Mahayana Mahaparinirvana Sutra: Chapter 25: On Kaundinya

Mahayana Mahaparinirvana Sutra

Chapter 25: On Kaundinya

Translated by Kosho Yamamoto from Dharmakshema's Chinese version,

edited and revised by Dr. Tony Page

Copyright for this edition is held by Dr. Tony Page, 2012.

Then the World-Honoured One spoke to Kaundinya: "Material form is non-eternal. By doing away with this form, one arrives at the Eternal form of Emancipation. So does it obtain with feeling, perception, volition, and consciousness, too. By doing away with consciousness, one arrives at the Eternal form of Emancipation and Peace. This also pertains to feeling, perception, volition, and consciousness.

"O Kaundinya! Form is Void. By doing away with the form that is All-Void, one arrives at the Non-Void form of Emancipation. So does it obtain also with feeling, perception, volition, and consciousness.

“"O Kaundinya! Material form (“rupa”) is non-Self. By doing away with such form, one arrives at the form of the True Self of Emancipation. Feeling is non-Self. By doing away with such feeling, one arrives at the feeling of the True Self of Emancipation. Perception is non-Self. By doing away with such perception, one arrives at the perception of the True Self of Emancipation. Volition is non-Self. By doing away with such volition, one arrives at the volition of the True Self of Emancipation. Consciousness is non-Self. By doing away with such consciousness, one arrives at the consciousness of the True Self of Emancipation."

"O Kaundinya! Form is the non-Pure. By doing away with this form, one arrives at the Pure Form of Emancipation. So does it obtain also with feeling, perception, volition, and consciousness.

"O Kaundinya! Form is what represents birth, old age, illness, and death. By doing away with such form, one arrives at the form of the non-birth, non-old-age, non-illness, and non-death form of Emancipation. So does it also obtain with feeling, perception, volition, and consciousness.

"O Kaundinya! Form is the cause of ignorance. By doing away with such form, one arrives at the form of the non-cause of ignorance (characteristic) of Emancipation. So does it also obtain with feeling, perception, volition, and consciousness.

"O Kaundinya! Or form is the cause of birth even. By doing away with such form, one arrives at the form of the non-birth cause of Emancipation. So does it also obtain with feeling, perception, volition, and consciousness.

"O Kaundinya! Form is the cause of the four inversions. By doing away with inverted form, one arrives at the form of the four non-inverted causes of Emancipation. So does it also obtain with feeling, perception, volition, and consciousness.

"O Kaundinya! Physical form is the cause of innumerable evil things. It is the carnal body of the male, etc. It is the love of the food of lust. It is greed, anger, and jealousy. It is an evil and a grudging mind. It is ordinary food (i.e. food that has flavour, taste, and touch, and which can be cut and eaten), consciousness food (i.e. consciousness serving as food. For example, the mental power that at times checks one's sense of hunger), thought food (i.e. the power of thinking, or the volitional power), and touch food (i.e. the emotional sense that at times serves to check one's sense of hunger). There is egg-birth, embryo-birth, and transformed birth. There are the five desires and the five overshadowings. All of these are grounded on material form.

"By doing away with form, one arrives at the form of Emancipation, which does not contain any such evil things. It is the same with feeling, perception, volition, and consciousness.

"O Kaundinya! Form is bondage. By doing away with the form of bondage, one arrives at the form of Emancipation, which is no bondage. It is the same with feeling, perception, volition, and consciousness.

"O Kaundinya! Form is a stream. By doing away with the form which is a stream, one arrives at the form of Emancipation, which is not a stream. So is it also with feeling, perception, volition, and consciousness.

"O Kaundinya! Form is non-taking-of-refuge. By doing away with form, one arrives at the form of Emancipation, which is the taking of refuge. The same also applies to feeling, perception, volition, and consciousness.

"O Kaundinya! Form is the pox and warts. By doing away with form, one arrives at Emancipation, which is not the pox or warts. The same applies to feeling, perception, volition, and consciousness, too.

"O Kaundinya! Form is non-quietude. By doing away with this form, one arrives at the form of quietude of Nirvana, which is quiet. So does it also obtain with feeling, perception, volition, and consciousness.

"O Kaundinya! If there is any person who can so know things, such a person is a sramana or a Brahmin, and such a one is perfect in the Dharma of the sramana or Brahmin. O Kaundinya! If one parts from Buddha-Dharma, then one is no sramana or Brahmin; nor is there any Dharma of the sramana or Brahmin. All tirthikas speak falsely and cheat. And there is no action that is true (with them). Also, they pretend to say that there are such two. But this is not true. Why not? If there is no Dharma of the sramana or Brahmin, how can one say that here is a sramana or Brahmin? I always give a lion's roar amidst the congregation. You, too, should do the same amidst this congregation."

At that time, many tirthikas were present, who, on hearing this, became angry and said: "Gautama now says that there are no sramanas and Brahmins among us, and that there exists no Dharma of the sramana or Brahmin. What means shall we extensively adopt and address Gautama, to tell him that we too have sramanas and the Dharma of sramanas, and Brahmins and the Dharma of Brahmins?"

Then, there was amongst the crowd a Brahmacarin who said: "O all of you! What Gautama says is a thing of madness. There is no difference. What worth is there in taking up this point and worrying about it? All mad people sing, dance, weep, laugh, reprove, and praise. They cannot distinguish between enemies and friends. It is the same with Gautama, who says that he was born in the house of Suddhodana, or that he was not; or that when born, he took seven steps, or not; or that from his childhood he learnt the things of the world, or that he is the All-Knower; or that, at one time, he lived a palatial life, tasted (all) the pleasures and had a son, or that, at another time, he despised and reproved and reviled (sensual pleasures); or that he, at times, practised penance for six years, or that he condemned the penances of the tirthikas; or that he followed Udrakaramaputra and Aradakalama and was taught what he did not know before, or that there is nothing that he does not know; or that he attained unsurpassed Bodhi (Enlightenment) under the shade of the Bodhi Tree, or that he did not go to the tree, and that he did nothing; or that Nirvana comes when the fleshly body has gone. What Gautama says is what a mad man says, there is no difference. So why should we need to trouble ourselves over it?"

All the Brahmins answered and said: "O great one! How can we not but be troubled? Sramana Gautama renounced the world and said that what there was was nothing but the non-eternal, suffering, Void, non-Self, and the Impure, and our disciples heard his words and became frightened. How could we beings be non-eternal, suffering, Void, non-Self, and impure? We do not give ear to him. Now, Gautama is here again now, in this sal forest, and tells people that there is the Dharma of the Eternal, Bliss, the Self, and the Pure. All of my disciples hear his words, leave me and listen to Gautama's words. For this reason, I am greatly worried."

Then there was a Brahmin who said: "All of you! Listen carefully to me, listen carefully to me! Gautama professes to practise compassion. This is a lie. It is not true. If he has compassion, how can he teach my disciples and make them take to his teaching? The fruition of compassion is to follow the will of others. He is going against my wishes. How can we say that he has compassion? If Gautama says that he is not tainted by the eight things of the world, this again is nothing but falsehood. If it is said that Gautama desires little and that he is satisfied with what little he has, how, again, can he deprive us of what is ours? If he says that he is born of a high caste, this again is untrue. Why? Since of old, we have not seen or heard of a great lion-king who has ever caused harm to little rats. If Gautama is of high caste, how can he cause worry to us? If people say that Gautama possesses great power, this is a lie. Why? Since of old, we have never seen a garuda quarrelling with a cow. If he possesses great power, why would he quarrel with us? If it is said that Gautama possesses the power of reading people's minds, this again is a lie. Why so? If he is armed with this knowledge, how is it that he is dark in reading our minds? All of you! Once upon a time, I was with an aged and wise man who said that in 100 years' time, there would appear an apparition. This could well be Gautama. And such an apparition is now about to pass away in this forest of sal trees before long. Do not be worried!"

Then, there was a Nirgrantha, who said: "O you brothers! My mind is pained. This is not from the offerings of my disciples. The trouble is that the world is ignorant and eyeless and does not know what is a field of blessings and what is not. For they make offerings to one young, forsaking the aged and wise Brahmins. This is what worries me. Sramana Gautama knows much of sorcery. By this means, he presents one body in numerous forms and numerous forms in one, or he presents himself as a man, woman, cow, sheep, elephant, or horse. I will destroy such sorcery. When Sramana Gautama is gone, you will again enjoy many offerings and be blessed with peace."

Then there was a Brahmin who said: "Sramana Gautama is accomplished and perfect in innumerable virtues. So, you should not fight against him."

The great crowd said: "O you ignorant one! How dare you say that Sramana Gautama is accomplished in great virtue. Seven days after his birth, his mother died. Is that what you call a family of great blessings?"

The Brahmin said: "When reproached, one does not become angry, and when beaten, one does not strike back. Know that this can be none other than the form of great weal. His body is perfect in the 32 signs of perfection and the 80 minor marks of excellence and is armed with innumerable miraculous powers. So you must know that these are all of weal. His mind knows no arrogance. His mind first asks and reflects. What is said is gently spoken. There is no coarseness from the very start. His age and will are both rigorous, yet his mind is not rude. He does not covet any kingdom or wealth. He has abandoned all that, as one would tears and spit. That is why I say that Sramana Gautama is accomplished in innumerable virtues."

The great crowd said: "Well said! Sramana Gautama is, as you say, truly perfect in innumerable miraculous powers. How can I not fight with him against this? Sramana Gautama is gentle in feeling and nature. So he cannnot endure penance. Born in the depths of the palace, he is unable to master things. All he does is talk in a low voice. He knows no art, nothing of books and discussion. Let us talk about the essentials of Right Dharma. If he defeats me, I shall serve him; if I win, he serves me."

At that time, there were many tirthikas (present). Gathering together, they went to Magadha, to Ajatasatru. The king saw them and asked: "You are all in the holy teaching. You are those who have renounced the world. You have abandoned wealth and things of the secular life. The people of my land make all offerings to you. They look up to you with respect and do not act against you. Why do you band together and come here in one body and wish to see me? O you! You all belong to different teachings and have different precepts and different circumstances in which you renounced your homes. You each practise the Way following precepts. Why is it that you are all of one mind, as though the wind had driven the fallen leaves all together into one place? What do you intend to speak about by coming here “en masse”? I always protect world-fleeing people (i.e. spiritual questers, renunciates) and am not lagging much behind others in using my body and life (to help them)."

Then all the tirthikas said with one voice: "O great King! Listen to us carefully. You are now the great bridge of Dharma, the great horn, the great scales of Dharma. You are the utensil of all laws. You are the true nature of all virtues. You are the highway of Right Dharma. You are the last field wherein to sow seed. You are the fountainhead of the state. You are the bright mirror of all lands. You are all the forms of all heavens. You are the parent to the people of all lands. O great King! You are the treasure-house of all the virtues of the world. This is the King's body. Why do we say that you are the storehouse of virtue? The King carries on the administration of the state with no thought of partiality or hostility. The King's mind is fair like the earth, water, fire, and wind. That is why we say that the King is the storehouse of virtue.

"O great King! The life span of beings in the present age is paltry. But the virtue of the King is like that of kings from days gone by, when man was blessed with long life and peace. The situation is like that of Head-Born, Sudarsana, Forbearance, Nahusa, Yajata, Sibi, and Iksvaku. All such kings were perfect in the Good Dharma. You too, King, are the same. O great King! Due to you, the land is at peace and the people are doing well. That is why all the world-fleeing love this state and uphold the precepts, make effort, and practise the right way. O great King! I state in my sutras that if the world-fleeing observe the precepts and make effort as set forth in the state, the King also shares in the good which is practised. O great King! You have already made away with all robbers, and there is nothing for the world-fleeing to be afraid of. Only, there lives just one evil person - Sramana Gautama. You, King, have not yet tested him. We are all afraid. This person sits on (prides himself on) his high birth and caste and on his bodily accomplishment, and by dint of the past danas he has performed, he is recompensed with many offerings. In all such circumstances, he is arrogant, and because of his sorcery, he is haughty. For this reason, we cannot carry out our penances. He receives soft clothes and bedding. Thus, he is the most evil in all the world. For profit, people go to him, and on becoming members of his hosuehold, they are unable to practise penance. Through sorcery, he vanquished Kasyapa, Sariputra, Maudgalyayana, and others. And now he has come to our place, to the forest of sal trees, and, declaring that this body is the Eternal, Bliss, Self, and the Pure, he lures away our disciples. O great King! Previously Gautama said: non-eternal, non-bliss, non-Self, and non-pure. I well forbore it. Now he says: Eternal, Bliss, Self, and Pure. I cannot stand it. Please, O great King! Allow me to argue the point with Gautama."

The king said: "All you great ones! What has stirred you up, so that you now become mad and unsettled like great waves of water, or like circles of flame, or like monkeys who throw themselves across the trees? This is a shame. If the wise hear of this, they will pity you. If the ignorant hear of this, they will laugh at you. What you say is not appropriate for any world-fleeing person. If you are suffering from the illness of wind or from the yellow-water pox, I have medicine for all of this. I shall cure you. If it comes from any illness of a devil, my family man (family doctor), Jivaka (a famous doctor in the royal household of Ajatasatru), will thoroughly do away with it. All of you now intend to srape Mount Sumeru with your hands and nails, or to try to chew and gnaw on a diamond.

"O all of you great ones! This is like an ignorant person wanting to awaken a sleeping lion-king at a time when the lion is feeling hungry; or like trying to touch the mouth of a viper with one's finger; or like playing with the embers that lie under the ashes. This is the situation with you now. This is like a wild fox wishing to imitate a lion's roar, or a mosquito competing in speed with a garuda (swift, mythical bird). It is like a hare desiring to cross the sea and plumb its depths. You, too, are now like this. If you are dreaming of a victory over Gautama, such a dream is one that is fanatical (fantastical). It is not worth believing in. O you great ones! You now think thus. This is like a flying moth that throws itself into a fire ball. Take my word! Do not say any more! You say that I am fair and am like a pair of scales. But do not let anything like this reach the ears of other persons."

Then the tirthikas said: "O great King! The sorcery of Gautama will be such that, when it appears before you, it will make the mind of the great King not doubt the words of these holy ones. O great King! Please do not despise the great ones. O great King! Who gave the knowledge of the waxing and waning of the moon, the saltiness of the water of the great sea, and of Mount Malaya? Is all this not the work of the Brahmins? O great King! Did you not hear that the rishi, Gautama, performed a miracle, so that for 12 long years he transformed himself into the carnal body of the Sakya, and made the body of the Sakya like that of a ram and made 1,000 valvas which were made to remain in the body of the Sakya? O great King! Have you not heard that the sishi, Jatukarna, drank in one day the waters of the four seas, so that the earth all became dry? O great King! Have you not heard that the rishi, Vasu, became a Mahesvara and had three eyes? O great King! Have you not heard that the rishi, Aradakalama, changed Garapu Castle into earth? O great King! The Brahmins have such men of great power. You can easily check the facts. O great King! Why do you so belittle them?"

The king said: "All of you! If you do not believe what I tell you, the Tathagata, the Right-Enlightened one, is now in the forest of sal trees. You may go and question or reprove him as you will. The Tathagata too will see you and for your sake will explain things in detail and answer your questions."

Then King Ajatasatru went to the Buddha, together with the tirthikas and with his own retinue. He prostrated himself on the ground, and walked around the Buddha three times. Having paid his homage, he drew back and took his seat on one side and said to the Buddha: "These tirthikas desire to put questions to you in their own way. Will you be so good as to answer them?"

The Buddha said: "O great King! Wait! I know when I must."

Then, amongst those who were present, there was a Brahmin, Jataishuna by name. He said: "O Gautama! Do you state that Nirvana is that which is eternal?"

"It is thus, it is thus, O great Brahmin!"

The Brahmin said: "You say that Nirvana is eternal. But this is not the case. Why not? What obtains in the world is that from a seed comes about the fruit. This continues, and there is no disruption. This is as with a pot, which comes about from the earth and from thread cloth. You, Gautama, always say: "When one practises the image of the non-eternal, one arrives at Nirvana." You also say, Gautama: "When one makes away with desire and greed, this is Nirvana. When one does away with the greed of the body (“rupa”) and non-body, this is Nirvana. When one has made away with the defilement of ignorance, this is Nirvana." All that goes from desire up to the defilement of ignorance is non-eternal. If the cause is non-eternal, the Nirvana that comes about (from it) must also be non-eternal. You, Gautama, also say: "Through cause comes about birth in heaven; through cause one gains hell, and through cause emancipation. Thus, all things come about from causes." If Emancipation results from a cause, how can one call it eternal?

"Also you, Gautama, say: "Form (“rupa”) comes about from causal relations. Hence, non-eternal. So is it also with feeling, perception, volition, and consciousness." If Emancipation is form, know that what there is (here) is non-eternal. So does it also stand with feeling, perception, volition, and consciousness. If there is any Emancipation away from the five skandhas, that Emancipation is Void. If it is Void, we cannot say that things come from causal relations. Why not? Because eternity is one and pervades everywhere. You, Gautama, also say that what comes about from causation is suffering. If it is suffering, how can we say that Emancipation is Bliss?

"O Gautama! And you say that the non-eternal is suffering and that suffering is non-Self. If non-eternal, suffering, and non-Self, what there is is the non-pure. What does not come from cause must be non-eternal, suffering, non-Self, and non-pure. How can we say that Nirvana is the Eternal, Bliss, the Self, and the Pure? O Gautama! If one states: eternal and non-eternal, suffering and bliss, the Self and the non-Self, pure and non-pure - are these not two terms? I once heard from the aged and wise that: "If any Buddha appears in the world, he does not speak any double words." You Gautama now speak of two words and say: "And the Buddha is my own carnal self." What do you mean by this?"

The Buddha said: "O Brahmin! I shall now ask you about what you say. Answer just as you think!"

The Brahmin said: "Well said, Gautama!"

The Buddha said: "Is your nature eternal or non-eternal?"

The Brahmin said: "My nature is eternal."

"O Brahmin! Does this nature become a cause of things within and without?"

"That is so, Gautama."

The Buddha said: "O Brahmin! How does it become the cause?"

"O Gautama! From nature comes about "great"; from great, arrogance; from arrogance, 16 things, which are: 1) earth, water, fire, wind, and space; 2) the five sense-organs, which are: eye, ear, nose, tongue, and touch; 3) the five acting organs, which are: hand, foot, voice, the two sexual organs of male and female; 4) the all-equal sense-organs of mind. These 16 things come about from five things, which are: colour, sound, smell, taste, and touch. These 21 things have three root qualities, which are: 1) defiling, 2) coarse, and 3) black. The defiling is craving; the coarse is anger; and black is ignorance. O Gautama! These 25 things come about from nature."

"O Brahmin! Are these things that are great, etc., eternal or non-eternal?"

"O Gautama! The dharma nature that I speak about is eternal. All things, beginning with "great", are non-eternal."

"O Brahmin! From what you say, it seems that according to you the cause is eternal and the fruit non-eternal. Now, what wrong could there be when I say that the cause is non-eternal, but the result is eternal? O Brahmin! Are there two causes in what you speak of?"

The reply came back: "Yes! There are."

The Buddha said: "What are the two?"

The Brahmin said: "One is cause by birth and the other is the revealing cause."

The Buddha said: What is cause by birth and what the revealing cause?"

The Brahmin said: "The cause by birth may be likened to the earth from which comes about a pot; the revealing cause is like a lamp that shines upon a thing."

The Buddha said: "Of these two kinds of cause, is the nature of the cause one? If it is one, cause by birth may well turn out to be the revealing cause, and the revealing cause may turn into cause by birth. Is this not so?"

"No, O Gautama!"

The Buddha said: "I say that Nirvana is attained from the non-eternal, but it is not non-eternal. O Brahmin! When we gain it through the revealing cause, we gain the Eternal, Bliss, the Self, and the Pure. When we see it from the standpoint of cause by birth, we gain the non-eternal, non-birth, non-Self, and non-Pure. That is why the Tathagata speaks in two ways. There can be no such two words. That is why we say that the Tathagata does not have two words. You say that you once heard from wise people who are now gone that: "The Buddha appears in the world and he does not speak any two words." This is all very well. What is said by all Buddhas of the ten directions and of the Three Times does not differ. That is why we say that the Buddha does not have any two words (i.e. differing statements).

"How do they not differ? What is "is" is declared as "is"; whatever is "is-not" is stated to be "is-not". Hence, one meaning. O Brahmin! The Tathagata-World-Honoured One says two things. This is but to reveal one word. How do two words come to reveal one? It is as in the case of the two words of "eye" and "form", which call forth the one word of "living consciousness". So does it obtain with mind and dharma."

The Brahmin said: "O Gautama! You well grasp the meanings of such words. I do not yet gain the meaning that two words are one."

Then the World-Honoured One spoke of the Four Truths. "O Brahmin! We speak of the "Truth of Suffering", which is two and also one. This applies all the way down to the Truth of the Way, which again is two and also one."

The Brahmin said: "O World-Honoured One! I now see."

The Buddha said: "In what way do you see?"

"O World-Honoured One! We say "Truth of Suffering". All common mortals see two things. But with the holy persons, what there is is one. So is it with the Truth of the Way, too."

The Buddha said: "Well said! You see well."

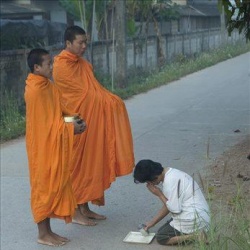

The Brahmin said: "O World-Honoured One! I have now heard Dharma and gained the right view. I shall now take refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. I pray that you will admit me into your Order."

Then the World-Honoured One said to Kaundinya: "You now shave this Jadaishuna and admit him into the Order."

Then Kaundinya, by order of the Buddha, shaved (Jadaishuna). When this was done, there were two fallings: one of hair, and the other of defilement. And at that instant, he attained arhatship.

Also, there was a Brahmacarin called Vasistha, who said: "O Gautama! Is the Nirvana you speak of eternal?"

"It is so, O Brahmacarin!"

Vasistha said: "O Gautama! When there is no defilement, do you not call this Nirvana?"

"It is thus, O Brahmacarin!"

Vasistha said: "There are four instances where we say "not-is". These are: 1) a thing which has not yet come about. This is a not-is. This is as in the case of a pot when it has not yet come out of the mud. And we say that there is no pot; 2) whatever has gone is called "not-is". This is as in the case of a broken pot. At such a time, we say that there is no pot; 3) whatever does not exist in things that are different in nature, when we say is-not, as in the case of a cow, in which there is nothing of a horse, and in that of a horse, in which there is no cow; 4) when nothing exists in any circumstances whatsoever, as in the case of the hair of a tortoise or the horns of a hare. O good man! If Nirvana is that which is when defilement is done away with, Nirvana is a "not-is". If so, how can we say that there are the Eternal, Bliss, the Self, and the Pure?"

The Buddha said: "O good man! Nirvana as such is not like a pot that did not exist when as yet in the mud. Also, it is not like the "not-is" of extinction, or the not-is of a pot that is broken. Also, it is not the not-is if the absolute not-is, as in the case of the hair of a tortoise or the horns of a hare; nor is it the not-is of that which is different by nature.

"O good man! You can say that there is no horse in a cow. But you cannot say: "There is no cow." There is no cow in a horse, but you cannot say: "There is no horse." So does it also obtain with Nirvana. There is no Nirvana in defilement, and no defilement in Nirvana. So, we say that different things do not mutually possess each other."

Vasistha said: "O Gautama! If you say that Nirvana is what does not exist in what is other, this will entail your saying that the Eternal, Bliss, Self, and the Pure do not exist in the noneness of a different thing. O Gautama! How can you say that there are the Eternal, Bliss, the Self, and the Pure?"

The Buddha said: "There are three nonenesses in what you say. The case of the cow and the horse is what was not before, but what is. This is what was not before. What was, but what is not (any longer), is what comes about when a thing breaks up. The non-is by way of difference is as you say. O good man! We do not find these three kinds of not-is in Nirvana. Therefore, Nirvana is the Eternal, Bliss, Self, and the Pure. This is as as with one who is ill, (where there is either): 1) fever, 2) illness from wind, or 3) cold. These can well be cured by the three kinds of medicine. A person suffering from fever can be well cured by butter; one suffering from wind can be cured by oil; and a person who is suffering from a cold can indeed be cured by honey. These three kinds of medicine can indeed cure the three kinds of evil illnesses. O good man! In wind, there is no oil, and in oil no wind; or in honey, there is no cold, and in the cold there is no honey. Therefore, a cure indeed results. It is the same with all beings, too. They have three illnesses, which are: 1) greed, 2) ill-will, and 3) ignorance. Three kinds of medicine will cure these three illnesses. Meditation upon impurity will act as a medicine against desire; that on loving-kindness will act as medicine against ill-will; that on the knowledge of causal relations will act against ignorance.

"O good man! In order to make away with desire, one meditates on non-desire; to make away with ill-will, the meditation upon non-ill-will is performed; to make away with ignorance, one meditates on non-ignorance. In the three illnesses we do not have the three kinds of medicine, and in the three kinds of medicine we do not have the three kinds of illness. O good man! As there are not the three kinds of medicine in the three kinds of illness, this is the non-eternal, non-Self, non-bliss, and non-pure. In the three kinds of medicine there are not the three types of illness. Hence, the Eternal, Bliss, the Self, and the Pure."

Vasistha said: "O World-Honoured One! You, the Tathagata, explain to me about the eternal and the non-eternal. What is the eternal, and what is the non-eternal?"

The Buddha said: "O good man! Form is non-eternal, and emancipation from form is the Eternal. And consciousness is non-eternal, and emancipation from consciousness is the Eternal. O good man! If there is any good man or woman who can well see that form down to consciousness are non-eternal, know that such a person can well attain what is Eternal."

Vasistha said: "O World-Honoured One! I have now truly come to know the Eternal and the non-eternal."

The Buddha said: "O good man! How do you know the Eternal and the non-eternal?"

Vasistha said: "I now know that self and form are non-eternal and that Emancipation is Eternal. So is it with (the skandhas) down to consciousness."

"O good man! You now well repay to this carnal body what you owe." To Kaundinya, he said: "This Vasistha has now attained the fruition of arhatship. Give him the three clothes (robes) and a bowl."

Then Kaundinya gave the clothes as instructed by the Buddha. Then, on receiving the robes and bowl, Vasistha said: "O Kaundinya, greatly virtuous one! I have now gained upon this carnal body of mine a great karmic reward. Please, O greatly virtuous one, condescend to go to the Buddha and report in detail what has transpired with me. This evil body of mine has touched and defiled the Tathagata and now adopts his family name of Gautama. Please report on my behalf and say that I now repent of my evil self. I, also, cannot have this body of mine long in life. I shall now enter Nirvana."

Then Kaundinya went to the Buddha and said: "O World-Honoured One! The bhiksu Vasistha repents and says: "Obstinate fool that I was, I touched the body of the Tathagata and am now one of his group (following). I cannot have this viperous body of mine staying long in the world." He now desires to make away with this body and comes to me and repents."

The Buddha said: "O Kaundinya! Vasistha has long amassed virtue at the places of innumerable Buddhas. Having now been taught by me, he is rightly abiding in the Way. Abiding rightly in the Way, he has arrived at the right fruition. You should make offerings to his carnal self."

Kaundinya, thus directed by the Buddha, went to where the person lived and made offerings. Then, Vasistha, at the time of his cremation, performed many a divine miracle. All the tirthikas saw this and said aloud: "This Vasistha has acquired sorcery at the place of Sramana Gautama."

Then, at that time, there was among the group a Brahmacarin called Senika, who said: "O Gautama! Is there self?" The Tathagata was silent. He asked a second time, and a third time. The Buddha was silent. Senika said: "O Gautama! All beings possess self, which pervades everywhere, and the creator is one. O Gautama! Why do you sit silently and not answer?"

The Buddha said: "O Senika! Do you say that this self pervades everywhere?"

Senika answered and said: "It is not I alone who say so, but all the wise have also shown this."

The Buddha said: "O good man! If self pervades everywhere, all the beings of the five realms would have to gain the returns of actions performed at one (i.e. the same) time. If all the people of the five realms have (the same) karmic results, why do you avoid all evil actions, so as to evade hell, and do all good things, so as to gain life in heaven?"

Senika said: "O Gautama! There are two kinds of self of which I talk, namely: 1) the carnal self and 2) the eternal self. For the sake of the carnal self, we practise the Way and shun evil, so as not to gain hell, and practise all good deeds, so as to gain life in heaven."

The Buddha said: "O good man! You say that self pervades all places. It it is in the created self, you may know that such a self is non-eternal. If it is not created, how can you say that it pervades everywhere?"

"O Gautama! The self I speak of exists in what is created and yet is what is eternal. O Gautama! A person happens to cause a fire in the house. The master of the house comes out. So we cannot say: "When the house is reduced to ashes, the master of the house is also reduced to ashes." It is the same with what I say. This created body is non-eternal. But when the non-eternal is about to start out (i.e. when the body is about to die), the self goes out. So the self I speak of is all-pervading and eternal."

The Buddha said: "O good man! You say: "The self I speak of is all-pervading and eternal." But this is not so. Why not? Of what pervades, there are two kinds. These are: 1) eternal and 2) non-eternal. Again, there are two kinds, namely: 1) form and 2) non-form. Hence, when one says that all exists, this means that it is eternal and non-eternal; it is form and non-form. You may say that the master of the house is out of the house, and that there is no non-eternal to come about. But this is not so. Why? The house is no master and the master no house. That which is different is burnt and what is different is out. Thus goes the logic. The self is not anything as such. Why not? The self is form and form self. Non-form is self and self non-form. How can you say that when form suffers change, the self is out of it?

"O good man! You may say that all beings possess the same self. But this is contrary to what obtains in the secular or supramundane world. Why? What obtains in the secular world speaks of father and mother, boy and girl. If we are to say: "The self is one; the father is the son, the son the father; the mother is the girl, and the girl the mother; the enemy is the friend, and the friend the enemy; this is that and that this. Hence, all beings possess the same self" - this is counter to what obtains in the secular or the supramundane world."

Senika said: "I, too, do not say that all beings possess one self. I say that each person possesses one self."

The Buddha said: "O good man! If it is said that each person has one self, this means none other than that there are many selves. This is not so. Why not? You said before that self pervades. If self goes everywhere, the karmic root of all beings must be the same. When heaven sees, the Buddha sees; when heaven acts, the Buddha acts; when heaven hears, the Buddha hears. All things must be thus. If heaven can see and the Buddha cannot, we cannot say that self extends everywhere. If it is non-pervading, this is nothing other than the non-eternal."

Senika said: "O Gautama! The self of all beings pervades everywhere, whereas law (Dharma): (the following discussion on self is obscure in its details, and difficult to follow - ed.) and non-law do not. By this, the Buddha can act differently and heaven also can act thus. Hence, you, Gautama, should not say: "When the Buddha sees, heaven can see, and when the Buddha can hear, heaven can hear."

The Buddha said: "O good man! Is it not the case that law and non-law are what one does?"

Senika said: "Such are the works of one's actions."

The Buddha said: "If law (dharma, that which exists) and non-law are what one does, this means the same thing. How could they be different? Why? Where the Buddha gains action in hand, heaven gains the self; where heaven gains action in hand, the Buddha gains in hand the self. Hence, when the Buddha can do, heaven can do. Law and non-law must obtain thus. O good man! So, if the law and non-law of beings is thus, there cannot be any other different karmic results. O good man! From the seed comes about the fruit. This seed never thinks: "I shall become the fruit of a Brahmin, not that of a Kshatriya, Vaishya, or Sudra." Why? The seed carried forth the fruit. It concerns (i.e. is concerned with) no caste or anything as such. It is the same with law and non-law, too. We cannot discriminatingly think: "I shall only attain the fruition of Buddhahood, not of heaven; I shall only attain the fruition of heaven, but not of Buddhahood." Why not? Because karma works fairly."

Senika said: "O Gautama! For example, there are hundreds and thousands of lamps in a room. The wicks may differ, but the light does not differ. The fact that the wicks of the lamps differ can be compared to law and non-law, and the fact that there is no difference in the light can be compared to the self of beings."

The Buddha said: "O good man! You take up the case of the light of a lamp and mean (thereby) to explain self. This does not apply well. Why not? The room is different and the lamp is different. The light of the lamp goes around the wick and it also pervades the room. If the self you speak of is thus, self must lie around law and non-law. There must be law and non-law in self. If law and non-law do not exist in self, one cannot say: "It pervades all places." If it (they) go together, how can we employ the analogy of the light of the wick? O good man! If you truly mean to say that the wick and the light are different, why is it that when the number of wicks increases, the light becomes brighter, and when the wick is spent, the light, too, dies out? Hence, we can compare law and non-law to the wick and the light, and the non-difference of light to self. Why? Because the three - law, non-law, and self - are but one."

Senika said: "O Gautama! You take up the simile of the lamp. This is unfortunate. Why? If the simile of the lamp is good, I have already employed it before. If it is unfortunate, what more need is there to refer to it again?"

"O good man! I employ analogies. But these have nothing to do with what is fortunate or unfortunate. I accord with your will, and in the analogy I say that there is light away from the wick and that there is light along with the wick. Your mind is not fair. You purposely take up the case of the wick and the lamp and compare these to law and non-law, and liken the light to self. That is why I mean to reprove (you on this point). The wick is the light. Is there any light away from the wick? Dharma is at once (i.e. at the same time) the self; the self is at once Dharma. Non-Dharma is at once self and self at once non-Dharma. Now, you say: "Why does one take up one aspect and not take up the other?" But such a simile is unfortunate for you. That is why I crush you instead. O good man! Such an analogy does not work out (i.e. does not work well as) an analogy. Due to the fact that it does not constitute an analogy, it works favourably on my side and not on yours. O good man! You may think: "If it is unfortunate for me, is it not also so for you?" But this is not so. Why not? In the world we see a person who kills himself with his own sword; whatever is done by one's own hand is made use of by others. The analogy you employ works likewise. Luck is on my side and ill-luck on yours."

Senika said: "O Gautama! You reproved me before for the unfairness of my mind. Now, what you say is not fair either. Why not? O Gautama! You now direct (ascribe) luck to yourself and bad luck to me. From this, I conclude and see this unfairness."

The Buddha said: "What is not fair on my side truly breaks (destroys? evens out) what is not fair on your side. Because of this, what is fair with you and what is not on my side bespeak luck. What is not fair on my side breaks what is not on your side, and you harvest what is fair. This is the fairness on my side. Why? Because this calls forth what is fair on all holy persons."

Senika said: "O Gautama! Self is always fair. How can you say that you crush out the non-fair? All beings possess self all-equally. How can you say that self is not all-equal?"

"O good man! You too say that one gains birth in hell, one gains birth in the realm of hungry pretas, one gains birth in the animal realm, and one gains birth in the worlds of humans and gods. If self already pervades the five realms, can one say that one gains life in various realms? You also say that through the harmony (i.e. coming together) of parents, a child comes about. If there is a child beforehand, how can one say that through harmonisation a child comes about? Because of this, one possesses the body of the five realms. If it is the case that these five realms already precede the carnal existence of the body, how can one say that one enacts karma? Hence, unequal.

"O good man! You may mean to say that self is that which does. But this is not so. Why not? If self is that which does (i.e. performs actions), why should one do what is pain to oneself? But we actually see beings who are suffering from pain. Thus we may know that self is not that which does. If we are to say that this pain is not what is done (made) by self and that it does not come about from a cause, this must mean that all things, too, do not come about from a cause. On what grounds can you say that it is the doing of self?

"O good man! All the sufferings and happinesses of beings come about from causes and conditions. Thus, suffering and happiness call forth apprehension and joy. When one has apprehension, there is no joy; when there is joy, there is no apprehension. It is either joy or apprehension. How can any wise person call this eternal?

"O good man! You state that self is eternal. If it is eternal, how can you say that there are the differences of the ten times (i.e.the stages of growth of the human, from embryo to old age)? With the Eternal, there can never be any kalala (embryo) time, down to the days of old age. The permanent existence of the Void cannot have a single "time". How could there be the ten times?

"O good man! Self is no time of kalala or the days of old age. How can you say that there are the differences of the ten times? O good man! If self is something that does, there must be with this self the time of the prime of life and the days of old age. Beings, too, have this prime of life and the days of old age. If self is anything of this sort, how could it be eternal? O good man! If self is that which does, how could there be the differences of sharp and dull to one (i.e. how could there be mental sharpness and dullness amongst people)? O good man! If self is something that acts, this self can certainly perform bodily, oral and mental actions. If this is the work of self, how can one say that there is no self in the mouth? How can one doubt and wonder if it is "is" or "is-not"?

"O good man! You may say that there is seeing separate from the eye. But this is not so. Why not? If there is any seeing separate from the eye, what point is there in using the eyes? The same applies to the bodily sense-organs, too. You may say that self always sees with the eyes. But the case is not thus. Why not? This is like saying: "The Sumana bloom reduces a great village to ashes." How does it burn? It burns with fire. The same is the case when you say that self sees."

Senika said: "O Gautama! It is like the case of the sickle, with which one can cut grass. The same is the case with self, which can indeed see and hear and touch through the five sense-organs."

"O good man! The sickle and the man are different things. Because of this, a person can indeed take up the sickle and do things. Away from the sense-organs, there can be no self. How can one say: "Self can (act) with all the sense-organs?" O good man! If you mean to say that a person can indeed mow when he takes up a sickle, and the same is the case with self - does this self have a hand or not? It it does, why not take it (i.e. why does not self directly pick up the sickle, without the use of physical hands)? If self has no hands, how can we say that self is one that does? O good man! That which cuts the grass is the sickle. It is not self, nor is it man. If self or man can indeed cut, why does one need to depend upon any sickle?

"O good man! The man performs two actions, namely: 1) taking the grass and 2) using the sickle. The sickle can truly cut. The same is the case with beings. The eye indeed sees forms. This arises from harmonisation (conjoining of causes and conditions). If something is seen through the harmonisation of causal relations, how can the wise say that there is self? This is not so. Why not? In the world, we do not see that heaven performs actions and that the Buddha receives the fruit. If you mean to say that it is not that the body does but self receives without having enacted the cause, why should you hope to attain Emancipation through causal relations? If your body were to be born with no cause, after attaining Emancipation you would gain your body without any cause. Just as with the body, so all defilements, too, would thus come about."

Senika said: "O Gautama! There are two selves. One knows and the other knows not. The self that knows not truly gains the physical body and the self that abandons one's own self. This is as with an earthen pot, which, when treated in the oven, changes its colour and when there is nothing that is to come about again any more. It is also thus with the defilements of a wise person. There is no more coming about (of them)."

The Buddha said: "O good man! You speak of "knowing". Is it the intellect that knows or self that knows? If the intellect can know, why do we say that self knows? If self knows, why do we particularly work out means for knowing? If you mean to say that self knows through the intellect, this is as in the case of the analogy of the flower, which breaks and falls. O good man! This is as in the case of a tree that has thorns, which prick by nature. We cannot say that the tree takes the thorns and pricks. It is the same with the intellect too. The intellect knows by itself. How can we say that self takes the intellect and knows? O good man! You say in your teaching that self arrives at emancipation. Is it the non-intellectual self or the intellectual self which gains (this)? If it is the non-intellectual self which gains (this), we can know that it must still possess defilement. If it is the case that the intellect gains (Emancipation), we can know that there are already the five senses and sense-organs. Why? There cannot be any intellect other than the roots. If all the root organs are perfect, how can we say that the person arrives at Emancipation? If the nature of self is pure and is separate from the five roots, how can it pervade, and exist in, the five realms? Why does a person practise all good deeds to arrive at Emancipation?

"O good man! For example, it is (like) extracting thorns from the Void. Things go the same with you. If the self is pure, how can we say that a person cuts off all defilements? If you intend to say that the person arrives at Emancipation not being based on causal relations, why is it that all animals do not arrive at it?"

Senika said: "O Gautama! If it is selfless, whoever can remember well?"

The Buddha said to Senika: "If there is self, why do we forget? O good man! If remembering is self, why do we remember unhappy things, remember what we do not wish to remember, and not remember what we mean to remember?"

Senika said: "O Gautama! If there is no self, who sees and who hears?"

The Buddha said: "One has six spheres within and six dusts (i.e. the six sense-fields) without. The inner and outer conjoin and one gains the six kinds of consciousness. Now, these six consciousnesses gain their name through causal relations.

"For example, a fire comes about from a tree, and we speak of a "tree fire". Grass catches fire, and we speak of "grass fire". Bran catches fire, and we speak of "bran fire". Cow dung catches fire, and we speak of "cow-dung fire". It is the same thing with the consciousness of beings, too.

"We gain consciousness by means of the eyes, colour, light, and desire, and we say "eye-consciousness". O good man! Such eye-consciousness does not exist in the eye, nor in the desire, etc. The four things conjoin and we get this consciousness. It is the same with the consciousness of mind. If things come into being thus, we cannot say that knowing and seeing are self, and that touching is self.

"O good man! That is why we say that self is the eye-consciousness down to mental consciousness, and that all things are phantoms. How are they like phantoms? Because of the fact that what originally was not is what now is, and what once was is now no more. O good man! For example, the mixing together of butter, barley, flour, honey, ginger, pepper, pippali (a long pepper), grapes, walnuts, pomegranate, and suishi (a kind of prune) is called "kangigan" (possibly the name of a drug). Apart from this mixing together, there can be no kangigan. The six spheres of the inner and outer are what we call the being, self, man, or male. Other than the spheres within and without, there can be no being or man."

Senika said: "O Gautama! If selfless, why do we say: "I see", "I hear", "I have sorrow", "I feel bliss", "I have apprehension", or "I am glad"?

The Buddha said: "O good man! If we say "I see", "I hear", etc., this implies that there is a self. Why does the world say: "The sins of our deeds are not what I see or hear about?" O good man! The coming together of the four armies (i.e. the four constituent parts of an army) is termed an "army". These four are not one, but we say: "Our army is valiant, our army is superior to his." It is the same with what comes about through the conjoining together of the inner and outer spheres, too. Though they are not one, we say: "I do", "I feel", "I see", "I hear", "I have sorrow", "I feel bliss"'.

Senika said: "O Gautama! You speak of the "conjoining together of the inner and outer." Who is it that says: "I do", "I feel"?

The Buddha said: "O Senika! From the causal relations of the ignorance of craving comes about action, from it existence, from it the innumerable varieties of mental actions, and mental wakefulness in perception. This mental wakefulness in perception causes the wind to rise, and the wind, following the mind, touches the throat, tongue, teeth, and lips. The inverted voice of the image of the being comes out and says: "I do, I feel, I see, and I hear." O good man! The bell on top of a hanging ensign rings due to causal relations. If the wind is strong, the sound is strong; if the wind is weak, the sound is weak. And yet, no one does it. That is how matters stand. When a heated iron is put into water, this engenders various sounds. And yet, there is truly no one who does it (i.e. who makes those sounds). The case is thus. O good man! The common mortal is unable to think or discriminate such things and says: "There is self, and what belongs to self; I do, I feel, etc."

Senika said: "O Gautama! You say that there is no self, and nothing that belongs to self. Then, why do you speak of the Eternal, Bliss, the Self, and the Pure?"

“The Buddha said: "Nobly-born One, I have never taught that the six inner and outer ayatanas (sense-spheres) and the six consciousnesses are Eternal, Blissful, the Self, or Pure; but I do declare that the cessation of the six inner and outer ayatanas and the six consciousnesses arising from them is termed the Eternal. Becasue that is Eternal, it is the Self. Because there is Eternity and the Self, it is termed Blissful. Because it is Eternal, the Self and Blissful, it is termed Pure. Nobly-born One, ordinary people abhor suffering and by eliminating the cause of suffering, they may freely/ spontaneously distance themselves from it. This is termed the Self. Therefore, I have spoken of the Eternal, the Self, the Blissful, and the Pure. (alternative rendering into English, by Samuel Beal, of this important passage can be found in the latter's “A Catena of Buddhist Scriptures from the Chinese”, “1871, pp.179-180

“Sena asked: "According to Gotama's opinion, then, that there is no 'I', let me ask what can be the meaning of that description he gives of Nirvana, that it is permanent, full of joy, personal, and pure?" Buddha says: "Illustrious youth, I do not say that the six external and internal organs, or the various species of knowledge, are permanent, etc; but what I say is that “that” is permanent, full of joy, personal, and pure, which is left after the six organs and the six objects of sense, and the various kinds of knowledge are all destroyed. Illustrious youth, when the world, weary of sorrow, turns away and separates itself from the cause of all this sorrow, then, by this voluntary rejection of it, there remains that which I call the True Self; and it is of this I plainly declare the formula, that it is permanent, full of joy, personal, and pure.").

“Senika said: "O World-Honoured One! Great Compassionate One! Explain to me, I pray, how I am to attain the Eternal, Bliss, the Self, and the Pure, about which you speak."

“The Buddha said: "Nobly-born One, the entire world possesses great pride (mana) from the very beginning, which augments pride and also functions as the cause of (further) pride and proud actions. Therefore, beings now experience the results of pride and are not able to eliminate all the klesas (mental/moral defilements) and attain the Eternal, Blissful, the Self, and the Pure. If beings wish to do away with all defilements, what they need to do is , first of all, to make away with pride." (Note: the Sanskrit word for pride, mana, has a different semantic range from the English "pride/ arrogance". It is derived from the verbal root, man (to think, believe, measure, conceive, deem, value, reagrd as) and also means "measure", "computation", "means of proof". The "pride" sense here implies the process of generating or projecting what are implicitly false mental constructs. It refers to the process described in the earlier chapter in the sutra on the four perverse views. - Stephen Hodge).

Senika said: "O World-Honoured One! It is thus, it is thus! All is as your holy teaching says. I had, from the very start, arrogance; I was grounded on the causal relations of this arrogance. That is why I addressed you by the family name of Gautama. I am now removed from such great arrogance. That is why, with the sincerest heart, I seek Dharma. How am I to arrive at the Eternal, Bliss, the Self, and the Pure?"

The Buddha said: "Listen carefully to me, listen carefully! I shall now explain matters to you in detail.

"O good man! If all thoughts of your own self, of others and of beings are done away with, you will segregate yourself from such."

Senika said: "O World-Honoured” “One! I have now understood and gained the right Dharma-Eye."

The Buddha said: "In what way have you known, understood, and gained the right Dharma-Eye?"

"O World-Honoured One! The physical form (“rupa”) of which we speak is not our own, not another's, nor that of beings.” “So does it obtain with all (the skandhas) down to consciousness. Seeing things thus, I have arrived at the right Dharma-Eye. O World-Honoured One! I am now very eager to renounce the world and be admitted into the Order. Be good enough to admit me into the Order!"

The Buddha said: "Welcome, O bhiksu!" At once he was perfect in pure actions, and he attained arhatship.

Among the tirthikas, there was a Brahmacarin (present) by the name of Kasyapa. He also said: "O Gautama! Is the body life? Or are body and life different things?"

The Tathagata said nothing. So he asked a second and a third time. The Brahmacarin again said: "O Gautama! A man dies and does not yet gain his next body. In this in-between state, do we not say that the body is different and the life is different? If they are different, why do you sit silently and not reply?"

"O good man! Body and life both arise from causal relations. I say that nothing comes about without causal relations. As with the body and life, so does it proceed with all things."

The Brahmacarin further said: "O Gautama! I see things in the world that do not proceed in accordance with causal relations."

The Buddha said: "O Brahmacarin! In what way do you see things that do not proceed in accordance with causal relations?"

The Brahmacarin said: "I see trees being burnt. The wind blows out the flakes (cinders, sparks) of fire, which fall in different places. Is this not what has nothing to do with causal relations?"

The Buddha said: "O good man! I say that this fire, too, comes about from causal relations. It is not the case that it does not accord with any cause."

The Brahmacarin said: "O Gautama! When the fire flakes go (i.e. move off), these do not depend upon fuel or charcoal. So how can we say that these are dependent on causal relations?"

The Buddha said: "O good man! Though there is no fuel or charcoal, the wind drives the fire flakes away. Through the causal factor of the wind, the fire does not die out."

"O Gautama! A man dies, but does not yet gain his next body. How can we call the life that exists in between one of causal relations?"

The Buddha said: "O Brahmacarin! Ignorance and craving are the causal relations. Through the causal relations of ignorance and craving, life is able to be sustained. O good man! Through causal relations, the body can be life, and life the body. Through causal relations, the body is different, and life different. A wise person should not say that the body and life are different all through."

The Brahmacarin said: "O World-Honoured One! Please condescend to analyse and explain to me clearly, so that I will truly be able to understand causal relations."

The Buddha said: "O Brahmacarin! The cause is the five skandhas and the result too is the five skandhas. The fire not started, there cannot be any smoke."

The Brahmacarin said: "O World-Honoured One! I now know and I now have understood."

"O good man! In what way have you come to know and in what way have you understood?"

"O World-Honoured One! Fire is the defilement, which truly burns in the realms of hell, hungry pretas, animals, humans and the gods. The smoke is the karmic results which a person harvests, which are non-eternal, non-pure and which emit a bad smell and are defiled and to be despised. Hence, "smoke". If beings do not perform any defilement, there cannot be any karmic result of defilement. That is why the Tathagata says that where there is no fire, there is no smoke. O World-Honoured One! I now see correctly. What I wish for is that you will now allow me to renounce the world?"

Then the World-Honoured One said to Kaundinya: "Admit this Brahmacarin and allow him to receive the precepts."

By order of the Buddha, he reported the matter to all the members of the Sangha and had him take the upasampada. After five days, the man attained arhatship.

Among the tirthikas, there was (present) a Brahmacarin by the name of Purana. He said: "O Gautama! Have you seen the fact that the world is eternal and do you say that it is eternal? Is what is said true or not true? Is it eternal, non-eternal, or eternal and non-eternal, or non-eternal and not non-eternal? Is it something that has a boundary line, is it without a boundary line, is it (both) with and without a boundary line, or is it something which does not have a boundary line or something that has no boundary line? Are the body and life one, or are body and life different? Or after the death of the Tathagata, are you one who has gone, or are you one who is gone and not gone, or one who is not one gone and not one who is not gone?"

The Buddha said: "O Purana! I never say that the world where we live is eternal, falsely made, or real; that it is non-eternal, eternal and non-eternal, or non-eternal and not non-eternal; that it has or has not a boundary line, that it is not one that has a boundary line and one that is not one that has not a boundary line; that this is the body, this is life, that the body and life are different, that after the Tathagata's death, he is one gone, one not gone, one gone and not gone, or that he is not one gone, nor one not gone."

Purana questioned further: "O Gautama! What wrong do you see in this, that you do not say?"

The Buddha said: "O Purana! If any person should say that the world is eternal, and this is real, and that all others are false, this is what is wrongly seen (“drsti”: i.e. a faulty view or vision of things). What this wrong seeing sees is the action of wrong seeing, and this is the karma of wrong seeing, and this is the clinging of wrong seeing, and this is the bondage of wrong seeing, and this is the suffering of wrong seeing, and this is the cleaving of wrong seeing, and this is the fear of wrong seeing, and this is the heat of wrong seeing, and this is the bondage of wrong seeing. O Purana! Common mortals cling to what is wrongly seen, and cannot do away with birth, old age, illness, and death. Repeating lives in the six realms, they suffer from innumerable sorrows. And the same applies to what obtains regarding matters extending to not-gone or not not-gone, also. O Purana! I see in this wrong seeing such a lapse. So I do not cling, and so I do not speak about it to other persons."

"O Gautama! If you see such a lapse, do not cling to it and do not speak about it, O Gautama, what do you now see, cling to, and speak about?"

The Buddha said: "O good man! Now, the clinging of wrong seeing is the dharma of life and death. As the Tathagata has done away with life and death, he does not cling. O good man! The Tathagata is one who well sees and who well speaks. But he is not one who clings."

"O Gautama! In what way do you well see and well speak?"

"O good man! “I well see suffering, the cause of suffering, the extinction (of suffering), and the Way to the extinction of suffering, and discriminate and speak about four such Truths. I see thus. So, I segregate myself from all wrong seeings, all cravings, all streams and arrogances. That is why I am garbed in pure actions, unsurpassed quietude, and the Eternal Body. And this Body also has no east, no west, no south, and no north."

“Purana said: "O Gautama! Why does the Eternal body have no east, no west, no south, and no north?"

The Buddha said: "O good man! I shall now put a question to you. Answer as you will. Why? It is like making a big fire before you. When it burns, do you know whether or not it is burning?"

"That is right. O Gautama!" "When the fire dies, do you know it or not?" "It is thus, it is thus, O Gautama!"

"O Purana! When people ask: "From where does the burning come and where does it go to?", how would you reply?"

"O Gautama! If there were anyone who were to ask this, I should reply: "This fire starts up from various causal relations. When the original causal relation ends and the new causal relation has not yet come about, the fire dies."

"If again there is a person who asks: "When extinguished, where does it go to?", how would you answer?"

"O Gautama! I should answer: "When the causal relations end, it dies. It does not have any direction to turn to."

"O good man! It is the same with the Tathagata, too. If there is any non-eternal form down to non-eternal consciousness, there is burning, because it is based on craving. "Burning" means receiving the 25 existences. Thus one can well say, when it burns, this fire has an easterly, westerly, southerly, or northerly direction. If craving now dies out, the fire of the karmic results of the 25 existences also ceases to burn. When it does not burn, we cannot say that there are the directions of east, west, south, or north. O good man! The Tathagata has already extinguished the cause of non-eternal form and non-eternal consciousness. Hence, his Body is Eternal. His Body being Eternal, we cannot speak of east, west, south, or north."

Purana said: "I wish to make an analogy. Please condescend to give ear to it."

The Buddha said: "Well said, well said! Speak as you will!"

"O World-Honoured One! For example, outside a big village, there is a sal forest. There is a tree in it. Before the forest came into being, it was born, and 100 years passed. The owner of the forest gave water to it and spent timely care upon it. The tree is old and rotten, and the bark, branches and leaves all drop off. What there is is quietude and truth. It is the same with the Tathagata. All that is old is gone; what there is is what is true. O World-Honoured One! I now very much desire to renounce the world and practise the Way."

The Buddha said: "Welcome, O bhiksu!" When the Buddha had said this, Purana at once entered the Path and, defilement gone, attained arhatship.

Also, there was a Brahmacarin by the name of "Pure", who said: "O Gautama! What do all beings not know as a result of which they do not see the eternal and non-eternal of the world, and also the eternal-non-eternal, not eternal and not non-eternal, down to not-gone and not not-gone?"

The Buddha said: "O good man! Not knowing material form down to not knowing consciousness (i.e. the five skandhas), a person does not see the eternal, down to the not-gone and not not-gone of the world."

The Brahmacarin said: "O Gautama! What do beings know, so that they do not see the eternal of the world, down to the not-gone and not not-gone?"

The Buddha said: "O good man! They know material form down to consciousness, so that they do not see the eternal, down to the not-gone and the not not-gone."

The Brahmacarin said: "O World-Honoured One! Please condescend to expound to me the eternal and the non-eternal of the world."

The Buddha said: "O good man! If one casts away the old, and does not create new karma, one truly knows the eternal and the non-eternal."

The Brahmacarin said: "O World-Honoured One! I now know."

The Buddha said: "O good man! In what way do you see and know?"

"O World-Honoured One! What is old is ignorance and craving, and the new is cleaving and (phenomenal, samsaric) existence. If one segregates one's self from the eternal and the non-eternal and has no more cleaving and existence, one will know the true nature of the eternal and the non-eternal. I have now acquired the pure eye of Wonderful Dharma, and I take refuge in the Three Treasures. O Tathagata! Admit me into the Order!"

The Buddha said to Kaundinya: "Admit this Brahmacarin into the Order and let him receive sila."

At these words of the Buddha's, Kaundinya took the man and went to the gathering of monks, and through the ritualistic procedure of karman, the man was admitted into the Order. After 15 days, all his defilements having been eternally extirpated, the man attained arhatship.

Also, the Brahmacarin, Vatsiputriya, said: "O Gautama! I now wish to put some questions to you. Will you indeed allow me to do so?"

The Tathagata sat silently. At the second and third time, he said nothing.

Vatisiputriya said again: "O Gautama! I have long been on friendly terms with you. We could not be two (i.e. divergent) in our acceptations (understanding) in any way. I desire to ask. Why are you silent?"

The World-Honoured One thought: "It is thus, O Brahmacarin! Your nature is gentle and graceful, pure, good, and innocent. You always seek to know. This is not to cause worry to others. I shall answer, to accord with your wish."

The Buddha said: "Well said, well said, O Vatsiputriya! I shall answer what you desire to know."

Vatsiputriya said: "O Gautama! Is there in the world what may be termed "good"?

"It is thus, O Vatsiputriya!"

"Is there "non-good?"

"Yes, that is so."

"O Gautama! Please expound the good and the non-good to me."

The Buddha said: "O good man! I shall speak extensively about it. I shall now analyse and explain (matters) to you in a concise way. Desire is non-good; getting emancipated is that which is good. So are anger and ignorance (non-good). Killing is what is not good; non-killing is what is good. So does it proceed down to the twisted views of life. O good man! I now, for your sake, expound to you the three kinds of what is good and non-good; also the ten kinds of what is good and non-good. If any of my disciples can see the difference between the three kinds of good and non-good, down to the ten kinds of good and non-good, such will indeed do away with all such defilements as desire, anger, and ignorance, and will cut off what is "is" (i.e. samsarically driven, imperfect, ever-changing, phenomenal existence)."

The Brahmacarin said: "O Gautama! Is there any single bhiksu among those of the Buddhist Sangha who does away with all such defilements as desire, anger, and ignorance?"

The Buddha said: "O good man! There are not only one, two, three or five hundred, but innumerable bhiksus who do away with all such defilements and things of the "is", such as desire, anger, ignorance and all such defilements."

"O Gautama! If we exclude the bhiksus, is there any bhiksuni among those of the Buddhist Sangha who has done away with all such defilements and things of the "is", such as desire, anger, and ignorance?"

The Buddha said: "There are not only one, two, three, or five hundred such bhiksunis, but innumerable bhiksunis who have done away with all these defilements and things of the "is", such as greed, anger, and ignorance."

Vatsiputriya said: "O Gautama! Let us leave aside the cases of individual bhiksus or bhiksunis. Is there among those of the Buddhist Sangha any upasaka who has been true to sila and made effort, and has been pure in his deeds, has crossed over the waters of doubt, and having cut away the web of doubt, has attained the other shore?"

The Buddha said: "O good man! There is not just one, two, three or five hundred, but countless upasakas who have been true to sila, who have made effort, whose deeds have been pure, and who, having rent asunder the web of doubt, have destroyed the five bonds of defilement (i.e. greed (or desire), ill-will, ignorance, jealousy, and stinginess, which cause one to get reborn into the three unfortunate realms of hell, ghosts, and animals), attaining thereby the fruition of the anagamin, and who have gained the other shore beyond doubt, doing away with the web of doubt."

Vatsiputriya said: "Let us leave aside the cases of bhiksus, bhiksunis, and upasakas. Is there any upasika among those of the Buddhist Sangha who has been true to sila, who has made effort, who has been pure in her deeds, and who has reached the other shore of doubt, having cut away the web of doubt?"

The Buddha said: "Of such there is not only one, two, three or five hundred, but there are countless upasikas who have been true to sila, who have made effort, who have destroyed the five fetters of defilement, who have attained the fruition of the anagamin, and who are now on the yonder shore of doubt, having cut away the web of doubt."

Vatsiputriya said: "O Gautama! Let us now leave aside the case of bhiksus or bhiksunis who have eliminated all defilements, and the case of upasakas and upasikas who have observed sila, made effort, and whose deeds have been pure, and who have cut away the web of doubt. Is there any upasaka among those of the Buddhist Sangha who enjoys the pleasures of the five (sensual) desires and who has no doubt in his mind?"

"O good man! Of such there is not only one, two, three or five hundred. There are countless people who have destroyed the three bonds, attaining thereby the fruition of the srotapanna and growing less in desire, ill-will, and ignorance, and thus gaining the fruition of the sakrdagamin. It is the same with the upasaka and upasika."

"O World-Honoured One! I would like now to draw an analogy."

The Buddha said: "Well said, well said! Speak out what you desire to say."

"O World-Honoured One! The naga kings, Nanda and Upananda, both provide us with great rains. So does it obtain with the Tathagata's rain of Dharma. All-equally do you let the rain fall upon the upasakas and upasikas. O World-Honoured One! If any tirthikas were to come (here) and desire (to train under you), I wonder how many months you would keep them on probation?"

The Buddha said: "O good man! We test for four months. It is not necessarily to be of one kind (i.e. whatever the type of person who applies)."

"O World-Honoured One! If it is not of one kind, please admit me into the Order."

Then, the World-Honoured One said to Kaundinya: "See that this Vatsiputriya is admitted into the Order and that he receives sila."

At these words of the Buddha, Kaundinya stood up amidst the congregation and carried out the ritual of karman. Fifteen days later, the man attained the fruition of srotapanna. Having attained this fruition, he thought to himself: "If I am to practise the Way with Wisdom, I have now already gained it, and I shall indeed be able to see the Buddha."

Then, he went to where the Buddha was, prostrated himself on the ground, and having paid his homage, drew back and seated himself on one side. And he said to the Buddha: "O World-Honoured One! Whatever is to be attained by knowing, I have now attained. Please condescend again to expound (things) to me, so that I might gain the learninglessness knowledge."

The Buddha said: "O good man! Make effort and practise two things, namely: 1) samatha (calmness meditation) and 2) vipasyana (insight meditation). O good man! If any bhiksu wishes to attain the fruition of the srotapanna, such a person should practise these two things. If anyone desires to attain the fruitions of the sakrdagamin, anagamin, and arhatship, such a person too should practise the same.

"O good man! Any bhiksus who desire to attain the four dhyanas, the four boundless minds, the six divine powers, the eight emancipations, the eight superior places, the non-disputing knowledge, the top knowledge, the ultimate knowledge, the four unhindered knowledges, the Adamantine Samadhi, the all-extinguished knowledge, and the birthlessness knowledge must all practise these two ways.

"O good man! If there is anyone who wishes to attain the ten-abode soil, the birthlessness cognition, the all-wonderfulness cognition, holy actions, pure actions, heavenly actions, Bodhisattva practice, the All-Void samadhi, the jnana-mudra-samadhi, the samadhi of All-Void, formlessness and non-action, the bhumi-samadhi, the non-retrogression samadhi, the Suramgama Samadhi, the Adamantine Samadhi, and the Buddhist action of unsurpassed Bodhi, such a one must practise these two ways."

Vatsiputriya, having heard this, paid homage and left. He practised these two ways in the sal forest, and before long he had attained the fruition of arhatship.

At that time, there were innumerable bhiksus who were on the way to where the Buddha was. Vatsiputriya, on seeing them, asked: "O great ones! Where are you intending to go?"

All the bhiksus said: "We intend to go to the Buddha."

"O great ones! If you go to the Buddha, please tell him: "The Brahmacarin, Vatsiputriya, having practised the two ways, has now attained the learninglessness knowledge. Now, feeling grateful to the Buddha, he enters Nirvana."

Then all the bhiksus, on going to the Buddha, said: "O World-Honoured One! The bhiksu, Vatsiputriya, wanted us to report to you that, having now practised the two ways, he has attained the learninglessness knowledge and that, feeling grateful, he will now enter Nirvana."

The Buddha said: "The Brahmacarin, Vatsiputriya, has now attained the fruition of arhatship. Go now and make offerings to his remains."

Then the bhiksus, at these words of the Buddha, went to where the corpse lay and made great offerings.

The Brahmacarin, Kasaya, then said: "O Gautama! You Gautama say that a person does what is good and not good innumerable times, and in the future gains bodies again that are good or not good. This is not so, because, just as you Gautama say, a person gains a body through defilement. If a person gains his body, does the body come first or the defilement come first? If defilement comes about first, who creates it and where does it stay? If the body comes about first, how can we say that the person gains it through defilement? Because of this, if it is said that defilement comes about first, this does not fit well. It is also not good to say that the body comes about first. If it is said that both come about at the same time, this also will not be right. Any such speaking as of "before" and "after", or of "at the same time", is not acceptable. So I say: "Everything has its own nature, not depending on causal relations."

"Also, next, O Gautama! Hardness is the nature of the earth; moisture is the nature of water; heat is that of fire; movement is that of the wind; and not being obstructed is that of space. These five natures are existences which do not depend on causal relations. If there is in the world but one thing that does not depend on causal relations, it must be thus with all other things, too. What is is the existence that is not grounded on causal relations. If it is said that all depend on the single law of causal relations, why is it that the nature of the five elements does not depend on the law of causal relations?