Vajrapāṇi

Vajrapāṇi (Tib., Phyag na rdo rje Chagna dorje)

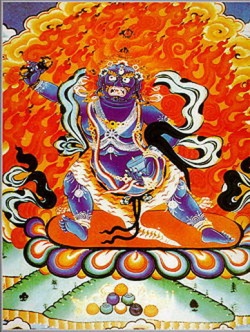

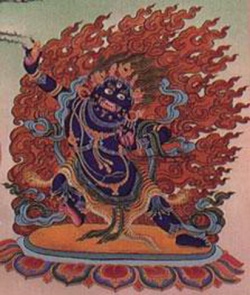

One of the eight great Bodhisattvas, especially associated with the transmission of tantric teachings. His name derives from the thunderbolt (vajra) which he holds in his hand (pāṇi) as his emblem. Iconographically, he is encountered in a yellow peaceful form or a dark blue wrathful forms'

In Sanskrit, vajrapāṇi means "he who has a vajra in hand." The word vajra refers to a thunderbolt, thunder crash, or lightning flash, and to its embodiment in unbreakable diamond (cf. the Tibetan neologistic translation Rdo rje dor je, "Lord of Stones") and the invincible weapon made thereof. Vajra is linguistically related to its Indo-European cousin, the Zoroastrian Zend vazra, Mithra's "club" (cf. Vedic Mitra), and the English cognates vigor, wacker, and wake.

In pre-Buddhist Indian literature, the vajra is wielded by powerful gods, above all Indra, lord of the gods, sky, and rains. From the Ṛgveda onward, Indra's attribute is the vajra. Nevertheless, while the Ṛgveda often refers to vajrabāhu : (vajra in arm) and vajrahasta (vajra in hand), their synonym, vajrapāṇi, is not found before the Ṣaḍviṃśabrāhmaṇa.

The vajra's bearer has close correspondents in Greek, Roman, and northern European mythology. Zeus and Jupiter, kings of the gods and sky gods, hold the thunderbolt, while the Norse Þórr (Thor) brandishes a meteoric hammer that flashes lightning. Greco-Roman depictions of the bundle of thunder and lightning are barely distinguishable from the double-ended trident vajra used today across the northern Buddhist world. A Buddhist legend explains the adapted form, since the Buddha had grasped Indra's weapon and blunted it, forcing the aggressive open prongs together to create a peaceful regal scepter.

Vajrapāṇi is one of the earliest bodhisattvas of Mahayana Buddhism. He is the protector and guide of the Buddha, and rose to symbolize the Buddha's power.

On the popular level, Vajrapani, Holder of the Thunderbolt Scepter (symbolizing the power of compassion), is the Bodhisattva who represents the power of all the Buddhas, just as Avalokitesvara represents their great compassion, Manjushri their wisdom, and Tara their miraculous deeds. For the yogi, Vajrapani is a means of accomplishing fierce determination and symbolizes unrelenting effectiveness in the conquest of negativity. His taut posture is the active warrior pose (pratayalidha), based on an archer's stance but resembling the en garde position in Western fencing. His outstretched right hand brandishes a vajra and his left hand deftly holds a lasso - with which he binds demons. He wears a skull crown with his hair standing on end. His expression is wrathful and he has a third eye. Around his neck is a serpent necklace and his loin cloth is made up of the skin of a tiger, whose head can be seen on his right knee.

The Pali Canon's Ambattha Suttanta tells of one instance of him protecting the Buddha's honor. A young Brahmin named Ambatha visited the Buddha and insulted him by saying the Shaykya clan (the enlightened one's family) were abjects who should revere the Brahmins.

In return, the Buddha asked the Brahmin if his family was descended from a “Shakya slave girl”. However, Ambatha further insulted the Buddha by not answering his question. When he failed to answer the question for a second time, the Buddha warned him that his head would be smashed to bits if he failed to do so a third time. Ambatha was frightened when he saw Vajrapani manifest above the Buddha's head ready to strike the Brahmin down with his thunderbolt.

He quickly confirmed the truth. According to the Pancavimsatisahasrika and Astasahasrika Prajnaparamita any Bodhisattva on the path to Buddhahood is eligible for Vajrapani's protection, making them invincible to any attacks "by either men or ghosts".

The Mantra oṃ vajrapāṇi hūṃ phaṭ is associated with Vajrapani. His Seed Syllable is hūṃ. Just as Buddhaghosa associated Vajrapani with the Hindu god Indra, his first representations in India were identified with the thunder deity. As Buddhism expanded in Central Asia, and fused with Hellenistic influences into Greco-Buddhism, the Greek hero Hercules was adopted to represent Vajrapani. He was then typically depicted as a hairy, muscular athlete, wielding a short "diamond" club. Mahayana Buddhism then further spread to China, Korea and Japan from the 6th century.

In Japan, Vajrapani is known as Shukongōshin "Diamond rod-wielding God"), and has been the inspiration for the Niō (Benevolent kings), the wrath-filled and muscular guardian god of the Buddha, standing today at the entrance of many Buddhist temples under the appearance of frightening wrestler-like statues.

Some suggest that the war deity Kartikeya, who bears the title Skanda is also a manifestation of Vajrapani, who bears some resemblance to Skanda because they both wield vajras as weapons and are portrayed with flaming halos. He is also connected through Vajrapani through a theory to his connection to Greco-Buddhism, as Wei Tuo's image is reminiscent of the Heracles depiction of Vajrapani.

Mañjuśrī is a bodhisattva associated with transcendent wisdom (Skt. prajñā) in Mahāyāna Buddhism. In Esoteric Buddhism he is also taken as a meditational deity. The Sanskrit name Mañjuśrī can be translated as "Gentle Glory". Mañjuśrī is also known by the fuller Sanskrit name of Mañjuśrīkumārabhūta.

In Mahāyāna Buddhism, Scholars have identified Mañjuśrī as the oldest and most significant bodhisattva in Mahāyāna literature.

Mañjuśrī is first referred to in early Mahāyāna texts such as the Prajñāpāramitā sūtras and through this association very early in the tradition he came to symbolize the embodiment of prajñā (transcendent wisdom). The Lotus Sūtra assigns him a pure land called Vimala, which according to the Avataṃsaka Sūtra is located in the East. His pure land is predicted to be one of the two best pure lands in all of existence in all the past, present and future.

When he attains buddhahood his name will be Universal Sight. In the Lotus Sūtra, Mañjuśrī also leads the Nāga King's daughter to enlightenment. He also figures in the Vimalakīrti Nirdeśa Sūtra in a debate with Bodhisattva Vimalakīrti. An example of a wisdom teaching of Bodhisattva Mañjuśrī can be found in the Mañjuśrī Spoken Mahāprajñāpāramitā Sūtra (Taishō T08N232). This sūtra contains a dialogue between Mañjuśrī and the Buddha on the One Practice Samādhi (Skt.

Ekavyūha Samādhi). Master Sheng-yen renders the following teaching of Mañjuśrī, for entering samādhi naturally through transcendent wisdom:Within Esoteric Buddhism, Mañjuśrī is a meditational deity, and considered a fully enlightened Buddha. In the Shingon school of Esoteric Buddhism, he is one of the thirteen deities to whom disciples devote themselves. He figures extensively in many Esoteric Buddhist texts such as the Mañjuśrī-mūla-kalpa. and the Mañjuśrīnāmasaṃgīti. His consort in some traditions is Saraswati.

Je Tsongkhapa, who founded the Gelug sect of Tibetan Buddhism, is said to have received his teachings from visions of Mañjuśrī.

Iconography

Mañjuśrī is depicted as a male bodhisattva wielding a flaming sword in his right hand, representing the realization of transcendent wisdom which cuts down ignorance and duality. The scripture supported by thelotus held in his left hand is a Prajñāpāramitā sūtra, representing his attainment of ultimate realization from the blossoming of wisdom. Mañjuśrī is often depicted as riding on a blue lion, or sitting on the skin of a lion. This represents the use of wisdom to tame the mind, which is compared to riding or subduing a ferocious lion.

He is one of the Four Great Bodhisattvas of Chinese Buddhism, the other three being: BodhisattvaKṣitigarbha, Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara, and Bodhisattva Samantabhadra. In China, he is often paired with Bodhisattva Samantabhadra.

In Tibetan Buddhism he sometimes is depicted in a trinity with Avalokiteśvara and Vajrapāṇi.

Mantras

A mantra commonly associated with Mañjuśrī is the following:

oṃ a ra pa ca na dhīḥ

ntra is believed to enhance wisdom and improve one's skills in debating, memory, writing, and other literary abilities. "Dhīḥ" is the seed syllable of the mantra and is chanted with greater emphasis.

In Buddhist Cultures

In China

Wutai Shan in Shanxi, one of the Four Sacred Mountains of Buddhism in China, which also had strong associations for Taoists, is considered by Chinese Buddhists to be the earthly abode of Mañjuśrī. He was said to bestow spectacular visionary experiences to those on selected mountain peaks and caves there. In Wutai Shan's Foguang Temple, the Manjusri Hall on the right side of its main hall was recognized to have been built in 1137 during the Jin Dynasty. The hall was thoroughly studied, mapped, and first photographed by early twentieth century Chinese architects Liang Sicheng and Lin Huiyin. These made it a popular place of pilgrimage, but patriarchs including Linji and Yun-men declared the mountain off limits. Being in the North of China and revered, Mount Wutai was also associated with the Northern lineages of Zen.

In Tibet

In Tibetan Buddhism, Mañjuśrī manifests in a number of different Tantric forms. Yamāntaka(meaning 'terminator of Yama i.e. Death') is the wrathful manifestation of Mañjuśrī, popular within the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism. Other variations upon his traditional form as Mañjuśrī include Guhya-Manjusri, Guhya-Manjuvajra, and Manjuswari. The two former appearances are generally accompanied by a shakti deity embracing the main figure, symbolising union of form and spirit, matter and energy.

In Manchuria

According to a legend, Nurhaci, a military leader of the Jurchen tribes in Northeast China and founder of what became the Chinese imperial Qing Dynasty, believed himself to be a reincarnation of Mañjuśrī. He therefore is said to have renamed his tribe the Manchu.

In Nepal

According to Swayambhu Purana, the Kathmandu Valley was once a lake. It is believed that Mañjuśrī saw a lotus flower in the center of the lake and cut a gorge at Chovar to allow the lake to drain. The place where the lotus flower settled became Swayambhunath Stupa and the valley thus became habitable.

In Japan

An early tradition held that Mañjuśrī (Monju or Monjushiri in Japanese) "invented" nanshoku or male homosexual love

Avalokiteśvara (Sanskrit: अवलोकितेश्वर , Bengali: অবলোকিতেশ্বর, lit. "Lord who looks down",Chinese: 觀世音) is a bodhisattva who embodies the compassion of all Buddhas. He is one of the more widely revered bodhisattvas in mainstream Mahayana Buddhism. In China and its sphere of cultural influence, Avalokiteśvara is often depicted in a female form known asGuan Yin. (However, in Taoist mythology, Guan Yin has other origination stories which are unrelated to Avalokiteśvara.).

In India, Avalokitesvara is also referred to as Padmapāni ("Holder of the Lotus"), Lokeśvara ("Lord of the World") or Tara. In Tibetan, Avalokiteśvara is known as Chenrezig, སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་ (Wylie: spyan ras gzigs), and is said to be incarnated in the Dalai Lama , Karmapa and other high Lamas. In Mongolia, he is called Megjid Janraisig, Xongsim Bodisadv-a, or Nidüber Üjegči.

Etymology

The name Avalokiteśvara is made of the following parts: the verbal prefix ava, which means "down"; lokita, a past participle of the verb lok ("to notice, behold, observe"), here used in an active sense (an occasional irregularity of Sanskrit grammar); and finally īśvara, "lord", "ruler", "sovereign" or "master". In accordance with the rules of sound combination,a+iśvara becomes eśvara. Combined, the parts mean "lord who gazes down (at the world)". The word loka ("world") is absent from the name, but the phrase is implied.

It was initially thought that the Chinese mis-transliterated the word Avalokiteśvara as Avalokitasvara which explained why Xuanzang translated it as Guan Zizai instead of Guan Yin. However, according to recent research, the original form was indeed Avalokitasvara with the ending a-svara ("sound, noise"), which means "sound perceiver", literally "he who looks down upon sound" (i.e., the cries of sentient beings who need his help; a-svara can be glossed as ahr-svara, "sound of lamentation"). This is the exact equivalent of the Chinese translation Guan Yin. This etymology was furthered in the Chinese by the tendency of some Chinese translators, notably Kumarajiva, to use the variant Guan Shih Yin, literally "he who perceives the world's lamentations"--wherein lok was read as simultaneously meaning both "to look" and "world" (loka, Chinese: shih). This name was later supplanted by the form containing the ending -īśvara, which does not occur in Sanskrit before the seventh century. The original form Avalokitasvara already appears in Sanskrit fragments of the fifth century.

The original meaning of the name fits the Buddhist understanding of the role of a bodhisattva. The reinterpretation presenting him as an īśvara shows a strong influence of Shaivism, as the term īśvara was usually connected to the Hindu notion of a creator god and ruler of the world. Attributes of such a god were transmitted to the bodhisattva, but the mainstream of the Avalokiteśvara worshippers upheld the Buddhist rejection of the doctrine of any creator god.

An etymology of the Tibetan name Chenrezig is chen (eye), re (continuity) and zig (to look). This gives the meaning of one who always looks upon all beings (with the eye of compassion).

Mahayana account

According to Mahayana doctrine, Avalokiteśvara is the bodhisattva who has made a great vow to listen to the prayers of all sentient beings in times of difficulty, and to postpone his own Buddhahood until he has assisted every being on Earth in achieving nirvana. Mahayana sutras associated with Avalokiteśvara include the Heart Sutra (as disciple of the historical Buddha Shakyamuni) and the Lotus Sutra, particularly the 25th chapter (妙法蓮華經觀世音菩薩普門品第二十五/miào fǎ lián huá jīng guān shì yīn pú sà pŭ mén pǐn dì èr shí wŭ/"Perceiver of the World’s Sounds" or "Universal Gateway"/kanzeon bosatsu fumon hon), which is sometimes referred to as the Avalokiteśvara Sutra.

Six forms of Avalokiteśvara in Mahayana (defined by Tian-tai, terrace):

<poem>

1. great compassion,

2. great loving-kindness,

3. lion-courage,

4. universal light,

5. leader amongst gods and men,

6. the great omnipresent Brahman.

Each of this bodhisattva's six qualities of pity, etc., breaks the hindrances respectively of the (6 realms) hells, pretas (hungry ghost), animals, asuras (demi god), men, and devas.

Also known as Tsen Ti Bodhisattva in Chinese (1000 hands and 1000 eyes).

Vajrayana account

Part of a series onTibetan Buddhism

Guru Rinpoche - Padmasambhava statue.jpg

Bronze statue of Padmapāni, circa 1100

In the Tibetan tradition, Avalokiteśvara is seen as arising from two sources. One is the relative source, where in a previous eon (kalpa) a devoted, compassionate Buddhist monk became a bodhisattva, transformed in the present kalpa into Avalokiteśvara. That is not in conflict, however, with the ultimate source, which is Avalokiteśvara as the universal manifestation of compassion. The bodhisattva is viewed as the anthropomorphised vehicle for the actual deity, serving to bring about a better understanding of Avalokiteśvara to humankind.

Seven forms of Avalokiteśvara in esoteric Buddhism:

1. Amoghapāśa. not empty (or unerring) net, or lasso.

2. Vara-sahasrabhuja-locana/Sahasrabhujasahasranetra, 1000-hand and 1000-eye,

3. Hayagriva, horseheaded,

4. Ekadasamukha,11-faced,

5. Cundi,

6. Cintamani-cakra;wheel of sovereign power,

7. arya Lokiteśvara, the Holy sovereign beholder of the world (loka), a translation of īśvara, means "ruler" or "sovereign", holy one.

Theravada account

Although mainstream Theravada does not worship any of the Mahayana bodhisattvas, Avalokiteśvara is popularly worshiped in Burma, where she is called Lokanat, and Thailand, where she is called Lokesvara.

Western scholars have not reached a consensus on the origin of the reverence for Avalokiteśvara. Some have suggested that Avalokiteśvara, along with many other supernatural beings in Buddhism, was a borrowing or absorption by Mahayana Buddhism of one or more Hindu deities, in particular Shiva or Vishnu(though the reason for this suggestion is because the current name of the bodhisattva not the original one.)

The Japanese scholar Shu Hikosaka on the basis of his study of Buddhist scriptures, ancient Tamil literary sources, as well as field survey, proposes the hypothesis that, the ancient mount Potalaka, the residence of Avalokiteśvara described in the Gandavyuha Sutra and Xuanzang’s Records, is the real mountain Potikai or Potiyil situated at Ambasamudram in Tirunelveli district, Tamil Nadu. Shu also says that mount Potiyil/Potalaka has been a sacred place for the people of South India from time immemorial. With the spread of Buddhism in the region beginning at the time of the great king Aśoka in the third century B.C.E., it became a holy place also for Buddhists who gradually became dominant as a number of their hermits settled there. The local people, though, mainly remained followers of the Hindu religion. The mixed Hindu-Buddhist cult culminated in the formation of the figure of Avalokiteśvara .

In Theravada, Lokeśvara, "the lord, ruler or sovereign beholder of the world", name of a Buddha; probably a development of the idea of Brahmā, Vishnu or Śiva as lokanātha, "lord of worlds". In Indo-China especially it refers to Avalokiteśvara, whose image or face, in masculine form, is frequently seen, e.g., at Angkor. A Buddha under whom Amitābha, in a previous existence, entered into the ascetic life and made his forty-eight vows.

Tibetan Buddhism relates Chenrezig to the six-syllable mantra Om Mani Padme Hum. Thus, Chenrezig is also called Shadakshari ("Lord of the Six Syllables"). The connection between this famous mantra and Avalokiteśvara already occurs in the Karandavyuha Sutra (probably late fourth or early fifth century), one of the first Buddhist works to have reached Tibet (before the end of the fifth century).

In Shingon Buddhism, the mantra used to praise Avalokiteśvara is On Aro-rikya Sowaka, in Sanskrit: Om Arolik Svāhā (Oh, Unstained One, Hail!).

The Great Compassion Mantra is an 82 syllable mantra spoken by Avalokiteśvara to the assembly of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, and extolling the merits of chanting the mantra. This mantra is popular in China, Japan and Taiwan.

The thousand arms of Avalokiteśvara

One prominent Buddhist story tells of Avalokiteśvara vowing never to rest until he had freed all sentient beings from samsara. Despite strenuous effort, he realizes that still many unhappy beings were yet to be saved. After struggling to comprehend the needs of so many, his head splits into eleven pieces. Amitabha Buddha, seeing his plight, gives him eleven heads with which to hear the cries of the suffering. Upon hearing these cries and comprehending them, Avalokiteśvara attempts to reach out to all those who needed aid, but found that his two arms shattered into pieces. Once more, Amitabha comes to his aid and invests him with a thousand arms with which to aid the suffering multitudes.

Many Himalayan versions of the tale include eight arms with which Avalokiteśvara skillfully upholds the dharma, each possessing its own particular implement, while more Chinese-specific ones give varying accounts of this number.

The Bao'en Temple located in northwestern Sichuan province, China has an outstanding wooden image of the thousand armed Avalokiteśvara, an example of Ming Dynasty decorative sculpture.

Tibetan Buddhist beliefs concerning Chenrezig

Avalokiteśvara is an important deity in Tibetan Buddhism, and is regarded in the Vajrayanateachings as a Buddha.In the Mahayana teachings he is in general regarded as a high-level Bodhisattva. The Dalai Lama is considered by the Gelugpa sect and many other Tibetan Buddhists to be the primary earthly manifestation of Chenrezig. The Karmapa is considered by the Karma Kagyu sect to be Chenrezig's primary manifestation. It is said that Padmasambhava prophesied that Avalokiteśvara will manifest himself in the Tulku lineages of the Dalai Lamas and the Karmapas.Another Tibetan source explains that Buddha Amithaba gave to one of his two main disciples, Avalokiteśvara, the task to take upon himself the burden of caring for Tibet. That is why he has manifested himself not only as spiritual teachers in Tibet but also in the form of kings (like Trisong Detsen) or ministers.

Other manifestations popular in Tibet include Sahasra-bhuja (a form with a thousand arms) and Ekādaśamukha (a form with eleven faces).

In Tibetan Buddhism, Tara came into existence from a single tear shed by Chenrezig. When the tear fell to the ground it created a lake, and a lotus opening in the lake revealed Tara. In another version of this story, Tara emerges from the heart of Chenrezig. In either version, it is Chenrezig's outpouring of compassion which manifests Tara as a being.

Avalokiteśvara has an extraordinarily large number of manifestations in different forms. Some of the more commonly mentioned forms include: </poem>