Difference between revisions of "Characteristics of indigenous Tibetan culture"

| Line 155: | Line 155: | ||

Ekvall’s {{Wiki|novel}} is based on his study of pastoral [[nomadic]] [[Tibetan]] [[life]] in the 1950s. In it he describes the dangers of setting up of a new tent and household hearth. | Ekvall’s {{Wiki|novel}} is based on his study of pastoral [[nomadic]] [[Tibetan]] [[life]] in the 1950s. In it he describes the dangers of setting up of a new tent and household hearth. | ||

| − | [7] The | + | [7] The General [[Sadhana]] Format for [[Meditational Deity]] Generation, 9-10, a [[Nyingma]] practice text in the possession of the author, compiled from the [[Nam Chö]] (Sky [[Dharma]]) cycle of the [[Tertön]] [[Migyur Dorje]], under the [[direction]] of [[His Holiness]] The Third Drubwang [[Pedma Norbu]] |

[[Rinpoché]], distributed through [[Mirror Wisdom]] Publications, Greenbrae, Calif. | [[Rinpoché]], distributed through [[Mirror Wisdom]] Publications, Greenbrae, Calif. | ||

Latest revision as of 16:41, 20 March 2014

The World of the Spirits: World as Being

In general shamanism expresses a philosophy of life that holds all beings— human, animal, or plant—to be qualitatively equivalent: all phenomena of nature, including human beings, plants, animals, rocks, rain, thunder, lightening, stars and planets, and even tools, are

animate, imbued with a life essence or soul or, in the case of human beings, more than one soul. . . . The origin of life is held to lie in transformation. . . [1]

§ Such a world-view constitutes what Peter Furst calls an “ecological belief system.” It is overwhelmingly apparent in Tibetan culture, where the land itself is identified with the spirit of a great demoness conquered and subjugated by the Buddhist religion.[2]

The great temple of Jokhang in Lhasa stands over her heart; others pin her hips, shoulders, elbows, feet, and hands.[3]

§ The most prominent feature of ordinary Tibetan religious life is the belief in various types and classes of gods or lha. The Tibetan word is a broad and inclusive one: in popular terminology, it refers not only to the heaven-dwelling gods of the Buddhist cosmology, but equally to the local gods of a particular place, the gods associated with nature, the ghosts of certain people, as well as the meditational divinities who form the focus of Buddhist tantric practice—in other words, the entire world of spirits, worldly or

enlightened. There are numerous classifications of these spirits

According to one analysis that uses the triune division of the cosmos common throughout the cultures of Central Asia, there are three classes of spirits related to the three cosmic zones:

(1) sky or heaven where the lha (benevolent gods) dwell;

(2) the earth and

its atmosphere where the aggressive nyen and tsen deities predominate on mountain tops and in rocks, as well as the capricious sa-dag, the ‘earth-lords’ or ‘soil-owners’; and

(3) the subterranean worlds beneath the earth and in the depths of lakes and rivers where the

dangerous water-serpent spirits, the lu, live. There is a great deal of overlap and confusion with regard to such classifications The Lu—spirits of lakes and rivers.

Popular religious activity is primarily defensive and centred around propitiating those spirits who are both powerful and unreliable in their dealings with humans. Among the most prominent of those that are believed to cause trouble are the lu, a class of water spirits who appear as snakes and that correspond to the nāgas of Indian mythology. Their presence can create anxiety among Tibetans with regard to activities that disturb their dwelling places, such as fishing, boating, or rafting timber;[4] they are believed to send

leprosy when angered. Roaming the earth, are the nyen associated with trees and who are said to linger around the mountains and valleys. They are believed responsible for sending the sickness of plague and certain types of cancer when they are disturbed. Related to

them are the tsen, the spirits of monks who broke their vows, and the gyalpo, the spirits of evil kings and high lamas. They inhabit rocks and mountains and, having been converted and dominated by Buddhism, are propitiated as protectors of temples, monasteries, and

households.[5]

In old Tibet, the most prevalent of the spirits to be propitiated were the class of the sadak, ‘masters of the earth’, ‘lords of the soil’, who are disturbed especially by activities of building or digging, or polluting the hearth through the careless boiling over

of a pot.

Because of their displeasure, children die or are born dead. Their spiteful blows bring blindness, strange swellings, and the swift rotting of anthrax, the “earth poison”.[6]

It was accepted that from the primordial time of Tibet’s first inhabitants, enmity has been created between humans and the lords of the earth. Spiritually meritorious Buddhist acts of constructing stūpas or temples were thought to be no less immune to the anger of

the sadak than secular activities of house building or drawing water. Hence, Tibetan Buddhist rituals, even those not specifically related to exorcism or protection from evil, commonly begin with the propitiation and domination of the local deities in words such as the

following:

This torma offering cake], within a precious jeweled container,

Instantly becomes amrita nectar: OM AH HUNG

Suddenly the spirits of the place assemble

As a gathering of local spirits, spirits of the land and harmful spirits.

Gather here and partake of this offering torma

So that I may accomplish the Secret Mantra in this place,

Do not act malicious or jealous.

Befriend those beings of virtue and establish conducive conditions.

All negative entities and classes of obstructors, go elsewhere.

If perhaps you do not listen and intend to cause harm,

You will be destroyed by the radiation of Wrathful Wisdom Beings.

Therefore, listen to this command.[7]

§ Every step of practical or religious life could potentially anger the local deities and bring about misfortune or illness. Control of the spirits, a shamanic concern, became a Buddhist concern. To control and subdue the spirits was to establish a reality in

which the Dharma was preeminent.

Communication with the Spirits: Ritual Specialists

§ Intrinsically linked to the world of the spirits are those people who through knowledge of ritual or special endowment are capable of communicating with the spirits on behalf of their community. The purpose of ritual specialists in this world-view is both

reactive and pro-active: reactive in that their task is to discern who among these spirits had been angered and to carry out the required recompense, and pro-active in that they are required to make offerings to the spirits in order to ensure harmony and protection.

§ in the Tibetan tradition, one of the most popular ways of deflecting the attacks of malevolent spirits was through making offerings, especially ransom-offerings.

In this exchange ritual, the spirit is not merely offered a ransom but actively trapped and thrown away in a ritual device constructed of sticks across which coloured wool is stretched in a criss-cross manner. Such rituals of protection and exorcism were classified

in Tibet under the heading of the ‘religion of the gods’ or the ‘customs/conventions related to the gods’ (lha-chos). They were carried out by various kinds of priests, especially those called bön (‘invoker’) and shen (‘sacrificer’).[8] Of these early ritual

specialists there is little record. The earliest evidence from the Dunhuang texts indicate that the bön and the shen were different kinds of ritual experts officiating at the animal sacrifice funeral rituals of the early kings.[9] A Chinese ambassador to the Tibetan

court in 821 C.E. writes that at the palace entrance “priests with feathered headdresses and girdles of tiger-skin beat drums.”[10]

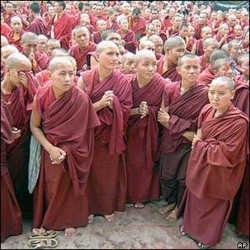

§ Within contemporary Tibetan Buddhist tradition, the function and description of the sung-ma (the protector deities, ‘guardians of the faith’, as well as the oracle priests who embody them) reveals their connection with pre-Buddhist shamanic rituals of possession

and divination. Like other shamans, the sung-ma is identified by behaviour that resembles an insane or possessed person. The Tibetan practice is similar in principle; the sung-ma starts out acting in a bizarre manner and is tested, sometimes by means of divination in

the form of barley dough pellets containing various questions. If he reaches for the right pellet, then he is bound with a scarf and further questioned. If the answers are satisfactory, he is then declared to be the new seat of the protector deity. If he reaches for

the wrong pellet, he dismissed as simply mad.[11]

Other types of pre-Buddhist religious specialists identified by Tibetan historians were the storytellers who recited the legendary myths of origins and heroic exploits, and the singers who entertained the people with sayings, riddles, and the genealogies of clans

and kingdoms. These singers and storytellers represented what was called the ‘religion of men’ or the ‘customs/conventions of men’ (mi-chos).

Along with the priests whose rituals were necessary for dealing with spirits, the story-tellers and singers are said to have ‘protected the kingdom’ through their religious function of relating sacred history, the origins of social institutions, and the wisdom of

the elders.[12] Buddhism in Tibet eventually replaced the old religion as the ‘religion of the gods’ and in many ways it also assimilated the functions related to sacred history, cosmogony and genealogy that constituted the ‘religion of men’.

Gods Inside (la) and Gods Outside (lha)

Concomitant with the ancient Tibetan belief in a plurality of gods or spirits inhabiting and enlivening the world around them was the understanding of the human person as the dwelling place of spirits or souls that enlivened the body. The popular conception of ‘soul

’ in Tibet is captured in the word ‘la’. La can be thought of as the essence of a thing, that which is its inherent strength, power, and vitality. The la has left the body when someone falls unconscious or is extremely ill or suffers a severe fright. The la “has a

definite shape” and is “a mobile soul, which can take its residence anywhere, in a tree, a rock, an animal, but nevertheless remains linked most closely with the life of the person concerned.”[13] The la can fall into the clutches of a demon or a god of some kind, in

which case a complicated ceremony to recover it is carried out, whereby the god or demon is invited to accept in place of the soul a white lamb, and the soul itself is offered the right thigh-bone of a sheep for its support until it returns to its rightful place.[14]

The intermediate, unsupported time when the la has been released by the demon and has not yet arrived at its dwelling place in the body is considered fraught with danger. The soul at this juncture is told, “not to go astray … not to stumble, not to disintegrate …

not to break apart … not to wander about.”[15] The soul, therefore, is not only materially conceived but always requires a support. During Tibetan divination rites when the celebrant is ‘possessed’ by a deity, he holds hidden under his knee a white stone called the ‘

soul-stone’ where the la can reside safely while his body is inhabited by the god.[16] Most commonly, the support or ‘seat’ of the soul is the body, but at the same time, the soul is also thought to reside in external objects such as trees, mountains, lakes, and

stones. One old Tibetan custom is to plant a tree at the birth of a child; that tree then becomes the la-shing, the soul-tree of the child.

La is also a collective concept: the soul of a group, a community, or a particular region is understood to have its support in some feature of the environment. The Sherpas of Nepal look to the fullness and purity of a lake called Womi Ts’o as a sign of their own

community’s strength.[17]

[[

In the Tibetan epic of Gesar of Ling, the Hor people have their life force in a piece of iron or a white stone, but they also have a soul-tree (la-shing) and a soul-fish (la-nya). For an enemy to defeat them, all these seats would have to be destroyed. The seat of

the soul is, of course, kept secret and the hero of the legend defeats the demon, or conversely, is damaged when the secret hiding place of the la is discovered.[18]

Regarding this complex variety of soul concepts, rather than thinking in terms of different souls, life soul, breath soul, and dreaming soul), it might be more helpful in understanding a shamanic world-view to think in terms of various manifestations of the

dimensions of being that constitute a person. In a sense the souls are ‘persons’ or ‘beings’ who act in different ways and fulfill different functions with regard to a variety of states or conditions: waking, sleeping, in death, or in reincarnation. In the same way

that physical and mental aspects of a person are definable yet completely interrelated, so the separate spirit energies of a person have their own characteristics, their own persona, yet cannot be entirely separated one from the other.

As explained above, in the popular Tibetan world-view, the soul is understood to be an integral aspect of the internal dimension of a person as well as an entity that resides externally in various features of the environment. This brings it into close proximation

to the idea of the lha, the indwelling spirit or deity of trees, rocks, rivers, and so forth. Further overlapping of these ideas is to be found in the belief that a person has five or six protective gods (gowé lha) that are ‘born with’, or take up residence in, the

child at birth. Although the lists are various and conflicting, they agree that the gods come to be associated with the child at birth and that they reside in the different parts of the body. The ‘god of life’ (srog-lha) resides in the heart; the ‘man’s god’ (p’o-lha)

responsible for male fortune and descendants, in the right armpit; the ‘woman’s god’ (mo-lha) responsible for female fortune and descendants, in the left armpit; the ‘god who protects against enemies’ (dgra-lha), at the right shoulder; and the ‘god of the country or

locality’ (yul-lha), at the crown of the head.[19] All these gods born with a person are propitiated and requested to protect and keep the person from harm. At the same time, they are themselves identified as internal aspects of the person’s life force or soul, and

similar pronunciation (‘la’ versus ‘lha’) makes them even more conflated.

Among the Tibetans, belief in local nature gods was conjoined with legends of the divine origin of their first king as descended from a mountain and identified with the mountain. In the Tibetan pantheon of spirits, the gods of rocks and mountains are powerful and

feared. Mountain-gods are called tsen, meaning ‘Mighty’, and belong to a category of ‘hero-gods’ that hark back to the beginnings of Tibetan military and political power.

In A Cultural History of Tibet, Snellgrove and Richardson postulate the origins of the Tibetan peoples in pastoral and nomadic non-Chinese tribes of eastern central Asia.[20] Each tribe probably had its own sacred mountain, which was considered to be the seat or

throne of the tribe’s protective deity. The enduring importance and strong feeling in the hearts of Tibetans regarding the overseeing mountain god for a particular group or village is carried into the present day by the words of Thubten Norbu, eldest brother of the

Dalai Lama. In his autobiography, he speaks of Kye, the mountain god of his village who is depicted as a horseman in the temple at the edge of the village:

From our roof you could see far into the fruitful countryside below. It was dominated by the great “house-mountain” Kyeri. The sight of this majestic glacier mountain, which was the throne of our protective deity Kye, always made our hearts beat higher. . . . [21]

And he describes the worship of Kyeri:

The temple which stood surrounded by shady trees on the outskirts of our village was dedicated to Kyeri . . . In the centre was a statue of our protective deity in the guise of a horseman. . . .

Behind the temple was a small eminence on which a stone altar had been erected, and here the inhabitants of Tengster would burn incense in honour of our protective deity and to beg him to grant peace and prosperity to our village. . . .

On a small hill not far from Tengster there was a labtse, that is to say, a heap of stones dedicated to the protective deity of the village. . . . Here you offered up white quartz, coins, turquoises and corals, and prayed for rain, or for sun, or for a good

harvest, or for protection from bad weather.[22]

§ The reverence and worship of the mountain and its presiding deity is echoed in songs from the eighth and ninth centuries, found among the Dunhuang documents, which chronicle the arrival of the first Tibetan king who descended from the sky onto the sacred mountain of Yar-lha-sham-po, the protective mountain of the Yarlung Valley tribe.

According to legend, the descent of the first divine king of Tibet from the sky was by means of what was called the mu rope or mu ladder.[23] This is the Tibetan version of the primordial connecting rope or ladder between earth and heaven that appears in so many

shamanic myths.[24] Although the earliest version of the legends of Tibet’s first king dates to the fourteenth century,[25] the legends reflect a world-view that likely stretches back to the prehistory of the Tibetan region.

King Nyatri Tsenpo, the ‘Neck-Enthroned Mighty One’, is said to have descended from the summit of Mount Yar-lha-sham-po to be greeted by twelve tribal chieftains or sages who acclaimed him as their king and hoisted him onto a palanquin on their necks. In some

versions, the mountain is identified or pictured as a ladder—a tree trunk with seven or nine notches cut into it, each notch representing a level of the heaven worlds.

The Tibetan world-view maintained the tripartite division familiar to several central and inner Asian societies: the gods lha inhabited the upper world, the tsen dominated the middle world, and the lu (serpent deities) ruled the under world. The kings were all

called tsen (Mighty One), establishing their connection with the sacred mountains.

The first king and his six descendants whose tombs were in the sky were known as the ‘Seven Heavenly Thrones’.[26] These first divine kings were said to have their home in the sky where they returned each night. Upon death they returned permanently to their home in

the sky.[27] They did this by means of the mu rope or ‘sky-cord’ that attached to the crown of the head.

A Mongolian source of the same legend reports:

When it was time to transmigrate, they dissolved upwards, starting from the feet, and, by the road of light called Rope-of-Holiness which came out of their head, they left by becoming a rainbow in the sky. Their corpse was thus made an onggon (saint, ancestor and

burial mound) in the country of the gods.[28]

The rope or cord that is the path of the soul to its destination appears in many shamanic cultures. Mortality finally came to the kings of Tibet when the sixth successor after Nyatri Tsenpo, brandishing his sword in battle, accidentally severed his mu rope.

Thereafter the kings were buried in earthly tombs.

The idea of the spirit or soul ascending to the sky by means of a rope of rainbow light from the top of the head found a place in later Tibetan Buddhist rituals called phowa, a ritual whereby consciousness, departing from the body through the crown of the head, is

transferred to a heavenly Buddha paradise. The rainbow path of the early kings can also be recognized in the Tibetan Buddhist belief that certain meditation practices result in the physical body dissolving at death into a body of rainbow light (‘ja’lus). As Tucci

notes, “The connection between heaven and earth is a primeval article of faith for the Tibetan . . .”[29]

[1] Peter T. Furst, “An Overview of Shamanism,” in Ancient Traditions: Shamanism in Central Asia and the Americas, eds. Gary Seaman and Jane S. Day (Niwot, Colo.: University Press of Colorado; Denver: Denver Museum of Natural History, 1994), 2-3.

[2] The earliest historical dating there is for the presence of Buddhism in Tibet is the reign of King Songsten Gampo (ca. 614-650 C.E.). Tradition holds that he built twelve ‘boundary and limb-binding’ Buddhist temples at the four corners of three concentric squares

spreading outwards from Central Tibet, each one acting as a great nail to pin down and subjugate the demoness that represented the untamed land of Tibet. See Janet Gyatso, “Down with the Demoness: Reflections on a Feminine Ground in Tibet,” Tibet Journal 12, no. 4

(1987): 38-53.

[3] In present-day Bhutan, the temples of Kyichu Lhakang in Paro and Jambey Lhakang in Bumthang hold down her left foot and left knee respectively. See Michael Aris, Bhutan: The Early History of a Himalayan Kingdom (Warminster, England: Aris & Phillips Ltd., 1979), 15-

16.

[4] Ekvall, Religious Observances in Tibet, 79.

[5] Samuel, Civilized Shamans, 162-163.

[6] Robert B. Ekvall, Tents Against the Sky (New York: Farrar Straus & Young, 1954), 117.

Ekvall’s novel is based on his study of pastoral nomadic Tibetan life in the 1950s. In it he describes the dangers of setting up of a new tent and household hearth.

[7] The General Sadhana Format for Meditational Deity Generation, 9-10, a Nyingma practice text in the possession of the author, compiled from the Nam Chö (Sky Dharma) cycle of the Tertön Migyur Dorje, under the direction of His Holiness The Third Drubwang Pedma Norbu

Rinpoché, distributed through Mirror Wisdom Publications, Greenbrae, Calif.

[8] Snellgrove and Richardson, A Cultural History of Tibet, 59.

[9] Ibid., 52.

[10] Ibid., 64.

[11] Ibid., 813.

[12] Stein, Tibetan Civilization, 191-193.

[13] Giusseppe Tucci, The Religions of Tibet, trans. Geoffrey Samuel (Bombay: Allied Publishers Private Ltd., 1980), 191-192.

[14] Not only animals or symbolic substitutes are used for ransom: on occasion a human ransom called “substitute in flesh, substitute in bone” can be offered to the demon who would then direct the misfortune towards that person instead. Ibid., 191.

[15] Tucci, The Religions of Tibet, 191.

[16] Ibid., 203, 209.

[17] Samuel, Civilized Shamans, 186.

[18] Stein, Tibetan Civilization, 228.

[19] Samuel, Civilized Shamans,187.

[20] Snellgrove and Richardson, A Cultural History of Tibet, 21.

[21] Norbu as told to Harrer, Tibet is my Country, 24.

[22] Ibid., 52-53.

[23] ‘Mu’ also refers to a class of heavenly spirits and a particular clan of Bon priests.

[24] Eliade, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, 110-112, 428-431.

[25] Snellgrove and Richardson, A Cultural History of Tibet, 23.

[26] George N. Roerich, trans., The Blue Annals, 2d ed. (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1976), 36.

[27] Stein, Tibetan Civilization, 42-43.

[28] Ibid., 225. Stein notes that the manner in which the body dissolves into light beginning with the feet relates to the Tibetan belief that the soul or la circulates monthly through the body in a very specific manner from feet to crown: on the thirtieth and first of

the month, it resides in the sole of the foot (left for men and right for women), and on successive days it rises higher and higher with the waxing moon to arrive at the crown of the head on the fifteenth, the full moon day. Similarly, in the Tibetan Buddhist practice

of visualizing (generating) oneself as the deity, at the time of dissolving the visualization into light, the dissolution takes place from the feet up to the crown.

[29] Tucci, The Religions of Tibet, 246.