Factors of enlightenment

The Seven Factors of Enlightenment

BECOMING A NOBLE ONE

One does not become enlightened by merely gazing into the sky. One does not become enlightened by reading or studying the scriptures, nor by thinking, nor by wishing for the enlightened state to burst into one’s mind. There are certain necessary conditions or prerequisites which cause enlightenment to arise. In Pāli these are known as the bojjhaṅgas, or factors of enlightenment, and there are seven of them.

The word bojjhaṅga is made up of bodhi, which means enlightenment or an enlightened person, and aṅga, causative factor. Thus a bojjhaṅga is a causative factor of an enlightened being, or a cause for enlightenment.

A second sense of the word bojjhaṅga is based on alternative meanings of its two Pāli roots. The alternative meaning of bodhi is the knowledge that comprehends or sees the Four Noble Truths:

the truth of universal suffering or unsatisfactoriness;

the truth that desire is the cause of this suffering and dissatisfaction;

the truth that there can be an end to this suffering; and the

truth of the path to the end of this suffering, or the Noble Eightfold Path.

The second meaning of aṅga is part or portion. Thus, the second meaning of bojjhaṅga is the specific part of knowledge that sees the Four Noble Truths.

All vipassanā yogis come to understand the Four Noble Truths to some extent, but true comprehension of them requires a particular, transforming moment of consciousness, known as path consciousness. This is one of the culminating insights of vipassanā practice. It includes the experience of nibbāna. Once a yogi has experienced this, he or she deeply knows the Four Noble Truths, and thus is considered to contain the bojjhaṅgas inside him or herself. Such a person is called noble. Thus, the bojjhaṅgas or enlightenment factors also are parts or qualities of a noble person. Sometimes they are known as the sambojjhaṅgas, the prefix sam- meaning full, complete, correct, or true. The prefix is an honorific and intensifier, and adds no crucial difference in meaning.

These seven factors of enlightenment, or seven qualities of a noble person, are:

mindfulness,

investigation,

effort,

rapture,

calm,

concentration and

equanimity.

In Pāli, the list would be sati, dhamma vicaya, vīriya, pīti, passaddhi, samādhi, upekkha. These seven can be found in all phases of vipassanā practice. But if we take as a model the progressive stages of insight, we can say that the seven enlightenment factors begin to be very clear at the stage of insight where a yogi begins to see the arising and passing of phenomena.

How can one develop these factors in himself or herself? By means of satipaṭṭhāna meditation. The Buddha said, “Oh bhikkhus, if the four foundations of mindfulness are practiced persistently and repeatedly, the seven types of bojjhaṅgas will be automatically and fully developed.”

Practicing the four foundations of mindfulness does not mean studying them, thinking of them, listening to discourses about them, nor discussing them. What we must do is be directly and experientially aware of the four foundations of mindfulness, the four bases on which mindfulness can be established. The satipaṭṭhāna Sutta names them: first, the sensations of the body; second, feeling; the painful, pleasant or neutral quality inherent in each experience; third, the mind and thought; and fourth, all other objects of consciousness;

feelings seen, heard, tasted and so forth. The Buddha said, furthermore, that one should practice this awareness not intermittently, but rather persistently and repeatedly. This is exactly what we try to do in vipassanā meditation. The tradition of vipassanā meditation taught and developed by Mahāsi Sayādaw is oriented toward developing fully the seven factors of enlightenment, and eventually experiencing noble path consciousness, in accordance with the Buddha’s instructions.

MINDFULNESS: THE FIRST ENLIGHTENMENT FACTOR

Sati, mindfulness, is the first factor of enlightenment. “Mindfulness” has come to be the accepted translation of sati into English. However, this word has a kind of passive connotation which can be misleading. “Mindfulness” must be dynamic and confrontative. In retreats, I teach that mindfulness should leap forward onto the object, covering it completely, penetrating into it, not missing any part of it. To convey this active sense, I often prefer to use the words “observing power” to translate sati, rather than “mindfulness.” However, for the sake of ease and simplicity, I will consistently use the word “mindfulness” in this volume, but I would like my readers to remember the dynamic qualities it should possess.

Mindfulness can be well understood by examining its three aspects of characteristic, function and manifestation. These three aspects are traditional categories used in the Abhidhamma, the Buddhist description of consciousness, to describe factors of mind. We will use them here to study each of the enlightenment factors in turn.

Nonsuperficiality

The characteristic of mindfulness is nonsuperficiality. This suggests that mindfulness is penetrative and profound. If we throw a cork into a stream, it simply bobs up and down on the surface, floating downstream with the current. If we throw a stone instead, it will immediately sink to the very bed of the stream. So, too, mindfulness ensures that the mind will sink deeply into the object and not slip superficially past it.

Say you are watching your abdomen as the object of your satipaṭṭhāna practice. You try to be very firm, focusing your attention so that the mind will not slip off, but rather will sink deeply into the processes of rising and falling. As the mind penetrates these processes, you can comprehend the true natures of tension, pressure, movement and so on.

Keeping the Object in View

The function of mindfulness is to keep the object always in view, neither forgetting it nor allowing it to disappear. When mindfulness is present, the occurring object will be noted without forgetfulness.

In order for nonsuperficiality and nondisappearance, the characteristic and function of mindfulness, to appear dearly in our practice, we must try to understand and practice the third aspect of mindfulness. This is the manifestation aspect, which develops and brings along the other two. The chief manifestation of mindfulness is confrontation: it sets the mind directly face to face with the object.

Face to Face with the Object

It is as if you are walking along a road and you meet a traveler, face to face, coming from the opposite direction. When you are meditating, the mind should meet the object in just this way. Only through direct confrontation with an object can true mindfulness arise.

They say that the human face is the index of character. If you want to size up a person, you look at his or her face very carefully and then you can make a preliminary judgment. If you do not examine the face carefully and instead become distracted by other parts of his or her body, then your judgment will not be accurate.

In meditation you must apply a similar, if not sharper, degree of care in looking at the object of observation. Only if you look meticulously at the object can you understand its true nature. When you look at a face for the first time, you get a quick, overall view of it. If you look more carefully, you will pick up details — say, of the eyebrows, eyes and lips. First you must look at the face as a whole, and only later will details become clear.

Similarly, when you are watching the rising and falling of your abdomen, you begin by taking an overall view of these processes. First you bring your mind face to face with the rising and falling. After repeated successes you will find yourself able to look closer. Details will appear to you effortlessly, as if by themselves. You will notice different sensations in the rise and fall, such as tension, pressure, heat, coolness, or movement.

As a yogi repeatedly comes face to face with the object, his or her efforts begin to bear fruit. Mindfulness is activated and becomes firmly established on the object of observation. There are no misses. The objects do not fall away from view. They neither slip away nor disappear, nor are they absent-mindedly forgotten. The kilesas cannot infiltrate this strong barrier of mindfulness. If mindfulness can be maintained for a significant period of time, the yogi can discover a great purity of mind because of the absence of kilesas. Protection from attack by the kilesas is a second aspect of the manifestation of mindfulness. When mindfulness is persistently and repeatedly activated, wisdom arises. There will be insight into the true nature of body and mind. Not only does the yogi realize the true experiential sensations of the rise and fall, but she or he also comprehends the individual characteristics of the various physical and mental phenomena happening inside herself or himself.

Seeing the Four Noble Truths

The yogi may see directly that all physical and mental phenomena share the characteristic of suffering. When this happens we say that the First Noble Truth is seen.

When the First Noble Truth has been seen, the remaining three are also seen. Thus it is said in the texts, and we can observe the same in our own experience. Because there is mindfulness at the moment of occurrence of mental and physical phenomena, no craving arises. With this abandoning of craving, the Second Noble Truth is seen. Craving is the root of suffering, and when craving is absent, suffering, too, disappears. Seeing the Third Noble Truth, the cessation of suffering, is fulfilled when ignorance and the other kilesas fall away and cease. All this occurs on a provisional or moment-to-moment basis when mindfulness and wisdom are present. Seeing the Fourth Noble Truth refers to the development of the Eightfold Path factors. This development occurs simultaneously within each moment of mindfulness. We will discuss the factors of the Eightfold Path in more detail in the next chapter, “Chariot to nibbāna.”

Therefore, on one level, we can say that the Four Noble Truths are seen by the yogi at any time when mindfulness and wisdom are present. This brings us back to the two definitions of bojjhaṅga given above. Mindfulness is part of the consciousness that contains insight into the true nature of reality; it is a part of enlightenment knowledge. It is present in the mind of one who knows the Four Noble Truths. Thus, it is called a factor of enlightenment, a bojjhaṅga.

Mindfulness is the Cause of Mindfulness

The first cause of mindfulness is nothing more than mindfulness itself. Naturally, there is a difference between the weak mindfulness that characterizes one’s early meditative efforts and the mindfulness at higher levels of practice, which becomes strong enough to cause enlightenment to occur. In fact, the development of mindfulness is a simple momentum, one moment of mindfulness causing the next.

Four More Ways to Develop Mindfulness

Commentators identify four additional factors which help develop and strengthen mindfulness until it is worthy of the title bojjhaṅga.

1. Mindfulness and Clear Comprehension

The first is satisampajañña, usually translated as “mindfulness and clear comprehension.” In this term, sati is the mindfulness activated during formal sitting practice, watching the primary object as well as others. Sampajañña, clear comprehension, refers to mindfulness on a broader basis: mindfulness of walking, stretching, bending, turning around, looking to one side, and all the other activities that make up ordinary life.

2. Avoiding Unmindful People

Dissociation from persons who are not mindful is the second way of developing mindfulness as an enlightenment factor. If you are doing your best to be mindful, and you run across an unmindful person who corners you into some long-winded argument, you can imagine how quickly your own mindfulness might vanish.

3. Choosing Mindful Friends

The third way to cultivate mindfulness to associate with mindful persons. Such people can serve as strong sources of inspiration. By spending time with them, in an environment where mindfulness is valued, you can grow and deepen your own mindfulness.

4. Inclining the Mind Toward Mindfulness

The fourth method is to incline the mind toward activating mindfulness. This means consciously taking mindfulness as a top priority, alerting the mind to return to it in every situation. This approach is very important; it creates a sense of unforgetfulness, of non-absentmindedness. You try as much as possible to refrain from those activities that do not particularly lead to the deepening of mindfulness. Of these there is a wide selection, as you probably know.

As a yogi only one task is required of you, and that is to be aware of whatever is happening in the present moment. In an intensive retreat, this means you set aside social relationships, writing and reading, even reading scriptures. You take special care when eating not to fall into habitual patterns. You always consider whether the times, places, amounts and kinds of food you eat are essential or not. If they are not, you avoid repeating the unnecessary pattern.

INVESTIGATION: THE SECOND ENLIGHTENMENT FACTOR

We say that the mind is enveloped by darkness, and as soon as insight or wisdom arises, we say that the light has come. This light reveals physical and mental phenomena so that the mind can see them clearly. It is as if you were in a dark room and were given a flashlight. You can begin to see what is present in the room. This image illustrates the second enlightenment factor, called “investigation” in English and dhamma vicaya sambojjhaṅga in Pāli.

The word “investigation” may need to be elucidated. In meditation, investigation is not carried out by means of the thinking process. It is intuitive, a sort of discerning insight that distinguishes the characteristics of phenomena. Vicaya is the word usually translated as “investigation”; it is also a synonym for “wisdom” or “insight.” Thus in vipassanā practice there is no such thing as a proper investigation which uncovers nothing. When vicaya is present, investigation and insight coincide. They are the same thing.

What is it we investigate? What do we see into? We see into dhamma. This is a word with many meanings that can be experienced personally. Generally when we say “dhamma” we mean phenomena, mind and matter. We also mean the laws that govern the behavior of phenomena. When “Dharnma” is capitalized, it refers more specifically to the teaching of the Buddha, who realized the true nature of “dhamma” and helped others to follow in his path. The commentaries explain that in the context of investigation, the word “dhamma” has an additional, specific meaning. It refers to the individual states or qualities uniquely present in each object, as well as the common traits each object may share with other objects. Thus, individual and common traits are what we should be discovering in our practice.

Knowing the True Nature of Dhammas

The characteristic of investigation is the ability to know, through discernment by a nonintellectual investigation, the true nature of dhammas.

Dispelling Darkness

The function of investigation is to dispel darkness. When dhamma vicaya is present, it lights up the field of awareness, illuminating the object of observation so that the mind can see its characteristics and penetrate its true nature. At a higher level, investigation has the function of totally removing the envelope of darkness, allowing the mind to penetrate into nibbāna. So you see, investigation is a very important factor in our practice. When it is weak, or absent, there is trouble.

Dissipating Confusion

As you walk into a pitch-dark room, you may feel a lot of doubt. “Am I going to trip over something? Bang my shins? Bang into the wall?” Your mind is in confusion because you do not know what things are in the room or where they are located. Similarly, when dhamma vicaya is absent, the yogi is in a state of chaos and confusion, filled with a thousand and one doubts. “Is there a person, or is there no person? Is there a self, or no self? Am I an individual or not? Is there a soul, or is there no soul? Is there a spirit or not?”

You, too, may have been plagued by doubts like this. Perhaps you doubted the teaching of impermanence, suffering, and absence of self. “Are you sure that everything is impermanent? Maybe some things aren’t quite so unsatisfactory as others. Maybe there’s a self-essence we haven’t found yet.” You may feel that nibbāna is a fairy tale invented by your teachers, that it does not really exist.

The manifestation of investigation is the dissipation of confusion. When dhamma vicaya sambojjhanga arises, everything is brightly lit, and the mind sees clearly what is present. Seeing clearly the nature of mental and physical phenomena, you no longer worry about banging into the wall. Impermanence, unsatisfactoriness and absence of self will become quite clear to you. Finally, you may penetrate into the true nature of nibbāna, such that you’ll not need to doubt its reality.

Ultimate Realities

Investigation shows us the characteristics of paramattha dhamma, or ultimate realities, which simply means objects that can be experienced directly without the mediation of concepts. There are three types of ultimate realities: physical phenomena, mental phenomena, and nibbāna.

Physical phenomena are composed of the four great elements, earth, fire, water and air. Each element has separate characteristics which are peculiar to and inherent in it.

When we say “characterized” we could also say “experienced as,” for we experience the characteristics of each of these four elements in our own bodies, as sensations.

Earth’s specific or individual characteristic is hardness. Water has the characteristic of fluidity and cohesion. Fire’s characteristic is temperature, hot and cold. Air, or wind, has characteristics of tightness, tautness, tension or piercing, and an additional dynamic aspect, movement.

Mental phenomena also have specific characteristics. For example, the mind, or consciousness, has the characteristic of knowing an object. The mental factor of phassa, or contact, has the characteristic of impingement.

Please bring your attention right now to the rising and falling of your abdomen. As you are mindful of the movement, you may perhaps come to know that it is composed of sensations. Tightness, tautness, pressure, movement — all these are manifestations of the wind element. You may feel heat or cold as well, the element of fire. These sensations are objects of your mind; they are the dhammas which you investigate. If your experience is perceived directly, and you are aware of the sensations in a specific way, then we can say dhamma vicaya is present.

Investigation can also discern other aspects of the Dhamma. As you observe the rising and falling movements, you may spontaneously notice that there are two distinct processes occurring. On the one hand are physical phenomena, the sensations of tension and movement. On the other hand is consciousness, the noting mind which is aware of these objects. This is an insight into the true nature of things. As you continue to meditate, another kind of insight will arise. You will see that all dhammas share characteristics of impermanence, unsatisfactoriness and absence of self. The factor of investigation has led you to see what is universal in nature, in every physical and mental object.

With the maturation of this insight into impermanence, unsatisfactoriness and absence of self, wisdom becomes able to penetrate nibbāna. In this case, the word dhamma takes nibbāna as its referent. Thus, dhamma vicaya can also mean discerning insight into nibbāna.

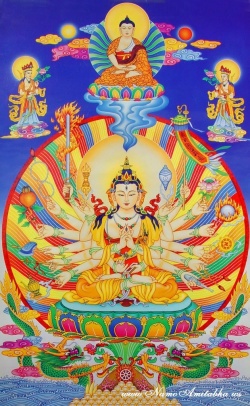

There is something outstanding about nibbāna in that it has no characteristics in common with phenomena that can be perceived. It has specific characteristics of its own, however: permanence, eternity, nonsuffering, bliss and happiness. Like other objects, it is called anatta, nonself, but the nonself nature of nibbāna is different from the nonself of ordinary phenomena in that it does not rest upon suffering and impermanence. It rests instead on bliss and permanence. When the mind penetrates nibbāna, this distinction becomes evident through dhamma vicaya, the investigative discerning insight into the dhamma, which has led us to this place and now allows us to see it clearly.

Spontaneous Insight is the Cause of Investigation

We might be interested in knowing how we can get this factor of investigation to arise. According to the Buddha, there is only one cause of it: there must be a spontaneous insight, a direct perception. To realize such an insight, you must activate mindfulness. You must be aware in a penetrative manner of whatever arises. Then the mind can gain insight into the true nature of phenomena. This accomplishment requires wise attention, appropriate attention. You direct the mind toward the object, mindfully. Then you will have that first insight or direct perception. The factor of investigation arises, and because of it, further insights will follow naturally in order, as a child progresses from kindergarten through high school and college and finally graduates.

Seven More Ways to Develop Investigation

The commentaries speak of seven additional ways to support the arising of investigation as a factor of enlightenment.

The first is to ask questions about the Dhamma and the practice. This means finding a person who is knowledgeable about the Dhamma and speaking with him or her. There is no doubt that Westerners can quite easily fulfill this first requirement. They are adept at asking complicated questions. This capacity is good; it will lead to the development of wisdom.

2. Cleanliness

The second support is cleanliness of what are called the internal and external bases. These are nothing more than the body and the environment. Keeping the internal base, or body, clean means bathing regularly, keeping hair and nails well groomed, and making sure the bowels are free of constipation. Keeping the external base clean means wearing clean and neat clothes and sweeping, dusting and tidying your living quarters. This helps the mind become bright and clear. When the eyes fall upon dirt and untidiness, mental confusion tends to arise. But if an environment is clean, the mind becomes bright and clear. This mental state is ideally conducive to the development of wisdom.

3. A Balanced Mind

The third support for the arising of investigation is balancing the controlling faculties of faith, wisdom, mindfulness, energy and concentration. We treated them at length in an earlier chapter. Four of these five faculties are paired: wisdom and faith, effort and concentration. The practice depends in fundamental ways upon the equilibrium of these pairs.

If faith is stronger than wisdom, one is apt to become gullible or to be carried away by excessive devotional thoughts, a hindrance to practice. Yet, on the other hand, if knowledge or intelligence is in excess, a cunning and manipulative mind results. One can deceive oneself in many ways, even about the truth.

The balance between effort and concentration works like this: if one is overenthusiastic and works too hard, the mind becomes agitated and cannot focus properly on the object of observation. Slipping off, it wanders about, causing much frustration. Too much concentration, however, can lead to laziness and drowsiness. When the mind is still and it seems easy to remain focused on the object, one might begin to relax and settle back. Soon one dozes off.

This balancing of faculties is an aspect of meditation that teachers must understand quite thoroughly in order to guide their students. The most basic way of maintaining balance, and of reestablishing it when it is lost, is to strengthen the remaining controlling faculty, mindfulness.

4-5. Avoiding Fools, Making Friends with the Wise

The fourth and fifth supports for investigation are to avoid foolish, unwise persons and to associate with wise ones. What is a wise person? One person may be learned in the scriptures. Another may be able to think things through with great clarity. If you associate with these people, your theoretical learning will surely increase and you will cultivate a philosophical attitude. This activity is not at all bad. Another sort of wise person, however, can give you knowledge and wisdom beyond what is found in books. The scriptures tell us that the minimum prerequisite defining such a person is that he or she must have practiced meditation and reached the stage of insight into the arising and passing away of all phenomena. If one has not reached this stage, it goes without saying that one should never try to teach meditation, since associating with one’s students will not foster the arising of dhamma vicaya in them.

6. Reflection on Profound Truth

The sixth support for investigation is reflection on profound Dhamma. This instruction to think about something might seem contradictory. Basically it means reflecting on the nature of physical and mental phenomena from the vipassanā point of view: as aggregates, elements and faculties, all of them impersonal.

7. Total Commitment

The last important support for the arising of investigation is total commitment to cultivating this factor of enlightenment. One should always have the inclination toward investigation, toward direct intuitive insight. Remember that it is not necessary to rationalize or intellectualize your experiences. Just practice meditation, so that you can gain a firsthand experience of your own mind and body.

COURAGEOUS EFFORT: THIRD FACTOR OF ENLIGHTENMENT

The third enlightenment factor, effort or vīriya, is the energy expended to direct the mind persistently, continuously, toward the object of observation. In Pāli, vīriya is defined as vīrānaṃ bhāvo, which means “the state of heroic ones.” This gives us an idea of the flavor, the quality, of effort in our practice. It should be courageous effort.

People who are hardworking and industrious have the capacity to be heroic in whatever they do. It is effort itself, in fact, that gives them a heroic quality. A person endowed with courageous effort will be bold in going forward, unafraid of the difficulties he or she may encounter in executing a chosen task. Commentators say that the characteristic of effort is an enduring patience in the face of suffering or difficulty. Effort is the ability to see to the end no matter what, even if one has to grit one’s teeth.

Yogis need patience and acceptance from the very beginning of practice. If you come to a retreat, you leave behind the pleasant habits and hobbies of ordinary life. You sleep little, on makeshift mattresses in tiny cells. Then you get up and spend the day trying to sit immobile and cross-legged, hour upon hour. On top of the sheer austerity of practice, you must be patient with your mind’s dissatisfaction, its longing for the good things of home.

Anytime you actually get down to the work of meditation, moreover, you are likely to experience bodily resistance and some level of pain. Say you are trying to sit still for an hour with your legs crossed. Just fifteen minutes into the sitting, a nasty mosquito comes and bites you. You itch. On top of that, your neck is a bit stiff and there’s a creeping numbness in your foot. You may start to feel irritated. You are used to a luxurious life. Your body is so pampered and spoon-fed that you usually shift its position whenever it feels the slightest discomfort. Now, alas, your body must suffer. And because it is suffering, you suffer as well.

Unpleasant sensations have the uncanny ability to exhaust and wither the mind. The temptation to give up can be very great. Your mind may fill with rationalizations:

“I’ll just move my foot a tiny inch; it’ll improve my concentration.” It may be only a matter of time before you give in.

Patient Endurance

You need courageous effort, with its characteristic of forbearance in the face of difficulty. If you raise your energy level, the mind gains strength to bear with pain in a patient and courageous way. Effort has the power to freshen the mind and keep it robust, even in difficult circumstances. To increase your energy level, you can encourage yourself, or perhaps seek out the inspiration of a spiritual friend or guide. Fed with a bit more energy, the mind grows taut and strong once more.

Support for the Exhausted Mind

Commentators say that effort has the function of supporting. It supports the mind when it withers under attack by pain.

Consider an old, dilapidated house on the point of collapse. A slight gust of wind will bring it tumbling down. If you prop it up with two-by-fours, though, the house can continue to stand. Similarly, a mind withered by pain can be supported by courageous effort and can continue the practice with freshness and vigilance. You may have experienced this benefit personally.

Yogis who suffer from chronic ailments may have difficulty practicing in a regular way. Confronting an ailment again and again saps physical and mental energy; it is taxing and discouraging. It is no surprise that yogis who have sicknesses often come to interviews full of despair and disappointment. They feel they are making no progress. They merely hit a wall again and again. It all seems so futile. Little thoughts occur to them, wanting to give up, wanting to leave the retreat or just stop meditating. Sometimes I can save this situation with a little discourse or a word of encouragement. The yogi’s face lights up and he or she is on the road again for a day or two.

It is very important to have encouragement and inspiration, not only from yourself but from someone else who can help you along, give you a push when you get stuck.

Courageous Mind:

The Story of Citta

The manifestation of effort is a bold, brave and courageous mind. To illustrate this quality, there is a story from the Buddha’s time of a bhikkhunī named Citta. One day she reviewed the suffering inherent in mind and body and was seized by a great spiritual urgency. As a result she renounced the world and took nun’s robes, hoping to free herself from suffering. Unfortunately, she had a chronic ailment which came in spasms, without warning. One day she would feel fine, and then suddenly she would fall ill. She was a determined lady, though. She wanted liberation and was not one to call it quits. Whenever she was healthy she would strive intensely, and when she was sick she continued, though at a lesser pace. Sometimes her practice was very dynamic and inspired. Then the ailment attacked, and she would regress.

Her sister bhikkhunīs worried that Citta would overstrain herself. They warned her to take care of her health, to slow down, but Citta ignored them. She meditated on, day after day, month after month, year after year. As she grew older she had to lean on a staff to move around. Her body was weak and bony, but her mind was robust and strong.

One day Citta decided she was sick of putting up with all this impediment, and made a totally committed decision. She said to herself, “Today I’m going to do my very best without considering my body at all. Either I die today or the kilesas will be vanquished.”

Citta started walking up a hill with her staff. Very mindfully, step by step, she went. Old and thin and feeble, at times she had to get down and crawl. But her mind was persistent and heroic. She was absolutely, totally committed to the Dhamma. Every step she took, every inch she crawled, toward the peak of the hill was made with mindfulness. When she reached the top, she was exhausted, but her mindfulness had not been broken.

Citta made again her resolution to vanquish the kilesas once and for all or to be vanquished by death. She practiced on as hard as she could, and it seems that on that very day she reached her goal. She was filled with joy and rapture, and when she descended the hill it was with strength and clarity of mind. She was a very different person from the Citta who had crawled up the hill. Now she was fresh and robust, with a clear and calm expression. The other bhikkhunīs were astounded to see Citta like this. They asked her by what miracle she had been transformed. When Citta explained what had happened to her, the bhikkhunīs were filled with awe and praise.

The Buddha said, “Far better is it to live a day striving in meditation than one hundred years without striving.” In business, politics, social affairs and education, we always find that the leaders are people who work hard. Hard work brings you to the peak of any field. This is a fact of life. Effort’s role is obvious in meditation as well. Meditation practice takes a great deal of energy. You have to really work to establish continuity of mindfulness and maintain it from moment to moment without a break. In this endeavor there is no room for laziness.

A Heat that Vaporizes Defilements

The Buddha spoke of energy as a kind of heat, ātāpa. When the mind is filled with energy, it becomes hot. This mental temperature has the power to dry up defilements. We can compare the kilesas to moisture; a mind devoid of energy is easily dampened and weighed down by them. If effort is strong, however, the mind can vaporize kilesas before it is even touched by them. Thus, when the mind is energized by effort, mental defilements cannot touch it, or even come near. Unwholesome states cannot attack.

On matter’s molecular level, heat appears as increased vibration. A red-hot iron bar is actually vibrating rapidly, and it becomes flexible and workable. This is so in meditation, too. When effort is strong, the increased vibration in the mind is manifested as agility. The energized mind jumps from one object to another with ease and quickness. Contacting phenomena, it heats them up, melting the illusion of solidity, so that passing away is clearly seen.

Sometimes when momentum is strong in practice, effort carries on by itself, just as an iron bar remains red-hot for a long time after it has left the fire. With the kilesas far away, clarity and brightness appear in the mind. The mind is pure and clear in its perception of what is happening. It becomes sharp, and very interested in catching the details of phenomena as they arise. This energetic mindfulness allows the mind to penetrate deeply into the object of observation and to remain there without scattering and dispersing. With mindfulness and concentration established, there is space for clear intuitive perception, wisdom, to arise.

Through diligent effort, then, the wholesome factors of mindfulness, concentration and wisdom arise and strengthen, and bring with them other wholesome, happy states. The mind is clear and sharp, and it begins to enter more deeply into the true nature of reality.

Disadvantages of Laziness and Delights of Freedom

If instead there is sloppiness and laziness, your attention becomes blunt and noxious states of mind creep in. As you lose focus, you do not care whether you are in a wholesome state of mind or not. You might think your practice can coast along with no help from you. This kind of audacity, a lazy sort of boldness, can undermine you, slow you down. Your mind becomes damp and heavy, full of negative and unwholesome tendencies, like a mildewed horse blanket that has been left out in the rain.

Ordinarily the kilesas pull the mind into their field of sensual pleasures. This is especially true for rāga, lust, one aspect of desire. People who are devoid of courageous effort are helpless in rāga’s grip. They sink again and again into the field of sensual pleasures. If effort is injected into the mind, though, the mind can free itself from this harmful energy field. The mind becomes very light, like a rocket that has succeeded in entering the weightlessness of outer space. Freed from the heaviness of desire and aversion, the mind fills instead with rapture and calm, as well as other delightful, free states of mind. This kind of delight can only be enjoyed through the fire of one’s own efforts.

You may have experienced this freedom personally. Perhaps one day you were meditating while someone was baking cookies nearby. A delicious smell came floating into your nostrils. If you were really mindful, you simply noted this smell as an object. You knew it was pleasant, but no attachment or clinging arose. You weren’t compelled to get up from your cushion and ask for one of those cookies. It might have been similar had an unpleasant object come to you. You would have felt no aversion. Confusion and delusion may also have been absent. When you see clearly the nature of mind and matter, unwholesome factors cannot control you.

Food can be one of the most difficult areas for meditators, especially on retreat. Leaving aside the whole problem of greed, yogis often feel strong disgust toward food. When one is really mindful, one can make the shocking discovery that food is quite tasteless on the tongue. As practice deepens, some yogis begin to find food so repulsive that they are unable to eat more than one or two bites. Alternatively, when yogis experience strong rapture, this rapture becomes a nourishment for their minds, such that they entirely lose their appetite. Both of these types of yogis should try to overcome their initial reactions and make a concerted effort to eat sufficient food to maintain their energy. When the body is deprived of physical nutriment it loses strength and stamina, and eventually this undermines the meditation practice.

One may dream of getting the benefits of vīriya, but if one does not actually strive for them, it is said that one wallows in disgust. The Pāli word for such a person is kusīta. In the world a person who does not work to support him or herself and family will be looked down upon by others. He or she might be called a lazybones or insulted in various ways. The word kusīta refers specifically to someone who is abused verbally. In practice it is the same. At times energy is essential. A yogi who cannot muster the effort to confront a difficult experience, but cringes instead, could be said to be “chickening out.” He or she has no courage, no sense of boldness, no bravery at all.

A lazy person lives in misery, lives with suffering. Not only is he or she held in low esteem by others, but also kilesas arise easily when effort is low. Then the mind is assailed by the three kinds of wrong thoughts: thoughts of craving, of destruction and of cruelty. These mental states are oppressive, painful and unpleasant in themselves. A lazy person can easily be pounced upon by sloth and torpor, another unpleasant state. Furthermore, without energy it may be difficult to maintain the basic precepts. One breaks the precepts at one’s own expense; one loses the joy and benefit of moral purity.

The work of meditation is seriously undermined by laziness. It robs a yogi of the chance to see into the true nature of things, or to raise his or her mind to greater heights. Therefore, the Buddha said, a lazy person loses many beneficial things.

Persistence

For effort to develop to the point of being a factor of enlightenment, it must have the quality of persistence. This means that energy doesn’t drop or stagnate. Rather, it continually increases. With persistent effort, the mind is protected from wrong thoughts. There is so much energy that sloth and torpor cannot arise. Yogis feel a sort of durability of precepts, as well as of concentration and insight. They experience the benefit of effort, a mind that is bright and clear and full of strength, active and energetic.

Understanding about good effort is clear just after one has enjoyed a major success in meditation. Perhaps one has watched extremely painful sensations and penetrated them without reacting or becoming oppressed by them. The mind feels a great satisfaction and heroism in its own accomplishment. The yogi realizes for himself or herself that, thanks to effort, the mind has not succumbed to difficulty but has gone beyond it and has emerged victorious.

Wise Attention is the Cause of Energy

The Buddha was brief in describing how effort or energy arises. It is caused by wise attention, he said, wise reflection on being committed to arousing the three elements of effort.

Stages of Energy: Leaving the Field of the Kilesas

The Buddha’s three elements of effort are launching effort, liberating effort, and persistent effort.

Launching effort is needed at the beginning of a period of practice, particularly on a retreat. At first the mind is overwhelmed by the new situation, and may long for all the things left behind. To get moving on the path of meditation, you reflect on the benefits of your task and then start really putting in the effort to be mindful. When a yogi first starts to practice, only very basic objects are prescribed. You are directed just to watch the primary object and only to attend to other objects when they become distracting. This simple yet fundamental endeavor comprises the first kind of effort, launching effort. It is like the first stage of a rocket which gets the rocket off the ground.

Once you can be mindful of the primary object for some time, you still do not always have smooth sailing. Hindrances come up, or painful sensations, or sleepiness. You find yourself an innocent victim of pain, impatience, greed, drowsiness and doubt. Perhaps you have been enjoying some degree of calm and comfort because you have been able to stay with the primary object, but suddenly difficult objects assault you. At this time the mind has a tendency to become discouraged and lazy. Launching effort is no longer enough. You need an extra boost to face pain and sleepiness, to get above the hindrances.

The second stage of energy, liberating energy, is like the second stage of a rocket which pushes through the earth’s atmosphere. Encouragement from a teacher might help here, or you can reflect for yourself on the good reasons to arouse liberating energy. Armed with internal and external encouragements, you now make a concerted effort to observe the pain. If you are able to overcome your difficulty, you will feel very exhilarated; your energy will surge. You will be ready to go for anything that comes into your field of awareness. Perhaps you overcome a back pain, or you look into an attack of drowsiness and see that it vanishes like a little wisp of cloud. The mind grows refreshed, bright and clear. You may feel an energy high. This is the direct experience of liberating energy.

After this the practice may go smoothly, and the mind may feel satisfied. Do not be surprised if the teacher suddenly assigns you extra homework, such as asking you to pay attention to several touch points on the body. This guidance is to encourage persistent energy, the third kind of energy. Persistent energy is necessary to keep deepening your practice, drawing you toward your goal. It is like the third stage of a rocket which gives it the energy to escape altogether from the earth’s gravitational field. As you develop persistent energy, you will begin to travel through the stages of insight.

It is easy to forget that the temporary happiness you feel today in practice will pass away when you return to the world, unless you attain some deeper level of peace. You might reflect on this for yourself. Why are you practicing? I feel that the minimum goal is to become a sotāpanna, or stream enterer, to reach the first stage of enlightenment, which frees you from rebirth in dangerous and painful lower realms. Whatever your goal is, you should never be complacent until you reach it. For this you need to develop a persistent effort that neither decreases nor stagnates. It grows and grows until it finally brings you to your destination. When effort is well developed in this way, it is called in Pāli paggahita vīriya.

Finally, at the end of practice, effort achieves a fourth aspect, called fulfilling effort. This is what takes you completely beyond the gravity field of sense pleasures into the freedom of nibbāna. Perhaps you are interested to see what this is like? Well, make an effort and you might find out.

Eleven More Ways to Arouse Energy

The commentaries list eleven ways to arouse energy.

1. Reflecting on States of Misery

The first is to reflect on the fearsomeness of the states of apaya, or misery, which you can fall into if you are lazy. The meaning of apa is “devoid of.” Aya, in turn, refers to the wholesome kamma that can bring about happiness — specifically, the kinds of happiness that can be experienced as a human, as a deva, as a brahma, and in nibbāna.

Thus, if you do not practice, you might go into states and realms where you only have the chance to produce unwholesome kamma. There are several realms of unfortunate rebirths. Of these, the easiest for you to observe, and therefore accept, is the animal world. Consider the animals on earth, in the sea, in the air. Can any of them perform wholesome kamma, activities that are free from blame?

Animals live in a haze of delusion. They are covered by a tremendously thick layer of ignorance, of unknowing. Insects, for example, are rather like machines, programmed by their genetic material to carry out certain activities without the slightest capacity for choice, learning, or discernment. Most animals’ mental processes are restricted to concerns about mating and survival. In their world, character roles are incredibly simple.

You are predator or prey or both. It is a vicious realm where only the fittest survive. Imagine the fear and paranoia there must be in the mind of a being living under such pitiless conditions. Imagine the distress and suffering when one creature dies in the jaws of another. Dying with so much suffering, how can animals gain rebirth in a good life? The quality of the mind at death determines the quality of the next rebirth. How can animals ever escape from their fearful existence?

Do animals have the capacity to be generous? Can they be moral? Can they keep precepts? Not to mention this noble and demanding task of meditation. How can animals ever learn to control and develop their minds to maturity? It is frightening and fearful to contemplate a life where the only option is to behave in unwholesome ways.

Reflecting thus may encourage your effort. “I’m a yogi right now. This is my chance. How can I waste time lazing about? Imagine if my next rebirth was as an animal. I wouldn’t ever develop the enlightenment factor of effort. I must not waste time! Now is the time to strive!”

2. Reflecting on the Benefits of Energy

A second way to arouse energy is to reflect on energy’s benefits, some of which have been described above. You have a precious opportunity to come into contact with the Dhamma, the Buddha’s teaching. Having gotten into this incomparable world of Dhamma, you should not waste the opportunity to walk the path that leads to the essence of his teaching! You can attain supramundane states, four successive levels of noble path and fruition, nibbāna itself. Through your own practice, you can conquer suffering.

Even if you do not work to become completely free from all suffering in this lifetime, it would be a great loss not to become at least a sotāpanna, or stream enterer, and thus never again be reborn in a state of misery. Walking this path isn’t just for any Dick or Jane, however. A yogi needs a lot of courage and effort. He or she must be an exceptional person. Strive with diligence and you can attain the great goal! You should not waste a chance to walk a path that leads to the essence of the Buddha’s teaching. If you reflect in this way, perhaps energy and inspiration will arise, and you will put in more effort in your practice.

3. Remembering the Noble Ones

Thirdly, you can remind yourself of the noble persons who have walked this path before you. This path is no dusty byway. Buddhas from time immemorial, the silent Buddhas, the great disciples, the arahants and all the rest of the noble ones, all have walked here. If you want to share this distinguished path, fortify yourself with dignity and be diligent. No room for cowards or the lazy; this is a road for heroes and heroines.

Our ancestors on this path were not just a bunch of misfits who renounced the world to escape from debts and emotional problems. The Buddhas and noble ones were often quite wealthy, and came from loving families. If they had continued their lives as lay persons they would undoubtedly have had a good time. Instead, they saw the emptiness of the worldly life and had the foresight to conceive of a greater happiness and fulfillment, beyond common sensual pleasures.

There also have been many men and women whose humble origin, consciousness of oppression by society or a ruler, or battle against ill health has granted them a radical vision — a wish to uproot suffering, rather than to alleviate it only on the worldly level, or to seek revenge for the wrongs done against them. These people joined their more privileged counterparts on the road to liberation. The Buddha said that real nobility depends on inner purity, not on social class. All of the Buddhas and noble disciples possessed a noble spirit of inquiry and a desire for higher and greater happiness, because of which they left home to walk on this path which leads to nibbāna. It is a noble path, not for the wayward or for dropouts.

You might say to yourself: “People of distinction have walked this path, and I must try to live up to their company. I can’t be sloppy here. I shall walk with as much care as possible, fearlessly. I have this chance to belong to a great family, the group of distinguished people who walk on this noble path. I should congratulate myself for having the opportunity to do this. People like me have walked on this path and attained the various stages of enlightenment. So I, too, will be able to reach the same attainment.”

Through such reflection, effort can arise and lead you to the goal of nibbāna.

4. Appreciation for Support

A fourth causative means for arousing effort is respect and appreciation for alms food and the other requisites essential to a renunciate’s way of life. For ordained monks and nuns, this means respecting the donations of lay supporters, not only at the moment that the gift is made, but also by having a continuous awareness that the generosity of others makes possible the continuation of one’s practice.

Lay yogis also may be dependent on others’ support in many ways. Parents and friends may be helping you, either financially or by taking care of your business so that you can participate in intensive retreats. Even if you pay your own way on a retreat, nonetheless many things are provided to support your practice. The building which shelters you is ready-made; water and electricity are taken care of. Food is prepared by volunteers, and your other needs are cared for. You should have a deep respect and appreciation for the service given to you by people who may not owe you anything, people who have good hearts and deep benevolence.

You can say to yourself, “I should practice as hard as possible to live up to the goodness of those people. This is the way to reciprocate and return the goodwill shown by faithful supporters. May their efforts not go to waste. I will use what I am given with mindfulness so that my kilesas will be slowly trimmed and uprooted, so that my benefactors’ meritorious deeds will bring about an equally meritorious result.”

The Buddha laid down rules of conduct to govern the orders of bhikkhus and bhikkhunīs, monks and nuns. One of these rules was permission to receive what is offered by well-wishing lay supporters. This was not to enable monks and nuns to live a luxurious life. Requisites could be accepted and used in order that monks and nuns might care for their bodies appropriately, giving them the basic right conditions for striving to get rid of the kilesas. Receiving support, they could devote all their time to practicing the threefold training of sīla, samādhi and paññā, eventually gaining liberation from all suffering.

You might reflect that it is only by practicing diligently that you can reciprocate or return the goodwill shown by your supporters. Seen in this way, energetic mindfulness becomes an expression of gratitude for all the help you have received in your meditation practice.

5. Receiving a Noble Heritage

The fifth means to arouse energy is reflection on having received a noble heritage. The heritage of a noble person consists of seven nonmaterial qualities: faith or saddhā; morality or sīla; moral shame and moral dread or hirī and ottappa, discussed at length in “Chariot to nibbāna,” the last chapter of this book; knowledge of the Dhamma, and generosity — one is very generous in giving up the kilesas, and in giving gifts to others; and lastly, wisdom, which refers to the series of vipassanā insights and finally the wisdom of penetrating into nibbāna.

What is extraordinary about this inheritance is that these seven qualities are nonmaterial and therefore not impermanent. This contrasts with the heritage you may receive from your parents upon their death, which is material and therefore subject to loss, decay and dissolution. Further more, material inheritances may be unsatisfying in various ways. Some people quickly squander whatever they receive. Others do not find their new possessions useful. The heritage of a noble one is always beneficial; it protects and ennobles. It follows its heir through the gates of death, and throughout the remainder of his or her saṃsāric wanderings.

In this world, however, if children are unruly and wayward, their parents may disown them so that the children receive no material inheritance. Similarly in the world of the Dhamma, if one has come into contact with the Buddha’s teaching, and then is sloppy and lazy in practice, one will again be denied the seven types of noble heritage. Only a person endowed with enduring and persistent energy will be worthy of this noble inheritance.

Energy is fully developed only when one is able to go through all the levels of insight, up to the culmination of the series in noble path consciousness. This developed energy, or Fulfilling Energy as it is called, is precisely what makes one worthy of the full benefits of the noble heritage.

If you continue to perfect the effort of your practice, these qualities will become permanently yours. Reflecting in this way, you may be inspired to practice more ardently.

6. Remembering the Greatness of the Buddha

A sixth reflection which develops energy is considering the greatness and ability of the person who discovered and taught this path to liberation. The Buddha’s greatness is demonstrated by the fact that Mother Earth herself trembled on seven occasions during his life. The earth first trembled when the Bodhisatta (Sanskrit: Bodhisattva), the future Buddha, was conceived for the last time in his mother’s womb. It trembled again when Prince Siddhattha left his palace to take up the homeless life of a renunciate, and then when he attained supreme enlightenment.

The earth trembled a fourth time when the Buddha gave his first sermon, a fifth time when he succeeded in overcoming his opponents, a sixth time when he returned from Tāvatiṃsa Heaven, having given a discourse on Abhidhamma to his mother who had been reborn there. The earth trembled for the seventh time when the Buddha attained Parinibbāna, when he passed from conditioned existence forever at the moment of his physical death.

Think of the depth of compassion, the depth of wisdom the Buddha possessed! There are innumerable stories of his perfections: how long and devotedly the Bodhisatta worked toward his goal, how perfectly he attained it, how lovingly he served humanity afterwards. Remember that if you continue to strive, you too can share the magnificent qualities the Buddha had.

Before the Buddha’s great enlightenment, beings were engulfed in clouds of delusion and ignorance. The path to liberation had not yet been discovered. Beings groped in the dark. If they sought liberation, they had to invent a practice or follow someone who made a claim to truth that was, in fact, unfounded. In this world a vast array of pursuits have been devised for the goal of attaining happiness. These range from severe sell-mortification to limit less indulgence in sense pleasure.

A Vow to Liberate All Beings

One of the Buddha’s previous existences was as a hermit named Sumedha. This was during a previous eon and world system, when the Buddha immediately previous to this one, Dīpaṅkara, was alive. The hermit Sumedha had a vision of how much beings suffered in darkness prior to the appearance of a sammā sambuddha, a fully enlightened Buddha. He saw that beings needed to be led safely across to the other shore; they could not arrive alone. Due to this vision, the hermit renounced his own enlightenment, for which he had a strong potential in that particular existence. He vowed instead to spend incalculable eons, however long it would take, to perfect his own qualities to the level of a sammā sambuddha. This would give him the power to lead many beings to liberation, not just himself.

When this being finally completed his preparations and arrived at his lifetime as the present Buddha, he was truly an extraordinary and outstanding person. Upon his great enlightenment, he was endowed with what are known as “the three accomplishments”: the accomplishment of cause, the accomplishment of result, and the accomplishment of service.

He was accomplished by virtue of the cause which led to his enlightenment, that is, the effort he put forth during many existences to perfect his paramis, the forces of purity in his mind. There are many stories of the bodhisatta’s tremendous acts of generosity, compassion and virtue. In lifetime after lifetime, he sacrificed himself for the benefit of others. Thus developed, his purity of mind was the foundation for his attainment under the Bo Tree of enlightenment and omniscient knowledge.

That attainment is called the accomplishment of result because it was the natural result of his accomplishment of cause, or the development of very strong powers of purity in his mind. The Buddha’s third accomplishment was that of service, helping others through many years of teaching. He was not complacent about his enlightenment, but out of great compassion and loving care for all those beings who were trainable, he set forth after his enlightenment and tirelessly shared the Dhamma with all those beings who were ready for it, until the day of his Parinibbāna.

Reflecting on various aspects of the Buddha’s three great accomplishments may inspire you to greater effort in your own practice.

Compassion Leads to Action

Compassion was the Bodhisatta Sumedha’s sole motivation for sacrificing his own enlightenment in favor of making the incredible effort to become a Buddha. His heart was moved when he saw, with the eye of great compassion, how beings suffered as a result of misguided activities. Thus he vowed to attain the wisdom necessary to guide them as perfectly as possible.

Compassion must lead to action. Furthermore, wisdom is required so that action may bear useful fruit. Wisdom distinguishes the right path from the wrong path. If you have compassion but no wisdom, you may do more harm than good when you try to help. On the other hand, you may have great wisdom, may have become enlightened, but without compassion you will not lift a finger to help others.

Both wisdom and compassion were perfectly fulfilled in the Buddha. Because of his great compassion for suffering beings, the Bodhisatta was able to go through his samsaric wanderings with enduring patience. Others insulted and injured him, yet he was able to bear these actions with perseverance and endurance. It is said that if you were to combine the compassion that all the mothers on this planet feel for their children, it would still not come near the Buddha’s great compassion. Mothers have a great capacity for forgiveness. It is no easy task to bring up children. Children can be very cruel, and at times they can inflict emotional and physical harm on their mothers. Even when harm is grievous, however, a mother’s heart usually has space to forgive her child. In the Buddha’s heart this forgiving space was boundless. His capacity for forgiveness was one of the manifestations of his great compassion.

Once upon a time the Bodhisatta was born as a monkey. One day he was swinging around in the forest and happened upon a Brahman who had fallen in a crevice. Upon seeing the poor Brahman helpless, the monkey was filled with compassion. This feeling had a great deal of momentum behind it, for by then the Bodhisatta had spent many lifetimes cultivating his parami, or perfection, of compassion.

The Bodhisatta prepared to leap into the crevice to save the Brahman but he wondered if he had the strength to carry the Brahman out. Wisdom arose in his mind. He decided he should test his capability on a boulder he saw lying nearby. Lifting the boulder and setting it down again, he learned that he would be able to accomplish the rescue.

Down the Bodhisatta went and bravely carried the Brahman to safety. Having carried first the boulder and then the Brahman himself, the monkey fell to the ground in exhaustion. Far from being grateful, the Brahman picked up a rock and smashed the monkey’s head, so that he could take home the meat for his supper. Awakening to find himself near death, the monkey realized what had happened but did not get angry. This response was due to his perfected quality of forgiveness. He did say to the Brahman, “Is it proper for you to kill me when I’ve saved your life?”

Then the Bodhisatta remembered that the Brahman had lost his way in the forest and would not be able to get home without help. The monkey’s compassion knew no bounds. Clenching his teeth, he refused to die until he had led the Brahman out of the forest. A trail of blood fell from his wound as the monkey instructed the Brahman which way to turn. Upon reaching the right trail, the monkey expired.

If the Buddha had this much compassion and wisdom even as a monkey, you can imagine how much more he had developed these perfections by the time of his enlightenment.

Full Illumination

After innumerable existences as a Bodhisatta, the Buddha-to-be was born as a human being in his last existence. Having perfected all the paramis, he began searching for the true path to liberation. He endured many trials before he finally discovered the noble path by which he came to see deeply impermanence, unsatisfactoriness and absence of self in all conditioned phenomena. Deepening his practice, he went through the various stages of enlightenment and eventually became an arahant, completely purified of greed, hatred and delusion. Then, the omniscient knowledge he had cultivated arose in him, together with the other knowledges particular to Buddhas. His omniscience meant that if there was anything the Buddha wished to know about, he had only to reflect upon the question, and the answer would come to his mind spontaneously.

As a result of his illumination, the Buddha was now endowed with “The Accomplishment by Virtue of Fruition of Result,” as its full title is known. This accomplishment came about because of the fulfillment of certain causes and prerequisites he had cultivated in his previous lives.

Having become a perfectly enlightened Buddha, he did not forget the intention he had resolved upon so many eons ago when he’d been the hermit Sumedha. The very purpose of his working so hard and long was to help other beings cross the ocean of suffering. Now that the Buddha was completely enlightened, you can imagine how much more powerful and effective his great compassion and wisdom had become.

Based on these two qualities, he began to preach the Dhamma and continued to do so for forty-five years, until his death. He slept only two hours a night, dedicating the rest of his time to the service of the Dhamma, helping other beings in various ways so that they could benefit and enjoy well-being and happiness. Even on his deathbed he showed the path to Subhadda, a renunciate of another sect, who thereby became the last of many disciples to be enlightened by the Buddha.

The full title of this third accomplishment is “The Accomplishment of Seeing to the Welfare of Other Beings,” and it is a natural consequence of the previous two. If the Buddha could become enlightened and totally freed from the kilesas, why did he continue to live in this world? Why did he mingle with people at all? One must understand that he wanted to relieve beings of their suffering and put them on the right path. This was the purest compassion and the deepest wisdom on his part.

The Buddha’s perfect wisdom enabled him to distinguish what was beneficial and what was harmful. If one cannot make this crucial distinction, how can one be of any help to other beings? One may be wise indeed, knowing full well what leads to happiness and what to misery, but then, without compassion one might feel quite indifferent to the fates of other beings. Thus it was the Buddha’s practical compassion which led him to exhort people to avoid unskillful actions that bring harm and suffering. And it was wisdom that allowed him to be selective, precise and effective in what he admonished people to do. The combination of these two virtues, compassion and wisdom, made the Buddha an unexcelled teacher.

The Buddha had no selfish thoughts of gaining honor, fame or the adulation of many followers. He did not mingle with people as a socialite. He approached beings with the sole intention of pointing out the correct way to them so that they could be enlightened to the extent of their capacities. This was his great compassion. When he had finished this duty, the Buddha would retire to a secluded part of the forest. He did not stay among the crowds, bantering and mixing freely like a common person. He did not introduce his pupils to each other, saying, “Here’s my disciple the wealthy merchant; here’s the great professor.” It is not easy to live a solitary and secluded life. No ordinary worldling can enjoy total seclusion. But then, the Buddha was not ordinary.

Advice for Spiritual Teachers

This is an important point for anyone aspiring to become a preacher of the Dhamma or a meditation teacher. One should exercise great discretion in relating with students.

If one has any relationship at all with them, one must remember always to be motivated by great compassion, following the footsteps of the Buddha. There is danger in becoming too close and familiar with those who are being helped. If a meditation teacher becomes too close to his or her students, disrespect and irreverence may be the result.

Meditation teachers should also take the Buddha as their model for the proper motivation in sharing the Dhamma with others. One should not be satisfied with becoming a popular or successful Dhamma teacher. One’s motivation must be, instead, genuinely benevolent. One must strive to benefit one’s students through presenting a technique whose actual practice can tame the behavior of body, speech and mind, thereby bringing true peace and happiness. Teachers must continually examine their own motivations in this regard.

Once I was asked what was the most effective way to teach meditation. I replied, “First and foremost, one should practice until one is dexterous in one’s own practice. Then one must gain a sound theoretical knowledge of the scriptures. Finally, one must apply these two, based on a motivation of genuine lovingkindness and compassion. Teaching based on these three factors will doubtless be effective.”

In this world many people enjoy fame, honor and success due to uncanny strokes of fate or kamma. They may not really have fulfilled the accomplishment of cause, as the Buddha did. That is, they may not have worked hard, but simply became successful or wealthy by a fluke. Such people are likely to receive a lot of criticism. People might say, “It’s a wonder how he or she got into that position, considering how sloppy and lazy he or she is. He or she doesn’t deserve such luck.”

Other people may work very hard. But perhaps because they are neither intelligent nor gifted, they attain their goal slowly, if at all. They are unable to fulfill the accomplishment of result. People like this are not free from blame either. “Poor old so-and-so. He or she works hard, but does not have much for brains.”

Yet another group of people work very hard and become successful. Having fulfilled their ambition, they then rest upon their laurels, so to speak. Unlike the Buddha, who turned his own glorious achievements to the service of humanity, they do not take any further steps by helping society or other beings. Again, these people will be criticized. “Look how selfish he or she is. He or she’s got so much property, wealth, and talent, but no compassion or generosity.”

In this world it is difficult to be free from blame or criticism. People will always talk behind one another’s backs. Some criticisms are merely gossip, and others are deserved, pointing to some real flaw or lack in a person. The Buddha was indeed an exceptional human being in having fulfilled the accomplishments of cause, of result, and of service.

One could write an entire book describing the greatness and perfection of the Buddha, the discoverer and teacher of the path to freedom. Here, I only wish to open the doors for you to contemplate his virtues so that you can develop effort in your practice.

Contemplating the Buddha’s greatness, you may be filled with awe and adoration. You may feel deep appreciation for the wonderful opportunity to walk the path which such a great individual discovered and taught. Perhaps you will understand that in order to walk on such a path, you cannot be sloppy, nor sluggish, nor lazy.

May you be inspired. May you be brave, strong and enduring, and may you walk this path to its end.

9. Avoiding Lazy People

The ninth way to arouse effort is to avoid the company of lazy persons. There are people who are not interested in mental development, who never try to purify themselves. They just eat, sleep and make merry as much as they want. They are like pythons, who swallow their prey and remain immobile for hours. How will you ever be inspired to put forth energy in the company of such people? You should try to avoid becoming a member of their gang. Avoiding their company is a positive step in developing energy.

10. Seeking Energetic Friends

Now you should take another step and choose to associate instead with yogis who are endowed with developed, enduring and persevering energy. This is the tenth way of arousing effort. Most specifically it refers to a yogi in retreat, but in fact, you will be well off spending time with anyone who is totally committed to the Dhamma, enduring and resolute, trying to activate mindfulness from moment to moment, and maintaining a high standard of progressive or persistent energy. People who give top priority to mental health are your best companions. In a retreat you can learn from the people who seem to be model yogis. You can emulate their behavior and practice, and this will lead to your own development. You should allow others’ diligence to be contagious. Take in the good energy, and allow yourself to be influenced by it.

11. Inclining the Mind toward Developing Energy

The last and best way to arouse energy is persistently to incline the mind toward developing energy. The key to this practice is to adopt a resolute stand. “I will be as mindful as I can at each moment, sitting, standing, walking, going from place to place. I will not allow the mind to space out. I will not allow a moment of mindfulness to be missing.” If, on the contrary, you have a careless, self-defeating attitude, your practice will be doomed from the start.

Every moment can be charged with this courageous effort, a very consistent and enduring energy. If a moment of laziness dares to tiptoe in, you will catch it right away and shoo it out! Kosajja, laziness, is one of the most undermining and subversive elements in meditation practice. You can eradicate it by effort: courageous, persistent, persevering, enduring effort.

I hope you will arouse energy through any and all of these eleven ways, so that you will make swift progress in the path and eventually attain that consciousness which uproots defilements forever.

see also: bodhi-pākṣika-dharma