Difference between revisions of "Buddhism and Spinoza by Joseph B. Yesselman"

(Created page with "thumb|250px| <poem> 1. Unless otherwise noted all material herein is taken from The Teaching Company's "Buddhism"; 12 cassettes, 2 course guide bo...") |

m (Text replacement - "]]]" to "]])") |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Spinoza.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Spinoza.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | < | + | '''Notes'''<br/> |

| − | 1. Unless otherwise noted all material herein is taken from The Teaching Company's | + | 1. Unless otherwise noted all material herein is taken from The [[Teaching]] Company's "[[Buddhism]] "; 12 cassettes, 2 course guide [[books]] (CG1, CG2), and 2 transcript [[books]] (TB1 & TB2); all authored by Prof. [[Malcolm David Eckel]]. © 2001 The [[Teaching]] Company Limited Partnership |

| − | + | Only parts of seven Lectures (Lectures 1 to 6, & 12.) of a total of 24 Lectures are included herein. I unrestrainedly recommend your study of The [[Teaching]] Company's "[[Buddhism]] " for the complete 24 Lectures | |

| − | 2. Symbols: | + | 2. [[Symbols]]: |

| − | + | Unless noted, all comments are from The [[Teaching]] Company's "[[Buddhism]] " or Prof. [[Eckel]]. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | :{JBY opinion—or where, I think, Spinozism concurs or differs with [[Buddhism]] ; or, Spinozism's [[world]] view.} | |

| − | + | :R<comment from Robison and Johnson>R:Page Number | |

| + | :S<comment from Strong>S:Page Number | ||

[[File:PhatAdiDa9.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:PhatAdiDa9.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | 3. My purpose is to show the insights of Buddhism and also where Spinoza's insights would, | + | 3. My {{Wiki|purpose}} is to show the [[insights]] of [[Buddhism]] and also where [[Spinoza's]] [[insights]] would, |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | I believe, concur or differ. I use the [[word]] differ instead of disagree because disagree implies one or the other is wrong. Whereas differ implies they are both correct and useful for the '[[world]] view' held. These different '[[world]] [[views]]' are [[caused]] by differences of {{Wiki|culture}}, economic [[development]], technological [[development]], {{Wiki|environmental}} [[conditions]], climate, personal disposition, etc., etc., etc. On the whole, I believe {{Wiki|Spinoza}} puts into {{Wiki|modern}} [[rational]] [[language]] the [[insights]] of [[Buddhism]] and avoids unfamiliar [[parables]] and unfamilar catch-words such as '[[Emptiness]] ', 'No {[[permanent]]} [[self]] ", and '[[Nirvana]] '. See Spinozism for some concurrences and some differences. Again, over the centuries, like any other [[religion]] , [[Buddhism]] has changed and evolved as [[conditions]] change, L12:II. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Lecture One== | |

| − | + | ===What is [[Buddhism]] ?=== | |

| − | [[ | + | CG1:3 |

| − | |||

| − | + | '''Scope''': | |

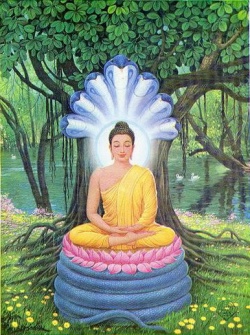

| − | + | In its 2,500-year history, from the [[time]] of the [[Buddha]] to the {{Wiki|present}} day, [[Buddhism]] has grown from a tiny [[religious]] {{Wiki|community}} in northern [[India]] into a {{Wiki|movement}} that now spans the {{Wiki|globe}}. It has shaped the [[development]] of {{Wiki|civilization}} in [[India]] and {{Wiki|Southeast Asia}}; has had major influence on the {{Wiki|civilizations}} of [[China]] , [[Tibet]] , [[Korea]] , and [[Japan]] ; and today has become a major part of the multi-[[religious]] [[world]] of {{Wiki|Europe}} and [[North America]]. Through all of its many changes, what is [[Buddhism]] , and how should we study it? These lectures will explore the [[Buddhist]] [[tradition]] as the unfolding of a story. It is the story of the [[Buddha]] himself and the story of generations of [[people]] who have used the model of the [[Buddha]] 's [[life]] to shape not only their [[own]] [[lives]] but the {{Wiki|societies}} in which they live. | |

| − | + | [[File:Tiantai0045.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | |

| − | + | '''Outline''': | |

| − | + | I. [[Buddhism]] originated in northern [[India]] around 500 B.C.E.. | |

| + | :A. The [[tradition]] gets its [[name]] from a man who was known by his followers as the [[Buddha]] , or the "[[Awakened]] {[[enlightened]] } One." | ||

| − | + | ::1. He was born into a princely [[family]] in a region of northern [[India]] that is now in southern [[Nepal]] . | |

| + | ::2. He often is depicted sitting very serenely, with his feet crossed in front of him and his hands folded in his lap. He is the very picture of [[calm]] and [[Wikipedia:contemplation|contemplation]] . This is the image that has drawn [[people]] to the [[Buddha]] for many centuries, and it is the one that conveys most explicitly the [[experience]] of his [[awakening]] . | ||

| + | ::3. But the [[Buddha]] did not always sit still in {{Wiki|perfect}} [[Wikipedia:contemplation|contemplation]] . After his [[awakening]] , he got up from his seat and [[taught]] his [[experience]] to others on the roads of northern [[India]] . {[[Spinoza's]] teachings—Ethics, TEI, TTP.} | ||

| + | ::4. The major events of the [[Buddha]] 's [[life]] took place in the [[Madhyadesha]], or the "Middle Region" of the [[Ganges]] Basin. (These sites are still the focus of [[Buddhist]] [[pilgrimage]] today.) | ||

[[File:145-io.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:145-io.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | + | ::5. To understand the significance of the [[Buddha]] 's [[life]] , we will spend two lectures, right at the beginning of our course, studying the [[religious]] background that made it possible for the [[Buddha]] to have such a strong [[religious]] impact on [[Indian]] {{Wiki|civilization}}. | |

| − | + | ::6. Then we will discuss the three categories, or '[[jewels]]," that are fundamental to [[Buddhist]] [[life]] . We will spend one lecture on the [[life]] of the [[Buddha]] himself; two lectures on his [[teaching]], or [[dharma]] ; one lecture on the [[development]] of the early [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|community}}; and one lecture on the [[tradition]] of [[Buddhist]] [[art]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | CG1:5<br/> | |

| + | II. | ||

| + | :D. When we study the [[teaching]] of the [[Buddha]] , we will see that the diversity of the [[Buddhist]] [[tradition]] is no surprise. | ||

| − | + | ::1. The [[Buddha]] said that everything is [[impermanent]] {perishable}. The [[evolution]] of the [[Buddhist]] [[tradition]] itself exemplifies [[truth]] . | |

| + | ::2. The [[Buddha]] also said that [[nothing]] has any [[permanent]] [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]]. (This is the famous [[Buddhist]] [[doctrine]] of "no {[[permanent]]} [[self]] " and {I-thee}.") Momentary [[phenomena]] give the [[illusion]] of continuity {but they are real} , like the moments of flowing [[water]] that make up the current of a [[river]] or the flickers of burning gas that make up the flame of a candle. | ||

[[File:Munk66814 n.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Munk66814 n.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | + | ::3. As the [[Buddhist]] [[tradition]] has changed and adapted to new situations and new needs, it sometimes has changed so radically that it is hard to know anymore what makes it "[[Buddhist]] ." | |

| − | CG1:6 | + | CG1:6<br/> |

| − | IV. Finally, I hope the story of the Buddha and the story of Buddhism will in some way become | + | IV. Finally, I {{Wiki|hope}} the story of the [[Buddha]] and the story of [[Buddhism]] will in some way become yours as well. |

| − | + | :A. [[Buddhism]] can be a great challenge to [[people]] who have grown up in the [[Western]] [[world]] and think that [[religion]] has to do with the {{Wiki|worship}} of a single, almighty [[God]] . | |

| + | ::1. The [[Buddha]] did not accept the [[existence]] of a single [[God]] {or any [[god]] (s)} who created the [[world]] . {Deus—Spinoza's G-D is simliar to the [[Buddha]] 's.} | ||

| + | ::2. For that [[matter]] , he did not accept the [[idea]] of a [[permanent]] [[self]] .<br/>Momentary [[phenomena]] give the [[illusion]] of continuity, like the moments of flowing [[water]] that make up the current of a [[river]] or the flickers of burning gas that make up the flame of a candle. | ||

| − | + | :B. Some [[people]] think that [[Buddhism]] is so different from all we know as [[religion]] in the [[Western]] [[world]] that it should be called a [[philosophy]] of [[life]] rather than a {[[scriptural]] {{Wiki|theology}}, [[Miracles]] , etc.} [[religion]]. | |

| + | [[File:Mucalinda Naga.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | + | :C. Either way, [[Buddhism]] challenges us to think in new ways about the [[nature]] of the [[world]] and the possibility of a satisfying and {{Wiki|productive}} [[human]] [[life]] . {Obtaining PcM.} | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Shirley's Book.VII:235—Deus | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :Although {{Wiki|Spinoza}} {and [[Buddhism]] and [[Krishna]]} gives repeated warnings that his "[[Deus]]" is far from the {{Wiki|anthropomorphic}} {{Wiki|conception}} of [[God]] prevalent in the {{Wiki|theology}} of his [[time]] , the reader will find it difficult to bear this constantly in [[mind]]. It is not until E1:XIV:54, that G-D, by [[definition]] {{{Wiki|hypothesis}}}, is shown to be [[identical]] with the [[infinite]], all-inclusive, unique [[substance]], and thereafter it is all too easy to lose [[sight]] of this, as the [[religious]] overtones of the [[word]] "[[God]] " keep asserting themselves. So [[Spinoza's]] frequent use of the [[phrase]] "[[Deus]] sive Natura"— G-D that is Nature—is intended as a salutary corrective. {The terms G-D and [[Nature]] are interchangeable.} For {{Wiki|Spinoza}} G-D is all Being, all [[Reality]] , in all its aspects and in all its [[infinite]] richness. {Isaac B. Singer} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Lecture Two | + | ==Lecture Two== |

| − | + | ===[[India]] at the [[Time]] of the [[Buddha]] === | |

| + | CG1:9 | ||

| − | Scope: | + | '''Scope''': |

[[File:Tiantai8 o.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Tiantai8 o.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The story of [[Buddhism]] begins in [[India]] in the sixth century B.C.E. with the [[birth]] of [[Siddhartha Gautama]] , the man who was known as the "[[Awakened]] {[[enlightened]] } One," or [[Buddha]] . What was the [[Buddha]] 's [[religious]] and {{Wiki|cultural}} background {Note 3}? What problems did he inherit? Why did he respond to them in the way he did? To answer these questions, we begin our study of [[Buddhism]] by looking back into the [[Vedas]] , the earliest surviving [[scriptures]] of the [[Hindu]] [[tradition]] . The [[Vedas]] tell us about the [[lives]] of [[Indian]] [[sages]] and about an [[Indian]] quest for [[wisdom]] about the [[nature]] of the [[world]] and the [[self]] . When [[Siddhartha Gautama]] "woke up" to the [[truth]] and became the [[Buddha]] , this {{Wiki|distinctive}} [[insight]] made him one of the most {{Wiki|eminent}} and influential of these [[Indian]] [[sages]]. | |

| − | + | CG1:23<br/> | |

| − | + | III. To unpack the [[religious]] history of [[India]] , we turn first to a [[body]] of texts known as the [[Vedas]] . | |

| − | + | :A. These are the most authoritative texts in the [[Hindu]] [[tradition]] and the oldest surviving [[religious]] texts in [[India]] . The earliest hymns in the [[Vedas]] can be dated about 1500-1000 B.C.E.. | |

| + | ::8. One of the last hymns in the {{Wiki|Vedic}} collection posed what I think of as the classic {{Wiki|Vedic}} question. Let me summarize it {[[intellectual]] [[love]] of G-D} so that you can get an [[impression]] of the content of these hymns and [[feel]] the force of the question: | ||

[[File:Mara3321.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Mara3321.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | + | :::There was not then either [[Wikipedia:Existence|nonexistence]] or [[existence]] (either asat or sat). There was no sky, and there were no [[heavens]]. What was it that covered everything? What was its [[protection]]? Was there a bottomless depth of waters? | |

| − | + | :::There was neither [[death]] nor [[immortality]] , neither day nor night. The One breathed, though uninspired by [[breath]], by its [[own]] potentiality. Beside it [[nothing]] existed... | |

| − | + | :::Who is there who [[knows]]? Who can tell its origin? Who can tell the source of this creation? The [[gods]] are on this side of the creation. Who [[knows]], then, where it came from and how it came into being? | |

| + | :::Where this creation came from and how it came into being—perhaps the [[highest]] overseer in [[heaven]] [[knows]], or perhaps even he does not know. | ||

| − | + | ::::—Rig [[Veda]] 10.129 <br/>(W. Norman Brown, Man in the [[Universe]] , pp. 29-30). | |

| − | + | :9. You can see that as these early {{Wiki|priests}} composed their hymns around the year 1200 B.C.E., they asked a question about the origin of the [[universe]] . The question took them, in a [[sense]] , beyond the [[gods]] . They wanted to know where everything came from, with {{Wiki|emphasis}} on the [[word]] know. You can also [[feel]] just a suggestion, perhaps, that if they knew {understood} the source of everything, they would know the connection between themselves {as modes} and the rest of the [[cosmos]], and they would be able to control it {and achieve [[peace]] of [[mind]]}. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | CG1:23 | + | CG1:23<br/> |

| − | III. To unpack the religious history of India, we turn first to a body of texts known as the Vedas. | + | III. To unpack the [[religious]] history of [[India]] , we turn first to a [[body]] of texts known as the [[Vedas]] . |

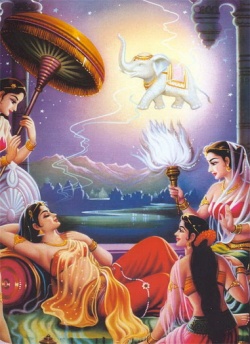

[[File:Maya dreams0023.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Maya dreams0023.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | + | :C. The [[Wikipedia:Upanishads|Upanishads]] tell stories of {{Wiki|priests}} who tried to find {{Wiki|unity}} in the fragmented [[world]] of {{Wiki|Vedic}} [[ritual]] . They focused their speculation in three areas. | |

| − | + | ::1. They identified the [[essence]] of external [[reality]] (or the [[macrocosm]] {the [[universe]] considered as a whole}) as "Being" or "[[Reality]] " (sat - being, is). | |

| − | + | ::2. They identified the [[essence]] of their [[own]] personalities (or the [[microcosm]] {a part of the [[universe]] —a mode}) as "[[Self]] " ([[atman]] ). | |

| − | + | ::3. They identified the [[essence]] of the sacrificial [[ritual]] (or the mesocosm) as [[brahman]] . The [[word]] [[brahman]] originally meant "[[prayer]] ." Here it refers to the [[power]] or [[reality]] that lies behind the [[prayer]] . | |

| − | + | ::4. Once these three {sat = [[atman]] = [[brahman]] } [[essential]] [[realities]] had been identified, the [[Upanishadic]] [[sages]] made a great imaginative leap {{{Wiki|hypothesis}}} and said that all three were aspects of the same thing {G-D}. This leap of the {{Wiki|Vedic}} [[imagination]] resulted in the [[doctrine]] of [[Upanishadic]] {{Wiki|monism}}, the view that all of [[reality]] is one. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :D. [[Upanishadic]] {{Wiki|monism}} can be expressed positively, as it is in the story of [[Shvetaketu]] and his father, Aruni. | |

| − | + | ::1. One day, Aruni told his son that it was [[time]] for him to take up the [[life]] of a [[student]], and he sent him away to study. When he came back at the age of twenty-four, [[feeling]] swell-headed and [[arrogant]] with all the things he had learned, his father asked him whether he had heard about the "[[principle]] of substitution"—"by which one hears what has not been heard of before and [[thinks]] what has not been [[thought]] of before." [[Shvetaketu]] says that he has not, and Aruni begins to teach him. | |

[[File:14es.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:14es.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | + | ::2. "It is like this," he said. "By means of one lump of clay {[[substance]]} one would {{Wiki|perceive}} everything made of clay—the [[transformation]] is a [[verbal]] handle , a [[name]] {a mode} —while the [[reality]] is just this: 'Its clay.'" | |

| + | ::3. Then he applies this [[principle]] in a series of [[discourses]] {examples} that [[sound]] to us like [[philosophical]] [[poetry]] : | ||

| − | + | :::The bees, my dear son, prepare [[honey]] by [[gathering]] the [[nectar]] of different [[trees]] and reducing that [[nectar]] to a {{Wiki|unity}}. So, that the [[nectar]] from each different [[tree]] is not able to differentiate: "I am the [[nectar]] of this [[tree]] " and "I am the [[nectar]] of that [[tree]] ." In exactly the same way, my son, when all creatures merge into [[reality]] , they are not {{Wiki|aware}} that "We are merging into [[reality]] ." No {{Wiki|matter}} what they are in this [[world]] —whether they are a [[tiger]]. a [[lion]] , a {{Wiki|wolf}}, a {{Wiki|boar}}, a worm, a moth, a gnat, or a mosquito—they all merge into that [[reality]] . That finest [[essence]] here is the [[self]] of the whole [[world]] . That is [[reality]] ; that is the [[self]]. And that [[art]] thou, [[Shvetaketu]]. {[[Spinoza's]] [[Pantheism]].} | |

| + | ::::—[[Chandogya Upanishad]]<br/>(Robert Ernest [[Hume]], trans., The Thirteen [[Principal]] [[Wikipedia:Upanishads|Upanishads]], 2nd ed. [[Wikipedia:London|London]] : {{Wiki|Oxford}} Univ. Press, 1931:p. 246) | ||

| − | + | CG1:24<br/> | |

| − | + | IV. The [[Buddha]] inherited this [[traditional]] [[Indian]] quest for [[knowledge]] . | |

| − | |||

| − | + | :A. The [[Buddhist]] quest {TEI:[1]} for [[knowledge]] shared three important [[characteristics]] with the quest that was expressed in the [[Wikipedia:Upanishads|Upanishads]]. This [[knowledge]] was intended to bring {{Wiki|unity}} {and [[peace]] of [[mind]]} to three areas of [[life]] : | |

| − | + | [[File:Nanda devatas.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | |

| + | ::1. External [[reality]] . {[[macrocosm]]} {Objectivity—[[Truth]] 1} | ||

| + | ::2. The [[self]] . {[[microcosm]]} {[[Emotions]] —[[Truth]] 2} | ||

| + | ::3. the [[ritual]] or [[symbolic]] practices that united the [[self]] with the [[world]] around it. {mesocosm} | ||

| − | + | :B. This quest for [[knowledge]] was not merely [[intellectual]] . It did not just change the way [[people]] [[thought]] or acted; it changed their very {{Wiki|identities}}. As the text of the [[Brihadaranyaka Upanishad]] says, "If a [[person]] [[knows]] 'I am [[Brahman]] ' in this way, he becomes the whole [[world]] ." {If a [[person]] identifies himself with the eternal [[universe]] he has overcome the {{Wiki|fear}} of [[death]] (and has [[peace]] -of-mind—the function of [[religion]] ) for the eternal [[universe]] is just that—eternal; in Spinozistic terms it is the [[intellectual]] [[love]] of G-D.} | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :C. Finally, this quest had to do with the challenge of [[overcoming]] {the {{Wiki|fear}} of} [[death]] , as in the story of the encounter between Nachiketas and [[Yama]] (the [[Lord]] of [[Death]] ) in the [[Katha Upanishad]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ::1. When Nachiketas was sent to meet the [[Lord]] of [[Death]] , the [[Lord]] of [[Death]] gave him a well-known [[teaching]] about the [[immortal]] [[soul]] : | |

| − | + | :::The [[wise one]] is not born and does not [[die]]; | |

| − | + | :::He does not come from anywhere; | |

| − | + | :::He does not become anyone. | |

| − | + | :::He is {{Wiki|unborn}}, eternal, primeval, and everlasting, | |

| − | + | :::And he is not killed when the [[body]] is killed. | |

[[File:16-6.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:16-6.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | + | ::::[[Katha Upanishad]] 1.18<br/>(Patrick Olivelle, trans., [[Wikipedia:Upanishads|Upanishads]], p. 237) | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ::2. With this [[knowledge]] , it was possible for Nachiketas to overcome the [[power]] of [[death]] . | |

| + | :D. We will see that the [[Buddha]] developed a very different [[idea]] of the [[nature]] of the [[self]] , but his goal was similar to the goal of Nachiketas. He wanted to know the [[nature]] of the [[self]] so that he could be released from the [[power]] of [[death]] . {{{Wiki|Spinoza}} 20:18} | ||

| − | + | ==Lecture Three== | |

| − | + | ===The [[Doctrine]] of [[Reincarnation]] === | |

| − | CG1:13 | + | CG1:13 |

| − | + | '''Scope''': | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Scope: | ||

[[File:194.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:194.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Along with the Indian quest for wisdom, the Buddha inherited a basic assumption about the nature of life: Human beings, like all other living creatures, lived not just one life, but came back into this world again and again in a continuous process of death and rebirth. This process is known in India as samsara, or "wandering" from one life to the next. At first glance, the idea of samsara may seem attractive, a chance to enjoy some of the things we missed in this life, but in ancient India, samsara was viewed as a burden. To escape this burden, a person had only two options: to perform {true} good actions (karma) and hope for a better rebirth or to renounce action altogether {see bodhisattva} and bring the cycle of death and rebirth to an end. | + | Along with the [[Indian]] quest for [[wisdom]] , the [[Buddha]] inherited a basic assumption about the [[nature]] of [[life]] : [[Human beings]], like all other living creatures, lived not just one [[life]] , but came back into this [[world]] again and again in a continuous process of [[death]] and [[rebirth]] . This process is known in [[India]] as [[samsara]] , or "wandering" from one [[life]] to the next. At first glance, the [[idea]] of [[samsara]] may seem attractive, a chance to enjoy some of the things we missed in this [[life]] , but in [[ancient]] [[India]] , [[samsara]] was viewed as a [[burden]]. To escape this [[burden]], a [[person]] had only two options: to perform {true} [[good actions]] ([[karma]] ) and {{Wiki|hope}} for a better [[rebirth]] or to {{Wiki|renounce}} [[action]] altogether {see [[bodhisattva]] } and bring the cycle of [[death]] and [[rebirth]] to an end. |

| − | {Cash value of reincarnation: | + | {Cash value of [[reincarnation]] : |

| − | + | :1. The [[belief]] in being [[reborn]] evokes a close, personal, [[loving]] relationship (I-thee) with all [[life]] [[forms]] (the worm you see could be your father [[reborn]]). Also it evokes the [[knowledge]] that everything, animate and [[inanimate]], is made of One Eternal [[Substance]]. | |

| − | + | :2. Pedagogical; it is an incentive to true good {{Wiki|behavior}} in order to be [[reborn]] to a higher station.} | |

| − | CG1:38 & 39 | + | CG1:38 & 39<br/> |

| − | + | III. If [[samsara]] is considered fundamental and is also a [[burden]], how can a [[person]] deal with it? The answer is to follow the law of [[karma]] , the law that governs the passage from one [[life]] to the next. {[[Good and bad]] are [[subjective]] terms; furthermore, in Spinozism there is no 'free-will and therefore no praise-no blame; Spinozism differs with the '[[karma]] ' {{Wiki|hypothesis}}.} | |

| − | III. If samsara is considered fundamental and is also a burden, how can a person deal with it? | ||

| − | |||

[[File:Timthu.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Timthu.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | + | :A. The [[word]] [[karma]] means "[[action]]," particularly the kind of [[moral]] [[action]] that affects a person's [[fate]] in a {{Wiki|future}} [[life]] . | |

| + | ::l. According to the law of [[karma]] , [[good actions]] bring a good [[rebirth]] in a {{Wiki|future}} [[life]] , and bad [[actions]] bring a bad [[rebirth]] . {See no free-will.} | ||

| + | ::2. [[Rebirth]] can generally take place in one of six [[realms]] : as a [[god]] , [[demigod]] , [[human being]], [[ghost]] , [[animal]] , or [[spirit]] in [[hell]] . These [[realms]] are vividly displayed in textbooks and paintings to show the punishments that confront evildoers in {{Wiki|future}} [[lives]]. | ||

| − | + | :B. The law of [[karma]] allows two strategies to deal with the problem of [[samsara]] . | |

| + | ::1. According to the ordinary norm (followed by most [[Indian]] [[people]]), a [[person]] attempts to perform good [[action]] to achieve a better [[rebirth]] , such as [[rebirth]] in [[heaven]]. This [[rebirth]] , like all the results of [[karma]], is [[impermanent]] {transitory}. | ||

| + | ::2. According to the [[extraordinary]] norm (followed by only a few [[religious]] specialists), a [[person]] attempts to perform no [[action]] {renunciator violates [[duty]] and is dysfunctional}, either good or bad. The goal is not a better [[rebirth]] , but no [[rebirth]] at all. The [[state]] of no [[rebirth]] , called [[moksha]] ([[liberation]] ) or prinirvana, is [[permanent]]. Once a [[person]] has achieved this [[state]], there is no return in the cycle of [[death]] and [[rebirth]] . | ||

| + | [[File:NatsuYasumi 029.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | :::[[Nirvana]] means '[[cessation of suffering]] ', the goal of [[Buddhist]] [[life]]<br/>{[[Nirvana]] is {{Wiki|equivalent}} to [[Spinoza's]] [[peace]]-of-[[mind]] (acquiescence of [[spirit]] or [[mind]]).} | ||

| − | + | :C. With the two norms come two {{Wiki|distinctive}} styles of [[life]] in [[Indian]] [[society]]. | |

| + | ::1. [[People]] who follow the ordinary norm situate themselves in a network of duties and responsibilities. They are mothers or fathers, [[teachers]] or students, {{Wiki|priests}} or [[kings]], and they are [[bound]] by the {{Wiki|rules}} that govern each of these {{Wiki|social}} roles. | ||

| + | ::2. [[People]] who follow the [[extraordinary]] norm "{{Wiki|renounce}}" these duties and give up their established roles in [[Indian]] [[society]]. The renunciants (sannyasls or bhiikshus and [[bhikshunis]]) have few possessions, often beg for their [[food]] , and live [[lives]] of deliberate [[simplicity]] to escape the network of [[karma]] that ties them in the cycle of [[samsara]] . | ||

| − | + | :D. When Sldhartha [[Gautama]] left the palace and became a wandering [[ascetic]] {to find [[enlightenment]] }, he chose to follow the [[extraordinary]] norm in the {{Wiki|hope}} of freeing himself from the cycle of [[death]] and [[rebirth]] . | |

| − | + | [[File:OriginalBuddha.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[File: | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | From W. Norman Brown's "Man in the [[Universe]] "; ISBN: 0520001850; Page 39. | |

| + | :The [[Wikipedia:Bhagavad Gita|Bhagavad Gita]] draws heavily upon the [[Wikipedia:Upanishads|Upanishads]] and the [[Vedas]] and some other kinds of [[thinking]] as well, which are not clearly identifiable. It is not consistent in its viewpoint, but [[knows]] and uses {{Wiki|monistic}} [[ideas]], [[dualistic]] [[ideas]], {{Wiki|theistic}} [[ideas]]. It accepts the [[doctrine]] of [[rebirth]] and the effect of one's acts in determining the [[conditions]] of [[rebirth]] . It condemns [[desire]] and teaches [[renunciation]] in the [[name]] of [[God]] {G-D}. [[Release]] from [[rebirth]] may be obtained through the performance of [[deeds]] without [[attachment]] to the results of the [[deeds]], that is through the performance of them selflessly, without any [[emotional]] accompaniment, merely because one is doing his [[duty]] {[[virtue]] }. Higher than this way to {{Wiki|salvation}} is the way of [[knowledge]] , more difficult to achieve—only the rare [[person]] can expect to succeed through it {[[intellectual]] [[love]] of G-D}. But the most feasible way is that of [[loving devotion]] ([[bhakti]] ) to [[God]] {G-D}. This is available to all, not merely to the ironwilled [[devotee]] of [[duty]] or to the superintellectual [[metaphysician]] , but to the lowly, the unsophisticated, the [[people]] of modest [[intelligence]]. Those who practice such [[devotion]] [[Krishna]] {G-D} will accept. The simple [[heart]] is enough. By means of [[devotion]] one can gain the fullest [[knowledge]] , can know G-D, can win to Him. Such a one, in fact, has a special advantage. "I am the same to all [[beings]]," says [[Krishna]], "there is no one either hateful to me or dear; but those who adore me with [[loving devotion]], they are in me and I too in them". | ||

| − | + | ==Lecture Four== | |

| − | [[ | + | ===The Story of the [[Buddha]] === |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

CG1:16 | CG1:16 | ||

| − | + | '''Scope''': | |

| − | |||

| − | + | {{Wiki|Historians}} generally agree that [[Siddhartha Gautama]] was born in a princely [[family]] in northern [[India]] about the year 566 B.C.E. As a young man, he gave up [[life]] in the palace and set out to escape the cycle of [[death]] and [[rebirth]] . After several difficult years of study and practice, he "woke up." not only to the [[cause]] of [[suffering]] but to its final [[cessation]] . He then wandered the roads of [[India]] , [[gathering]] together a group of [[disciples]] and establishing a pattern of [[discipline]] for the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|community}}. Finally, at about the age of eighty, he lay down and passed gently from the cycle of [[death]] and [[rebirth]] . With the simple events of the [[Buddha]] 's [[life]] as a guide, [[Buddhists]] have developed a rich [[tradition]] of stories and {{Wiki|legends}} that tell us not only how they have understood the founder of their [[tradition]] , but how they have built [[lives]] of [[wisdom]] and freedom for themselves. | |

| − | Historians generally agree that Siddhartha Gautama was born in a princely family in northern India about the year 566 B.C.E. As a young man, he gave up life in the palace and set out to escape the cycle of death and rebirth. After several difficult years of study and practice, he "woke up." not only to the cause of suffering but to its final cessation. He then wandered the roads of India, gathering together a group of disciples and establishing a pattern of discipline for the Buddhist community. Finally, at about the age of eighty, he lay down and passed gently from the cycle of death and rebirth. With the simple events of the Buddha's life as a guide, Buddhists have developed a rich tradition of stories and legends that tell us not only how they have understood the founder of their tradition, but how they have built lives of wisdom and freedom for themselves. | ||

| − | Book I:3 - Spinoza's "On the Improvement of the Understanding"—Way to wisdom | + | [[Book]] I:3 - [[Spinoza's]] "On the Improvement of the Understanding"—Way to [[wisdom]] . |

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Spinoza's]] quest for [[enlightenment]] is {{Wiki|equivalent}} to The [[Buddha]] 's quest. | |

| + | [[File:00buddha513.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | :[1] (1:1) After [[experience]] had [[taught]] me that all the usual surroundings of {{Wiki|social}} [[life]] are vain and futile; [[seeing]] that none of the [[objects]] of my {{Wiki|fears}} contained in themselves anything either good or bad {[[subjective]] terms}, except in so far as the [[mind]] is affected by them, I finally resolved to inquire whether there might be some real good {G-D} having [[power]] to {{Wiki|communicate}} itself, which would affect the [[mind]] singly, to the exclusion of all else: whether, in fact, there might be anything of which the discovery and [[attainment]] would enable me to enjoy continuous, supreme, and unending [[happiness]] {better °PcM}. | ||

| − | + | :[3] (3:1) I therefore [[debated]] whether it would not be possible to arrive at the new [[principle]] {Foundation Rock}, or at any rate at a {{Wiki|certainty}} concerning its [[existence]], without changing the conduct and usual plan of my [[life]] ; with this end in view I made many efforts, but in vain. (3:2) For the ordinary surroundings of [[life]] which are esteemed by men (as their [[actions]] testify) to be the [[highest]] good, may be classed under the three heads—Riches, [[Fame]] , and the [[Pleasures]] of [[Sense]] : with these three the [[mind]] is so absorbed that it has little [[power]] to reflect on any different good. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Lecture Five | + | ==Lecture Five== |

| − | + | ===All {Most} is [[Suffering]] === | |

| − | {See | + | CG1:16 |

| + | {See [[definition]] of '[[suffering]] '. Important.} | ||

| − | Scope: | + | '''Scope''': |

| − | Buddhist tradition tells us that the Buddha rose from the seat of his awakening and walked to a deer park in Sarnath, outside the city of Banaras, where he gave his first sermon. This event is called the first "turning of the wheel of dharma [teaching]." Accounts of the Buddha's teaching begin with the simple claim that "All is suffering." People who come to the Buddhist tradition for the first time often interpret this to mean that the Buddha was pessimistic and devalued human life. Buddhists say that he was not pessimistic but realistic. To see the world through Buddhist eyes, the first and most important step is to understand how this simple claim about suffering leads not to pessimism but to a realistic assessment {knowing or attributing to G-D the chain of natural causes and their natural effects and the knowledge that things could not come to pass different than they are} of life's difficulties and to a sense of liberation and peace {of mind, nirvana} | + | [[Buddhist]] [[tradition]] tells us that the [[Buddha]] rose from the seat of his [[awakening]] and walked to a [[deer park]] in [[Sarnath]] , outside the city of [[Banaras]], where he gave his [[first sermon]]. This event is called the first "turning of the [[wheel]] of [[dharma]] ([[teaching]])." Accounts of the [[Buddha]] 's [[teaching]] begin with the simple claim that "All is [[suffering]] ." [[People]] who come to the [[Buddhist]] [[tradition]] for the first [[time]] often interpret this to mean that the [[Buddha]] was {{Wiki|pessimistic}} and devalued [[human]] [[life]] . [[Buddhists]] say that he was not {{Wiki|pessimistic}} but {{Wiki|realistic}}. To see the [[world]] through [[Buddhist]] [[eyes]] , the first and most important step is to understand how this simple claim about [[suffering]] leads not to [[pessimism]] but to a {{Wiki|realistic}} assessment {[[knowing]] or attributing to G-D the chain of natural [[causes]] and their natural effects and the [[knowledge]] that things could not come to pass different than they are} of [[life]] 's difficulties and to a [[sense]] of [[liberation]] and [[peace]] {of [[mind]], [[nirvana]] }. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ====Lecture 5 - CG1:5:21 & 22.==== | |

| − | + | II. In the "[[Discourse]] on the Turning of the [[Wheel]] of [[Dharma]] (Dhammacakappavattana [[Sutta]] ), the [[traditional]] summary of the [[Buddha]] 's [[first sermon]], the [[Buddha]] 's [[teaching]] is summarized in [[Four Noble Truths]] . | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :A. The [[Four Noble Truths]] are: | |

| − | + | ::1. The [[truth]] of [[suffering]] ([[dukkha]] ) {[[caused]] by [[nothing]] being permanent;but moments of [[emotion]] are real} | |

| − | + | ::2. The [[truth]] of the [[arising]] of [[suffering]] {due to [[ignorance]] and harmful [[desires]] } | |

| − | + | ::3. The [[truth]] of the [[cessation of suffering]] (also known as [[nirvana]] {[[peace]] of [[mind]]}) | |

| + | ::4. The [[Noble]] [[Truth]] of the [[path]] that leads to the [[cessation of suffering]] . | ||

| + | -------------- | ||

| + | S>1.6 The [[Four Noble Truths]] can be stated as follows: | ||

| + | [[File:10d2fd63.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | :1. that [[life]] in all the [[realms]] of [[rebirth]] is, by [[definition]], ultimately unsatisfactory, [[suffering]] ([[duhkha]]) | ||

| + | :2. that there is a [[reason]] for this [[suffering]] , an origination ([[samudaya]]) of it, which is connected to our ongoing [[desire]] , a [[thirst]] that we cannot assuage, a [[clinging]] to possessions, to persons, to [[life]] itself | ||

| + | :3. that there is, however, such a thing as freedom from or the [[cessation]] ([[nirodha]]) of this unsatisfactory [[state]], this [[suffering]] , which will come with the rooting out (rather than the mere assuagement) of that on- going [[thirst]] {[[Spinoza's]] view L5:V:A2—notice that [[suffering]] does not have to do with [[sorrow]] and [[pain]], but with loss of [[peace]] of [[mind]]; worrying about the [[sorrow]] and [[pain]]. Remedy.} | ||

| + | :4. that the way to do this is to practice the so-called [[Noble Eightfold Path]] | ||

| − | + | S<This [[Path]] (marga) is the same as the [[realization]] of the [[Middle Way]] , between the extremes of indulgence and asceticism, and it is for this [[reason]] that the [[Buddha]] often preached the [[Middle Way]] along with the [[Four Noble Truths]] .>S:32 | |

| + | ---------------------- | ||

| + | III. The [[truth]] of [[suffering]] {loss of [[peace]] of [[mind]]} is expressed in the simple claim that "All is [[suffering]] ." | ||

| − | + | :A. When [[people]] come to the [[Buddhist]] [[tradition]] for the first [[time]] , they often interpret this claim to mean that the [[Buddha]] was {{Wiki|pessimistic}}. Our job is to understand how this simple statement about [[suffering]] leads not to [[pessimism]] but to a [[sense]] of [[liberation]] and [[peace]] . | |

| − | + | :B. [[Traditional]] sources say that "All is [[suffering]] " in one of [[three ways]]. | |

| + | ::1. Dukkhu-[[dukkha]] ([[suffering]] that is obviously [[suffering]] ): some things [[cause]] obvious [[physical]] or [[mental]] [[pain]] {loss of an arm}. | ||

| + | ::2. Viparirnama-[[dukkha]] ([[suffering]] due to change): even the most [[pleasurable]] things [[cause]] [[suffering]] when they begin to change and pass away {beginning to see the arm wither}. | ||

| + | ::3. [[Samkhara]]-[[dukkha]] ([[suffering]] due to [[conditioned]] states):<br/>[[pleasurable]] things can [[cause]] [[pain]] even in the midst of the [[pleasure]], if the [[pleasure]] is based on an [[illusion]] about the [[nature]] of the [[object]] {[[substance]] abuse} or even about the [[nature]] of the [[self]] {excessive [[pride]] or [[self]]-[[confidence]]}. | ||

| + | [[File:024 n.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | :C. These three kinds of [[suffering]] {loss of [[peace]] -of-mind} can be illustrated by creating a [[parable]] about a car. | ||

| + | ::1. A car [[causes]] [[dukkha]] -[[dukkha]] if you drive it into the back of a bus. | ||

| + | ::2. A car [[causes]] viparinama-[[dukkha]] if you're [[attached]] to that car and drive it through a New [[England]] winter and watch it disintegrate in the snow and [[salt]]. | ||

| + | ::3. A car [[causes]] [[samkhara]]-[[dukkha]] if you think there is something in yourself or in the car that will be enhanced by [[attachment]] [being fully invested with all of your [[impermanent]] "I"] to the car. | ||

| − | + | :D. The significance of these three kinds of [[suffering]] {loss of [[peace]] -of-mind} can be explained by relating them to the three *'marks" of [[existence]]. | |

| − | + | ::1. Everything is [[suffering]] . | |

| + | ::2. Everything is [[impermanent]] {transitory}. | ||

| + | ::3. [[Nothing]] has any [[self]] , or "all is no {[[permanent]]} [[self]] " ([[anatta]] ). | ||

| + | -------- | ||

| + | S<3.2 SUFFERING, IMPERMANENCE, AND no {permanent} [[self]] | ||

| − | + | We have already seen (in 1.6) that [[suffering]] , or unsatisfactoriness {loss of [[peace]] of mind} (duhkha, [[Pali]] : [[dukkha]] ) was propounded as the first of the [[Four Noble Truths]] . [[Suffering]] figures also as the first of the three "marks," or "characteristics," of existence along with [[impermanence]] ([[anitya]] , [[Pali]] : [[anicca]] ), and no-[[Self]] , or the absence of a [[Self]] ([[anatman]] , [[Pali]] : [[anatta]] ). These three [[doctrines]] , of course, are closely interdependent. Things are "[[suffering]] ," that is, not finally satisfying, because they are [[impermanent]] : they do not last forever, or even for a moment, but are in a constant process of change; and partly because of this, there can be no [[Self]] , that is, no "abiding ego," no "unchanging me," and consequently no "mine.">S89 | |

| − | + | {For the small {{Wiki|interval}} of [[time]] involved to make a [[judgment]], I can know if I am '[[sorrowful]], 'bored', or '[[happy]] '. Whatever it is, with [[understanding]] I can have [[peace]] -of-mind and thus save [[suffering]] . [[Spinoza's]] Dictum.} | |

| − | + | :S<3.2.1 [[Impermanence]] | |

| + | [[File:17952-medium.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | :Many [[Buddhist texts]] touch on the theme of [[impermanence]] or on the momentariness of the elements of existence, the "[[dharmas]] " that in [[Nikaya]] [[Buddhism]] are the basic constituents of [[reality]] . The full implications of the [[Buddhist]] [[doctrine]] of [[impermanence]] , as we shall see, were not without their [[philosophical]] convolutions, and these were tackled differently by different schools and worked out even more fully in the [[Mahayana]] . At a basic level, however, [[impermanence]] always meant simply that all beings, all things, having arisen, pass away: they die.>S:89, 90 | ||

| + | ------------------ | ||

| + | IV. What do [[Buddhists]] mean when they say that there is no {[[permanent]]} [[self]] ? | ||

| − | + | :A. In [[traditional]] [[Buddhism]] , "no [[self]] " means that no [[permanent]] [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] continues from one [[moment]] to the next. [This is a basic [[doctrinal]] [[assertion]] in the [[Buddhist]] [[tradition]] .] | |

| − | + | :B. This claim poses an obvious problem: If there is no {[[permanent]]} [[self]] , what makes up the [[human]] [[personality]]? | |

| + | ::1. The answer to this question is: the [[personality]] is made up of five "[[aggregates]] " or [[skandhas]] , bundles of momentary [[phenomena]] , beginning with (a) material [[form]] ([[rupa]] ); (b) [[sensations]] ; (c) [[ideas]] {{{Wiki|data}} base}; (d) [[Wikipedia:Volition (psychology)|volition]] {decisions that are made, like a {{Wiki|computer}} does}; and then, finally, (e) [[consciousness]] ([[viññana]]), the [[consciousness]] that observes the flow of this causal {chained} process. | ||

| + | ::2. These five [[aggregates]] are only momentary, but they group together to give the [[illusion]] of [[permanence]], like the flow of a [[river]] or the flame of a candle. | ||

| + | ::{3. See Lecture 5- TB5:79.} | ||

| − | + | :C. If there is no {[[permanent]]} [[self]] , what is [[reborn]]? | |

| − | + | ::l. The answer is the "{{Wiki|stream}}" or "flame" of [[consciousness]] ([[viññana]]). | |

| + | ::2. Because of the causal continuity between moments in the flame. it is possible to say that I am the "same" [[person]] from one [[moment]] to the next {and do [[judge]] my very real-to-me [[emotional]] [[condition]] at any one [[moment]]}. | ||

| + | ::3. But when we look closely at the flame, we realize that it changes every [[moment]], and the [[idea]] that one [[moment]] is the same as another is [[nothing]] but an [[illusion]] . | ||

| − | + | V. Is this view of [[human]] [[life]] {{Wiki|pessimistic}}? | |

| − | + | :A. The [[doctrine]] of "no {[[permanent]]} [[self]] " helps us understand why the [[doctrine]] of [[suffering]] is not as {{Wiki|pessimistic}} as it seems. | |

| + | ::1. From a [[Buddhist]] {{{Wiki|eternity}}} point of view, it is simply {{Wiki|realistic}} to accept that the [[human]] [[personality]] and all of [[reality]] is constantly changing. | ||

| + | ::2. The [[cause]] of [[suffering]] is not the change {[[sorrow]] or [[joy]]} itself, but the {futile} [[human]] [[desire]] to hold on to things and keep them from {negatively} changing. | ||

| + | [[File:20100903-6.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | :B. When [[Buddhists]] look at the [[world]] through the lens of no {[[permanent]]} [[self]] , they do not approach it in a {{Wiki|pessimistic}} way. | ||

| + | ::1. They understand that if everything changes, then it is possible for everything to become new. | ||

| + | ::2. If they accept {understand [[Emptiness]] } the [[doctrine]] of [[suffering]] , it is possible to approach even the most difficult situations in [[life]] with a [[feeling]] of lightness and freedom {[[peace]] -of-mind}. | ||

| − | + | :C. This [[doctrine]] is also related in a very precise way to the quest for [[nirvana]] . | |

| + | ::1. In my lecture on the [[Indian]] [[understanding]] of [[reincarnation]] , I pretended that I was [[writing]] the [[phrase]] "I act" on the blackboard, then crossed it out piece by piece. | ||

| + | ::2. Now we can understand what it means for a [[Buddhist]] to cross out the [[word]] "I." [[Buddhists]] can begin to erase this [[word]] by [[realizing]] that there is no [[permanent]] [[self]] to hold onto or {{Wiki|protect}}. | ||

| + | ::3. Just a hint of this [[realization]] is enough to start unraveling the chain of [[causes]] that bind [[people]] to the cycle of [[samsara]] and get them moving on the [[path]] to [[nirvana]] . | ||

| − | + | ====Lecture 5 - TB1:81 & 82.==== | |

| − | + | And this is about as deep as you can go into the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|concept}} of [[suffering]] . When they say that "All is [[suffering]] ," they mean, of course, that some things are [[painful]] {because of the loss of [[peace]] of [[mind]]; this type of [[pain]] can be mitigated by [[understanding]].}. They mean also that some things are [[impermanent]] ; that all things are [[impermanent]] and pass away. But what they mean in the most fundamental [[sense]] is that there is no [[permanent]] [[reality]] that gives anything any [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] that endures from one [[moment]] to the next. It's the great [[Buddhist]] [[doctrine]] of "no {[[permanent]]} [[self]] ." So, the question that we posed at the very beginning of our [[discussion]] about [[suffering]] —this question about [[pessimism]] —comes down to the [[doctrine]] of "no {[[permanent]]} [[self]] ." Are [[Buddhists]] {{Wiki|pessimistic}} when they say that there is no {[[permanent]]} [[self]] ? That's the question. | |

| + | [[File:2707.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | In a way, you could say that they are, because obviously there are lots of things that we hold on to in this [[world]] that we really like, that are associated in one way or another with this [[personality]] we're terribly fond of and anxious to {{Wiki|protect}}. And when that's stripped away it begins to [[feel]] like a negative [[experience]]; it can be harsh in some kinds of situations. | ||

| − | + | But it doesn't take too much [[thought]] , I think, to realize that it's not so much {{Wiki|pessimistic}} as it is {{Wiki|realistic}}. The [[truth]] is, we change. [[Life]] passes. The [[experiences]] of six months ago or ten years ago are gone, and if we try to hold on to them they're going to [[cause]] us some kind of [[suffering]] . | |

| − | + | It's this [[realization]] {assessment, [[understanding]]} that things are [[impermanent]] {because we are all a part of an [[infinite]] {{Wiki|organism}} (G-D) and the interaction of the parts change (or deteriorate) each other}, and the ability to let go of stuff that has changed and become part of our {{Wiki|past}} that makes the [[doctrine]] of [[suffering]] buoyant, [[light]] , and easy {to achieve [[peace]] of [[mind]]}, and can be expressed in one way or another in that exquisite [[smile]] the [[Dalai Lama]] brings to so many of his teachings. | |

| − | + | To [[recognize]] that there is no {[[permanent]]} [[self]] , in the end, is not to lose anything important. It's simply to let go of the [[frustration]] and the [[attachment]] that brings [[suffering]] to this [[world]] . And in that [[sense]] , this [[extraordinary]] claim, "All is [[suffering]] ," becomes a claim about freedom, about buoyancy, about lightness, and about, in the end, [[nirvana]] . [[Nirvana]] will be the topic of our next lecture. | |

| − | + | ====Lecture 5 - TB1:79.==== | |

| − | + | {[[The First Noble Truth]] - The [[truth]] of [[suffering]] [[caused]] by [[nothing]] being [[permanent]].} | |

| − | + | These [[aggregates]] are only momentary; think of them like flickers on a video screen {one frame of a moving-picture roll of film}. They're only momentary {derivatives, infinitesimals }, but they group together to give an [[illusion]] of some kind of continuity or [[permanence]]. [[Buddhists]] [[traditionally]] use two comparisons to express this [[idea]]. One is to say that the [[personality]] is like the {{Wiki|stream}} of a [[river]] , like the flow of a {{Wiki|stream}}. In fact the [[word]] "{{Wiki|stream}}" is often used to [[name]] the [[personality]]: the [[word]] is [[santana]]. The [[personality]] is [[nothing]] but a {{Wiki|stream}} of [[aggregates]] flowing through the [[world]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Another comparison they use—quite common—is to think of the [[personality]] as a flame, as a [[fire]]. This is actually useful because it also suggests at the same time that the [[personality]] is "burning" in a [[painful]] way. It's a [[fire]] that we fuel by all of the [[karma]] that we produce; all of the [[actions]] that we perform to achieve a certain goal or to avoid a certain [[unhappy]] [[state]]. All of that [[karma]] is like throwing logs on a great bonfire, and it burns—burns constantly—changing from one [[moment]] to the next. So, [[Buddhists]] think of the [[personality]] as flowing like a [[river]] and burning like a [[fire]]. | |

| − | + | ==Lecture Six== | |

| − | + | ===The [[Path]] to [[Nirvana]]=== | |

| − | + | CG1:24 | |

| − | + | [[File:2944293 300.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | |

| − | + | '''Scope''': | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | After describing the [[truth]] of [[suffering]] , the [[Buddha]] went on to describe the origin of [[suffering]] , the [[cessation of suffering]] , and the [[path]] that leads to the [[cessation of suffering]] . The [[cessation of suffering]] is also called [[nirvana]] , the "blowing out" of [[desire]] . Like the {{Wiki|concept}} of [[suffering]] , [[nirvana]] can seem very negative at first. In some respects, this is inescapable, [[Nirvana]] constitutes the definitive end of the cycle of [[rebirth]] . But [[nirvana]] does not need to be viewed in a purely negative way, especially when it is understood not just as the end of [[life]] , but as [[realization]] {the [[intellectual]] [[love]] of G-D} that infuses and enlivens the [[Buddha]] 's [[experience]] from the [[time]] of his [[awakening]] to the [[moment]] of his [[death]] . | |

| − | + | '''Outline''' | |

| − | + | I. The second [[Noble]] [[Truth]] is the origin or [[arising]] of [[suffering]] . | |

| − | + | :A. The origin of [[suffering]] is explained by a causal sequence known as the "twelvefold chain of [[dependent arising]] " ([[paticca-samuppada]]). | |

| − | + | :B. The most important links in this chain show a process that leads from [[ignorance]] to [[birth]]. | |

| + | ::1. [[Ignorance]] {due to [[knowledge]] of the First Kind} leads to {harmful, irrational} [[desire]] . | ||

| + | ::2. {Irrational} [[Desire]] leads to [[birth]]. | ||

| − | + | :C. To understand what [[Buddhists]] have in [[mind]] when they make this series of connections, you might take a glossy advertisement from a magazine and ask what kinds of [[illusions]] it fosters, what kinds of [[desires]] it is meant to arouse, and what comes into being as a result of those [[desires]] . Most of these [[desires]] are quite benign, of course, but they feed the creative process that, for [[Buddhists]] leads to more [[death]] and [[rebirth]] . | |

| − | + | :D. The most fundamental [[form]] of [[ignorance]] , of course, is that "I" constitute a [[permanent]] [[ego]] {an "I-it" [[relation]]} that needs to be fed by new and desirable [[experiences]] or new and desirable [[objects]]. | |

| + | [[File:46cc81e.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | II. The third [[Noble]] [[Truth]] is [[cessation]] , or [[nirvana]] . | ||

| − | + | :A. When someone starts to cultivate an [[awareness]] of no {[[permanent]]} [[self]] and strips away the [[desires]] that feed the [[fire]] of [[samsara]] , it is possible eventually for the [[fire]] of [[samsara]] to burn out. | |

| + | ::1. This is not easy, and it may take many lifetimes. | ||

| + | ::2. But it is possible for anyone to achieve the same [[cessation]] of [[samsara]] that was [[experienced]] by the [[Buddha]] himself. | ||

| − | + | :B. This [[cessation]] is known by the [[name]] [[nirvana]] ([[Pali]] : [[nibbana]] ). | |

| + | ::1. [[Nirvana]] means to "blow out," like the flame of a candle. | ||

| + | ::2. It can be understood as the "blowing out" of [[desire]] , the "blowing out" of [[ignorance]] , or the "blowing out" of [[life]] itself, if [[life]] is understood as the [[constant]] cycle of [[death]] and [[rebirth]] . | ||

| + | ::3. [[Nirvana]] comes at two moments: at the [[moment]] of [[awakening]] , when the [[Buddha]] understood that he was no longer adding fuel to the [[fire]] of his [[personality]], and at the [[moment]] of [[parinirvana]] , when the [[fire]] of his [[personality]] finally flickered out. | ||

| + | ::4. These two moments are called "[[nirvana]] with residues" and "[[nirvana]] without residues." | ||

| − | + | :C. Like the {{Wiki|concept}} of [[suffering]] , [[nirvana]] seems at first to be quite negative. [[People]] often ask: If [[nirvana]] is just an [[experience]] of [[cessation]] , why do [[Buddhists]] find it so desirable? | |

| + | ::1. The first way to answer this question is to understand that [[nirvana]] forces us to take seriously the negative [[Indian]] [[Wikipedia:evaluation|evaluation]] of [[samsara]] . If [[samsara]] really is something to be avoided, then the most positive thing to do about it is simply to negate it, to bring it to an end. [[Nirvana]] is this {{Wiki|negation}}. | ||

| + | ::2. This view of [[nirvana]] as [[cessation]] stands in sharp contrast to the [[Wikipedia:Judaism|Jewish]] and [[Christian]] {{Wiki|concept}} of a [[God]] who created the [[world]] out of [[nothing]] . According to [[Wikipedia:Judaism|Jewish]] and [[Christian]] [[tradition]] , [[God]] once faced "[[nothing]] " and made something come to be. The [[Buddha]] did the opposite. He faced a situation in which [[death]] and [[rebirth]] had been going on from [[time]] without beginning and found a way to bring one small part of it to an end. {{{Wiki|Spinoza}} posited G-D.} | ||

| + | ::3. A second way to explain the appeal of [[nirvana]] is to understand that the [[experience]] of [[nirvana]] is not limited just to the [[moment]] of the [[Buddha]] 's [[death]] . The [[Buddha]] also [[experienced]] [[nirvana]] at the [[moment]] of his [[awakening]] , when he knew that he was no longer [[bound]] by the [[ignorance]] and [[desire]] that fuel [[samsara]] . | ||

| + | ::4. When it is understood this way, [[nirvana]] is not just the [[cessation]] of [[life]] . It is a [[quality]] of [[mind]] or a [[state of being]] that characterized the [[Buddha]] 's [[life]] in the forty years between his [[awakening]] and his [[parinirvana]] . | ||

| + | ::5. During this [[time]] , the [[Buddha]] exemplified many positive [[characteristics]]: He was [[peaceful]], [[wise]], unattached {[[enlightened]] }, and free. We might also [[imagine]] that he was able to act with a certain spontaneity and [[clarity of mind]], perhaps even with a certain [[compassion]] for the [[suffering]] of others. | ||

| − | + | III. The [[Fourth Noble Truth]] is the [[Path]] . | |

| − | + | :A. The [[Path]] to [[Nirvana]] is often divided into eight categories: [[right understanding]] , [[right thought]] , [[right speech]] , [[right action]] , [[right livelihood]] , [[right effort]] , [[right mindfulness]] , and [[right concentration]] . {TEI[17]} | |

| − | + | :B. The [[logic]] of the [[path]] is clearer, however, if we reduce these eight categories to three: | |

| + | ::1. [[sila]] , or [[moral]] conduct | ||

| + | ::2. [[samadhi]], or [[mental]] [[concentration]] | ||

| + | ::3. [[pañña]], or [[wisdom]] . | ||

| + | [[File:5lk.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | :C. [[Buddhist]] [[lay people]] observe five [[moral]] [[precepts]] ([[sila]] ): no {{Wiki|killing}}. no [[stealing]] , no {{Wiki|lying}}, no abuse of {{Wiki|sex}}, and no drinking [[intoxicants]]. | ||

| − | + | :D. [[Monks]] observe five more, [[including]] the restrictions that they cannot eat after twelve noon, cannot [[sleep]] on soft beds, and cannot handle {{Wiki|gold}} or {{Wiki|silver}}. | |

| − | + | :E. [[Buddhist]] practitioners engage in [[mental]] [[concentration]] (samadihi) to focus and clarify the [[mind]]. | |

| − | + | :F. They also cultivate [[wisdom]] ([[pañña]]) or the [[understanding]] of no {[[permanent]]} [[self]] . | |

| − | + | ::TB1:97 | |

| − | + | :::Finally, the third thing that you want to do—in a lot of ways this is the most important because it really is the foundation of all other [[Buddhist]] virtues—is to cultivate [[wisdom]] {[[understanding]]}. Here the [[word]] is [[pañña]]. It actually comes from the great [[Sanskrit]] [[root]] "jna," which is {{Wiki|cognate}} with our "k-nowledge," with the "k-now" of "k-nowledge." So, pajna, [[pañña]], is in a [[sense]] , "prognosis"—to know the [[nature]] of the [[world]] and to know where it's going {chain} so that you yourself can become [[detached]] from {[[enlightened]] —organically [[interdependent]] with} it and begin the process that leads to [[nirvana]] {PcM}. What do you know? Of course, particularly, the [[reality]] of "no {[[permanent]]} [[self]] ." | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :::So, it's these three things: [[sila]] , samadihi, and [[pañña]], that lead you eventually to the [[experience]] of [[nirvana]] {[[peace]] of [[mind]]}. | |

| − | + | :G. These three modes of [[discipline]] are meant to avoid the [[karma]] that will lead a [[person]] to difficult and [[dangerous]] [[forms]] of [[rebirth]] . They also meant to cultivate the qualities of [[wisdom]] and [[detachment]] {[[enlightenment]] } that eventually led to the [[Buddha]] 's [[experience]] of [[awakening]] . | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | ==Lecture Twelve== | ||

| + | ===[[Emptiness]] === | ||

CG1:45 | CG1:45 | ||

| − | + | {Think of '[[emptiness]] ' as a [[mind]] [[empty]] of (false) [[subjective]] [[thoughts]] ; but instead, filled with (true) [[subjective]] and [[objective]] [[thoughts]] —with [[understanding]]. See — [[pure]] [[consciousness]]. I dislike the [[word]] '[[emptiness]]' because '[[EMPTINESS]] of all [[thought]]' implies a robot—no [[emotion]], no [[understanding]].} | |

| − | + | [[File:Afnn.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | |

| − | + | '''Scope''': | |

| − | (true) subjective and objective | ||

| − | I dislike the word 'emptiness' because 'EMPTINESS of all thought' implies a robot—no emotion, no understanding.} | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | At the [[heart]] of [[Mahayana]] practice lies the {{Wiki|paradoxical}} and elusive {{Wiki|concept}} of [[Emptiness]] . When they speak about the [[nature]] of [[reality]] , [[Mahayana texts]] claim that [[nothing]] [[exists]] in its [[own]] right. They say, in other words, that everything is "[[empty]]" of [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] {because it is constantly changing}. Like many [[Buddhist]] [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]], [[Emptiness]] seems at first to be very negative, but the [[Mahayana]] [[tradition]] claims that it is exactly the opposite. [[Mahayana texts]] insist that "everything is possible for someone for whom [[Emptiness]] is possible." To understand how this can be true, we need to consider the [[doctrine]] of [[two truths]]: | |

| − | + | ------------- | |

| + | :{[[Truth]] 1—objective reference - non-personal}<br/>While it may be true that [[nothing]] [[exists]] in its [[own]] right from the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] {{{Wiki|eternity}}}point of view; | ||

| − | + | :{[[Truth]] 2—true [[subjective]] reference- personal}<br/>it is possible {necessary} to take the ordinary categories of [[life]] seriously in a provisional and [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] way {chain of natural [[causes]] with its joys and sorrows}. | |

| − | + | :{See [[definition]] of '[[suffering]] '. Important in [[understanding]] [[Truth]] 1 and [[Truth]] 2 and their {{Wiki|synthesis}}.} | |

| + | ----------------- | ||

| + | {{Wiki|Learning}} to distinguish {reconciling, synthesizing [[Truths]] 1 & 2} between the [[Wikipedia:Absolute (philosophy)|ultimate]] and [[Wikipedia:Convention (norm)|conventional]] {everyday} perspectives is one of the most important and liberating skills {in achieving [[peace]] -of-mind} in the practice of the [[Mahayana]] {and is [[Spinoza's]] Dictum's {{Wiki|equivalent}}}. | ||

| − | + | {Everything is "[[empty]]" of [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] because it is constantly changing but at any one instant (dP/dt) there is a real and important change in the {{Wiki|probability}} of your perpetuating yourself (conatus) that results in an [[emotion]] that is real at that instant (you are being run down by a car, a loved one [[dies]] ([[sorrow]] = -dP/dt); you escape being run down, you have a new healthy child ([[joy]] = +dP/dt). [[Knowing]] G-D ({{Wiki|equivalent}} to what the [[Buddha]] [[taught]]) means [[understanding]] [[Truth]] 1. You can then achieve [[Peace]] of [[Mind]] in either [[sorrow]] or [[joy]] by [[understanding]] the cause(s); or, if beyond your [[knowledge]] , by a leap-of-[[faith]] ({{Wiki|hypothesis}}) attributing the [[understanding]] to the [[infinite]] [[intellect]] of G-D; i.e. the chain of natural [[causes]] and their natural effects and the [[knowledge]] that things could not have been different than they are. [[Causes]] are in G-D, are knowable now, or will be known some day. Example—losing an arm. Thus, [[Truths]] 1 & 2 are reconciled and synthesized and result in having great {{Wiki|practical}} value—the possibility of achieving a modicum of [[Peace]] of [[Mind]] .} | |

| − | + | {I change '[[emptiness]] ' to '[[understanding]]' in order to better understand the [[teaching]]. [[Understanding]] things constantly change, helps taking (where possible) the momentary events too seriously and getting upset.} | |

| − | |||

| − | + | '''Outline''' | |

| − | + | I. The [[Mahayana]] introduced many important changes in the [[Indian]] [[Buddhist]] [[tradition]] , but none was as profound or as far-reaching as the {{Wiki|concept}} of [[Emptiness]] . | |

| + | [[File:87250-84352.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | :A. [[Emptiness]] challenged {[[understanding]] [[Truth]] 1} and undermined many of the rigid categories of [[traditional]] [[Buddhism]] {and mitigated [[suffering]] }. | ||

| − | + | :B. But it also introduced a new [[spirit]] of [[affirmation]] and possibility {of achieving [[peace]] of [[mind]]}. | |

| − | + | :C. A balanced [[understanding]] of [[Emptiness]] has to account for both its positive and its negative {{Wiki|dimensions}}. {Positive—knowing things constantly change ([[Truth]] 1); negative—not losing your [[peace]] -of-mind in the [[reality]] of [[Truth]] 2.} | |

| − | + | II. [[Emptiness]] can be understood as an extension of the [[traditional]] [[Buddhist]] [[doctrine]] of "no {[[permanent]]} [[self]] ." | |

| − | + | :A. In the [[Hindu]] [[tradition]] , particularly in the [[Wikipedia:Upanishads|Upanishads]], it was understood that each [[person]] has an enduring (eternal) [[self]] ([[atman]] ). TB1:181{3}. | |

| − | + | :B. The [[Theravada]] [[Buddhist]] [[tradition]] denies that there is any enduring [[self]] . | |

| + | ::1. According to the [[Theravada]] , the so-called "[[self]] " is made up of a series of momentary [[phenomena]] known as [[dhammas]] ([[Pali]] ) or [[dharmas]] ([[Sanskrit]] ). | ||

| + | ::2. These momentary [[phenomena]] give the [[illusion]] of continuity, like the moments of flowing [[water]] that make up the current of a [[river]] or the flickers of burning gas that make up the flame of a candle. TB1181{4}. | ||

| − | + | :C. The [[Mahayana]] takes a step further: It denies the [[reality]] of any enduring [[self]] and also denies the [[reality]] of the momentary [[phenomena]] that make up the flow of the [[personality]].<br/>{Spinozism differs on the {{Wiki|denial}} of the [[reality]] of the momentary [[phenomena]] . It concurs with [[Truth]] 2.} | |

| − | + | ::1. This [[Mahayana]] position is expressed by saying, that everything is "[[empty]]" (shunyna) of [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] ([[svabhava]] or [[atman]] ). | |

| + | ::2. The [[nature of all things]] is simply their "[[emptiness]] " ([[shunyata]] ) {i.e. constantly changing}. | ||

| − | + | :D. By rejecting the [[idea]] that the [[personality]] was made up real moments, the [[Mahayana]] completely reoriented the {{Wiki|conceptual}} framework of [[Buddhism]] . TB1181{6} | |

| − | + | From John S. Strong's "The [[Experience]] of [[Buddhism]] : Sources and Interpretations. [[Belmont]], [[California]]: Wadsworth, 1995; [[Chapter]] 3 - The [[Dharma]] : Some Perspectives of [[Nikaya]] [[Buddhism]] ; Page 87-88. | |

| + | [[File:90698 n.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | :It is customary in {{Wiki|speaking}} of the [[development]] of the [[Dharma]] to oppose the [[views]] of the [[Lesser Vehicle]] ([[Hinayana]] ) to those of the [[Greater Vehicle]] ([[Mahayana]] ). However since the term [[Hinayana]] was not used by [[Hinayanists]] but was a denigrative designation invented by [[Mahayanists]] for pejorative purposes, it sometimes happens that the [[word]] [[Theravada]] (the [[Tradition]] of the [[Elders]]) is used instead. But [[Theravada]] and [[Hinayana]] do not designate the same thing. The [[Theravada]] was, in fact, but one of many [[Hinayana]] schools (the [[traditional]] number was eighteen) which had varying [[views]] on a variety of issues. So as to retain this [[sense]] of breadth while avoiding the pejorative overtones explicit in the notion of a [[Lesser Vehicle]], I have chosen in this {{Wiki|anthology}}, to use the expression [[Nikaya]] [[Buddhism]] ([[Buddhism]] of the Schools) instead of [[Hinayana]] . This label is not without its [[own]] set of problems, but at least it was occasionally used by [[Buddhists]] themselves, and it is increasingly being adopted by [[scholars]] . | ||

| − | + | :Among the schools of [[Nikaya]] [[Buddhism]] , the [[Theravada]] is important because it is the only one to have survived as an institution and it now preponderates in [[Sri Lanka]] and {{Wiki|Southeast Asia}}. It also managed to have kept intact its [[canon]] of [[scriptures]] (written in the [[Pali]] [[language]] ), unlike the other [[Nikaya]] [[Buddhist]] schools, whose canons (written in [[Sanskrit]] ) have been only partially preserved. But the fuller preservation and readier accessibility of [[Theravada]] texts and [[traditions]] should not erase from our [[minds]] the historical importance of the other schools, for example, the [[Sarvastivadins]], the [[Mahasamghikas]], and the [[Pudgalavadins]], which had a tremendous influence on the [[development]] and [[direction]] of [[Buddhist]] [[doctrine]] . | |

| − | + | :For all their differences, however, the [[Nikaya]] [[Buddhist]] schools also held a large number of [[views]] in common. Thus, although we shall pay some [[attention]] to divergent opinions at the end of this [[chapter]], we shall focus first on the basic [[doctrines]] that held [[Nikaya]] [[Buddhism]] together. Secondly, as we shall see, many of these same basic [[Nikaya]] [[Buddhist]] [[doctrines]] were not abandoned by the [[Mahayana]] . To be sure, [[Mahayanists]] extended them, added to them, reinterpreted them, and critiqued them, but for the most part they did not fundamentally reject them. Many of the [[doctrines]] that follow, therefore, can be considered to be basic to the whole of [[Buddhism]] . | |

| − | + | ====Lecture 12 - TB1:181==== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | {1}. I {Prof. [[Eckel]]} have to say in passing that this is the {{Wiki|concept}} that I've spent most of my adult [[life]] studying. This is really where I put my feet down most firmly in the study of the [[Mahayana]] . So, I {{Wiki|present}} this to you not just with a kind of {{Wiki|theoretical}} [[interest]] but something that sort of strikes me in the gut. The [[doctrine]] of [[Emptiness]] , I think, in a lot of ways is one of the most profound and challenging [[religious]] [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] {that of achieving [[peace]] of [[mind]]} in the [[world]] , and one that if you can [[grasp]], if you can even just get a {{Wiki|taste}} of, will help you see not just the basic categories of [[Buddhism]] {and Spinozism}, page 182 but also lots of other important categories in [[life]] in a radically different way {[[Spinoza's]] Dictum}. | ||

| − | + | {2}. So, let's start out with a basic analysis of this {{Wiki|concept}}, of [[Emptiness]] . [[Emptiness]] can be understood, I think, as a radical extension of the {{Wiki|concept}} of "no {[[permanent]]} [[self]] " in [[traditional]] [[Buddhism]] . This is a {{Wiki|concept}} that we've already talked about. And let's lay it out for ourselves somewhat methodically. We ask ourselves, now, as the lectures are moving slowly through the study of [[Buddhism]] , "What [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] of the [[self]] have we already learned?" | |

| + | [[File:Bjtk090a.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | {3}. One, I suppose, would come from the [[Wikipedia:Upanishads|Upanishads]], that old [[Hindu]] [[idea]] of the eternal [[self]] that's [[identical]] to [[Brahman]] {G-D}, and [[identical]] to the one [[reality]] that underlies the {{Wiki|unity}} {[[substance]]} of the diversity of this [[world]] . So, in the [[Hindu]] [[tradition]] , the [[self]] is [[identical]] to [[Brahman]] , and it is eternal and [[permanent]]. | ||

| − | + | {4}. The [[Theravada]] [[tradition]] expresses a [[traditional]] [[Buddhist]] view that undermines this old [[Hindu]] [[vision]] of the [[permanent]] or eternal [[self]] . In [[traditional]] [[Buddhism]] , there is [[nothing]] [[permanent]] that endures from one [[moment]] to the next, so [[traditional]] [[Buddhists]] say that there is no {[[permanent]]} [[self]] . There is no [[permanent]] [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] that endures from one [[moment]] to the next. All that we see in [[reality]] {[[Truth]] 2} is just a series of momentary [[phenomena]] , [[bound]] together to give the [[illusion]] of some kind of continuity, like the flickers in the flame of a candle {or one frame of a moving picture} or the moments, in the flow of a [[river]] {[[Truth]] 1}. | |

| − | + | {5}. So, the [[self]] , according to [[traditional]] [[Buddhism]] , was made up of a series of momentary [[phenomena]] known as [[dhammas]] in [[Pali]] , or as [[dharmas]] in [[Sanskrit]] . This is a use of the [[word]] [[dharma]] that we haven't talked about before; it's [[dharma]] as fundamental constituent of [[reality]] . So, the [[self]] in [[traditional]] [[Buddhism]] is simply a flow of momentary [[phenomena]] called [[dharmas]] . | |

| − | |||

| − | + | {6}. Now the [[Mahayana]] took a step further. They went beyond this [[traditional]] [[Buddhist]] [[idea]] of the [[self]] to deny the [[reality]] not just of an enduring [[self]] , but to deny the [[reality]] {JBYnote1} of the moments themselves. So, they said that these momentary [[phenomena]] , these [[dharmas]] , that make up the flow of [[life]] like the flickers in a candle flame are [[empty]] of [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]], [[empty]] of [[reality]] {Spinozism differs; [[proof]]—[[emotion]] the instant I put my hand into that flame}. That's the way they expressed this [[insight]] . All [[dharmas]] are [[empty]] of [[reality]] {S:358, divergent opinions}. | |

| + | [[File:Bodhgya-atue.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| + | {I posit the [[Mahayana]] {{Wiki|denial}} of the [[reality]] of the moments themselves [[as evidence]] that the [[human]] [[condition]] of their [[society]] was so terrible and hopelessly hopeless, that they defined (stipulated that) '[[reality]] ' meant '[[non-existence]]', as an {{Wiki|hypothesis}} to achieve [[peace]] -of-mind. This {{Wiki|hypothesis}} is little different than the Christian's salving crucifixion as a way to achieve [[peace]] -of-mind. See Mark Twain's "Little Story".} | ||

| − | + | III. The {{Wiki|concept}} of [[Emptiness]] has important negative {{Wiki|consequences}}. but it has a positive [[dimension]] as well. | |

| − | + | :A. If everything is [[empty]] of any real [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]], there can be no real difference between any two things. As a result, [[Mahayana texts]] often equate [[Emptiness]] with "[[non-duality]] {which is {{Wiki|equivalent}} to [[Spinoza's]] everything is in G-D; i.e. a part of G-D}." | |

| + | ::1. If everything is [[empty]], there can be no difference or "[[duality]]" between [[nirvana]] and [[samsara]] . and there can be no difference between ourselves and the [[Buddha]] . | ||

| + | ::2. This means that [[nirvana]] is right here, at this [[moment]] {this is the 'cash value' of [[Emptiness]] —[[Peace]] of [[Mind]] }, if we can only understand it correctly. It also means that we are already [[Buddhas]] if we understand that the [[nature]] of ourselves is no different from the [[nature]] of the [[Buddha]] {[[Spinoza's]] pantheism—everything is a part of G-D}, | ||

| − | + | :B. The [[bodhisattva]] does not turn away from [[nirvana]] purely for {{Wiki|altruistic}} [[reasons]]. | |

| − | + | ====Lecture 12 - TB1:184==== | |

| − | + | [[File:Buddha-478.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | |

| + | But you can see here now, when you confront the [[doctrine]] of [[Emptiness]] , that a [[bodhisattva]] doesn't come back just for {{Wiki|altruistic}} purposes. It's not just [[altruism]] that drives the [[bodhisattva]] back into this [[world]] . | ||

| − | + | Why? There isn't any difference between [[nirvana]] and [[samsara]] . And if there's no [[nirvana]] out there to seek that's different than what's going in this [[world]] , you can only find it here. You've got to come back. There's no place that you can escape from where we are right now. So, the [[bodhisattva]] , sure, is back in the [[world]] of [[samsara]] to help other [[people]], but the [[bodhisattva]] is also back here for [[reasons]] that have to do with the [[bodhisattva]] 's [[own]] [[awareness]] —the [[bodhisattva]] 's [[own]] [[sense]] of himself or herself {as an [[interdependent]], efficient-functioning part of an [[infinite]] {{Wiki|organism}}}; to know [[nirvana]] {[[peace]] of [[mind]]}, right here, in {[[understanding]]} the [[experience]] of [[suffering]] in this [[world]] . | |

| − | + | 1. In seeking [[nirvana]] , the [[bodhisattva]] finds that there is no [[nirvana]] apart from [[samsara]] . {All things are in G-D.} | |

| − | + | 2. This means that [[nirvana]] can be [[attained]] only in the context of [[samsara]] . | |

| − | + | :C. A correct [[understanding]] of [[Emptiness]] requires a [[balance]] between two different perspectives or "[[truths]]." | |

| + | ::1. Ultimately, all things are [[empty]] and [[nothing]] is real {real but {{Wiki|ephemeral}}, transitory}. | ||

| + | ::2. Conventionally; from the point of view of ordinary [[life]] , it is possible {necessary} to take things seriously {your child deathly ill}. | ||

| − | + | ====Lecture 12 - TB1:184-5==== | |

| − | |||