The Three Realms

by Arnie Kozak, Ph.D.

According to Buddhist cosmology, there are three realms — or types — of existence: the Realm of Desire, the Realm of Form, and the Realm of No-Form. These realms can be understood as the fruits of meditative experiences or the jhanas (meditative states). There are eight jhanas corresponding to the three realms. If you are in the realm of desire, you have not yet reached the first meditative state. The realm of form corresponds to meditative states one to four, and the realm of no-form corresponds to the highest meditative states (five through eight).

The realm of desire will be explored in detail below. It includes the Wheel of Life and is a potent metaphor for karma, suffering, and the motivation to get beyond The Three Poisons of greed, hatred, and delusion to the liberation of nirvana.

The Realm of Form

The realm of form (rupa) and its corresponding meditative states can be understood through the metaphor of the “higher gods.” These meditative states correspond to contact with the form of the body and are the basis for vipassana meditation. They can also refer to forms of meditation that involve visualization.

The Form jhanas are:

Rapture and Pleasure Born of Seclusion

Rapture and Pleasure Born of Concentration

Equanimity and Mindfulness with Pleasant Abiding

Equanimity and Mindfulness, Neither Pleasure Nor Pain

Thanissaro Bikkhu presents the jhanas in The Paradox of Becoming. The Buddha said, “Then quiet secluded from sensuality, secluded from unskillful mental quality, he enters and remains in the first jhana: rapture and pleasure born of seclusion, accompanied by directed thought and evaluation.” The first jhana provides the foundation for the next. The Buddha said, “Rapture and pleasure born of concentration, unification of awareness free from directed thought and evaluation — internal assurance.” The second jhana gives way to the third, “Then with the fading of rapture, he remains equanimous, mindful, and alert, and senses pleasure with the body. Equanimous and mindful, he has a pleasant abiding.” He goes on to describe the fourth jhana, “Then with the abandoning of pleasure and pain, he enters and remains in purity of equanimity and mindfulness, neither pleasure nor pain. He sits permeating the body with a pure, bright awareness.”

The Realm of No-Form

To reach the highest jhanas is to reach the realm of no-form (arupa).

Recall, however, from Siddhartha's story that he had attained the highest jhanas while meditating with his teachers Alara Kalama and Udraka Ramaputra. Once he came out of these rarified and sublime states he found himself right back into samsara. So even though these states are delightful, they do not represent liberation. Nirvana is not a state of meditation, but a release from all conditioned and constructed existence.

These meditative states are based on profound concentration, and the Buddha described these states as, “the complete transcending of perceptions of form, with the disappearance of perceptions of resistance.” The practitioner will experience “infinite space” and will then transcend infinite space into “infinite consciousness.” And from infinite consciousness the practitioner will transcend into the “dimension of nothingness.” But you're not done yet! This dimension of nothingness itself is transcended, and the practitioner will experience the dimension of “neither perception or nonperception.” These states correspond to the jhanas five through eight.

The Formless jhanas are:

Infinite Space

Infinite Consciousness

Nothingness

Neither Perception Nor Non-Perception

The Realm of Desire

Within the Realm of Desire there are six categories into which you can be born in any given moment. These realms comprise a circle; one is not “higher” than the other. These represent states, momentary and more permanent, that you may find yourself in at any given moment. Psychoanalyst and Buddhist practitioner Mark Epstein presents the traditional Buddhist Wheel of Life as a model for the neurotic mind. Each of the six realms depicted in this model can be understood as a state that you will experience at some point, perhaps many points in your life. In the very center of the wheel, at the hub of the wheel, are three animals representing the three poisons (kleshas):

Greed or desire is represented by the rooster

Hatred or anger is represented by the snake

Delusion or ignorance is represented by the pig

The six realms are:

The God Realm

The Human Realm

The Realm of Jealous Gods (Titans)

The Animal Realm

The Realm of Hungry Ghosts

The Hell Realm

Whether or not you end up as a god or a hungry ghost largely depends on your karma, your intentions and actions. Nirvana is beyond these realms and is thus the attractive appeal of awakening, enlightenment, or liberation.

According to John Snelling in The Buddhist Handbook, the most fortunate age to be born in is termed a Bhadra Kalpa. During a Bhadra Kalpa, at least 1,000 Buddhas will be born (over the course of 320,000,000 years). Each Buddha will discover the dharma, and teach it for anywhere from 500 to 1,500 years, until a dark age sets in and the teaching is lost. Humanity is currently in a Bhadra Kalpa now.

The Realm of Desire is named so because it is the realm in which beings perceive objects through their senses and experience desirability or undesirability. Desire is the root of suffering, and there is much suffering in the Realm of Desire. The Realms of Form and No-Form are not subject to the same experiences.

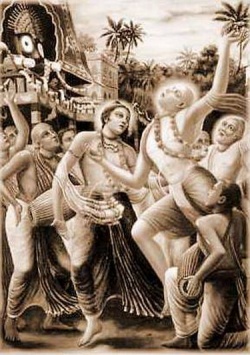

The God Realm

According to Mark Epstein, the God Realm is “inhabited by beings with subtle bodies, not prone to illness, who delight in music and dance and exist in extended version of what has come to be called peak experiences, in which the participant dissolves into the experience of pleasure, merging with the beloved and temporarily eradicating the ego boundaries.” In other words, this is a state that feels good but is temporary. There may be twenty-six “mansions” in the god realm, but there is a tendency to become complacent here. If life were all pleasure and bliss, where would the motivation for transcendence come from? This realm also tends to be rather self-absorbed (no bodhisattvas here), and suffering persists, albeit in a subtle way.

Realm of Jealous Gods (Titans)

According again to Dr. Epstein, the jealous gods “represent the energy needed to overcome a frustration, change a situation, or make contact with a new experience.” This is the realm of ego, mastery, and striving. For example, the jealous gods can overtake your meditation practice in an egodriven way, and this remains a pitfall. Striving cannot be overcome with striving. In other words, you can get caught in the trap of desiring more and more pleasurable meditation experiences. You may have had a taste of one of the jhanas and now your mind is fixated on having that experience again. Sometimes the jealous gods are portrayed as titans, warrior demons (asuras), which have taken their human traits and used them in the pursuit of power. They are always in foul temper, always causing trouble for someone, and do not symbolize rest or peace.

Animal Realm

In the animal realm, you are caught up in desire and instinct, especially sexuality and the pleasures of the senses. It is a realm without awareness and states that are probably all too familiar to you. Animals are trapped in ignorance, and have no way of getting out of their instinct-driven behaviors. The animal realm is pure desire and tinged with the suffering that comes with desire.

“Never forget how swiftly this life will be over, like a flash of summer lightning or the wave of a hand. Now that you have the opportunity to practice dharma, do not waste a single moment on anything else.” — Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche

The traditional Buddhist view is that animals do not have sufficient awareness to generate good karma (due to the lack of conscious intentionality). “Does a dog have Buddha-nature?” is a question that divides Buddhists. Again, metaphorically, the animal, like the state of passion, is probably quite familiar to you.

Realm of Hungry Ghosts

The forth realm is restless spirits (pretas). Hungry ghosts are the most interesting form of preta. The hungry ghost has a pinhole mouth and a huge stomach and is therefore never satisfied. Adequate amounts of food can never pass through their small mouths and the narrow necks, and when it does, immense pain is experienced. This can be seen as a metaphor for greed that takes the form of excessive desire.

For instance, if you try to find happiness through having material things, this can become a futile pursuit. The more you have the more you want. That is like being a hungry ghost. A materialistic guru once said, “To become one with everything you need to have one of everything.” But can this really provide happiness? Research suggests that material wealth beyond a certain point of providing for basic needs does not lead to happiness. If taken literally, if you are not generous in this lifetime you may be reborn as a hungry ghost. Fortunately, traditional Buddhists set out food from their meals to “feed” hungry ghosts. Some Buddhist festivals in Asia aim to take care of the hungry ghosts who are suffering as a result of their bad karma.

There is an episode of South Park that features one of its eight-year-old characters, Cartman, pacing in front of a game store awaiting the release of the new Wii. Unfortunately for him (and everyone around him), the Wii won't be released for another three weeks. Cartman grunts, “Come on…Come on…How much longer?” He bemoans his fate, “Time is slowing down. It's like waiting for Christmas, times a thousand.” Cartman is a hungry ghost!

Hell Realm

Fear, even to the point of paranoia, can characterize the hell realm. It's not the place you want to be. Early Buddhists, just like everyone else, had vivid imaginations when it came to suffering and torture. Metaphorically, you could be endlessly cut up, burned, frozen, eaten, beaten, or tortured in any number of ways, only to die and wake up and do it all over again. Some areas of hell contain abominable nightmares, unbearable sensory experiences, and horrible visions. The denizens of hell symbolize hatred, and the pervasive self-inflicted anxiety of dukkha. There are as many as ten hells in the Realm of Desire, and the inhabitants must make their way through all in order to escape the anguish and suffering. There are realms where you may be hot (eight of those) or cold (also eight of those), or where you may be lacerated, or eaten alive. Take your pick!

The third realm is the demon (asura), a state dominated by anger. In Asia, however, these demons may not be regarded metaphorically. Evil spirits can wreak havoc or cause mischief.

Human Realm

The human form, on the other hand, is a very desirable realm to inhabit. It could be said to be the center of everything in the Buddhist cosmos. It is within the human form that you have your only chance for enlightenment and escape from samsara. In any given moment you can be in any of the realms, depending upon your actions and intentions. One way to think about samsara is the endless cycling between these realms of experience. The human realm contains the seed of its own awakening.

Although humans still have some very negative traits, they are free from the extreme negativities of life as a hungry ghost, animal, or hell-being. Humans have the capacity to do right and wrong; it is therefore in the human realm that positive or negative actions are performed. This is state where your karma gets played out. Buddhists who take rebirth literally see the human realm as the only realm that can influence its future rebirth.

Buddhist cosmology mentions three realms (or reigns, or worlds, or spheres) of existence, each one referring to a specific kind of rebirth connected with the fruits of the attainment of a meditative state (pali: jhāna, sanscrit: dhyāna).

The picture of the world presented in Buddhist cosmology cannot be taken as a literal description of the shape of the universe from an ordinary point of view. Rather, it is the universe as seen through the eyes of a Buddha, since an enlightened being can perceive all of the other worlds and the beings born, risen up and passing away within them.

DESIRE REALM (kāmadhātu)

The beings born in the Kāmadhātu differ in degree of happiness, but they are all, other than arhats and Buddhas, under the domination of Māra and are bound by sensual desire, which causes them suffering. Within the desire world are either five or six realms of existence representing different kind of suffering (in Theravada tradition for example there are only five realms, because the domain of the asuras is not regarded as separate from that of the devas).

FORM REALM (rupadhātu)

It’s the first of the physical realms though the bodies of its inhabitants are composed of a subtle substance which is invisible to the inhabitants of the Kāmadhātu. The dwellers in the form realms have minds corresponding to the four lower meditative states (rupadhyānas). There are five form realms, the first four corresponding to the four types of rupadhyānas:

BRAHMĀ WORLDS The mental state of the devas of the Brahmā worlds corresponds to the first meditative state, and is characterized by observation and reflection as well as delight and joy. The Buddha said about this state: “Quiet secluded from sensuality, secluded from unskillful mental quality, he enters and remains in the first jhana (pali for dhyāna, the meditative state): rapture and pleasure born of seclusion, accompanied by directed thought and evaluation”.

ĀBHĀSVARA WORLDS

The mental state of the devas of the Ābhāsvara worlds corresponds to the second meditative state, and is characterized by delight as well as joy. These devas are said to have bodies that emit flashing rays of light like lightning. The Buddha described this state as “rapture and pleasure born of concentrationn of awareness free from directed thought and evaluation, internal assurance.”

ŚUBHAKṚTSNA WORLDS The mental state of the devas of the Śubhakṛtsna worlds corresponds to the third meditative state, and is characterized by a quiet joy. These devas have bodies that radiate a steady light. About the spiritual practitioner who entrers this meditative state the Buddha said: “Then with the fading of rapture, he remains equanimous, mindful, and alert, and senses pleasure with the body. Equanimous and mindful, he has a pleasant abiding.”

BṚHATPHALA WORLDS The mental state of the devas of the Bṛhatphala worlds corresponds to the fourth meditative state, and is characterized by equanimity. About the spiritual practitioner who entrers this meditative state the Buddha said: “Then with the abandoning of pleasure and pain, he enters and remains in purity of equanimity and mindfulness, neither pleasure nor pain. He sits permeating the body with a pure, bright awareness.”

ŚUDDHĀVĀSA WORLDS This world are said the “Pure Abodes” and they are distinct from the other worlds of the form because in Śuddhāvāsa don’t live devas who have been born there through ordinary merit or meditative attainments, but only those Non-returners (Anāgāmins) who are already on the path to Arhat-hood (the state of a spiritual practitioner who has realized certain high stages of attainment) and who will attain enlightenment directly from the Śuddhāvāsa worlds without being reborn in a lower plane (even if Anāgāmins can also be born on lower planes). Every Śuddhāvāsa deva is therefore a protector of Buddhism. No Bodhisattva is ever born in these worlds, because a Bodhisattva must ultimately be reborn as a human being.

FORMLESS REALM (Ārūpyadhātu)

The formless realm would have no place in a purely physical cosmology, as none of the beings inhabiting it has either shape or location. In this realm live those devas who attained one of the four Formless Absorptions of the ārūpadhyana (the four higher meditative states) in a previous life, and now enjoys the fruits of the good karma of that accomplishment. Bodhisattvas are never born in the Ārūpyadhātu even when they have attained the arūpadhyānas. There are four types of Ārūpyadhātu devas, corresponding to the four types of arūpadhyānas:

ĀKĀŚĀNANTYĀYATANA This world is also said the ”Sphere of Infinite Space”. In this sphere formless beings dwell meditating upon space or extension as infinitely pervasive.

VIJÑĀNĀNANTYĀYATANA This world is also said the ”Sphere of Infinite Consciousness”. In this sphere formless beings dwell meditating on their consciousness as infinitely pervasive.

ĀKIṂCANYĀYATANA This world is also said the ”Sphere of Nothingness” (literally “lacking anything”). In this sphere formless beings dwell meditating upon the thought that “there is no thing“. This is considered a form of perception (samjñā), though a very subtle one.

NAIVASAṂJÑĀNĀSAṂJÑĀYATANA This world is also said the ”Sphere of Neither Perception nor Non-Perception”. In this sphere the formless beings have gone beyond a mere negation of perception and have attained a state where they do not engage in perception (samjñā) but are not wholly unconscious.