Difference between revisions of "Vedanta and Buddhism A Comparative Study"

m (Text replacement - "a stream" to "a stream") |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

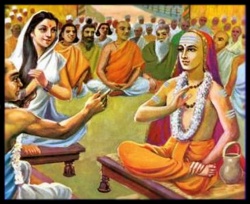

[[File:Hankara.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Hankara.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The present treatise by Prof. Dr. H.V. Glasenapp has been selected for reprint particularly in [[view]] of the excellent elucidation of the [[Anatta]] [[Doctrine]] which it contains. The treatise, in its German original, appeared in 1950 in the Proceeding of the "Akademie der Wissenschaften and Literatur" (Academy of Sciences and Literature). The present [[selection]] from that original is based on the abridged translations published in "The [[Buddhist]]," Vol.XXI, No. 12 (Colombo 1951). Partial use has also been made of a different [[selection]] and translation which appeared in "The [[Middle Way]]," Vol. XXXI, No. 4 ({{Wiki|London}} 1957). | + | The {{Wiki|present}} treatise by Prof. Dr. H.V. Glasenapp has been selected for reprint particularly in [[view]] of the {{Wiki|excellent}} elucidation of the [[Anatta]] [[Doctrine]] which it contains. The treatise, in its {{Wiki|German}} original, appeared in 1950 in the Proceeding of the "Akademie der Wissenschaften and Literatur" ({{Wiki|Academy}} of {{Wiki|Sciences}} and {{Wiki|Literature}}). The {{Wiki|present}} [[selection]] from that original is based on the abridged translations published in "The [[Buddhist]]," Vol.XXI, No. 12 ({{Wiki|Colombo}} 1951). Partial use has also been made of a different [[selection]] and translation which appeared in "The [[Middle Way]]," Vol. XXXI, No. 4 ({{Wiki|London}} 1957). |

| − | The author of this treatise is an eminent {{Wiki|Indologist}} of Western {{Wiki|Germany}}, formerly of the University of Koenigsberg, now occupying the indological chair of the University of Tuebingen. Among his many [[scholarly]] publications are [[books]] on [[Buddhism]], [[Hinduism]], [[Jainism]] and on comparative [[religion]]. | + | The author of this treatise is an {{Wiki|eminent}} {{Wiki|Indologist}} of {{Wiki|Western}} {{Wiki|Germany}}, formerly of the {{Wiki|University}} of Koenigsberg, now occupying the indological chair of the {{Wiki|University}} of Tuebingen. Among his many [[scholarly]] publications are [[books]] on [[Buddhism]], [[Hinduism]], [[Jainism]] and on comparative [[religion]]. |

— [[Buddhist]] Publication {{Wiki|Society}} | — [[Buddhist]] Publication {{Wiki|Society}} | ||

{{Wiki|Vedanta}} and [[Buddhism]] | {{Wiki|Vedanta}} and [[Buddhism]] | ||

| − | {{Wiki|Vedanta}} and [[Buddhism]] are the highlights of [[Indian]] [[philosophical]] [[thought]]. Since both have grown in the same [[spiritual]] soil, they share many basic ideas: both of them assert that the [[universe]] shows a periodical succession of arising, [[existing]] and vanishing, and that this process is without beginning and end. They believe in the [[causality]] which binds the result of an [[action]] to its [[cause]] ([[karma]]), and in [[rebirth]] [[conditioned]] by that nexus. Both are convinced of the transitory, and therefore [[sorrowful]] character, of {{Wiki|individual}} [[existence]] in the [[world]]; they hope to attain gradually to a redeeming [[knowledge]] through [[renunciation]] and [[meditation]] and they assume the possibility of a blissful and serene state, in which all [[worldly]] imperfections have vanished for ever. The original [[form]] of these two [[doctrines]] shows however strong contrast. The early {{Wiki|Vedanta}}, formulated in most of the older and middle {{Wiki|Upanishads}}, in some passages of the {{Wiki|Mahabharata}} and the {{Wiki|Puranas}}, and still alive today (though greatly changed) as the basis of several Hinduistic systems, teaches an ens realissimum (an entity of highest [[reality]]) as the [[primordial]] [[cause]] of all [[existence]], from which everything has arisen and with which it again merges, either temporarily or for ever. | + | {{Wiki|Vedanta}} and [[Buddhism]] are the highlights of [[Indian]] [[philosophical]] [[thought]]. Since both have grown in the same [[spiritual]] soil, they share many basic [[ideas]]: both of them assert that the [[universe]] shows a periodical succession of [[arising]], [[existing]] and vanishing, and that this process is without beginning and end. They believe in the [[causality]] which binds the result of an [[action]] to its [[cause]] ([[karma]]), and in [[rebirth]] [[conditioned]] by that {{Wiki|nexus}}. Both are convinced of the transitory, and therefore [[sorrowful]] [[character]], of {{Wiki|individual}} [[existence]] in the [[world]]; they {{Wiki|hope}} to attain gradually to a redeeming [[knowledge]] through [[renunciation]] and [[meditation]] and they assume the possibility of a blissful and [[serene]] [[state]], in which all [[worldly]] imperfections have vanished for ever. The original [[form]] of these two [[doctrines]] shows however strong contrast. The early {{Wiki|Vedanta}}, formulated in most of the older and middle {{Wiki|Upanishads}}, in some passages of the {{Wiki|Mahabharata}} and the {{Wiki|Puranas}}, and still alive today (though greatly changed) as the basis of several [[Hinduistic]] systems, teaches an ens realissimum (an [[entity]] of [[highest]] [[reality]]) as the [[primordial]] [[cause]] of all [[existence]], from which everything has arisen and with which it again merges, either temporarily or for ever. |

| − | With the monistic [[metaphysics]] of the {{Wiki|Vedanta}} contrasts the pluralistic [[Philosophy]] of Flux of the [[early Buddhism]] of the [[Pali]] texts which up to the present [[time]] flourishes in {{Wiki|Ceylon}}, [[Burma]] and Siam. It teaches that in the whole [[empirical]] [[reality]] there is nowhere anything that persists; neither material nor [[mental]] substances [[exist]] independently by themselves; there is no original entity or [[primordial]] [[Being]] in whatsoever [[form]] it may be [[imagined]], from which these substances might have developed. On the contrary, the manifold [[world]] of [[mental]] and material [[elements]] arises solely through the [[causal]] co-operation of the transitory factors of [[existence]] ([[dharma]]) which depend functionally upon each other, that is, the material and [[mental]] [[universe]] arises through the concurrence of forces that, according to the [[Buddhists]], are not reducible to something else. It is therefore obvious that [[deliverance]] from the [[Samsara]], i.e., the sorrow-laden round of [[existence]], cannot consist in the re-absorption into an [[eternal]] [[Absolute]] which is at the [[root]] of all manifoldness, but can only be achieved by a complete [[extinguishing]] of all factors which [[condition]] the processes constituting [[life]] and [[world]]. The [[Buddhist]] [[Nirvana]] is, therefore, not the [[primordial]] ground, the [[eternal]] [[essence]], which is at the basis of everything and [[form]] which the whole [[world]] has arisen (the [[Brahman]] of the {{Wiki|Upanishads}}) but the reverse of all that we [[know]], something altogether different which must be characterized as a [[nothing]] in relation to the [[world]], but which is [[experienced]] as highest [[bliss]] by those who have attained to it ([[Anguttara Nikaya]], Navaka-nipata 34). Vedantists and [[Buddhists]] have been fully aware of the gulf between their [[doctrines]], a gulf that cannot be bridged over. According to [[Majjhima Nikaya]], [[Sutta]] 22, a [[doctrine]] that proclaims "The same is the [[world]] and the [[self]]. This I shall be after [[death]]; imperishable, permanent, [[eternal]]!" (see Brh. UP. 4, 4, 13), was styled by the [[Buddha]] a perfectly foolish [[doctrine]]. On the other side, the Katha-Upanishad (2, 1, 14) does not see a way to [[deliverance]] in the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|theory}} of [[dharmas]] (impersonal processes): He who supposes a profusion of particulars gets lost like rain [[water]] on a mountain slope; the truly [[wise]] man, however, must realize that his [[Atman]] is at one with the [[Universal]] [[Atman]], and that the former, if [[purified]] from dross, is [[being]] absorbed by the latter, "just as clear [[water]] poured into clear [[water]] becomes one with it, indistinguishably." | + | With the {{Wiki|monistic}} [[metaphysics]] of the {{Wiki|Vedanta}} contrasts the pluralistic [[Philosophy]] of Flux of the [[early Buddhism]] of the [[Pali]] texts which up to the {{Wiki|present}} [[time]] flourishes in {{Wiki|Ceylon}}, [[Burma]] and {{Wiki|Siam}}. It teaches that in the whole [[empirical]] [[reality]] there is nowhere anything that persists; neither material nor [[mental]] {{Wiki|substances}} [[exist]] {{Wiki|independently}} by themselves; there is no original [[entity]] or [[primordial]] [[Being]] in whatsoever [[form]] it may be [[imagined]], from which these {{Wiki|substances}} might have developed. On the contrary, the manifold [[world]] of [[mental]] and material [[elements]] arises solely through the [[causal]] co-operation of the transitory factors of [[existence]] ([[dharma]]) which depend functionally upon each other, that is, the material and [[mental]] [[universe]] arises through the concurrence of forces that, according to the [[Buddhists]], are not reducible to something else. It is therefore obvious that [[deliverance]] from the [[Samsara]], i.e., the sorrow-laden round of [[existence]], cannot consist in the re-absorption into an [[eternal]] [[Absolute]] which is at the [[root]] of all manifoldness, but can only be achieved by a complete [[extinguishing]] of all factors which [[condition]] the {{Wiki|processes}} constituting [[life]] and [[world]]. The [[Buddhist]] [[Nirvana]] is, therefore, not the [[primordial]] ground, the [[eternal]] [[essence]], which is at the basis of everything and [[form]] which the whole [[world]] has arisen (the [[Brahman]] of the {{Wiki|Upanishads}}) but the reverse of all that we [[know]], something altogether different which must be characterized as a [[nothing]] in [[relation]] to the [[world]], but which is [[experienced]] as [[highest]] [[bliss]] by those who have [[attained]] to it ([[Anguttara Nikaya]], Navaka-nipata 34). Vedantists and [[Buddhists]] have been fully {{Wiki|aware}} of the gulf between their [[doctrines]], a gulf that cannot be bridged over. According to [[Majjhima Nikaya]], [[Sutta]] 22, a [[doctrine]] that proclaims "The same is the [[world]] and the [[self]]. This I shall be after [[death]]; imperishable, [[permanent]], [[eternal]]!" (see Brh. UP. 4, 4, 13), was styled by the [[Buddha]] a perfectly [[foolish]] [[doctrine]]. On the other side, the Katha-Upanishad (2, 1, 14) does not see a way to [[deliverance]] in the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|theory}} of [[dharmas]] ({{Wiki|impersonal}} {{Wiki|processes}}): He who supposes a profusion of particulars gets lost like [[rain]] [[water]] on a mountain slope; the truly [[wise]] man, however, must realize that his [[Atman]] is at one with the [[Universal]] [[Atman]], and that the former, if [[purified]] from dross, is [[being]] absorbed by the [[latter]], "just as clear [[water]] poured into clear [[water]] becomes one with it, indistinguishably." |

[[File:Prabhuji.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Prabhuji.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | {{Wiki|Vedanta}} and [[Buddhism]] have lived side by side for such a long [[time]] that obviously they must have influenced each other. The strong predilection of the [[Indian]] [[mind]] for a [[doctrine]] of [[universal]] unity ({{Wiki|monism}}) has led the representatives of [[Mahayana]] to conceive [[Samsara]] and [[Nirvana]] as two aspects of the same and single true [[reality]]; for [[Nagarjuna]] the [[empirical]] [[world]] is a mere appearance, as all [[dharmas]], [[manifest]] in it, are perishable and [[conditioned]] by other [[dharmas]], without having any independent [[existence]] of their own. Only the indefinable "[[Voidness]]" ([[sunyata]]) to be grasped in [[meditation]], and [[realized]] in [[Nirvana]], has true [[reality]]. | + | {{Wiki|Vedanta}} and [[Buddhism]] have lived side by side for such a long [[time]] that obviously they must have influenced each other. The strong predilection of the [[Indian]] [[mind]] for a [[doctrine]] of [[universal]] {{Wiki|unity}} ({{Wiki|monism}}) has led the representatives of [[Mahayana]] to [[conceive]] [[Samsara]] and [[Nirvana]] as two aspects of the same and single true [[reality]]; for [[Nagarjuna]] the [[empirical]] [[world]] is a mere [[appearance]], as all [[dharmas]], [[manifest]] in it, are perishable and [[conditioned]] by other [[dharmas]], without having any {{Wiki|independent}} [[existence]] of their [[own]]. Only the indefinable "[[Voidness]]" ([[sunyata]]) to be grasped in [[meditation]], and [[realized]] in [[Nirvana]], has true [[reality]]. |

| − | This so-called Middle [[Doctrine]] of [[Nagarjuna]] remains true to the [[Buddhist]] principle that there can be nowhere a [[substance]], in so far as [[Nagarjuna]] sees the last unity as a kind of [[Wikipedia:Abyss (religion)|abyss]], characterized only negatively, which has no genetic relation to the [[world]]. [[Asanga]] and [[Vasubandhu]], however, in their [[doctrine]] of [[Consciousness Only]], have abandoned the [[Buddhist]] principle of denying a positive [[reality]] which is at the [[root]] all [[phenomena]], and in doing so, they have made a further approach to {{Wiki|Vedanta}}. To that mahayanistic school of [[Yogacaras]], the highest [[reality]] is a [[pure]] and undifferentiated [[spiritual]] [[element]] that represents the non- [[relative]] [[substratum]] of all [[phenomena]]. To be sure, they thereby do not assert, as the (older) {{Wiki|Vedanta}} does, that the ens realissimum (the highest [[essence]]) is identical with the [[universe]], the relation between the two is rather [[being]] defined as "[[being]] neither different nor not different." It is only in the later [[Buddhist]] systems of the Far East that the undivided, [[absolute]] [[consciousness]] is taken to be the basis of the manifold [[world]] of [[phenomena]]. But in contrast to the older {{Wiki|Vedanta}}, it is never maintained that the [[world]] is an unfoldment from the unchangeable, [[eternal]], blissful [[Absolute]]; [[suffering]] and [[passions]], [[manifest]] in the [[world]] of plurality, are rather traced back to [[worldly]] [[delusion]]. | + | This so-called Middle [[Doctrine]] of [[Nagarjuna]] remains true to the [[Buddhist]] [[principle]] that there can be nowhere a [[substance]], in so far as [[Nagarjuna]] sees the last {{Wiki|unity}} as a kind of [[Wikipedia:Abyss (religion)|abyss]], characterized only negatively, which has no {{Wiki|genetic}} [[relation]] to the [[world]]. [[Asanga]] and [[Vasubandhu]], however, in their [[doctrine]] of [[Consciousness Only]], have abandoned the [[Buddhist]] [[principle]] of denying a positive [[reality]] which is at the [[root]] all [[phenomena]], and in doing so, they have made a further approach to {{Wiki|Vedanta}}. To that [[mahayanistic]] school of [[Yogacaras]], the [[highest]] [[reality]] is a [[pure]] and undifferentiated [[spiritual]] [[element]] that represents the non- [[relative]] [[substratum]] of all [[phenomena]]. To be sure, they thereby do not assert, as the (older) {{Wiki|Vedanta}} does, that the ens realissimum (the [[highest]] [[essence]]) is [[identical]] with the [[universe]], the [[relation]] between the two is rather [[being]] defined as "[[being]] neither different nor not different." It is only in the later [[Buddhist]] systems of the {{Wiki|Far East}} that the undivided, [[absolute]] [[consciousness]] is taken to be the basis of the manifold [[world]] of [[phenomena]]. But in contrast to the older {{Wiki|Vedanta}}, it is never maintained that the [[world]] is an unfoldment from the unchangeable, [[eternal]], blissful [[Absolute]]; [[suffering]] and [[passions]], [[manifest]] in the [[world]] of plurality, are rather traced back to [[worldly]] [[delusion]]. |

| − | On the other hand, the [[doctrines]] of later [[Buddhist philosophy]] had a far-reaching [[influence]] on {{Wiki|Vedanta}}. It is well known that Gaudapada, and other representatives of later {{Wiki|Vedanta}}, taught an illusionistic acosmism, for which true [[Reality]] is only "the eternally [[pure]], eternally [[awakened]], eternally redeemed" [[universal]] [[spirit]] whilst all manifoldness is only [[delusion]]; the [[Brahma]] has therefore not developed into the [[world]], as asserted by the older {{Wiki|Vedanta}}, but it forms only the world's unchangeable background, comparable to the white screen on which appear the changing images of an unreal shadow play. | + | On the other hand, the [[doctrines]] of later [[Buddhist philosophy]] had a far-reaching [[influence]] on {{Wiki|Vedanta}}. It is well known that [[Gaudapada]], and other representatives of later {{Wiki|Vedanta}}, [[taught]] an illusionistic acosmism, for which true [[Reality]] is only "the eternally [[pure]], eternally [[awakened]], eternally redeemed" [[universal]] [[spirit]] whilst all manifoldness is only [[delusion]]; the [[Brahma]] has therefore not developed into the [[world]], as asserted by the older {{Wiki|Vedanta}}, but it [[forms]] only the world's unchangeable background, comparable to the white screen on which appear the changing images of an unreal shadow play. |

| − | In my opinion, there was in later times, especially since the {{Wiki|Christian}} {{Wiki|era}}, much mutual [[influence]] of {{Wiki|Vedanta}} and [[Buddhism]], but originally the systems are diametrically opposed to each other. The [[Atman]] [[doctrine]] of the {{Wiki|Vedanta}} and the [[Dharma]] {{Wiki|theory}} of [[Buddhism]] exclude each other. The {{Wiki|Vedanta}} tries to establish an [[Atman]] as the basis of everything, whilst [[Buddhism]] maintains that everything in the [[empirical]] [[world]] is only a stream of passing [[Dharmas]] (impersonal and evanescent processes) which therefore has to be characterized as [[Anatta]], i.e., [[being]] without a persisting [[self]], without independent [[existence]]. | + | In my opinion, there was in later times, especially since the {{Wiki|Christian}} {{Wiki|era}}, much mutual [[influence]] of {{Wiki|Vedanta}} and [[Buddhism]], but originally the systems are diametrically opposed to each other. The [[Atman]] [[doctrine]] of the {{Wiki|Vedanta}} and the [[Dharma]] {{Wiki|theory}} of [[Buddhism]] exclude each other. The {{Wiki|Vedanta}} tries to establish an [[Atman]] as the basis of everything, whilst [[Buddhism]] maintains that everything in the [[empirical]] [[world]] is only a {{Wiki|stream}} of passing [[Dharmas]] ({{Wiki|impersonal}} and evanescent {{Wiki|processes}}) which therefore has to be characterized as [[Anatta]], i.e., [[being]] without a persisting [[self]], without {{Wiki|independent}} [[existence]]. |

[[File:Ankara.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Ankara.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Again and again [[scholars]] have tried to prove a closer connection between the [[early Buddhism]] of the [[Pali]] texts, and the {{Wiki|Vedanta}} of the {{Wiki|Upanishads}}; they have even tried to interpret [[Buddhism]] as a further development of the [[Atman]] [[doctrine]]. There are, e.g., two [[books]] which show that tendency: The {{Wiki|Vedantic}} [[Buddhism]] of the [[Buddha]], by J.G. Jennings (Oxford University Press, 1947), and in German [[language]], The [[Soul]] Problem of [[Early Buddhism]], by {{Wiki|Herbert Guenther}} (Konstanz 1949). | + | Again and again [[scholars]] have tried to prove a closer connection between the [[early Buddhism]] of the [[Pali]] texts, and the {{Wiki|Vedanta}} of the {{Wiki|Upanishads}}; they have even tried to interpret [[Buddhism]] as a further [[development]] of the [[Atman]] [[doctrine]]. There are, e.g., two [[books]] which show that tendency: The {{Wiki|Vedantic}} [[Buddhism]] of the [[Buddha]], by J.G. Jennings ({{Wiki|Oxford University Press}}, 1947), and in {{Wiki|German}} [[language]], The [[Soul]] Problem of [[Early Buddhism]], by {{Wiki|Herbert Guenther}} (Konstanz 1949). |

[[File:LCJ2.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:LCJ2.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The [[essential]] [[difference]] between the conception of [[deliverance]] in {{Wiki|Vedanta}} and in [[Pali]] [[Buddhism]] lies in the following ideas: {{Wiki|Vedanta}} sees [[deliverance]] as the [[manifestation]] of a state which, though obscured, has been [[existing]] from [[time]] immemorial; for the [[Buddhist]], however, [[Nirvana]] is a [[reality]] which differs entirely from all [[dharmas]] as [[manifested]] in [[Samsara]], and which only becomes effective, if they are abolished. To sum up: the Vedantin wishes to penetrate to the last [[reality]] which dwells within him as an [[immortal]] [[essence]], or seed, out of which everything has arisen. The follower of [[Pali]] [[Buddhism]], however, hopes by complete [[abandoning]] of all corporeality, all [[sensations]], all [[perceptions]], all [[Wikipedia:Volition (psychology)|volitions]], and acts of [[consciousness]], to realize a state of [[bliss]] which is entirely different from all that [[exists]] in the [[Samsara]]. | + | The [[essential]] [[difference]] between the {{Wiki|conception}} of [[deliverance]] in {{Wiki|Vedanta}} and in [[Pali]] [[Buddhism]] lies in the following [[ideas]]: {{Wiki|Vedanta}} sees [[deliverance]] as the [[manifestation]] of a [[state]] which, though obscured, has been [[existing]] from [[time]] immemorial; for the [[Buddhist]], however, [[Nirvana]] is a [[reality]] which differs entirely from all [[dharmas]] as [[manifested]] in [[Samsara]], and which only becomes effective, if they are abolished. To sum up: the [[Vedantin]] wishes to penetrate to the last [[reality]] which dwells within him as an [[immortal]] [[essence]], or seed, out of which everything has arisen. The follower of [[Pali]] [[Buddhism]], however, [[Wikipedia:Hope|hopes]] by complete [[abandoning]] of all corporeality, all [[sensations]], all [[perceptions]], all [[Wikipedia:Volition (psychology)|volitions]], and acts of [[consciousness]], to realize a [[state]] of [[bliss]] which is entirely different from all that [[exists]] in the [[Samsara]]. |

| − | After these introductory remarks we shall now discuss systematically the relation of original [[Buddhism]] and {{Wiki|Vedanta}}. | + | After these introductory remarks we shall now discuss systematically the [[relation]] of original [[Buddhism]] and {{Wiki|Vedanta}}. |

(1) First of all we have to clarify to what extent a [[knowledge]] of {{Wiki|Upanishadic}} texts may be assumed for the {{Wiki|canonical}} [[Pali]] [[scriptures]]. The five old prose {{Wiki|Upanishads}} are, on [[reasons]] of contents and [[language]], generally held to be pre-Buddhistic. The younger {{Wiki|Upanishads}}, in any case those beginning from Maitrayana, were certainly written at a [[time]] when [[Buddhism]] already existed. | (1) First of all we have to clarify to what extent a [[knowledge]] of {{Wiki|Upanishadic}} texts may be assumed for the {{Wiki|canonical}} [[Pali]] [[scriptures]]. The five old prose {{Wiki|Upanishads}} are, on [[reasons]] of contents and [[language]], generally held to be pre-Buddhistic. The younger {{Wiki|Upanishads}}, in any case those beginning from Maitrayana, were certainly written at a [[time]] when [[Buddhism]] already existed. | ||

| − | The number of passages in the [[Pali Canon]] dealing with {{Wiki|Upanishadic}} [[doctrines]], is very small. It is true that [[early Buddhism]] shares many [[doctrines]] with the {{Wiki|Upanishads}} ([[Karma]], [[rebirth]], [[liberation]] through [[insight]]), but these tenets were so widely held in [[philosophical]] circles of those times that we can no longer regard the {{Wiki|Upanishads}} are the direct source from which the [[Buddha]] has drawn. The special [[metaphysical]] [[concern]] of the {{Wiki|Upanishads}}, the identity of the {{Wiki|individual}} and the [[universal]] [[Atman]], has been mentioned and rejected only in a few passages in the early [[Buddhist texts]], for instance in the saying of the [[Buddha]] quoted earlier. [[Nothing]] shows better the great distance that separates the {{Wiki|Vedanta}} and the teachings of the [[Buddha]], than the fact that the two principal concepts of {{Wiki|Upanishadic}} [[wisdom]], [[Atman]] and [[Brahman]], do not appear anywhere in the [[Buddhist texts]], with the clear and distinct meaning of a "[[primordial]] ground of the [[world]], core of [[existence]], ens realissimum (true [[substance]])," or similarly. As this holds likewise true for the early Jaina {{Wiki|literature}}, one must assume that early {{Wiki|Vedanta}} was of no great importance in [[Magadha]], at the [[time]] of the [[Buddha]] and the Mahavira; otherwise the opposition against if would have left more distinct traces in the texts of these two [[doctrines]]. | + | The number of passages in the [[Pali Canon]] dealing with {{Wiki|Upanishadic}} [[doctrines]], is very small. It is true that [[early Buddhism]] shares many [[doctrines]] with the {{Wiki|Upanishads}} ([[Karma]], [[rebirth]], [[liberation]] through [[insight]]), but these [[tenets]] were so widely held in [[philosophical]] circles of those times that we can no longer regard the {{Wiki|Upanishads}} are the direct source from which the [[Buddha]] has drawn. The special [[metaphysical]] [[concern]] of the {{Wiki|Upanishads}}, the [[Wikipedia:Identity (social science)|identity]] of the {{Wiki|individual}} and the [[universal]] [[Atman]], has been mentioned and rejected only in a few passages in the early [[Buddhist texts]], for instance in the saying of the [[Buddha]] quoted earlier. [[Nothing]] shows better the great distance that separates the {{Wiki|Vedanta}} and the teachings of the [[Buddha]], than the fact that the two [[principal]] [[Wikipedia:concept|concepts]] of {{Wiki|Upanishadic}} [[wisdom]], [[Atman]] and [[Brahman]], do not appear anywhere in the [[Buddhist texts]], with the clear and {{Wiki|distinct}} meaning of a "[[primordial]] ground of the [[world]], core of [[existence]], ens realissimum (true [[substance]])," or similarly. As this holds likewise true for the early [[Jaina]] {{Wiki|literature}}, one must assume that early {{Wiki|Vedanta}} was of no great importance in [[Magadha]], at the [[time]] of the [[Buddha]] and the [[Wikipedia:Mahāvīra|Mahavira]]; otherwise the [[opposition]] against if would have left more {{Wiki|distinct}} traces in the texts of these two [[doctrines]]. |

| − | (2) It is of decisive importance for examining the relation between {{Wiki|Vedanta}} and [[Buddhism]], clearly to establish the meaning of the words [[atta]] and [[anatta]] in [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|literature}}. | + | (2) It is of decisive importance for examining the [[relation]] between {{Wiki|Vedanta}} and [[Buddhism]], clearly to establish the meaning of the words [[atta]] and [[anatta]] in [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|literature}}. |

| − | The meaning of the word attan (nominative: [[atta]], [[Sanskrit]]: [[atman]], nominative: atma) divides into two groups: (1) in daily usage, attan ("[[self]]") serves for denoting one's own [[person]], and has the [[function]] of a reflexive pronoun. This usage is, for instance, illustrated in the 12th Chapter of the [[Dhammapada]]. As a [[philosophical]] term attan denotes the {{Wiki|individual}} [[soul]] as assumed by the Jainas and other schools, but rejected by the [[Buddhists]]. This {{Wiki|individual}} [[soul]] was held to be an [[eternal]] unchangeable [[spiritual]] monad, perfect and blissful by nature, although its qualities may be temporarily obscured through its connection with matter. Starting from this [[view]] held by the heretics, the [[Buddhists]] further understand by the term "[[self]]" ([[atman]]) any [[eternal]], unchangeable {{Wiki|individual}} entity, in other words, that which Western [[metaphysics]] calls a "[[substance]]": "something [[existing]] through and in itself, and not through something else; nor [[existing]] attached to, or inherent in, something else." In the [[philosophical]] usage of the [[Buddhists]], attan is, therefore, any entity of which the heretics wrongly assume that it [[exists]] independently of everything else, and that it has [[existence]] on its own strength. | + | The meaning of the [[word]] [[attan]] ({{Wiki|nominative}}: [[atta]], [[Sanskrit]]: [[atman]], {{Wiki|nominative}}: [[atma]]) divides into two groups: (1) in daily usage, [[attan]] ("[[self]]") serves for denoting one's [[own]] [[person]], and has the [[function]] of a reflexive {{Wiki|pronoun}}. This usage is, for instance, [[illustrated]] in the 12th [[Chapter]] of the [[Dhammapada]]. As a [[philosophical]] term [[attan]] denotes the {{Wiki|individual}} [[soul]] as assumed by the [[Jainas]] and other schools, but rejected by the [[Buddhists]]. This {{Wiki|individual}} [[soul]] was held to be an [[eternal]] unchangeable [[spiritual]] monad, {{Wiki|perfect}} and blissful by [[nature]], although its qualities may be temporarily obscured through its connection with {{Wiki|matter}}. Starting from this [[view]] held by the {{Wiki|heretics}}, the [[Buddhists]] further understand by the term "[[self]]" ([[atman]]) any [[eternal]], unchangeable {{Wiki|individual}} [[entity]], in other words, that which {{Wiki|Western}} [[metaphysics]] calls a "[[substance]]": "something [[existing]] through and in itself, and not through something else; nor [[existing]] [[attached]] to, or [[inherent]] in, something else." In the [[philosophical]] usage of the [[Buddhists]], [[attan]] is, therefore, any [[entity]] of which the {{Wiki|heretics}} wrongly assume that it [[exists]] {{Wiki|independently}} of everything else, and that it has [[existence]] on its [[own]] strength. |

[[File:Aracharya.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Aracharya.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The word anattan (nominative: [[anatta]]) is a noun ([[Sanskrit]]: anatma) and means "[[not-self]]" in the [[sense]] of an entity that is not independent. The word [[anatman]] is found in its meaning of "what is not the [[Soul]] (or [[Spirit]])," also in brahmanical [[Sanskrit]] sources (Bhagavadgita, 6,6; Shankara to [[Brahma]] [[Sutra]] I, 1, 1, Bibl, Indica, p 16; Vedantasara Section 158). Its frequent use in [[Buddhism]] is accounted for by the [[Buddhist]]' [[characteristic]] preference for negative nouns. Phrases like rupam [[anatta]] are therefore to be translated "corporeality is a [[not-self]]," or "corporeality is not an independent entity." | + | The [[word]] anattan ({{Wiki|nominative}}: [[anatta]]) is a {{Wiki|noun}} ([[Sanskrit]]: [[anatma]]) and means "[[not-self]]" in the [[sense]] of an [[entity]] that is not {{Wiki|independent}}. The [[word]] [[anatman]] is found in its meaning of "what is not the [[Soul]] (or [[Spirit]])," also in [[brahmanical]] [[Sanskrit]] sources ({{Wiki|Bhagavadgita}}, 6,6; [[Wikipedia:Adi Shankara|Shankara]] to [[Brahma]] [[Sutra]] I, 1, 1, Bibl, Indica, p 16; Vedantasara Section 158). Its frequent use in [[Buddhism]] is accounted for by the [[Buddhist]]' [[characteristic]] preference for negative nouns. Phrases like rupam [[anatta]] are therefore to be translated "corporeality is a [[not-self]]," or "corporeality is not an {{Wiki|independent}} [[entity]]." |

| − | As an adjective, the word anattan (as occasionally attan too; see [[Dhammapada]] 379; Geiger, [[Pali]] Lit., Section 92) changes from the consonantal to the a-declension; [[anatta]] (see [[Sanskrit]] anatmaka, anatmya), e.g., [[Samyutta]] 22, 55, 7 PTS III p. 56), anattam rupam... anatte sankare... na pajanati ("he does not [[know]] that corporeality is without [[self]],... that the [[mental formations]] are without [[self]]"). The word [[anatta]] is therefore, to be translated here by "not [[having the nature of]] a [[self]], non-independent, without a (persisting) [[self]], without an ([[eternal]]) [[substance]]," etc. The passage anattam rupam [[anatta]] rupan ti yathabhutam na pajanati has to be rendered: "With regard to corporeality having not the nature of a [[self]], he does not [[know]] according to [[truth]], 'Corporeality is a [[not-self]] (not an independent entity).'" The noun attan and the adjective [[anatta]] can both be rendered by "without a [[self]], without an independent [[essence]], without a persisting core," since the [[Buddhists]] themselves do not make any [[difference]] in the use of these two grammatical forms. This becomes particularly evident in the case of the word [[anatta]], which may be either a singular or a plural noun. In the well-known phrase [[sabbe sankhara anicca]]... sabbe [[dhamma]] [[anatta]] (Dhp. 279), "all [[conditioned]] factors of [[existence]] are transitory... all factors [[existent]] whatever ([[Nirvana]] included) are without a [[self]]," it is undoubtedly a plural noun, for the [[Sanskrit]] version has sarve [[dharma]] anatmanah. | + | As an {{Wiki|adjective}}, the [[word]] anattan (as occasionally [[attan]] too; see [[Dhammapada]] 379; Geiger, [[Pali]] [[Lit]]., Section 92) changes from the consonantal to the a-declension; [[anatta]] (see [[Sanskrit]] [[anatmaka]], anatmya), e.g., [[Samyutta]] 22, 55, 7 PTS III p. 56), anattam rupam... anatte sankare... na [[pajanati]] ("he does not [[know]] that corporeality is without [[self]],... that the [[mental formations]] are without [[self]]"). The [[word]] [[anatta]] is therefore, to be translated here by "not [[having the nature of]] a [[self]], non-independent, without a (persisting) [[self]], without an ([[eternal]]) [[substance]]," etc. The passage anattam rupam [[anatta]] rupan ti yathabhutam na [[pajanati]] has to be rendered: "With regard to corporeality having not the [[nature]] of a [[self]], he does not [[know]] according to [[truth]], 'Corporeality is a [[not-self]] (not an {{Wiki|independent}} [[entity]]).'" The {{Wiki|noun}} [[attan]] and the {{Wiki|adjective}} [[anatta]] can both be rendered by "without a [[self]], without an {{Wiki|independent}} [[essence]], without a persisting core," since the [[Buddhists]] themselves do not make any [[difference]] in the use of these two {{Wiki|grammatical}} [[forms]]. This becomes particularly evident in the case of the [[word]] [[anatta]], which may be either a singular or a plural {{Wiki|noun}}. In the well-known [[phrase]] [[sabbe sankhara anicca]]... sabbe [[dhamma]] [[anatta]] (Dhp. 279), "all [[conditioned]] factors of [[existence]] are transitory... all factors [[existent]] whatever ([[Nirvana]] included) are without a [[self]]," it is undoubtedly a plural {{Wiki|noun}}, for the [[Sanskrit]] version has sarve [[dharma]] anatmanah. |

| − | The fact that the [[Anatta]] [[doctrine]] only purports to state that a [[dharma]] is "[[void]] of a [[self]]," is evident from the passage in the [[Samyutta Nikaya]] (35, 85; PTS IV, p.54) where it is said rupa [[sunna]] attena va attaniyenava, "forms are [[void]] of a [[self]] (an independent [[essence]]) and of anything pertaining to a [[self]] (or 'self-like')." | + | The fact that the [[Anatta]] [[doctrine]] only purports to [[state]] that a [[dharma]] is "[[void]] of a [[self]]," is evident from the passage in the [[Samyutta Nikaya]] (35, 85; PTS IV, p.54) where it is said [[rupa]] [[sunna]] attena va attaniyenava, "[[forms]] are [[void]] of a [[self]] (an {{Wiki|independent}} [[essence]]) and of anything pertaining to a [[self]] (or 'self-like')." |

| − | Where Guenther has translated anattan or [[anatta]] as "not the [[self]]," one should use "a [[self]]" instead of "the [[self]]," because in the [[Pali Canon]] the word [[atman]] does not occur in the [[sense]] of "[[universal]] [[soul]]." | + | Where Guenther has translated anattan or [[anatta]] as "not the [[self]]," one should use "a [[self]]" instead of "the [[self]]," because in the [[Pali Canon]] the [[word]] [[atman]] does not occur in the [[sense]] of "[[universal]] [[soul]]." |

| − | (3) It is not necessary to assume that the [[existence]] of indestructible monads is a necessary [[condition]] for a [[belief]] in [[life]] after [[death]]. The [[view]] that an [[eternal]], [[immortal]], persisting [[soul]] [[substance]] is the conditio sine qua non of [[rebirth]] can be refuted by the mere fact that not only in the older {{Wiki|Upanishads}}, but also in {{Wiki|Pythagoras}} and {{Wiki|Empedocles}}, [[rebirth]] is taught without the assumption of an imperishable [[soul]] [[substance]]. | + | (3) It is not necessary to assume that the [[existence]] of [[indestructible]] [[monads]] is a necessary [[condition]] for a [[belief]] in [[life]] after [[death]]. The [[view]] that an [[eternal]], [[immortal]], persisting [[soul]] [[substance]] is the conditio sine qua non of [[rebirth]] can be refuted by the mere fact that not only in the older {{Wiki|Upanishads}}, but also in {{Wiki|Pythagoras}} and {{Wiki|Empedocles}}, [[rebirth]] is [[taught]] without the assumption of an imperishable [[soul]] [[substance]]. |

[[File:A Mandana.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:A Mandana.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | (4) Guenther can substantiate his [[view]] only through arbitrary translations which contradict the whole of [[Buddhist tradition]]. This is particularly evident in those passages where Guenther asserts that "the [[Buddha]] meant the same by [[Nirvana]] and [[atman]]" and that "[[Nirvana]] is the [[true nature]] of man." For in [[Udana]] 8,2, [[Nirvana]] is expressly described as anattam, which is rightly rendered by Dhammapala's commentary (p. 21) as atta-virahita (without a [[self]]), and in [[Vinaya]] V, p. 86, [[Nirvana]] is said to be, just as the [[conditioned]] factors of [[existence]] (sankhata), "without a [[self]]" (p. 151). Neither can the equation atman=nirvana be proved by the well-known phrase attadipa viharatha, dhammadipa, for, whether [[dipa]] here means "[[lamp]]" or "island of [[deliverance]]," this passage can, after all, only refer to the [[monks]] taking [[refuge]] in themselves and in the [[doctrine]] (dhamma),and attan and [[dhamma]] cannot possibly be interpreted as [[Nirvana]]. In the same way, too, it is quite preposterous to translate [[Dhammapada]] 160, [[atta]] hi attano natho as "[[Nirvana]] is for a man the leader" (p. 155); for the chapter is concerned only with the [[idea]] that we should strive hard and purify ourselves. Otherwise Guenther would have to translate in the following verse 161, attana va katam papam attajam attasambhavam: "By [[Nirvana]] [[evil]] is done, it arises out of [[Nirvana]], it has its origin in [[Nirvana]]." It is obvious that this kind of interpretation must lead to manifestly absurd consequences. | + | (4) Guenther can substantiate his [[view]] only through arbitrary translations which contradict the whole of [[Buddhist tradition]]. This is particularly evident in those passages where Guenther asserts that "the [[Buddha]] meant the same by [[Nirvana]] and [[atman]]" and that "[[Nirvana]] is the [[true nature]] of man." For in [[Udana]] 8,2, [[Nirvana]] is expressly described as anattam, which is rightly rendered by [[Dhammapala's]] commentary (p. 21) as atta-virahita (without a [[self]]), and in [[Vinaya]] V, p. 86, [[Nirvana]] is said to be, just as the [[conditioned]] factors of [[existence]] ([[sankhata]]), "without a [[self]]" (p. 151). Neither can the equation atman=nirvana be proved by the well-known [[phrase]] [[attadipa]] viharatha, dhammadipa, for, whether [[dipa]] here means "[[lamp]]" or "[[island]] of [[deliverance]]," this passage can, after all, only refer to the [[monks]] taking [[refuge]] in themselves and in the [[doctrine]] (dhamma),and [[attan]] and [[dhamma]] cannot possibly be interpreted as [[Nirvana]]. In the same way, too, it is quite preposterous to translate [[Dhammapada]] 160, [[atta]] hi attano natho as "[[Nirvana]] is for a man the leader" (p. 155); for the [[chapter]] is concerned only with the [[idea]] that we should strive hard and {{Wiki|purify}} ourselves. Otherwise Guenther would have to translate in the following verse 161, attana va katam papam attajam attasambhavam: "By [[Nirvana]] [[evil]] is done, it arises out of [[Nirvana]], it has its origin in [[Nirvana]]." It is obvious that this kind of interpretation must lead to manifestly absurd {{Wiki|consequences}}. |

| − | (5) As far as I can see there is not a single passage in the [[Pali Canon]] where the word [[atta]] is used in the [[sense]] of the {{Wiki|Upanishadic}} Atman.1 This is not surprising, since the word [[atman]], current in all [[Indian]] [[philosophical]] systems, has the meaning of "[[universal]] [[soul]], ens realissimum, the [[Absolute]]," exclusively in the pan-en-theistic and theopantistic {{Wiki|Vedanta}}, but, in that [[sense]], it is alien to all other brahmanical and non-Buddhist [[doctrines]]. Why, then, should it have a {{Wiki|Vedantic}} meaning in [[Buddhism]]? As far as I [[know]], no one has ever conceived the [[idea]] of giving to the term [[atman]] a {{Wiki|Vedantic}} interpretation, in the case of [[Nyaya]], {{Wiki|Vaisesika}}, classical Sankhya, [[Yoga]], Mimamsa, or [[Jainism]]. | + | (5) As far as I can see there is not a single passage in the [[Pali Canon]] where the [[word]] [[atta]] is used in the [[sense]] of the {{Wiki|Upanishadic}} Atman.1 This is not surprising, since the [[word]] [[atman]], current in all [[Indian]] [[philosophical]] systems, has the meaning of "[[universal]] [[soul]], ens realissimum, the [[Absolute]]," exclusively in the pan-en-theistic and theopantistic {{Wiki|Vedanta}}, but, in that [[sense]], it is alien to all other [[brahmanical]] and [[non-Buddhist]] [[doctrines]]. Why, then, should it have a {{Wiki|Vedantic}} meaning in [[Buddhism]]? As far as I [[know]], no one has ever [[conceived]] the [[idea]] of giving to the term [[atman]] a {{Wiki|Vedantic}} interpretation, in the case of [[Nyaya]], {{Wiki|Vaisesika}}, classical [[Sankhya]], [[Yoga]], [[Mimamsa]], or [[Jainism]]. |

| − | (6) The fact that in the [[Pali Canon]] all [[worldly]] [[phenomena]] are said to be [[anatta]] has induced some [[scholars]] of the West to look for an [[Atman]] in [[Buddhism]]. For instance, the following "great [[syllogism]]" was formulated by George Grimm: "What I perceive to arise and to cease, and to [[cause]] [[suffering]] to me, on account of that [[impermanence]], cannot be my [[ego]]. Now I perceive that everything cognizable in me and around me, arises and ceases, and [[causes]] me [[suffering]] on account of its [[impermanence]]. Therefore [[nothing]] cognizable is my [[ego]]." From that Grimm concludes that there must be an [[eternal]] ego-substance that is free from all [[suffering]], and above all cognizability. This is a rash conclusion. By [[teaching]] that there is nowhere in the [[world]] a persisting [[Atman]], the [[Buddha]] has not asserted that there must be a [[transcendental]] [[Atman]] (i.e., a [[self]] beyond the [[world]]). This kind of [[logic]] resembles that of a certain {{Wiki|Christian}} sect which worships its [[masters]] as "Christs on [[earth]]," and tries to prove the simultaneous [[existence]] of several Christs from Mark 13,22, where it is said: "False Christs and false prophets shall arise"; for, if there are false Christs, there must also be genuine Christs! | + | (6) The fact that in the [[Pali Canon]] all [[worldly]] [[phenomena]] are said to be [[anatta]] has induced some [[scholars]] of the [[West]] to look for an [[Atman]] in [[Buddhism]]. For instance, the following "great [[syllogism]]" was formulated by George Grimm: "What I {{Wiki|perceive}} to arise and to cease, and to [[cause]] [[suffering]] to me, on account of that [[impermanence]], cannot be my [[ego]]. Now I {{Wiki|perceive}} that everything cognizable in me and around me, arises and ceases, and [[causes]] me [[suffering]] on account of its [[impermanence]]. Therefore [[nothing]] cognizable is my [[ego]]." From that Grimm concludes that there must be an [[eternal]] ego-substance that is free from all [[suffering]], and above all cognizability. This is a rash conclusion. By [[teaching]] that there is nowhere in the [[world]] a persisting [[Atman]], the [[Buddha]] has not asserted that there must be a [[transcendental]] [[Atman]] (i.e., a [[self]] beyond the [[world]]). This kind of [[logic]] resembles that of a certain {{Wiki|Christian}} [[sect]] which worships its [[masters]] as "Christs on [[earth]]," and tries to prove the simultaneous [[existence]] of several Christs from Mark 13,22, where it is said: "False Christs and false {{Wiki|prophets}} shall arise"; for, if there are false Christs, there must also be genuine Christs! |

| − | The denial of an imperishable [[Atman]] is common ground for all systems of [[Hinayana]] as well as [[Mahayana]], and there is, therefore, no [[reason]] for the assumption that [[Buddhist tradition]], unanimous on that point, has deviated from the original [[doctrine]] of the [[Buddha]]. If the [[Buddha]], contrary to the [[Buddhist tradition]], had actually proclaimed a [[transcendental]] [[Atman]], a reminiscence of it would have been preserved somehow by one of the older sects. It is remarkable that even the Pudgalavadins, who assume a kind of {{Wiki|individual}} [[soul]], never appeal to texts in which an [[Atman]] in this [[sense]] is proclaimed. He who advocates such a revolutionary conception of the [[Buddha's teachings]], has also the duty to show evidence how such a complete [[transformation]] started and grew, suddenly or gradually. But non of those who advocate the Atta-theory has taken to comply with that demand which is indispensable to a historian. | + | The {{Wiki|denial}} of an imperishable [[Atman]] is common ground for all systems of [[Hinayana]] as well as [[Mahayana]], and there is, therefore, no [[reason]] for the assumption that [[Buddhist tradition]], unanimous on that point, has deviated from the original [[doctrine]] of the [[Buddha]]. If the [[Buddha]], contrary to the [[Buddhist tradition]], had actually proclaimed a [[transcendental]] [[Atman]], a [[reminiscence]] of it would have been preserved somehow by one of the older sects. It is remarkable that even the [[Pudgalavadins]], who assume a kind of {{Wiki|individual}} [[soul]], never appeal to texts in which an [[Atman]] in this [[sense]] is proclaimed. He who advocates such a {{Wiki|revolutionary}} {{Wiki|conception}} of the [[Buddha's teachings]], has also the [[duty]] to show {{Wiki|evidence}} how such a complete [[transformation]] started and grew, suddenly or gradually. But non of those who advocate the Atta-theory has taken to comply with that demand which is indispensable to a historian. |

[[File:Rya 1.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Rya 1.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | (7) In addition to the aforementioned [[reasons]], there are other grounds too, which speak against the supposition that the [[Buddha]] has identified [[Atman]] and [[Nirvana]]. It remains quite incomprehensible why the [[Buddha]] should have used this expression which is quite unsuitable for [[Nirvana]] and would have aroused only wrong associations in his listeners. Though it is true that [[Nirvana]] shares with the {{Wiki|Vedantic}} conception of [[Atman]] the qualification of [[eternal]] [[peace]] into which the liberated ones enter forever, on the other hand, the [[Atman]] is in brahmanical opinion, something [[mental]] and [[conscious]], a description which does not hold true for [[Nirvana]]. Furthermore, [[Nirvana]] is not, like the [[Atman]], the [[primordial]] ground or the [[divine]] principle of the [[world]] (Aitareya Up. 1,1), nor is it that which preserves [[order]] in the [[world]] (Brhadar. Up. 3,8,9); it is also not the [[substance]] from which everything evolves, nor the core of all material [[elements]]. | + | (7) In addition to the aforementioned [[reasons]], there are other grounds too, which speak against the supposition that the [[Buddha]] has identified [[Atman]] and [[Nirvana]]. It remains quite incomprehensible why the [[Buddha]] should have used this expression which is quite unsuitable for [[Nirvana]] and would have aroused only wrong associations in his [[listeners]]. Though it is true that [[Nirvana]] shares with the {{Wiki|Vedantic}} {{Wiki|conception}} of [[Atman]] the qualification of [[eternal]] [[peace]] into which the {{Wiki|liberated}} ones enter forever, on the other hand, the [[Atman]] is in [[brahmanical]] opinion, something [[mental]] and [[conscious]], a description which does not hold true for [[Nirvana]]. Furthermore, [[Nirvana]] is not, like the [[Atman]], the [[primordial]] ground or the [[divine]] [[principle]] of the [[world]] ([[Aitareya]] Up. 1,1), nor is it that which preserves [[order]] in the [[world]] (Brhadar. Up. 3,8,9); it is also not the [[substance]] from which everything evolves, nor the core of all material [[elements]]. |

| − | (8) Since the [[scholarly]] researches made by Otto Rosenberg (published in Russian 1918, in German trs. 1924), Th. Stcherbatsky (1932), and the great work of translation done by Louis de la Vallee Poussin [[Abhidharmakosa]] (1923-31) there cannot be any [[doubt]] about the basic principle of [[Buddhist philosophy]]. In the [[light]] of these researches, all attempts to give to the [[Atman]] a place in the [[Buddhist doctrine]], appear to be quite antiquated. We [[know]] now that all [[Hinayana]] and [[Mahayana]] schools are based on the anatma-dharma {{Wiki|theory}}. This {{Wiki|theory}} explains the [[world]] through the [[causal]] co-operation of a multitude of transitory factors ([[dharma]]), arising in mutual functional dependence. This {{Wiki|theory}} maintains that the entire process of [[liberation]] consists in the tranquilization of these incessantly arising and disappearing factors. For that process of [[liberation]] however, is required, apart from [[moral]] restraint ([[sila]]) and [[meditative]] [[concentration]] ([[samadhi]]), the [[insight]] ([[prajna]]) that all [[conditioned]] factors of [[existence]] ([[samskara]]) are transitory, without a permanent independent [[existence]], and therefore [[subject]] to [[grief]] and [[suffering]]. The [[Nirvana]] which the {{Wiki|saint}} [[experiences]] already in this [[life]], and which he enters for ever after [[death]], is certainly a [[reality]] ([[dharma]]), but as it neither arises nor vanishes, it is not [[subject]] to [[suffering]], and is thereby distinguished from all [[conditioned]] [[realities]]. [[Nirvana]] [[being]] a [[dharma]], is likewise [[anatta]], just as the transitory, [[conditioned]] [[dharmas]] of the [[Samsara]] which, as [[caused]] by [[Wikipedia:Volition (psychology)|volitions]] (that is, karma-producing energies ([[samskara]])), are themselves also called [[samskara]]. Like them, [[Nirvana]] is no {{Wiki|individual}} entity which could act independently. For it is the basic [[idea]] of the entire system that all [[dharmas]] are devoid of [[Atman]], and without cogent [[reasons]] we cannot assume that the [[Buddha]] himself has [[thought]] something different from that which since more than two thousand years, his followers have considered to be the quintessence of their [[doctrine]]. | + | (8) Since the [[scholarly]] researches made by Otto Rosenberg (published in {{Wiki|Russian}} 1918, in {{Wiki|German}} trs. 1924), [[Wikipedia:Fyodor Shcherbatskoy|Th. Stcherbatsky]] (1932), and the great work of translation done by Louis de la Vallee [[Wikipedia:Louis de La Vallée-Poussin|Poussin]] [[Abhidharmakosa]] (1923-31) there cannot be any [[doubt]] about the basic [[principle]] of [[Buddhist philosophy]]. In the [[light]] of these researches, all attempts to give to the [[Atman]] a place in the [[Buddhist doctrine]], appear to be quite antiquated. We [[know]] now that all [[Hinayana]] and [[Mahayana]] schools are based on the anatma-dharma {{Wiki|theory}}. This {{Wiki|theory}} explains the [[world]] through the [[causal]] co-operation of a multitude of transitory factors ([[dharma]]), [[arising]] in mutual functional [[dependence]]. This {{Wiki|theory}} maintains that the entire process of [[liberation]] consists in the tranquilization of these incessantly [[arising]] and disappearing factors. For that process of [[liberation]] however, is required, apart from [[moral]] {{Wiki|restraint}} ([[sila]]) and [[meditative]] [[concentration]] ([[samadhi]]), the [[insight]] ([[prajna]]) that all [[conditioned]] factors of [[existence]] ([[samskara]]) are transitory, without a [[permanent]] {{Wiki|independent}} [[existence]], and therefore [[subject]] to [[grief]] and [[suffering]]. The [[Nirvana]] which the {{Wiki|saint}} [[experiences]] already in this [[life]], and which he enters for ever after [[death]], is certainly a [[reality]] ([[dharma]]), but as it neither arises nor vanishes, it is not [[subject]] to [[suffering]], and is thereby {{Wiki|distinguished}} from all [[conditioned]] [[realities]]. [[Nirvana]] [[being]] a [[dharma]], is likewise [[anatta]], just as the transitory, [[conditioned]] [[dharmas]] of the [[Samsara]] which, as [[caused]] by [[Wikipedia:Volition (psychology)|volitions]] (that is, karma-producing energies ([[samskara]])), are themselves also called [[samskara]]. Like them, [[Nirvana]] is no {{Wiki|individual}} [[entity]] which could act {{Wiki|independently}}. For it is the basic [[idea]] of the entire system that all [[dharmas]] are devoid of [[Atman]], and without cogent [[reasons]] we cannot assume that the [[Buddha]] himself has [[thought]] something different from that which since more than two thousand years, his followers have considered to be the quintessence of their [[doctrine]]. |

Note | Note | ||

| − | 1. Except in a few passages rejecting it, as the one quoted by the author: "The same is the [[world]] and the [[self]]"; see also Sutta-nipata, v 477; and one of the six [[Ego]]- [[beliefs]] rejected in Majjh. 2: "'Even by the [[self]] I perceive the [[self]]': this [[view]] occurs to him as [[being]] true and correct" (attana va attanam sanjanamit'titi). Of Bhagavadgita VI 19 Yatra caiv' atmana atmanam pasyann-atmani tusyati. — The BPS Editor | + | 1. Except in a few passages rejecting it, as the one quoted by the author: "The same is the [[world]] and the [[self]]"; see also [[Sutta-nipata]], v 477; and one of the six [[Ego]]- [[beliefs]] rejected in Majjh. 2: "'Even by the [[self]] I {{Wiki|perceive}} the [[self]]': this [[view]] occurs to him as [[being]] true and correct" (attana va attanam sanjanamit'titi). Of {{Wiki|Bhagavadgita}} VI 19 Yatra caiv' atmana [[atmanam]] pasyann-atmani tusyati. — The BPS Editor |

{{R}} | {{R}} | ||

[http://www.hinduwebsite.com/buddhism/essays/vedantaand_buddhism.asp www.hinduwebsite.com] | [http://www.hinduwebsite.com/buddhism/essays/vedantaand_buddhism.asp www.hinduwebsite.com] | ||

[[Category:Vedanta]] | [[Category:Vedanta]] | ||

Latest revision as of 03:52, 30 January 2015

The present treatise by Prof. Dr. H.V. Glasenapp has been selected for reprint particularly in view of the excellent elucidation of the Anatta Doctrine which it contains. The treatise, in its German original, appeared in 1950 in the Proceeding of the "Akademie der Wissenschaften and Literatur" (Academy of Sciences and Literature). The present selection from that original is based on the abridged translations published in "The Buddhist," Vol.XXI, No. 12 (Colombo 1951). Partial use has also been made of a different selection and translation which appeared in "The Middle Way," Vol. XXXI, No. 4 (London 1957).

The author of this treatise is an eminent Indologist of Western Germany, formerly of the University of Koenigsberg, now occupying the indological chair of the University of Tuebingen. Among his many scholarly publications are books on Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism and on comparative religion.

— Buddhist Publication Society Vedanta and Buddhism

Vedanta and Buddhism are the highlights of Indian philosophical thought. Since both have grown in the same spiritual soil, they share many basic ideas: both of them assert that the universe shows a periodical succession of arising, existing and vanishing, and that this process is without beginning and end. They believe in the causality which binds the result of an action to its cause (karma), and in rebirth conditioned by that nexus. Both are convinced of the transitory, and therefore sorrowful character, of individual existence in the world; they hope to attain gradually to a redeeming knowledge through renunciation and meditation and they assume the possibility of a blissful and serene state, in which all worldly imperfections have vanished for ever. The original form of these two doctrines shows however strong contrast. The early Vedanta, formulated in most of the older and middle Upanishads, in some passages of the Mahabharata and the Puranas, and still alive today (though greatly changed) as the basis of several Hinduistic systems, teaches an ens realissimum (an entity of highest reality) as the primordial cause of all existence, from which everything has arisen and with which it again merges, either temporarily or for ever.

With the monistic metaphysics of the Vedanta contrasts the pluralistic Philosophy of Flux of the early Buddhism of the Pali texts which up to the present time flourishes in Ceylon, Burma and Siam. It teaches that in the whole empirical reality there is nowhere anything that persists; neither material nor mental substances exist independently by themselves; there is no original entity or primordial Being in whatsoever form it may be imagined, from which these substances might have developed. On the contrary, the manifold world of mental and material elements arises solely through the causal co-operation of the transitory factors of existence (dharma) which depend functionally upon each other, that is, the material and mental universe arises through the concurrence of forces that, according to the Buddhists, are not reducible to something else. It is therefore obvious that deliverance from the Samsara, i.e., the sorrow-laden round of existence, cannot consist in the re-absorption into an eternal Absolute which is at the root of all manifoldness, but can only be achieved by a complete extinguishing of all factors which condition the processes constituting life and world. The Buddhist Nirvana is, therefore, not the primordial ground, the eternal essence, which is at the basis of everything and form which the whole world has arisen (the Brahman of the Upanishads) but the reverse of all that we know, something altogether different which must be characterized as a nothing in relation to the world, but which is experienced as highest bliss by those who have attained to it (Anguttara Nikaya, Navaka-nipata 34). Vedantists and Buddhists have been fully aware of the gulf between their doctrines, a gulf that cannot be bridged over. According to Majjhima Nikaya, Sutta 22, a doctrine that proclaims "The same is the world and the self. This I shall be after death; imperishable, permanent, eternal!" (see Brh. UP. 4, 4, 13), was styled by the Buddha a perfectly foolish doctrine. On the other side, the Katha-Upanishad (2, 1, 14) does not see a way to deliverance in the Buddhist theory of dharmas (impersonal processes): He who supposes a profusion of particulars gets lost like rain water on a mountain slope; the truly wise man, however, must realize that his Atman is at one with the Universal Atman, and that the former, if purified from dross, is being absorbed by the latter, "just as clear water poured into clear water becomes one with it, indistinguishably."

Vedanta and Buddhism have lived side by side for such a long time that obviously they must have influenced each other. The strong predilection of the Indian mind for a doctrine of universal unity (monism) has led the representatives of Mahayana to conceive Samsara and Nirvana as two aspects of the same and single true reality; for Nagarjuna the empirical world is a mere appearance, as all dharmas, manifest in it, are perishable and conditioned by other dharmas, without having any independent existence of their own. Only the indefinable "Voidness" (sunyata) to be grasped in meditation, and realized in Nirvana, has true reality.

This so-called Middle Doctrine of Nagarjuna remains true to the Buddhist principle that there can be nowhere a substance, in so far as Nagarjuna sees the last unity as a kind of abyss, characterized only negatively, which has no genetic relation to the world. Asanga and Vasubandhu, however, in their doctrine of Consciousness Only, have abandoned the Buddhist principle of denying a positive reality which is at the root all phenomena, and in doing so, they have made a further approach to Vedanta. To that mahayanistic school of Yogacaras, the highest reality is a pure and undifferentiated spiritual element that represents the non- relative substratum of all phenomena. To be sure, they thereby do not assert, as the (older) Vedanta does, that the ens realissimum (the highest essence) is identical with the universe, the relation between the two is rather being defined as "being neither different nor not different." It is only in the later Buddhist systems of the Far East that the undivided, absolute consciousness is taken to be the basis of the manifold world of phenomena. But in contrast to the older Vedanta, it is never maintained that the world is an unfoldment from the unchangeable, eternal, blissful Absolute; suffering and passions, manifest in the world of plurality, are rather traced back to worldly delusion.

On the other hand, the doctrines of later Buddhist philosophy had a far-reaching influence on Vedanta. It is well known that Gaudapada, and other representatives of later Vedanta, taught an illusionistic acosmism, for which true Reality is only "the eternally pure, eternally awakened, eternally redeemed" universal spirit whilst all manifoldness is only delusion; the Brahma has therefore not developed into the world, as asserted by the older Vedanta, but it forms only the world's unchangeable background, comparable to the white screen on which appear the changing images of an unreal shadow play.

In my opinion, there was in later times, especially since the Christian era, much mutual influence of Vedanta and Buddhism, but originally the systems are diametrically opposed to each other. The Atman doctrine of the Vedanta and the Dharma theory of Buddhism exclude each other. The Vedanta tries to establish an Atman as the basis of everything, whilst Buddhism maintains that everything in the empirical world is only a stream of passing Dharmas (impersonal and evanescent processes) which therefore has to be characterized as Anatta, i.e., being without a persisting self, without independent existence.

Again and again scholars have tried to prove a closer connection between the early Buddhism of the Pali texts, and the Vedanta of the Upanishads; they have even tried to interpret Buddhism as a further development of the Atman doctrine. There are, e.g., two books which show that tendency: The Vedantic Buddhism of the Buddha, by J.G. Jennings (Oxford University Press, 1947), and in German language, The Soul Problem of Early Buddhism, by Herbert Guenther (Konstanz 1949).

The essential difference between the conception of deliverance in Vedanta and in Pali Buddhism lies in the following ideas: Vedanta sees deliverance as the manifestation of a state which, though obscured, has been existing from time immemorial; for the Buddhist, however, Nirvana is a reality which differs entirely from all dharmas as manifested in Samsara, and which only becomes effective, if they are abolished. To sum up: the Vedantin wishes to penetrate to the last reality which dwells within him as an immortal essence, or seed, out of which everything has arisen. The follower of Pali Buddhism, however, hopes by complete abandoning of all corporeality, all sensations, all perceptions, all volitions, and acts of consciousness, to realize a state of bliss which is entirely different from all that exists in the Samsara.

After these introductory remarks we shall now discuss systematically the relation of original Buddhism and Vedanta.

(1) First of all we have to clarify to what extent a knowledge of Upanishadic texts may be assumed for the canonical Pali scriptures. The five old prose Upanishads are, on reasons of contents and language, generally held to be pre-Buddhistic. The younger Upanishads, in any case those beginning from Maitrayana, were certainly written at a time when Buddhism already existed.

The number of passages in the Pali Canon dealing with Upanishadic doctrines, is very small. It is true that early Buddhism shares many doctrines with the Upanishads (Karma, rebirth, liberation through insight), but these tenets were so widely held in philosophical circles of those times that we can no longer regard the Upanishads are the direct source from which the Buddha has drawn. The special metaphysical concern of the Upanishads, the identity of the individual and the universal Atman, has been mentioned and rejected only in a few passages in the early Buddhist texts, for instance in the saying of the Buddha quoted earlier. Nothing shows better the great distance that separates the Vedanta and the teachings of the Buddha, than the fact that the two principal concepts of Upanishadic wisdom, Atman and Brahman, do not appear anywhere in the Buddhist texts, with the clear and distinct meaning of a "primordial ground of the world, core of existence, ens realissimum (true substance)," or similarly. As this holds likewise true for the early Jaina literature, one must assume that early Vedanta was of no great importance in Magadha, at the time of the Buddha and the Mahavira; otherwise the opposition against if would have left more distinct traces in the texts of these two doctrines.

(2) It is of decisive importance for examining the relation between Vedanta and Buddhism, clearly to establish the meaning of the words atta and anatta in Buddhist literature.

The meaning of the word attan (nominative: atta, Sanskrit: atman, nominative: atma) divides into two groups: (1) in daily usage, attan ("self") serves for denoting one's own person, and has the function of a reflexive pronoun. This usage is, for instance, illustrated in the 12th Chapter of the Dhammapada. As a philosophical term attan denotes the individual soul as assumed by the Jainas and other schools, but rejected by the Buddhists. This individual soul was held to be an eternal unchangeable spiritual monad, perfect and blissful by nature, although its qualities may be temporarily obscured through its connection with matter. Starting from this view held by the heretics, the Buddhists further understand by the term "self" (atman) any eternal, unchangeable individual entity, in other words, that which Western metaphysics calls a "substance": "something existing through and in itself, and not through something else; nor existing attached to, or inherent in, something else." In the philosophical usage of the Buddhists, attan is, therefore, any entity of which the heretics wrongly assume that it exists independently of everything else, and that it has existence on its own strength.

The word anattan (nominative: anatta) is a noun (Sanskrit: anatma) and means "not-self" in the sense of an entity that is not independent. The word anatman is found in its meaning of "what is not the Soul (or Spirit)," also in brahmanical Sanskrit sources (Bhagavadgita, 6,6; Shankara to Brahma Sutra I, 1, 1, Bibl, Indica, p 16; Vedantasara Section 158). Its frequent use in Buddhism is accounted for by the Buddhist' characteristic preference for negative nouns. Phrases like rupam anatta are therefore to be translated "corporeality is a not-self," or "corporeality is not an independent entity."

As an adjective, the word anattan (as occasionally attan too; see Dhammapada 379; Geiger, Pali Lit., Section 92) changes from the consonantal to the a-declension; anatta (see Sanskrit anatmaka, anatmya), e.g., Samyutta 22, 55, 7 PTS III p. 56), anattam rupam... anatte sankare... na pajanati ("he does not know that corporeality is without self,... that the mental formations are without self"). The word anatta is therefore, to be translated here by "not having the nature of a self, non-independent, without a (persisting) self, without an (eternal) substance," etc. The passage anattam rupam anatta rupan ti yathabhutam na pajanati has to be rendered: "With regard to corporeality having not the nature of a self, he does not know according to truth, 'Corporeality is a not-self (not an independent entity).'" The noun attan and the adjective anatta can both be rendered by "without a self, without an independent essence, without a persisting core," since the Buddhists themselves do not make any difference in the use of these two grammatical forms. This becomes particularly evident in the case of the word anatta, which may be either a singular or a plural noun. In the well-known phrase sabbe sankhara anicca... sabbe dhamma anatta (Dhp. 279), "all conditioned factors of existence are transitory... all factors existent whatever (Nirvana included) are without a self," it is undoubtedly a plural noun, for the Sanskrit version has sarve dharma anatmanah.

The fact that the Anatta doctrine only purports to state that a dharma is "void of a self," is evident from the passage in the Samyutta Nikaya (35, 85; PTS IV, p.54) where it is said rupa sunna attena va attaniyenava, "forms are void of a self (an independent essence) and of anything pertaining to a self (or 'self-like')."

Where Guenther has translated anattan or anatta as "not the self," one should use "a self" instead of "the self," because in the Pali Canon the word atman does not occur in the sense of "universal soul."

(3) It is not necessary to assume that the existence of indestructible monads is a necessary condition for a belief in life after death. The view that an eternal, immortal, persisting soul substance is the conditio sine qua non of rebirth can be refuted by the mere fact that not only in the older Upanishads, but also in Pythagoras and Empedocles, rebirth is taught without the assumption of an imperishable soul substance.

(4) Guenther can substantiate his view only through arbitrary translations which contradict the whole of Buddhist tradition. This is particularly evident in those passages where Guenther asserts that "the Buddha meant the same by Nirvana and atman" and that "Nirvana is the true nature of man." For in Udana 8,2, Nirvana is expressly described as anattam, which is rightly rendered by Dhammapala's commentary (p. 21) as atta-virahita (without a self), and in Vinaya V, p. 86, Nirvana is said to be, just as the conditioned factors of existence (sankhata), "without a self" (p. 151). Neither can the equation atman=nirvana be proved by the well-known phrase attadipa viharatha, dhammadipa, for, whether dipa here means "lamp" or "island of deliverance," this passage can, after all, only refer to the monks taking refuge in themselves and in the doctrine (dhamma),and attan and dhamma cannot possibly be interpreted as Nirvana. In the same way, too, it is quite preposterous to translate Dhammapada 160, atta hi attano natho as "Nirvana is for a man the leader" (p. 155); for the chapter is concerned only with the idea that we should strive hard and purify ourselves. Otherwise Guenther would have to translate in the following verse 161, attana va katam papam attajam attasambhavam: "By Nirvana evil is done, it arises out of Nirvana, it has its origin in Nirvana." It is obvious that this kind of interpretation must lead to manifestly absurd consequences.

(5) As far as I can see there is not a single passage in the Pali Canon where the word atta is used in the sense of the Upanishadic Atman.1 This is not surprising, since the word atman, current in all Indian philosophical systems, has the meaning of "universal soul, ens realissimum, the Absolute," exclusively in the pan-en-theistic and theopantistic Vedanta, but, in that sense, it is alien to all other brahmanical and non-Buddhist doctrines. Why, then, should it have a Vedantic meaning in Buddhism? As far as I know, no one has ever conceived the idea of giving to the term atman a Vedantic interpretation, in the case of Nyaya, Vaisesika, classical Sankhya, Yoga, Mimamsa, or Jainism.

(6) The fact that in the Pali Canon all worldly phenomena are said to be anatta has induced some scholars of the West to look for an Atman in Buddhism. For instance, the following "great syllogism" was formulated by George Grimm: "What I perceive to arise and to cease, and to cause suffering to me, on account of that impermanence, cannot be my ego. Now I perceive that everything cognizable in me and around me, arises and ceases, and causes me suffering on account of its impermanence. Therefore nothing cognizable is my ego." From that Grimm concludes that there must be an eternal ego-substance that is free from all suffering, and above all cognizability. This is a rash conclusion. By teaching that there is nowhere in the world a persisting Atman, the Buddha has not asserted that there must be a transcendental Atman (i.e., a self beyond the world). This kind of logic resembles that of a certain Christian sect which worships its masters as "Christs on earth," and tries to prove the simultaneous existence of several Christs from Mark 13,22, where it is said: "False Christs and false prophets shall arise"; for, if there are false Christs, there must also be genuine Christs!

The denial of an imperishable Atman is common ground for all systems of Hinayana as well as Mahayana, and there is, therefore, no reason for the assumption that Buddhist tradition, unanimous on that point, has deviated from the original doctrine of the Buddha. If the Buddha, contrary to the Buddhist tradition, had actually proclaimed a transcendental Atman, a reminiscence of it would have been preserved somehow by one of the older sects. It is remarkable that even the Pudgalavadins, who assume a kind of individual soul, never appeal to texts in which an Atman in this sense is proclaimed. He who advocates such a revolutionary conception of the Buddha's teachings, has also the duty to show evidence how such a complete transformation started and grew, suddenly or gradually. But non of those who advocate the Atta-theory has taken to comply with that demand which is indispensable to a historian.

(7) In addition to the aforementioned reasons, there are other grounds too, which speak against the supposition that the Buddha has identified Atman and Nirvana. It remains quite incomprehensible why the Buddha should have used this expression which is quite unsuitable for Nirvana and would have aroused only wrong associations in his listeners. Though it is true that Nirvana shares with the Vedantic conception of Atman the qualification of eternal peace into which the liberated ones enter forever, on the other hand, the Atman is in brahmanical opinion, something mental and conscious, a description which does not hold true for Nirvana. Furthermore, Nirvana is not, like the Atman, the primordial ground or the divine principle of the world (Aitareya Up. 1,1), nor is it that which preserves order in the world (Brhadar. Up. 3,8,9); it is also not the substance from which everything evolves, nor the core of all material elements.

(8) Since the scholarly researches made by Otto Rosenberg (published in Russian 1918, in German trs. 1924), Th. Stcherbatsky (1932), and the great work of translation done by Louis de la Vallee Poussin Abhidharmakosa (1923-31) there cannot be any doubt about the basic principle of Buddhist philosophy. In the light of these researches, all attempts to give to the Atman a place in the Buddhist doctrine, appear to be quite antiquated. We know now that all Hinayana and Mahayana schools are based on the anatma-dharma theory. This theory explains the world through the causal co-operation of a multitude of transitory factors (dharma), arising in mutual functional dependence. This theory maintains that the entire process of liberation consists in the tranquilization of these incessantly arising and disappearing factors. For that process of liberation however, is required, apart from moral restraint (sila) and meditative concentration (samadhi), the insight (prajna) that all conditioned factors of existence (samskara) are transitory, without a permanent independent existence, and therefore subject to grief and suffering. The Nirvana which the saint experiences already in this life, and which he enters for ever after death, is certainly a reality (dharma), but as it neither arises nor vanishes, it is not subject to suffering, and is thereby distinguished from all conditioned realities. Nirvana being a dharma, is likewise anatta, just as the transitory, conditioned dharmas of the Samsara which, as caused by volitions (that is, karma-producing energies (samskara)), are themselves also called samskara. Like them, Nirvana is no individual entity which could act independently. For it is the basic idea of the entire system that all dharmas are devoid of Atman, and without cogent reasons we cannot assume that the Buddha himself has thought something different from that which since more than two thousand years, his followers have considered to be the quintessence of their doctrine.

Note

1. Except in a few passages rejecting it, as the one quoted by the author: "The same is the world and the self"; see also Sutta-nipata, v 477; and one of the six Ego- beliefs rejected in Majjh. 2: "'Even by the self I perceive the self': this view occurs to him as being true and correct" (attana va attanam sanjanamit'titi). Of Bhagavadgita VI 19 Yatra caiv' atmana atmanam pasyann-atmani tusyati. — The BPS Editor