Paticca Samuppada

Introduction

Paticca samuppada - dependent origination - is an indispensible teaching, a thorough understanding of which is necessary for the penetration of the Buddha's doctrine. Together with anatta [ § ] it is one of the hallmarks of Buddhism, distinguishing it as a unique religion. The Abhidhamma Pitaka (third section of scripture § ) primarily focusses on these two teachings. Where the teaching on anatta proceeds by 'seperating' phenomena into basic constituent parts (thus revealing their impersonality) the doctrine of dependent origination proceeds by 'incorporating' phenomena, showing that they are all conditionally related. In either case the direction is the same - liberation.

- Just as the great ocean has but one taste, the taste of salt, so also this Dhamma and Discipline has but one taste, the taste of liberation." Udana 5

One way of considering the teaching of paticca samuppada is as a general statement of universal law.

- "When there is this, that comes to be;

- With the arising of this, that arises.

- When this is absent, that does not come to be;

- With the cessation of this, that ceases." Majjhima 79

This simple formula applies to all things: trees (arising due to rain, nutriment, etc.), this web page (due to my computer, electricity, etc.), planetary systems (arising due to...). It outlines a conditioned genesis which can sometimes be mis-understood as implying a 'first cause,' as implying some kind of original 'this' (God?). We then need then to ask: "what was the 'this' that caused the arising of that first 'this' - and the cause of that... ad infinitum. Which of the balls in the animation above caused the knock-on? The intention with paticca samuppada [P.S.] is neither to propose or deny primordial origin - or final extinction for that matter - but to examine causal, conditional relationships - between this and that, birth and death, ignorance and suffering, etc. The buddha didn't invent this teaching, it is just an expression of natural law. The more we study our world through this principle what we increasingly see is a web of causal connectedness, inter-relations and non-independence. Seeing this, compassion quite naturally arises; abusing you is only harming myself. This is not saying "we are all one being" but just that we are not wholly seperate. Take care of me

A second approach takes the same principle but applies it directly to the human condition and most specifically to the problem of suffering. Dukkha is a condition that has arisen. If we examine its causes we can initiate its cessation - and this is truely the point of the Buddha's teaching. We will mainly look at the linked series in the forward direction but there are many scriptural instances where it is presented in reverse: "with the cessation of craving there is cessation of feeling." [see: phassa § ]

Are you ready?

The traditional presentation is a list of twelve terms - each one linked causally to the next. The formula repeats along the following lines: Avijja-paccaya sankhara: "Through ignorance are conditioned the sankharas... sankhara > viññana... etc."

Paccaya = 'condition', and is something on which something else, the so-called 'conditioned thing', is dependent, and without which the latter cannot be.

The image of paticca samuppada [P.S.] is sometimes a chain, or the rim of a wheel (see below). It is a complex subject with varied opinions as to its meaning and I encourage you to read widely if you want to get a good understanding of it - at least to collect a range of data to form your own opinion :). For easy reference the navigation bar includes both the Pali and English for all twelve links. What isn't apparent is the extent of the last link. It is in fact jara-marana (old-age and death) but even this is abridged from: "old-age, death, sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief and despair - such is the origination of this entire mass of suffering" - that is: dukkha. With ignorance as cause - suffering is the result. To give some idea of how the Buddha regarded P.S. here are a couple of quotes.

- "Profound, Ananda, is this Dependent Arising, and it appears profound. It is through not understanding, not penetrating this law that the world resembles a tangled skein of thread, a woven nest of birds, a thicket of bamboos and reeds, and that man does not escape from (birth in) the lower realms of existence, from the states of woe and perdition, and suffers from the round of rebirth." Digha 15

- "He who sees dependent arising sees the Dhamma; he who sees the Dhamma sees dependent arising." Majjhima 28

The Four Noble Truths is the essence of the Buddha's teaching so it is not surprising to find the inter-dependent principle of P.S. included in its outline. Looking at the four truths in relation to the general formula above we see that:

- And that...

The emphasis is clearly on the causal relationship between craving and suffering. If you look at the nav. bar links you will see that the pivot point of feeling and craving has been marked. Of all the link points this is one of the most crucial - a 'weak' link. We can't avoid contact (with the world) nor the resultant feeling but, we do have the possibility of avoiding, or at least tempering craving. Grasping is another 'break point' as, having grabbed something, we can let it go. The importance of this is made very clear in the "grasping of the five khandhas" as the summary definition of dukkha [see: 1st Noble Truth § ]. There is another potent but quite subtle break point called manasikara (attention) between viññana and nama-rupa [see: nama-rupa]. Directing the mind with this clear-wise attention to any of the 12 links will bring a greater understanding of that factor, and the role it plays in your inner world. More clarity around one will help bring the others into a more manageable perspective.

There are two principle approaches to P.S. - "three life" and "momentary". A wide range of authoritative views support both and a clear conclusion is difficult. The 3-life model begins with the past life, going on to this present life and then to a future life. The following table outlines the relationship between the three successive lives.

| PAST | Karma-Process (kammabhava) 5 causes: 1,2,8,9,10 | |

| PRESENT | Rebirth-Process (upapattibhava) 5 results: 3-7 | |

| Karma-Process (kammabhava) 5 causes: 1,2,8,9,10 | ||

| FUTURE | Rebirth-Process (upapattibhava) 5 results: 3-7 |

- A one-page presentation of P.S. (supporting the "three life" theory).

- Another - arguing against the "one-life" model.

- A detailed, well-reasoned and documented support for this-life

- Part of a well balanced book by a renowned Thai scholar - generally supporting 'this-life.'

It is not my intention, nor even within my scholastic ability, to refute the 3-life theory, however, in terms of reflecting on and applying this teaching in daily life, the second approach - "momentary arising" - seems to me more workable or applicable. Another term for this approach is "psychological unfolding." The time-frame is the matter generally in dispute and consideration here can be given to the timeless nature of the Buddha's teaching and the thought that P.S. is not even an 'unfolding' as this implies a (time bound) process. One author suggests that P.S. is entirely structure - not process. The following pages are a range of musings with the 'this-life model' in mind. Every attempt is made to reflect the Buddha's teaching as accurately as possible but do question this accuracy - as you should with any dhamma presentation [see: Kalama Sutta § ].

The 'momentary arising' model suggests that any moment or 'slice of experience' of one's life - this life - that has ignorance as its starting point tends to have suffering as its end result. Imagine being at the top of a tree. One is ignorant (distracted, deluded, heedless, or some such) and as a result looses ones grip and falls. On the way down there are various branches (consciousness, contact, feeling, etc.) but they can be a bit of a blur. What you do know tho' is the THUD when you hit the ground - the end - ouch - dukkha! The passing of the various factors is usually rapid but there is some space - we are not total victims. If the aim of Buddhism is the ending of dukkha (nibbana), and this can happen in this present life, then it is not necessary to die to break this chain. It is not a deterministic formula, it is a teaching leading to liberation. With wisdom, one can have the clarity to grab one of those branches! Or just not fall in the first place.

Another way of considering P.S. is using an intermediary time span - neither over three life times nor in-an-instant - but over days, or weeks or years. An action now generates (plants the seeds for) future consciousness, feeling, etc. - "at some later time." It is also useful to consider P.S. as non-linear [see: mindfulness § ]. The result of actions depends on the actions - and many associative conditions. We can consider the twelve links as essential marker points on our 'map' but not as the whole map itself. The Buddha was pointing to suffering in this life - the causes in this life - and the end, in this life. His teaching presents itself as not being particularly cosmological, metaphysical or philosophical but essentially topical, practical.

Whichever approach seems most relevant to you (and they need not be mutually exclusive) it still remains to study each element of the twelve links to develop a clear understanding of these key terms and the overall mechanism of P.S. Equally important is to study the workings of your own life in relation to the causal, inter-related principle. Can you see patterns of activity, habitual associations, linked sequences of mental-emotional processes that govern, even dictate, your life? When: they say that... you... or, when: you see that .... you... and so forth. One question is relevant here - that of free will. With every-thing in the world determined by causal conditions, is this not some sort of fatalism? No, no. But, where is the break point? What is the cause, the supporting condition for intention, volition, the point of free choice? Read the page on nama-rupa, likewise tanha & upadana.

There are other formulations of the P.S. principle.

In the Upanisa Sutta the following series of links are presented:

- Faith > Joy > Rapture > Tranquillity > Happiness > Concentration > Knowledge-vision > Disenchantment > Dispassion > Emancipation > Destruction of the asava (ie. nibbana).

The principle of 'paccaya' - conditionality - is the same for all these lists. Ie.: "with faith as condition - arises joy > with joy as condition arises...".

There is a similar list but instead of 'faith' it begins with:

- Skilful moral conduct > absence of remorse > Joy > Rapture > Tranquillity > Happiness > etc.

Another sutta (Digha II.58) offers a series reflecting more on 'social' suffering:

- Feeling > Craving > Seeking > Gain > Valuation > Fondness > Possessiveness > Ownership > Avarice > Gaurding > Suffering = taking up the stick, the knife, contention, dispute, arguments, abuse, slander and lying. This is 2500 years ago. How much has changed?

There are also instances where the link-set is presented in both forward and reverse directions. Eg. starting with suffering: "What is the support condition for suffering? Birth. For birth? Becoming?.... ending with Ignorance."

The law of kamma (action § ) features prominently in the working of P.S.. In relation to the 3-life model you can see in the table above that our past-life was a kamma-process. In the present, items 8-10 are also kamma-processes. In the moment-by-moment model our actions can both increase or, more importantly, moderate our ignorance. The list above has: Faith + Joy leading to knowledge and likewise, initiating skilful moral conduct leads to happiness, knowledge etc. Our choices (actions - kamma) directly affect consciousness.

As well as the image of a chain P.S. is sometimes presented as a wheel, notably in the Visuddhimagga (Path of Purification) and in other commentarial literature. Do allow, considering the complexity of P.S., that this representation is a little superficial. Here is an example - which also includes information on the six realms of existence [ § ]. The wheel is a primary Buddhist symbol [ § ] but in the case of P.S. we can think of the wheel of samsara - the continuing process of ever again and again being born, growing old, suffering and dying. Buddhism looks to break the cycle.

Avijja - ignorance

Avijja is the first link in the chain but should not in any way be thought of as the starting point, the 'causeless root-cause of the world.' The images of the circular chain and the wheel representing paticca samupada [P.S.] are useful as neither has a defined starting point. The conventional layout of the P.S. formula is intended for reflection, not as any kind of finite cosmological or psychological definition.

- "No first-ignorance can be perceived, monks, before which ignorance was not, and after which it came to be. But it can be perceived that ignorance has its specific conditions." Anguttara X.61

So what are the 'specific conditions' that cause ignorance?

And then we want to ask after the cause of the taints. Read the section on asava [ § ] but enough here to note that the standard list of four includes ignorance. Have we just gone in a circle here? Trying to position avijja creates a loop similar to the one we find in the eight-fold path: the first step is right view (of the Four Noble Truths) and the last of the Four Truths... is the eight-fold path. We will find many such loops in P.S. as we proceed. Nibbana (the end goal) can be defined as: "being perfect in knowledge (vijja)" and, "endowed with higher knowledge (te-vijja)." If nibbana is where we finish then we are clearly starting from "the absence of vijja," which is: a-vijja. So, avijja sits first on the list as representing a primary obstacle to liberation - and a primary cause of dukkha. The teaching of the Buddha has at its core the Four Noble Truths and, as a working summary, ignorance is not knowing the Four Noble Truths.

avijja = ignorance; unawareness; unknowing; obscured awareness; delusion about the nature of the mind. All unwholesome states of mind are inseparably bound up with it. The standard English translation, ignorance, has its roots in the Greek word 'gnosis' = (revealed) spiritual knowledge, and it is where the words diagnosis and prognosis come from. Ignorance is the state of not-knowing or, in the particular context of dhamma, non-wisdom. We tend to think of knowledge in terms of facts and information but the path to freedom (from the wheel of birth and death - the chains of P.S.) lies in the space of the mind, the non-positional 'knowing' that is the domain of awareness. And what does this awareness know? - the Four Noble Truths.

Underlying the Four Noble Truths is the teaching on not-self (anatta § ) and an even more basic definition of avijja is the held belief that: I am the five khandhas. I believe that the five khandhas are me, that they are mine and that they constitute my-self. This parallels the the Buddha's summary definition of suffering as "the grasping of the five khandhas" [ § ]. We can also consider:

- ignorance of the 3 conditions [ § ]; the basic truth for all existance: that everything is impermanent, is dukkha (unsatisfactory) and is not-self.

- ignorance as confused thinking based on conjecture and imagination, conditioned by beliefs, fear, and accumulated character traits. This is the kind of mental 'squirrel in a cage' that most people experience. Not dukkha with a capital 'D' but just the everyday form of ignorance/confusion. Yes?

The overall thrust of the Buddha's teaching is "freedom from suffering" and where the Four Noble Truths presents the conditioned relationship of desire and dukkha we see P.S. offering avijja-dukkha. The purpose is the same: to understand the cause of dukkha is to have a key to be free from dukkha.

When the mind operates based entirely on avijja, it experiences all things as being independent, seperated, alien entities. The observation is one of me (here) holding various knowledges, views, etc. about all-that-stuff (out there). Even the body is seen as a kind of other-thing; it is my body - my thoughts, my children, my car and so forth. The apparent, or presumed point of observation is thought to be the centre, with all else peripheral - this is what it is to be ego-centric. Most of us suffer from this delusion but in the normal run of things are not so extremely positioned. I doubt you would be reading this if you were. There is hope :)

From this ego-centric position another ignorance that we fall prey to is that of continuity. This appears in two ways. The first is a presumed extension of existance. Of course we all know that everything is impermanent but our knowledge is largely of the factual, conceptual variety. I do know that I am going to die - but of course it is... when? certainly later - always at some other (later) time. I don't truely know the nature of impermance. It is often not until there is a close death or we get the terminal diagnosis that we really begin to investigate impermanence. The second, and related aspect of continuity is the creation of time - the past and... OF COURSE, the future - my future. It is the only way the first bit can work. If I had a past, and I am now, then I will most likely have a future. It is this ongoing (ignorant) attempt to sustain, this attempt to substantiate 'me' that is the conditioning factor for the next link - sankhara.

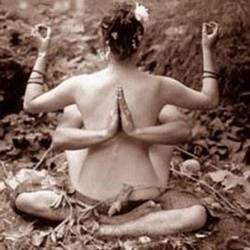

In terms of dealing with ignorance - in the context of liberation - we can use a very broad definition of avijja: not being familiar with your own mind. It is through this non-familiarity that we confuse our conditioned perceptions of the world, of reality, with the truth - the dhamma. We tend to regard the impermanent as permanent, the unpleasant (dukkha) as pleasant and the not-self as self. Part of the problem here is that there is much business in our lives and there is not a lot of stillness, not a lot of time to reflect on the nature of... well, nature. Too much of our effort to be free of suffering is focussed on attacking the shadow of suffering - we fail to see its actual form. Meditation is an effective technique - stop, look and listen.

So, a mind that is centered and still, gives rise to knowledge, wisdom. The cultivation of this knowledge is the path. All the things of this world that come parading before the senses for you to know are potential causes of suffering. Gaurd the mind against latching onto the preoccupations that appear in relation to those things. Let them be, let them just exist in line with their nature. Put your mind at ease. Don't fasten onto the formations of the mind or suppose these things to be this or that. As long as you suppose your-self, you're suffering, your awareness is obscured; there is avijja. When you can truly know this, penetrate this, the transcendent will arise within you -- the noblest good, the most exalted happiness a human being can know. These words of encouragement from Ajaan Lee Dhammadharo.

- "Monks, I don't envision even one other obstruction -- obstructed by which people go wandering & transmigrating on for a long, long time -- like the obstruction of ignorance. Obstructed with the obstruction of ignorance, people go wandering & transmigrating on for a long, long time." Itivuttaka I.14

- avijja is synonomous with moha (delusion) the third of the three poisons

- it is one of the asava (taints, effluents, corruptions, out-flows)

- one of the anusaya (proclivities, inclinations, tendencies)

- one of the samyojana (fetters)

and.... needless to say it regularly figures as a prominent 'bad guy' in many other aspects of the teachings.

Sankhara - formations

From ignorance as a requisite condition come sankharas - the second link in the chain. It is one of the most difficult terms in Buddhist terminology and has several different shades of meaning depending on its context. A single word translation presents problems. We will focus on the specific context of paticca samuppada [P.S.] but, as it is a key term in Buddhist doctrine and the implications of sankhara in P.S are not independant of the wider doctrine, we will also explore the full range of meaning.

Before we get too involved in that perhaps a broad outline and translation of the term may be useful. Through its general use in the Pali canon sankhara can be thought of as 'formation' or, 'determination' or 'fabrication.' The difficulty is that the term can refer either to 'the act of forming' or to the passive state of 'having been formed' or to both. Sankhara has its roots in classical Sanskrit with the early meaning of: "preparation" and "sacrament," also in philosophical literature: "former impression, disposition." The prefix san means "together" and the root kar means "to make" so the implication is of an aggregate, a combination, or an assemblage - things put together. I will generally use 'formation.'

In the context of P.S. sankhara takes on the active aspect of 'forming' and in this respect is synonomous with kamma. It is a conscious and active kammic determination. It covers both wholesome and unwholesome volitional activity and in this specific sense sankhara could be translated as "kamma-formation." In relation to the three life model this includes actions of body, speech or mind (in the past). As part of a (this-life) evolving sequence - ending in dukkha - sankhara is more the dynamic process of mental formation (fabrication, assembling) which arises through the misconceptions of avijja. These formations can be considered as rudimentary thought forms, little bubbles. Many of them survive and take on (or we 'give' them) associative labels, names, values - there is the arising of perception - they assume an identity [see: nama-rupa]. As sankhara (forming) these 'bubbles' take on the potential of being 'formed.' The things of the world are just as they are, they have no names, no value. When we are born we have no name, no value. Through avijja arises sankhara and when these sankharic 'bubbles' are given heed - there is this kamma-forming - the little bubbles don't just go 'pop,' they persist and this persistance conditions the arising of viññana (consciousness). The image on the 'wheel of life' [ § ] is that of a potter making pots for future use. The implication here is that some choice is available around this forming. For most of us, the "falling out of the tree" image presented in the introduction, is what we usually experience: avijja... thud ...dukkha. Nevertheless studying and reflecting on these traditional frames - especially in the context of meditation - establishes a knowledge, a familiarity with your own mind that expands the possibilty of choice.

Here are a few other uses of sankhara:

- It is the fourth of the five khandhas [ § ] and here includes all 'mental formations' whether they belong to 'karmically forming' consciousness or not. In the Abhidhamma, fifty mental formations are distinguished, seven of which are constant factors of mind. As one of the khandhas sankhara is sub-divided into three: volition (cetana), contact or sense impression (phassa), and attention (manasikara). Volition is the principal 'formative' factor here.

- The suggested translation above for sankhara as 'kamma-formation' - actions of body, speech and mind are sometimes found used in quite a different sense with body-sankhara referring to the function of in-and-out-breathing; the verbal function of thought-conception and discursive thinking; the mental-function of feeling and perception.

- The more usual use of sankhara has the active mode of 'forming' but it also has the sense of anything formed and conditioned (or determined or fabricated). In this context it includes all things in the world, all phenomena of existence - trees, houses, oceans, people, etc.

- Sankhara sometimes means 'volitional effort.'

Sankhara has this curious twist as it is not merely a combination of several factors. It is a changing combination of changing factors, since the combination itself is changing. In the broadest sense the term covers all things, physical or mental, fashioned by causes or conditions, as well as the forces fashioning them and the processes by which they are fashioned. Jumping a few links in P.S. - but within the general bounds of the term - we can consider that sankhara refers not only to matter and properties of matter known as "corporeality" (rupa), but also to mind and properties of mind known as "mentality" (nama).

There is a well known passage in Pali that highlights the conditioned or compounded nature of sankhara:

It makes clear that all sankhara (formations) are impermanent (anicca) and subject to suffering (dukkha) but it is necessary to introduce the word 'dhamma' to qualify the third condition of existance, 'anatta,' as dhamma is more complete and all-embracing as regards existance as it includes the unconditioned (the unformed = asankhata; the not-sankhara), ie. nibbana. It would be wrong to say that all dhammas are impermanent and subject to change, for the nibbana-dhamma is permanent and free from change. For the same reason, it is correct to say that not only all the sankharas (ie. sankhata-dhamma), but also that all the dhammas (including the asankhata-dhamma) are anatta; not-self, lacking an ego or essential person-ality.

Sankhara can be conditioned by ignorance (as in the case of P.S.) or not. They can be volitional or not (as in the case of khandhas). They can be 'static' or formed. See that nothing is a unity and nothing is an entity - all arises due to conditions. Sankhara arises in the mind and is a persistant factor in the on-going conditioning (paccaya) of the mind.

Viññana - consciousness

Viññana (consciousness) is the third link - conditioned by sankhara (formations). First - pronounciation: The n-tilde is a 'Spanish n' and viññana is sometimes written phonetically as 'vinyana' where the 'ny' is the same as in canyon.

In the 3-life model of paticca samuppada [P.S.] this consciousness is commonly called "re-linking consciousness" (patisandhi-viññana) or "kamma-resultant consciousness" (vipaka-viññana) [see table § ]. From ignorant actions in our past life (avijja & sankhara) it is viññana that flows on into, and arises in this new life. The idea being that viññana - in union with sperm and egg - is the definitive factor for the arising of a new life. This is conception in the full and complete sense. It seems reasonable that the process of conception and birth is clearly more than just a mechanical sperm-egg thing and, by extension, it also seems reasonable to presume rebirth. Kamma/viññana seems a reasonable medium for this but, did the Buddha intend the P.S. structure as the explanation of this? The underlying principles of condition-dependant arising can be seen within the death/rebirth process but in this context of P.S. we will consider the arising of viññana as part of the flow of this-life, of experience, in this life.

It may be helpful to explore a broader definition of viññana before finding it a position in P.S.

- "When there is the sense-object, the sense-organ (in working order) and contact between the two, this three-fold union (object, organ, contact) is the arising of consciousness. If the arising is dependant on eye and form we talk of visual-consciousness (nose + odour = nasal c.; etc.)." (part Majjhima 28)

There are then six forms of consciousness - each arising dependant on one of the senses (the mind as the sixth). This a stock definition of viññana and although in P.S. the senses are not yet 'in play' this definition reinforces the dependant nature of viññana. It can not arise, nor exist independently.

- "without supporting conditions, there is no arising of consciousness" (Majjhima 38)

One factor always present with viññana is intention - we have to intend to make contact with (eg. to look at) something before viññana can arise. In the frame of P.S. this intention is sankhara but the consciousness that arises here is still quite nascent, it is 'simple.' A term in Pali worth consideration is bhavanga-citta. Bhava = becoming; anga = factor; citta=mind. It is a kind of sub-consciousness that, as yet, has no (formed) subject, has no (formed) identity, no (formed) "I" within it. I repeat the word 'formed' as this consciousness does have the seeds of formation - this is sankara, the forming agent. Because ignorance was the primary conditioning factor it is inevitable that consciousness takes on, or forms, ego-identity. The "falling out of the tree" image in the introduction is clear: you will likely hit the ground.

It is this link - the arising of conditioned consciousness - that is indeed the point of birth. Not as a fetus, but birth as a seperate ego-self, a 'me' - an 'I' - a not-you. We can talk here of self-consciousness. A simple example: someone points a camera at you and you become self-concious. You may have been day-dreaming but now there is viññana - and this consciousness (your thoughts) turn to, in fact create, nama-rupa. Is your hair (rupa) tidy? You are annoyed (nama) at the intrusion, etc. There is (minor?) suffering as a result.

Consciousness can be free of the self bit - in fact this is the whole point of the teaching - but...

We will look more closely at nama-rupa on the next page but briefly it translates as name and form or, mind and matter. Again, this is not the body-mind development of a fetus but it is the arising in (or arising with) consciousness, of body-mind awareness. You are sitting here reading and someone calls out to you: "Hey, you've got a bogey on your nose." The nose was there all the time but suddenly it arises large in consciousness (as rupa) along with the embarassment, anger, etc. (as nama) - nama-rupa is "born."

When ignorance is not present - that is when we clearly see the truth of the way things are (we understand the Four Noble Truths) - form is just form, bogey is just bogey, there is no problem, there is no suffering. With ignorance as cause viññana arises, and it is born as my conciousness - it is mine, it is me, it is: self-conciousness. There is a fixed relationship between viññana and nama-rupa - whether avijja is present or not. "It is as if two sheaves of reeds were to stand leaning against one another. In the same way, from name-&-form as a requisite condition comes consciousness, from consciousness as a requisite condition comes name-&-form. If one were to pull away one of those sheaves of reeds, the other would fall; or, if one were to pull away the other, the first one would fall." Samyutta XII.67

Another way of considering the time relationship of sankhara and viññana, positioned somewhere between sankhara in a past-life and sankhara as part of a moment of this-life, is to think of your intentions (sankhara, in this-life) but say a few weeks ago. Those intentions, that kamma, perhaps took you to a new town and this gave rise to quite specific consciousness which could not have arisen in the old town. Past action results in present birth.

The theories can roll on endlessly but, for me, the main criteria in study is: What can be done with this? How can this particular teaching be put to use in my life? It is possible to observe the subtle movements of the mind, although perhaps not every branch of "that tree" will be visible as we fall. Study is like gathering clues, collecting maps. The suggestion is that there is this intention > consciousness movement that takes place, and that it leads to suffering (when founded in avijja). Can we see it? Must we always be a victim of our (ignorant, habitual) impulses? Nah ! Break the chains of bondage - take charge of this mind. There is no spoon :)

Viññana is one of the five khandhas - see further discussion there [ § ].

It is also one of the 4 nutriments (ahara):

- material food

- (sensorial and mental) impression (phassa)

- mental volition (mano-sancetana)

- consciousness (viññana)

The details of this list are interesting in terms of what feeds life but enough here to note that it represents four links from P.S. - nama, phassa, sankhara, viññana. You will find many terms repeating, in different contexts and in a variety of (dependant) combinations, as you persue your studies. These lists all have dukkha (the release from) as their underlying target and together they build a network of definitions, a complex system of feed-back loops. Each list - P.S. included - has its specific implications and each enriches the other. Don't get caught expecting to find 'the list' - the singular, definitive solution to the tangled web that is dukkha.

Nama-rupa - name-form

Dependant on viññana arises nama-rupa.

We earlier looked at the mutual dependancy of viññana, and nama-rupa and saw that one can not exist without the other. Additional to the example of the mutually supportive "two sheaves of reeds" we can consider another simile: A blind man with stout legs, carrying on his shoulders a lame cripple with keen eye-sight. Only by mutual assistance can they move about.

- Nama is literally 'name.' The principle or distinguishing mark (of an individual), the label (by which one is known). In personal use it refers to the non-material attributes; what we might think of as mentality, personality.

- Rupa is: form, figure or appearance. It is contrasted with what is unseen (primarily nama) so is often translated as matter. In a personal context it refers to our physicality, our body.

- In the context of P.S. the two terms are inseperable and together are translated as: name-form, mentality-corporeality or mind-body.

We have already looked at various 'loops' within paticca samuppada [P.S.] and nama-rupa contains several such loops, or perhaps inter-woven 'layers.' Our first condideration in this respect is the five khandhas [ § ] - the primary Buddhist definition of being human: rupa, vedana, perception (sañña), sankhara and viññana. Four of the five are part of P.S. which makes sense if you see that P.S. is also about 'coming into being' - or birth - as a human. Khandha and nama-rupa are considered synonymous with nama being equal to the four mental states. The main difference is that the khandhas are presented as the objects of grasping (upadana) where P.S. is the process of grasping. The distinction - in the context of P.S. - is that nama-rupa is still being formed, with sankhara as the formative agent. Khandha is free of avijja.

Nama-rupa is the pivotal point where we begin to evolve "a seperate sense of being" beyond the simple, nascent consciousness that is viññana. We now have the beginnings of a duality - body and mind - where the mind (grounded in avijja) begins to cognise reflectively on its 'environment.' In the "falling out of the tree" example: Initially there was just falling. Now we have an evolving sense of 'me' falling - and the tree. The 'me' has now become a subject (nama) which is aware of an object (rupa). This object awareness is still vague, a bit of a blur, and what is needed for the subject-object relationship to come into focus is ayatana - the six sense bases. Because the whole process is rooted in avijja, nama is driven to this further self-becoming. The compulsion for relationship (subject-object) is irresistable. So, dependant on nama-rupa arises ayatana. This duality is deepened at phassa.

It can be seen how nama-rupa contains the whole chain and is in effect a 'hinge point' for the whole structure. Rupa is both the body itself (including the senses) and the sense objects. With either of these absent there can be no contact. Nama is feeling, perception, sankhara (contact, attention, and intention) and viññana - in effect, the five khandhas. It is viññana that provides the catalyst for physical birth, the coalescing of the khandhas, without which foetal conception would fail. In terms of momentary mental birth, without nama, especially viññana, there would be nothing to activate experience of the khandhas - no feelings, perceptions, etc. - as there is no intermediary between rupa (as body, with sense bases) and the sense objects. There might be contact but zero resultant cognition. Duh!

We see nama-rupa presented as a synonym for the five khandhas and so see sañña introduced for the first time. The development of perception is the formation of a value system, a structure of ideas, which usually includes memory. [see: emotion, in vedana] What we have, at this point in the flow of P.S., is my existance beginning to take on "meaning," to have some relative value. The evolved form of viññana we now have means we can move on from basic conscious awareness to cognition. We have the seeds of an ability to reason, to consider. This is certainly part of the dualistic "seperate sense of being" we looked at earlier but it includes the beginning of a question - the question - who am I? Perhaps a bit like waking up in the morning. With the earlier viññana we were awake but it was mostly "scratch and grunt." Now we wake up and go: "huh? - what's happening?" There is a clear sense of me - and me falling out of the tree - along with: "I am not sure this is a good idea!" In relation to the examples on the previous page we see that there is now a strong sense of 'me' - and my hair - and the relative value or idea of untidiness. Or, there is 'my' nose - my bogey - and my shame - and, in both examples - my dukkha.

We also saw sankhara, included as part of nama, sub-divided into three: contact (phassa), attention (manasikara) and intention (cetana). The second two factors provide the (potential) spring-board for liberation. We will look more closely at the idea of a 'break point' in vedana-tanha but it is at this point in P.S. that we set the scene for that break. There has clearly been earlier contact but it is not until now that we have a cognitive perspective on that contact. Manasikara can be translated as: pondering, thought, attention, reflection. It is the mind's first 'confrontation' with an object (as an object) and it correlates the various associated mental factors. So, someone yells an insult. There is contact and manasikara is what confronts - like a bouncer at a club entrance - the object (or process). There is some reflection, invesitgation and evaluation and from this there is some basic intention - what to do with the 'applicant.' Bouncers are more renowned for their muscle so the level of intelligence and discrimination we have here is not terribly complex. The 'mano' of manasikara goes on to form the sixth sense-base of ayatana.

Manasikara is commonly encountered as yoniso-manasikara: wise (or reasoned, methodical) attention or, wise reflection.

- "When a monk attends (manasikara) inappropriately, unarisen effluents arise, and arisen effluents increase. When a monk attends appropriately (yoniso-manasikara), unarisen effluents do not arise, and arisen effluents are abandoned." Majjhima 2

It is the combination of sañña (with its memory component) and yoniso-manasikara that provides us with the possibility of escape from the seemingly endless cycles of P.S. We have an ongoing variety of 'confrontations' in, or with the world and some we let into the 'club' (that is our life) and some we don't. We register the results - and we learn. Nama-rupa is not so much a point where we change course but where there is contact, where there is (wise) attention, and this is followed by an intention (to change course).

Ayatana - senses & Phassa - contact

The two links of Ayatana and Phassa have been combined here because they share the same, if not even stronger, interdependant relationship that nama-rupa does. Also ayatana is implicit in nama-rupa and in the Mahanidana sutta (Digha ii,2) we find the links of dependant arising go from namarupa directly to phassa with no mention of ayatana.

The term 'ayatana' has a broad range of meanings...

- extent, region; sphere, locus, place; position, occasion

- exertion, doing, working, practice

- sphere of perception or sense in general, object of thought, sense-organ

It is this last definition that mainly interests us in relation to paticca samuppada [P.S.] and the nav bar heading should be sal-ayatana where 'sal' is Pali for six. "There are these six bases: the eye-base, the ear-base, the nose-base, the tongue-base, the body-base, the mind-base. With the arising of nama-rupa there is the arising of the sixfold base. With the cessation of nama-rupa there is the cessation of the sixfold base." Majjhima 9

There are actually 12 'spheres' or 'bases' on which the mental process depends: the five physical sense-organs plus the mind-base (the six personal bases) and the six objects (the so-called external bases; sight-object etc.). It is important to note that the external bases are not the physical, bodily things but what impinges on or is 'offered to' the personal bases; eg. in the case of the eye: colors, differences of light, etc. The last personal base, mind-base = manayatana and is a collective term for all consciousness. Mano + ayatana. This gets a bit tricky and you could explore the difference between viññana (consciousness) and mano (mentality) and citta (heart-mind) [ § ]. Mano primarily deals with the intellectual functioning of consciousness so manayatana is in effect 'the boss' of the other five more simple senses although its "intellectual capacity" is limited with there being 'higher,' more evolved forms of mano.

Our previous, broad definition of viññana had:

"When there is the sense-object, the sense-organ (in working order) and contact between the two, this three-fold union (object, organ, contact) is the arising of consciousness."

The critical distinction here is that our earlier discussion of viññana focussed on the bhavanga-citta, a kind of sub-consciousness that, at that point in the chain, has no (formed) subject, has no (formed) identity, no (formed) "I" within it. It is the seed of nama-rupa which in turn primes the senses, sets them up ready for contact.

So, building on our example in nama-rupa. Someone insults you, aspects of body-mind are stimulated (awakened, 'born') and this activates ayatana of which manayatana is general overseer. The information so far offered to you (the insults; tone of voice, body language, etc) we can think of as the collective external bases - in effect this is nama-rupa which manayatana receives and evolves. Bear in mind that both nama and rupa are limited and contextual; we are dealing with specific characteristics of phenomenon - their behaviour and appearance - essentially offered to us through the distorting lens of avijja. So, we believe (think, imagine, perceive, feel, etc) the person insulting us said: "Blah boop pinch the macked gringle badly you did." Even if they did literally say those words what manayatana "intellectualises" is too often something like: "Your nose is a strawberry and your mother is defective." The word 'your' is key here because this whole P.S. chain is activated by avijja which has at its core the belief in an essential self - a me. We take it all personally. So, ayatana arises in subjection, the senses are appropriated, they are (held to be) mine. They are in effect the substantiation, the proof of my me-ness; it is through my eyes (here) that I see (hear, smell, etc.) you (out there). This relative relationship - through the senses - of me and things is phassa.

Phassa is from phusati to touch but it doesn't refer literally to physical contact. When the eye 'contacts' a visual object it obviously doesn't touch it. A better way of thinking is sense-impression, or coming-together - although we can generally use the word 'contact' for convenience.

- "There are 6 classes of sense-impression: visual impression (cakkhu-samphassa), impressions of hearing, smelling, tasting, bodily (tactile) impression and mental impression" Majjhima 9

We can see from this that phassa is invariably bound with salayatana. It is also integral to sankhara and nama and is one of the four nutriments (of life) so it is clear that in the P.S. chain we have previously made contact but that the impression has been 'formative' until now. This phase of the unfolding 'experience' is more conscious and directly observable but still has a relative nature. Experience is multi-sense based - multi-media if you like - and, following our example of being insulted, the eye-ear media are dominant and you may not notice the taste of the mint you are sucking (not a sucker? good for you :) So the previous (dominant) factors are finally formed, they come-together, - via manayatana - and give rise to feeling.

The issue of self or ego is relevant at each stage of P.S. but we can give it particular consideration here in relation to phassa and the nature of experience. For the enlightened person experience is not based on avijja but clearly there is still a conscious, 'six-based' body and... other phenomena - basically whatever is not one's body. Both are essentially objective in experience. However, for the unenlightened person, there is a strong 'aroma' of subjectivity that arises and the experience will naturally tend to be attributed to the body - my body. Phassa then becomes an experience between subject and object (me contacting it), and not an open relationship between eye, forms, and eye-consciousness. P.S. is often encountered in reverse - pointing to cessation; "cessation of death = cessation of birth... with the cessation of contact there is cessation of sense-impression... etc.. The question often arises: "how do we not contact? not feel?" and an interpretation of nihilism can take shape from here. It is important to see that it is not the cessation (or death) of the eye itself, or the body, or feelings and it is critical to remember that P.S. is all about "paccaya" - supporting conditions. The essential supporting condition is avijja - not-knowing - or wrongly believing that "I am" - the five khanda. Once we remove this condition, the subjective-objective view, the whole P.S. structure dissolves - it is the end of dukkha, and contact with the world is no longer a 'sticky' affair but a free flowing, natural process. Joy can arise, happiness can arise, rapture, etc., but they are still always dependant (on their various supporting conditions) and they can not be owned or controlled. More on this in vedana-tanha.

On a more direct level you can easily observe that when the eye (sense-base) contacts the sweet pastry (phassa) there is a feeling. The contact is still only an 'impression' - your fingers are not yet sticky. The eyes can be averted - the contact redirected. Different contact - perhaps even a different sense base - gives rise to a different feeling. Put on some music and your diet may be saved. This is not transcending avijja but is nevertheless undermining the habitual tendencies that feed avijja. It is a (small) step toward freedom. Journey of a thousand miles begins with the first step.

Vedana - feeling

When there is contact, there is feeling. When there is any form of consciousness - even of the bhavanga variety discussed earlier in viññana - there is feeling. On a basic level there are three kinds of feeling: pleasant, unpleasant and neither-pleasant-nor-unpleasant. We will use the term 'neutral' for this last form although it is not entirely accurate [more on this below]. According to its nature, feeling can be more specifically divided into five:

- bodily pleasant feeling

- bodily unpleasant feeling

- mentally pleasant feeling

- mentally unpleasant feeling

- balanced or neutral

Feeling is the common translation but we should first make clear the distinction between vedana and emotion. Usually when we ask: "how are you feeling?" we mean: "what is your emotion?" Feeling is sense based, it arises from phassa (sense-impression). As an extension of feeling, or in relation to vedana, we can talk of 'sensation' but need to see that where there are degrees of sensation there are no degrees of vedana . Pleasant feeling is pleasant - otherwise it is either unpleasant or neutral. We might qualify sensation, as the result of contact, as being mildly pleasant, very pleasant, etc. but pleasure and pain (both sensations) are not the same as pleasant-feeling and unpleasant-feeling, although they are obviously intimately related. Looking back at phassa we recall that it is not about literal physical touch but about sense-impression. However, this is actually the condition (paccaya) for "sensation degrees." The 'external bases' vary - the intensity of light, volume of sound, etc. and the 'personal bases' (ayatana) vary - the sound may be intense but the ear is half-deaf - and so accordingly do sensations vary.

Emotion is perception based - relative to memory and the result of the contact-feeling combination. Perception is basically awareness of an object's distinctive marks (one perceives blue, yellow, etc.). If, in repeated perception of an object, these marks are recognized, then perception functions as memory. Emotion is built on the collective "distinctive marks" of our experience. We remember the marks of "stick" and "for walking" and "other values." The variance of "other values" means the sight of a walking stick can bring forth, for one person, painful emotions (memories of being hit) and for another person, loving memories of a grandparent. Same stick - different feelings and different emotions. Feeling is always singular. In this second case, pleasant. Whereas emotion can be multiple: love or joy or happiness or contentment or ... there are many possibilities and many, many degrees for emotion. There is however, no such thing as "mixed feelings."

Feeling is one of the five khandhas (vedana-khandha) and as such is an integral part of being alive as a human being. Emotion is part of sankhara-khandha so is also part of our ongoing experience. Although vedana is a distinct element of experience it requires a very still and spacious mind to observe a single feeling. The supporting conditions for that feeling are inconstant so the life of what we might call 'one feeling unit' is quite brief. Consider instead observing the mood associated with contact - the prevailing atmosphere of the mind. Language limits crisp distinction but consider mood as: spirit, disposition, temperament, flavour (of mind) and allow that it has less dynamic energy than does emotion. In the recipe of life feelings (moods) are the basic ingredients - emotions are the meals on the table. Ingredients can go in many directions - soup, stew, roast... Meals only have one option - consumption.

Neutral feeling is sometimes thought of as indifferent or dull or numb but this misses the special opportunity that exists at this point of balance. Consider the following quote:

- "Lady, what is pleasant and what is painful in regard to pleasant feeling? What is painful and what is pleasant in regard to painful feeling? What is pleasant and what is painful in regard to neutral feeling?"

- "Friend Visakha, pleasant feeling is pleasant when it persists and painful when it changes. Painful feeling is painful when it persists and pleasant when it changes. Neutral feeling is pleasant when there is knowledge [of it] and painful when there is no knowledge [of it]."

Awareness of neutral feeling transforms it to pleasant feeling - and v.v. [see: Culavedalla sutta discussion § ]

Mindfulness is the path to the deathless - Unawareness is the same as death. [Dh.P.]

See also the discussion on equanimity (upekkha) in the Four Brahma Viharas [ § ]

Consider that almost all the energy of our life is spent in the pursuit of pleasant feeling and that this is, at the same time, a flight from unpleasant feeling and neutral feeling. And isn't it ironic - we can never really get there.

- "Whatever is felt is subject to dukkha. This I have regularly stated simply in connection with the impermanence of all compounded things (sankhara)." Samyutta XXXVI.11

Because our feelings and emotions are so dependant on supporting conditions (paccaya), and those conditions are regularly changing, the odds of arriving exactly where we want to be are slim. Even when we get close - blow me down but the price of oil goes up, weather turns bad, daughter gets pregnant, dog dies, debt collector calls.... - and it can incline to despair. But, there is hope - on two fronts.

- The first is simple. We are part of the process, we have the ability to intend, to participate in the flow of events. This is called kamma - action. But it is limited. There are many of us (god included?) intending in different directions. There is some kind of collective averaging - with right-view and goodness as the deciding factor (in the long run).

- The second is more challenging. Don't be a victim of feelings. This practice is the second foundation of mindfulness (satipatthana) and it begins by learning to understand the nature of feeling. If you can fully know the quality of pleasant feeling - just as feeling, before it evolves into perception-emotion - then you have the ability to observe the seed-point of perception-emotion. Feeling is one of those branches as you fall out of the tree - you can grab it! Just rest with the feeling. Strengthen the ability to just be with unpleasant feeling. Strengthen the ability to just be still with pleasant feeling - and not feel compelled to rush off in pursuit. This doesn't mean never doing anything but it does mean YOU HAVE A CHOICE. You no longer need be a victim, a slave to your memories, your childhood traumas, your perception fantasies and the like. It requires mindfulness and self-restraint.

- "All feeling -- whether of the past, the future or the present, whether in oneself or in others, whether coarse or sublime, inferior or superior, far or near -- should be seen with right understanding as it actually is: 'This is not mine, this is not me, this is not my self.'" Samyutta XXII, 59

It is difficult to be objective about emotions, to not take them personally. Because feeling is less complex we can refine awareness of our experience to the simple level of feelings. Seeing feelings as just feelings it is easier to not get caught in the complex psychological network of perceptions and emotions that arise from those feelings. The emotions are always there, hanging around the fringes of awareness, but to see clearly: "this is pleasant feeling - pleasant feeling is like this" and to see the associated habitual movement of craving. It is pleasant - and I want it! Sometimes life is difficult, beyond our current ability to effect change. Unpleasant feeling is like this. Be at peace with that. Feeling conditions craving - but feeling not taken personally can rest, just there. It may squirm a little but it need go no further.

Tanha - craving

So, you saw 'it' (or smelt, touched, heard, tasted, thought) and there was this feeling. Ever so nice it was - pleasant - and it had a little jingle: "pick me, buy me, take me home and I promise I will make you happy." Welcome to the ninth link of paticca samupadda [P.S.] - craving. Its in the shopping cart but you haven't reached the check out yet. A little voice debates as you wheel around the aisles. Part of it knows you don't need it, can't afford it, it won't go with the furnishings, your partner will complain. But the other part.... well, it is on special (limited time only), I do deserve 'something' for all my efforts, my friends will think its cool, it cuts, it dices, it slices, it will take out the garbage - and, platinum trim! Yes !

Welcome to the tenth link of P.S. - grasping. And the two mind movements are almost as one, such is the power of feeling.

First a review of tanha. It literally means 'drought, thirst' and figuratively 'the fever of unsatisfied longing.' It is well established as the second Noble Truth [ § ] - the primary cause of dukkha. In the context of P.S. it is that point beyond which there is no turning back. Once the mind has been infected by craving it is not impossible to 'say no' but it is very difficult. There is a lot about life that is difficult. We regularly experience unpleasant feeling. It is perfectly natural, and healthy, to incline away from the unpleasant toward the pleasant. So where is the problem? It is an unreflective tension between need and greed, between wisdom and desire, between being and becoming. And what fogs our mirror is tanha.

- "If this sticky, uncouth craving overcomes you in the world,

- your sorrows grow like wild grass after rain." Dhammapada 335

More often than not when we are working with our bad habits, our addictions, our cravings, it is not within the actual craving where we find release. Having set up the intention, to maybe quit smoking, there is contact (sight, smell, thought) with resultant (habitual, pleasant) feeling - and craving. The pattern has been repeatedly established: contact - feeling - craving - upadana - bhava - (re)birth as a smoker. Puff puff. Heroin addiction is sometimes talked about as 'having a monkey on your back' - it wants (regular) feeding. It gets hungry - it digs in its claws. Try and shake it off - it digs in its claws. You can't run - you can't hide. You can only let it die. Wean it off to a degree but ultimately the only solution is starvation.

We can't beat craving so what we need to do - somewhere along the chain - is cut off the conditions that lead to its arising. Several possible access points have been discussed but the most workable is vedana. The preceding chain-links of our 'momentary arising' or 'unfolding experience' are quite subtle and barely within the scope of awareness but feeling is formed, or conscious enough so that we can catch it - if we try. As a practice, it is sufficient to begin with, just noticing the attraction toward pleasant feeling (want more) and the repulsion around unpleasant feeling (want less). As this ability develops it becomes increasingly possible to just 'sit' with the feeling and not go to craving. Or, we can change the conditions, redirect attention. In effect this is substitution or distraction - a valid strategy until until right view matures. This is the critical point - developing right view (insight, wisdom, knowledge, vijja) into the workings of the whole P.S. mechanism. This 'right-view' arises through wise attention; manasikara [see: nama-rupa ].

So, see through the feeling from a perspective of vijja (not a-vijja) or just abide with the feeling or change the associative conditions. Either way, there is some conscious, intentional action and fuel is removed from the fire of craving. Do this often enough and the fire will go out - the monkey will die. This is the path toward realising the third Noble Truth: cessation of craving.

Upadana - grasping

Upadana literally means: "the basis on which an active process is kept alive or going; fuel; supply; provisions." And what is this 'active process' that we are trying to keep going? It is ME. I wander my life gathering all the material and psychological provisions that I imagine will supply me with (a sense of) constant well-being - pleasant feeling. I gather them - and I grasp them.

The most unpleasant feeling, one that we constantly face, is death. Our grasping is superficially related to pleasant feeling but essentially it is grasping life. In the 3-life model of P.S. birth, life and death are considered literally but within the this-life experiential model we look more to perceptual birth and life, to "a sense of being." And we have to be... something. Must be a somebody - if we are to be alive. Can't be a nobody - 'tis the same as death. So, the main problem of grasping is grasping various ideas of being. Being rich, being well-liked, being successful, being a failure, etc. Conditions may exist to confirm these perceptions but conditions are, well, just conditions. They are fickle. They are what you can observe - not what you are. All this pivots around the basic presumption that 'I am' - something. [see: anatta § ].

Four kinds of upadana are traditionally considered:

- sensuous clinging

- clinging to views (around kamma)

- clinging to rules and rituals (leading to freedom)

- clinging to personality-belief

The first relates to the body. The other three relate more to the self-identity issue. We each have a variety of views and opinions which directs: what to do, how to do it, and why (kamma). We have ideological positions regarding rules and due process (rituals) and we all hold to the idea that 'I am' - that this personality, this collection of conditions is me. For every day life - travel, work, family etc. - we do need a degree of discrimination and part of that faculty involves views and opinions. The problem arises when we absolutise the personal. When my personal "this is my opinion" extends to become "this is how it is" (for all) and, I cling to that postition and, I identify myself with that position. I am... a person who thinks this, does this, believes this - and... it is all solid, real, true, fixed. It is so - and I am this. There is some security in this assertive way of viewing life but it is very dependant and quite empty.

There is a paradox in relation to upadana. We need a certain amount of pleasure (joy, happiness, etc.) in our spiritual life for it to be sustainable - so we can eventually go beyond sensuality. We need views (devoloping 'right' views) to overcome our grasping of views. We need a framework of rules, rituals and precepts to support our practice - so that we can eventually transcend rules and rituals. We need a degree of personal stability and self-responsibility to overcome attachment to our doctrines of the self. We can have these things, and make use of them but need not grasp them. Finding the point of balance is part of the challenge we face.

- "When seen & heard, people are called by this name or that,

- but, after death, only the name remains to be pointed to.

- Those greedy for objects of attachment do not let go sorrow, grief and avarice,

- but sages, letting go of possessions, live in full security." Khuddaka IV.6

The suggestion in relation to grasping is letting go. And what do I let go of? Absolutely, completely everything - grasp at nothing.

- But, won't I just... disappear? If I hold nothing then won't I be nothing?

- Consider that, try as you might, you can't hold anything any way. Conditions change. We are all, in some respects, playing the game of life. Why not play to win? Sure, but the more we grasp at outcomes the more we will suffer. Even if the outcome arrives according to our craving it can be so wrapped up in anxiety and tension that we are often not able to fully enjoy it. Sometimes we win, sometimes not - don't attach to either gaining or losing - just move on.

Bhava - becoming

From craving arises grasping arises becoming. bhava: Becoming. States of being that develop first in the mind and can then be experienced as internal worlds and/or as worlds on an external level. There are three levels of becoming: on the sensual level, the level of form, and the level of formlessness. 'becoming', 'process of existence', consists of 3 planes: sensuous existence (káma-bhava), fine-material existence (rúpa-bhava), immaterial existence (arúpa-bhava). Cf. loka. or: sensual existence, deva--corporeal, & formless existence kamma° and upapatti° (uppatti°), or the active functioning of a life in relation to the fruitional, or resultant way of the next life --anga constituent of becoming, function of being, functional state of sub- consciousness, i.e. subliminal consciousness or sub- conscious life--continuum, the vital continuum in the absence of any process [of mind, or attention] (thus Mrs. Rh. D. in Expos. 185 n.), subconscious individual life. --äsava the intoxicant of existence --cakka the wheel or round of rebirth, equivalent to the Paãicca--samuppäda "And how is there the yoke of becoming? There is the case where a certain person does not discern, as it actually is present, the origination, the passing away, the allure, the drawbacks, & the escape from becoming. When he does not discern, as it actually is present, the origination, the passing away, the allure, the drawbacks, & the escape from becoming, then -- with regard to states of becoming -- he is obsessed with becoming-passion, becoming-delight, becoming-attraction, becoming-infatuation, becoming-thirst, becoming-fever, becoming-fascination, becoming-craving. This is the yoke of sensuality & the yoke of becoming." Anguttara Nikaya IV.10 Disenchantment is the supporting condition for dispassion": In the trail of disenchantment there arises a deep yearning for deliverance from the round of samsaric becoming. Previously, prior to the arrival at correct knowledge and vision, the mind moved freely under the control of the impulses of delight and attachment. But now, with the growth of insight and the consequent disenchantment with conditioned existence, these impulses yield to a strong detachment and evolving capacity for renunciation. "His heart, thus knowing, thus seeing, is released from the effluent of sensuality, released from the effluent of becoming, released from the effluent of unawareness. With release, there is the knowledge, 'Released.' He discerns that, 'Birth is no more, the holy life is fulfilled, the task done. There is nothing further for this world." Digha Nikaya - Samaññaphala Sutta Nothing else in the cosmos has caused us to experience becoming and birth, and to carry the mass of all sufferings, other than this avijja-paccaya sankhara.