Four Truths

The Disease, the Cause, the Cure, the Medicine The orientation of the Buddha's teaching What did the Buddha teach? The early siitras present the Buddha's teaching as the solution to a problem. This problem is the fundamental problem of life. In Sanskrit and Pali the problem is termed du/:lkha/dukkha, which can be approximately translated as 'suffering'. In a Nikaya passage the Buddha thus states that he has always made known just two things, namely suffering and the cessation of suffering.1 This statement can be regarded as expressing the basic orientation of Buddhism for all times and all places. Its classic formulation is by way of 'four noble truths': the truth of the nature of suffering, the truth of the nature of its cause, the truth of the nature of its cessation, and the truth of the nature of the path leading to its cessation. One of the earliest summary statements of the truths is as follows:

This is the noble truth of suffering: birth is suffering, ageing is suffering, sickness is suffering, dying is suffering, sorrow, grief, pain, unhappiness, and unease are suffering; being united with what is not liked is suffering, separation from what is liked is suffering; not to get what one wants is suffering; in short, the five aggregates of grasping are suffering. This is the noble truth of the origin of suffering: the thirst for repeated existence which, associated with delight and greed, delights in this and that, namely the thirst for the objects of sense desire, the thirst for existence, and the thirst for non-existence. This is the noble truth of the cessation of suffering: the complete fading away and cessation of this very thirst-its abandoning, relinquishing, releasing, letting go.

This is the noble truth of the way leading to the cessation of suffering: the noble eightfold path, namely right view, right intention, right 6o Four Truths speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, right concentration.2 The temptation to understand these four 'truths' as functioning as a kind of Buddhist creed should be resisted; they do not represent·'truth claims' that one must intellectually assent to on becoming a Buddhist.

Part of the problem here is the word 'truth'. The word satya (Pali sacca) can certainly mean truth, but it might equally be rendered as 'real' or 'actual thing'. That is, we are not dealing here with propositional truths with which we must either agree or disagree, but with four 'true things' or 'realities' whose nature, we are told, the Buddha finally understood on the night of his awakening. The teachings of the Buddha thus state that suffering, its cause, its cessation, and the path to its cessation are realities which we fail to see as they are, and this is as true for the 'Buddhist' as the 'non-Buddhist'.

The 'Buddhist' is simply one committed to trying to follow the Buddha's prescriptions for coming to see these realities as they are. This is not to say that the Buddha's discourses do not contain theoretical statements of the nature of suffering, its cause, its cessation, and the path to its cessation, but these descriptions function not so much as dogmas of the Buddhist faith as a convenient conceptual framework for making sense of Buddhist thought.3 Thus from one point of view any piece of Buddhist theory can be considered as to do with the analysis of one or other of the four truths. The disease of suffering The starting point of the Buddha's teachings is, then, the reality of suffering.

Yet the summary statement of the first truth quoted above should not be seen as seeking to persuade a world of otherwise perfectly contented beings that life is in fact unpleasant. Rather it addresses a basic fact of existence: sooner or later, in some form or another, no matter what they do, beings are confronted by and have to deal with duf:tkha. This is, of course, precisely the moral of the tale of the Buddha's early life in Kapilavastu: even with everything one could possibly wish for, he had not found true happiness as long as he and those dearest to him were prey to disease, old age, and death.

This is the actuality of dul:zkha. Rich in meaning and nuance, the word du/:lkha is one of the basic terms of Buddhist and other Indian religious discourse. Literally 'pain' or 'anguish', in its religious and philosophical contexts dul:zkha is, however, suggestive of an underlying sense of 'unsatisfactoriness' or 'unease' that must ultimately mar even our experience of happiness. Since any pleasant experience, whatever its basis, is ultimately unreliable and subject to loss, if we rest our hopes of final happiness in it we are bound to be disappointed. Thus dul:zkha can be analysed in Buddhist thought by way of three kinds: suffering as pain, as change, and as conditions.

The first is self-evident suffering: when we are in mental or physical pain there is no question that there is dul:zkha. Yet when we are enjoying something, or even when there is nothing that is causing us particular unhappiness, things are always liable to change: what we were enjoying may be removed from us or something unpleasant may manifest itself-this is dul:zkhq as change. In fact everything in the world, everything we experience, is changing moment by moment. Some things may change very rapidly, some things extremely slowly, but still everything changes, everything is impermanent (anitya!anicca).

When we begin to be affected by the reality of this state of affairs we may find the things that previously gave us great pleasure are tainted and no longer please us in the way they once did. The world becomes a place of uncertainty in which we can never be sure what is going to happen next, 'a place of shifting and unstable conditions whose very nature is such that we can never feel entirely at ease in it. Here we are confronted with du/:lkha in a form that seems to be inherent in the nature of our existence itself-dul:zkha as conditions.

To put it another way, I may be relaxing in a comfortable armchair after a long, tiring day, but part of the reason I am enjoying it so much is precisely because I had such a long, tiring day. How long will it be bef9re I am longing to get up and do something again-half an hour, an hour, two hours? Or again, I may feel myself perfectly happy and content; the suffering I hear about is a long way away, in another town, in another country, on another continent. But how close does it have to come before it in some sense impinges on my own sense of well-being-the next street, the house next door, the next room?

That is, we are part of a world compounded of unstable and unreliable conditions, a world in which pain and pleasure, happiness and suffering are in all sorts of ways bound up together. It is the reality of this state of affairs that the teachings of the Buddha suggest we each must understand if we are ever to be free of suffering. On the basis of its analysis of the problem of suffering, some have concluded that Buddhism must be judged a bleak, pessimistic and world-denying philosophy. From a Buddhist perspective, such a judgement may reflect a deep-seated refusal to accept the reality of du}:tkha itself, and it certainly reflects a particular misunderstanding of the Buddha's teaching. The Buddha taught four truths and, by his own standards, the cessation of suffering and the path leading to its cessation are as much true realities as suffering and its cause.

The growth of early Buddhism must be understood in the context of the existence of a number of different 'renouncer' groups who shared the view that 'suffering' in some sense characterizes human experience, and that the quest for happiness is thus only to be fulfilled by fleeing the world. Some historians have felt that the emergence of such a view and its general acceptance in eastern India of the fourth and third centuries BCE requires a particular kind of explanation.

In short, there must have been a lot of suffering about. Various suggestions have been made, from psychological unease caused by urbanization to the spread of disease. 5 Whether or not such factors played a role, I am unconvinced that as historians we are driven to seek $Uch explanations, for this is to conclude that the decisive historicaldeterminants in this case are the physical and mental well-being of society at large; rather than individual personalities.

An individual's sense of suffering need not be related to the amount of suffering in society as a whole, nor even to the amount of suffering he or she has personally undergone. Nor am I convinced that the idea that suffering _in some sense characterizes human experience is so extraordinary and culturally specific that it requires particular explanation; the ancient Indian sage might protest with some justification: Thou seest we are not all alone unhappy: This wide and universal theatre Presents more woeful pageants than the scene Wherein we play in.6 Historians seem prepared to accept that the Buddha was a charismatic personality and something of a genius.

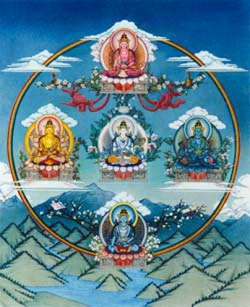

That such an individual might well have had a certain success in convincing others of the soundness of his understanding of the nature of the world, and that they in turn might have had considerable influence on the overall cultural outlook does not seem to me historically implausible. It is worth noting, however, that the Buddhist tradition itself makes certain observations concerning the circumstances in which beings will be receptive to the teaching of dul:zkha. According to the understanding of traditional Buddhist cosmology the universe comprises many different types of beings. Some of these beings' lives are so pleasurable that, although it is not impossible for them to appreciate that their happiness is not final or absolute, it is certainly difficult. On the other hand, other beings are preoccupied with lives of such misery that coming to understand the subtlety of the Buddha's teaching is extremely difficult.

According to the ancient commentary to the Jiitaka, it was the consideration of the circumstances in which beings would be receptive to his teachings that the Bodhisattva took into account when he was reflecting in the Tu~ita heaven on when and where to be reborn for the last time and become a buddha and teach Dharma.7 The Buddhist tradition has sometimes compared the Buddha to a physician and the four truths to a medical diagnosis: the truth of du/:lkha is like a disease, the truth of the origin of du/:lkha is like its cause, the truth of the cessation of du/:lkha is like the disease's being cured, and the truth of the path leading to the cessation of du/:lkha is like the medicine that brings about the disease's cure.8 It is the wish to relieve the suffering of the disease and eradicate its cause that is the starting point of Buddhist practice.

All this suggests something else that is fundamental to the orientation of Buddhist thought and practice: the wish to relieve suffering can in the end only be rooted in a feeling of sympathy (anukampii) or compassion for the suffering of both oneself and of others. This feeling of sympathy for the suffering of beings is what motivates not only the Buddha to teach but ultimately everyone who tries to put his teaching into practice.9 The Buddha's teaching thus represents the medicine for the disease of suffering. Or, according to the metaphor of the fourth truth, it is the 'path' (miirga/magga) or 'way' (pratipad!pa{ipadii) that one follows in order to reach the destination that is the cessation of suffering. Or, as we saw in the previous chapter, it is a system of training in conduct, meditation, and wisdom. If one were to define Buddhism in keeping with this understanding, it would have to be as a practical method for dealing with the reality of suffering.

Yet it is usual to classify Buddhism as 'a religion'. Asked to define the meaning of the word religion, English speakers would probably not immediately suggest 'a practical way of dealing with the reality of suffering'. Certainly this is not the kind of definition we find in contemporary dictionaries. Yet in the Indian cultural context this is essentially how many of the traditions which we today generally class as 'religious' conceive of themselves.

One of the ancient and recurring images of Indian religious discourse is of 'crossing the ocean of existence', that is, crossing over from the near shore, which is fraught with dangers, to the further shore, which is safe and free from danger. This is equivalent to escaping or transcending the endless round of rebirth that is smpsiira and the condition of dul:zkha. One contemporary dictionary definition of religion is as follows: 'belief in, worship of or obedience to a supernatural power or powers considered to be divine or to have control over human destiny' .

This is illustrative of a modern tendency to understand religion as principally a kind of belief system-usually revolving around a God who is both creator and saviour-that an individual takes on board and which then provides him or her with a way of looking at the world. Probably the reduction of religion to this kind of belief system should be seen as a relatively recent phenomenon---,-the legacy of the Reformation and the Enlightenment.

Protestant theology tended to emphasize the primacy of 'faith' over 'works'; by seeming to expose the irrationality of the theoretical beliefs regarded as the underpinnings of this Christian faith, the post-Enlightenment traditions of philosophy and science appeared about to cause the collapse of religion. All this amounts to a modern preoccupation with particular beliefs as the essence of religion. Arguably the very nature of Christianity makes it predisposed to understanding itself as a particular set of beliefs; nevertheless historically Christianity has clearly been much more than its creeds-as much a question of adopting certain practices as of adopting beliefs.

Theoretically the modern aqtdemic study of religion should have made us all aware of the multi-dimensional nature of religion, but cultural biases are not so easily corrected in practice.11 Thus the tendency to understand religion as primarily involving the adoption of particular kinds of beliefstill informs what we expect 'religions' to be; this hinders our understanding of Christianity, let alone of Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism. I am not concerned here to pronounce on a question that is sometimes asked of Buddhism: is it a religion? Obviously it depends on how one -defines 'a religion'.

What is certain, however, is that Buddhism does not involve belief in a creator God who has control over human destiny, nor does it seek to define itself by reference to a creed; as Edward Conze has pointed out, it took over 2,ooo years and a couple of Western converts to Buddhism to provide it with a creed.U On the other hand, Buddhism views activities that would be generally understood as religious-such as devotional practices and rituals-as a legitimate, useful, and even essential part of the practice and training that leads to the cessation of suffering.

Buddhism regards itself as presenting a system of training in conduct, meditation, and understanding that constitutes a path leading to the cessation of suffering. Everything is to be subordinated to this goal. And in this connection the Buddha's teachings suggest that preoccupation with certain beliefs and ideas about the ultimate nature of the world and our destiny in fact hinders our progress along the path rather than helping it. If we insist on working out exactly what to believe about the world and human destiny before beginning to follow the path of practice we will never even set out. An important incident is related in the Cu!a-Miilulikya Sutta ('short discourse to Malmikya') and concerns ten matters that are 'unexplained' or 'undetermined' (avyiikrta/avyiikata) by the Buddha.B

These ten undetermined questions are as follows: (1) is the world eternal or (2) is it not eternal? (3) is the world finite or (4) is it infinite? (5) are the soul and the body one and the same thing or ( 6) is the soul one thing and the body another? (7) after death, does the Tathagata (i.e. a buddha or arhat) exist or (8) does he not exist or (9) does he both exist and not exist or ( 10) does he neither exist nor not exist? One evening, it seems, the monk Malmikyaputta felt that he had been patient with the Buddha long enough. Malmikyaputta went to the Buddha and declared that unless he answered these questions or· straightforwardly stated that the reason he did not answer them was because he did not know the answers, he would abandon his training under the Buddha. The Buddha responded by asking Malmikyaputta a question: had he ever said to Malmikyaputta that he should come and practise the spiritual life with him and he would explain to him whether or not the world was eternal?

Malmikyaputta confessed that he had not. The Buddha then suggested that whoever declared that he would not practise the spiritual life with the Buddha until he had explained these questions would certainly die without the Buddha having explained them; he then related a story of a man struck by an arrow. It is as if there were a man struck by an arrow that was smeared thickly with poison; his friends and companions, his family and relatives would summon a doctor to see to the arrow. And the man might say, 'I will not draw out this arrow as long as I do not know whether the man by whom I was struck was a brahmin, a k~atriya, a vaisya, or a sfidra ... as long as I do not know his name and his family ... whether he was tall, short or of medium height .. .' That man would not discover these things, but that man would die.

Why did the Buddha refuse to give categorical answers to these questions? It has been claimed by some modern scholars that the Buddha was simply not interested in metaphysical questions and that he wished to leave these matters open.15 Such an interpretation seems to miss the point. The Buddha's refusal to answe'r has a philosophically more sophisticated and subtle basis. It is stated· in the Cu!a-Miilunkya Sutta that one of the reasons why he did not explain these matters was because they were not connected with the goal and purpose of the path, namely the cessation of suffering; what the Buddha explained was just suffering, its cause, its cessation, and the way leading to its cessation.

This leaves no doubt as to the practical intent of the Buddha's teaching, but what precisely is being said about these questions when it is declared that their explanation does not conduce to the cessation of suffering? The Buddha might be suggesting that he neither knew the answers to these questions nor was he interested in pursuing the questions because he considered them irrelevant. Yet this is quite definitely not the understanding of the later Buddhist tradition, which tended to regard the Buddha as knowing everything; and the Buddha of the earlier texts certainly never straightforwardly admits to not knowing the answers to these questions. Thus if we take this line we are driven to the conclusion that either the Buddha himself or the authors of the early texts were embarrassed about his ignorance of these matters and sought to cover it up.

Alternatively the Buddha might have had answers to these questions which he simply refused to divulge on the stated grounds that it would not help his followers in their progress in the training. Such a possibility might seem to be confirmed by another tradition that reports the Buddha as once saying that there were indeed many things which he knew and understood but did not communicate on the grounds that they did not conduce to the cessation of suffering.16 But the passage ip. question gives no explicit indication that these ten questions are included in this category of things the Buddha understands but does not communicate. The third possibility would seem to be that these questions are somehow by their very nature unanswerable.

It is fairly clear that this is indeed how the early texts and the subsequent Buddhist tradition understand the matterY The reason why these questions are unanswerable concerns matters that lie at the heart of Buddhist thought. In simple terms the questions are unanswerable because they assume, as absolute, categories and concepts-the world, the soul, the self, the Tathagata-that the Buddha and the Buddhist tradition does not accept or at least criticizes or understands in particular ways.

That is, from the Buddhist perspective these questions are ill-formed and misconceived. To answer 'yes' or 'rio' to any one of them is to be drawn into accepting the validity of the question and the terms in which it is couched-rather like answering 'yes' or 'no' to a question such as, 'Are Martians green?' One's answer may be construed in ways one had not intended. Thus the Buddha tells the insistent Malunkyaputta that whichever one of these views he might embrace, the real work remains: It is not the case that one would live the spiritual life by virtue of hold~ ing the view that the world is eternal.

Nor is it the case that one would live the spiritual life by virtue of holding the view that the world is not eternal. Whether one holds the view that the world is eternal, or whether one holds the view that the world is not eternal, there is still birth, ageing, death, grief, despair, pain, and unhappiness-whose destruction here and now I declare. 18 In fact, such views (d!$tilditthi) about the ultimate nature of the world are, from the Buddhist perspective, the expression of a men~ tal grasping which is but one manifestation of that insatiable 'thirst' or 'craving' which Buddhist thought regards as the condition for the arising of suffering, and to which we will now turn. The origin of suffering: attachment, aversion, and delusion Why do beings suffer?

What is the truth or reality of the origin of suffering? At the outset it is worth drawing attention to a point of contrast with the approach to suffering found in certain traditional Jewish, Christian, and Islamic theologies. As we have already seen, and shall see more clearly , the Buddhist understanding of the world is not based upon th~ ccmcept of a creator God-omnipotent or otherwise. Thus there is no need in Buddhist thought to explain the existence of suffering in the face of God's omnipotence and boundfess love.

The existence of suffering in the world is not to be related in some way to God's purpose in creating the world and, in particular, mankind as in the traditional Christian theodicies of Augustine and Ireneus. For Buddhist thought suffering is simply a fact of existence, and in its general approach to the problem, Buddhist thought suggests that it is beings themselves who must take ultimate responsibility for their suffering. This may come as rather depressing news, but on the other hand, to anticipate our discussion of the third and fourth truths, precisely because our suffering is something that we must each bear a certain responsibility for, it is also something that we can do something about.

This way of looking at things has sometimes been perceived by people brought up in an intellectual and cultural tradition in part moulded by Christian thought as a rather bleak view of affairs, contrasting with the message of the saving Christ proclaimed by Christianity. Yet it is important to appreciate that in its own cultural context this is most definitely presented and perceived as a message of hope. Furthermore this outlook of individual responsibility does not entail that individuals are, as it were, forever and absolutely 'on their own'. On the contrary, the message is precisely that help is at hand in the form of the Buddha's teachings and of those who have followed and are following the path.

Moreover, from a Buddhist perspective, the sense that one is forever and absolutely on one's own must rest in part on a selfdelusion from which one can be eventually released by the Buddha's teachings (see Chapter 6). With the Buddha's awakening 'the doors to the deathless' are once more open for those who have the faith to set out on the path.19 As John Ross Carter has put it, there is no need of a saviour not because suffering humanity is its own saviour, but because of the efficacy of Dharma when made the integral basis of one's life.2° So suffering is created by beings, but how? The summary definition of the second truth states the condition for the arising of suffering as 'the thirst for repeated existence which, associated with delight and greed, delights in this and that'; this is then specified as 'the thirst for the· objects of sense desire, the thirst for existence and the thirst for non-existence'.

I have translated the word l!fiJii (Pali: ta!Jhii) as 'thirst'. This is its literal meaning, but in the present context it is a figurative word for strong desire or craving. In fact tr~IJii or 'thirst' belongs to the corpus of Buddhist technical vocabulary and has very specific meanings and connotations. Thus 'craving', while certainly conveying a good deal of the sense of tr~IJii in Buddhist discourse, requires a certain amount of commentary and explication. The suggestion is that deep in the minds of beings there is a greed or desire that manifests as an unquenchable thirst which is the principal condition for the arising of suffering. As the summary quotation points out, this thirst or craving takes different forms: craving for the objects of the senses, for existence and non-existence. It is the cause of suffering because it can never be finally satisfied.

This is clear with the objects of the senses: pleasure based on these is always liable to be taken from us because of their unstable and unreliable nature; on another level desire · for the objects of the senses has always the tendency to increase; never content with what it has, it is always looking for new objects to satisfy itself. But craving for the objects of the senses is just a particular manifestation of craving.

I may crave to be some particular kind of person, or I may crave fame and even immortality. On the other hand, I may bitterly and resentfully turn my back on ambition, craving to be a nobody; I may become depressed and long not to exist, wishing that I had never been born; in this state I may even take my own life; I may passionately believe that I possess an immortal soul and that I will exist after death; or I may be absolutely certain in my conviction that death will be the final end, and that I shall die and there will be no more of me. From the perspective of Buddhist thought all these feelings, desires, and beliefs are the products of the workings of tr~IJii, the workings of craving for existence and non-existence.

Yet in a world where everything is always changing, in a world of shifting and unstable conditions, craving of whatever kind will never be able to hold on to the things it craves. This is the origin of suffering. At first desires may be like the trickle of a stream, but they grow into a river of craving which carries us away like the current of a swiftly flowing river.21 Craving is understood to crystallize as 'grasping' or 'attachment' (upiidiina): the various things we like evoke desires in us; these turn to cravings; 'as a result of our craving we grasp at things and try to take possession of them; in short, we try to call them our own. Buddhist texts provide a stock list of four kinds of attachment: attachment to the objects of sense desire, attachment to views, attachment to precepts and vows, attachment to the doctrine of the self.

These suggest the complex and subtle network and web of attachment that Buddhist thought sees as enmeshing beings. The ultimately significant thing in all this is craving and attachment rather than whatever is the object of that attachment and craving. Thus it is not the objects of sense desire that cause us suffering, but our attachment to those; it is not views, precepts and vows, and the doctrine of self that in themselves cause suffering but our attachment.

This is not to say that all views, precepts and vows, and doctrines about the self are regarded as equal in Buddhist thought. Certain attachments are most definitely considered more harmful and more productive of suffering than others. Thus an attachment to the first of the five Buddhist precepts, the precept of not harming living creatures, is not to be considered as of the same order as an attachment to the habit of killing creatures. Indeed, deliberately killing living creatures is regarded as a particularly unwholesome act, and to the extent that attachment to the precept of not harming living creatures prevents us from killing, it is a positive good; nevertheless, as long as it remains an attachment-an abstract principle we tenaciously cling to-it too must remain a contributory cause of dul;kha.

The problem ·is that we can become attached to even useful and helpful things, even to the practice of the Buddha's teaching: 'It is as if there were a man who had set out on a long journey. He might see a great river in flood, the near shore fearful and dangerous, the far shore safe and free of danger, but there might be no ferry or bridge for crossing from one side to the other. And this man might think, "This is a great river in flood. The near shore is fearful and dangerous, the far shore safe and free of danger, but there is no ferry or bridge to cross from one side to the other. What if I were to gather together grass, sticks, branches and foliage and bind together a raft, and then using that raft, striving with my hands and feet, safely cross over to the further shore?" Thereupon that man might gather together grass, sticks, branches and foliage and bind together a raft, and then using that raft, striving with his hands and feet he might safely cross over to the further shore. Once he had crossed over it might occur to him, "This raft is very useful to me.

Using this raft, striving with my hands and feet I have safely crossed over to the further shore. What if I were to now lift it on to my head or raise it on my back and set off as I pleased?" What do you think of this, monks? If the man did this with the raft would he be doing what is appropriate?' 'Not at all, lord.' 'So what might this man do with the raft in order to do what is appropriate? In this case once he had crossed over it might occur to him, "This raft is very useful to me. Using this raft, striving with my hands and feet, I have safely crossed over to the further shore. What if I were now to beach this raft on the shore or sink it in the water and go on my way as I pleased?" The man who did this with the raft would be doing what is appropriate.

Even so, monks, as being like a raft, I have taught you how Dharma is for the purpose of crossing over and not for the purpose of holding on to. Those who 'understand the similarity to a raft will let go even of the teachings and practices (dhammii), let alone what are not the teachings and practices ( adhammii) '.23 This does not mean that in relinquishing his or her attachment to the precept of not harming living creatures the Buddhist saint suddenly starts harming living creatures. Rather the Buddhist saint does no harm to living creatures not out of attachment to some precept or ethical principle he or she has undertaken to live by, but because of rooting out any motivation that might move him or her to want to harm living creatures.

Thus as well as indicating the, as it were, horizontal range of craving and attachment, Buddhist thqught draws up a vertical hierarchy of attachment which the Buddhist practitioner progressively relinquishes as he or she follows the path. Something of this hierarchy of attachments is indicated by the ancient list of the ten 'fetters' or 'bonds' (saf!lyojan(l) that bind beings to suffering and the round of rebirth: the view of individuality, doubt, clinging to precepts and vows, sensual desire, aversion, desire for form, desire for the formless, pride, agitation, and ignorance. As we shall presently see, the practice of the Buddhist path begins with the taking of ethical precepts aimed at restraining particularly damaging kinds of behaviour; these provide the basis for the cultivation of meditation practices that bring the practitioner to direct experience of the subtle worlds of 'form' and 'the formless'.

Nevertheless, as the list of the ten fetters makes clear, attachment to both precepts and to the worlds of form and the formless experienced in meditation must be relinquished for the end of the path to be fully realized. The list of ten fetters includes four items that are not primafacie aspects of craving or attachment: doubt, aversion, agitation, and ignorance. The psychological relationship of aversion to craving is not hard to see. Unfulfilled craving and frustrated attachment become the conditions for aversion, anger, depression, hatred, and cruelty and violence which are in themselves quite manifestly unpleasant (dul:zkha as pain) and in turn bring further suffering. But what about doubt, agitation, and ignorance? Developed Buddhist thought understands these states as having an important psychological relationship.

Even in the absence of craving and aversion, we view the world through a mind that is often fundamentally unclear, unsettled, and confused. Not surprisingly we fail to see things as they truly are. At this point it begins to become quite apparent just how and why craving leads to suffering. There is a discrepancy between our craving and the world we live in, between our expectations and the way things are. We want the world to be other than it is. Our craving is based on a fundamental misjudgement of the situation; a judgement that assumes that when our craving gets what it wants we will be happy, that when our craving possesses the objects of its desire we will be satisfied. But such a judgement in turn assumes a world in which things are permanent, unchanging, stable, and reliable. But the world is simply not like that.

In short, in craving we fail to see how things truly are, and in failing to see !;low things truly are we crave. In other words craving goes hand in hand with a fundamental ignorance and misapprehension of the nature of the world. Thus we can state the three fundamental defilements of the mind according to Buddhist thought: greed (raga, lobha), aversion (dve.Ja/dosa), and delusion (moha, avidyii/avijjii). It is these that combine and interact, that manifest in different ways and result in du/:tkha. In this way the great focus of Buddhist thought is the workings of the mind. The processes by which the mind responds to its various stimuli to bring about either the arising of du/:tkha or the path that leads towards the cessation of du/:tkha is considered in Buddhist thought by way of a particularly important and significant teaching that I referred to in passing in recounting the story of the Buddha's awakening.

This teaching is known as 'dependent arising' or 'dependent origination' (pratitya-samutpiida/paticca-samuppiida ). Dependent arising is to be understood as in certain respects an elaboration of the truth of the origin of suffering, but this difficult teaching is intertwined with other important themes of Buddhist thought and I shall postpone its full explanation until Chapter 6. The cessation of suffering: nirval)a Ip. the normal course of events our quest for happiness leads us to attempt to satisfy our .desires-whatever they be. But in so doing we become attached to things that are unreliable, unstable, changing, and impermanent.

As long as there is attachment to things that are unstable, unreliable, changing, and impermanent there will be suffering-when they change, when they cease to be what we want them to be. Try as we might to find something in the world that is permanent and stable, which we can hold on to and thereby find lasting happiness, we must always fail. The Buddhist solution is as radical as it is simple: let go,Jet go of everything. If craving is th<:; cause of suffering, then the cessation of suffering will surely follow from 'the complete fading away and ceasing of that very craving': its abandoning, relinquishing, releasing, letting go. The cessation of craving. is, then, the goal of the Buddhist path, and equivalent to the cessation of suffer" ing, the highest happiness, nirva1,1a (Pali nibbiina).

Nirval).a is a difficult concept, but certain things about the traditional Buddhist understanding of nirval).a are quite clear. Some of the confusion surrounding the concept arises, I think, from a failure to distinguish different dimensions of the use of the term nirviil'}a in Buddhist literature. I want here to discuss n!rval).a in terms of three things: (I) nirval).a as, in some sense, a particular event (what happens at the moment of awakening), (2) nirval).a as, in some sense, the content of an experience (what the mind knows at the moment of awakening), and (3) nirval).a as, in some sense, the state or condition enjoyed by buddhas and arhats after death. Let us examine this more closely. Literally nirviil'}a means 'blowing out' or 'extinguishing', although Buddhist commentarial writings, by a play on words, like .to explain it as 'the absence of craving'.

But where English translations of Buddhist texts have 'he attains nirval).a/parinirval).a', the more characteristic Pali or Sanskrit idiom is a simple verb: 'he or she nirval).a-s' or more often 'he or she parinirv-s' (parinibbiiyati). What the Pali and Sanskrit expression primarily indicates is the event or process of the extinction of the 'fires' of greed, aversion, and delusion. At the moment the Buddha understood suffering, its arising, its cessation, and the path leading to its cessation, these fires were extinguished. This process is the same for all who reach awakening, and the early texts term it either nirval).a or parinirval).a, the complete 'blowing out' or 'extinguishing' of the 'fires' of greed, aversion, and delusion. This is not a 'thing' but an event or experience. ·

After a being has, as it were, 'nirval).a-ed', the defilements of greed, hatred, and delusion no longer arise in his or her mind, since they have been thoroughly rooted out (to switch to another metaphor also current in the tradition). Yet like the Buddha, any person who attains nirval).a does not remain thereafter forever absorbed in some transcendental state of mind. On the contrary he or she continues to live in the world; he or she continues to think, speak, and act as other people do-with the difference that all his or her thoughts, words, and deeds are completely free of the motivations of greed, aversion, and delusion, and motivated instead entirely by generosity, friendliness, and wisdom.

This condition of having extinguished the defilements can be termed 'nirvat;~.a with the remainder [of life]' (sopadhise::;anirviifJa/ sa-upiidisesa-nibbiina ): the nirvat;~.a that comes from ending the occurrence of the defilements ( klesa/kilesa) of the mind; what the Pali commentaries call for short kilesa-parinibbiina.24 And this is what the Buddha achieved on the night of his awakening. Eventually 'the remainder of life' will be exhausted and, like all beings, such a person must die. But unlike other beings, who have not experienced 'nirvat;~.a', he or she will not be reborn into some new life, the physical and mental constituents of being will not come together in some new existence, there will be no new being or person. Instead of being reborn, the person 'parinirvat;~.a-s', meaning in this context that the five aggregates of physical and mental phenomena that constitute a being cease to occur.

This is the condition of 'nirvat;~.a without remainder [of life]' (nir- upadhise~a-nirviil}alan-upiidisesa-nibbiina ): nirvat;~.a that comes from ending the occurrence of the aggregates (skandha/ khandha) of physical and mental phenomena that constitute a being; or, for short, khandha-parinibbiina. Modern Buddhist usage tends to restrict 'nirvat;~.a' to the awakening experience and reserve 'parinirvana' for the death experience.26 So far we have considered nirvata from the perspective of a particular experience which has far- reaching and quite specific effects. This is the more straightforward aspect of the Buddhist tradition's understanding of nirvana. There is, however, a further dimension to the tradition's treatment and understanding of nirvaa. What precisely does the mind experience at the moment when the fires of greed, hatred and delusion are finally extinguished? At the close of one of the works of the Pali canoh entitled Udiina there are recorded several often quoted 'inspired utterances' (udiina) said to have been made by the Buddha concerning nirvaa.

Here is the first: There is, monks, a domain where there is no earth, no water, no fire, no wind, no sphere of infinite space, no sphere of nothingness, nd sphere of infinite consciousness, no sphere of neither awareness nor non-awareness; there is not this world, there is not another world, there' is no sun or moon. I do not call this coming or going, nor standing; nor dying, nor being reborn; it is without support, without occurrence, without object. Just this is the end of suffering.

This passage refers to the four elements that constitute the physical world and also what the Buddhist tradition sees as the most subtle forms of consciousness possible, and suggests that there is a 'domain' or 'sphere' (iiyatana) of experience of which these form no part. This 'domain' or 'sphere' of experience is nirval)a. It may also be referred to as the 'unconditioned' (asmrzskrta/ asar(lkhata) or 'unconditioned realm' (asar(lskrta-/asar(lkhatadhiitu) in contrast to the shifting, unstable, conditioned realms of the round of rebirth. For certain Abhidharma traditions, at the moment of awakening, at the moment of the extinguishing of the fires of greed, hatred, and delusion, the mind knows this unconditioned realm directly.

In the technical terminology of the Abhidharma, nirval)a can be said to be the object of consciousness at the moment of awakening when it sees the four truths.28 Thus in the moment of awakening when all craving and attachments are relinquished, one experiences the profoundest and ultimate truth about the world, and that experience is not of 'a nothing' -the mere absence of greed, hatred, and delusion-but of what can be termed the 'unconditioned'. We can, then, understand nirval)a from three points of view: (I) it is the extinguishing of the defilements of greed, hatred, and delusion; (2) it is the final condition of the Buddha and arhats after death consequent upon the extinction of the defilements; (3) it is the unconditioned realm known at the moment of awakening. The critical question becomes the exact definition of the ontological status of (2) and (3). The earlier tradition tends to shy away from such definition, although, as we have seen, it is insistent on one point: one cannot say that the arhat after death exists, does not exist, both exists and does not exist, neither exists nor does not exist. The ontological status of nirval)a thus defies neat categorization and is 'undetermined' (avyiikrta/ avyiikata ).

None the less the followers of Sarvastivada Abhidharma argue that nirval)a should be regarded as 'real' (dravya), while followers of the Theravada state that it should not be said to be 'non-existence' (abhiiva). But for the Sautriintikas, even this is to say too much: one should not say more than that nirviil)a is the absence of the defilements.29 With the development of the Mahayana philosophical schools of Madhyamaka and Y ogacara we find attempts to articulate the ontology of nirviil).a in different terms-the logic of 'emptiness' (sunyatii) and non-duality (advaya). In the face of this some early Western scholarship concluded that there was no consensus in Buddhist thought on the nature of nirviil).a, or persisted in arguing either that nirviil).a was mere annihilation or that it was some form of eternal bliss.

If one examines Buddhist writings one will find material that can be interpreted in isolation to support the view that nirviil).a amounts to annihilation (the five aggregates of physical and mental phenomena that constitute a being are gone and the arhat is no longer reborn), and material to support the view that it is an eternal reality. But this is not the point; the Buddhist tradition knows this. The reason why both kinds of material are there is not because the Buddhist tradition could not make up its mind. For, as we have seen, the tradition is clear on one point: nirviil).a, as the postc mortem condition of the Buddha and arhats, cannot be characterized as non-existence, but nor can it be characterized as existence. In fact to characterize it in either of these ways is to fall foul of one of the two basic wrong views ( dr~fi/di!!hi) between which Buddhist thought tries to steer a middle course: the annihilationist view (uccheda-viida) and the eternalist view (siisvata-1 sassata-viida ).

Thus although the schools of Buddhist thought may articulate the ontology of nirviil).a in different terms, one thing is clear, and that is that they are always attempting to articulate the middle way between existence and non-existence, between annihilationism and eternalism. And it is in so far as any formulation of nirviil).a's ontolgy is judged to have failed to maintain the delicate balance necessary to walk the middle path that it is criticized. Of course, whether any of Buddhist thought's attempts at articulating the ontology of the middle way will be judged philosophically successful is another question. And again the tradition seems on occasion to acknowledge even this. Although some of the things one might say about nirviil).a will certainly be more misleading than others,. ultimately whatever one says will be misleading; the last resort must be the 'silence of the Aryas', the silence of the ones who have directly known the ultimate truth, for ultimately 'in such matters syllables, words and concepts are of no use'

What remains after all is said-and not said-is the reality of nirval).a as the goal of the Buddhist path conveyed not so much by the attempt to articulate it philosophically but by metaphor. Thus although strictly nirval).a is no place, no abode where beings can be said to exist, the metaphor of nirval).a as the destination at the end of the road remains vivid: 'the country of No-Birththe city of Nibbana, the place of the highest happiness, peaceful, lovely, happy, without suffering, without fear, without sickness, free from old age and death'.32 As if, monks, a person wandering in the forest, in the jungle, were to see an ancient path, an ancient road along which men of old had gone. And he would follow it, and as he followed it he would see an ancient city, an ancient seat of kings which men of old had inhabited, possessing parks, gardens, lotus ponds, with high walls-a delightful place ...

Just so, monks, I saw an ancient path, the ancient road along which the fully awakened ones of old had gone ... I followed it and following it I knew directly old-age and death, the arising of old-age and death, the ceasing of old-age and death and the path leading to the ceasing of old age and death So let us now turn to the path that leads to the city of nirvaiJ.a. The way leading to the cessation of suffering So far in this chapter we have seen that Buddhist thought starts from the premiss that life presents us with the problem of suffering. The schema of the four truths analyses the nature of the problem, its cause, its solution and the way to effect that solution.

The first three truths primarily concern matters of Buddhist theory; with the fourth truth we come to Buddhist practice proper. That is, the first three truths provide a framework for the application of the Buddhist solution to the problem of suffering. The second truth suggests that we must recognize that the mind has deep-rooted tendencies to crave the particular experiences it likes, and that this craving is related to a fundamental misapprehension of 'the way things are': the idea that lasting happiness is related to our ability to have, to possess and take hold of, these experiences we like. In a world where everything is constantly changing beyond our control, such an outlook brings us not the happiness we seek, but discontent.

Thus the third truth suggests that lasting happiness lies in the stopping of craving and grasping, in the rooting-out of greed, aversion, and delusion. Of course, these latter mental forces are varied and psychologically subtle; we can get caught in the trap of craving not to craveof desiring what is, in a sense, desireless, namely nirval)a. Yet as long as we crave nirva:Qa or the cessation of suffering, then by definition the object of our craving is not nirva:Qa, not the 'reality' of the cessation of suffering, but a mere idea of what we imagine nirval)a, the cessation of suffering, to be like. Nirval)a is precisely the ceasing of all craving, so even the craving for nirvaQ.a must be rooted out and eventually abandoned. The fourth truth is concerned with the practical means for bringing. this- about.

But, as I have already suggested, from the perspectiye of the path certain cravings are less harmful than others and, to an extent, even necessary, to progress along the path. Ultimately, however, as the simile of the raft indicates, attachment to even the teachings and practices of Buddhism must be relinquished. According to Buddhist thought, just as there. are various defilements of the mind-principally greed, hatred, and delusion -so there are various wholesome (kusala/kusala) qualities of the mind. As well as greed, hatred, and delusion there are then their opposites, namely non-attachment (alobha), loving kindness (adve~a/adosa, maitrJ!mettii), and wisdom (prajftiilpaftftii); Were it not for these there would be no way of breaking out of the cycle of greed, hatred, and delusion, and thus no path leading to the cessation of du/:1-kha. The principal, if not only, aim of the Buddhist path is to develop and cultivate (bhiivayati/ bhiiveti) these and related wholesome qualities.

The noble eightfold path

right view seeing the four truths { desirelessness lw isdom right intention friendliness

compassion

right speech

refraining from divisive speech

refraining from hurtful speech

refraining from idle chatter conduCt

{ refraining from harming living beings (§fla) right action refraining from taking what is not given refraining from sexual misconduct right livelihood !no t based on wrong speech and action toP"""' uruuiieo uowholewme '"'" right effort

to abandon arisen unwholesome states

to arouse unarisen wholesome states

!to develop arisen wholesome states o=t<mpl•ti= of bod> meditation

(samiidhi)

right mindfulness

contemplation of feeling

contemplation of mind

contemplation of dharma

right concentration practice of the four dhyiinas In the earliest Buddhist texts the noble truth of the path to the cessation of suffering is most frequently summed up as the 'noble eightfold path': 'perfect', 'right', or 'appropriate' (samyak/ sammii) view, intention, speech, conduct, livelihood, effort, mindfulness, and concentration.

The basic meaning of these eight items is clearly explained in a number of places in th~ early Buddhist texts , but the interpretation of the overall structure of the eightfold path is perhaps not so straightforward.34 We all have certain views, ideas, beliefs, and opinions about ourselves, others, and the world (I); depending on these we turn towards the world with various intentions and aspirations (2); depending on these we speak (3), act (4), and generally make our way in the world . So far so good, but the meaning of the last three items of the eightfold path is not so transparent. Effort (6), mindfulness ( 7 ), and concentration (8) are in effect technicalterms of Buddhist meditation practice whose expression in everyday language is less obvious. In practice they relate to one's underlying state of mind or, perhaps better, emotional state. In other words, the list of eight items suggests that there is a basic relationship between one's understanding, one's actions, and one's underlying emotional state.

The eight items of the path are not, however, to be understood simply as stages, each one being completed before moving on to the next. In fact, when we look at the extensive treatment of the eightfold path in Buddhist literature, it becomes apparent that view, intention, speech, conduct, livelihood, effort, mindfulness, and concentration are presented here as eight significant dimensions of one's behaviour-mental, spoken, and bodily-that are regarded as operating in dependence on one another and as defining a complete way (miirga/magga) of living. The eight items are significant in that they focus on the manner in which what one thinks, says, does, and feels can effect-and affectthe unfolding of the path to the cessation of suffering.

Ordinarily these eight aspects of one's way of life may, at different times, be either 'right' and 'appropriate' (samyak/sammii) or 'wrong' and 'inappropriate' (mithyii/micchii); that is, they may either be out of keeping with the nature of things, leading .one further away from the cessation of suffering, or they may be in keeping with the nature of things, bringing one closer to the cessation of suffering. By means of Buddhist practice the eight dimensions are gradually and collectively transformed and developed, until they are established as 'right', such that-they constitute the 'noble' (iiryalariya) eightfold path.

Strictly, then, the noble eightfold path represents the end of Buddhist practice; it is the way of living achieved by Buddhist saints-the stream-attainers, oncereturners, non-returners, arhats, and bodhisattvas who have worked on and gradually perfected view, intention, speech, conduct, livelihood, effort, mindfulness, and concentration. For such as these, having perfect view, intention, speech, action, livelihood, endeavour, mindfulness, and concentration is not a matter of trying to make their behaviour conform to the prescriptions of the path, but simply of how they are in all they think, say, and do.

We are talking of an inner transformation at the deepest levels of one's being. Alongside the eightfold path, Buddhist texts present'the path that ends in the cessation of suffering as a gradual and cumulative process involving a hierarchical progression of practice, beginning with generosity (dana), moving on to good conduct (sllalfila), and ending in meditation (bhiivanii); alternatively we find the sequence: good conduct (szlalslla), meditative concentration (samiidhi), and wisdom (prajiia!pafiiiii). According to this kind of scheme, the early stages of the practice of the path are . more concerned with establishing good conduct on the basis of the ethical precepts; these provide the firm foundation for the development of concentration, which in turn prepares for the perfection of understanding and wisdom.

This outlook is the basis of the important notion of 'the gradual path' which finds its earliest and most succinct expression as 'the step by step discourse' (anupurvikii kathii/anupubbi-kathii) of the Nikayas/Agamas: Then the Blessed One gave instruction step by step ... namely talk on giving, talk on good conduct, and talk on heaven; he proclaimed the danger, elimination and impurity of sense desires, and the benefit of desirelessness.

When the Blessed One knew that the mind [of his listener] was ready, open, without hindrances, inspired, and confident, then he gave the instruction in Dharma that is special to buddhas: suffering, its origin, its cessation, the path.36 The psychological understanding that underlies this is not hard to see. In order to see the four truths, the mind must be clear and still; in order to be still, the mind must be content; in order to be content, the mind must be free from remorse and guilt; in order to be free from guilt, one needs a clear conscience; the bases of a clear conscience are generosity and good conduct.

The eight items of the eightfold path can also be analysed in terms of the three categories of good conduct, concentration, and wisdom: the first two items of the path (view and intention) are encompassed by the third category, wisdom; the next three (speech, action, and livelihood) by the first category, good conduct; and the final three (effort, mindfulness, and concentration) by the second category, meditative concentration.37 That the sequence of the items of the path does not conform to the order of these three categories of practice highlights an understanding of the spiritual life that sees all three aspects of practice. as, although progressive, none the less interdependent and relevant to each and every stage of Buddhist practice. The practice of the path is not simply linear; in one's progress along the path it is not that one first exclusively practises good conduct and then, when one has perfected that, moves on to meditative concentration and finally wisdom.

Rather the three aspects of the practice of the path exist, operate, and are developed in a mutually dependent and reciprocal relationship. In other words, without some nascent sense of suffering and what conduces to its cessation one would not and could not even begin the practice of the path,_ This is not necessarily a conscious understanding capable of being articulated in terms of Buddhist doctrine, but is perhaps just a sense of generosity and good conduct as in some way constituting 'good' or wholesome (kusala/kusala) behaviourbehaviour that is in accordance with Dharma and conduces to the cessation of suffering for both oneself and others. The details of the cultivation of the path to the cessation of suffering form the subject matter of Chapter 7, but let us now turn to consider Buddhist practice more generally: the way of life of Buddhist monks, nuns, and lay followers: