Difference between revisions of "The Shurangama Sutra With Commentary by the Tripitaka Master Hsuan Hua: Volume 2"

(Created page with "{{DisplayImages|2518|2317|711|1902|2651|1694|3131|12|2486|1101|2277|2073|3323|1511|3220|1864|2182|3498|1325|447|1424|3566|2371|2468|1020|64|592|2310|428|986|70|1001|654|3133|2...") |

m (Text replacement - "Thus Come" to "Thus Come") |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{DisplayImages|2518|2317|711|1902|2651|1694|3131|12|2486|1101|2277|2073|3323|1511|3220|1864|2182|3498|1325|447|1424|3566|2371|2468|1020|64|592|2310|428|986|70|1001|654|3133|250|629|3494|1237|1964|2610|3398|1173|2790|1734|1686|1144|2290|2038|1943|1604|365|132|2488|1004|2894|1994|2087|631|521|2574|1513|469|2030|1636|3246|2603|1917|1617|1109|406|2178|1190|1777|634|2449|713|139|2392|1989|2045|3224|1467|1341|968|858|3290|2259|3491|1613|134|969|1946|2904|460|2752|367|3388|467|901|1991|2719|2670|156|1761|3611|1810|820|3241|195|866|2192|2426|2132|376|14|1063|1572|1136|2119|1339|993|1684|581|2450|827|810|3463|1297|3245|484|1285|2471|2501|918|2314|3459|818|3609|603|2312|1195|2423|797|2586|3414|474|3528|1447|255|1176|3378|914|1710|1563|2026|3425|1541|560|115|1433|931|1980|1011|1578|3331|768|1251|2060|555|628|2158|2409|1287|429|1139|3317|2244|1915|550|1328|1446|1495|3603|899|119|887|3555|281|1783|2760|627|2395|527|444|559|3168|3222|890|1113|1436|2497|345|2287|289|151|1464|2357|1151|572|2380|3599|891|3079|1274|1975|2276|1317|3461|2756|3083|1309|323|2831|2149|2930|2265|3636|1284|2681|2804|1405|2944|197|1282|2077|1551|1156|2193|1901|2391|2247|940|1461|3393|2633|2535|308|975|1039|2105|2326|1969|161|1452|2705|3117|3624|1671 | + | {{DisplayImages|2518|2317|711|1902|2651|1694|3131|12|2486|1101|2277|2073|3323|1511|3220|1864|2182|3498|1325|447|1424|3566|2371|2468|1020|64|592|2310|428|986|70|1001|654|3133|250|629|3494|1237|1964|2610|3398|1173|2790|1734|1686|1144|2290|2038|1943|1604|365|132|2488|1004|2894|1994|2087|631|521|2574|1513|469|2030|1636|3246|2603|1917|1617|1109|406|2178|1190|1777|634|2449|713|139|2392|1989|2045|3224|1467|1341|968|858|3290|2259|3491|1613|134|969|1946|2904|460|2752|367|3388|467|901|1991|2719|2670|156|1761|3611|1810|820|3241|195|866|2192|2426|2132|376|14|1063|1572|1136|2119|1339|993|1684|581|2450|827|810|3463|1297|3245|484|1285|2471|2501|918|2314|3459|818|3609|603|2312|1195|2423|797|2586|3414|474|3528|1447|255|1176|3378|914|1710|1563|2026|3425|1541|560|115|1433|931|1980|1011|1578|3331|768|1251|2060|555|628|2158|2409|1287|429|1139|3317|2244|1915|550|1328|1446|1495|3603|899|119|887|3555|281|1783|2760|627|2395|527|444|559|3168|3222|890|1113|1436|2497|345|2287|289|151|1464|2357|1151|572|2380|3599|891|3079|1274|1975|2276|1317|3461|2756|3083|1309|323|2831|2149|2930|2265|3636|1284|2681|2804|1405|2944|197|1282|2077|1551|1156|2193|1901|2391|2247|940|1461|3393|2633|2535|308|975|1039|2105|2326|1969|161|1452|2705|3117|3624|1671}} |

{{Centre|<big><big>The Shurangama Sutra<br/> | {{Centre|<big><big>The Shurangama Sutra<br/> | ||

With Commentary by the Tripitaka Master Hsuan Hua<br/></big></big> | With Commentary by the Tripitaka Master Hsuan Hua<br/></big></big> | ||

<big>Volume 2<br/></big>}} <br/><br/> | <big>Volume 2<br/></big>}} <br/><br/> | ||

| − | ==CHAPTER 1: The Seeing Nature == | + | ==CHAPTER 1: The [[Seeing]] [[Nature]] == |

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | K2 He displays the true nature. | + | K2 He displays the [[true nature]]. |

| − | L1 He divides the nature of the organ and points straight to the true mind. | + | L1 He divides the [[nature]] of the {{Wiki|organ}} and points straight to the true [[mind]]. |

M1 He uses the false to reveal the true. | M1 He uses the false to reveal the true. | ||

| − | N1 He shows that the seeing is the mind. | + | N1 He shows that the [[seeing]] is the [[mind]]. |

| − | O1 He exhibits a dharma analogy. | + | O1 He exhibits a [[dharma]] analogy. |

</poem> | </poem> | ||

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | "Ananda, you have told me that you saw my fist of bright light. How did it take the form of a fist? How did the fist become bright? By what means could you see it?” | + | "[[Ananda]], you have told me that you saw my fist of bright light. How did it take the [[form]] of a fist? How did the fist become bright? By what means could you see it?” |

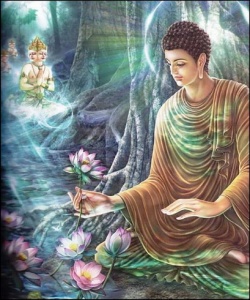

| − | Ananda replied, “The body of the Buddha is born of purity and cleanness, and, therefore, it assumes the color of Jambu River gold with deep red hues. Hence, it shone as brilliant and dazzling as a precious mountain. It was actually my eyes that saw the Buddha bend his five-wheeled fingers to form a fist which was shown to all of us.” | + | [[Ananda]] replied, “The [[body]] of the [[Buddha]] is born of [[purity]] and [[cleanness]], and, therefore, it assumes the {{Wiki|color}} of [[Jambu]] [[River]] {{Wiki|gold}} with deep red hues. Hence, it shone as brilliant and dazzling as a [[precious]] mountain. It was actually my [[eyes]] that saw the [[Buddha]] bend his five-wheeled fingers to [[form]] a fist which was shown to all of us.” |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | The Buddha called again to Ananda: Ananda, you have told me that you saw my fist of bright light. How did it take the form of a fist? How did the fist become bright? Tell me why my fist had light. By what means could you see it? What did you use to see it? | + | The [[Buddha]] called again to [[Ananda]]: [[Ananda]], you have told me that you saw my fist of bright light. How did it take the [[form]] of a fist? How did the fist become bright? Tell me why my fist had light. By what means could you see it? What did you use to see it? |

| − | Ananda replied: The body of the Buddha is born of purity and cleanness, and, therefore, it assumes the color of Jambu River gold with deep red hues. Hence, it shone as brilliant and dazzling as a precious mountain. The Buddha’s entire body is the color of Jambu River gold. The Jambu River is located in southern Jambudvipa. The gold found in this river has a slightly reddish cast to it. In southern Jambudvipa there is a species of tree called the Jambu, and it is perhaps the stems of its leaves which turn to gold when they fall into the water. This kind of gold is much heavier than ordinary gold, and the Buddha’s body is likened to it; like the color of Jambu River gold, the color of the Buddha’s body is a combination of gold and red. | + | [[Ananda]] replied: The [[body]] of the [[Buddha]] is born of [[purity]] and [[cleanness]], and, therefore, it assumes the {{Wiki|color}} of [[Jambu]] [[River]] {{Wiki|gold}} with deep red hues. Hence, it shone as brilliant and dazzling as a [[precious]] mountain. The [[Buddha’s]] entire [[body]] is the {{Wiki|color}} of [[Jambu]] [[River]] {{Wiki|gold}}. The [[Jambu]] [[River]] is located in southern [[Jambudvipa]]. The {{Wiki|gold}} found in this [[river]] has a slightly reddish cast to it. In southern [[Jambudvipa]] there is a species of [[tree]] called the [[Jambu]], and it is perhaps the stems of its leaves which turn to {{Wiki|gold}} when they fall into the [[water]]. This kind of {{Wiki|gold}} is much heavier than ordinary {{Wiki|gold}}, and the [[Buddha’s]] [[body]] is likened to it; like the {{Wiki|color}} of [[Jambu]] [[River]] {{Wiki|gold}}, the {{Wiki|color}} of the [[Buddha’s]] [[body]] is a combination of {{Wiki|gold}} and red. |

| − | A body with that kind of appearance is produced from purity and therefore has light. The light exists because of that purity. | + | A [[body]] with that kind of [[appearance]] is produced from [[purity]] and therefore has light. The light [[exists]] because of that [[purity]]. |

| − | ”It was actually my eyes that saw,” Ananda says. “I really used my eyes to see it. The five-wheeled fingers were clenched as they were shown to people, and that is what made the appearance of a fist.” | + | ”It was actually my [[eyes]] that saw,” [[Ananda]] says. “I really used my [[eyes]] to see it. The five-wheeled fingers were clenched as they were shown to [[people]], and that is what made the [[appearance]] of a fist.” |

O2 He states the dharma-analogy and investigates it. | O2 He states the dharma-analogy and investigates it. | ||

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | The Buddha told Ananda, “Today the Tathagata will tell you truly that all those with wisdom are able to achieve enlightenment through the use of examples. | + | The [[Buddha]] told [[Ananda]], “Today the [[Tathagata]] will tell you truly that all those with [[wisdom]] are able to achieve [[enlightenment]] through the use of examples. |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | The Buddha told Ananda, “Today the Tathagata will tell you truly. Now I am going to tell you the absolute truth. Are you listening? All those with wisdom are able to achieve enlightenment through the use of examples. People who are wise like to use examples in order to attain enlightenment, because if you really have wisdom, you will understand ten things when you are told one thing. I say something one way and you deduce perhaps ten or a hundred things from it. That is to have genuine wisdom.” Here “those with | + | The [[Buddha]] told [[Ananda]], “Today the [[Tathagata]] will tell you truly. Now I am going to tell you the [[absolute truth]]. Are you listening? All those with [[wisdom]] are able to achieve [[enlightenment]] through the use of examples. [[People]] who are [[wise]] like to use examples in order to attain [[enlightenment]], because if you really have [[wisdom]], you will understand ten things when you are told one thing. I say something one way and you deduce perhaps ten or a hundred things from it. That is to have genuine [[wisdom]].” Here “those with [[wisdom]]” does not mean [[people]] with genuine [[wisdom]], though, but [[people]] with ordinary [[wisdom]] which is neither {{Wiki|superior}} nor {{Wiki|inferior}}. Such [[people]] can become [[enlightened]] through the use of analogies. But if stupid [[people]] who lack [[wisdom]] are given an analogy, they don’t understand, and they say, “What does that mean?” |

| − | ===Seeing Is the Mind=== | + | ===[[Seeing]] Is the [[Mind]]=== |

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | + | “[[Ananda]], take, for example, my fist: if I didn’t have a hand, I couldn’t make a fist. If you didn’t have [[eyes]], you couldn’t see. If you apply the example of my fist to the case of your [[eyes]], is the [[idea]] the same?” | |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | "Ananda, take, for example, my fist: if I didn’t have a hand, I couldn’t make a fist. By the same token, if you didn’t have eyes, you couldn’t see. If you apply the example of my fist to the case of your eyes, is the idea the same? Are we talking about the same thing or not?” the Buddha asks Ananda. | + | "[[Ananda]], take, for example, my fist: if I didn’t have a hand, I couldn’t make a fist. By the same token, if you didn’t have [[eyes]], you couldn’t see. If you apply the example of my fist to the case of your [[eyes]], is the [[idea]] the same? Are we talking about the same thing or not?” the [[Buddha]] asks [[Ananda]]. |

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | Ananda said, “Yes, World Honored One. Since I can’t see without my eyes, if one applies the example of the Buddha’s fist to the case of your eyes, the idea is the same.” | + | [[Ananda]] said, “Yes, [[World Honored One]]. Since I can’t see without my [[eyes]], if one applies the example of the [[Buddha’s]] fist to the case of your [[eyes]], the [[idea]] is the same.” |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | Ananda didn’t take time to cogitate over it. He isn’t thinking now. Ananda said, “Yes, World Honored One. Since I can’t see without my eyes, if one applies the example of the Buddha’s fist to the case of your eyes, the idea is the same. Yes, Buddha, if you compare these two cases, the idea is the same.” | + | [[Ananda]] didn’t take [[time]] to cogitate over it. He isn’t [[thinking]] now. [[Ananda]] said, “Yes, [[World Honored One]]. Since I can’t see without my [[eyes]], if one applies the example of the [[Buddha’s]] fist to the case of your [[eyes]], the [[idea]] is the same. Yes, [[Buddha]], if you compare these two cases, the [[idea]] is the same.” |

| − | O3 He makes clear that without eyes there is still seeing. | + | O3 He makes clear that without [[eyes]] there is still [[seeing]]. |

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | The Buddha said to Ananda, “You say it is the same, but that is not right. Why? If a person has no hand, his fist is gone forever. But one who is without eyes is not entirely devoid of sight. | + | The [[Buddha]] said to [[Ananda]], “You say it is the same, but that is not right. Why? If a [[person]] has no hand, his fist is gone forever. But one who is without [[eyes]] is not entirely devoid of [[sight]]. |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | Here the Buddha criticizes Ananda, telling him his idea is incorrect. The Buddha said to Ananda, “You say it is the same, but that is not right. You say the example is the same in both cases. No. Why? If a person has no hand, his fist is gone forever. If someone doesn’t have a hand, he doesn’t have a fist either. But one who is without eyes is not entirely devoid of sight. But with someone else who has no eyes it is not the case that he cannot see anything. He can see.” People without eyes can see. Do you believe that? | + | Here the [[Buddha]] criticizes [[Ananda]], telling him his [[idea]] is incorrect. The [[Buddha]] said to [[Ananda]], “You say it is the same, but that is not right. You say the example is the same in both cases. No. Why? If a [[person]] has no hand, his fist is gone forever. If someone doesn’t have a hand, he doesn’t have a fist either. But one who is without [[eyes]] is not entirely devoid of [[sight]]. But with someone else who has no [[eyes]] it is not the case that he cannot see anything. He can see.” [[People]] without [[eyes]] can see. Do you believe that? |

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | "For what reason? Try consulting a blind man on the street: ‘What do you see?’ | + | "For what [[reason]]? Try consulting a blind man on the street: ‘What do you see?’ |

| − | "Any blind man will certainly answer, ‘Now I see only black in front of my eyes. Nothing else meets my gaze.’ | + | "Any blind man will certainly answer, ‘Now I see only black in front of my [[eyes]]. Nothing else meets my gaze.’ |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | For what reason? Why do I say that? Try consulting a blind man on the street: “What do you see?” Go out to the market and ask a blind man what he sees. Any blind man will certainly answer, “Now I see only black in front of my eyes. Nothing else meets my gaze.” He’ll say that he doesn’t see anything but blackness. | + | For what [[reason]]? Why do I say that? Try consulting a blind man on the street: “What do you see?” Go out to the market and ask a blind man what he sees. Any blind man will certainly answer, “Now I see only black in front of my [[eyes]]. Nothing else meets my gaze.” He’ll say that he doesn’t see anything but blackness. |

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | "The meaning is apparent: if he sees blackness in front of him, how would his seeing be considered ‘lost’?” | + | "The meaning is apparent: if he sees blackness in front of him, how would his [[seeing]] be considered ‘lost’?” |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | The meaning is apparent: if you get the idea, if you take a look at what it means, if he sees blackness in front of him, how could his seeing be considered “lost”? If you see blackness before you, your ability to see is not lost; it neither increases nor decreases. | + | The meaning is apparent: if you get the [[idea]], if you take a look at what it means, if he sees blackness in front of him, how could his [[seeing]] be considered “lost”? If you see blackness before you, your ability to see is not lost; it neither increases nor {{Wiki|decreases}}. |

| − | O4 He makes clear that seeing darkness is seeing. | + | O4 He makes clear that [[seeing]] {{Wiki|darkness}} is [[seeing]]. |

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | Ananda said, “The only thing blind people see in front of their eyes is blackness. How can that be seeing?” | + | [[Ananda]] said, “The only thing blind [[people]] see in front of their [[eyes]] is blackness. How can that be [[seeing]]?” |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | Ananda reiterates the Buddha’s example: a blind person has no use of his eyes and so sees only darkness. But according to Ananda, this seeing of darkness is not really seeing. Ananda is saying that someone without the use of his eyes cannot see. “Why do you say the blind man sees?” he asks the Buddha. | + | [[Ananda]] reiterates the [[Buddha’s]] example: a blind [[person]] has no use of his [[eyes]] and so sees only {{Wiki|darkness}}. But according to [[Ananda]], this [[seeing]] of {{Wiki|darkness}} is not really [[seeing]]. [[Ananda]] is saying that someone without the use of his [[eyes]] cannot see. “Why do you say the blind man sees?” he asks the [[Buddha]]. |

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | The Buddha said to Ananda, “Is there any difference between the blackness seen by blind people, who do not have the use of their eyes, and the blackness seen by someone who has the use of his eyes when he is in a dark room?” | + | The [[Buddha]] said to [[Ananda]], “Is there any difference between the blackness seen by blind [[people]], who do not have the use of their [[eyes]], and the blackness seen by someone who has the use of his [[eyes]] when he is in a dark room?” |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | Is the darkness that sighted people see when they are in a dark house that is without the light of sun, moon, or lamps any different from the darkness seen by blind people? If a blind person and a person who has sight are together in a dark room, are the two blacks they see distinguishable? | + | Is the {{Wiki|darkness}} that sighted [[people]] see when they are in a dark house that is without the light of {{Wiki|sun}}, [[moon]], or lamps any different from the {{Wiki|darkness}} seen by blind [[people]]? If a blind [[person]] and a [[person]] who has [[sight]] are together in a dark room, are the two blacks they see distinguishable? |

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | "So it is, World Honored One. Between the two kinds of blackness, that seen by the person in a dark room and that seen by the blind, there is no difference.” | + | "So it is, [[World Honored One]]. Between the two kinds of blackness, that seen by the [[person]] in a dark room and that seen by the blind, there is no difference.” |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | Ananda answers the World Honored One’s question, “So it is. Yes, Buddha. Between the two kinds of blackness, that seen by the person in a dark room - by the sighted person - and that seen by the blind, there is no difference. The two kinds of blackness are the same.” | + | [[Ananda]] answers the [[World]] Honored One’s question, “So it is. Yes, [[Buddha]]. Between the two kinds of blackness, that seen by the [[person]] in a dark room - by the sighted [[person]] - and that seen by the blind, there is no difference. The two kinds of blackness are the same.” |

| − | "Fine,” said the Buddha. “Yes.” | + | "Fine,” said the [[Buddha]]. “Yes.” |

| − | O5 He states that the eye’s seeing is the mind. | + | O5 He states that the eye’s [[seeing]] is the [[mind]]. |

| − | P1 He points out the fault in the eye’s seeing. | + | P1 He points out the fault in the eye’s [[seeing]]. |

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | "Ananda, if the person without the use of his eyes who sees only blackness were suddenly to regain his sight and see all kinds of forms, and you say it is his eyes which see, then when the person in a dark room who sees only blackness suddenly sees all kinds of forms because a lamp is lit, you should say it is the lamp which sees. | + | "[[Ananda]], if the [[person]] without the use of his [[eyes]] who sees only blackness were suddenly to regain his [[sight]] and see all kinds of [[forms]], and you say it is his [[eyes]] which see, then when the [[person]] in a dark room who sees only blackness suddenly sees all kinds of [[forms]] because a [[lamp]] is lit, you should say it is the [[lamp]] which sees. |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | The Buddha said to Ananda: Ananda, if the person without the use of his eyes who sees only blackness were suddenly to regain his sight and see all kinds of | + | The [[Buddha]] said to [[Ananda]]: [[Ananda]], if the [[person]] without the use of his [[eyes]] who sees only blackness were suddenly to regain his [[sight]] and see all kinds of [[forms]]… you say that there is no difference between the two kinds of blackness. But what if the blind [[person]] in our example were suddenly to regain his [[sight]] so that his [[eyes]] could see everything in every [[direction]]? You say it is his [[eyes]] which see. This is your argument. But what about the case when the [[person]] in a dark room who sees only blackness suddenly sees all kinds of [[forms]] because a [[lamp]] is lit? The sighted [[person]] in a dark room also sees blackness, but once a [[lamp]] is lit, he too can see everything. Given your argument, you should say it is the [[lamp]] which sees. |

| − | Why does the Buddha say that? People in a dark room cannot see, but when a lamp is lit, they can see. People who don’t have the use of their eyes cannot see, but if they regain their sight then they can see again. If when that person who cannot see suddenly sees because he regains his sight, then when the person in the dark room sees because of the lamp, that should be called the lamp’s seeing. “Is that right?” the Buddha asks. | + | Why does the [[Buddha]] say that? [[People]] in a dark room cannot see, but when a [[lamp]] is lit, they can see. [[People]] who don’t have the use of their [[eyes]] cannot see, but if they regain their [[sight]] then they can see again. If when that [[person]] who cannot see suddenly sees because he regains his [[sight]], then when the [[person]] in the dark room sees because of the [[lamp]], that should be called the lamp’s [[seeing]]. “Is that right?” the [[Buddha]] asks. |

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | “If it is a case of the lamp seeing, it would be a lamp endowed with sight - which couldn’t be called a lamp. And if the lamp were to do the seeing, how would you be involved? | + | “If it is a case of the [[lamp]] [[seeing]], it would be a [[lamp]] endowed with [[sight]] - which couldn’t be called a [[lamp]]. And if the [[lamp]] were to do the [[seeing]], how would you be involved? |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | If it really were the case that the lamp could see and do the looking, then it wouldn’t have anything to do with you. | + | If it really were the case that the [[lamp]] could see and do the looking, then it wouldn’t have anything to do with you. |

| − | P2 He concludes that in actual fact it is the mind that sees. | + | P2 He concludes that in actual fact it is the [[mind]] that sees. |

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | “Therefore you should know that while the lamp can reveal the forms, it is the eyes, not the lamp, that do the seeing. And while the eyes can reveal the forms, the seeing-nature comes from the mind, not the eyes.” | + | “Therefore you should know that while the [[lamp]] can reveal the [[forms]], it is the [[eyes]], not the [[lamp]], that do the [[seeing]]. And while the [[eyes]] can reveal the [[forms]], the seeing-nature comes from the [[mind]], not the [[eyes]].” |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | Therefore you should know that while the lamp can reveal the forms, it is the eyes, not the lamp, that do the seeing. The lamp allows the shapes to appear, but it is the eyes that see the shapes. By the same token, while the eyes can reveal the forms, the seeing-nature comes from the mind, not the eyes. We are now looking into the first or the ten manifestations of seeing. The first of the ten shows the seeing of the mind, not of the eyes. | + | Therefore you should know that while the [[lamp]] can reveal the [[forms]], it is the [[eyes]], not the [[lamp]], that do the [[seeing]]. The [[lamp]] allows the shapes to appear, but it is the [[eyes]] that see the shapes. By the same token, while the [[eyes]] can reveal the [[forms]], the seeing-nature comes from the [[mind]], not the [[eyes]]. We are now looking into the first or the ten [[manifestations]] of [[seeing]]. The first of the ten shows the [[seeing]] of the [[mind]], not of the [[eyes]]. |

</poem> | </poem> | ||

| − | ===Seeing Does Not Move=== | + | ===[[Seeing]] Does Not Move=== |

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | N2 He shows that the seeing does not move. | + | N2 He shows that the [[seeing]] does not move. |

| − | O1 Discussion of the assembly’s hope for instruction. | + | O1 [[Discussion]] of the assembly’s {{Wiki|hope}} for instruction. |

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | Although Ananda and everyone in the great assembly had heard what was said, their minds had not yet understood, and so they remained silent. Hoping to hear more of the gentle sounds of the Tathagata’s teaching, they put their palms together, purified their minds, and stood waiting for the Tathagata’s compassionate instruction. | + | Although [[Ananda]] and everyone in the [[great assembly]] had heard what was said, their [[minds]] had not yet understood, and so they remained [[silent]]. Hoping to hear more of the gentle {{Wiki|sounds}} of the [[Tathagata’s]] [[teaching]], they put their palms together, [[purified]] their [[minds]], and stood waiting for the [[Tathagata’s]] [[compassionate]] instruction. |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | Although Ananda and everyone in the great assembly had heard what was said, their minds had not yet understood, and so they remained silent. Ananda and everyone else there closed their mouths and didn’t say anything. Why weren’t they talking? They were thinking, “Oh? My eyes can’t see things? Oh? My mind sees? You may say that isn’t true, but the Buddha has explained it this way. If you say it is true, why haven’t I ever understood it to be this way before?” That’s what they were thinking, because they hadn’t yet understood. Their minds had not yet opened and become enlightened. Hoping to hear more of the gentle sounds of the Tathagata’s teaching - they were thinking, “I hope the Buddha will have a compassionate heart and talk to me.” They put their palms together. Why did they put their palms together? It represents their single-mindedness. They were of one mind, not two. When your hands are apart, it is said you have ten minds, and when your palms are together, it is said you have one mind, because when your palms go together, your mind comes together and becomes one. Purified their minds. Clear out your mind. Clear your heart. Don’t put too much garbage in your head. Take the garbage that is in there and get rid of it. And stood waiting for the Tathagata’s compassionate instruction. They stood waiting for the Buddha’s compassionate words to help them understand better, so they could become enlightened and not be so confused. | + | Although [[Ananda]] and everyone in the [[great assembly]] had heard what was said, their [[minds]] had not yet understood, and so they remained [[silent]]. [[Ananda]] and everyone else there closed their mouths and didn’t say anything. Why weren’t they talking? They were [[thinking]], “Oh? My [[eyes]] can’t see things? Oh? My [[mind]] sees? You may say that isn’t true, but the [[Buddha]] has explained it this way. If you say it is true, why haven’t I ever understood it to be this way before?” That’s what they were [[thinking]], because they hadn’t yet understood. Their [[minds]] had not yet opened and become [[enlightened]]. Hoping to hear more of the gentle {{Wiki|sounds}} of the [[Tathagata’s]] [[teaching]] - they were [[thinking]], “I {{Wiki|hope}} the [[Buddha]] will have a [[compassionate]] [[heart]] and talk to me.” They put their palms together. Why did they put their palms together? It represents their single-mindedness. They were of one [[mind]], not two. When your hands are apart, it is said you have ten [[minds]], and when your palms are together, it is said you have one [[mind]], because when your palms go together, your [[mind]] comes together and becomes one. [[Purified]] their [[minds]]. Clear out your [[mind]]. Clear your [[heart]]. Don’t put too much garbage in your head. Take the garbage that is in there and get rid of it. And stood waiting for the [[Tathagata’s]] [[compassionate]] instruction. They stood waiting for the [[Buddha’s]] [[compassionate]] words to help them understand better, so they could become [[enlightened]] and not be so confused. |

O2 He determines the guest and dust. | O2 He determines the guest and dust. | ||

| − | P1 The Thus Come One asks about the ultimate source of enlightenment. | + | P1 The [[Thus Come One]] asks about the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] source of [[enlightenment]]. |

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | Then the World Honored One extended his tula-cotton webbed bright hand, opened his five-wheeled fingers, and told Ananda and the great assembly, “When I first accomplished the Way I went to the Deer Park, and for the sake of Ajnatakaundinya and all five of the bhikshus, as well as for you of the fourfold assembly, I said, ‘It is because living beings are impeded by guest-dust and affliction that they do not realize Bodhi or become Arhats.’ At that time, what caused you who have now realized the holy fruit to become enlightened?” | + | Then the [[World Honored One]] extended his tula-cotton webbed bright hand, opened his five-wheeled fingers, and told [[Ananda]] and the [[great assembly]], “When I first accomplished the Way I went to the [[Deer Park]], and for the sake of [[Ajnatakaundinya]] and all five of the [[bhikshus]], as well as for you of the fourfold assembly, I said, ‘It is because [[living beings]] are impeded by guest-dust and [[affliction]] that they do not realize [[Bodhi]] or become [[Arhats]].’ At that [[time]], what [[caused]] you who have now [[realized]] the {{Wiki|holy}} fruit to become [[enlightened]]?” |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

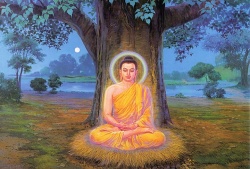

| − | Then, while those in the assembly stood waiting to receive the Buddha’s compassionate teaching and transforming, the World Honored One, Shakyamuni Buddha, extended his tula-cotton webbed bright hand, opened his five-wheeled fingers. On the Buddha’s hand is the hallmark of the thousand-spoked wheel. His hand is extremely soft, like the finest cotton, and it is webbed and luminous. He told Ananda and the great assembly: When I first accomplished the Way. One evening, on the eighth day of the twelfth month, while sitting under the Bodhi tree, he saw a star and awakened to perfect the Way. I went to the Deer Park. This is a vast park devoted exclusively to raising deer. How did that come about? It all began limitless kalpas ago when Shakyamuni Buddha was a deer, the leader of a herd of 500. And guess who else was there? Devadatta, who was also a deer king with a following of 500 deer. In the later life when the Buddha realized Buddhahood, Devadatta became the Buddha’s jealous cousin and tried to kill him. But in that earlier life when both were deer kings, there was a king among the people who used a lot of manpower and machinery to corral vast numbers of wild animals into a certain area. He planned to hunt them all down and kill them on the grounds that there were too many wild animals. So then Shakyamuni Buddha, in the form he had taken of a deer king had a meeting with the deer king Devadatta. They said to each other, “We should save the lives of our retinue. We shouldn’t let the king kill us all. How can we save ourselves? Let’s go talk it over with the king and petition him not to kill us off.” Although they were deer, they could speak the language of people. So the two deer went to see the king, and when they encountered the armed guard at the gates they said in a commanding tone, “We would like an appointment with the king. Can you deliver our message?” When the guard heard that the deer could speak the human language, he went to repeat their message to the king. | + | Then, while those in the assembly stood waiting to receive the [[Buddha’s]] [[compassionate]] [[teaching]] and [[transforming]], the [[World Honored One]], [[Shakyamuni Buddha]], extended his tula-cotton webbed bright hand, opened his five-wheeled fingers. On the [[Buddha’s]] hand is the hallmark of the thousand-spoked [[wheel]]. His hand is extremely soft, like the finest cotton, and it is webbed and {{Wiki|luminous}}. He told [[Ananda]] and the [[great assembly]]: When I first accomplished the Way. One evening, on the eighth day of the twelfth month, while sitting under the [[Bodhi tree]], he saw a star and [[awakened]] to perfect the Way. I went to the [[Deer Park]]. This is a vast park devoted exclusively to raising {{Wiki|deer}}. How did that come about? It all began limitless [[kalpas]] ago when [[Shakyamuni Buddha]] was a {{Wiki|deer}}, the leader of a herd of 500. And guess who else was there? [[Devadatta]], who was also a {{Wiki|deer}} [[king]] with a following of 500 {{Wiki|deer}}. In the later [[life]] when the [[Buddha]] [[realized]] [[Buddhahood]], [[Devadatta]] became the [[Buddha’s]] [[jealous]] cousin and tried to kill him. But in that earlier [[life]] when both were {{Wiki|deer}} [[kings]], there was a [[king]] among the [[people]] who used a lot of manpower and machinery to corral vast numbers of wild [[animals]] into a certain area. He planned to hunt them all down and kill them on the grounds that there were too many wild [[animals]]. So then [[Shakyamuni Buddha]], in the [[form]] he had taken of a {{Wiki|deer}} [[king]] had a meeting with the {{Wiki|deer}} [[king]] [[Devadatta]]. They said to each other, “We should save the [[lives]] of our retinue. We shouldn’t let the [[king]] kill us all. How can we save ourselves? Let’s go talk it over with the [[king]] and petition him not to kill us off.” Although they were {{Wiki|deer}}, they could speak the [[language]] of [[people]]. So the two {{Wiki|deer}} went to see the [[king]], and when they encountered the armed guard at the gates they said in a commanding tone, “We would like an appointment with the [[king]]. Can you deliver our message?” When the guard heard that the {{Wiki|deer}} could speak the [[human]] [[language]], he went to repeat their message to the [[king]]. |

| − | The king also found it strange to hear that deer could talk, and he agreed to an audience with them so they could state their petition. The two deer kings went before the king and said, “We are deer. Every day you kill seven or eight of us - more than you can possibly eat in a single day. What cannot be eaten is left to spoil. Wouldn’t it be better if we did it this way: every day we will take turns supplying you with one deer, and in that way you can have fresh venison every day without killing us all off at once. If you use this method, your supply of venison will never run out. Several hundred years from now there will still be venison to eat.” | + | The [[king]] also found it strange to hear that {{Wiki|deer}} could talk, and he agreed to an audience with them so they could state their petition. The two {{Wiki|deer}} [[kings]] went before the [[king]] and said, “We are {{Wiki|deer}}. Every day you kill seven or eight of us - more than you can possibly eat in a single day. What cannot be eaten is left to spoil. Wouldn’t it be better if we did it this way: every day we will take turns supplying you with one {{Wiki|deer}}, and in that way you can have fresh {{Wiki|venison}} every day without killing us all off at once. If you use this method, your supply of {{Wiki|venison}} will never run out. Several hundred years from now there will still be {{Wiki|venison}} to eat.” |

| − | Because he saw the sense in their petition, and because the deer could speak, the king was moved to grant their request. So each of the deer kings, on alternate days, sent the king a deer. Now one day it happened that it was the turn of a pregnant doe in Devadatta’s herd to go sacrifice herself to the king. Her fawn was heavy in her belly and would probably be born in a day or so. So she pleaded with the deer king Devadatta, “Can you send someone in my place today, and then after the fawn is born I will go to the king and sacrifice myself?” | + | Because he saw the [[sense]] in their petition, and because the {{Wiki|deer}} could speak, the [[king]] was moved to grant their request. So each of the {{Wiki|deer}} [[kings]], on alternate days, sent the [[king]] a {{Wiki|deer}}. Now one day it happened that it was the turn of a {{Wiki|pregnant}} doe in [[Devadatta’s]] herd to go {{Wiki|sacrifice}} herself to the [[king]]. Her fawn was heavy in her belly and would probably be born in a day or so. So she pleaded with the {{Wiki|deer}} [[king]] [[Devadatta]], “Can you send someone in my place today, and then after the fawn is born I will go to the [[king]] and {{Wiki|sacrifice}} myself?” |

| − | Devadatta replied, “Impossible. It is your turn, and you must go. There is no politeness in this matter. You don’t want to die. Who does? Not one of the deer want to go to their death. You want to live a few more days now that it has come around to your turn, but that is impossible.” | + | [[Devadatta]] replied, “Impossible. It is your turn, and you must go. There is no politeness in this {{Wiki|matter}}. You don’t want to [[die]]. Who does? Not one of the {{Wiki|deer}} want to go to their [[death]]. You want to live a few more days now that it has come around to your turn, but that is impossible.” |

| − | The pregnant doe’s eyes brimmed with tears and she went to talk to the deer king who was to become Shakyamuni Buddha. Although she didn’t belong to his herd, she went to plead with him and ask if he could work out a temporary exchange so she could live a few more days until her fawn was born. As he considered her request, Shakyamuni Buddha realized that not one of his 500 deer would want to go in her place. However, the Buddha said to her, “Fine. You stay in my herd; you don’t need to go.” Then the deer king Shakyamuni Buddha went himself to be sacrificed in her place. | + | The {{Wiki|pregnant}} doe’s [[eyes]] brimmed with {{Wiki|tears}} and she went to talk to the {{Wiki|deer}} [[king]] who was to become [[Shakyamuni Buddha]]. Although she didn’t belong to his herd, she went to plead with him and ask if he could work out a temporary exchange so she could live a few more days until her fawn was born. As he considered her request, [[Shakyamuni Buddha]] [[realized]] that not one of his 500 {{Wiki|deer}} would want to go in her place. However, the [[Buddha]] said to her, “Fine. You stay in my herd; you don’t need to go.” Then the {{Wiki|deer}} [[king]] [[Shakyamuni Buddha]] went himself to be sacrificed in her place. |

| − | The king asked him, “What are you doing here? Have all your deer been eaten? Is your herd all gone? Why have you come?. And since he could talk, the deer king Shakyamuni Buddha said, | + | The [[king]] asked him, “What are you doing here? Have all your {{Wiki|deer}} been eaten? Is your herd all gone? Why have you come?. And since he could talk, the {{Wiki|deer}} [[king]] [[Shakyamuni Buddha]] said, “[[King]], you haven’t eaten all our {{Wiki|deer}}; on the contrary, we are prospering. Day by day our herds are increasing. You only eat one {{Wiki|deer}} a day, and in one day our does give [[birth]] to many fawns.” |

| − | The king said, “Then why have you come yourself?” | + | The [[king]] said, “Then why have you come yourself?” |

| − | Shakyamuni Buddha explained, “There is a pregnant doe whose fawn will be born in a day or so. It was her turn to come today, but since she wanted to wait until she had given birth to her fawn before she came to let the king eat her, she came to me and pleaded to have someone sent in her place. I thought over her request and realized that none of the deer in the herd would want to die before they had to, so I came myself to substitute for her.” | + | [[Shakyamuni Buddha]] explained, “There is a {{Wiki|pregnant}} doe whose fawn will be born in a day or so. It was her turn to come today, but since she wanted to wait until she had given [[birth]] to her fawn before she came to let the [[king]] eat her, she came to me and pleaded to have someone sent in her place. I [[thought]] over her request and [[realized]] that none of the {{Wiki|deer}} in the herd would want to [[die]] before they had to, so I came myself to substitute for her.” |

| − | When the king heard that, he was profoundly moved, and he said, “From now on, don’t send any more deer to the palace.” Then he spoke a verse: | + | When the [[king]] heard that, he was profoundly moved, and he said, “From now on, don’t send any more {{Wiki|deer}} to the palace.” Then he spoke a verse: |

| − | You are a deer with a human head. | + | You are a {{Wiki|deer}} with a [[human]] head. |

| − | I am a person with a deer’s head. | + | I am a [[person]] with a deer’s head. |

From this day forward, | From this day forward, | ||

| − | I will not eat the flesh of living beings. | + | I will not eat the flesh of [[living beings]]. |

| − | He said, “Although you have the head of a deer, you are a human being and although I have the head of a human being, I am a deer.” And then he vowed never to eat the flesh of living beings again. Because of that, the deer population in the park increased significantly; and the park was called the Deer Wilds Park. It was also named the Park of the Immortals because the | + | He said, “Although you have the head of a {{Wiki|deer}}, you are a [[human being]] and although I have the head of a [[human being]], I am a {{Wiki|deer}}.” And then he [[vowed]] never to eat the flesh of [[living beings]] again. Because of that, the {{Wiki|deer}} population in the park increased significantly; and the park was called the {{Wiki|Deer}} Wilds Park. It was also named the Park of the [[Immortals]] because the “[[wind]] and [[water]],” the [[geomantic]] lay of the land and its location, were particularly fine, and many [[immortals]] came there to cultivate the Way. So when [[Shakyamuni Buddha]] became a [[Buddha]], he went first to the {{Wiki|Deer}} Wilds Park to convert the five [[bhikshus]]. |

| − | And for the sake of Ajnatakaundinya and all five of the bhikshus. Three of the five bhikshus were relatives of the Buddha’s father and two were relatives of the Buddha’s mother. When the Buddha first left the palace to leave the home-life and cultivate the Way in the Himalayas, his parents had sent these relatives along after him to try to convince him to return. At that time the five bhikshus were not bhikshus, but high officials, and although they exhorted the Buddha to return, he would not. The five of them couldn’t go back and face the king, the Buddha’s father, without having accomplished their mission, so they stayed with the Buddha instead and accompanied him in cultivating the Way. | + | And for the sake of [[Ajnatakaundinya]] and all five of the [[bhikshus]]. Three of the five [[bhikshus]] were relatives of the [[Buddha’s]] father and two were relatives of the [[Buddha’s]] mother. When the [[Buddha]] first left the palace to leave the home-life and cultivate the Way in the [[Himalayas]], his [[parents]] had sent these relatives along after him to try to convince him to return. At that [[time]] the five [[bhikshus]] were not [[bhikshus]], but high officials, and although they exhorted the [[Buddha]] to return, he would not. The five of them couldn’t go back and face the [[king]], the [[Buddha’s]] father, without having accomplished their [[mission]], so they stayed with the [[Buddha]] instead and accompanied him in cultivating the Way. |

| − | Of the three who were his father’s relatives, one was called Ashvajit - the name means | + | Of the three who were his father’s relatives, one was called [[Ashvajit]] - the [[name]] means “[[horse]] victory”; one was called [[Bhadrika]] - the [[name]] means “little [[worthy]]”; and the other was called [[Mahanama]] [[Kulika]]. The two on the mother’s side were [[Ajnatakaundinya]] and [[Dashabala Kashyapa]], “drinker of light”, so named because he was a [[fire]] worshipper. The five stayed with the [[Buddha]] and cultivated [[ascetic]] practices, but eventually it became so [[bitter]] that three of them couldn’t take it and left. They backed out. The other two continued to cultivate with the [[Buddha]]. At that [[time]] the [[Buddha]] was eating only one grain of {{Wiki|rice}} and one sesame seed a day, and he became so emaciated that he was nothing but {{Wiki|skin}} and bones. Then one day a [[goddess]] brought him some milk gruel as an [[offering]]. He drank the gruel, and his [[body]] began to fill out again. The two who were cultivating with him got upset when they saw this, and they said, “How can someone who cultivates the Way drink milk gruel?” and so they left too. There was [[Shakyamuni Buddha]] in the midst of [[bitter]] cultivation and the five [[people]] his father and mother had sent to be with him all left him, three because they couldn’t take the [[suffering]], and two because they saw the [[Buddha]] enjoying his [[blessings]]. The [[Buddha]] remained alone to cultivate. After he had cultivated there for six years, he went to sit under the [[Bodhi tree]], and on the eighth day of the twelfth month he saw a star appear and became [[enlightened]]. “At night he saw a bright star and [[awakened]] to the Way.” After his [[enlightenment]], he looked into the {{Wiki|matter}} of who he should convert first, and saw that it was [[Ajnatakaundinya]], one of the five [[bhikshus]], who in a {{Wiki|past}} [[life]] had been the [[king]] of [[Kalinga]] and had cut the [[Buddha’s]] [[body]] limb from limb. In that [[life]] the [[Buddha]] had [[vowed]] that when he became a [[Buddha]] the first one he would save would be the [[king]] of [[Kalinga]]. That is why when [[Shakyamuni Buddha]] became [[enlightened]] he went first to the [[Deer Park]] and converted the five [[bhikshus]]. |

| − | Shakyamuni Buddha said, “For the sake of the five bhikshus as well as for you of the four-fold assembly” - the four-fold assembly consists of the bhikshus (monks), bhikshunis (nuns), upasakas (laymen), and upasikas (laywomen). “I said, ‘It is because living beings are impeded by guest-dust and affliction that they do not realize Bodhi or become Arhats.’” Why don’t living beings accomplish Buddhahood or become enlightened? Why don’t they accomplish the first fruit of arhatship? | + | [[Shakyamuni Buddha]] said, “For the sake of the five [[bhikshus]] as well as for you of the four-fold assembly” - the four-fold assembly consists of the [[bhikshus]] ([[monks]]), [[bhikshunis]] ([[nuns]]), [[upasakas]] ([[laymen]]), and [[upasikas]] ([[laywomen]]). “I said, ‘It is because [[living beings]] are impeded by guest-dust and [[affliction]] that they do not realize [[Bodhi]] or become [[Arhats]].’” Why don’t [[living beings]] accomplish [[Buddhahood]] or become [[enlightened]]? Why don’t they accomplish the first fruit of [[arhatship]]? |

| − | The phrase “guest-dust” also refers to your false thoughts. False thoughts are “guest-dust” and affliction. You can also say that “guest-dust” refers to the two kinds of delusion: view-delusion and thought-delusion. | + | The [[phrase]] “guest-dust” also refers to your false [[thoughts]]. False [[thoughts]] are “guest-dust” and [[affliction]]. You can also say that “guest-dust” refers to the two kinds of [[delusion]]: view-delusion and thought-delusion. “[[Afflictions]]” can also be said to be [[delusions]] of [[ignorance]] and [[delusions]] as numerous as motes of dust and sand. |

| − | Why are people impeded by “guest-dust” and affliction? Because people are really strange. They like to eat afflictions all day long. Fix them good food, give them some good bread and butter, and they won’t eat it. All they want to eat is afflictions, which they find more delicious than vegetable dumplings. Even if someone tells them not to eat affliction, they find it impossible to refrain from it. From morning to night, they eat nothing but “guest-dust” and afflictions and fill their bellies full of anger instead of food. People like that are truly pathetic. Shakyamuni Buddha said, “The reason all you living beings do not become Buddhas or Arhats is because you are impeded by ‘guest-dust’ and affliction.” | + | Why are [[people]] impeded by “guest-dust” and [[affliction]]? Because [[people]] are really strange. They like to eat [[afflictions]] all day long. Fix them good [[food]], give them some good bread and butter, and they won’t eat it. All they want to eat is [[afflictions]], which they find more delicious than vegetable dumplings. Even if someone tells them not to eat [[affliction]], they find it impossible to refrain from it. From morning to night, they eat nothing but “guest-dust” and [[afflictions]] and fill their bellies full of [[anger]] instead of [[food]]. [[People]] like that are truly pathetic. [[Shakyamuni Buddha]] said, “The [[reason]] all you [[living beings]] do not become [[Buddhas]] or [[Arhats]] is because you are impeded by ‘guest-dust’ and [[affliction]].” |

| − | At that time, what caused you who have now realized the holy fruit to become enlightened? “That | + | At that [[time]], what [[caused]] you who have now [[realized]] the {{Wiki|holy}} fruit to become [[enlightened]]? “That [[time]]” refers to the [[time]] when [[Shakyamuni Buddha]] went to the [[Deer Park]] and spoke [[dharma]]. “You” the [[Buddha]] means the five [[bhikshus]] and the fourfold assembly of [[bhikshus]], [[bhikshunis]], [[upasakas]], and [[upasikas]]. The [[Buddha]] asks them how and why they became [[enlightened]] when he talked about “guest-dust” and [[affliction]]. What meaning did they see that [[caused]] them to obtain the [[fruition]] of [[arhatship]]? |

| − | P2 Purna answers that the Buddha sealed and certified him. | + | P2 [[Purna]] answers that the [[Buddha]] sealed and certified him. |

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | Then Ajnatakaundinya arose and said to the Buddha, “Of the elders now present in the great assembly, only I received the name | + | Then [[Ajnatakaundinya]] arose and said to the [[Buddha]], “Of the [[elders]] now {{Wiki|present}} in the [[great assembly]], only I received the [[name]] ‘[[understanding]]’ because I was [[enlightened]] to the meaning of the [[word]] ‘guest-dust’ and [[realized]] the [[fruition]]. |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | Ajnatakaundinya was one of the five bhikshus. His name is interpreted to mean | + | [[Ajnatakaundinya]] was one of the five [[bhikshus]]. His [[name]] is interpreted to mean “[[understanding]] the fundamental limit” and also “the very first to understand” because he was the first to understand and to be certified as having attained [[arhatship]]. Then [[Ajnatakaundinya]] arose and said to the [[Buddha]]. [[Ajnatakaundinya]] stood up and spoke to the [[Buddha]]. Of the [[elders]] now {{Wiki|present}} in the [[great assembly]], only I received the [[name]] ‘[[understanding]]’ because I was [[enlightened]] to the meaning of the [[word]] ‘guest-dust’ and [[realized]] the [[fruition]]. He said, “Now in this [[great assembly]], I am an elder, I am older and much more [[experienced]]. Why did I receive the [[name]] ‘[[understanding]]’? Upon hearing the [[Buddha]] speak the [[word]] ‘guest-dust’ I understood the meaning and attained [[enlightenment]].” [[Ajnatakaundinya]] will explain the meaning of “guest-dust” in the following passages. |

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | "World Honored One, it is like a traveler who stops as a guest at a roadside inn, perhaps for the night or perhaps for a meal. When he has finished lodging there or when the meal is finished, he packs his baggage and sets out again. He does not remain there at leisure. The host himself, however, does not go far away. | + | "[[World Honored One]], it is like a traveler who stops as a guest at a roadside inn, perhaps for the night or perhaps for a meal. When he has finished lodging there or when the meal is finished, he packs his baggage and sets out again. He does not remain there at leisure. The host himself, however, does not go far away. |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | World Honored One. Ajnatakaundinya said, | + | [[World Honored One]]. [[Ajnatakaundinya]] said, “[[Buddha]], why was it that the two words ‘guest-dust’ brought about my [[enlightenment]]? It is like a traveler who stops as a guest at a roadside inn, perhaps for the night or perhaps for a meal. A guest who is on a journey, on a holiday, looks for an inn where he can stay for a while. Perhaps he stays overnight there, or perhaps he goes there to eat. When he has finished lodging there or when the meal is finished, he packs his baggage and sets out again. When he has finished eating and [[sleeping]], he readies his suitcases and goes on. He does not remain there at leisure. He’s a guest; he can’t live there all the [[time]]. The host himself, however, does not go far away.” The “host” refers to the [[pure]] [[nature]] and bright [[substance]] of the permanently dwelling true [[mind]]. The “guest” refers to false [[thinking]], the wearisome dust. |

| − | Why is it compared to “guest dust”? Because it is not something fundamental to us. Our bodies are basically clean, but if we go out on a windy day the dust may blow up and cover us, soiling our bodies. When we take our hands and brush away the dust, it disappears. What does this represent? It represents our afflictions and ignorance which are like “guest-dust”; they do not really exist. The guest is affliction and ignorance, the obstruction of affliction, the obstruction of what is known, the delusion of views and the delusion of thought. So Ajnatakaundinya understood that the guest at an inn stays only temporarily, whereas the host of the inn always lives there. | + | Why is it compared to “guest dust”? Because it is not something fundamental to us. Our [[bodies]] are basically clean, but if we go out on a windy day the dust may blow up and cover us, soiling our [[bodies]]. When we take our hands and brush away the dust, it disappears. What does this represent? It represents our [[afflictions]] and [[ignorance]] which are like “guest-dust”; they do not really [[exist]]. The guest is [[affliction]] and [[ignorance]], the obstruction of [[affliction]], the obstruction of what is known, the [[delusion]] of [[views]] and the [[delusion]] of [[thought]]. So [[Ajnatakaundinya]] understood that the guest at an inn stays only temporarily, whereas the host of the inn always [[lives]] there. |

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | "Considering it this way, the one who does not remain is called the guest, and the one who does remain is called the host. The word ‘guest’, then, means ‘one who does not remain.’ | + | "Considering it this way, the one who does not remain is called the guest, and the one who does remain is called the host. The [[word]] ‘guest’, then, means ‘one who does not remain.’ |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | Ajnatakaundinya concludes: Considering it this way, the one who does not remain is called the guest, and the one who does remain is called the host. We can also say that we reside in our bodies temporarily as a guest does in an inn. We should understand that our bodies are merely an inn, not an actual home. They are not our own home, and so we shouldn’t be too attached to them. But our host, the permanently dwelling true mind, never goes away, never ceases to exist. The word “guest,” then, means “one who does not remain.” | + | [[Ajnatakaundinya]] concludes: Considering it this way, the one who does not remain is called the guest, and the one who does remain is called the host. We can also say that we reside in our [[bodies]] temporarily as a guest does in an inn. We should understand that our [[bodies]] are merely an inn, not an actual home. They are not our own home, and so we shouldn’t be too [[attached]] to them. But our host, the permanently dwelling true [[mind]], never goes away, never ceases to [[exist]]. The [[word]] “guest,” then, means “one who does not remain.” |

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | "Again, when the sky clears up, the morning sun rises with all resplendence, and its golden rays stream into a house through a crevice to reveal particles of dust in the air. The dust dances in the rays of light, but the empty space is motionless. | + | "Again, when the sky clears up, the morning {{Wiki|sun}} rises with all resplendence, and its golden rays {{Wiki|stream}} into a house through a crevice to reveal {{Wiki|particles}} of dust in the [[air]]. The dust dances in the [[rays of light]], but the [[empty]] [[space]] is motionless. |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | Again, when the sky clears up, the morning sun rises with all resplendence, and its golden rays stream into a house through a crevice to reveal particles of dust in the air. When the sun has just come up, early on a clear fresh morning, a morning after a rain, the sun shines through a crack in the door or perhaps a crack in the wall, and it displays the fine bits of dust bobbing up and down in empty space, moving all around in the sunshine. The dust dances in the rays of light, but the empty space is motionless. If the sun doesn’t shine in the crack, you can’t see the dust, although there is actually a lot of dust everywhere. But while the dust moves and bobs up and down, empty space is still. It doesn’t move. The ability to see the dust in the light that pours through the crack represents the attainment of the light of wisdom. When you certify to the fruit and reach the first stage of arhatship and overcome the 88 categories of view-delusion, you have the light of wisdom. Then you can see your ignorance, which causes afflictions as numerous as motes of dust or grains of sand in the Ganges River. The sun of wisdom shines on the dust-particles of affliction, as in Ajnatakaundinya’s analogy of the sun shining through the crack. The dark caverns of ignorance are illumined, and you see the dust of affliction, and you understand. | + | Again, when the sky clears up, the morning {{Wiki|sun}} rises with all resplendence, and its golden rays {{Wiki|stream}} into a house through a crevice to reveal {{Wiki|particles}} of dust in the [[air]]. When the {{Wiki|sun}} has just come up, early on a clear fresh morning, a morning after a [[rain]], the {{Wiki|sun}} shines through a crack in the door or perhaps a crack in the wall, and it displays the fine bits of dust bobbing up and down in [[empty]] [[space]], moving all around in the sunshine. The dust dances in the [[rays of light]], but the [[empty]] [[space]] is motionless. If the {{Wiki|sun}} doesn’t shine in the crack, you can’t see the dust, although there is actually a lot of dust everywhere. But while the dust moves and bobs up and down, [[empty]] [[space]] is still. It doesn’t move. The ability to see the dust in the light that pours through the crack represents the [[attainment]] of [[the light of wisdom]]. When you certify to the fruit and reach the first stage of [[arhatship]] and overcome the 88 categories of view-delusion, you have [[the light of wisdom]]. Then you can see your [[ignorance]], which [[causes]] [[afflictions]] as numerous as motes of dust or grains of sand in the [[Ganges River]]. The {{Wiki|sun}} of [[wisdom]] shines on the dust-particles of [[affliction]], as in Ajnatakaundinya’s analogy of the {{Wiki|sun}} shining through the crack. The dark caverns of [[ignorance]] are illumined, and you see the dust of [[affliction]], and you understand. |

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | "Considering it this way, what is clear and still is called space, and what moves is called dust. The word ‘dust’, then, means 'that which moves.’ ” | + | "Considering it this way, what is clear and still is called [[space]], and what moves is called dust. The [[word]] ‘dust’, then, means 'that which moves.’ ” |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | Ignorance and afflictions as numerous as motes of dust move, but empty space does not move. Empty space represents our seeing-nature, which is also unmoving. It is the genuine host, our permanently dwelling true mind which does not come and does not go. | + | [[Ignorance]] and [[afflictions]] as numerous as motes of dust move, but [[empty]] [[space]] does not move. [[Empty]] [[space]] represents our seeing-nature, which is also unmoving. It is the genuine host, our permanently dwelling true [[mind]] which does not come and does not go. |

| − | Considering it this way, what is clear and still is called space. Clear and still, it does not move, and that is called space. And what moves is called dust. The word “dust”, then, means “that which moves.” You see the bits of dust in the patch of sunshine dancing and flying about ceaselessly. What is this dust? It represents affliction, ignorance, the obstacle of affliction, and the obstacle of what is known. Attachment to those things is called “dust”. | + | Considering it this way, what is clear and still is called [[space]]. Clear and still, it does not move, and that is called [[space]]. And what moves is called dust. The [[word]] “dust”, then, means “that which moves.” You see the bits of dust in the patch of sunshine [[dancing]] and flying about ceaselessly. What is this dust? It represents [[affliction]], [[ignorance]], the [[obstacle]] of [[affliction]], and the [[obstacle]] of what is known. [[Attachment]] to those things is called “dust”. |

| − | Every day you listen to the sutra and I tell you not to have afflictions, and all you’ve got is afflictions. I tell you not to have ignorance and all you do is display your ignorance. Would you call this being obedient? The more it is said that ignorance is not a good thing, the greater the ignorance becomes. When it is said that afflictions aren’t good, the afflictions grow. Before it was discussed, there were no afflictions, but once it was brought up, the afflictions came forth. So it must be that my explanation of the sutra isn’t a good explanation, because I haven’t been able to explain away your afflictions. I hope you will all toss your afflictions into the Pacific Ocean. Don’t look upon your afflictions as precious treasures. Don’t treat afflictions as if they were your own kin. Don’t let affliction be your playmate with birth and death. Don’t be so affectionate towards them. You should toss your afflictions into the ocean, even though there are so many of them that they might well fill up the entire ocean. | + | Every day you listen to the [[sutra]] and I tell you not to have [[afflictions]], and all you’ve got is [[afflictions]]. I tell you not to have [[ignorance]] and all you do is display your [[ignorance]]. Would you call this being obedient? The more it is said that [[ignorance]] is not a good thing, the greater the [[ignorance]] becomes. When it is said that [[afflictions]] aren’t good, the [[afflictions]] grow. Before it was discussed, there were no [[afflictions]], but once it was brought up, the [[afflictions]] came forth. So it must be that my explanation of the [[sutra]] isn’t a good explanation, because I haven’t been able to explain away your [[afflictions]]. I {{Wiki|hope}} you will all toss your [[afflictions]] into the {{Wiki|Pacific Ocean}}. Don’t look upon your [[afflictions]] as [[precious]] [[treasures]]. Don’t treat [[afflictions]] as if they were your own kin. Don’t let [[affliction]] be your playmate with [[birth]] and [[death]]. Don’t be so affectionate towards them. You should toss your [[afflictions]] into the ocean, even though there are so many of them that they might well fill up the entire ocean. |

| − | Afflictions are demons. Where do you find demons and demonic ghosts? To have demonic ghosts is simply to have afflictions. You and the demons have gotten together. Afflictions are absolutely terrible, and the sutra is being explained just to teach people to get rid of their afflictions, so don’t let it be that the more we speak of afflictions the more they multiply. | + | [[Afflictions]] are {{Wiki|demons}}. Where do you find {{Wiki|demons}} and {{Wiki|demonic}} [[ghosts]]? To have {{Wiki|demonic}} [[ghosts]] is simply to have [[afflictions]]. You and the {{Wiki|demons}} have gotten together. [[Afflictions]] are absolutely terrible, and the [[sutra]] is being explained just to teach [[people]] to get rid of their [[afflictions]], so don’t let it be that the more we speak of [[afflictions]] the more they multiply. |

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | The Buddha said, “So it is.” | + | The [[Buddha]] said, “So it is.” |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | After Ajnatakaundinya finished speaking, the Buddha gave him positive certification. He said, “What you have said is correct.” The Buddha said, “So it is.” What moves is dust, what does not move is space. Your theory is not mistaken. | + | After [[Ajnatakaundinya]] finished {{Wiki|speaking}}, the [[Buddha]] gave him positive certification. He said, “What you have said is correct.” The [[Buddha]] said, “So it is.” What moves is dust, what does not move is [[space]]. Your {{Wiki|theory}} is not mistaken. |

</poem> | </poem> | ||

| − | ===Seeing Does Not Become Extinct=== | + | ===[[Seeing]] Does Not Become [[Extinct]]=== |

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | N3 He shows that the seeing does not become extinct. | + | N3 He shows that the [[seeing]] does not become [[extinct]]. |

O1 The assembly considers this and asks for further instruction. | O1 The assembly considers this and asks for further instruction. | ||

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | When Ananda and the great assembly heard the Buddha’s instructions, they became peaceful and composed both in body and mind. They recollected that since time without beginning, they had strayed from their fundamental true mind by mistaking the shadows of their causally conditioned differentiating minds as something real and substantial. Now on this day they had awakened to such illusions and misconceptions. Like a lost infant who rejoins its beloved mother after a long separation, they put their palms together to make obeisance to the Buddha. | + | When [[Ananda]] and the [[great assembly]] heard the [[Buddha’s]] instructions, they became [[peaceful]] and composed both in [[body]] and [[mind]]. They recollected that since [[time]] without beginning, they had strayed from their fundamental true [[mind]] by mistaking the shadows of their [[causally]] [[conditioned]] differentiating [[minds]] as something real and substantial. Now on this day they had [[awakened]] to such [[illusions]] and misconceptions. Like a lost {{Wiki|infant}} who rejoins its beloved mother after a long separation, they put their palms together to make obeisance to the [[Buddha]]. |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | When Ananda and the great assembly heard the Buddha’s instructions. When Ananda and the great Bodhisattvas, the great Arhats, and the great bhikshus, and the others heard this teaching, they became peaceful and composed both in body and mind. Their bodies and minds felt extremely comfortable, so that they didn’t feel the least bit of pain. They had never felt better. They had never known anything so fine. But at the same time, they recollected that since time without beginning, they had strayed from their fundamental true mind by mistaking the shadows of their causally conditioned differentiating minds as something real and substantial. From time without beginning they had renounced their basic mind and had used only their false mind, their conscious mind, their mind which makes distinctions in order to do things. They hadn’t understood external states; they’d taken their false-thinking mind to be true and actual. They had engaged in false activities at the gates of the six organs and hadn’t the least bit of skill when it came to the self-nature. In order to function, they dealt exclusively with the false-thinking mind, the attached mind, the arrogant mind, the mind which seizes upon conditions, the mind which is false in various kinds of ways. Now on this day they had awakened to such illusions and misconceptions. Like a lost infant who rejoins its beloved mother after a long separation, they put their palms together to make obeisance to the Buddha. They had been like a hungry child who had no milk to drink; it had been very painful. All of a sudden the child’s compassionate mother had returned, and the child had milk to drink: that is what it was like for the assembly when they awakened upon hearing the Buddha’s instruction. They placed their palms together and bowed to the Buddha to thank him for his kindness in bestowing the dharma upon them. | + | When [[Ananda]] and the [[great assembly]] heard the [[Buddha’s]] instructions. When [[Ananda]] and the great [[Bodhisattvas]], the great [[Arhats]], and the great [[bhikshus]], and the others heard this [[teaching]], they became [[peaceful]] and composed both in [[body]] and [[mind]]. Their [[bodies]] and [[minds]] felt extremely comfortable, so that they didn’t [[feel]] the least bit of [[pain]]. They had never felt better. They had never known anything so fine. But at the same [[time]], they recollected that since [[time]] without beginning, they had strayed from their fundamental true [[mind]] by mistaking the shadows of their [[causally]] [[conditioned]] differentiating [[minds]] as something real and substantial. From [[time]] without beginning they had renounced their basic [[mind]] and had used only their false [[mind]], their [[conscious mind]], their [[mind]] which makes distinctions in order to do things. They hadn’t understood external states; they’d taken their false-thinking [[mind]] to be true and actual. They had engaged in false [[activities]] at the gates of the six {{Wiki|organs}} and hadn’t the least bit of skill when it came to the [[self-nature]]. In order to [[function]], they dealt exclusively with the false-thinking [[mind]], the [[attached]] [[mind]], the [[arrogant]] [[mind]], the [[mind]] which seizes upon [[conditions]], the [[mind]] which is false in various kinds of ways. Now on this day they had [[awakened]] to such [[illusions]] and misconceptions. Like a lost {{Wiki|infant}} who rejoins its beloved mother after a long separation, they put their palms together to make obeisance to the [[Buddha]]. They had been like a hungry child who had no milk to drink; it had been very [[painful]]. All of a sudden the child’s [[compassionate]] mother had returned, and the child had milk to drink: that is what it was like for the assembly when they [[awakened]] upon hearing the [[Buddha’s]] instruction. They placed their palms together and [[bowed]] to the [[Buddha]] to thank him for his [[kindness]] in bestowing the [[dharma]] upon them. |

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | They wished to hear such words from the Thus Come One as to enlighten them to the dual nature of body and mind - what is false and what is real, what is empty and what is substantial, what is subject to production and extinction and what transcends production and extinction. | + | They wished to hear such words from the [[Thus Come One]] as to [[enlighten]] them to the dual [[nature]] of [[body]] and [[mind]] - what is false and what is real, what is [[empty]] and what is substantial, what is [[subject]] to production and [[extinction]] and what transcends production and [[extinction]]. |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | Why did the assembly bow to the Buddha? Because they wished to hear such words from the Thus Come One as to enlighten them to the dual nature of body and mind. They wanted him to uncover it and portray it clearly, to reveal what is false and what is real, what is empty and what is substantial. There is the true and the false, the empty and the actual, and they wanted the Buddha to teach them to recognize each of them. They wanted him to reveal what is subject to production and extinction and what transcends production and extinction - to reveal the mind’s dual nature, the mind with superficial production and extinction and the mind that is not subject to production and extinction. | + | Why did the assembly [[bow]] to the [[Buddha]]? Because they wished to hear such words from the [[Thus Come One]] as to [[enlighten]] them to the dual [[nature]] of [[body]] and [[mind]]. They wanted him to uncover it and portray it clearly, to reveal what is false and what is real, what is [[empty]] and what is substantial. There is the true and the false, the [[empty]] and the actual, and they wanted the [[Buddha]] to teach them to [[recognize]] each of them. They wanted him to reveal what is [[subject]] to production and [[extinction]] and what transcends production and [[extinction]] - to reveal the [[mind’s]] dual [[nature]], the [[mind]] with [[superficial]] production and [[extinction]] and the [[mind]] that is not [[subject]] to production and [[extinction]]. |

| − | What is the mind of production and extinction? It is the conscious mind, our mind which seizes upon conditions by turning to the outside and seeking there, instead of developing skill at the self-nature. What is the mind not subject to production and extinction? You must apply your skill to the self-nature and understand that the mountains, the rivers, the great earth, the vegetation, and all the myriad appearances are all the dharma body of all Buddhas. The dharma body of all Buddhas is neither produced nor extinguished. And the pure nature and bright substance of everyone’s permanently dwelling true mind is also not produced and not extinguished. | + | What is the [[mind]] of production and [[extinction]]? It is the [[conscious mind]], our [[mind]] which seizes upon [[conditions]] by turning to the outside and seeking there, instead of developing skill at the [[self-nature]]. What is the [[mind]] not [[subject]] to production and [[extinction]]? You must apply your skill to the [[self-nature]] and understand that the [[mountains]], the [[rivers]], the great [[earth]], the vegetation, and all the myriad [[appearances]] are all the [[dharma body]] of all [[Buddhas]]. The [[dharma body]] of all [[Buddhas]] is neither produced nor [[extinguished]]. And the [[pure]] [[nature]] and bright [[substance]] of everyone’s permanently dwelling true [[mind]] is also not produced and not [[extinguished]]. |

| − | Why do we have production and extinction, birth and death? | + | Why do we have production and [[extinction]], [[birth]] and [[death]]? |

| − | It is because we do not recognize the pure nature and bright substance of the permanently dwelling true mind. It is also because your mad mind has not ceased. So it is said, “when the mad mind ceases, that ceasing is Bodhi.” The mad mind’s stopping itself is the manifestation of your Bodhi mind. Because the mad mind exists and has not ceased, the Bodhi mind cannot come forth. The mad mind covers it over. What is being explained now, and in every other passage of sutra text without exception, has the aim of revealing everyone’s true mind. | + | It is because we do not [[recognize]] the [[pure]] [[nature]] and bright [[substance]] of the permanently dwelling true [[mind]]. It is also because your mad [[mind]] has not ceased. So it is said, “when the mad [[mind]] ceases, that ceasing is [[Bodhi]].” The mad [[mind’s]] stopping itself is the [[manifestation]] of your [[Bodhi mind]]. Because the mad [[mind]] [[exists]] and has not ceased, the [[Bodhi mind]] cannot come forth. The mad [[mind]] covers it over. What is being explained now, and in every other passage of [[sutra]] text without exception, has the aim of revealing everyone’s true [[mind]]. |

| − | O2 King Prasenajit tells his situation and makes a special request. | + | O2 [[King]] [[Prasenajit]] tells his situation and makes a special request. |

| − | '''Sutra: | + | '''[[Sutra]]: |

| − | Then King Prasenajit rose and said to the Buddha, “In the past, when I had not yet received the teachings of the Buddha, I met Katyayana and Vairatiputra, both of whom said that this body is annihilated after death, and that this is nirvana. Now, although I have met the Buddha, I still have doubts about their words. How much I wish to be enlightened to the ways and means to perceive and realize the true mind, thereby proving that it transcends production and extinction! All those who have outflows also wish to be instructed on this subject.” | + | Then [[King]] [[Prasenajit]] rose and said to the [[Buddha]], “In the {{Wiki|past}}, when I had not yet received the teachings of the [[Buddha]], I met [[Katyayana]] and Vairatiputra, both of whom said that this [[body]] is annihilated after [[death]], and that this is [[nirvana]]. Now, although I have met the [[Buddha]], I still have [[doubts]] about their words. How much I wish to be [[enlightened]] to the ways and means to {{Wiki|perceive}} and realize the true [[mind]], thereby proving that it transcends production and [[extinction]]! All those who have outflows also wish to be instructed on this [[subject]].” |

'''Commentary: | '''Commentary: | ||

| − | Then - before the Buddha spoke - King Prasenajit rose in the great assembly. King Prasenajit’s name means | + | Then - before the [[Buddha]] spoke - [[King]] [[Prasenajit]] rose in the [[great assembly]]. [[King]] Prasenajit’s [[name]] means “[[moonlight]]” in [[Sanskrit]], as mentioned before. The [[king]] was born at the same [[time]] that the [[Buddha]] entered the [[world]]. Upon entering the [[world]] the [[Buddha]] emitted light, but [[King]] Prasenajit’s father [[thought]] that it was his son who was emitting the light as he came into the [[world]], so he named him “[[Moonlight]].” |