Difference between revisions of "Ekai Kawaguchi"

(Created page with "{{Nihongo|Ekai Kawaguchi 河口慧海|Kawaguchi Ekai}} (February 26, 1866 – February 24, 1945) was a Japanese Buddhist monk, famed for his fo...") |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

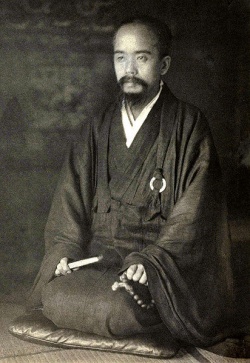

| − | {{Nihongo|[[Ekai Kawaguchi]] 河口慧海 | + | [[File:Ekai_Kawaguchi.jpg|thumb|250px|]] |

| + | {{Nihongo|[[Ekai Kawaguchi]] [[河口慧海]] [[Kawaguchi Ekai}} (February 26, 1866 – February 24, 1945) was a [[Japanese people|Japanese]] [[Buddhist monk]], famed for his four journeys to [[Nepal]] (in 1899, 1903, 1905 and 1913), and two to [[Tibet]] (July 4, 1900–June 15, 1902, 1913–1915), being the first recorded [[Japanese]] citizen to travel in either country.<ref name="Japanese_Embassy" /><ref>Hyer, Paul (1979). "Narita Yasuteru: First [[Japanese]] to Enter [[Tibet]]". ''[[Tibet]] Journal'' Vol. IV, No. 2, Autumn 1979, p. 12.</ref> | ||

| − | From an early age Kawaguchi, whose [[birth]] [[name]] was Sadajiro, was [[passionate]] about becoming a [[monk]]. In fact, his [[passion]] was unusual in a country that was quickly modernizing; he gave serious [[attention]] to the [[monastic]] [[vows]] of [[vegetarianism]], {{Wiki|chastity}}, and temperance even as other [[monks]] were happily [[abandoning]] them. As a result he became disgusted with the worldliness and {{Wiki|political}} corruption of the [[Japanese Buddhist]] [[world]].<ref>Berry 1989, p. 11-12</ref> Until March, 1891, he worked as the [[Rector (academia)|Rector]] of the [[Zen]] {{Nihongo|[[Gohyaku rakan]] Monastery|五百羅漢寺|Gohyaku-rakan-ji}} in {{Wiki|Tokyo}} (a large [[temple]] which contains 500 ''[[arhat|rakan]]'' icons). He then spent about 3 years as a [[hermit]] in [[Kyoto]] studying {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Buddhist texts]] and {{Wiki|learning}} [[Pali]], to no use; he ran into {{Wiki|political}} squabbles even as a [[hermit]]. Finding [[Japanese Buddhism]] too corrupt, he decided to go to [[Tibet]] instead, despite the fact that the country was officially off limits to all foreigners. | + | From an early age [[Kawaguchi]], whose [[birth]] [[name]] was [[Sadajiro]], was [[passionate]] about becoming a [[monk]]. In fact, his [[passion]] was unusual in a country that was quickly modernizing; he gave serious [[attention]] to the [[monastic]] [[vows]] of [[vegetarianism]], {{Wiki|chastity}}, and temperance even as other [[monks]] were happily [[abandoning]] them. As a result he became disgusted with the worldliness and {{Wiki|political}} corruption of the [[Japanese Buddhist]] [[world]].<ref>Berry 1989, p. 11-12</ref> Until March, 1891, he worked as the [[Rector (academia)|Rector]] of the [[Zen]] {{Nihongo|[[Gohyaku rakan]] Monastery|五百羅漢寺|Gohyaku-rakan-ji}} in {{Wiki|Tokyo}} (a large [[temple]] which contains 500 ''[[arhat|rakan]]'' icons). He then spent about 3 years as a [[hermit]] in [[Kyoto]] studying {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Buddhist texts]] and {{Wiki|learning}} [[Pali]], to no use; he ran into {{Wiki|political}} squabbles even as a [[hermit]]. Finding [[Japanese Buddhism]] too corrupt, he decided to go to [[Tibet]] instead, despite the fact that the country was officially off limits to all foreigners. |

| − | He left [[Japan]] for [[India]] in June, 1897, without a guide or map, simply buying his way onto a cargo boat. He had a smattering of English but did not know a [[word]] of {{Wiki|Hindi}} or [[Tibetan]]. Also, he had no [[money]], having refused the {{Wiki|donations}} of his friends; instead, he made several fishmonger and butcher friends pledge to give up their professions forever and become [[vegetarian]], claiming that the good [[karma]] would ensure his [[success]].<ref>Berry 1989, p. 14</ref> [[Success]] appeared far from guaranteed, but arriving in [[India]] with very little [[money]], he somehow entered the good graces of [[Sarat Chandra Das]], an [[Indian]] {{Wiki|British}} agent and [[Tibetan]] [[scholar]], and was given passage to {{Wiki|northern India}}. Kawaguchi would later be accused of spying for Das, but there is no {{Wiki|evidence}} for this, and a close reading of his diary makes it seem quite unlikely.<ref>Hopkirk, Peter (1997): ''Trespassers on the Roof of the [[World]]: The Secret Exploration of [[Tibet]]'', pp. 150-151; 157. Kodansha {{Wiki|Globe}} (Pbk). ISBN 978-1-56836-050-8.</ref> Kawaguchi stayed in [[Darjeeling]] for several months living with a [[Tibetan]] family by Das' arrangement. He became fluent in the [[Tibetan language]], which was at that [[time]] neither systematically taught to foreigners nor compiled, by talking to children and women on the street.<ref>Berry 1989, p. 26-7</ref> | + | He left [[Japan]] for [[India]] in June, 1897, without a guide or map, simply buying his way onto a cargo boat. He had a smattering of English but did not know a [[word]] of {{Wiki|Hindi}} or [[Tibetan]]. Also, he had no [[money]], having refused the {{Wiki|donations}} of his friends; instead, he made several fishmonger and butcher friends pledge to give up their professions forever and become [[vegetarian]], claiming that the good [[karma]] would ensure his [[success]].<ref>Berry 1989, p. 14</ref> [[Success]] appeared far from guaranteed, but arriving in [[India]] with very little [[money]], he somehow entered the good graces of [[Sarat Chandra Das]], an [[Indian]] {{Wiki|British}} agent and [[Tibetan]] [[scholar]], and was given passage to {{Wiki|northern India}}. [[Kawaguchi]] would later be accused of spying for Das, but there is no {{Wiki|evidence}} for this, and a close reading of his diary makes it seem quite unlikely.<ref>Hopkirk, Peter (1997): ''Trespassers on the Roof of the [[World]]: The Secret Exploration of [[Tibet]]'', pp. 150-151; 157. Kodansha {{Wiki|Globe}} (Pbk). ISBN 978-1-56836-050-8.</ref> [[Kawaguchi]] stayed in [[Darjeeling]] for several months living with a [[Tibetan]] family by Das' arrangement. He became fluent in the [[Tibetan language]], which was at that [[time]] neither systematically taught to foreigners nor compiled, by talking to children and women on the street.<ref>Berry 1989, p. 26-7</ref> |

| − | Crossing over the [[Himalayas]] on an unpatrolled dirt road with an untrustworthy guide, Kawaguchi soon found himself alone and lost on the [[Tibetan]] plateau. He had the good [[fortune]] to befriend every {{Wiki|wanderer}} he met in the countryside, including [[monks]], shepherds, and even bandits, but he still took almost four years to reach [[Lhasa]] after stopovers at a number of [[monasteries]] and a [[pilgrimage]] round [[sacred]] [[Mount Kailash]] in {{Wiki|western}} [[Tibet]]. He posed as a {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[monk]] and gained a reputation as an {{Wiki|excellent}} doctor which led to him having an audience with the 13th [[Dalai Lama]], [[Thubten Gyatso]] (1876 to 1933).<ref>Kawaguchi, Ekai (1909): ''Three Years in [[Tibet]]'', pp. 309-322. Reprint: [[Book]] [[Faith]] [[India]] (1995), {{Wiki|Delhi}}. ISBN 81-7303-036-7</ref> He spent some [[time]] living in [[Sera Monastery]].<ref>Kawaguchi, Ekai (1909): ''Three Years in [[Tibet]]'', pp. 323-328. Reprint: [[Book]] [[Faith]] [[India]] (1995), {{Wiki|Delhi}}. ISBN 81-7303-036-7</ref> | + | Crossing over the [[Himalayas]] on an unpatrolled dirt road with an untrustworthy guide, [[Kawaguchi]] soon found himself alone and lost on the [[Tibetan]] plateau. He had the good [[fortune]] to befriend every {{Wiki|wanderer}} he met in the countryside, including [[monks]], shepherds, and even bandits, but he still took almost four years to reach [[Lhasa]] after stopovers at a number of [[monasteries]] and a [[pilgrimage]] round [[sacred]] [[Mount Kailash]] in {{Wiki|western}} [[Tibet]]. He posed as a {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[monk]] and gained a reputation as an {{Wiki|excellent}} doctor which led to him having an audience with the 13th [[Dalai Lama]], [[Thubten Gyatso]] (1876 to 1933).<ref>[[Kawaguchi]], Ekai (1909): ''Three Years in [[Tibet]]'', pp. 309-322. Reprint: [[Book]] [[Faith]] [[India]] (1995), {{Wiki|Delhi}}. ISBN 81-7303-036-7</ref> He spent some [[time]] living in [[Sera Monastery]].<ref>[[Kawaguchi]], Ekai (1909): ''Three Years in [[Tibet]]'', pp. 323-328. Reprint: [[Book]] [[Faith]] [[India]] (1995), {{Wiki|Delhi}}. ISBN 81-7303-036-7</ref> |

| − | While Kawaguchi was in [[Lhasa]], 34 year old Narita Yasuteru, who was a spy for the [[Japanese]] [[Intelligence]], visited the city for about a fortnight. Little else is known about this man or what [[information]] he took back to [[Japan]].<ref>Hyer, Paul (1979). "Narita Yasuteru: First [[Japanese]] to Enter [[Tibet]]". ''[[Tibet]] Journal'' Vol. IV, No. 3, Autumn 1979, pp. 12-19.</ref><ref>See also [http://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=ja&u=http://www.jacar.go.jp/english/nichiro/keyword01.htm&sa=X&oi=translate&resnum=1&ct=result&prev=/search%3Fq%3D%2522Narita%2BYasuteru%2522%26hl%3Den%26sa%3DG]</ref> While Kawaguchi and Narita never encountered each other, Narita would later anonymously accuse Kawaguchi of having never been to [[Tibet]]; this accusation was quickly debunked by the [[Japanese]] newspapers.<ref>Berry 1989, pp. 250-251</ref> | + | While [[Kawaguchi]] was in [[Lhasa]], 34 year old Narita Yasuteru, who was a spy for the [[Japanese]] [[Intelligence]], visited the city for about a fortnight. Little else is known about this man or what [[information]] he took back to [[Japan]].<ref>Hyer, Paul (1979). "Narita Yasuteru: First [[Japanese]] to Enter [[Tibet]]". ''[[Tibet]] Journal'' Vol. IV, No. 3, Autumn 1979, pp. 12-19.</ref><ref>See also [http://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=ja&u=http://www.jacar.go.jp/english/nichiro/keyword01.htm&sa=X&oi=translate&resnum=1&ct=result&prev=/search%3Fq%3D%2522Narita%2BYasuteru%2522%26hl%3Den%26sa%3DG]</ref> While [[Kawaguchi]] and Narita never encountered each other, Narita would later anonymously accuse [[Kawaguchi]] of having never been to [[Tibet]]; this accusation was quickly debunked by the [[Japanese]] newspapers.<ref>Berry 1989, pp. 250-251</ref> |

| − | Kawaguchi seems to have expected [[Tibet]] to have been quite different from the real country he encountered, constantly putting it in critical contrast to [[Japan]]. His travelogue shows his shock at the lack of [[hygiene]] amongst [[Tibetans]], the filth of [[Tibetan]] cities, and by many [[Tibetan]] customs, including {{Wiki|sexual}} practices, [[monastic]] immoderation, corruption and superstitious [[beliefs]]. On the other hand, he had great admiration for many [[Tibetans]] ranging from great [[religious]] and {{Wiki|political}} leaders to common [[people]] and made many friends while he was in [[Tibet]].<ref>Berry (2005), pp. 37-45, 57.</ref> | + | [[Kawaguchi]] seems to have expected [[Tibet]] to have been quite different from the real country he encountered, constantly putting it in critical contrast to [[Japan]]. His travelogue shows his shock at the lack of [[hygiene]] amongst [[Tibetans]], the filth of [[Tibetan]] cities, and by many [[Tibetan]] customs, including {{Wiki|sexual}} practices, [[monastic]] immoderation, corruption and superstitious [[beliefs]]. On the other hand, he had great admiration for many [[Tibetans]] ranging from great [[religious]] and {{Wiki|political}} leaders to common [[people]] and made many friends while he was in [[Tibet]].<ref>Berry (2005), pp. 37-45, 57.</ref> |

| − | Kawaguchi devoted his entire [[time]] in [[Tibet]] to [[Buddhist pilgrimage]] and study. Although he mastered the difficult {{Wiki|terminology}} of the classical [[Tibetan language]] and was able to pass for a [[Tibetan]], he was surprisingly intolerant of [[Tibetans]]' minor violations of [[monastic]] laws, and of the eating of meat in a country with very little arable farmland. As a result he did not fit in well in [[monastic]] circles, instead finding work as a doctor of {{Wiki|Chinese}} and {{Wiki|Western}} [[medicine]]. His services were soon in high demand.<ref>Berry 1989, pp. 169-200</ref> | + | [[Kawaguchi]] devoted his entire [[time]] in [[Tibet]] to [[Buddhist pilgrimage]] and study. Although he mastered the difficult {{Wiki|terminology}} of the classical [[Tibetan language]] and was able to pass for a [[Tibetan]], he was surprisingly intolerant of [[Tibetans]]' minor violations of [[monastic]] laws, and of the eating of meat in a country with very little arable farmland. As a result he did not fit in well in [[monastic]] circles, instead finding work as a doctor of {{Wiki|Chinese}} and {{Wiki|Western}} [[medicine]]. His services were soon in high demand.<ref>Berry 1989, pp. 169-200</ref> |

{{Tibetan Buddhism}} | {{Tibetan Buddhism}} | ||

| − | Kawaguchi spent his [[time]] in [[Lhasa]] in disguise and, following a tip that his cover had been blown, had to flee the country hurriedly. He almost petitioned the government to let him stay as an honest and apolitical [[monk]], but the intimations of high-ranking friends convinced him not to. Even so, several of the [[people]] who had sheltered him were horribly tortured and mutilated.<ref>Hopkirk, Peter (1997): ''Trespassers on the Roof of the [[World]]: The Secret Exploration of [[Tibet]]'', pp. 149, 154. Kodansha {{Wiki|Globe}} (Pbk). ISBN 978-1-56836-050-8.</ref> Kawaguchi was deeply concerned for his friends, and despite his ill health and lack of funds, after leaving the country he used all his connections to petition the {{Wiki|Nepalese}} Prime Minister [[Chandra Shamsher Jang Bahadur Rana|Chandra Shumsher Rana]] for help. On the Prime Minister's recommendation, the {{Wiki|Tibetan Government}} released Kawaguchi's loyal [[Tibetan]] friends from jail.<ref name="Japanese_Embassy">"The First Recorded [[Japanese]] Visitor: [[Ekai Kawaguchi]]" - pdf file from the [[Japanese]] Embassy in [[Nepal]]. [http://www.np.emb-japan.go.jp/graph/relation/ekai.pdf]</ref> | + | [[Kawaguchi]] spent his [[time]] in [[Lhasa]] in disguise and, following a tip that his cover had been blown, had to flee the country hurriedly. He almost petitioned the government to let him stay as an honest and apolitical [[monk]], but the intimations of high-ranking friends convinced him not to. Even so, several of the [[people]] who had sheltered him were horribly tortured and mutilated.<ref>Hopkirk, Peter (1997): ''Trespassers on the Roof of the [[World]]: The Secret Exploration of [[Tibet]]'', pp. 149, 154. Kodansha {{Wiki|Globe}} (Pbk). ISBN 978-1-56836-050-8.</ref> [[Kawaguchi]] was deeply concerned for his friends, and despite his ill health and lack of funds, after leaving the country he used all his connections to petition the {{Wiki|Nepalese}} Prime Minister [[Chandra Shamsher Jang Bahadur Rana|Chandra Shumsher Rana]] for help. On the Prime Minister's recommendation, the {{Wiki|Tibetan Government}} released [[Kawaguchi's]] loyal [[Tibetan]] friends from jail.<ref name="Japanese_Embassy">"The First Recorded [[Japanese]] Visitor: [[Ekai Kawaguchi]]" - pdf file from the [[Japanese]] Embassy in [[Nepal]]. [http://www.np.emb-japan.go.jp/graph/relation/ekai.pdf]</ref> |

Partly as a result of hearing about the discovery of an [[Ashoka Pillar]] in 1896 identifying [[Lumbini]] as the birthplace of [[Gautama Buddha]], he visited [[Lumbini]] with other [[Japanese]] [[pilgrims]] in 1912. He then returned to [[Tibet]] a final [[time]] in 1913. While his more mature {{Wiki|narrative}} of this trip is mainly occupied with [[Japanese]] poems about the [[beauty]] of the land, he could not resist some final criticisms of the [[monks]]' lax [[attitude]] towards [[monastic rules]].<ref>Berry 1989, p. 292</ref> He returned to [[Japan]] and became an {{Wiki|independent}} [[monk]], living with his brother's family for the rest of his [[life]], and earning an income from [[scholarly]] publications. He refused to assist the {{Wiki|military}} police when they sought [[intelligence]] on [[Tibet]], and [[died]] in 1945.<ref>Berry 1989, p. 299</ref> | Partly as a result of hearing about the discovery of an [[Ashoka Pillar]] in 1896 identifying [[Lumbini]] as the birthplace of [[Gautama Buddha]], he visited [[Lumbini]] with other [[Japanese]] [[pilgrims]] in 1912. He then returned to [[Tibet]] a final [[time]] in 1913. While his more mature {{Wiki|narrative}} of this trip is mainly occupied with [[Japanese]] poems about the [[beauty]] of the land, he could not resist some final criticisms of the [[monks]]' lax [[attitude]] towards [[monastic rules]].<ref>Berry 1989, p. 292</ref> He returned to [[Japan]] and became an {{Wiki|independent}} [[monk]], living with his brother's family for the rest of his [[life]], and earning an income from [[scholarly]] publications. He refused to assist the {{Wiki|military}} police when they sought [[intelligence]] on [[Tibet]], and [[died]] in 1945.<ref>Berry 1989, p. 299</ref> | ||

| − | He was a [[friend]] of Mrs. [[Annie Besant]], President of the [[Theosophical Society]], who encouraged him to publish the English text of his [[book]], ''Three Years in [[Tibet]]''.<ref>Kawaguchi, Ekai (1909): ''Three Years in [[Tibet]]'', page vii. Reprint: [[Book]] [[Faith]] [[India]] (1995), {{Wiki|Delhi}}. ISBN 81-7303-036-7</ref> The Government of [[Nepal]] issued a postage stamp in 2003 commemorating Kawaguchi's visits to that country. He is also said to have planted two saplings of [[Himalayan]] Cicada [[trees]] (also called: Riang Riang; ''[[Ploiarium alternifolium]]''), which he had brought back with him, near the gate of the Obaku-san Manpukuji [[Zen]] [[Buddhist temple]] on the outskirts of [[Kyoto]], where he had studied as a young man.<ref> These are now grown into tall [[trees]]. From the [[Japanese]] {{Wiki|embassy}} in [[Nepal]] [http://www.np.emb-japan.go.jp/history/ekai.html]</ref> | + | He was a [[friend]] of Mrs. [[Annie Besant]], President of the [[Theosophical Society]], who encouraged him to publish the English text of his [[book]], ''Three Years in [[Tibet]]''.<ref>[[Kawaguchi]], Ekai (1909): ''Three Years in [[Tibet]]'', page vii. Reprint: [[Book]] [[Faith]] [[India]] (1995), {{Wiki|Delhi}}. ISBN 81-7303-036-7</ref> The Government of [[Nepal]] issued a postage stamp in 2003 commemorating [[Kawaguchi's]] visits to that country. He is also said to have planted two saplings of [[Himalayan]] Cicada [[trees]] (also called: Riang Riang; ''[[Ploiarium alternifolium]]''), which he had brought back with him, near the gate of the [[Obaku-san Manpukuji]] [[Zen]] [[Buddhist temple]] on the outskirts of [[Kyoto]], where he had studied as a young man.<ref> These are now grown into tall [[trees]]. From the [[Japanese]] {{Wiki|embassy}} in [[Nepal]] [http://www.np.emb-japan.go.jp/history/ekai.html]</ref> |

==Footnotes== | ==Footnotes== | ||

| Line 27: | Line 28: | ||

*Berry, Scott. (2005). ''The Rising {{Wiki|Sun}} in the [[Land of Snows]]: [[Japanese]] Involvement in [[Tibet]] in the Early 20th Century''. Ardash [[Books]], {{Wiki|New Delhi}}. ISBN 81-87138-97-1. | *Berry, Scott. (2005). ''The Rising {{Wiki|Sun}} in the [[Land of Snows]]: [[Japanese]] Involvement in [[Tibet]] in the Early 20th Century''. Ardash [[Books]], {{Wiki|New Delhi}}. ISBN 81-87138-97-1. | ||

* Hopkirk, Peter (1997): ''Trespassers on the Roof of the [[World]]: The Secret Exploration of [[Tibet]].'' Kodansha {{Wiki|Globe}} (Pbk). ISBN 978-1-56836-050-8. | * Hopkirk, Peter (1997): ''Trespassers on the Roof of the [[World]]: The Secret Exploration of [[Tibet]].'' Kodansha {{Wiki|Globe}} (Pbk). ISBN 978-1-56836-050-8. | ||

| − | * Kawaguchi, Ekai (1909): ''Three Years in [[Tibet]]''. Reprint: [[Book]] [[Faith]] [[India]] (1995), {{Wiki|Delhi}}. ISBN 81-7303-036-7./ [http://www.orchidbooks.com/bib_hima.html#thryrstib Orchid Press], [[Thailand]]. (2003) ISBN 974-524-014-1. Originally published by The [[Theosophical]] Office, Adyar, Madras, 1909. | + | * [[Kawaguchi]], Ekai (1909): ''Three Years in [[Tibet]]''. Reprint: [[Book]] [[Faith]] [[India]] (1995), {{Wiki|Delhi}}. ISBN 81-7303-036-7./ [http://www.orchidbooks.com/bib_hima.html#thryrstib Orchid Press], [[Thailand]]. (2003) ISBN 974-524-014-1. Originally published by The [[Theosophical]] Office, Adyar, Madras, 1909. |

| − | *Subedi, [[Abhi]]: Ekai Kawaguchi:The Trespassing Insider. [[Mandala]] [[Book]] Point. [[Kathmandu]], 1999. | + | *Subedi, [[Abhi]]: [[Ekai Kawaguchi]]:The Trespassing Insider. [[Mandala]] [[Book]] Point. [[Kathmandu]], 1999. |

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

{{commonscat}} | {{commonscat}} | ||

*[http://www.pref.kyoto.jp/visitkyoto/en/theme/sites/shrines/temples/obakusan/ Brief description and photo of the Obakusan Manpuku-ji Temple] | *[http://www.pref.kyoto.jp/visitkyoto/en/theme/sites/shrines/temples/obakusan/ Brief description and photo of the Obakusan Manpuku-ji Temple] | ||

Revision as of 01:49, 3 February 2014

{{Nihongo|Ekai Kawaguchi 河口慧海 [[Kawaguchi Ekai}} (February 26, 1866 – February 24, 1945) was a Japanese Buddhist monk, famed for his four journeys to Nepal (in 1899, 1903, 1905 and 1913), and two to Tibet (July 4, 1900–June 15, 1902, 1913–1915), being the first recorded Japanese citizen to travel in either country.[1][2]

From an early age Kawaguchi, whose birth name was Sadajiro, was passionate about becoming a monk. In fact, his passion was unusual in a country that was quickly modernizing; he gave serious attention to the monastic vows of vegetarianism, chastity, and temperance even as other monks were happily abandoning them. As a result he became disgusted with the worldliness and political corruption of the Japanese Buddhist world.[3] Until March, 1891, he worked as the Rector of the Zen Gohyaku rakan Monastery (五百羅漢寺 Gohyaku-rakan-ji) in Tokyo (a large temple which contains 500 rakan icons). He then spent about 3 years as a hermit in Kyoto studying Chinese Buddhist texts and learning Pali, to no use; he ran into political squabbles even as a hermit. Finding Japanese Buddhism too corrupt, he decided to go to Tibet instead, despite the fact that the country was officially off limits to all foreigners.

He left Japan for India in June, 1897, without a guide or map, simply buying his way onto a cargo boat. He had a smattering of English but did not know a word of Hindi or Tibetan. Also, he had no money, having refused the donations of his friends; instead, he made several fishmonger and butcher friends pledge to give up their professions forever and become vegetarian, claiming that the good karma would ensure his success.[4] Success appeared far from guaranteed, but arriving in India with very little money, he somehow entered the good graces of Sarat Chandra Das, an Indian British agent and Tibetan scholar, and was given passage to northern India. Kawaguchi would later be accused of spying for Das, but there is no evidence for this, and a close reading of his diary makes it seem quite unlikely.[5] Kawaguchi stayed in Darjeeling for several months living with a Tibetan family by Das' arrangement. He became fluent in the Tibetan language, which was at that time neither systematically taught to foreigners nor compiled, by talking to children and women on the street.[6]

Crossing over the Himalayas on an unpatrolled dirt road with an untrustworthy guide, Kawaguchi soon found himself alone and lost on the Tibetan plateau. He had the good fortune to befriend every wanderer he met in the countryside, including monks, shepherds, and even bandits, but he still took almost four years to reach Lhasa after stopovers at a number of monasteries and a pilgrimage round sacred Mount Kailash in western Tibet. He posed as a Chinese monk and gained a reputation as an excellent doctor which led to him having an audience with the 13th Dalai Lama, Thubten Gyatso (1876 to 1933).[7] He spent some time living in Sera Monastery.[8]

While Kawaguchi was in Lhasa, 34 year old Narita Yasuteru, who was a spy for the Japanese Intelligence, visited the city for about a fortnight. Little else is known about this man or what information he took back to Japan.[9][10] While Kawaguchi and Narita never encountered each other, Narita would later anonymously accuse Kawaguchi of having never been to Tibet; this accusation was quickly debunked by the Japanese newspapers.[11]

Kawaguchi seems to have expected Tibet to have been quite different from the real country he encountered, constantly putting it in critical contrast to Japan. His travelogue shows his shock at the lack of hygiene amongst Tibetans, the filth of Tibetan cities, and by many Tibetan customs, including sexual practices, monastic immoderation, corruption and superstitious beliefs. On the other hand, he had great admiration for many Tibetans ranging from great religious and political leaders to common people and made many friends while he was in Tibet.[12]

Kawaguchi devoted his entire time in Tibet to Buddhist pilgrimage and study. Although he mastered the difficult terminology of the classical Tibetan language and was able to pass for a Tibetan, he was surprisingly intolerant of Tibetans' minor violations of monastic laws, and of the eating of meat in a country with very little arable farmland. As a result he did not fit in well in monastic circles, instead finding work as a doctor of Chinese and Western medicine. His services were soon in high demand.[13]

Template:Tibetan Buddhism Kawaguchi spent his time in Lhasa in disguise and, following a tip that his cover had been blown, had to flee the country hurriedly. He almost petitioned the government to let him stay as an honest and apolitical monk, but the intimations of high-ranking friends convinced him not to. Even so, several of the people who had sheltered him were horribly tortured and mutilated.[14] Kawaguchi was deeply concerned for his friends, and despite his ill health and lack of funds, after leaving the country he used all his connections to petition the Nepalese Prime Minister Chandra Shumsher Rana for help. On the Prime Minister's recommendation, the Tibetan Government released Kawaguchi's loyal Tibetan friends from jail.[1]

Partly as a result of hearing about the discovery of an Ashoka Pillar in 1896 identifying Lumbini as the birthplace of Gautama Buddha, he visited Lumbini with other Japanese pilgrims in 1912. He then returned to Tibet a final time in 1913. While his more mature narrative of this trip is mainly occupied with Japanese poems about the beauty of the land, he could not resist some final criticisms of the monks' lax attitude towards monastic rules.[15] He returned to Japan and became an independent monk, living with his brother's family for the rest of his life, and earning an income from scholarly publications. He refused to assist the military police when they sought intelligence on Tibet, and died in 1945.[16]

He was a friend of Mrs. Annie Besant, President of the Theosophical Society, who encouraged him to publish the English text of his book, Three Years in Tibet.[17] The Government of Nepal issued a postage stamp in 2003 commemorating Kawaguchi's visits to that country. He is also said to have planted two saplings of Himalayan Cicada trees (also called: Riang Riang; Ploiarium alternifolium), which he had brought back with him, near the gate of the Obaku-san Manpukuji Zen Buddhist temple on the outskirts of Kyoto, where he had studied as a young man.[18]

Footnotes

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "The First Recorded Japanese Visitor: Ekai Kawaguchi" - pdf file from the Japanese Embassy in Nepal. [1]

- ↑ Hyer, Paul (1979). "Narita Yasuteru: First Japanese to Enter Tibet". Tibet Journal Vol. IV, No. 2, Autumn 1979, p. 12.

- ↑ Berry 1989, p. 11-12

- ↑ Berry 1989, p. 14

- ↑ Hopkirk, Peter (1997): Trespassers on the Roof of the World: The Secret Exploration of Tibet, pp. 150-151; 157. Kodansha Globe (Pbk). ISBN 978-1-56836-050-8.

- ↑ Berry 1989, p. 26-7

- ↑ Kawaguchi, Ekai (1909): Three Years in Tibet, pp. 309-322. Reprint: Book Faith India (1995), Delhi. ISBN 81-7303-036-7

- ↑ Kawaguchi, Ekai (1909): Three Years in Tibet, pp. 323-328. Reprint: Book Faith India (1995), Delhi. ISBN 81-7303-036-7

- ↑ Hyer, Paul (1979). "Narita Yasuteru: First Japanese to Enter Tibet". Tibet Journal Vol. IV, No. 3, Autumn 1979, pp. 12-19.

- ↑ See also [2]

- ↑ Berry 1989, pp. 250-251

- ↑ Berry (2005), pp. 37-45, 57.

- ↑ Berry 1989, pp. 169-200

- ↑ Hopkirk, Peter (1997): Trespassers on the Roof of the World: The Secret Exploration of Tibet, pp. 149, 154. Kodansha Globe (Pbk). ISBN 978-1-56836-050-8.

- ↑ Berry 1989, p. 292

- ↑ Berry 1989, p. 299

- ↑ Kawaguchi, Ekai (1909): Three Years in Tibet, page vii. Reprint: Book Faith India (1995), Delhi. ISBN 81-7303-036-7

- ↑ These are now grown into tall trees. From the Japanese embassy in Nepal [3]

References

- Berry, Scott: A Stranger in Tibet: The Adventures of a Wandering Zen Monk. Kodansha International, Tokyo, 1989. Also published as A Stranger in Tibet: Adventures of a Zen Monk by HarperCollins (1990) ISBN 978-0-00-215337-9.

- Berry, Scott. (2005). The Rising Sun in the Land of Snows: Japanese Involvement in Tibet in the Early 20th Century. Ardash Books, New Delhi. ISBN 81-87138-97-1.

- Hopkirk, Peter (1997): Trespassers on the Roof of the World: The Secret Exploration of Tibet. Kodansha Globe (Pbk). ISBN 978-1-56836-050-8.

- Kawaguchi, Ekai (1909): Three Years in Tibet. Reprint: Book Faith India (1995), Delhi. ISBN 81-7303-036-7./ Orchid Press, Thailand. (2003) ISBN 974-524-014-1. Originally published by The Theosophical Office, Adyar, Madras, 1909.

- Subedi, Abhi: Ekai Kawaguchi:The Trespassing Insider. Mandala Book Point. Kathmandu, 1999.