Difference between revisions of "Guru Chowang"

(Created page with "thumb|250px| Chokyi Wangchuk (chos kyi dbang phyug), popularly known as Guru Chowang (gu ru chos dbang), was born in Lhodrak (lho brag)...") |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

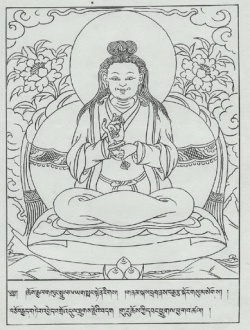

[[File:Guru_chowang_shechen_57.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Guru_chowang_shechen_57.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Chokyi Wangchuk (chos kyi dbang phyug), popularly known as Guru Chowang (gu ru chos dbang), was born in Lhodrak (lho brag), the son of Pangton Trupai Nyingpo (spang ston grub pa'i snying po) and Karza Gonkyi (dkar gza' mgon skyid). His name, which means "lord of doctrine", is said to have been given to him because, when his mother went into labor, his father was in the midst of making a copy of the Mañjuśrīnamasangiti, and at the moment of his birth his father had just written the phrase "lord of doctrine." | + | [[Chokyi Wangchuk]] ([[chos kyi dbang phyug]]), popularly known as [[Guru Chowang]] ([[gu ru chos dbang]]), was born in [[Lhodrak]] ([[lho brag]]), the son of Pangton Trupai [[Nyingpo]] (spang ston grub pa'i [[snying po]]) and Karza Gonkyi (dkar gza' mgon skyid). His [[name]], which means "lord of [[doctrine]]", is said to have been given to him because, when his mother went into labor, his father was in the midst of making a copy of the Mañjuśrīnamasangiti, and at the [[moment]] of his [[birth]] his father had just written the [[phrase]] "lord of [[doctrine]]." |

| − | His father taught him reading and writing when he was four, and by the age of ten he was studying astrology and medicine as well as the tantric cycles Vajrakīla and Vajrapāṇi; at eleven he trained in the Māyājāla, and at thirteen in New Translation school tantric cycles such as Yangdak Heruka, Yamāntaka, and Hayagriva. His father also taught him Dzogchen, Mahāmudrā, Chod, Zhije, the Naro Chodruk (na ro chos drug) of Naropa, and other traditions. | + | His father [[taught]] him reading and [[writing]] when he was four, and by the age of ten he was studying [[astrology]] and [[medicine]] as well as the [[tantric]] cycles [[Vajrakīla]] and [[Vajrapāṇi]]; at eleven he trained in the [[Māyājāla]], and at thirteen in [[New Translation]] school [[tantric]] cycles such as [[Yangdak Heruka]], [[Yamāntaka]], and [[Hayagriva]]. His father also [[taught]] him [[Dzogchen]], [[Mahāmudrā]], [[Chod]], [[Zhije]], the [[Naro Chodruk]] ([[na ro chos drug]]) of [[Naropa]], and other [[traditions]]. |

| − | When Chokyi Wangchuk was seventeen he met the Ngadak Drogon (mnga' bdag 'gro mgon), the son and successor of Nyangrel Nyima Ozer (nyang ral nyi ma 'od zer), who gave him the transmissions of Nyangrel's treasures. The next year he received bodhisattva vows from Sakya Paṇḍita Kunga Gyeltsen (sa skya pan di ta kun dga' rgyal mtshan, 1182-1251) at Nezhi Gangpo (gnas bzhi sgang po) in Lhodrak. | + | When [[Chokyi Wangchuk]] was seventeen he met the Ngadak Drogon (mnga' [[bdag]] 'gro mgon), the son and successor of [[Nyangrel Nyima Ozer]] ([[nyang ral nyi ma 'od zer]]), who gave him the [[transmissions]] of Nyangrel's [[treasures]]. The next year he received [[bodhisattva vows]] from [[Sakya Paṇḍita]] [[Kunga Gyeltsen]] ([[sa skya pan di ta kun dga' rgyal mtshan]], 1182-1251) at Nezhi Gangpo ([[gnas]] bzhi sgang po) in [[Lhodrak]]. |

| − | Chokyi Wangchuk's career as a treasure revealer is said to have began when he was thirteen, when he came into possession of a treasure inventory (gter ma kha byang) that was said to have been revealed at Samye (bsam yes) by Drapa Ngonshe (grwa pa mngon shes, 1012-1090). The inventory was supposedly so dangerous that several false treasure revealers had almost lost their lives trying to follow it, and many said that just keeping it in ones home was to invite harm. Chokyi Wangchuk's father hid the inventory from him, but when he was twenty-two, with the help of a Chod practitioner, he retrieved the inventory. Discovering a supplementary inventory (yang byang) in the valley of Namkachen (gnam skas can), he followed it to reveal a large trove of treasure texts and objects. | + | Chokyi Wangchuk's career as a [[treasure revealer]] is said to have began when he was thirteen, when he came into possession of a [[treasure]] inventory ([[gter ma]] [[kha byang]]) that was said to have been revealed at [[Samye]] (bsam yes) by [[Drapa Ngonshe]] ([[grwa pa mngon shes]], 1012-1090). The inventory was supposedly so [[dangerous]] that several false [[treasure revealers]] had almost lost their [[lives]] trying to follow it, and many said that just keeping it in ones home was to invite harm. Chokyi Wangchuk's father hid the inventory from him, but when he was twenty-two, with the help of a [[Chod]] [[practitioner]], he retrieved the inventory. Discovering a supplementary inventory ([[yang byang]]) in the valley of Namkachen (gnam skas can), he followed it to reveal a large trove of [[treasure texts]] and [[objects]]. |

| − | Chokyi Wangchuk was an early chronicler of the treasure tradition, and was critical in fashioning standards – loosely adhered to, but widely known – that enabled the practice of treasure revelation to become popularly accepted. Among these was the assertion that complete treasure cycles include three elements: guru yoga, Dzogchen, and Avalokiteśvara (bla rdzogs thugs gsum). Perhaps more importantly, Chokyi Wangchuk was an early apologist for the tradition, willing to assert the existence of "false" treasure in defense of the practice as a whole, even naming names. These elements are evident in advice Chokyi Wangchuk's father gave him when he affirmed the authenticity of his first major revelation. This advice is as follows, as translated by Janet Gyatso in her 1993 article on the treasure tradition, recorded in the Second Pawo, Tsuklak Trengwa's (dpa' bo 02 gtsug lag 'phreng ba, 1504-1566) Scholar's Feast (chos 'byung mkha's pa'i dga' ston): | + | [[Chokyi Wangchuk]] was an early chronicler of the [[treasure tradition]], and was critical in fashioning standards – loosely adhered to, but widely known – that enabled the practice of [[treasure revelation]] to become popularly accepted. Among these was the [[assertion]] that complete [[treasure]] cycles include three [[elements]]: [[guru yoga]], [[Dzogchen]], and [[Avalokiteśvara]] ([[bla rdzogs thugs gsum]]). Perhaps more importantly, [[Chokyi Wangchuk]] was an early [[apologist]] for the [[tradition]], willing to assert the [[existence]] of "false" [[treasure]] in defense of the practice as a whole, even naming names. These [[elements]] are evident in advice Chokyi Wangchuk's father gave him when he [[affirmed]] the authenticity of his first major [[revelation]]. This advice is as follows, as translated by [[Janet Gyatso]] in her 1993 article on the [[treasure tradition]], recorded in the Second [[Pawo]], Tsuklak Trengwa's ([[dpa' bo]] 02 [[gtsug lag 'phreng ba]], 1504-1566) Scholar's Feast ([[chos 'byung]] mkha's pa'i dga' ston): |

| − | "If you would listen to me, then make the basic teachings on the Guru, the Great Perfection, and Avalokiteśvara your highest priority. Until you have made the dharma your highest priority, even a hint about magic, evil spells, catapults, weapons, omens, miracles, and other sorts of crooked crafts should not come out of your mouth! Even if one has much learning, if one does not hold [the dharma] most highly, one winds up a beggar in the end. In general, I in no way would disparage the treasure teachings. In the Buddha's sutras and tantras, the treasures are prophesied. They were the practice of the knowledge-holders of old. But previously many treasure discoverers who had extracted treasures had small minds, did not hold the dharma purely, were concerned only with sustenance and riches, and thus did not help beings much; many have been like that. For example, Gya Zhangtrom (rgya zhang khrom), although he discovered many of the treasures of Nubchen Sanggye Yeshe (gnubs sang rgyas ye shes, 1182-1251), propagated negative mantras and damaged the welfare of beings." | + | "If you would listen to me, then make the basic teachings on the [[Guru]], the [[Great Perfection]], and [[Avalokiteśvara]] your [[highest]] priority. Until you have made the [[dharma]] your [[highest]] priority, even a hint about [[magic]], [[evil]] {{Wiki|spells}}, catapults, [[weapons]], {{Wiki|omens}}, [[miracles]], and other sorts of crooked crafts should not come out of your {{Wiki|mouth}}! Even if one has much {{Wiki|learning}}, if one does not hold [the [[dharma]]] most highly, one [[winds]] up a {{Wiki|beggar}} in the end. In general, I in no way would disparage the [[treasure teachings]]. In the [[Buddha's]] [[sutras]] and [[tantras]], the [[treasures]] are prophesied. They were the practice of the [[knowledge-holders]] of old. But previously many [[treasure]] discoverers who had extracted [[treasures]] had small [[minds]], did not hold the [[dharma]] purely, were concerned only with [[sustenance]] and riches, and thus did not help [[beings]] much; many have been like that. For example, [[Gya]] Zhangtrom ([[rgya zhang khrom]]), although he discovered many of the [[treasures]] of [[Nubchen Sanggye Yeshe]] ([[gnubs]] [[sang rgyas]] [[ye shes]], 1182-1251), propagated negative [[mantras]] and damaged the {{Wiki|welfare}} of [[beings]]." |

[[File:66247_Guru_Chowang.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:66247_Guru_Chowang.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Both the notion of norms for complete revelations and the willingness to admit that some practitioners were inauthentic became common elements in later Tibetan presentations. | + | Both the notion of norms for complete revelations and the willingness to admit that some practitioners were inauthentic became common [[elements]] in later [[Tibetan]] presentations. |

| − | Chokyi Wangchuk was also instrumental in establishing the notion that treasure revelation requires the practice of sexual yoga. He claimed that he could not understand one of his own revelations, the Kabgye Sangwa Yongdzog (bka' brgyad gsang ba yong rdzogs) until after he had opened his yogic central channel via sexual yoga. His consort was Jomo Menmo (jo mo sman mo), an established treasure revealer herself. | + | [[Chokyi Wangchuk]] was also instrumental in establishing the notion that [[treasure revelation]] requires the practice of {{Wiki|sexual}} [[yoga]]. He claimed that he could not understand one of his [[own]] revelations, the [[Kabgye]] [[Sangwa]] Yongdzog ([[bka' brgyad]] [[gsang ba]] yong [[rdzogs]]) until after he had opened his [[yogic]] [[central channel]] via {{Wiki|sexual}} [[yoga]]. His [[consort]] was [[Jomo Menmo]] ([[jo mo sman mo]]), an established [[treasure revealer]] herself. |

| − | He is said to have revealed eighteen troves of earth treasure (sa gter – that is, texts and objects physically concealed in the earth) and one trove of mind treasure (dgong gter – a scripture concealed in his own mind stream in a prior incarnation). Among the most influential are the Lama Sangdu (bla ma gsang 'dus), a sadhana and practice on Padmasambhava that includes the widely used prayer known as the Seven Line Supplication; the Sangdu Lamai Tukdrub (gsang 'dus bla ma'i thugs sgrub); the Kabgye Sangwa Yongdzok (bka' brgyad gsang ba yongs rdzogs), one of the three treasure cycles on the Kabgye, or Eight Commands, central to the Mahāyoga section of Nyingma tantra. The Lama Sangdu cycle is also the core of an extensive sacred dance ceremony performed yearly at most Nyingma monasteries, usually on the anniversary of Padmasambhava , the tenth day of the fifth (or sometimes sixth) month of the lunar calendar, known as the Eight Aspects of Guru Rinpoche (gu ru mtshan brgyad). | + | He is said to have revealed eighteen troves of [[earth treasure]] ([[sa gter]] – that is, texts and [[objects]] {{Wiki|physically}} concealed in the [[earth]]) and one trove of [[mind treasure]] (dgong [[gter]] – a [[scripture]] concealed in his [[own mind]] {{Wiki|stream}} in a prior [[incarnation]]). Among the most influential are the [[Lama Sangdu]] ([[bla ma gsang 'dus]]), a [[sadhana]] and practice on [[Padmasambhava]] that includes the widely used [[prayer]] known as the Seven Line Supplication; the [[Sangdu]] Lamai Tukdrub (gsang 'dus bla ma'i thugs sgrub); the [[Kabgye]] [[Sangwa]] Yongdzok ([[bka' brgyad gsang ba yongs rdzogs]]), one of the three [[treasure]] cycles on the [[Kabgye]], or [[Eight Commands]], central to the [[Mahāyoga]] section of [[Nyingma]] [[tantra]]. The [[Lama Sangdu]] cycle is also the core of an extensive [[sacred dance]] {{Wiki|ceremony}} performed yearly at most [[Nyingma monasteries]], usually on the anniversary of [[Padmasambhava]] , the tenth day of the fifth (or sometimes sixth) month of the {{Wiki|lunar calendar}}, known as the Eight Aspects of [[Guru Rinpoche]] ([[gu ru mtshan brgyad]]). |

| − | Chokyi Wangchuk is credited with the construction of the Samdrub Dewachenpo temple (bsam 'grub bde ba chen po), also known as Layak Guru Lhakang (la yak gu ru lha khang) in at Lhalung Monastery (lha lung dgon pa) in Lhodrag. | + | [[Chokyi Wangchuk]] is credited with the construction of the Samdrub Dewachenpo [[temple]] (bsam 'grub [[bde ba chen po]]), also known as Layak [[Guru]] [[Lhakang]] (la {{Wiki|yak}} gu ru [[lha khang]]) in at [[Lhalung Monastery]] (lha lung [[dgon pa]]) in [[Lhodrag]]. |

| − | Among Chokyi Wangchuk's main disciples were Bharo Tsukdzin (bha ro gtsug 'dzin, d.u.), a Newari Dzogchen master whom Chokyi Wangchuk taught while in the Kathmandu valley; Menlungpa Mikyo Dorje (sman lung pa mi skyod rdo rje, d.u.), who was also a disciple of Nyangrel Nyima Ozer; and Maṇi Rinchen of Katok (kaH thog grub thob maNi rin chen, d.u.). Chokyi Wangchuk encouraged Maṇi Rinchen to renounce his vows and take as his consort Chokyi Wangchuk's own daughter, Kundrolbum (kun grol 'bum), but the later refused. | + | Among Chokyi Wangchuk's main [[disciples]] were Bharo Tsukdzin (bha ro gtsug '[[dzin]], d.u.), a [[Newari]] [[Dzogchen master]] whom [[Chokyi Wangchuk]] [[taught]] while in the [[Kathmandu valley]]; Menlungpa [[Mikyo Dorje]] ([[sman]] lung pa [[mi skyod rdo rje]], d.u.), who was also a [[disciple]] of [[Nyangrel Nyima Ozer]]; and [[Maṇi]] Rinchen of [[Katok]] ([[kaH thog]] [[grub thob]] maNi [[rin chen]], d.u.). [[Chokyi Wangchuk]] encouraged [[Maṇi]] Rinchen to {{Wiki|renounce}} his [[vows]] and take as his [[consort]] Chokyi Wangchuk's [[own]] daughter, Kundrolbum (kun grol 'bum), but the later refused. |

| − | In addition to his daughter Kundrolbum, Chokyi Wangchuk had two sons who carried on his teachings: Pema Wangchen (padma dbang chen, d.u.) and Nyal Nyima Oser (gnyal nyi ma 'od zer, d.u.). | + | In addition to his daughter Kundrolbum, [[Chokyi Wangchuk]] had two sons who carried on his teachings: [[Pema Wangchen]] ([[padma]] [[dbang chen]], d.u.) and Nyal [[Nyima]] Oser ([[gnyal]] [[nyi ma 'od zer]], d.u.). |

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

| − | Dudjom Rinpoche. 2002. The Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism. Gyurme Dorje and Matthew Kapstein, trans. Boston: Wisdom, p. 760 ff. | + | [[Dudjom Rinpoche]]. 2002. [[The Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism]]. [[Gyurme Dorje]] and {{Wiki|Matthew Kapstein}}, trans. Boston: Wisdom, p. 760 ff. |

| − | 'Jam mgon kong sprul blo gros mtha' yas. 1976. Gter ston brgya rtsa. In Rin chen gter mdzod chen mo Paro: Ngodrup and Sherab Drimay, p. 52A.4. ff. | + | '[[Jam mgon kong sprul blo gros mtha' yas]]. 1976. [[Gter ston brgya rtsa]]. In [[Rin chen gter mdzod chen mo]] [[Paro]]: [[Ngodrup]] and [[Sherab Drimay]], p. 52A.4. ff. |

| − | Gyatso, Janet. 1993. “The Logic of legitimation in the Tibetan treasure tradition.” History of Religions 33, no. 2: 97-134. | + | Gyatso, Janet. 1993. “The [[Logic]] of legitimation in the [[Tibetan]] [[treasure tradition]].” History of [[Religions]] 33, no. 2: 97-134. |

| − | Gyatso, Janet. 1994. | + | Gyatso, Janet. 1994. “[[Guru]] Chowang's [[Gter]] 'byung [[chen]] mo: An early survey of the [[treasure tradition]] and its strategies in discussing [[Bon]] [[treasure]].” In Per Kvaern, ed. [[Tibetan Studies]]: Proceedings of the 6th Seminar of the International Association for [[Tibetans]] Studies, pp. 275-287. |

| − | Chos kyi dbang phyug. 1979. Gu ru chos dbang gi rang rnam dang zhal gdams. Paro: Ugyen Tempai Gyeltsen. | + | [[Chos kyi dbang phyug]]. 1979. [[Gu ru chos dbang]] gi rang [[rnam]] dang [[zhal gdams]]. [[Paro]]: Ugyen Tempai [[Gyeltsen]]. |

| − | Bradburn, Leslie 1995. Masters of the Nyingma Lineage. Cazadero: Dharma Publications, p. 136 ff. | + | Bradburn, Leslie 1995. [[Masters]] of the [[Nyingma Lineage]]. Cazadero: [[Dharma Publications]], p. 136 ff. |

| − | Dpa' bo gtsug lag 'phreng ba. 1980 (1564). Chos 'byung mkha's pa'i dga' ston. Delhi: Karmapa chodey gyelwae sungrab partun khang. | + | [[Dpa' bo]] [[gtsug lag 'phreng ba]]. 1980 (1564). [[Chos 'byung]] mkha's pa'i dga' ston. {{Wiki|Delhi}}: [[Karmapa]] chodey gyelwae sungrab partun [[khang]]. |

| − | Karma mi 'gyur dbang rgyal. 1978. Gter bton brgya rtsa'i mtshan sdom gsol 'debs chos rgyal bkra shis stobs rgyal gyi mdzad pa'i 'grel pa lo rgyus gter bton chos 'byung. Darjeeling: Taklung Tsetrul Rinpoche Pema Wangyal, Orgyan Kunsang Chokhor Ling, p. 27.2 ff | + | [[Karma]] mi 'gyur [[dbang]] rgyal. 1978. [[Gter]] bton brgya rtsa'i [[mtshan]] [[sdom]] gsol 'debs [[chos rgyal bkra shis]] [[stobs]] rgyal gyi mdzad pa'i 'grel pa [[lo rgyus]] [[gter]] bton [[chos 'byung]]. {{Wiki|Darjeeling}}: [[Taklung Tsetrul Rinpoche]] [[Pema Wangyal]], [[Orgyan]] [[Kunsang]] Chokhor Ling, p. 27.2 ff |

| − | 'Jam dbyang mkhyen brtse'i dbang po. 1972. Gangs can gyi yul du byon pa'i lo pan rnams kyi mtshan tho rags rim tshigs bcad du bsdebs pa ma ha mandita ta shi la ratna'i gsung. In The collected works (gsung 'bum) of the great 'Jam dbyangs mkhyen brtse'i dbang po, v. 19, pp. 1-476. Gangtok: Gonpo Tseten, p. 103a ff. | + | 'Jam dbyang [[mkhyen]] brtse'i [[dbang po]]. 1972. Gangs can gyi yul du byon pa'i lo pan [[rnams]] kyi [[mtshan tho]] rags rim tshigs bcad du bsdebs pa ma ha mandita ta shi la ratna'i [[gsung]]. In The collected works ([[gsung 'bum]]) of the great 'Jam dbyangs [[mkhyen]] brtse'i [[dbang po]], v. 19, pp. 1-476. [[Gangtok]]: [[Gonpo Tseten]], p. 103a ff. |

Revision as of 13:41, 21 November 2015

Chokyi Wangchuk (chos kyi dbang phyug), popularly known as Guru Chowang (gu ru chos dbang), was born in Lhodrak (lho brag), the son of Pangton Trupai Nyingpo (spang ston grub pa'i snying po) and Karza Gonkyi (dkar gza' mgon skyid). His name, which means "lord of doctrine", is said to have been given to him because, when his mother went into labor, his father was in the midst of making a copy of the Mañjuśrīnamasangiti, and at the moment of his birth his father had just written the phrase "lord of doctrine."

His father taught him reading and writing when he was four, and by the age of ten he was studying astrology and medicine as well as the tantric cycles Vajrakīla and Vajrapāṇi; at eleven he trained in the Māyājāla, and at thirteen in New Translation school tantric cycles such as Yangdak Heruka, Yamāntaka, and Hayagriva. His father also taught him Dzogchen, Mahāmudrā, Chod, Zhije, the Naro Chodruk (na ro chos drug) of Naropa, and other traditions.

When Chokyi Wangchuk was seventeen he met the Ngadak Drogon (mnga' bdag 'gro mgon), the son and successor of Nyangrel Nyima Ozer (nyang ral nyi ma 'od zer), who gave him the transmissions of Nyangrel's treasures. The next year he received bodhisattva vows from Sakya Paṇḍita Kunga Gyeltsen (sa skya pan di ta kun dga' rgyal mtshan, 1182-1251) at Nezhi Gangpo (gnas bzhi sgang po) in Lhodrak.

Chokyi Wangchuk's career as a treasure revealer is said to have began when he was thirteen, when he came into possession of a treasure inventory (gter ma kha byang) that was said to have been revealed at Samye (bsam yes) by Drapa Ngonshe (grwa pa mngon shes, 1012-1090). The inventory was supposedly so dangerous that several false treasure revealers had almost lost their lives trying to follow it, and many said that just keeping it in ones home was to invite harm. Chokyi Wangchuk's father hid the inventory from him, but when he was twenty-two, with the help of a Chod practitioner, he retrieved the inventory. Discovering a supplementary inventory (yang byang) in the valley of Namkachen (gnam skas can), he followed it to reveal a large trove of treasure texts and objects.

Chokyi Wangchuk was an early chronicler of the treasure tradition, and was critical in fashioning standards – loosely adhered to, but widely known – that enabled the practice of treasure revelation to become popularly accepted. Among these was the assertion that complete treasure cycles include three elements: guru yoga, Dzogchen, and Avalokiteśvara (bla rdzogs thugs gsum). Perhaps more importantly, Chokyi Wangchuk was an early apologist for the tradition, willing to assert the existence of "false" treasure in defense of the practice as a whole, even naming names. These elements are evident in advice Chokyi Wangchuk's father gave him when he affirmed the authenticity of his first major revelation. This advice is as follows, as translated by Janet Gyatso in her 1993 article on the treasure tradition, recorded in the Second Pawo, Tsuklak Trengwa's (dpa' bo 02 gtsug lag 'phreng ba, 1504-1566) Scholar's Feast (chos 'byung mkha's pa'i dga' ston):

"If you would listen to me, then make the basic teachings on the Guru, the Great Perfection, and Avalokiteśvara your highest priority. Until you have made the dharma your highest priority, even a hint about magic, evil spells, catapults, weapons, omens, miracles, and other sorts of crooked crafts should not come out of your mouth! Even if one has much learning, if one does not hold [the dharma] most highly, one winds up a beggar in the end. In general, I in no way would disparage the treasure teachings. In the Buddha's sutras and tantras, the treasures are prophesied. They were the practice of the knowledge-holders of old. But previously many treasure discoverers who had extracted treasures had small minds, did not hold the dharma purely, were concerned only with sustenance and riches, and thus did not help beings much; many have been like that. For example, Gya Zhangtrom (rgya zhang khrom), although he discovered many of the treasures of Nubchen Sanggye Yeshe (gnubs sang rgyas ye shes, 1182-1251), propagated negative mantras and damaged the welfare of beings."

Both the notion of norms for complete revelations and the willingness to admit that some practitioners were inauthentic became common elements in later Tibetan presentations.

Chokyi Wangchuk was also instrumental in establishing the notion that treasure revelation requires the practice of sexual yoga. He claimed that he could not understand one of his own revelations, the Kabgye Sangwa Yongdzog (bka' brgyad gsang ba yong rdzogs) until after he had opened his yogic central channel via sexual yoga. His consort was Jomo Menmo (jo mo sman mo), an established treasure revealer herself.

He is said to have revealed eighteen troves of earth treasure (sa gter – that is, texts and objects physically concealed in the earth) and one trove of mind treasure (dgong gter – a scripture concealed in his own mind stream in a prior incarnation). Among the most influential are the Lama Sangdu (bla ma gsang 'dus), a sadhana and practice on Padmasambhava that includes the widely used prayer known as the Seven Line Supplication; the Sangdu Lamai Tukdrub (gsang 'dus bla ma'i thugs sgrub); the Kabgye Sangwa Yongdzok (bka' brgyad gsang ba yongs rdzogs), one of the three treasure cycles on the Kabgye, or Eight Commands, central to the Mahāyoga section of Nyingma tantra. The Lama Sangdu cycle is also the core of an extensive sacred dance ceremony performed yearly at most Nyingma monasteries, usually on the anniversary of Padmasambhava , the tenth day of the fifth (or sometimes sixth) month of the lunar calendar, known as the Eight Aspects of Guru Rinpoche (gu ru mtshan brgyad).

Chokyi Wangchuk is credited with the construction of the Samdrub Dewachenpo temple (bsam 'grub bde ba chen po), also known as Layak Guru Lhakang (la yak gu ru lha khang) in at Lhalung Monastery (lha lung dgon pa) in Lhodrag.

Among Chokyi Wangchuk's main disciples were Bharo Tsukdzin (bha ro gtsug 'dzin, d.u.), a Newari Dzogchen master whom Chokyi Wangchuk taught while in the Kathmandu valley; Menlungpa Mikyo Dorje (sman lung pa mi skyod rdo rje, d.u.), who was also a disciple of Nyangrel Nyima Ozer; and Maṇi Rinchen of Katok (kaH thog grub thob maNi rin chen, d.u.). Chokyi Wangchuk encouraged Maṇi Rinchen to renounce his vows and take as his consort Chokyi Wangchuk's own daughter, Kundrolbum (kun grol 'bum), but the later refused.

In addition to his daughter Kundrolbum, Chokyi Wangchuk had two sons who carried on his teachings: Pema Wangchen (padma dbang chen, d.u.) and Nyal Nyima Oser (gnyal nyi ma 'od zer, d.u.).

Sources

Dudjom Rinpoche. 2002. The Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism. Gyurme Dorje and Matthew Kapstein, trans. Boston: Wisdom, p. 760 ff.

'Jam mgon kong sprul blo gros mtha' yas. 1976. Gter ston brgya rtsa. In Rin chen gter mdzod chen mo Paro: Ngodrup and Sherab Drimay, p. 52A.4. ff.

Gyatso, Janet. 1993. “The Logic of legitimation in the Tibetan treasure tradition.” History of Religions 33, no. 2: 97-134.

Gyatso, Janet. 1994. “Guru Chowang's Gter 'byung chen mo: An early survey of the treasure tradition and its strategies in discussing Bon treasure.” In Per Kvaern, ed. Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the 6th Seminar of the International Association for Tibetans Studies, pp. 275-287.

Chos kyi dbang phyug. 1979. Gu ru chos dbang gi rang rnam dang zhal gdams. Paro: Ugyen Tempai Gyeltsen.

Bradburn, Leslie 1995. Masters of the Nyingma Lineage. Cazadero: Dharma Publications, p. 136 ff.

Dpa' bo gtsug lag 'phreng ba. 1980 (1564). Chos 'byung mkha's pa'i dga' ston. Delhi: Karmapa chodey gyelwae sungrab partun khang.

Karma mi 'gyur dbang rgyal. 1978. Gter bton brgya rtsa'i mtshan sdom gsol 'debs chos rgyal bkra shis stobs rgyal gyi mdzad pa'i 'grel pa lo rgyus gter bton chos 'byung. Darjeeling: Taklung Tsetrul Rinpoche Pema Wangyal, Orgyan Kunsang Chokhor Ling, p. 27.2 ff

'Jam dbyang mkhyen brtse'i dbang po. 1972. Gangs can gyi yul du byon pa'i lo pan rnams kyi mtshan tho rags rim tshigs bcad du bsdebs pa ma ha mandita ta shi la ratna'i gsung. In The collected works (gsung 'bum) of the great 'Jam dbyangs mkhyen brtse'i dbang po, v. 19, pp. 1-476. Gangtok: Gonpo Tseten, p. 103a ff.

Jakob Leschly August 2007