Buddhist Ethics and Environmental Concerns

Buddhist Ethics and Environmental Concerns

Submitted by:

Dr. Arvind Kumar Singh

Assistant Professor, School of Buddhist Studies & Civilization

Gautam Buddha University, Greater Noida

Gautam Buddha Nagar, Utar Pradesh-201312 (INDIA)

Email: arvindbantu@yahoo.co.in

Religious ethics is viewed as being created largely within a context quite different from our present world. The complexity of contemporary moral problems, as found in prostitution, abortion, mercy killing, genetics research, and science-based human reproduction, human cloning, and so on, results mainly from the complicated relationships between people and society and among individuals. The religious precepts are best served in ancient communities increasingly appear ineffectual. Buddhist ethics must evolve to become relevant to the moral dilemmas of the modern world. Discerning that way to reinvent Buddhist ethics is a difficult. It can never be claimed that there is only one way of interpreting Buddhist ethics suitable for responding to the present world’s moral problems.

First of all, Buddhist ethics should be understood to belong to the ethical category of religious ethics which is grounded in religious belief such as Christian ethics of Thomas Aquinas, Islam ethics, Hindu ethics of Śaṅkara and Buddhist ethics of Nāgārjuna. Non-religious ethics is not grounded in religious doctrines, e.g., Aristotle, Immanuel Kant, or John Stuart Mill. A fundamental difference between religious and non-religious ethics is the context in which they operate. In brief, religious ethics can never be studied separately from the main ideas of the religion from which it derives. Buddhism as a religion has its own history. Grounded in the Indian tradition, Buddhism not surprisingly shares some of the worldview of that tradition. For example, Buddhism teaches that human beings are determined by their moral actions. The concept of kamma was shared by religions of ancient India at the time of the Buddha. Let us understand that meaning and vocabulary of the term “Ethics”. The term ‘Ethics’ derives from the Greek word ‘ethikos’, which pertains to ethos or character. Popularly, ethics is described as “the science treating of morals”[1] but since precise definition of the term is lacking it is necessary to state the ground that a consideration of ethics is intended to cover. G. E. Moore, in his Principia Ethica, refusing to take as adequate a definition of ethics as dealing with “the question of what is good or bad in human conduct,” declares: ”I may say that I intend to use ‘ethics’ to cover more than this-a usage for which there is, I think, quite sufficient authority. I am using it to cover the general inquiry into what is good.”[2] It is generally accepted that the word ‘ethics’ is derived from the Greek adjective ‘ethica’ which comes from the substantive ‘ethos’ which means character, custom or habit. Another synonym of ethics is the term ‘moral philosophy’, which is based on the Latin word mores, meaning habits or customs.[3] In order to grasp the full meaning of the word ethics, various opinions about the term ought to be analyzed. According to John S. Mackenzie, “Ethics…discusses men’s habits and customs, or in order to words their characters, the principles on which they habitually act, and considers what it is that constitutes the rightness or wrongness of those principles, the good or evil of those habits.”[4] William Lillie has defined ethics as “the normative science of the conduct of human beings living in societies-a science which judges this conduct to be right or wrong, to be good or bad, or in some similar way.”[5] K.N. Jayatilleke believes that “ethics has to do with human conduct and is concerned with questions regarding what is right and wrong, what is justice and what are our duties, obligations and rights” Henry Sidgwick states that “[e]thics is sometimes considered as an investigation of the true moral laws or rational precepts of conduct; sometimes as an inquiry or into the nature of the Ultimate End of reasonable human action-the Good or ‘true Good’ of man-and the method of attaining.”

In addition, Buddhist ethics like other religions’ ethics is best viewed as an ethical doctrine requiring the whole life. To be Buddhist, one needs to devote one’s life entirely. Two concepts that might be useful for clarifying this statement are being and role playing. Both of these concepts are found in daily life. This necessity of being in Buddhist ethics is a central point Buddhism teaches us to seriously examine our life, and the ethics required for this purpose can never be one based on mere role playing. Buddhism teaches much about suffering as it sees life to be nothing but suffering. Accordingly, human beings share the great task of overcoming suffering from the moment of birth. Such a task requires a radical revolution; not merely playing a role but a serious struggle. However, as Buddhist ethics contains many steps of self-cultivation, it is argued by some Buddhist scholars that sensual pleasure can be accepted in Buddhist ethics if it is considered within some lower step of the self-cultivation process. There is a Buddha saying in the Pāli canon stating that there are at least three kinds of happiness accepted in Buddhist teaching. The first is kamasukha which normally is rendered as sensual pleasure. The second is jhānasukha, usually translated as meditation happiness. The third is nibbānasukha, literally liberation happiness. The ethics taught in the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta is meant for the latter; it is presented directly for the monks, not for laymen. Buddhist ethics should be viewed as an ethical system designed for some specific religious purpose. This may be the general characteristic of religious ethics, to present the ethical principles as a means leading to the highest goal accepted in that religion. Ultimately, nibbāna is the highest objective of life in the Buddhist perspective. Some academic studies of Buddhist ethics state that nibbāna should be used as the whole criterion to judge what is good and what is not according to the Buddhist moral system. That is, whether an action is considered good or not depends on whether it leads us closer to nibbāna or not. This theory is criticized for assuming a single ethical system for all Buddhists, whether layman or monk. However, if we accept that there can be more than one system in Buddhist ethics, the criterion of nibbāna proposed above may be unsuitable. In Buddhist literature, such as the Visuddhimagga and the commentary of the Maṅgala Sutta, the Maṅgalaṭṭhadīpani, at least two kinds of ethics are mentioned: the ethics for laymen and that for monks. This theory of more than one ethical system is more flexible and in accord with the actual moral practices of Buddhist communities, both those mentioned in the texts and these that inertly exist.

For the layman, the Buddha teaches that being a good person is the aim of moral practice. The concept of the good person is mentioned through a Pāli term, kalyanaputhujana. At this level of ethics, some kind of passion, kilesa in Pāli, is permitted. From a moral perspective, these things are good or bad. The bad side of actions will not be considered because it is clear that the passion working behind these kinds of actions can never be morally justified. Only the positive aspect of passion will be examined. In brief, in lay ethics being a good person is not contrary to passion in the sense that people do not have to negate passion to be good. To accept or not accept something in Buddhist ethics relates to the ultimate objective of its ethical system. What leads the Buddha, as a young prince, to the way of the homeless ascetic is the passion to overcome the miserable facts of life: birth, old age, sickness, and death. After a time of experiments with various kinds of religious practice, Nibbāna is found by the Buddha to be the state that overcomes those miserable realities of life. Buddhism is nothing if it is not involved with nibbāna. As this world is viewed full of suffering his followers was advised by him to try to overcome suffering by a serious practice of the dhamma. The most powerful enemy of the selfpurification process is passion, regardless of the kind. However, as passion is notably varied, the follower of Buddhism seeking the final goal is achieved to deal with the lower passion first and subsequently with other passion which is more subtle and difficult to destroy.

Even though Buddhist ethics can be viewed to include two kinds of ethics, the worldly ethics (lokiyadhamma) and the transcendental one (lokuttaradhamma), these two systems are not completely separated from each other. Rather, the ethics for lay people should be seen as a lower step leading to the higher one. However, there is a notably differing view concerning the relationship between worldly ethics and transcendental ethics as to whether practicing transcendental ethics requires abandoning worldly life. Traditionally, the Buddhists in Theravāda Buddhist countries such as Thailand think that transcendental ethics cannot be practiced by a person still concerned with worldly life. It is believed that the arahant, the absolutely awakened person, must leave worldly life and take a homeless one; otherwise he must die within seven days. This understanding seems to make the two systems of Buddhist ethics unrelated to each other, as it assumes two worlds which cannot be lived in simultaneously. Moreover, this may give rise to other seriously questions such as: If one is forced to leave his daily life when his moral training has been developed to the highest point, how can Buddhist ethics claim to benefit people when it has divided a man from his life?

In a famous sutra of Mahayana Buddhism, the Vimalakirti Søtra, it is stated that the highest truth can never be contradictory. The dualistic view is considered by Mahayana Buddhism to be a contradictory concept. To divide Buddhist ethics into two categories as done in Theravada Buddhism raises the question as to whether it is based on the dualistic view or not. If the answer is yes, it can never be the highest truth. However, there are some Theravada Buddhist thinkers, e.g., Buddhadasa Bhikkhu, who believe that there can never be a contradiction in Buddhist ethics. To clarify this position, Bhikkhu defines Buddhist ethics as the ethics of thought, not of the form of life. Traditionally, Theravada Buddhist texts, especially the commentaries, stress the importance of the form of life. The monk, even though newly ordained and having lesser spiritual qualities, must be respected by lay people who are more qualified in the dhamma. This follows the concept that ethics in Buddhism is defined by the form of living. The monk is placed at the higher moral position because he is practicing the ethics of the "homeless," which is considered to be the higher form. On the contrary, in the Sutra of Hui-neng it is recorded that Huineng, the sixth patriarch of Chinese Zen Buddhism, was awarded the position of the leader of Zen when he was just a temple boy. The form of life is not important? The Zen Buddhist perspective. What does matter are that moral qualities of the mind. Hui-neng deserves the position of patriarch because his master, the fifth patriarch, understands Buddhist ethics as the ethics of the mind, not the form of living. Buddhadasa too defines Buddhist ethics as the ethics of inner qualities, not the outer form of life.

It is possible that the contradiction found in Theravada Buddhist ethics has resulted from the confusion between the Vinaya and the dhamma. Phra Dhammapitaka explains that morality in Buddhism has two major forms. In Buddhist texts the first form is called Vinaya, and the second form the dhamma. At the time that the Buddha began to pass away, he said that the Vinaya and the dhamma would be the master of the Buddhists after his departure. The Vinaya are the rules designed to be the minimum requirements for the member of Buddhist society. The five precepts, pañcaśīla in Pāli, or the 227 rules practiced by the monk are examples of the Vinaya. The essence of the Vinaya is outer control, while the dhamma is designed to give the practitioner for inner restraint. The Vinaya thus belong to the category of the ethics of outer life, while the dhamma plays the role as the ethics of inner life. The Vinaya and the dhamma play complimentary roles in Buddhist ethics. The former plays a major role in dealing with the negative passion which may cause harm to one and to others. The latter plays a basic role in dealing with the positive passion which may cause subtle suffering.

An explicit environmental ethic is not an obvious feature of the foundational documents of Buddhism in any of its traditional cultural forms. If we proceed from the assumption that the development of a Buddhism based ethic of environmental concern has significant value, an assumption endorsed by many contemporary representatives of the modernist engaged Buddhist movement.[6] As the famous Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh says, “For ethical ecologists, human exist within, are dependent upon, and are members of the web of life, the innumerable ecosystems which make up the living world, Gaia, which westerners call the environment? What is it that subtly underlines the crisis? What is our duty as Buddhists in the scheme of the environmental crisis? Can we draw inspiration from Buddhist teachings?”[7]

In fact, among the world religions, Buddhism has a great promise as a basis for an Environmental Ethics, because it teaches a concern for nature as well as our fellow human beings. Buddhism is a religion that has always presented us with tools for paying attention to our surrounding, showing us how we can take responsibility without becoming disillusioned or born out. This retreat has introduced us the aspects of Buddhist teachings and practice, which support an environmental viewpoint. The Buddha was pioneer in the world to preach love to all beings. He preached timeless message of Sacca (truth) and Ahiṃsā (Non-violence). Schumacher has admirably pointed out that a nonviolent and gentle attitude to nature is the ecological stance of Buddhism.[8] Buddhism considers the environmental crisis as an indication of the ethical crisis. The relationship of man with nature is that of symbiosis born from the realization that human being is one of the nature’s many creatures. In addition life is miracle and these miracles must be respected if there is to be peace and harmony in this world. It is living according to the noble ideals that can help us to reach the heart of the ‘Eco-Crisis’.[9] For hundreds of years, the world has respected His teachings and has been benefited by it. Only now has the world ignored the Buddhist precepts, and is paying the price. Therefore, Buddhism is full-fledged philosophy of life reflecting all aspects of experience; it is possible to find enough material in the Pāli Canon to delineate the Buddhist attitude towards nature.[10]

According to Buddhism, the restraint in sensuality imposing limitations on one’s desires will bring about environmental harmony and cause the avoidance of destruction of environmental pollution. Now it has become important to enquire how Buddhist Ethics can protect the environment. Buddhism thus needs to be re-examined in the light of current environmental crisis in the age of globalization and to generate world views and ethics which underlie fundamental attitudes and values of different cultures and societies. Today the environmental degradation has become a menace to living creatures all over the globe. The Buddha has foreseen such a crisis long ago by virtue of his deep insight. The onslaught on nature which had started with infiltration of the Aryans and the Mahājanapadas that were given shape during the time of the Buddha is becoming alarming day by day. We are often confronted by unpleasant, disagreeable and disgusting sense objects. This phenomenal world is constituted by sense organs and objects.[11] Donald Swearer goes on to say that “Compatibility between Buddhist world view and ‘an environmentally friendly’ way of living in the world. Buddhism’s traditional interdependence between human being and the natural world has been transformed to give it considerable contemporary relevance”.[12]In the Buddhist literature, many Suttas dealt with socio-economic, politico-religious and ethico-philosophical ideas of that time and also discusses about the environmental facts which are quite relevant in present days.

The Buddhist doctrines of three characteristics of things and dependent origination describe a very interesting picture of the world. In this picture, we note two important points. First, nothing seen can be said to have an essence. Second, the world of things is manifest as a unified field. These two points seem to be contradictory. The unified field mentioned in the doctrine of dependent origination implies essence, but the concept of non-substantiality mentioned in the teaching of anatta suggests something else. However, this is not a real contradiction for the doctrine of three characteristics is concerned with individual things, while the doctrine of dependent origination describes events, or the chain of things. The concept of field suggests the possibility of permanent essence. In modern physics, the universe is described through the concept of field. That is, the field is considered to be more fundamental than things. The field is permanent, while things which appear in the field are temporary. The Buddha mentions two kinds of beings. The first is the conditioned beings, saṅkhatadhamma in Pāli; and the second is the unconditioned ones, asaṅkhatadhamma in Pāli. Buddhadasa Bhikkhu notes that the doctrine of dependent origination suggests that the field of things is unconditioned being while things that play various roles within the field are temporary. We will not go beyond this observation as this is not an exploration of Buddhist metaphysics in depth. It can be concluded that the doctrines of three characteristics and dependent origination are viewed by Buddhists as providing the moral grounds used in Buddhist ethics in two ways. First, as the world has nothing worth grasping, the highest goal of life is to liberate oneself from all the illusions of the world. This may be called individual ethics, whose main objective is the cessation of suffering. The individual ethics in Buddhism is based on the doctrine of three characteristics of things and others which present a similar view, such as the doctrine of four noble truths. Second, as the world is the web of beings in which nothing can be separated from the whole, we the members of society, or the world and the universe on a larger scale, have the moral responsibilities to cooperate in promoting the welfare of all. This may be called social ethics. The social ethics in Buddhism is based on the doctrine of dependent origination. Differing from an individual ethics, social ethics aims at the cessation of the so-called social suffering instead of only individual suffering.

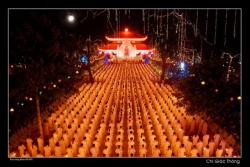

The environmental protection movement should be all-encompassing. In addition to cherishing natural resources, protecting the ecological environment, and lifestyle choices such as reducing the amount of garbage, recycling, living a pure, simple, and, frugal life, and minimizing the pollution we produce, we should further learn to respect lives and others, always reminding ourselves of this thought: apart from ourselves, there are innumerable other people; apart from our one generation, there are our innumerable descendants in future generations. In the modern world, everybody knows that we should protect our living environment, reduce the amount of garbage we produce, classify our refuse, and recycle as much as possible. Nevertheless, we are still consuming substantial amounts of energy resources every day, and producing tremendous amounts of refuse and pollution. In the former agricultural and pastoral ages, garbage could become the fertilizer and soil, returning to nature; in contrast, the natural resources consumed by the modern industrial and commercial sector are non-renewable. Contemporary civilization produces a huge amount of pollution, and this act is as horrible as generating a tremendous quantity of cancer cells in the body of Nature. We do not curse modern industry and commerce; neither do we denounce the rapid development of technological production. Therefore, we are forced to appeal to the religious and spiritual leaders of the world to advise all humankind that it must take responsibility to protect the environment while engaged in industrial, commercial, and technological activities. Human beings should not, just because of their curiosity for technological innovations and the competition of industrial and commercial wealth, keep on destroying the environment on which we rely for our survival; otherwise, humankind's history will not endure another thousand years. So, we have to appeal to the religious and spiritual leaders of the whole world not only to pray for the success of environmental work, but also to get involved personally in the all-encompassing movement of environmental concerns[13].

Environmental concern is one of the urgent problems facing mankind today. It is ironic that man is the one who pollutes his own health, and kill the life of all beings in this Earth. The risk threatening our ecology is not minor. It leads to many measures to prevent or minimize the pollution, of world-wide scale, including the ten important International Conventions to protect the environment. The awareness of protecting life and living environment has been generated in recent time. Now a question arises what is environmental ethics? Environmental ethics is a new sub-discipline of philosophy that deals with the ethical problems surrounding environmental concerns. It aims to provide ethical justification and moral motivation for the cause of global environmental concerns[14].

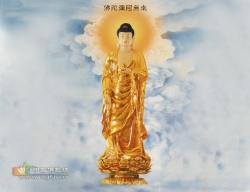

However, in Buddhism, it is one of the main basic laws which were set out by the Buddha some 25 centuries ago for his students to follow. In fact, Buddhism represents the way of compassion. The Buddha manifested a complete compassion and is respectfully seen as the compassionate protector of all beings. He taught that for those who wish to follow his Path should practice loving-kindness, not to harm the life of all beings - not only to protect mankind, but also to protect animals and vegetation. With his perfect wisdom, He saw all beings in the universe were equal in nature, and in this phenomenal world, lives of all human and animals were inter-related, mutually developing, and inseparable[15]. Buddhism is replete with perspectives on the long-term future. It stresses at every stage the fleeting nature of the present and the transitory nature of present acquisitions. With its uncompromising quest for justice, righteous conduct and nonviolence and with the spirit of universalism which pervades it, Buddhism also offers a rich reservoir of conceptual materials on all aspects of the human condition. It is wellknown that Buddhism is the most ethical of ‘religions’. The term ‘Buddhist Ethics’ first emerged as an academic discipline in 1992, with the publication of Damien Keown's book, ‘The Nature of Buddhist Ethics’. The subsequent founding of the Journal of Buddhist Ethics in 1994 further solidified the birth of a new field in the discipline of Buddhist Studies. Prior to Keown's book, only a handful of books and articles existed that attempted to delve into the questions of a specifically 'Buddhist' Ethics. Even more daunting, however, has been the separation of 'ethics' from the rest of Buddhism. Buddhism has been called an eminently ethical religion (find quote). It has also been argued, by Keown and others, that the very question the Buddha sought out to answer was a purely ethical one, namely, ‘the perennial problem of the best kind of life for man to lead’. In the Dhammapada, it is stated that one should live in the environment without causing any harm to it. “Even as a bee gathers honey from a flower and departs without injuring the flower or its colour or its flagrance, so let a sage dwell in his village”.[16] The level of contamination of waterways, air pollution and depletion of natural resources the world is facing today unprecedented in the history of human life. It has become customary to talk in terms of a crisis in matters concerning society and its relation to the natural environment.[17] The Buddha stressed the fact hat nature and human beings should be objects of unlimited kindness and benevolence and at the same time proclaims that “The forest is peculiar organism of unlimited kindness and benevolence which makes no demand for its sustenance and extends generously the products of its life activity; it affords protection to all beings, offering shade even to the examinee that destroys it.”[18] Buddhist environmental ethics is quite clear discerned from the following words of Him: It is treacherous to break the branches of a tree under whose shade one sits or sleep. Buddhism penetrates into the heart of man, making use of the environment, for example “Selo yathaa ekaghano.”[19]

The life of the Buddha is a valuable and glowing example of this. All the important events of his life like Birth, Enlightenment (Nibbāna), and passing away (Mahaparinibban) were intimately linked with flora and fauna and also during the course of his journey for more than 50 years, He spent nights under trees, preached under trees, spent most of his life in the lap of nature and there is no hesitation in declaring that the ‘nature, cradle of Buddhist culture, is a concept which in its experimental dimension has a resonance in the spiritual and aesthetic experiences of the monks’.[20] Forests, trees, wild animals, apart from the Jataka Stories are one or other way associated with the life of the Buddha. Here are some of the examples: i) Born in Lumbinivana (Lumbini forest), ii) Enlightenment (Nibbāna) under Banayan Tree (Bodhirukkha), iii) Bodhirukkha standing amidst the natural surroundings on the bank of river Niranajana, iv) Delivered His first sermon i.e. Turning of the Wheel (Dhammacakkapavattna) in Deer Park (Migadāva) at Sarnāth, v) Great Going forth or Great Demise (Mahāparinibbāna) in the Sāvana, a green forest of Mallas, vi) The Buddha learnt the stages of Dhyana from Alāra Kalāma and Uddaka Rāmaputta in the dense forest of Uruvelā (Modern Bodh Gaya), vii) He practiced austere penance for six years in the forest, viii) All the Vihāras, ārāmas, Lenas, Guhas, Hammis, etc. were located in the lap of nature and so on and on…[21]

In Buddhism, Killing or injuring living beings is regarded as both unwholesome and fundamentally immoral and that is why bhikkhu and bhikkhuμīs are even prohibited from injuring plants and seeds.[22] The ethical principle for bhikkhu / bhikkhuμī is to keep themselves away from the activities that would unintentionally injure living creatures. In Buddhism, even sprinkling water on ground considered as an offence if it is known that there are living creatures there that will be harmed by this.[23] Buddhist religious activities were directed to non-violence and non-detriment of the environment.[24] The gospel of this non-violent attitude not only covers all human beings and animals but extend towards plant kingdom as well. It is clearly mentioned in Buddhism that no one have the right to destroy plant kingdom because ‘plants are so helpful to us in providing us with all necessities of life that we are expected not to adopt a callous attitude towards them.[25]

The doctrine of dependent origination teaches that an entity does not exist and generate independently. Instead it is characterized by its fundamental interdependence and interconnectedness to all phenomena.[26] The ecological environment of today is included in the relation of space and relation of time. This means that all living things on earth are related including the circulation of organic or inorganic matter. According to the theory of Dependent Origination, everything in the universe is subject to Conditioned Arising, the natural process of law governed arising according to conditions.[27] Buddhist environmental ethics can be observed through the practical application of tenets of Dependent Origination (Paṭiccasamuppāda). It is one of the remarkable contributions of the Buddha that help us to realize the change and continuity in visualizing ecological harmony of the universe through causal changes and their respective effectuation.[28] This idea of interdependence of man and nature has been systematized in the Buddhist commentarial tradition that refers to five kinds of the cosmic laws viz. Panca Niyamadhamma: Physical Laws (Utu-niyama), Biological Laws (Bija-niyama), Society Laws (Kamma-niyama), Psychological Laws (Citta-niyama) and Moral Laws (Dhammaniyama).[29] In Buddhist ethical codes, the notion of reciprocity and interdependence also fits in with Buddhist notion of a causal system. A living entity cannot isolate itself from this causal nexus and it has no essence of its own. Reciprocity also conveys the idea of mutual obligation between man and nature and man and man.[30] One of the Sutta of Majjhima Nikaya is quite relevant here which “He who sees Dependent Origination, he sees the Dhamma, and he who discerns the Dhamma, discerns the Dependent Origination”.[31] By applying the theory into our daily life, we are certainly going to solve this grave environmental crisis.

Another teaching of the Buddha is the four noble truths based on the fundamental Buddhist theory of Dependent Origination which teaches that the existence of any single being is conditional to the existence of other beings. This concept doesn’t permit the division of nature into creatures that have instrumental or intrinsic value.[32] The four noble truths are: Dukkha, arising of Dukkha, cessation of Dukkha, and the way leading to the cessation of Dukkha. The first truth applies to the environment with recognition that environment is suffering as a whole and that serious environmental crisis is appearing locally and globally everywhere. These crises range from loss of tropical forests, plants, and animal species to global warming. The Aggannasutta makes two suggestions on this point which are[33] a) though admitting the nature’s capacity to change, it draws a direct linkage between the degeneration of natural environment and the deterioration of human morality and b) the moral deterioration is invariably linked with a tendency to resort to excessive exploitation of natural resources. The second truth is Origin of Dukkha and according to the Buddha, the desire or attachment is the source of all passions, suffering, and defilements.[34] Buddhism explains that when people indulge in immoral permissive behaviour (adhammaraga) with acquisitive completion in economic exploitation (visamalobha) ignoring moral responsibility, struggle for survival war and terrorism are the natural outcome.[35] This have enormous potential for the removal of the human caused environmental crisis and are the root cause of many social and environmental ills of global world which can only be challenged by the Four Noble Truths (cattari arya saccani) and Eightfold Path i.e. the fourth noble truth (Aṭṭhaμgikomaggo).[36] Some environmental examples of the three classic kinds of carving are:

- a) Craving for the beauty of rare plants, the tastes of exotic fish, and sexiness of fur coat,

- b) Craving to be in position of power and control over natural resources, etc. and

- c) Craving to get rid of ‘weeds’ from agricultural lands, avoid all responsibility for ecological disasters, etc.

Environmental concerns is a practice of protecting the environment, on individual, organizational or governmental level, for the benefit of the natural environment and (or) humans. Due to the pressures of population and our technology the biophysical environment is being degraded, sometimes permanently. This has been recognized and governments began placing restraints on activities that caused environmental degradation. Since the 1960s activism by the environmental movement has created awareness of the various environmental issues. There is not a full agreement on the extent of the environmental impact of human activity and concerns measures are occasionally criticized. Concerns of the environment are needed from various human activities. Waste, pollution, loss of biodiversity, introduction of invasive species, release of genetically modified organisms and toxics are some of the issues relating to environmental concerns[37].

The Buddha told us in the sutras and precepts that we should take loving care of animals, and that we should not harm the grass and trees, but regard them as the home where sentient beings lead their lives. In the stories of the Buddha's past lives, when he was following the Bodhisattva path, he was once reborn as a bird. During a forest fire, he tried fearlessly to put out the fire, disregarding his own safety by bringing water with his feathers. In the Avataṃsaka Søtra it is said that mountains, waters, grass, and trees are all the manifestation of the great bodhisattvas. So, Buddhists believe that both sentient beings and non-sentient things are all the Dharma-body of the Buddhas. Not only do the yellow flowers and green bamboo preach Buddhist teachings, but rocks can also understand Buddhist doctrines. Therefore, Buddhists regard our living environment as their own bodies. The Buddhists' life of spiritual practice is by all means very simple, frugal, and pure.

Ethics in Buddhism are traditionally based on what Buddhists view as the enlightened perspective of the Buddha, or other enlightened beings that followed him. Moral instructions are included in Buddhist scriptures or handed down through tradition. Most scholars of Buddhist ethics thus rely on the examination of Buddhist scriptures, and the use of anthropological evidence from traditional Buddhist societies, to justify claims about the nature of Buddhist ethics[38]. According to traditional Buddhism, the foundation of Buddhist ethics for laypeople is the Pañcaśīila: no killing, stealing, lying, sexual misconduct, or intoxicants. In becoming a Buddhist, or affirming one's commitment to Buddhism, a layperson is encouraged to vow to abstain from these negative actions. The precepts are not formulated as imperatives, but as training rules that laypeople undertake voluntarily to facilitate practice[39]. The term ‘pañcasīla’ is usually translated into English as ‘five precepts’, composing of abstention from killing, stealing, sexual misconduct, lying, and intoxicant drink.[40] These five precepts are generally considered as the basic code of ethical conduct for the laity. Nevertheless, they are not just the rules or commandments to be blindly followed. They require conscious and resolute performance. These five precepts however should not be followed with rigidity and dogmatism. These need to be intentionally and sedulously observed. One who always observes these five precepts is called a ‘virtuous man’, because the precepts form the characteristic trait of humanity. They form the moral nature of man distinguishing him from animals. The five precepts are also called ‘manussadhamma’ or the principle which makes a person become a complete man; they are also called ‘niccaśīla’ or the virtues to be observed always. The five precepts are as follows:

- 1. Pānātipāta Veramanī, abstention from killing any living being. This precept applies to all living beings not just humans. All beings have a right to their lives and that right should be respected.

- 2. Adinnādānā Veramanī, abstention from taking what is not given. This precept goes further than mere stealing. One should avoid taking anything unless one can be sure that is intended that it is for you.

- 3. Kāmesumicchācārā Veramanī, abstention from sexual misconduct. This precept is often mistranslated or misinterpreted as relating only to sexual misconduct but it covers any overindulgence in any sensual pleasure such as gluttony as well as misconduct of a sexual nature.

- 4. Musāvāda Veramanī, abstention from false speech. As well as avoiding lying and deceiving, this precept covers slander as well as speech which is not beneficial to the welfare of others.

- 5. Surāmerayamajjapamādaññhānā Veramanī, abstention from intoxicant drinks causing carelessness. This precept is in a special category as it does not infer any intrinsic evil in, say, alcohol itself but indulgence in such a substance could be the cause of breaking the other four precepts.

These are the basic precepts expected as a day to day training of any lay Buddhist. The five precepts can be classified under that kind of varittaśīla which means the observance of the precepts depending upon intentional abstention. According to the Pāli texts,[41] there are three kinds of ‘virati’ (abstention). The additional precepts are:

- 1. Sampatta Virati is the abstention from evil deed, as occasion arises considering one’s birth (jāti), age (vaya), education (bāhusacca), etc.

- 2. Samādāna Virati is the abstention from evil deed in accordance with one’s observances. For example, a person would intentionally abstain from killing, stealing, etc., as he observes the precepts not to kill, not to steal, etc.

- 3. Samuccheda Virati is the abstention of a noble person by completely eradicating all the roots of evil.

To find a justifiable approach to such problems it may be necessary not just to appeal to the precepts or the vinaya, but to use more basic Buddhist teachings to aid interpretation of the precepts and find more basic justifications for their usefulness relevant to all human experience. This approach avoids basing Buddhist ethics solely on faith in the Buddha's enlightenment or Buddhist tradition, and may allow more universal non- Buddhist access to the insights offered by Buddhist ethics. Kuṭadanta Sutta Buddhism points out that it is the responsibility of the government to protect trees and other organic life. It is described in the Sutta on Buddhist polity named, ‘The Ten Duties of the King.’ (Dasarājadhamma). The Kuṭadanta Sutta points out that the government should take active measures to provide concerns to flora and fauna. Pupphavagga in Dhammapada, points out that one should live in the environment without causing any harm to it. It states: ‘As a bee that gathers honey from a flower and departs from it without injuring the flower or its colours or its fragrance, the sage dwells in his village.’ The flower moreover ensures the continuity of the species and the bee in taking pollen does not interfere with nature’s design. Sutta Nipata - This contains a further expression of goodwill towards all forms of life:

“Whatever breathing creatures there may be

No matter whether they are frail or firm,

With none excepted be they long or big

Or middle-sized, or be they short or small

Or whether they are dwelling far or near

Existing or yet seeking to exist

May beings all be of a blissful heart.”

Mahāsukha Jātaka contains a poetic description of the close interrelationship between the plant and animal kingdom.

Sakka: Whenever fruitful trees abound

A flock of hungry birds is found:

But should the trees all withered be.

Away at once the birds will flee.

According to Cakkavattisīhanāda Sutta the ideal king is expected to protect not only people but quadrupeds and birds. King Asoka’s 5th Pillar Edict stating that he in fact placed various species of wild animals under concerns is one of the earliest recorded instances of a specific governmental policy of conservation.

The Buddha provided some basic guidelines for acceptable behavior that are part of the Eightfold path. The initial precept is non-injury or non-violence to all living creatures from the lowest insect to humans. This precept defines a non-violent attitude toward every living thing. The Buddhist practice of this does not extend to the extremes exhibited by Jainism, but from both the Buddhist and Jain perspectives, non-violence suggests an intimate involvement with, and relationship to, all living things[42]. An important part of the Noble Eightfold Path relates to the development of ethical conduct; for many a layperson Buddhist practice consists mainly in the ‘keeping of the precepts’; many Bhikkhus see in the Vinaya rules the essence of the religious life; and even many of the pāramitās expected of those aspiring to Buddhahood are ethical in nature. Yet to present the teaching of the Buddha as being solely and exclusively concerned with ethics could serve as detraction from the real objective of the Buddha-Dhamma, which is to serve as a path or vehicle leading to Enlightenment. While conforming to the norms of Buddhist ethics is essential for this purpose this alone will not guarantee the elimination of ignorance (avijjā), which is the real meaning of Enlightenment. The tendency of some exponents of the Dhamma to represent Buddhism as just another ethical system is misleading, especially when put before a newcomer to the Dhamma who may not be able to distinguish between Buddhist ethics and the precepts of other ethical teachers, and may conclude that Buddhism has nothing new to offer. Buddhist ethics, as formulated in the five precepts, is sometimes charged with being entirely negative. ... It has to be pointed out that the five precepts, or even the longer codes of precepts promulgated by the Buddha, do not exhaust the full range of Buddhist ethics. The precepts are only the most rudimentary code of moral training, but the Buddha also proposes other ethical codes inculcating definite positive virtues. The Maṅgala Sutta, for example, commends reverence, humility, contentment, gratitude, patience, generosity, etc. Other discourses prescribe numerous family, social, and political duties establishing the well being of society. And behind all these duties lie the four attitudes called the ‘immeasurables’ – loving-kindness, compassion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity.

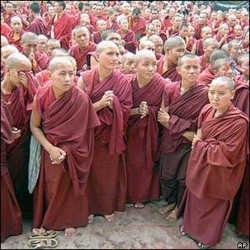

The Buddhist Saṃghas are governed by 227 to 253 rules depending on the school or tradition for Bhikkhus and between 290 and 354 rules for Bhikkhuμis. These rules, contained in the Vinaya, are divided into several groups, each entailing a penalty for their breech, depending on the seriousness of that breech. The first four rules for males and the first eight for females, known as Parājika or rules of defeat entail expulsion from the Order immediately on their breech. The four applying to both sexes are: Sexual intercourse, killing a human being, stealing to the extent that it entails a goal sentence and claiming miraculous or supernormal powers. Bhikkhuμis additional rules relate to various physical contacts with males with one relating to concealing from the order the defeat or parājika of another. Before his passing, the Buddha instructed that permission was granted for the abandonment or adjustment of minor rules should prevailing conditions demand such a change. These rules apply to all Saṃgha members irrespective of their Buddhist tradition.

Wherein, then, lies the uniqueness of Buddhist ethics? This question could be answered in many ways, but here we shall look at it from the standpoint of three criteria. First of all there are the ethical rules themselves. When we consider what actions are considered ‘good’ and what are deemed to be ‘bad’, it might appear that there is a great deal of agreement between the different ethical Systems. Such actions like killing, theft, sexual misconduct, and falsehood seem to be condemned universally. The differences emerge when we examine the question more closely, e.g. when we investigate the rationale for these rules, whether they are absolute or are relative to some other end, and so on. The rule against killing could be taken as an example. Many ethical systems proscribe only the killing of humans (i.e. murder), but Buddhism applies the rule to all sentient existence. Furthermore even in the case of humans, exceptions are sometimes allowed, e.g. for ‘holy’ or ‘just’ war. Buddhism admits of no such exemptions. In Buddhism the ethical quality of actions depends on the mental factors associated with their commission or even contemplation, and on the impact they have on the well-being of others. If action is committed with greed, aversion or delusion it is unwholesome (akusala), but the degree of moral reprehensibility (and karmic consequence) depends on a whole host of factors. Even an ‘accidental’ killing could have adverse consequences if it was caused through negligence and unmindfulness, which is a kind of ‘Delusion’ (moha). What has been said of the rule regarding killing, may also be extended to the other ethical precepts as well. Furthermore Buddhist ethics does not stop at the Five Precepts (pañca śīla), which provides only the very minimum for the proper conduct of lay persons.

In Buddhism the operation of the law of kamma is all-pervasive and universal. Its exact modus operandi is not detailed, and may not be immediately obvious. Unlike in some other versions of the karmic hypothesis, in Buddhism there is no mechanical equivalence between action and result (vipāka). As mentioned above the karmic quality of an act depends on a whole host of circumstances. In the accumulation of kammas, good and bad, the fruiting of some may be postponed or delayed while that of others could be immediate. What is certain is that the law of kamma makes divine authority, divine grace, etc. redundant. Thus in spite of superficial similarities, Buddhist ethics differs from other ethical systems when analysed in detail. In the Noble Eightfold Path the elements corresponding to morality and ethics are Right Speech, Right Action and Right Livelihood. These three together constitute śīla. The cultivation of śīla normally proceeds alongside progress in the other two great constituents of the Path, namely mental training (bhāvanā) and wisdom-insight (paññā). Because of the mutually supportive nature of the three components of morality, mental development and wisdom, it is difficult to argue about the relative importance of these three components. Nonetheless it has long been the generally accepted view that paññā is both the threshold as well as the culmination of Buddhist practice, with the other two components of śīla and bhāvanā being the chief means to the realization of this great objective.

The ethical import of this Stanza is obvious. It seems to claim that the Buddha's teaching is threefold: avoid unethical conduct, cultivate good deeds, and train one's mind. There is no question of the ethical purport of the first two postulates. ‘Training the mind’ could also be interpreted as an ethical postulate, especially when we consider the Buddhist view that evil thoughts generated by an unguarded mind are karmically effective. The last phrase of this Stanza is usually taken to mean that the three ethical postulates constitute the whole of the Dhamma. However it could be taken to mean that these ethical principles are part of the teachings of the Buddha, and not necessarily the part that constitutes the Buddha's unique discovery. In the Commentary to the Dhammapada it is stated that this and the two following Stanzas constituted the admonition (ovadagātā) delivered by the previous legendary Buddha to bhikkhus on the uposatha days. In the explanation of the meaning of the terms in this Stanza, the Commentator says that ‘to do well’ really means the ‘generation and development of skillful acts from ordination until the realization of the path of Arahat-hood’, while ‘purifying the mind’ means the elimination of the five ‘hindrances’ which are obstacles to the realization of jhānic states during meditation. All this is in keeping with the general purpose of these stanzas, which was to serve as exhortations to Bhikkhus on the uposatha day, and not to serve as a summary of the Buddha-Dhamma.

The uniqueness of Buddhist ethics lies in its many outstanding qualities. It is all embracing and comprehensive without being impractical or impossible to follow. It is free from taboos relating to diet, dress, behaviour etc. which very often pass as ethical principles. It serves the needs of the worldling as well as those of the recluse. It is useful to the rich and to the poor; to the powerful as well as to the powerless. To conform to Buddhist ethics one need not have to be a Buddhist; and it serves as a norm to measure the ethical standard of other teachings. But Buddhist ethics is only the threshold for those who wish to pursue the Buddha's path to Enlightenment and the end of all ill.

To sum up, I may say that one must promote the following four principles of environmental concerns of Dharma Drum Mountain, a small Buddhist community based in Taiwan under the leadership of Ven. Sheng-yen which in my own view is quite relevant and important one to protect our beautiful environment:

- 1) The cherishing of natural resources and the concerns of the ecological environment;

- 2) Maintaining cleanliness in family life and using daily necessities simply and frugally;

- 3) Improving interpersonal politeness and social etiquette; and,

- 4) Instead of considering everything from the standpoint of one person, one race, one time-period, and one place, we should consider it from the standpoint that all humankind of all time and space should be protected in their existence, possess the right to live, and feel the dignity of life.

In brief, the above-mentioned four kinds of environmentalism can be restated as natural environmentalism, lifestyle environmentalism, social etiquette environmentalism, and spiritual environmentalism. The environmental tasks of general people are mostly restricted to the material aspects, namely, the first and second items. The environmental tasks we carry out have to go deeper from the material level to the spiritual level of society and thinking. Environmental concerns must be combined with our respective religious beliefs and philosophical thinking into an earnest mission, so that environmentalism will not become mere slogans. So, strictly speaking, the purification of humankind's mind and heart is more important than the purification of the environment. If our mind is free from evil intentions and is not polluted by the surroundings, our living environment will also not be spoilt and polluted by us. However, for ordinary people, it is advisable to set out by cultivating the habit of protecting the material environment, and go deeper step by step until at last they can cultivate environmentalism on the spiritual level[43].

References

1. The Vinaya Piṭaka: Ed. H. Olderberg, 5 vols. London: PTS, 1879-1883. Translated references are from tr. I.B. Horner; The Book of the Discipline, 6 vols. London: PTS, 1938-1966; tr. T.W. Rhys Davids & H. Oldenberg, Vinaya Texts, Vol 13, 17, 20, SBE, reprint, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass: 1982-85.

2. The Dīgha Nikāya: Ed. T.W. Rhys Davids & J.E. Carpenter, 3 Vols. London: PTS, 1890-1911. Tr. T.W. & C.A.F. Rhys Davids; The Dialogues of the Buddha; 3 vols. 1899, 1910 & 1957 respectively (reprints), London: PTS. Also translated by M. Walshe, Thus Have I Heard: The Long Discourses of the Buddha, London: Wisdom Publications, 1987.

3. The Majjhima Nikāya: Ed. V. Trenckner & R. Chalmers, 3 vols. London: PTS, 1888-1896. Tr. I.B. Horner; The Collection of Middle Length Sayings, 3 vols. London: PTS, 1954-1959 (Reprints). Also tr. R. Chalmers, Further Dialogues of the Buddha, 2 vols, London: Sacred Books of the Buddhists Series, 1926-27; Also tr. Bhikkhu Ñāñamoli and Bhikkhu Bodhi, The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha, Boston, Mass: Wisdom Publications, 1995.

4. The Aṅguttara Nikāya: Ed. R. Morris & E. Hardy, 5 vols. London: PTS, 1885- 1900. The translated references are from The Book of the Gradual Sayings, tr. F.L. Woodward: vols. I, II & V; E.M. Hare: vols. III & IV, London: PTS, 1955- 1970 (Reprints).

5. The Saṃyutta Nikāya: Ed. M.L. Feer, 5 vols. London: PTS, 1884-1898. Tr. C.A.F. Rhys Davids and S.S. Thera, vol. I; C.A.F. Rhys Davids & F.L. Woodward vol. II; F.L. Woodward vols. III, IV, V. The Book of the Kindred Sayings; London: PTS, 1950-1956 (Reprints).

6. The Sutta-Nipāta: Eds. D. Andersen & H. Smith, reprint, London: PTS, 1984. Tr. K.R. Norman; The Group of Discourses, with alternative tr. by I.B. Horner & W Rahula, London: PTS, 1984.

7. The Dhammapada: Ed. O. von Hinüber & K.R. Norman, Oxford: PTS, 1994. Tr.

K.R. Norman, The Word of the Doctrine (Dhammapada), translated with introduction and notes, Oxford: PTS, 1997.

8. Alexander, David E., (ed.), Encyclopedia of Environmental Science, London: MPG Books, Bodmin, Corwald, 1991.

9. Banerjee, P. & Gupta, S. K., Man, Society and Nature, Shimla (India): Indian Institute of Advanced Study, 1998.

10. Batchelor, M and Brown, Kerry, (ed.), Buddhism and Ecology, Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass, 1994.

11. Batchelor, Stephen, “Images of Ecology”, in In Harmony with Nature, Buddhist Digest Series 30, Young Buddhist Association of Malaysia.

12. Boonyanate, Nuangnoi, Environmental Ethics and the Relevance of Buddhism, Asian Review, Vol. 6, 1992.

13. Chappel, Christopher Key, Non Violence to Animal, Earth and Self in Asian Traditions, Delhi: Sri Satguru Publications, 1995.

14. Chappel, Christopher Key, Ecological Prospects, Delhi: Sri Satguru Publications, 1995.

15. Dhammavihara, A Correct Vision: A Life Sublime, Kandy: Vajirama Aranya, 1990.

16. De Silva, Padmasiri, Environmental Philosophy and Ethics in Buddhism, London: Macmillan, 1988.

17. De Silva, Padmasiri, Buddhist Environmental Ethics, in Allan Badiner (ed.) Dhamma Gaia, Berkeley: Parallax Press, 1990.

18. Dutt, N., Early Monastic Buddhism, Vol. I, Calcutta, 1941.

19. Dwivedi, O. P., World Religions and Environment, New Delhi: Gitanjali Publishing House, 1989.

20. Goshling, David L., Religion and Ecology in India and South East Asia, London: Routledge, 2001.

21. Gottlieb, Roger S., ed. This Sacred Earth: Religion, Nature, Environment, Routledge, New York and London, 1996.

22. Harris, Ian, ‘How Environmentalist is Buddhism’ in Religion 21, 1991: 101-114.

23. Harris, Ian, ‘Attitude to Nature’ in Buddhism, ed. Harvey, Peter, London: 1991: 235-256.

24. Harvey, Peter, An Introduction to Buddhist Ethics, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

25. Harvey, B. A. Ronson, Love and Sympathy in Therevada Buddhism, Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass, 1980.

26. Henning, Daniel H., Buddhism and Deep Ecology, Polson, Montola: Xlibris Corporation, 2001.

27. http://www.buddhist-tourism.com/buddhism/buddhist-ethics.html

28. Humphreys, Christmas, The Wisdom of Buddhism, London: Promilla and Company, 1987.

29. Kabilsingh, Chatusmarn, Buddhist Monks and Forest Conservation, Bangkok, Thailand, 1990.

30. Keown, Damien, ed. Contemporary Buddhist Ethics, London: Curzon, 2000.

31. Kosambi, D. D., An Introduction to the Study of Indian History, Bombay: Popular Prakashan, 1975.

32. Malalasekera, G. P., Encyclopedia of Buddhism, vols. 5, Colombo: The Department of Government rinting, 1979.

33. Pathak, S. K., Buddhism and Ecology, New Delhi: Om Publications, 2004.

34. Sandell, Klas, ed. Buddhist Perspective on the Eco-crisis, Kandy: Buddhist Publication Society, 1987.

35. Sarao, K. T. S., The Origin and Nature of Ancient Indian Buddhism, Delhi: Eastern Book Linkers, 1989.

36. Schumacher, E. F., Small is Beautiful, London: Blond & Briggs, 1973.

37. Silva, Lily De, Essays on Buddhism Culture and Ecology for Peace and Survival, Dehiwala: Buddhist Cultural Centre, 2001.

38. Skolimowski, Henry K., Dharma, Ecology and Wisdom in the Third Millenium, India Delhi: Concept Publishing Company, 1999.

39. Soothill, W. E., The Lotus of the Wonderful Law, Delhi: Motilal Banarasidas, 1956.

40. Tenzin, P. Atisha, On the Environment, Dharmashala: Department of Information and Internal Relations, Central Tibetan Administration 1994.

41. Vanucci, M., Ecological Readings in the Veda: Matter-Energy-Life, New Delhi: D. K Print World Ltd. 1994.

42. Yamamoto, Shuichi, “Contribution of Buddhism to Environmental Thoughts,” in The Journal of Oriental Studies, vol. 8, 1998.

Footnotes

- ↑ H. John Muuirhead, The Elements of Ethics, London, 1910: 4.

- ↑ G. E. Moore, Principia Ethica, Cambridge University Press; Reprint 1954: 2.

- ↑ I.C. Sharma, Ethical Philosophies of India, Ghaziabad: International Publishing 1991: 31.

- ↑ John S. Mackenzie, A Manual of Ethics, Calcutta Oxford University Press, 1993: 1.

- ↑ William Lillie, An Introduction to Ethics, Delhi: Alied Publishers Limited, 1997: 1.

- ↑ Keown, Damien, ed. Contemporary Buddhist Ethics, London: Curzon, 2000:114.

- ↑ Sama, “Thoughts and Results of Earth Year 1990” in ‘In Harmony with Nature’, Buddhist Digest Series 30, Young Buddhist Association of Malaysia: 45.

- ↑ Schumacher, E. F., Small is Beautiful, London: Blond & Briggs, 1973: 41.

- ↑ Batchelor, Stephen, “Images of Ecology”, in In Harmony with Nature, Op. Cit.: 47.

- ↑ Batchelor, Stephen & Brown, Kerry, ed. Buddhism and Ecology, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1994: 18.

- ↑ M.I.236.

- ↑ Goshling, David L., Religion and Ecology in India and South East Asia, London: Routledge, 2001:168.

- ↑ http://greentheme.blogspot.com/2007/08/buddhism-environmental-protection.html (Extracted on April 15, 2010).

- ↑ Tongjin Yang, ‘Towards an Egalitarian Global Environmental Ethics’ Environmental Ethics and International Policy , ISBN 978-92-3-104039-9 © NESCO 2006, p. 23.

- ↑ http://www.buddhanet.net/budsas/ebud/ebdha006.htm (Extracted on April 15, 2010).

- ↑ Dhp. V.6.

- ↑ Sandell, Klas, Op. Cit. : 1.

- ↑ Dhammavihara, A Correct Vision: A Life Sublime, Kandy: Vajirama Aranya, 1990: 17.

- ↑ Dhp.V.81.

- ↑ De Silva, Padmasiri, Environmental Philosophy and Ethics in Buddhism, London: macmillan, 1988:125.

- ↑ Pathak, S. K., Buddhism and Ecology, New Delhi: Om Publications, 2004: 51-52 & 58-59.

- ↑ Vinaya Pitaka. V. 34; Digha Nikaya. I. 64.

- ↑ Ibid. IV. 48-49.

- ↑ Digha Nikaya. I. 182.

- ↑ Sandell, Klas, Op. Cit.:19.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Harvey, Peter, An Introduction to Buddhist Ethics, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000: 152.

- ↑ Pathak, S. K., 2004, Op. Cit.: 8.

- ↑ Atthasalini, PTS, 1920-21: 8.

- ↑ A.I.160, Sandell, Klas, Op. Cit. : 1.

- ↑ M.I.236-237.

- ↑ Henning, Daniel H., Buddhism and Deep Ecology, Polson, Montola: Xlibris Corporation, 2001: 22.

- ↑ Ibid,: 58.

- ↑ Henning, Daniel H., Op. Cit.: 21.

- ↑ A.I.160.

- ↑ Goshling, David L., Op. Cit.,: 84.

- ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Environmentalprotection (Extracted on April 15, 2010).

- ↑ Damien Keown The Nature of Buddhist Ethics Macmillan 1992; Peter Harvey An Introduction to Buddhist Ethics, Cambridge University Press 2000.

- ↑ Stewart McFarlane in Peter Harvey, ed., Buddhism. Continuum, 2001, p. 187.

- ↑ D. III. 235: A. III. 203, 275; Vbh. 285.

- ↑ DA. I. 305; KhpA. 142; DhsA. 103.

- ↑ Carl Olson, The Different Paths of Buddhism p.73.

- ↑ http://greentheme.blogspot.com/2007/08/buddhism-environmental-protection.html (Extracted on April 15, 2010).

Source

Submitted by: Dr. Arvind Kumar Singh