Difference between revisions of "Tibetan Buddhism"

m (Text replacement - "Dharamsala" to "{{Wiki|Dharamsala}}") |

m (Text replacement - "Ladakh" to "{{Wiki|Ladakh}}") |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:BMR.86.1.23.3-O-1-.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:BMR.86.1.23.3-O-1-.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [[Tibetan Buddhism]] is the [[body]] of [[Buddhist]] [[religious]] [[doctrine]] and {{Wiki|institutions}} [[characteristic]] of [[Tibet]] and certain regions of the [[Himalayas]], including northern [[Nepal]], [[Bhutan]], and [[India]] (particularly in {{Wiki|Arunachal Pradesh}}, | + | [[Tibetan Buddhism]] is the [[body]] of [[Buddhist]] [[religious]] [[doctrine]] and {{Wiki|institutions}} [[characteristic]] of [[Tibet]] and certain regions of the [[Himalayas]], including northern [[Nepal]], [[Bhutan]], and [[India]] (particularly in {{Wiki|Arunachal Pradesh}}, {{Wiki|Ladakh}}, {{Wiki|Dharamsala}}, Lahaul and Spiti in {{Wiki|Himachal Pradesh}}, and {{Wiki|Sikkim}}). It is the state [[religion]] of {{Wiki|Bhutan}}. It is also practiced in {{Wiki|Mongolia}} and parts of {{Wiki|Russia}} ({{Wiki|Kalmykia}}, {{Wiki|Buryatia}}, and {{Wiki|Tuva}}) and {{Wiki|Northeast}} [[China]]. Texts [[recognized]] as [[scripture]] and commentary are contained in the [[Tibetan Buddhist canon]], such that [[Tibetan]] is a [[spiritual]] [[language]] of these areas. |

A [[Tibetan]] diaspora has spread [[Tibetan Buddhism]] to many Western countries, where the [[tradition]] has gained popularity. Among its prominent exponents is the [[14th Dalai Lama]] of [[Tibet]]. The number of its adherents is estimated to be between ten and twenty million. | A [[Tibetan]] diaspora has spread [[Tibetan Buddhism]] to many Western countries, where the [[tradition]] has gained popularity. Among its prominent exponents is the [[14th Dalai Lama]] of [[Tibet]]. The number of its adherents is estimated to be between ten and twenty million. | ||

Revision as of 18:14, 12 September 2013

Tibetan Buddhism is the body of Buddhist religious doctrine and institutions characteristic of Tibet and certain regions of the Himalayas, including northern Nepal, Bhutan, and India (particularly in Arunachal Pradesh, Ladakh, Dharamsala, Lahaul and Spiti in Himachal Pradesh, and Sikkim). It is the state religion of Bhutan. It is also practiced in Mongolia and parts of Russia (Kalmykia, Buryatia, and Tuva) and Northeast China. Texts recognized as scripture and commentary are contained in the Tibetan Buddhist canon, such that Tibetan is a spiritual language of these areas.

A Tibetan diaspora has spread Tibetan Buddhism to many Western countries, where the tradition has gained popularity. Among its prominent exponents is the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet. The number of its adherents is estimated to be between ten and twenty million.

Contents

- 1 Bon religion in Tibet

- 2 Beginning of Buddhism in Tibet

- 3 Coming of Padmasambhava

- 4 The Council of Lhasa

- 5 The Dark Age of Tibetan Buddhism

- 6 Second dissemination of Tibetan Buddhism

- 7 Tibetan Buddhism in Mongol

- 8 The hierarchy of Dalai Lama

- 9 The 'Great Fifth'

- 10 Tibetan Buddhism in 20th Century

- 11 Tibetan Buddhism and Vajrayana

- 12 Some traditions of Tibetan Buddhism

- 13 Kanjur and Tanjur

- 14 Four schools in Tibetan Buddhism

- 15 Common characteristics of all schools

- 16 Popularity of Tibetan Buddhism in the west

- 17 Preliminary practices

- 18 Tantric Initiation

- 19 Channel, Wind and Drop

- 20 Practices for Developing Compassion

- 21 Dzogchen (The Great Perfection)

- 22 Mahamudra

- 23 Death and Dying

- 24 Source

Bon religion in Tibet

Tibetan Buddhism is considered one of the last great religions still alive in the world today. Tibetan Buddhism is not restricted to Tibet, though this tradition is named after it. It has had great influence to central and northern Asian countries, such as Mongolia and Bhutan. It is now well known in the modern western world. In fact, Tibetan Buddhism is a name given by the western people.

Same as all other Buddhist schools, Tibetan Buddhism originated from India, where the World Honor One, Shakyamuni Buddha was born more than 2500 years ago. However, Buddhism in Tibet has a history that spans more than a thousand years.

As one of the religious traditions in Tibet, Bon religion still survives today, but has been interpreted in the Buddhist framework. In the sixth century, Tibet became a powerful country under the reign of Songstsen Gampo (AD 609-649), who attacked the neighboring nations, such as the Chinese and Ottoman empires. In 635, he married a Chinese princess and a Nepalese princess. Both princesses were Buddhist devotees, who introduced Buddhism to Tibet with the great influence to the king. These princesses were later regarded as incarnations of the goddess Tara - the emanation of all the Buddhas' wisdom and compassion, known as 'the mother of the Buddhas'. Songstsen Gampo is regarded as the founder of the Tibetan Buddhism in royal dynasty.

Beginning of Buddhism in Tibet

During the reign of 38th Tibetan king, Trison Detsen (740-798 AD), the grandson of Songstsen Gampo, he established Buddhism as the state religion. In AD 770, Trison Detsen invited the philosopher and abbot Shantarakshita from India. However, they encountered strong opposition from the local noble families, and also the disturbance from the local spiritual forces and deities, such as Nagas, snake-like spirits. Shantarakshita suggested the king to invite a Vajrayana master to overcome these difficulties. Later, he invited the Indian Tantric Yogi, Padmasambhava, to come to Tibet to spread Buddhism. He also built the first Tibetan monastery at Samye Ling, 35 miles southwest of Lhasa, where Padmasambhava translated the Buddhist scriptures from Sanskrit to Tibetan.

Coming of Padmasambhava

For most Tibetan Buddhists, Padmasambhava is regarded as a second Buddha. When he was eight years old, he appeared on a lotus flower in the middle of Lake Dhanakosha in Oddiyana, a place probably in the border of Afghanistan and Pakistan.

When the king, Trison Detsen and his ministers found Padmasambhava in Nepal, he invited him to Tibet in the propagation of Buddhism. Accepting the king's offer, he had to, first of all, remove many obstacles facing the local people. Thus, on the way to central Tibet, he overcame the challenges of the local native Tibetan deities by the force of his magical power, and converted the Tibetan demons and gods, who were bound to become the guardians of Buddhism in Tibet.

Arriving at Samye, Padmasambhava was greeted by the King and his court. Later, Shantarakshita ordained the first Tibetan monks, a group of seven selected young men known as the 'seven probation monks'.

He further bestowed the Vajrayana teachings and Tantras upon a group of 25 disciples, including the king and various scholars, such as Vairocana and Yeshe Tsogyal (a young Tibetan woman). The teachings comprised of three sets of practices, namely, Mahayoga, Anuyoga and Atiyoga. Padmasambhava first initiated each of the 25 disciples into one of the 'eight major deities' of Mahayoga. Yeshe Tsogyal herself became an adept of the deity Vajrakilaya. Accompanying these initiations, Padmasambhava also gave some instructions on Anuyoga, and Atiyoga, the climax of all teachings. Atiyoga introduces the devotees directly to the primordial state of enlightenment, which was the greatest of all spiritual teachings that Padmasambhava had brought with him from India.

Apart from the conversion of the local demons and gods and the transmission of the Tantric teachings to his disciples, another great act of Padmasambhava was the concealment of a multiplicity of teachings intended for the benefit of future generations of the Buddhist devotees. These teachings, subsequently known as 'Terma' (means treasures), comprised spiritual instructions, which were to be discovered and decoded in later centuries by masters whose minds had been blessed by Padmasambhava himself. These masters were later known as 'Tertons' (means treasure revealer). The preservation of his teachings as Terma is still influential in Tibetan Buddhism at a later time, even nowadays.

Eventually, Padmasambhava left Tibet to work for beings in other lands. However, he assured his followers that he would never truly be apart from them as his compassion was beyond near and far. He told them that on the holy tenth day of each month, he would come riding on the sun's rays from the Palace of Lotus Light to bless his faithful followers. His promise has remained unbroken down to the present days.

The Council of Lhasa

Upon the departure of Padmasambhava from Tibet, a great debate took place in Lhasa between the followers of Shantarakshita and Padmassambhava of Indian origin, and the Chinese Buddhists. The former proposed to take a gradual approach to enlightenment, while the latter promoted the sudden enlightenment. Finally, the Indian party led by Kamalashila won the victory of the debate. Trison Detsen ordered that only the Buddhist teachings from India would be followed in Tibet.

The Dark Age of Tibetan Buddhism

In mid 9th century, the great conqueror king, Ralpachen (AD 806-841), continued to spread Buddhism throughout Tibet. He is regarded as the third Dharma King of Tibet. Unfortunately, he was murdered by his ministers, who replaced the king with his brother, Langdarma. Langdarma was a supporter of the old Bon religion. Langdarma destroyed Buddhist scriptures, closed down the monasteries and forced the monks to marry. Though he was eventually assassinated, the Tibetan empire, just as the Tibetan Buddhism, collapsed into chaos. The dark period for Tibetan Buddhism lasted for some 150 or more years. Tibet did not unite under a common leadership again for another three hundred years.

Second dissemination of Tibetan Buddhism

The second dissemination of Tibetan Buddhism was brought about by Yeshe O, who was the king in the western part of Tibet. The lineage of lay Vajrayana practitioners still survived after the dark age of Tibetan Buddhism, though the monastic and scholarly forms were severely destroyed. Many influential rulers in western Tibet desired to re-establish the entire Tibetan Buddhism. They sponsored translators to India as well. Thus, the second period of transmission of Buddhism in Tibet is often called 'the period of the new translations'.

In 1042, the king invited the renowned scholar, Atisha Dipankara Shrijnana (AD 979-1053). He set out a graduated path to enlightenment, known as 'Lam-rim', stipulated in his book 'The Lamp of the Path to Enlightenment'. He also reformed the monastic disciplines, particularly the mentor-student relationship of Lamas and disciples. Being the master of the second transmission of Buddhism in Tibet, his works had a great impact on Tibetan Buddhism, not just in the royal family but also the society. He turned the warrior-like Tibetans to the Buddhists seeking for peace. With his effort, Buddhism was firmly established in Tibet.

This period marked the development of major schools in Tibetan Buddhism, and distinguished between the old and the new transmission periods.

Tibetan Buddhism in Mongol

In the 12th century, the Mongolian army invaded and conquered Tibet. In 1244 AD, the Mongolian warlord Prince Godan invited the head of Sakya school, Sakya Pandita, to his camp. Sakya was another school of Tibetan Buddhism developed at that time, apart from Nyingma school established by the distinguished Padmasambhava. Godan was very impressed by this learned Tibetan Lama and was converted to Buddhism. This marked the beginning of the extraordinary priest-patron relationship between the two countries.

In 1253, Sakya Pandita's nephew, Pagpa, became the spiritual teacher of Kublai Khan. Kublai Khan delegated Pagpa as the ruler of Tibet. Kublai Khan later became the Mongol emperor of China, and declared Buddhism the state religion.

The close relationship between the Tibetan Lamas and the Mongolian Khans had declined since 1307, and Mongolian dynasty was taken over by the Chinese again in 1368.

The hierarchy of Dalai Lama

Around 1400, Tsong Khapa reformed the Tibetan Buddhism, and founded the Gelug school. This school, known as the 'yellow hats', became very popular in Mongolia as well as in Tibet. In 1578, the Mongol ruler Alta Khan met Sonam Gyatso, said to be the second reincarnation of Tsong Khapa's amin disciple. Like Prince Godan, the great Khan was impressed by this spiritual leader and was converted to a Buddhist. He bestowed the title 'Dalai' on Sonam Gyatso, as an acknowledgment to his deep understanding in Buddhism. The institution of Dalai Lama was then crested.

Sonam Gyattso was the third Dalai Lama, as his previous two incarnations (Gendun Gyatso and Gendun Druba) were given the same title posthumously. The Fourth Dalai Lama was given to the Alta Khan's family, and this secured the relationship between the two countries. The Fourth Dalai Lama became the political as well as the spiritual leader of Tibet.

The 'Great Fifth'

In 1642, the 'Great Fifth' became the first Dalai Lama to lead a united Tibet. He wrote many books and mastered the Tantric arts. Being a powerful leader, he gained hegemony over the military in Tibet, and was well respected by the Tibetans. Due to the political stability and independence, Tibet enjoyed three uninterrupted succession of Dalai Lamas peacefully.

Tibetan Buddhism in 20th Century

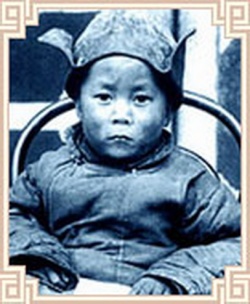

The 13th Dalai Lama (1876-1933) was a great ruler who planned to improve the economy and the education system, and to reform the monasteries. Unfortunately, Tibet was invaded by the British army and forced to sign the unfair trade agreement. Moreover, the Chinese general Chao Erh-feng organized a number of brutal raids into Tibet, and attempted to capture the 13th Dalai Lama. The 13th Dalai Lama had to flee to India and died in 1933 when the political situation of Tibet was still in chaos.

In 1937, Reting Rinpoche succeeded in searching the reincarnation of Dalai Lama in Eastern Tibet. After a number of tests and verifications, the 4-year-old boy was enthroned as the new Dalai Lama, 14th in his line. That is the Dalai Lama today, who was born in 1935. His name is Tenzin Gyatso.

Tibetan Buddhism and Vajrayana

In Buddhism, it can be classified into Esoteric Buddhism and Exoteric Buddhism. In Buddhist doctrines, the latter, also known as Vyukta-upadesa in Sanskrit, emphasizes on phenomenological perception, while the former, also known as Guhya-upadesa in Sanskrit, emphasizes on ontological perception. Amongst the ten great sects of Chinese Buddhism, apart from Cheng Yen sect (see Chapter 75 to Chapter 79), all other sects are classified as Exoteric Buddhism. Tibetan Buddhism is the most typical and popular Esoteric Buddhism nowadays.

In terms of vehicle (or known as Yana in Sanskrit), Tibetan Buddhism, as commonly claimed by esoteric Buddhism, is regarded as Vajrayana , as compared to Hinayana and Mahayana . Vajra is a symbol derived from mythical thunderbolt of Indian deity called Indra, which represents non-destructiveness, and many other meanings.

Though all of them have a common objective of attaining Buddhahood, Vajrayana claims to be the very expedient one accomplishing in one life time, while it might take countless lifetimes or so-called Three Asamkhyeya in Hinayana and Mahayana. The former is known as the Tantra tradition , while the latter is known as the Sutra tradition.

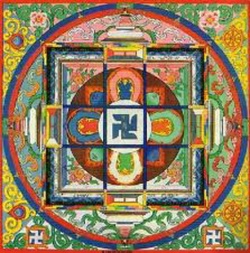

Tantra means "continuous stream", which describes a continuum that takes a practitioner from ignorance of an ordinary being to enlightenment of a Buddha. Tantra is a collective term for complex meditative practices that use the methods of ritual symbolic visualization for transforming one's experience of conventional reality of body, speech and mind into a fully enlightened Buddha. Tantras include the Mandalas (sacred diagram), Mantras (magic spells), Mudras (hand gestures), etc.

The essence of the Vajrayana is the symbolic use of imagined divine forms, which represents one and the same time the five Skandhas, five points of space, the five evils, the five wisdoms, usually represented by the Five Buddhas, namely Vairocana, Aksobhya, Ratnasambhava, Amitabha and Amoghasiddhi.

Varjayana, as represented by Tantric Buddhism, is regarded as the highest and most sacred stage in the development of Buddhism. Vajrayana is a path of the most direct nature imaginable. Tibetans consider the Tantric practices to be the most potent and efficient method of attaining enlightenment.

Features of Vajrayana Buddhism

As compared to the Mahayana Buddhism, the development of Vajrayana demonstrates the following features:

- It transforms one's body, speech and mind -- The aim of Tantric practice is to transform one's body, speech and mind into those of a fully enlightened Buddha by special Yogic means. Thus, a variety of ritual and magical methods have been devised, involving the use of specialized forms such as Mandala, Mantra and Mudra, bell (Ghanta) and hand drum (Damaru), which is believed to produce powerful spiritual effects.

- It points out the "view" in the direct manner -- "View" here means the nature of reality as it is. It is not merely explained through reasoning, nor by analogies that allow us to understand that all phenomena are empty, but can be "seen" face-to-face through the Vajrayana practices. It is not just conceptual, but can be experienced during the course of the initiation and the subsequent meditation practices.

- It has many skilful means -- a comprehensive and systematic path for the practitioners to follow, such as wisdom, prosperity, health, etc. step-by-step to achieve one's goals. The supreme skilful practices of Anuttara Tantras allow the practitioners to achieve complete realization in this very life.

- It is without difficulties -- In traditional Buddhist teachings, one has to avoid any object of the sense, as it causes us to remain in suffering and in illusion. The Vajrayana approach is based upon the underlying or inherent purity of all things, which are utilized as part of the very process of awakening. This approach may be easier in the sense that it does not require austerity.

- It is for those with the sharpest faculties -- It is said that those practitioners with most skill can achieve Buddhahood in this very life through Vajrayana.

Some traditions of Tibetan Buddhism

Being a Tantric practitioner in Tibet, he must find a suitable master called Guru (or called Lama in Tibetan Buddhism) to act as his spiritual preceptor, in order to be guided through the complex and powerful meditation. Once the practitioner finds one with whom he has a personal affinity, he must prove his sincerity purity and resolve to Guru before he is accepted to be a disciple (or called Chela in Tibetan Buddhism); for his spiritual welfare will then be responsibility of the Guru's instructions as a patient obeys the instructions of his doctor. He should also serve and have great devotion for his Guru.

After the practitioner has carried out a number of strict "preliminaries" to purify himself, his Guru will initiate him into Tantric practices (or known as Tantric initiation). An initiation (Abhiseka in Sanskrit) signifies the following:

- It helps to remove the spiritual obstruction - sprinkling water upon the practitioner.

- It transmits a spiritual power from the Guru, i.e. "empowerment" in Tantric practice.

- It permits access to a body of the scriptures and the oral instructions required to understand and practice them properly.

- It authorizes the practitioner to address himself in a particular way to a certain deity (called Yidam in Tibet, which means 'to link the mind'.

The details of preliminaries and Tantric initiation will be discussed later.

At the initiation, the Guru chooses a Mantra and a Yidam appropriate to the practitioner's character type, and introduces him to the Mandala (mystic circle or sacred diagram) of the Yidam. To realize the enlightened state, the practitioner must do more than meditate on Emptiness, he must meditate or visualize also on the Buddha's form, and regard himself as an embodiment of that deity with all qualities. Through meditation on the Buddha's form, the practitioner perceives the entire universe as a Buddhaland or Pure Land; through meditation on the Buddha's speech, he perceives all sound as the sound of Mantra; through meditation on the Buddha's mind, he experiences all thought as the radiance of pure awareness. The details of Mandala and Yidam will be discussed later.

In Tibet, a Guru is generally called a Lama. A Lama need not be a monk. Only his knowledge and skills in Tantric practices count. The Lama plays such important role in Tibetan Buddhism, which is often called Lamaism. Generally, the practitioner (Chela, i.e. student) should follow the instructions from his teacher (Guru, i.e. mentor) in the lineage of a particular school. Apart from taking refuge to the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha, the practitioner should take refuge to his Guru as well.

One of the main duties of the Lama is to guide a dying person as the spirit, or commonly called "soul", left his body. For 49 days, the spirit exists in Bardo, the state between death and rebirth. During this period, the instructions given by the Lama will help the Bardo reach either rebirth or enlightenment. The importance of Bardo state is always stressed in Tibetan Buddhism.

Another tradition of Tibetan Buddhism is the hierarchy of Dalai Lama. On the death of a Dalai Lamaa search begins for the child who is his latest incarnation. Once found, the child is educated by the elder Lamas in the preparation of his role of being the Dalai Lama again.

Kanjur and Tanjur

Tibetan doctrine recognizes three vehicles to reach the final goal of Buddhism. The methods take into account the different levels of spiritual development of the practitioners. The first is Theravada or Hinayana, which brings the practitioner to the goal of self-emancipation through self-discipline. The second is Mahayana, which is the path to philosophical insight for the sake of saving others. The third is the Vajrayana, which is the way of Tantric rites and mystical meditations, or visualization. The Tantric practitioners may take 14 to 20 years to study the first two vehicles before they are ready for the Tantras.

The great scholar and writer Buston (1290-1364) divided all translated canonical and sub-canonical works, as well as commentaries and independent writings into two parts:

- Kanjur - "translated word" containing works attributed to the historical Buddha Shakyamuni, to various transcendent Buddhas and to the Tantric divinities identified as Buddhas

- Tanjur - "translated treatise" containing translated writings of Indian scholars and teachers.

The Kanjur comprises 100 or 108 printed volumes and the Tanjur comprises 225 volumes. These vast collections of Indian Buddhist literatures provide the doctrinal basis for Tibetan Buddhism. The most significant parts are:

- Texts on monastic discipline -- those of the Indian Buddhist school known as Mulasarvastivadin, closely related to Vinaya texts of the Theravadin.

- Literature on the "Perfection of Wisdom" -- providing philosophical basis of Tibetan Buddhism.

- Great Mahayana Sutras -- Sutras expounding the doctrines of Middle Way, Mere-consciousness, etc.

- Tantras -- including the descriptions of the great divinities and their respective sets of Mandalas, collections of Mantras by which the divinities are invoked, the rites and symbols, etc.

Four schools in Tibetan Buddhism

Nyingma

Literally, Nyingma means "the ancient ones" thus it represents the traditional school in the ancient transmission period. It is originated from the collaboration between King Trison Detsen and the Indian masters, Shantarakshita and Padmasambhava. As the origin of the lineage, the Tantric teachings of Padmasambhava are especially important in the Nyingma school.

The early masters were known as Ngakpas, i.e. "Tantric Yogins", who mastered and preserved the oral transmission teachings of Padmasambhava. They continued the transmission through the dark period of Tibetan Buddhism between 9th and 11th centuries. As more and more Termas or "treasures" deposited by Padmasambhava were discovered by the Tertons or "treasure revealers" in the 11th century, this school was revitalized and strengthed.

One of the greatest masters after Padmasambhava in Nyingma school was Longchenpa or Longchen Rabjam (AD 1308-1363). He composed over 250 works. He also delineated nine vehicles of Dharma in the categorization of Buddhism, namely,

- Sravakayana

- Pratyekabuddhayana

- Bodhisattvayana

- Kriya Tantra

- Upa Tantra

- Yoga Tantra

- Mahayoga Tantra

- Anuyoga Tantra

- Atiyoga Tantra

The first two refer to Hinayana, and the third is ordinary Mahayana. The next three Tantras are the "outer" Tantra, while the last three Tantras are the "inner" ones. The six Tantras refer to the six perfections. "Drok chen" the "Great Perfection". The crowning glory of the Nyingma teaching is found in the Ayiyoga Tantra vehicle, the highest of the nine.

There are other great masters, such as Rigdzin Jigme Lingpa (AD 1729-1797), Patrul Rinpoche (AD 1808-1887).

Amongst the four major schools of Buddhism in Tibet, Nyingma has been the least monastic. It is always referred as "red school"

Sakya

Sakya literally means "grey earth". This school began in 1073 with the foundation of a meditation center in the province of Tsang at Sakya. The center was founded by Master Konchog Gyalpo of Khon clan. In mid 11th century, Konchog Gyalpo and his brothers found that many of the traditional Tantric practices of Padmasambhava were modified and compromised by some adherents. They looked for the new Tantras propagated by Drokmi Lotsawa, who was later appointed as the Lama of Konchog Gyalpo.

Kunga Nyingpo (AD 1092-1158), the son of Konchog Gyalpo, also known as "the Great Sakyapa", began the process of enriching the Sakya school in both philosophical and Tantric teachings by some great masters. The expansion of the school continued with the efforts of his sons, Sonam Tsemo (AD 1141-1182) and Jetsun Drakpa Gyaltsen (AD 1147-1216).

Sakya Pandita Kunga Gyaltsen (AD 1182-1251), the grandson of Kunga Nyingpo, usually known as "Sakya Pandita" ("the Sakya scholar"), was the fourth and perhaps the greatest master of the early Sakya school. He was famed as the only Tibetan master to possess the outer signs and characteristics of a fully enlightened Buddha. He was said to be the incarnation of Manjushri because of his spiritual accomplishment and extensive knowledge in all aspects.

Chogyal Phakpa (AD 1235-1280), nephew of Sakya Pandita, became the Lama of the famous Mongol Emperor, Kublai Khan. Later, the Klan established the Sakya school as the ruler of Tibet, a position which they held for the next 75 years.

Following the decline of secular power, the Sakya school concentrated entirely upon spiritual matters, and later split to two great sub-sects, namely, the Ngor, founded by Kunga Zangpo (AD 1382-1457) and the Tshar, founded by Losal Gyamtso (AD 1494-1556).

For the spiritual teachings of Sakya school, the most significant one is the cycle known in Tibetan as "Lamdre", which means "the Path and its fruit". It is originated from the mystical experience of an Indain Yogin, Virupa in the 9th century. The Lamdre provides a systematic approach through meditation practices of both the Sutras and Tantras. It highlights the "inseparability of Samsara and Nirvana", as it says in the Hevajra Tantra, "By rejecting Samsara one will never find Nirvana". Similarly, one will understand the difference between Buddhas and ordinary beings is that the latter do not recognize their own true nature.

This school is sometimes called 'flower school', with the mix of red, white and blue.

Kagyu

Both Sakya and Kagyu are the principal schools developed during the transmission of new Tantras, the form of Vajrayana in the 11th century. While the Sakya school is marked for its eminence in scholarship and Tantric ritual, the Kagyu school is characterized by its meditation and yogic practices. The Kagyu school was founded by Marpa (AD 1012-1097), and Milarepa (AD 1040-1123).

Marpainherited the teachings from accomplished masters such as Naropa and Maitripa in India, and established the core syllabus for Kagyu practitioners to practice. The essence of the teaching is known as Mahamudra ("the Great Seal") and "Six Dharmas of Naropa", both of which are actually part of Anuttara Tantra. The former is concerned about the actual direct experience of nature of mind itself, while the latter comprises techniques for gaining some spiritual powers. Marpa married Lady Dagmema and had several children in a rich family. However, his followers recognised him as a Buddha in person.

Milarepa was a great ascetic and foremost master and a poet, who received the lineage from Marpa. He was born in Tibet, and became a student of Marpa at the age of 38. He received the precious Vajrayana instructions from Marpa, and then he spent many years meditating upon them in the snowy mountains of Tibet and Nepal, dressed only in a white cotton robe. He attained the highest level of realization, and transmitted it to his disciples in formal initiations and instructions, as well as his inspiring poems and songs.

Gampopa (AD 1079-1173) was the chief student of Milarepa. Before that, he had spiritual training in the Kadam school. So, Gampopa synthesized the monastic disciplines and non-Tantric path of Kadam school with the Tantric teachings of Milarepa. The Kagyu sect spread rapidly and widely through Tibet in the next two generations. The Kagyu school quickly split into numerous sub-sects, known as "four great" and "eight minors" schools headed by Gampopa's chief disciples.

Amongst these sub-sects, Karma Kagyu set forth the recognition of reincarnated Lamas. This custom began in the 13th century with the discovery of Karma Pakshi, the reincarnation of Karmapa Dusum Chenpa (AD 1110-1193), who had established the Karma Kagyu school to this present day, aided by other great incarnations such as the Shamar and Tai Situ Lamas.

Mahamudra is the key meditation cycle of all Kagyu school in Tibet. The enlightened masters "seals" or certifies everything that arises within his field of experience worth his understanding of emptiness. The whole phenomenal world is nothing other than mind, but mind itself has no essence by which it can be grasped. Mind and phenomenal world are inseparable and empty. This unity is all-embracing and eternal. Mahamudra was systematized by Gampopa into a graded series of practices.

Similar to the Nyingma school, the practitioners have to accomplish the outer and inner preliminaries. Then they are instructed to practice Shamatha, and then Vipashyana.

Shamatha, "calm abiding", is like Trek-cho in Nyingma school. Besides Shamatha, the Kagyu practitioners have to meditate on the goddess Vajravarahi as the development stage and then the Yogas of the Six Dharmas of Naropa as the completion stage. The six elements are the Yogas of heat, luminosity, illusory body, dream, transference of consciousness and the intermediate state (Bardo).

Then the practitioners can proceed to Vipashyana, the development of insight into the nature of mind. At this point, one receives "direct introduction to the nature of mind" from one's Lama. It can be effected through words, symbols, or even direct mind-to-mind transmission. Whatever arises from one's mind is simply the manifestation of the Dharmakaya itself, since our mind is the Dharmakaya and the ultimate reality of all Buddhas.

This school is sometimes called 'white school'.

Gelug

Gelug literally means "system of virtues". This school is known as the "Yellow Hats" and is extremely popular in Mongolia and Tibet.

In 14th and 15th century, the transmission of Buddhism from India to Tibet ceased, and Buddhism was entirely Tibetan. The founder of Gelug, Tsongkhapa (AD 1367-1419) was born in Tibet, who inherited the teachings and practices for his new traditions from Tibetan masters of other school, without going to India. He included Sakya philosophical works and meditative practices from Kaygu, Sakya and other schools. Most importantly, he drew upon the 'graduated path' approach of Atisha and the Kadam school. So his followers became known as the 'new Kadam'. In his teachings, he developed his own version of Madhyamaka. He also promoted the study of logic and epistemology. Tsongkhapa was perhaps the most notable for his strict observance of the monastic disciplines as set forth in the Vinaya.

Tsongkhapa preached in his monastery of Ganden, some 35 miles from Lhasa. Shortly after, two other monasteries was built in Sera and Dreprug. Over the next two centuries, the school developed rapidly with the strong support from the disciples. In 1578, Sonam Gyatso, the second reincarnation of Tsongkhapa's main disciple visited the Mongolian ruler Alta Khan, who was deeply moved. The king then became a Buddhist and bestowed the title "Dalai" - the Mongolian word for ocean - on Sonam Gayato, as a recognition on his profound knowledge on Lamaism. Thus, the monk-patron relationship was re-established and the institution of Dalai Lama was created.

Sonam Gyatso is known as the Third Dalai Lama, as his previous two incarnations (Gendun Gyatso and Gendun Druba) were given the title posthumously. The Fourth Dalai Lama came from Alta Khan's family, and this linked the relationship between the two countries.

In 1642, a high-ranking master of the school, the fifth Dalai Lama, Ngawang Losang Gyamtso (AD 1617-1682), was put on the throne of Tibet by Mongol intervention. Gelug was then regarded as the state monastic order throughout the major parts of Tibet. It should be noted that the Dalai Lama, who, in a succession of incarnations since 1642 has been the king of Tibet, is not actually the head of the Gelug school. The role of the head is an elected abbot in the monastery of Ganden, the first Gelug monastery founded by Tsongkhapa. The "Great Fifth" became the first Dalai Lama to lead a united Tibet. He was also invited by the first Manchu emperor, as many subsequent Dalai Lamas did, the spiritual leader to the Chinese rulers.

Common characteristics of all schools

The similarities of all schools are actually greater than their differences, for instance,

- All schools accept the threefold structure, namely Hinayana, Mahayana and Vajrayana, both in terms of historical development of Buddhism and within the spiritual life of individual. They all regard the Varjanana or Tantric Buddhism represents the highest and most sacred stage in the development of Buddhism.

- All schools accept the same scriptures as their canonical basis. These scriptures comprise of the Kangyur (100-108 volumes) and the Tangyur (225 volumes). The Kangyur comprises Tibetan translations of the Sutras and Tantras by Sakyamuni Buddha, such as the Perfection of Wisdom, the Saddharma-pundarika, the Lankavatara,etc. The Tangyur consists of translations of commentaries and other expository works by the great masters, such as Nagarjuna, Dharmakirti, etc.

- The monks of all schools follow the same Vinaya, the same manner of monastic life and observance.

Popularity of Tibetan Buddhism in the west

Tibetan Buddhism was first known and popular in the west by the 19th century when the Theosophical Society was founded by Madam Helena Petrovna Blavatsky. Some may think that Tibetan Buddhism was not really Buddhist, as it is quite different from the traditional Buddhism typified by Theravada or Chan, which emphasize philosophical, intellectual approach. It has its uniqueness in religious traditions. In fact, the name of Tibetan Buddhism is called by the westerners, while the Buddhist devotees in Tibet classify their religion, in common, as Vajrayana Buddhism or Tantric Buddhism.

Amongst the four schools, Gelug and Kagyu traditions are so far more popular in the western countries. For Kagyu school, the sub-sect Karma Kagyu is the most influential one. Sakya is perhaps the slowest to spread in the west, and is often described nowadays as the smallest of the four schools. Nyingma has made a quieter impact as compared with Gelug and Kagyu.

Preliminary practices

The preliminary practices are the approach in the preparation for the Tantric practice. In Tibet, it is known as Ngondro, which means 'something that goes before'. There are two kinds of preliminary practices, the first is the common / ordinary and the second is special / particular.

Common or Ordinary Preliminaries -- Four Thoughts

It involves 'four thoughts' that can turn one's mind towards the practice of Dharma providing a solid foundation for the Tantric practice.

- Appreciation of the precious human existence -- In Tibetan, it is called Dal-jor, which means a freedom or opportunity difficult to come by. One has to take the precious opportunity of being a human being on Earth in this period of eon, so that one has the freedom to allow for the spiritual development. There are many kinds of life existence, known as Eight Hindered Existences. In some, one has no chance to learn and practice Buddhism.

- Awareness of impermanence of all phenomena -- Referring to the Three Dharma Seals or Three Universal Truths, one should have a thorough understanding of the Truth of Impermanence, the Truth of No-self, and the Truth of Nirvana. As Milarepa said, " It was the fear of death that drove me to the mountains, and I meditated for so long on death and impermanence that I realized the deathless state of mind. Now, death holds no fears for me."

- Understanding the concept of Karma -- It is the causality between actions and experience. It is the most significant belief in Buddhism, which explains all causes and effects in the past, present and future. With the understanding of Karma, we can take virtuous actions, which can produce positive results in happiness and fulfillment, and can prevent harmful or evil actions, which would otherwise bring us suffering and pain.

- Awareness of the sufferings and limitations of Samsara (i.e. reincarnation) -- We human beings suffer from birth, aging, sickness and death. We have severe afflictions, emotion and delusion, etc. due to our ignorance. The only solution of relieving us from suffering is attaining enlightenment. The practice of Prajna (or Wisdom) is the only way that can break off our ignorance.

Special or Particular Preliminaries -- Four Mula Yogas

They are known as Four Foundation Yogas, or Mula Yogas, which form the basis of Tibetan spiritual practices. Mula is a Sanskrit word meaning root and foundation, while Yoga simply means 'that unites'. It is considered as the entrance to the Vajrayana, and is common in all Tibetan Buddhist school in general.

1. First Foundation Yoga -- Refuge and Prostration

In Tibetan Buddhism, apart from taking refuge in the Three Jewels (i.e. Buddha, Dharma and Sangha), the practitioner has to take refuge in the Three Roots as well. The three roots are, namely, the Guru as the root of blessing, the Yidam or meditation deity as the root of accomplishment, and the Dakini or Dharma protector as the root of enlightenment activity.

It consists of three main elements, namely, prostration, recitation and visualization, corresponding to body, speech and mind respectively. These three modes of functioning correspond to the Threefold Body, namely. Nirmanakaya, Sambhogakaya and Dharmakaya respectively. The mental element of the first Mula Yoga is the visualization of the so-called Refuge Tree, which is made up of various images, such as lotus flower, Tantric deities, Bodhisattvas and Buddhas. The verbal element of this Mula Yoga consists of reciting aloud a series of verses expressing one's determination of taking refuge. One takes refuge in the founder of the tradition - Padmasambhava for the Nyingma school - as the embodiment of all the Refuges. Finally, the physical element of this Mula Yoga is prostration. Tibetan Buddhist devotees prostrate fully and rather dramatically, flat on their faces with their arms stretching out in the front. They can prostrate in full-length manner for a distance of several hundred miles. One may think that it is crazy to do so. However, according to tradition, one vows to up 100,000 prostrations. This Foundation Yoga represents the Hinayana component of Buddhism, which is regarded as the Basic Buddhism, concluding in taking refuge in the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha.

2. Second Foundation Yoga - Development of the Bodhicitta

The second Mula Yoga is the arising of Bodhicitta, the desire towards Enlightenment for the benefit of all living beings, The practitioner has to recite it for 100,000 times. (It is a common characteristic of the Vajrayana that one does a practice for 100,000 times, because the repetition can help penetrate into one's unconscious mind.) Thus, one has to develop kindness and compassion for all beings, as well as to cultivating sympathetic joy and equanimity. Although such practices are common in both Hinayana and Mahayana, people usually consider Mula Yoga as representing the Mahayana component of Buddhism.

3. Third Foundation Yoga -- Meditation and Mantra Recitation of Vajravatta

The purpose of this Foundation Yoga is to purify oneself of different kinds of obscurations, confusion and negativity. Four forces or powers are required:

- The supportive force from the individual commitment of the Hinayana, the Bodhisattva vows of the Mahayana, or the Tantric Samaya or commitment of the Vajrayana

- The force from meditating Vajrasattva, reciting the Mantra, as a process of visualized purification

- The force from repentance or remorse

- The force from the strong will or commitment to purify ourselves of hindering and harmful effects.

The Vajrasattva meditation is the single excellent and effective practice for purification that is found in the Sutra or the Tantra teachings. It involves a series of complex visualization of objects, seed syllables of the Mantra, etc. (which is not to be elaborated here) The effectiveness of the purification can be assessed from the external signs/indications, such as the sun or moon rising in the sky, finding ourselves in a beautiful meadow or at the peak of high mountain, etc.

4. Fourth Foundation Yoga - The Offering of the Mandala

The Mandala practice enhances the positive factors in attaining enlightenment. According to traditions, two small metal plates, called the Mandalas, are used as a basis for meditation. One of them is placed on the shrine, with five piles of rice in a pattern, one in the center and one in each of the four directions. This forms the basis for the visualization of the sources of refuge, the Three Jewels and the Three Roots, in the sky in front of the practitioner. The other Mandala is held in the hand for making offerings.

The actual visualization is built in stages. The first step is to create an idealized conception of the universe in four directions, then the seven attributes of the universe monarch (wheel, gem, consort, minister, elephant, horse and general), and then the eighth attribute is a great vase filled with treasures, which represent the eight cardinal and inter-cardinal directions, including East, South, West, North, SE, SW, NE, NW.

Next, the eight offering goddess are visualized in the cardinal directions, namely, the goddess of joy, the goddess of flower garlands, goddess of song, and the goddess of dance, then the other four in the inter-cardinal directions, i.e. goddess of flowers in SE, goddess of incense in SW, goddess of lamps, light and illumination in NW, and goddess of perfumed water in NE. The next elements are the sun and the moon, the world systems of greater and greater order of magnitude. One meditates and allows the mind rest in a state of formlessness, non-conceptual awareness and tranguility.

In making offering, one should not simply benefit oneself, but benefit all beings out of compassion.

Tantric Initiation

After the preliminary practices, the formal Tantric practice begins with initiation. Initiation is known as Abhiseka in Sanskrit, which literally means 'sprinkling'. It is a kind of empowerment by a master called Guru. The emphasis on the need of a guru is one of the essential characteristics of the Tantric meditation. It is obvious that Tantric meditation cannot be practised without a Guru, which is different from the Hinayana and Mahayana meditation. Thus, it does not just mean being taught the method of meditation by a guru, but is an initiation supervised by a guru.

The equivalent word of Abhiseka that the Tibetans use is 'Wongkur', which means transmission of power, rendering the inner meaning of Abhiseka. In other words, the Tantric initiation is essentially a transmission of spiritual power from the Guru to the disciple. This is symbolized by the sprinkling of water, and very often embodied in a Mantra, a sacred syllable or phrase to be repeated over and over again, which is given at the time of initiation.

It may be misinterpreted that Vajrayana emphasizes 'other-power' of the designated deity (called Yidam in Tibet) through initiation, which is actually very limited. The practitioner is not really blessed and protected by the deity, but is required to subdue his own mind through meditation, thus to control his consciousness through contemplation or visualization. If the Tantric practitioner does not practice contemplation, they will have no progress and responses in reciting and upholding Tantras. Though it is the basic requirement for any Tantric practitioner, it is not easy to breakthrough, because he can come across different physical and psychological reactions. Thus, the guidance of a qualified and experienced Guru master is absolutely necessary, otherwise he may get into 'trouble' and enter a deviant way in the pursuit of Buddhahood.

Tantric initiation and the Three 'Kayas'

The Tantric initiation is correlated with body, speech and mind, the basic division of human beings in Buddhsim. In Vajrayana, the attainment of Enlightenment is interpreted as the acquisition of the Three Kayas. Kaya literally means body. The Three Kayas represent different facets of the Enlightened Mind, different aspects of Buddhahood as it appears on three levels.

- Nirmanakaya (Form Body) -- Buddhahood as it appears on the human historical plane, i.e. Sakyamuni Buddha with his physical body, known as manifested personality, or body that can be seen with our human eyes.

- Sambhogakaya (Enjoyment Body) -- Buddhahood as it appears on higher archetypal plane, above and beyond the historical context, known as the body of reciprocal enjoyment, or the glorious personality, which can only be visualized by the Arhats or Bodhisattvas.

- Dharmakaya (Dharma Body) -- Buddhahood in its ultimate essence, known as absolute personality, which can be visualized by the Buddhas.

The Three Kayas also represent the body, speech and the mind of the Buddha. The aim of Vajrayana is to transform our body, speech and mind into the threefold personality of a Buddha. Our physical body is transformed into the Nirmanakaya of a Buddha with the aid of the 'Jar' Wong and its associated meditations. Our speech is transformed into the Sambhogakaya with the aid of the 'Secret' Wong. Our mind is transformed into Dharmakaya with the aid of 'Prajna' Wong. The fourth Wong represents the transformation of body, speech and mind collectively into Svabhavikakaya, which means the 'self-existent personality'. It is not really a body, but the totality of the other three.

Tantric Initiation and the Four Tantras

The four kinds of Tantric initiations are also correlated with the Four Sets of Tantras, or the Four Yogas (not the four Mula Yogas), but quite different Yogas sometimes known as the 'Four Tantras'. The practitioner attempts to transform his own body, speech and mind into an enlightened state by using the visualized deity as a model, and to realize the nature of emptiness at the same time.

- Kriyayoga, the ritual Tantra, also known as Action Tantra, which covers a whole class of practices, hundreds of different exercises. It is also known as Action Tantra. Primarily, it involves external rituals such as making offerings to the deities of Vajrayana, ritual bathing (taking refuge, like baptizing), symbolic hand gestures (hand seal, i.e. Mudras) and practices on pure conducts. Kriyayoga practices is usually described as consisting of one part meditation and three parts symbolic ritual. If a Tantric practice consists of, for example, a quarter of an hour's meditation and three-quarters of an hour's ritual, then it would be regarded as belonging to the Kriyayoga.

- Upayayoga, which means 'both sides' Tantra. It is also known as Charya Tantra or Performance Tantra. The practitioner engages in both internal and external practices and generates himself as a living embodiment of the deity. Upayayoga practices involve more meditation: half symbolic meditation and half ritual.

- Yoga Tantra, which consists of three parts meditation and one part symbolic ritual. The practitioner is required to take the Tantric vows, not just the Bodhisattva vows. At this stage, internal practices are emphasized to develop meditative stabilization.

- Anuttara Yoga, the Unsurpassed Yoga or Highest Yoga Tantra which, according to the traditional schema, is devoted solely to meditation. In deep concentratione practitioner generates higher insight on an image of the deity with the details of everyday reality and he transforms himself into the image. The Dharma Body is achieved through the wisdom (Prajna) that perceives emptiness, and the Enjoyment Body and Form Body through Deity Yoga. The supreme ones, providing many extraordinary subtle means of acquiring realization which are not found in the other Tantra sets, and emphasizing the techniques of the development and completion stages towards Buddhahood.

The first three Yogas are known as Outer Tantra or Exoteric Tantra, and the Anuttara Yoga comprises the Inner Tantra or Esoteric Tantra. These four initiations are collectively known as the 'Great Wong' or the 'Great Tantric Initiation'.

There are numerous systems of meditations (Sadhana) in each of the four sets of Tantras. Many of them lead to the acquisition of the so-called 'mundane Siddhis' (powers) such as long life, prosperity and pacification of harmful effect (Karmic force). However, it is said that only the Anuttara Tantra lead to the ultimate Sidhi, i.e. Mahamudra, known as the Great Seal in this very lifetime. With this power of primordial wisdom, one can achieve enlightenment.

More about Anuttara Tantra

The two principal phases in Anuttara Tantras are: namely, the development stage or generation stage and the completion stage, The former focuses upon luminosity while the latter upon emptiness.

Moreover, there are also numerous Anuttara Tantra deities. Among those who mostly worshipped are Hevajra, Chakrasamvara and the goddess Vajrayogini.

I general, there are four types of initiation in Anuttara Tantra:

- Vase initiation, Jar Wong, or Kalasa Ahbiseka -- it enables a practitioner to practice the generation stage.

- Secret initiation, Esoteric Wong, or Guhya Ahbiseka -- it allows the practitioner to practise developing the subtle body through energy and channel, etc.

- Wisdom initiation, Prajna Wong or Jnana-Prajna Ahbiseka -- it allows the practitioner to meditate on the innate mind of clear light.

- Word initiation -- it enables meditating practices on the union of the bliss and emptiness. Usually a word known as 'seed syllable' is given to the practitioner, which can purify his 8th, or Alaya consciousness in order to practise the Dzogchen.

Channel, Wind and Drop

For Tantric Buddhism, the universe is identical with the Buddha - all its dimensions and qualities consist of Buddha's manifestations and becoming a Buddha thus means merging with the universe. It can be achieved through analytical study and intellectual meditation. However, the meditation in traditional Buddhism is obviously different from that in Tantric Buddhism. According to the Highest Yoga Tantra, our body and mind exist not only on the gross level (physical form), but also on subtle level, the so-called Vajra body, having the connotation of indestructible. However, the former is composed of various material elements, and is subject to the inevitable sufferings of sickness, decay and death.

Just like that the physical body is pervaded by ordinary nervous system, the subtle Vajra body is pervaded by thousands of channels (Nadi in Sanskrit, Tsa in Tibetan) through which the subtle energy winds (Prana in Sanskrit, Lung in Tibetan) and drops ( Bindu in Sanskrit, Tigle in Tibetan) that are the source of the bliss so vital to the Highest Tantric practice. Most people are not aware of the subtle conscious body, but the Tantric practitioner can discover and make use of it.

The most important channel is the central one called 'central channel', which runs in a straight line from the crown of our head down to an area in front of our spine, and along several focal points known as Chakras, or energy wheels. Each one serves a different function in the practice of Tantra. The most important Chakra is the one located at the level of the heart, because the heart Chakra is the home of our very subtle mind, This very subtle mind has been with us from conception, for lifetimes without beginning. As the fundamental consciousness abiding at our heart center throughout this life, the very subtle mind is sometimes referred to as our Residential Mind. It is actually our original, fundamental Nature, which can only be realized upon awakening.

In Vajrayana, it is said that subtle channels are the body of awakening, subtle winds are the speech of awakening and the drops are the awakened mind. From the point of view of Buddhahood, the channels are the body of emanation, the winds are the body of perfect experience, and the drops are the absolute body.

By cultivating a profound concentration on the Vajra body in general and upon the central channel in particular, they are able to cut through the gross levels of mental functioning and make contact with their original Residential Mind. Making use of this Mind, they can meditate on the emptiness of self-existence and penetrate the ultimate nature of reality, thereby freeing themselves of all delusions. At the same time that this totally absorbed into an explosion of incredible blissful energy. The unity of great bliss and the simultaneous comprehension of emptiness (known as Mahamudra) is the quickest path towards perfect and complete enlightenment.

Practices for Developing Compassion

Compassion and wisdom are the two pillars in the support of Buddhism. In Tibetan Buddhism, the practices for developing compassion are plentiful. Compassion can emerge spontaneously, but it is usually borne from an understanding of the interdependent and impermanent nature of reality. There are some practices aimed at inspiring feelings of compassion. For instance, 'The Eight Verses on Thought Training' by the Kadampa master, Langri Thangpa. The practitioners have to contemplate and meditate on compassion as follows:

1. Seeing others as the foundation for the our practice

By thinking of all sentient beings

As even better than the wish-granting gems

For accomplishing the highest aim

May I always consider them precious

2. Seeing the needs of others as supreme

Wherever I go, with whomever I go,

May I see myself as less than all others,

And from the depth of my heart

May I consider them supremely precious.

3. Preventing delusions

May I examine my mind in all actions

And as soon as a negative state occurs,

Since it endangers myself and others,

May I firmly face and avert it.

4. Holding difficult people as dear

When I see beings of a negative disposition

Or those oppressed by negativity or pain,

May I, as if finding a treasure,

Consider them precious, for they are rarely met.

5. Accepting defeat

Whenever others, due to their jealousy,

Revile and treat me in unjust ways,

May I accept this defeat myself,

And offer the victory to others.

6. Regarding those who harm us as teachers

When someone whom I have helped

Or in whom I have placed great hope

Harms me with great injustice,

May I see that one as a sacred friend.

7. Exchange of self with others

In short, may I offer both directly and indirectly

All joy and benefit to all beings, my mothers,

And may I myself secretly take on

All of their hurt and suffering.

8. Seeing all things as illusion

May they not be defiled by the concepts

Of the eight worldly concerns

And are that all things are illusory

May they, ungrasping, be free from bondage.

Tonglen

Tonglen is a meditation practice to develop Bodhicitta in Tibetan Buddhism. Tonglen literally means 'Giving and Receiving'. It is also regarded as the Second Foundation Yoga or Mula Yoga. See section Special or Particular Preliminaries -- Four Mula Yogas.

The seventh verse of The Eight Verses on Thought Training is often referred in the practice of Tonglen. First, the practitioner is required to reflect on the equality of oneself and others, and to extend it to all beings in the six realms. One should then reflect upon the disadvantages of caring only for ourselves, and understand that selfishness is the cause of sufferings in our lives, thus developing a powerful sense of helping others. Moreover, one should reflect that this attitude is the source of happiness and the key to the door of Enlightenment.

Dzogchen (The Great Perfection)

According to the Nyingma tradition. the first transmission of Dozgchen was Garab Dorje, who received it from Buddha Vajrasattva in Oddyiyana. It passed on to Shir Singha, Jnanasutra, then Vimalamitra and Padmasambhava. The latter two formed two major lines of transmission of Dzogchen in Tibet.

Dzogchen is always described as a state of great perfection, the absolute fruition of the qualities of enlightenment, subsequent to a systematic order in teachings and practices. First of all, the teachings are divided into three series: the mind series, the space series and the instruction series. For the practices, it begins with Trek-cho, 'direct cutting', then proceeds with To-gal, 'leap over', just like 'Chi' and 'Kuan' in Tien Tai sect.

However, before one can start the practices of Dzogchen, one has to practice a series of preliminaries, which serves the pre-requisites in order to avoid spiritual chaos and conceit in the proper practices of Trek-cho and To-gal. The preliminaries consist of two parts.

The first part is the fourfold contemplation, often known as the Four Thoughts that Turn the Mind to Dharma, based on the teachings in the Sutras. It covers

- the understanding of rarity and preciousness of human birth in Dharma practice,

- urgency in practice because of impermanence and death,

- discriminating between good and evil by understanding the principle of cause and effect and Karma,

- renunciation to rid from Samsara.

The second part is the five meditations which are the inner practices based on the Sutras and Tantras. It covers

- taking refuge,

- developing Bodhicitta,

- meditating and reciting Vajrasattva,

- offering the Mandala,

- Guru yoga, i.e. receiving the blessings of the Lama and lineage.

In addition to the preliminaries, one might practice in Mahayoga utilizing the power of the eight deities, such as Vajrakilaya for assistance.

Once the preliminaries are well practiced, one can proceed to Trek-cho and To-gal. Trek-cho involves a transmission of awareness from a Vajrayana master. The practitioner is to cut all emotional disturbances, false thoughts, and even meditating experiences, and to bring directly to the underlying purity of awareness. Advancing to To-gal, one will utilize extremely esoteric methods to transform one's vision. For instance, the whole world is visualized as a Mandala, the residing place of the Buddhas. Those who achieve and master To-gal can obtain the Wisdom-body of a Buddha, a state of perfection.

Six Vajra Verses

The Six Vajra Verses explain the primordial condition of the individual, summing up the essence of the base (or fundamental perception), the path (or the methods to practice) and the fruit (or the effect and result as behavior) of Dzogchen. It is part of the teachings originally transmitted by Garab Dorje, containing the essential points of a number of Tantras. The Six Vajra Verses are as follows:

The nature of phenomena is non-dual,

But each one, in its own state, is beyond the limits of the mind.

There is no concept that can define the condition of 'what is'

But vision nevertheless manifests: all is good.

Everything has already been accomplished, and so, having overcome the sickness of effort,

One finds oneself in the self-perfected state: this is contemplation.

In the three parts of two lines each that make up the total of six lines, are to be found the principles of the base, the path, and the fruit, alongside a simultaneous explanation of the Way of seeing, the Way of practicing and the Way of behaving, according to the Dzogchen teachings.

Mahamudra

Mahamudra is the quintessential approach in the practice of Buddha Dharma, for which some understanding of the nature of mind is necessary. There are three aspects of Mahamudra:

- Foundation Mahamudra - it is the understanding based on the appreciation of the nature of mind

- Path Mahamudra - it is the direct experience and acclimatization to the nature of mind through meditation

- Fruition Mahamudra - it is the actualization of the potential inherent in the nature of mind.

A deeper understanding of the nature of the mind in Foundation Mahamudra can be achieved through the process of Path Mahamudra, until a thorough and complete stage of appreciation. The Fruition Mahamudra is the actualization of the transcendence in awareness with the Dharmakaya, Sambhogakaya and Nirmanakaya as the facets of completely enlightened experience.

The nature of the mind is that it is 'essentially empty', yet it is 'luminous potential to cognize' and 'unobstructed in dynamics'. In reality, it is indescribable in words. As a metaphor, the emptiness of mind is the ocean; the luminosity of mind is the sunlit ocean; and the unobstructed dynamic quality of mind is the waves of the sunlit ocean. The unity of the three aspects forms the seed or potential for enlightenment.

Commencing the practice of Foundation Mahamudra, the theoretical understanding of the Mahamudra approach is introduced or 'transmitted' by a qualified teacher. The practitioner then starts to apply the concept in his daily life, and verify with his own experience, which, though it is not the ultimate one. To directly experience the nature of the mind itself requires meditation and contemplation, and sometimes the so-called 'beyond meditation'.

Death and Dying

Death and dying is a popular topic in all Buddhist teachings, particularly Pure Land and Tibetan Buddhism. The Dalai Lama has said that his daily meditation involves preparation for death. Some Buddhists are encouraged to learn, analyze and even rehearse for the moment of death. As stipulated in the famous text 'The Tibetan Book of the Dead', there are several scenarios for the dying process. The practitioners have to be mentally and emotionally prepared at the time of dying, in order to reincarnate to the higher and better realms in the next rebirth. The process of dying is an opportunity for spiritual liberation if one's mind is calm without any pain and clinging.

Death should not be scared. It should be prepared seriously because a peaceful and supportive environment at the time of death is considered by Buddhists to be of utmost importance. The process of dying is an opportunity for spiritual liberation.

Stages of Death

It is described that the process of dying is divided into two stages, the outer dissolution of the sense powers and the inner dissolution of the mental states.

In the first stages, the Four Elements made up of our body dissolve.

Death is the separation of the mind (consciousness) from the body. This separation may take place over several hours or days. Generally, the body loses its ability to maintain consciousness gradually with each element of the body - earth, water, fire and air - losing its supportive ability in turn.

When one feels that the body becomes heavier and weaker, the dissolution of earth element commences. The water element dissolves when the body fluid is out of control. The dissolution of fire element is associated with the loss of body warmth. Difficulty in breathing is an indication that the air element is going to dissolve.

The inner dissolution begins with the manifestation of the 'ground luminosity' or 'clear light'. This is the revelation of one's own fundamental nature, which is also the fundamental nature of all phenomena. It is believed that one can be liberated right at this critical moment if one can recognize the clear light to be one's own mind-ground and unite with one's own life into a state of primordial purity. If one can recognize the clear light for what it really is, one will respond to it naturally as a child running into his mother's arms. If the clear light is not recognized, the mind enters the blackout state of Bardo.

Bardo

- See also: Bardo

By the time of dying, one's consciousness does not die with the body, but continues in subtle form in metaphysical dimensions called Bardo in Tibetan Buddhism. 'Bardo' means 'transition', or 'hanging in between' which can be compared to the soul in [[Wikipedia:Christianity|Christianity]]. (It should be noted that in general, Buddhists do not believe in an inherently existing and permanent soul.)

A temporal Bardo is a period of time, such as the period between sunset and sunrise. Bardos are the transitions of life, death and beyond, experienced by every being in Samsara, even insects. As outlined in The Tibetan Book of the Dead, there are six Bardos which span life, death and after death. In Tibetan Buddhism, the practitioner is encouraged to visualize all experiences in the Bardos after death as the projections of his own mind. But if he has not developed this ability in life, it will be almost impossible to do so when he dies.

When ordinary people die, they are out of control. It is said that however difficult it seems to calm the mind during life, it is much more difficult at the time of death. However, it is said that for those advanced practitioners who have trained their minds well, each stage of dissolution process brings ever increasing clarity and insight.

In Buddhism, the consciousness that continues from life to life is a subtle consciousness - the faculty of experiencing and being aware, the natural clarity of the mind. The fate of Bardo is largely determined by one's Karma, the effect of one's actions in past lives.

To tackle the problem of death, one has to know all things as mere appearances to the mind, like illusions. One should become familiar with what to expect when they die, so that one can deal with these illusions instead of being overwhelmed and confused by them.

Bardo States

- See also :

- See also :

There are three Bardo states:

- First Bardo state - It is the period of unconsciousness, which may last for 3 to 4 days.

- Second Bardo state - In this state, consciousness awakens, it unfolds like a flower exhibiting its natural radiance, which is experienced as color, light and sound. This 'energy' then coheres to form a 'Mandala' of deities, like Bodhisattva, etc. Once again, if one can recognize that the mind perceives the deities and the deities themselves are fundamentally the same, then 'liberation' can occur. If the mind still does not recognize itself, the consciousness then enters the phantasmagoric Bardo of becoming.

- Third Bardo state- It is the phantasmagoric Bardo of becoming. Here the mind takes on a mental body in a dimension where thoughts literally form one's reality. In this Bardo, the mind has the power of all the senses of the physical body, but with the ability to pass through solid objects, etc. Yet, in the Bardo of becoming, one is still merely an automation, 'programmed' by one's Karma in the past lives.

All kinds of visions and experiences that the Bardo has, can only last up to 49 days. It is a Buddhist tradition to pray for the deceased during this period, hoping that the benefits of such practices would reach the deceased during this period.

Phowa

Phowa is a kind of meditation practice involving 'transforming' one's mind into an enlightened one, such as the popular Amitabha Buddha, at the moment of death. It is quite similar to that of the Pure Land sect. By invoking or reciting the name of Amitabha Buddha, one enters into a meditative state of merging one's mind with that of the Buddha or one visualizes the Buddha in front. One then repents and requests for a peaceful death that will benefit other beings. One will be purified by the light rays emitted by the Buddha. Finally, the dying person dissolves into light and merges with the essence of the enlightened Buddha.

However, the full Phowa practice is a much more complicated ritual activity, which should be done only by a qualified master. A simplified version of this practice can be done for someone who is dying or even for a person who has already passed away. It can also be done for oneself.

Source

Buddhistdoor.com-Tibetan Buddhism I

Buddhistdoor.com-Tibetan Buddhism II

Buddhistdoor.com-Tibetan Buddhism III

Buddhistdoor.com-Tibetan Buddhism IV

Buddhistdoor.com-Tibetan Buddhism V

Buddhistdoor.com-Tibetan Buddhism VI

Buddhistdoor.com-Tibetan Buddhism VII