The Household Butsudan

The faith of a lay Shingon Buddhist practitioner consists of daily practice, offerings, and meditating on the Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Wisdom Kings, and ancestors. In Japan, there is almost always an altar in the homes of Buddhist believers. The Butsudan plays a role that is central to the spiritual aspect in the household. Sometimes it will come in the form of a box-like altar with small steps inside for placing offerings, spirit tablets, and of course a platform for Buddha scrolls/statues, others may be a simple table with offerings placed before the images.

In Buddhist faith, it is not considered to be idol worship of a certain deity, but rather these images and offerings made sincerely should be viewed as symbolic reminders of the qualities inherent not only in the Buddha, but in all beings. Thus, when a Buddhist kneels, places hands in gassho (hands joined), he or she does not worship the holy image, but brings to mind the teaching of the enlightened one who has taught the way to liberation.

For Shingon Buddhist altars, it is best to have it facing south, as there are certain energies that can be channeled through this direction. It is also fine to have the altar to face the east, as it is believed that Yakushi Nyorai, the Medicine Buddha, abides in the Pure Land of the East.

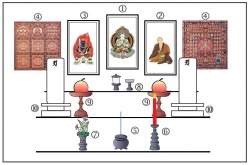

1. Mahavairocana Tathagata (Dainichi Nyorai), the center of the altar, considered the honzon (main Buddha) of Shingon Buddhism. The main meditative deity for the practitioner.

2. Kobo Daishi (Kukai), left to the honzon, the founder of the Shingon Buddhist school, eighth patriarch of the Esoteric Buddhist lineage.

3. Acalanatha Vidyaraja (Fudo Myoo), right of the honzon, a fearsome yet compassionate and protective deity, thus he is usually the first of the Thirteen Buddhas.

4. The Vajradhatu (left) and Garbhakosa (right) mandalas, the essence of Shingon Buddhist teachings. Maps out the spiritual and physiical world of the Buddhas, bodhisattvas, wisdom kings, and heavenly beings. These can be placed on the side walls if the altar is a traditional Butsudan, or if it is a table altar with no doors, they can be placed on each side.

5. Incense burner (center) a symbol of the perfection of diligence. Incense smoke always travels in a straight line when stuck in a censer, it also permeates the air with a sweet scent, a reminder of how pervasive the precepts can be.

6. Candle (right), a symbol of the perfection of wisdom. In the last sermon of Shakyamuni Buddha, he exhorted to his disciples to be “lamps among themselves”, reminding them not to be attached to the teacher, but rather uphold the teachings as the teacher.

7. Flowers (left), a symbol of the perfection of patience, as flowers, which are one of the most beautiful things on earth, take many days or months to grow and blossom. The flowers can also represent the impermanence in all things living.

8. Tea and rice, a food offering to the Buddhas. We eat food at three periods of the day, but it should be sufficient to make a small offering to the Buddhas at the morning and taken down in the afternoon. It represents the perfection of meditation as it can be impossible to settle down without food in our stomachs.

9. Fruit, another food offering to the Buddha, and a symbol of the fruit of attainment of enlightenment.

10. Ihai (spirit tablets), housing the spirits of those who have gone onto the next plane of existence. Generally in some sects, it is not allowed to have a spirit tablet inside a Butsudan as one cannot offer a dead person to the Buddha, but it can be said in Shingon that even in death, a person can still strive to become a Buddha within their own body, thus releasing them from the cycle of samsara.