [[word]] “[[faith]]” has the implication of these [[two paths]], but the [[word]] “[[understanding]]” is only applicable as to how much [[practice]] we do. The [[path]] of practise is referred to as [[understanding]]. |

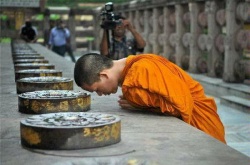

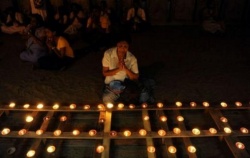

| − | At that time, Shudodai, Kasennen (Kātyāyana), Kashō, and Mokuren (Maudgalyāna), whose personalities and lives were based on wisdom, heard the Dharma which was pronounced by the Buddha that was without any precedent. When the World Honoured One made the declaration that Sharihotsu would attain the unexcelled and all-embracing enlightenment of Buddhahood (anokutara sanmyaku sanbodai, anuttara-samyak-sambodhi), they were seized up in an extraordinary state of mind that filled them with an overwhelming sense of joy. They stood up from their seats, adjusted their robes, bared their right shoulders, knelt with their right knee on the ground, and, with a singleness of mind, they put the palms of their hands together and bowed in reverence, lifting their eyes in deference towards the Tathāgata. | + | At that [[time]], Shudodai, [[Kasennen]] ([[Kātyāyana]]), [[Kashō]], and [[Mokuren]] ([[Maudgalyāna]]), whose personalities and [[lives]] were based on [[wisdom]], heard the [[Dharma]] which was pronounced by the [[Buddha]] that was without any precedent. When the [[World]] Honoured One made the declaration that [[Sharihotsu]] would attain the unexcelled and all-embracing [[enlightenment]] of [[Buddhahood]] ([[anokutara sanmyaku sanbodai]], [[anuttara-samyak-sambodhi]]), they were seized up in an [[extraordinary]] [[state of mind]] that filled them with an overwhelming [[sense]] of [[joy]]. They stood up from their seats, adjusted their [[robes]], bared their right shoulders, knelt with their right knee on the ground, and, with a [[singleness]] of [[mind]], they put the palms of their hands together and [[bowed]] in reverence, lifting their [[eyes]] in deference towards the [[Tathāgata]]. |

| − | Then they addressed him in these terms: We who have been placed at the head of the community of monks and nuns (sō, sangha) are now, with the passing of the years, stricken with old age. We assume that we have already reached nirvana and are unable to take on further responsibilities. We no longer think of progressing towards the attainment of the unexcelled and correct, all-embracing enlightenment of Buddhahood (anokutara sanmyaku sanbodai, anuttara-samyak-sambodhi). | + | Then they addressed him in these terms: We who have been placed at the head of the [[community of monks]] and [[nuns]] (sō, [[sangha]]) are now, with the passing of the years, stricken with [[old age]]. We assume that we have already reached [[nirvana]] and are unable to take on further responsibilities. We no longer think of progressing towards the [[attainment]] of the unexcelled and correct, all-embracing [[enlightenment]] of [[Buddhahood]] ([[anokutara sanmyaku sanbodai]], [[anuttara-samyak-sambodhi]]). |

| − | World Honoured One, for a long time now you have been expounding what the Dharma is. All this time, we have been seated in our places, with our worn-out bodies, only thinking of the relativity in the non-substantiality of our mental perceptions (kū, shūnyatā), which, in themselves, have a non-characteristic essence (musō), and the non-substantiality of the essence of existence that is not produced by causation and is incapable of coming into existence or ceasing to exist (musa). As for the enjoyment of the reaches of the minds of bodhisattvas, or the clearing of the space in our minds where Buddhahood will come into being, or even bringing ordinary people to such a | + | [[World]] Honoured One, for a long [[time]] now you have been expounding what the [[Dharma]] is. All this [[time]], we have been seated in our places, with our worn-out [[bodies]], only [[thinking]] of the [[relativity]] in the [[non-substantiality]] of our [[mental]] [[perceptions]] ([[kū]], shūnyatā), which, in themselves, have a non-characteristic [[essence]] (musō), and the [[non-substantiality]] of the [[essence]] of [[existence]] that is not produced by [[causation]] and is incapable of coming into [[existence]] or ceasing to [[exist]] (musa). As for the [[enjoyment]] of the reaches of the [[minds]] of [[bodhisattvas]], or the clearing of the [[space]] in our [[minds]] where [[Buddhahood]] will come into being, or even bringing [[ordinary people]] to such a [[realization]], then our [[minds]] are unable to be intrigued with such things. |

| − | What is the reason for this? It is because the World Honoured One has brought about our departure from the threefold realm of existence [1) where sentient beings have appetites and desires, 2) which are incarnated in a subjective materiality with physical surroundings, 3) who, at the same time, are endowed with the immateriality of the realms of fantasies, dreams, thoughts and ideas (sangai, triloka)] and allowed us to substantiate the total extinction of nirvana. Furthermore, now we are all infirm and have grown old, whereas the Buddha is teaching and bringing bodhisattvas to the realisation of the unexcelled, and correct all-embracing enlightenment of Buddhahood, (anokutara sanmyaku sanbodai, anuttara-samyak-sambodhi), which does not give us the least bit of joy. | + | What is the [[reason]] for this? It is because the [[World]] Honoured One has brought about our departure from the [[threefold realm]] of [[existence]] [1) where [[sentient beings]] have appetites and [[desires]], 2) which are [[incarnated]] in a [[subjective]] [[materiality]] with [[physical]] surroundings, 3) who, at the same [[time]], are endowed with the immateriality of the [[realms]] of fantasies, [[dreams]], [[thoughts]] and [[ideas]] ([[sangai]], [[triloka]])] and allowed us to substantiate the total [[extinction]] of [[nirvana]]. Furthermore, now we are all infirm and have grown old, whereas the [[Buddha]] is [[teaching]] and bringing [[bodhisattvas]] to the realisation of the unexcelled, and correct all-embracing [[enlightenment]] of [[Buddhahood]], ([[anokutara sanmyaku sanbodai]], [[anuttara-samyak-sambodhi]]), which does not give us the least bit of [[joy]]. |

| − | Now, in the presence of the Tathāgata, we hear him confer onto people who have exerted themselves to attain the highest stage of the individual vehicle (shōjō, hīnayāna) through listening to the Buddha, as well as intellectual seekers (shōmon, shrāvaka), the prediction of their future attainment of the unexcelled and correct, all-embracing enlightenment of Buddhahood. At this, we are overcome with a joyous state of mind that we have never experienced before. We did not think that now and so suddenly we would get to hear such a rare Dharma and are benefitted and full of joy to obtain such an all-embracing (dai) goodness. We have got hold of a treasure of incalculable worth, without having to search for it. | + | Now, in the presence of the [[Tathāgata]], we hear him confer onto [[people]] who have exerted themselves to attain the [[highest]] stage of the [[individual vehicle]] (shōjō, [[hīnayāna]]) through listening to the [[Buddha]], as well as [[intellectual]] seekers ([[shōmon]], [[shrāvaka]]), the {{Wiki|prediction}} of their {{Wiki|future}} [[attainment]] of the unexcelled and correct, all-embracing [[enlightenment]] of [[Buddhahood]]. At this, we are overcome with a [[joyous]] [[state of mind]] that we have never [[experienced]] before. We did not think that now and so suddenly we would get to hear such a rare [[Dharma]] and are benefitted and full of [[joy]] to obtain such an all-embracing (dai) [[goodness]]. We have got hold of a [[treasure]] of [[incalculable]] worth, without having to search for it. |

| − | World Honoured One, what we would like to do now is to recount a parable and simile, which will make the meaning of all of this clear. | + | [[World]] Honoured One, what we would like to do now is to recount a [[parable]] and simile, which will make the meaning of all of this clear. |

| − | Let us imagine that there was a man who, since his boyhood, had abandoned his father, by running away from home, and who had lived, for a long time, in another country . . . | + | Let us [[imagine]] that there was a man who, since his boyhood, had abandoned his father, by running away from home, and who had lived, for a long [[time]], in another country . . . |

| − | The second important point, concerning the sentence, “Let us imagine there was a man who, since his boyhood, had abandoned his father, by running away from home, and who had lived, for a long time, in another country.” | + | The second important point, concerning the sentence, “Let us [[imagine]] there was a man who, since his boyhood, had abandoned his father, by running away from home, and who had lived, for a long [[time]], in another country.” |

| − | In the Textual Explanation of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke Mongu), it says, “by abandoning his father and running away”. Here, ‘to abandon’ implies the repudiation of the universal vehicle (daijō, mahāyāna). ‘To run’ means to envelop oneself in the obscurity and unclearness of unenlightenment. ‘Away’ takes on the meaning of turning back towards the karmic directions of living and dying. | + | In the Textual Explanation of the [[Dharma Flower Sutra]] (Hokke Mongu), it says, “by [[abandoning]] his father and running away”. Here, ‘to abandon’ implies the repudiation of the [[universal]] [[vehicle]] ([[daijō]], [[mahāyāna]]). ‘To run’ means to envelop oneself in the {{Wiki|obscurity}} and unclearness of [[unenlightenment]]. ‘Away’ takes on the meaning of turning back towards the [[karmic]] [[directions]] of living and dying. |

| − | In The Oral Transmission on the Meaning of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Ongi Kuden), it says that the concept of fatherhood can be understood in three ways. The first is the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō) in the sense of Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō as the underlying essence of all existence. The second is the Shākyamuni of the Sixteenth Chapter on the Lifespan of the Tathāgata and the third concept is Nichiren, who is the Lord, Teacher, and Father as well as the personification of the first two concepts. | + | In The [[Oral Transmission]] on the Meaning of the [[Dharma]] [[Flower Sutra]] ([[Ongi Kuden]]), it says that the {{Wiki|concept}} of fatherhood can be understood in [[three ways]]. The first is the [[Dharma]] [[Flower Sutra]] ([[Hokke-kyō]]) in the [[sense]] of [[Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō]] as the underlying [[essence]] of all [[existence]]. The second is the [[Shākyamuni]] of the Sixteenth [[Chapter]] on the [[Lifespan]] of the [[Tathāgata]] and the third {{Wiki|concept}} is [[Nichiren]], who is the [[Lord]], [[Teacher]], and Father as well as the {{Wiki|personification}} of the first two [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]]. |

| − | The Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō), which is the essential teaching according to the enlightenment of the Buddha as well as all the implications of Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō, is the father of all sentient beings. If we turn our backs on this sutra, it would mean that we continually live and die in the three realms of existence, as sufferers in the hells, as hungry ghosts, or as animals, or as the bombastic and aggressive shura (ashura), humankind, or as one of the deva (ten). | + | The [[Dharma]] [[Flower Sutra]] ([[Hokke-kyō]]), which is the [[essential]] [[teaching]] according to the [[enlightenment]] of the [[Buddha]] as well as all the implications of [[Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō]], is the father of all [[sentient beings]]. If we turn our backs on this [[sutra]], it would mean that we continually live and [[die]] in the [[three realms of existence]], as sufferers in the [[hells]], as [[hungry ghosts]], or as [[animals]], or as the bombastic and aggressive [[shura]] ([[ashura]]), humankind, or as one of the [[deva]] (ten). |

| − | Again, the Shākyamuni of the Sixteenth Chapter on the Lifespan of the Tathāgata, by being the realm of Buddhahood and the personification of the very life of all sentient beings is their father. Turning our backs on this Buddha means revolving uninterruptedly through all the paths of existence. | + | Again, the [[Shākyamuni]] of the Sixteenth [[Chapter]] on the [[Lifespan]] of the [[Tathāgata]], by being the [[realm]] of [[Buddhahood]] and the {{Wiki|personification}} of the very [[life]] of all [[sentient beings]] is their father. Turning our backs on this [[Buddha]] means revolving uninterruptedly through all the [[paths]] of [[existence]]. |

| − | Now, Nichiren is the father of all the sentient beings of the world of humankind (Nihon Koku). | + | Now, [[Nichiren]] is the father of all the [[sentient beings]] of the [[world]] of humankind (Nihon [[Koku]]). |

| − | The Universal Teacher Shōan, in his explanations of the meaning of the Sutra on the Buddha’s passing over to Nirvana, says, “A person who rids others of their slander and repudiation of the Dharma, as well as of their wrongdoings, is behaving as a parent.” | + | The [[Universal]] [[Teacher]] Shōan, in his explanations of the meaning of the [[Sutra]] on the [[Buddha’s]] [[passing over]] to [[Nirvana]], says, “A [[person]] who rids others of their [[slander]] and repudiation of the [[Dharma]], as well as of their wrongdoings, is behaving as a parent.” |

| − | To repudiate the universal vehicle (daijō, mahāyāna), in the sense of the phrase a few paragraphs above, means to repudiate Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō, which means to turn one’s life to and found it on (Nam) the Utterness of the Dharma (Myōhō) [entirety of existence] permeated by the underlying white lotus flower-like mechanism of the interdependence of cause, concomitancy and effect (Renge) in its whereabouts of the ten [psychological] realms of dharmas (Kyō). | + | To repudiate the [[universal]] [[vehicle]] ([[daijō]], [[mahāyāna]]), in the [[sense]] of the [[phrase]] a few paragraphs above, means to repudiate [[Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō]], which means to turn one’s [[life]] to and found it on (Nam) the Utterness of the [[Dharma]] ([[Myōhō]]) [entirety of [[existence]]) permeated by the underlying [[white lotus]] flower-like {{Wiki|mechanism}} of the [[interdependence]] of [[cause]], concomitancy and effect ([[Renge]]) in its whereabouts of the ten ([[psychological]]) [[realms]] of [[dharmas]] ([[Kyō]]). |

| − | The obscurity and unclearness of unenlightenment means the doubts, bewilderment as to the meaning of life, along with the rejection and vilification of the truth of the Dharma of the enlightened. To envelop oneself in the obscurity and unclearness of not wanting to understand the truth of the Dharma is to be like the perverse monks, such as Hōnen, Kōbō, Jikaku, Chishō, Dōryū, and Ryōkan, who, by choice, waywardly cover up the fact that they misrepresent and twist the profound meaning of the Buddha teaching. | + | The {{Wiki|obscurity}} and unclearness of [[unenlightenment]] means the [[doubts]], {{Wiki|bewilderment}} as to the meaning of [[life]], along with the rejection and vilification of the [[truth]] of the [[Dharma]] of the [[enlightened]]. To envelop oneself in the {{Wiki|obscurity}} and unclearness of not wanting to understand the [[truth]] of the [[Dharma]] is to be like the perverse [[monks]], such as [[Hōnen]], [[Kōbō]], [[Jikaku]], [[Chishō]], Dōryū, and [[Ryōkan]], who, by choice, waywardly cover up the fact that they misrepresent and twist the [[profound meaning]] of the [[Buddha]] [[teaching]]. |

| − | ( . . . and who had, for a long time, lived in another country) for perhaps ten years, twenty years, or even fifty years. The years had gone by, and he had already become a mature adult, but his poverty and difficulties had only increased. | + | ( . . . and who had, for a long [[time]], lived in another country) for perhaps ten years, twenty years, or even fifty years. The years had gone by, and he had already become a mature adult, but his {{Wiki|poverty}} and difficulties had only increased. |

| − | The third important point, concerning the phrase, “. . . but his poverty and difficulties had only increased.” | + | The third important point, concerning the [[phrase]], “. . . but his {{Wiki|poverty}} and difficulties had only increased.” |

| − | In the sixth volume of the Textual Explanation of the Meaning of the Dharma Flower Sutra, it says, “When one cannot find the necessary means to separate ourselves and get deliverance from the cycles of living and dying, then it is also a way of being in need.” | + | In the sixth volume of the Textual Explanation of the Meaning of the [[Dharma Flower Sutra]], it says, “When one cannot find the necessary means to separate ourselves and get [[deliverance]] from the cycles of living and dying, then it is also a way of being in need.” |

| − | The Oral Transmission on the Meaning of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Ongi Kuden)states that the necessary means to separate ourselves and get deliverance from the cycles of living and dying is through the resources of having a mind of faith in reciting Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō. This means to return our lives to and base them on (Nam[u]) the Utterness of the Dharma (Myōhō) [entirety of existence] permeated by the underlying white lotus flower-like mechanism of the interdependence of cause, concomitancy and effect (Renge) in its whereabouts of the ten [psychological] realms of dharmas (Kyō). | + | The [[Oral Transmission]] on the Meaning of the [[Dharma Flower Sutra]] ([[Ongi Kuden]])states that the necessary means to separate ourselves and get [[deliverance]] from the cycles of living and dying is through the resources of having a [[mind]] of [[faith]] in reciting [[Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō]]. This means to return our [[lives]] to and base them on (Nam[u]) the Utterness of the [[Dharma]] ([[Myōhō]]) [entirety of [[existence]]) permeated by the underlying [[white lotus]] flower-like {{Wiki|mechanism}} of the [[interdependence]] of [[cause]], concomitancy and effect ([[Renge]]) in its whereabouts of the ten ([[psychological]]) [[realms]] of [[dharmas]] ([[Kyō]]). |

| − | Now Nichiren and those who follow him are free from this kind of poverty and need, because they have accepted and hold to the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō) as Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō. | + | Now [[Nichiren]] and those who follow him are free from this kind of {{Wiki|poverty}} and need, because they have accepted and hold to the [[Dharma]] [[Flower Sutra]] ([[Hokke-kyō]]) as [[Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō]]. |

| − | Again, when we comply with reverence to the Utterness of the Dharma (Myōhō, Saddharma), the fires of the eight kinds of troublesome worries (bonnō, klesha) – which are 1) being born or coming into the world, 2) growing up towards old age, 3) ailments and sickness, 4) the uncertainties about death, 5) the suffering that comes about when we are separated from those whom we love, 6) the painfulness that we feel when we meet those whom we dislike and resent, 7) the disappointment of not finding something we seek, 8) and when the five aggregates that darken the awareness of the original enlightenment [which are i. having a bodily form which is ii. able to sense and feel through our eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, and the functioning of the mind or senses in connection with affairs and things, iii. conception or discerning the function of the mind that distinguishes, iv. the function of the mind in likes, dislikes, good, or evil, etc., v. the mental faculty that makes us think we are who we are on account of what we know] – all these devouring elements become the opening up of our awareness of the fire of the sagacity of the self received entity of wisdom, which is used by the Tathāgata and is the enlightenment of the original Buddha. | + | Again, when we comply with reverence to the Utterness of the [[Dharma]] ([[Myōhō]], [[Saddharma]]), the fires of the eight kinds of troublesome worries ([[bonnō]], [[klesha]]) – which are 1) being born or coming into the [[world]], 2) growing up towards [[old age]], 3) {{Wiki|ailments}} and [[sickness]], 4) the uncertainties about [[death]], 5) the [[suffering]] that comes about when we are separated from those whom we [[love]], 6) the painfulness that we [[feel]] when we meet those whom we dislike and resent, 7) the disappointment of not finding something we seek, 8) and when the [[five aggregates]] that darken the [[awareness]] of the original [[enlightenment]] [which are i. having a [[bodily]] [[form]] which is ii. able to [[sense]] and [[feel]] through our [[eyes]], {{Wiki|ears}}, {{Wiki|nose}}, {{Wiki|tongue}}, [[body]], and the functioning of the [[mind]] or [[senses]] in connection with affairs and things, iii. {{Wiki|conception}} or discerning the [[function of the mind]] that distinguishes, iv. the [[function of the mind]] in likes, dislikes, good, or [[evil]], etc., v. the [[mental]] {{Wiki|faculty}} that makes us think we are who we are on account of what we know] – all these devouring [[elements]] become the opening up of our [[awareness]] of the [[fire]] of the sagacity of the [[self]] received [[entity]] of [[wisdom]], which is used by the [[Tathāgata]] and is the [[enlightenment]] of the original [[Buddha]]. |

| − | As a vagrant he strayed in all directions, in search of food and any kind of clothing. Gradually, his wanderings led him into the direction of his father’s palace. His father had been searching for him since he ran away, but he had never found him. | + | As a vagrant he strayed in all [[directions]], in search of [[food]] and any kind of clothing. Gradually, his wanderings led him into the [[direction]] of his father’s palace. His father had been searching for him since he ran away, but he had never found him. |

| − | At that time, the father was staying in a city where his household was endowed with an enormous wealth of gold, silver, lapis lazuli, coral, amber, crystal, and pearls, and other such materials. All his warehouses were crammed to overflowing. He had many servants, custodians and their assistants, along with workers and other hired labourers. He also had elephants, horses, coaches and other vehicles as well as cattle and sheep without number. His profits came from financial transactions, which were spread out to far and distant countries. His merchants, dealers, and other traders were also extremely numerous. | + | At that [[time]], the father was staying in a city where his household was endowed with an enormous [[wealth]] of {{Wiki|gold}}, {{Wiki|silver}}, [[lapis lazuli]], [[coral]], {{Wiki|amber}}, {{Wiki|crystal}}, and {{Wiki|pearls}}, and other such materials. All his warehouses were crammed to overflowing. He had many servants, custodians and their assistants, along with workers and other hired {{Wiki|labourers}}. He also had [[elephants]], [[horses]], coaches and other vehicles as well as cattle and {{Wiki|sheep}} without number. His profits came from financial transactions, which were spread out to far and distant countries. His {{Wiki|merchants}}, dealers, and other traders were also extremely numerous. |

| − | One day, this destitute son, who had wandered from village to village, roaming through one country to the next, eventually arrived in the city where his father was living. The father continually had thoughts about his son, even though they had been separated for fifty years or more. Also, he never spoke about this state of affairs to anybody. He only fostered this situation in his mind, keeping his regrets and pining to himself. | + | One day, this destitute son, who had wandered from village to village, roaming through one country to the next, eventually arrived in the city where his father was living. The father continually had [[thoughts]] about his son, even though they had been separated for fifty years or more. Also, he never spoke about this [[state]] of affairs to anybody. He only fostered this situation in his [[mind]], keeping his regrets and pining to himself. |

| − | The fourth important point, concerning the sentence, “He only fostered this situation in his mind, keeping his regrets and pining to himself.” | + | The fourth important point, concerning the sentence, “He only fostered this situation in his [[mind]], keeping his regrets and pining to himself.” |

| − | In the sixth volume of the Textual Explanation of the Meaning of the Dharma Flower Sutra, it says that the word “regrets” summarises the mental state of the father, and to ‘pine’ summarises that of the son. | + | In the sixth volume of the Textual Explanation of the Meaning of the [[Dharma]] [[Flower Sutra]], it says that the [[word]] “regrets” summarises the [[mental state]] of the father, and to ‘pine’ summarises that of the son. |

| − | The Oral Transmission on the Meaning of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Ongi Kuden) says that all the sentient beings in the realms of humankind (Nippon no kuni) are comparable to the son, whereas Nichiren is like the father. All these sentient beings, through having lost faith in the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō) and having fallen into the hells of incessant suffering, feel vindictive about their situation and hate Nichiren for it. | + | The [[Oral Transmission]] on the Meaning of the [[Dharma]] [[Flower Sutra]] ([[Ongi Kuden]]) says that all the [[sentient beings]] in the [[realms]] of humankind (Nippon no kuni) are comparable to the son, whereas [[Nichiren]] is like the father. All these [[sentient beings]], through having lost [[faith]] in the [[Dharma]] [[Flower Sutra]] ([[Hokke-kyō]]) and having fallen into the [[hells]] of {{Wiki|incessant}} [[suffering]], [[feel]] vindictive about their situation and [[hate]] [[Nichiren]] for it. |

| − | Nichiren never spared his own voice in telling people not to abandon the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō), which implies establishing our lives on life itself; otherwise, they might regret not reaching Spirit Vulture Peak (Ryōjusen, Gridhrakūta). [Spirit Vulture Peak (Ryōju-sen, Gridhrakuta) is a mountain in northern India, where the Buddha Shākyamuni expounded the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō), as well as other teachings. Here, this term is used to symbolise the karmic destiny, the environment, and the terrain of enlightenment.] | + | [[Nichiren]] never spared his [[own]] {{Wiki|voice}} in telling [[people]] not to abandon the [[Dharma]] [[Flower Sutra]] ([[Hokke-kyō]]), which implies establishing our [[lives]] on [[life]] itself; otherwise, they might [[regret]] not reaching [[Spirit]] [[Vulture Peak]] ([[Ryōjusen]], [[Gridhrakūta]]). ([[Spirit]) [[Vulture Peak]] (Ryōju-sen, [[Gridhrakuta]]) is a mountain in {{Wiki|northern India}}, where the [[Buddha]] [[Shākyamuni]] expounded the [[Dharma]] [[Flower Sutra]] ([[Hokke-kyō]]), as well as other teachings. Here, this term is used to symbolise the [[karmic]] [[destiny]], the {{Wiki|environment}}, and the terrain of [[enlightenment]].] |

| − | Again in the sixth volume of the Textual Explanation of the Meaning of the Dharma Flower Sutra, it says, “The phrase ‘keeping his regrets and pining to himself’ means that the father pined and regretted that, in the past, he was not diligent enough in the education of his son in teaching and motivating him. As a result, the son ran away from home, ignoring his filial obligations, by rejecting and snubbing his parents and becoming friendly with bad influences.” | + | Again in the sixth volume of the Textual Explanation of the Meaning of the [[Dharma]] [[Flower Sutra]], it says, “The [[phrase]] ‘keeping his regrets and pining to himself’ means that the father pined and regretted that, in the {{Wiki|past}}, he was not diligent enough in the [[education]] of his son in [[teaching]] and motivating him. As a result, the son ran away from home, ignoring his filial obligations, by rejecting and snubbing his [[parents]] and becoming friendly with bad [[influences]].” |

| − | Nevertheless, the father thought to himself that he had now grown old and feeble. Also, at the same time, his warehouses were lavishly full, and yet his son had not returned. One day he would die, all his riches would be scattered, and there was no one to succeed him. He had always remembered his son with affection. Again he contemplated that, if he could find his son to whom he could bequeath his wealth, he would then become serene and happy, without any anxieties or worries. | + | Nevertheless, the father [[thought]] to himself that he had now grown old and feeble. Also, at the same [[time]], his warehouses were lavishly full, and yet his son had not returned. One day he would [[die]], all his riches would be scattered, and there was no one to succeed him. He had always remembered his son with {{Wiki|affection}}. Again he contemplated that, if he could find his son to whom he could bequeath his [[wealth]], he would then become [[serene]] and [[happy]], without any anxieties or worries. |

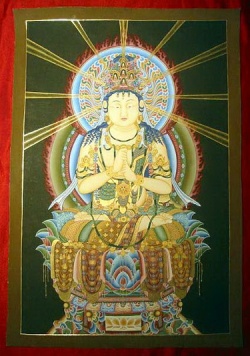

| − | World Honoured One, at that time, the impoverished son, who had drifted from one temporary employer to the next, wandered to the palace where his father was living. He stopped by the side of the gateway, where he saw his father further back in the courtyard, seated upon a lion throne with his feet upon a stool made of precious materials, whilst Brahmins, members of the warrior caste, as well as clerks, were all milling around him respectfully. His person was adorned with pearl collar bands and bracelets, which would be valued at thousands of myriads. Custodians and servants were standing in attendance to the left and the right of him, with bleached cotton cloth in their hands. | + | [[World]] Honoured One, at that [[time]], the impoverished son, who had drifted from one temporary employer to the next, wandered to the palace where his father was living. He stopped by the side of the gateway, where he saw his father further back in the courtyard, seated upon a [[lion throne]] with his feet upon a stool made of [[precious]] materials, whilst [[Brahmins]], members of the [[warrior]] [[caste]], as well as clerks, were all milling around him respectfully. His [[person]] was adorned with {{Wiki|pearl}} collar bands and bracelets, which would be valued at thousands of myriads. Custodians and servants were [[standing]] in attendance to the left and the right of him, with bleached cotton cloth in their hands. |

| − | Above his head, there was an awning of fine fabric, from which there were suspended various banners of superb quality. The ground was drenched in scented water and strewn with exquisite flowers. There were all sorts of valuable articles spread about him, which had either been taken out of storage or were to be put back in the warehouses. Either they had just arrived or else they were being given out. With such an array of adornment and finery, the father made an impression of particular magnificence. | + | Above his head, there was an awning of fine fabric, from which there were suspended various banners of superb quality. The ground was drenched in scented [[water]] and strewn with exquisite [[flowers]]. There were all sorts of valuable articles spread about him, which had either been taken out of storage or were to be put back in the warehouses. Either they had just arrived or else they were being given out. With such an array of adornment and finery, the father made an [[impression]] of particular [[magnificence]]. |

| − | The indigent son, on seeing the authority swayed by his father, was overtaken with fear and anxiety and regretted that he had even come to such a place. Surreptitiously, the thought came into the impoverished son’s mind: Either this person is a king or even equal to a sovereign. This is not a place where I should try to find some kind of work in order to help me get by. It would be better to go to some wretched village, where there is land upon which I can put forth my energy, and where it will be easier to earn my keep for food and clothing. If I stay here any longer, I will be arrested and forced to do very hard labour. After thinking things over in this manner, he quickly left and ran away. | + | The indigent son, on [[seeing]] the authority swayed by his father, was overtaken with {{Wiki|fear}} and [[anxiety]] and regretted that he had even come to such a place. Surreptitiously, the [[thought]] came into the impoverished son’s [[mind]]: Either this [[person]] is a [[king]] or even {{Wiki|equal}} to a sovereign. This is not a place where I should try to find some kind of work in order to help me get by. It would be better to go to some wretched village, where there is land upon which I can put forth my [[energy]], and where it will be easier to earn my keep for [[food]] and clothing. If I stay here any longer, I will be arrested and forced to do very hard labour. After [[thinking]] things over in this [[manner]], he quickly left and ran away. |

| − | At that moment, his father, who was this wealthy elder, immediately recognised his son from where he was sitting on the lion throne. His heart was filled with great joy, and he had the following thoughts: Now there is someone to whom I can bequeath all my wealth and all that there is in my warehouses. I have always thought about and borne in mind this son of mine. Nevertheless, he suddenly turned up all on his own. My wishes have been fulfilled more than I dared expect. I have now become aged and infirm, and yet I have been prey to my wishes and regrets. | + | At that [[moment]], his father, who was this wealthy elder, immediately recognised his son from where he was sitting on the [[lion throne]]. His [[heart]] was filled with great [[joy]], and he had the following [[thoughts]]: Now there is someone to whom I can bequeath all my [[wealth]] and all that there is in my warehouses. I have always [[thought]] about and borne in [[mind]] this son of mine. Nevertheless, he suddenly turned up all on his [[own]]. My wishes have been fulfilled more than I dared expect. I have now become aged and infirm, and yet I have been prey to my wishes and regrets. |

Thereupon he sent attendants to chase after him. Soon these servants had caught up and snatched at him, in order to bring him back to the elder. | Thereupon he sent attendants to chase after him. Soon these servants had caught up and snatched at him, in order to bring him back to the elder. | ||

| − | The impoverished son was seized with fright, thinking it was something to do with people who disliked him, and called out loudly, “I haven’t committed a criminal offence. Why are you trying to arrest me?” | + | The impoverished son was seized with fright, [[thinking]] it was something to do with [[people]] who disliked him, and called out loudly, “I haven’t committed a criminal offence. Why are you trying to arrest me?” |

| − | The attendants only held on to the impoverished son even harder, so as to forcibly take him back to the elder. The son then thought to himself: Without having committed a crime, I am now under arrest. Without a doubt, I will be put to death. His terror increased so much that he fainted and fell unconscious to the ground. | + | The attendants only held on to the impoverished son even harder, so as to forcibly take him back to the elder. The son then [[thought]] to himself: Without having committed a [[crime]], I am now under arrest. Without a [[doubt]], I will be put to [[death]]. His {{Wiki|terror}} increased so much that he fainted and fell [[unconscious]] to the ground. |

| − | The father, seeing all this from a distance, called to the attendants, “I have no need for this man, and there is no need to bring him here by force. Throw some water on his face, so that he regains consciousness. But do not say anything to him.” | + | The father, [[seeing]] all this from a distance, called to the attendants, “I have no need for this man, and there is no need to bring him here by force. Throw some [[water]] on his face, so that he regains [[consciousness]]. But do not say anything to him.” |

| − | What was the reason for this? The father understood that his son was motivated by unsavory and paltry inclinations and that his own wealth and dignity would be an obstacle to any further relationship. Even though the elder was certain about this person being his son, as an expediency he decided not to openly say that this pauper was his own offspring. | + | What was the [[reason]] for this? The father understood that his son was motivated by unsavory and paltry inclinations and that his [[own]] [[wealth]] and [[dignity]] would be an [[obstacle]] to any further relationship. Even though the elder was certain about this [[person]] being his son, as an expediency he decided not to openly say that this pauper was his [[own]] offspring. |

The attendants said to the impoverished son, “Now we will let you go free. You can go wherever you wish.” | The attendants said to the impoverished son, “Now we will let you go free. You can go wherever you wish.” | ||

| − | The indigent son felt as though he had never been happier in his life. He got up from the ground and made his way to some miserable village, in order to earn his food and clothing. Then the elder, wishing to entice his son, set up a ruse in order to lure him back. The elder secretly sent out two thin and emaciated servants without any apparent dignity or influence, to follow the impoverished son saying, “You must go to him and gently and skilfully suggest that there is employment here and he will earn twice the amount he is earning now. If this vagrant agrees, then you must bring him back here and make him work. If he asks what sort of work he is expected to do, you must tell him it is to sweep and clear away excrements and that you two will be working beside him.” | + | The indigent son felt as though he had never been [[happier]] in his [[life]]. He got up from the ground and made his way to some [[miserable]] village, in order to earn his [[food]] and clothing. Then the elder, wishing to entice his son, set up a ruse in order to lure him back. The elder secretly sent out two thin and emaciated servants without any apparent [[dignity]] or influence, to follow the impoverished son saying, “You must go to him and gently and skilfully suggest that there is employment here and he will earn twice the amount he is earning now. If this vagrant agrees, then you must bring him back here and make him work. If he asks what sort of work he is expected to do, you must tell him it is to sweep and clear away {{Wiki|excrements}} and that you two will be working beside him.” |

| − | Thereupon the two servants as envoys set about looking for the indigent son. When they had found him, they told him in detail everything that the father had said, and he accepted the offer. However, first the indigent son received his wages, and then he swept and cleared away excrements with the other two servants. | + | Thereupon the two servants as envoys set about looking for the indigent son. When they had found him, they told him in detail everything that the father had said, and he accepted the offer. However, first the indigent son received his wages, and then he swept and cleared away {{Wiki|excrements}} with the other two servants. |

| − | The father looked upon his son in doubt and ambiguity. Another day, over the sill of one of the windows, he saw his son tattered, thin, and emaciated, covered in excrement, dust, sweat, and dirt. The elder took off his more dignified upper garment, along with the necklace he was wearing, and put on working clothes that were smothered in different sorts of filth and grease. Dressed in this way, he said to the people who were working, “You must both work hard; I don’t want to see any shirking or loitering.” | + | The father looked upon his son in [[doubt]] and {{Wiki|ambiguity}}. Another day, over the sill of one of the windows, he saw his son tattered, thin, and emaciated, covered in excrement, dust, {{Wiki|sweat}}, and dirt. The elder took off his more dignified upper garment, along with the necklace he was wearing, and put on working [[clothes]] that were smothered in different sorts of filth and grease. Dressed in this way, he said to the [[people]] who were working, “You must both work hard; I don’t want to see any shirking or loitering.” |

| − | Taking advantage of this situation the elder now had an opportunity to approach his son. Later, he said to him, “Well now, my man, continue working here, and don’t go anywhere else. I’ll increase your wages, and all your needs such as crockery, rice, salt and spices will be looked after. You must not worry about your needs. There is even an elderly servant that can be given to you, if you have any need of one. I assure you he is very good. I, myself, will be like a father to you, and you have nothing to worry about. If you want to know why, then it is because I have become an old man, and you are still in your prime. Whenever I see you at work, I do not see in you the pettiness and faults of the others, such as their laziness and dodging work, as well as their anger and resentful tongues. From now on, you will be like my son, as the one I should have fathered.” | + | Taking advantage of this situation the elder now had an opportunity to approach his son. Later, he said to him, “Well now, my man, continue working here, and don’t go anywhere else. I’ll increase your wages, and all your needs such as crockery, {{Wiki|rice}}, [[salt]] and spices will be looked after. You must not {{Wiki|worry}} about your needs. There is even an elderly servant that can be given to you, if you have any need of one. I assure you he is very good. I, myself, will be like a father to you, and you have nothing to {{Wiki|worry}} about. If you want to know why, then it is because I have become an old man, and you are still in your prime. Whenever I see you at work, I do not see in you the pettiness and faults of the others, such as their [[laziness]] and dodging work, as well as their [[anger]] and resentful tongues. From now on, you will be like my son, as the one I should have fathered.” |

| − | From then on, the elder gave him a name and called him his son, whereupon the indigent son was overjoyed at this good fortune and at least no longer thought of himself as a casual labourer who was one of the outcasts of society. | + | From then on, the elder gave him a [[name]] and called him his son, whereupon the indigent son was overjoyed at this good [[fortune]] and at least no longer [[thought]] of himself as a [[casual]] labourer who was one of the outcasts of {{Wiki|society}}. |

| − | It was on account of all this that he was constantly made to clear away excrements, for over a period of twenty years. At the end of this period, both father and son understood each other. The son could come and go as he wished, even though he preferred to stay in his own lodgings. | + | It was on account of all this that he was constantly made to clear away {{Wiki|excrements}}, for over a period of twenty years. At the end of this period, both father and son understood each other. The son could come and go as he wished, even though he preferred to stay in his [[own]] lodgings. |

| − | World Honoured One, at about that time, the elder became ill, and he realised that his own death was near at hand. So he said to his son who had been a pauper, “At this time my warehouses are crammed to the full, with gold, silver, and other precious materials. You must get to know in detail how much is in each of the warehouses, what is to go out, and what is expected to come in. Such is my intention, and you must be aware of my state of mind. Why should it be so? There is no difference between you and me. Now, you must be even more prudent, so there will be no losses.” | + | [[World]] Honoured One, at about that [[time]], the elder became ill, and he realised that his [[own]] [[death]] was near at hand. So he said to his son who had been a pauper, “At this [[time]] my warehouses are crammed to the full, with {{Wiki|gold}}, {{Wiki|silver}}, and other [[precious]] materials. You must get to know in detail how much is in each of the warehouses, what is to go out, and what is expected to come in. Such is my [[intention]], and you must be {{Wiki|aware}} of my [[state of mind]]. Why should it be so? There is no difference between you and me. Now, you must be even more prudent, so there will be no losses.” |

| − | From the moment the once indigent son had received his instructions, he got to know backwards and forwards all the numerous possessions of the elder – his gold, silver, and other precious materials, as well as all that was in his warehouses. Nevertheless, he had not the slightest wish to be the owner of any of this wealth, not even what would amount to the equivalent of a meal. On the contrary, he still continued to live in his original lodging and was yet apparently unable to give up his own gross and base-minded way of thinking. | + | From the [[moment]] the once indigent son had received his instructions, he got to know backwards and forwards all the numerous possessions of the elder – his {{Wiki|gold}}, {{Wiki|silver}}, and other [[precious]] materials, as well as all that was in his warehouses. Nevertheless, he had not the slightest wish to be the [[owner]] of any of this [[wealth]], not even what would amount to the {{Wiki|equivalent}} of a meal. On the contrary, he still continued to live in his original lodging and was yet apparently unable to give up his [[own]] gross and base-minded way of [[thinking]]. |

| − | After a certain period, the father realised that his son’s way of thinking had gradually matured and he had finally realised a more universal way of thinking and thus rejected his former state of mind. The elder, on his deathbed, assembled all his relatives, the sovereign of the land, his ministers, members of the warrior caste, and the Brahmin scribes. | + | After a certain period, the father realised that his son’s way of [[thinking]] had gradually matured and he had finally realised a more [[universal]] way of [[thinking]] and thus rejected his former [[state of mind]]. The elder, on his deathbed, assembled all his relatives, the sovereign of the land, his ministers, members of the [[warrior]] [[caste]], and the [[Brahmin]] scribes. |

| − | Then he made the following proclamation: “Gentlemen, I would like to let you know that this person is my son whom I myself have fathered, who, in such-and-such a city, abandoned me, by running away from home. As a result, he was on his own and suffered bitterly for fifty or more years. His original family name is ‘what’s-his-name’, and my name is ‘what’s-his-name’ also. A long time ago, in the city of my birth, he ran away from home, and, at that time, I was eaten up with anguish. I searched for him over the years. Then, all of a sudden, he turned up here quite by chance. This person is indeed my son, and I am really his father. All the wealth that I now possess will become the property of my son. Also, he is fully aware of all the previous expenses and revenues in the accounts.” | + | Then he made the following proclamation: “Gentlemen, I would like to let you know that this [[person]] is my son whom I myself have fathered, who, in such-and-such a city, abandoned me, by running away from home. As a result, he was on his [[own]] and [[suffered]] [[bitterly]] for fifty or more years. His original family [[name]] is ‘what’s-his-name’, and my [[name]] is ‘what’s-his-name’ also. A long [[time]] ago, in the city of my [[birth]], he ran away from home, and, at that [[time]], I was eaten up with anguish. I searched for him over the years. Then, all of a sudden, he turned up here quite by chance. This [[person]] is indeed my son, and I am really his father. All the [[wealth]] that I now possess will become the property of my son. Also, he is fully {{Wiki|aware}} of all the previous expenses and revenues in the accounts.” |

| − | World Honoured One, when the formerly indigent son heard his father’s announcement, he was overjoyed. It was all beyond his expectations. Then the thought came to him: In the beginning, I never had the mind to seek anything whatsoever, and now all these stores of riches have come to me, all on their own. | + | [[World]] Honoured One, when the formerly indigent son heard his father’s announcement, he was overjoyed. It was all beyond his expectations. Then the [[thought]] came to him: In the beginning, I never had the [[mind]] to seek anything whatsoever, and now all these stores of riches have come to me, all on their [[own]]. |

| − | World Honoured One, this extremely wealthy elder symbolises the Tathāgata. We ourselves are all like the children of the Buddha, who has so often referred to those who hold faith in his teachings as his children. | + | [[World]] Honoured One, this extremely wealthy elder symbolises the [[Tathāgata]]. We ourselves are all like the children of the [[Buddha]], who has so often referred to those who hold [[faith]] in his teachings as his children. |

| − | World Honoured One, it is because of the three kinds of pain (sanku), which are either from direct causes, or due to some kind of loss or deprivation, or on account of the passing or impermanency of all dharmas, that we go through the cycles of living and dying, where we undergo the troublesome worries (bonnō, klesha) and passionate emotions that bring about suffering (netsunō). Even though we may be aware of these kinds of shortcomings, we cannot act on anyone’s advice, because we are attached to those passions. Therefore, through our bewilderment and confusion, we unintentionally and instinctively get enjoyment from our attachment to petty vices. | + | [[World]] Honoured One, it is because of the three kinds of [[pain]] (sanku), which are either from direct [[causes]], or due to some kind of loss or deprivation, or on account of the passing or [[impermanency]] of all [[dharmas]], that we go through the cycles of living and dying, where we undergo the troublesome worries ([[bonnō]], [[klesha]]) and [[passionate]] [[emotions]] that bring about [[suffering]] (netsunō). Even though we may be {{Wiki|aware}} of these kinds of shortcomings, we cannot act on anyone’s advice, because we are [[attached]] to those [[passions]]. Therefore, through our {{Wiki|bewilderment}} and {{Wiki|confusion}}, we unintentionally and instinctively get [[enjoyment]] from our [[attachment]] to petty [[vices]]. |

| − | Now on this day, World Honoured One, we have been pondering things over. We have decided to purge our minds of all the excrement of useless and meaningless petty arguments and to increase our efforts, in order to make a little more progress in our quest for the attainment of enlightenment. When we have finally reached this goal, we will be full of gladness. We presume this will be well-founded, since we have diligently made strenuous endeavours in the practices of the Buddha teaching. Also, what we have accomplished is vast and abundant. | + | Now on this day, [[World]] Honoured One, we have been [[pondering]] things over. We have decided to purge our [[minds]] of all the excrement of useless and meaningless petty arguments and to increase our efforts, in order to make a little more progress in our quest for the [[attainment]] of [[enlightenment]]. When we have finally reached this goal, we will be full of gladness. We presume this will be well-founded, since we have diligently made strenuous endeavours in the practices of the [[Buddha]] [[teaching]]. Also, what we have accomplished is vast and abundant. |

| − | Naturally, the World Honoured One knew beforehand about our attachments, libidinal imaginings, and that we like the teachings of the individual vehicle (shōjō, hīnayāna). Until now, we have been left to our own devices, and we have not been noticed. We too wish to have a portion of the wealth that is the wisdom and vision of the Buddha. According to the Buddha, we have reached the stage of nirvana, as a culmination of our efforts. This is an enormous achievement. | + | Naturally, the [[World]] Honoured One knew beforehand about our [[attachments]], libidinal imaginings, and that we like the teachings of the [[individual vehicle]] (shōjō, [[hīnayāna]]). Until now, we have been left to our [[own]] devices, and we have not been noticed. We too wish to have a portion of the [[wealth]] that is the [[wisdom]] and [[vision]] of the [[Buddha]]. According to the [[Buddha]], we have reached the stage of [[nirvana]], as a culmination of our efforts. This is an enormous [[achievement]]. |

| − | When it comes to the universal vehicle (daijō, mahāyāna), we have neither the will nor the desire to look into it. Furthermore, on account of the four perceptive wisdoms of the Tathāgata that were revealed to the bodhisattvas – which are to open the perceptive wisdom of the Buddha that is within us, to demonstrate and explain its meaning, to make people know and understand that it is always present, and to lead them into a way of life in which this wisdom is applicable – we have neither the indefatigability nor the desire to go further. | + | When it comes to the [[universal]] [[vehicle]] ([[daijō]], [[mahāyāna]]), we have neither the will nor the [[desire]] to look into it. Furthermore, on account of the four perceptive [[wisdoms]] of the [[Tathāgata]] that were revealed to the [[bodhisattvas]] – which are to open the perceptive [[wisdom]] of the [[Buddha]] that is within us, to demonstrate and explain its meaning, to make [[people]] know and understand that it is always {{Wiki|present}}, and to lead them into a way of [[life]] in which this [[wisdom]] is applicable – we have neither the indefatigability nor the [[desire]] to go further. |

| − | Why should it be so? The Buddha knew that our minds were attached to the teachings of the individual vehicle (shōjō, hīnayāna), and he expounded the Dharma to us through the authority of the expedient means. Besides, we did not know that in reality we were children of the Buddha. Now, World Honoured One, we have come to understand that, with regard to the wisdom of the Buddha, it is completely devoid of any self-centred or self-seeking qualities. | + | Why should it be so? The [[Buddha]] knew that our [[minds]] were [[attached]] to the teachings of the [[individual vehicle]] (shōjō, [[hīnayāna]]), and he expounded the [[Dharma]] to us through the authority of the [[expedient means]]. Besides, we did not know that in [[reality]] we were children of the [[Buddha]]. Now, [[World]] Honoured One, we have come to understand that, with regard to the [[wisdom]] of the [[Buddha]], it is completely devoid of any self-centred or self-seeking qualities. |

| − | What is the reason for this? From the very beginning, even though we have been faithful followers of the Buddha, we have only appreciated the dharmas of the individual vehicle (shōjō, hīnayāna). If we were to set store by the universal vehicle (daijō, mahāyāna), the Buddha would then have expounded the universal vehicle (daijō, mahāyāna) for our benefit. | + | What is the [[reason]] for this? From the very beginning, even though we have been faithful followers of the [[Buddha]], we have only appreciated the [[dharmas]] of the [[individual vehicle]] (shōjō, [[hīnayāna]]). If we were to set store by the [[universal]] [[vehicle]] ([[daijō]], [[mahāyāna]]), the [[Buddha]] would then have expounded the [[universal]] [[vehicle]] ([[daijō]], [[mahāyāna]]) for our [[benefit]]. |

| − | Now, in this particular sutra, the Buddha only preaches the one vehicle to enlightenment. However, in the past and in front of all the bodhisattvas, he spoke of the faults of those people who exerted themselves to reach the highest stage of the individual vehicle (shōjō, hīnayāna) through listening to the Buddha, as well as other intellectual seekers (shōmon, shrāvaka), with regard to the vehicles to enlightenment for themselves. But, in fact, it is by means of the universal vehicle (daijō, mahāyāna) that the Buddha converts people towards enlightenment. This is the reason why we say that, even though we have no real mind or desire to seek anything else, it is because the universal wealth of the sovereign of the Dharma has spontaneously fallen into our hands. This is what all those who have faith in the teaching of the Buddha will obtain, but it is something we have already acquired. | + | Now, in this particular [[sutra]], the [[Buddha]] only preaches the one [[vehicle]] to [[enlightenment]]. However, in the {{Wiki|past}} and in front of all the [[bodhisattvas]], he spoke of the faults of those [[people]] who exerted themselves to reach the [[highest]] stage of the [[individual vehicle]] (shōjō, [[hīnayāna]]) through listening to the [[Buddha]], as well as other [[intellectual]] seekers ([[shōmon]], [[shrāvaka]]), with regard to the vehicles to [[enlightenment]] for themselves. But, in fact, it is by means of the [[universal]] [[vehicle]] ([[daijō]], [[mahāyāna]]) that the [[Buddha]] converts [[people]] towards [[enlightenment]]. This is the [[reason]] why we say that, even though we have no real [[mind]] or [[desire]] to seek anything else, it is because the [[universal]] [[wealth]] of the sovereign of the [[Dharma]] has spontaneously fallen into our hands. This is what all those who have [[faith]] in the [[teaching]] of the [[Buddha]] will obtain, but it is something we have already acquired. |

| − | There and then, Makakashō (Mahākāshyapa), wishing to reiterate these concepts, expressed them in the form of a metric hymn. | + | There and then, [[Makakashō]] ([[Mahākāshyapa]]), wishing to reiterate these [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]], expressed them in the [[form]] of a metric hymn. |

<poem> | <poem> | ||

We, this very day, | We, this very day, | ||

| − | hear the sounds of the Buddha teachings | + | hear the {{Wiki|sounds}} of the [[Buddha]] teachings |

so that we are exuberant | so that we are exuberant | ||

| − | and full of joy, | + | and full of [[joy]], |

on account of our receiving | on account of our receiving | ||

what we have never received before. | what we have never received before. | ||

| − | The Buddha himself states | + | The [[Buddha]] himself states |

| − | that intellectual seekers | + | that [[intellectual]] seekers |

| − | and those who listen to him (shōmon, shrāvaka) | + | and those who listen to him ([[shōmon]], [[shrāvaka]]) |

will also attain | will also attain | ||

| − | the fruition of Buddhahood (sabutsu), | + | the [[fruition]] of [[Buddhahood]] (sabutsu), |

| − | so that the accumulation | + | so that the [[accumulation]] |

| − | of unsurpassed treasures | + | of [[unsurpassed]] [[treasures]] |

has fallen into our hands, | has fallen into our hands, | ||

without our looking for it. | without our looking for it. | ||

| Line 181: | Line 181: | ||

| − | The fifth important point, which concerns the phrase, “so that the accumulation of unsurpassed treasures has spontaneously fallen into our hands, without our looking for it”. | + | The fifth important point, which concerns the [[phrase]], “so that the [[accumulation]] of [[unsurpassed]] [[treasures]] has spontaneously fallen into our hands, without our looking for it”. |

| − | The Oral Transmission on the Meaning of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Ongi Kuden) says that the word | + | The [[Oral Transmission]] on the Meaning of the [[Dharma]] [[Flower Sutra]] ([[Ongi Kuden]]) says that the [[word]] “[[unsurpassed]]” is charged with various levels of meaning and implication. For instance, when the teachings that came before the [[Buddha]] [[teaching]] and those outside of it are compared to those of the three collections of writings which are the [[sutras]], [[rules of monastic discipline]], and [[doctrinal]] treatises that comprise them, the teachings of the [[individual vehicle]] (sanzō-kyō) were considered to be [[unsurpassed]] in profundity. They were then surpassed by the interconnecting teachings (tsūgyō), which served as a bridge between the [[doctrines]] of the [[individual vehicle]] (shōjō, [[hīnayāna]]) and those of the [[universal]] [[vehicle]] ([[daijō]], [[mahāyāna]]). These were also [[thought]] of as being [[unsurpassed]] in profundity. However, those teachings were surpassed by the particular [[teaching]] that was different from the other three of the four kinds of [[teaching]] (bekkyō), which then became the [[doctrine]] that was [[unsurpassed]] in depth of meaning, but, nevertheless, was outdistanced by the all-inclusive [[teaching]] (engyō) that, in its turn, became the [[unsurpassed]] [[doctrine]] for its profundity. |

| − | Again, these all-inclusive teachings (engyō) that were expounded prior to the exposition of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō) were surpassed by the illumination of the all-inclusive doctrine of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō) itself. So, the all-inclusive teachings of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō) were doctrines that were yet unsurpassed in their profundity. Then again, the part of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō), in which the all-inclusive teachings are derived from the external events of the Buddha’s life and work (shakumon), was surpassed by the other half of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō), where the all-inclusive teachings are expounded from the viewpoint of the original archetypal state of existence. As a result, those teachings of the all-inclusive original archetypal state became those that were unsurpassed in their profundity. | + | Again, these all-inclusive teachings (engyō) that were expounded prior to the [[exposition]] of the [[Dharma]] [[Flower Sutra]] ([[Hokke-kyō]]) were surpassed by the [[illumination]] of the all-inclusive [[doctrine]] of the [[Dharma]] [[Flower Sutra]] ([[Hokke-kyō]]) itself. So, the all-inclusive teachings of the [[Dharma]] [[Flower Sutra]] ([[Hokke-kyō]]) were [[doctrines]] that were yet [[unsurpassed]] in their profundity. Then again, the part of the [[Dharma]] [[Flower Sutra]] ([[Hokke-kyō]]), in which the all-inclusive teachings are derived from the external events of the [[Buddha’s]] [[life]] and work ([[shakumon]]), was surpassed by the other half of the [[Dharma]] [[Flower Sutra]] ([[Hokke-kyō]]), where the all-inclusive teachings are expounded from the viewpoint of the original {{Wiki|archetypal}} [[state]] of [[existence]]. As a result, those teachings of the all-inclusive original {{Wiki|archetypal}} [[state]] became those that were [[unsurpassed]] in their profundity. |

| − | Again, the first thirteen chapters of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke-kyō) also had a doctrine that surpassed them. Those were supplanted by the Second Chapter on Expedient Means of the same sutra, as being unsurpassed in meaning. This is the chapter in which the Buddha Shākyamuni states that the Buddhas came into the realms of existence, in order to awaken in sentient beings the awareness of their Buddha natures and the wisdom that is inherent in it, including the real aspect of all dharmas. | + | Again, the first thirteen chapters of the [[Dharma]] [[Flower Sutra]] ([[Hokke-kyō]]) also had a [[doctrine]] that surpassed them. Those were supplanted by the Second [[Chapter]] on [[Expedient Means]] of the same [[sutra]], as being [[unsurpassed]] in meaning. This is the [[chapter]] in which the [[Buddha]] [[Shākyamuni]] states that the [[Buddhas]] came into the [[realms]] of [[existence]], in order to [[awaken]] in [[sentient beings]] the [[awareness]] of their [[Buddha]] natures and the [[wisdom]] that is [[inherent]] in it, including the real aspect of all [[dharmas]]. |

| − | However, the thirteenth chapter of the teachings of the original archetypal state supplanted the Chapter on Expedient Means, as being the teaching that is unsurpassed in profundity. But it is the “one chapter and two halves”, which are comprised of the second half of the Fifteenth Chapter on the Bodhisattvas who Swarm up out of the Earth, the whole of the Sixteenth Chapter on the Lifespan of the Tathāgata, and the first half of the Seventeenth Chapter on Discerning the Meritorious Virtues, which were then unsurpassed. | + | However, the thirteenth [[chapter]] of the teachings of the original {{Wiki|archetypal}} [[state]] supplanted the [[Chapter]] on [[Expedient Means]], as being the [[teaching]] that is [[unsurpassed]] in profundity. But it is the “one [[chapter]] and two halves”, which are comprised of the second half of the Fifteenth [[Chapter]] on the [[Bodhisattvas]] who Swarm up out of the [[Earth]], the whole of the Sixteenth [[Chapter]] on the [[Lifespan]] of the [[Tathāgata]], and the first half of the Seventeenth [[Chapter]] on Discerning the [[Meritorious]] [[Virtues]], which were then [[unsurpassed]]. |

| − | Again, out of the teachings that were propagated by the Universal Teacher Tendai (T’ien T’ai), the Universal Desistance from Troublesome Worries in order to See Clearly (Maka Shikan) became the teaching that was unsurpassed. Furthermore, the Textual Explanation of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke Mongu) and the Recondite Significance of the Dharma Flower Sutra (Hokke Gengi) also have teachings that transcend them. | + | Again, out of the teachings that were propagated by the [[Universal]] [[Teacher]] [[Tendai]] ([[T’ien T’ai]]), the [[Universal]] Desistance from Troublesome Worries in order to See Clearly (Maka [[Shikan]]) became the [[teaching]] that was [[unsurpassed]]. Furthermore, the Textual Explanation of the [[Dharma]] [[Flower Sutra]] (Hokke Mongu) and the Recondite Significance of the [[Dharma]] [[Flower Sutra]] (Hokke Gengi) also have teachings that transcend them. |

| − | Now, in the mind of Nichiren along with those that follow him, what is unsurpassed is Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō. This means that we return our lives and devote them to where the interdependence of cause, concomitancy and effecttakes place which is throughout the entirety of existence. [The implication of this concept is that we consecrate our lives to the essence of life itself.] Among all that which is unsurpassed, it is the highest summit of all. | + | Now, in the [[mind]] of [[Nichiren]] along with those that follow him, what is [[unsurpassed]] is [[Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō]]. This means that we return our [[lives]] and devote them to where the [[interdependence]] of [[cause]], concomitancy and effecttakes place which is throughout the entirety of [[existence]]. [The implication of this {{Wiki|concept}} is that we [[consecrate]] our [[lives]] to the [[essence]] of [[life]] itself.] Among all that which is [[unsurpassed]], it is the [[highest]] summit of all. |