Zen and other Buddhist sects in Japan

by Jeffrey Hays

The main Japanese Buddhist sects—Shingon, Tendai, Pure Land Nichiren, and Zen—sprung up during the Heian Period (794-1185) and Kamakura Period (1192-1338). The first homegrown Buddhist sects to take hold in Japan were the Tendai and Shingon schools.

Most of these sects are followed by a relatively small group of people today. The sects that grew out of them have larger followings.

For many Japanese, all sects are the same and they have little understanding of the differences between them.

The Tendai sect is an eclectic form of Buddhism that incorporates elements of both Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism. The Lotus Sutra is Tendai’s central text. Followers believe that salvation can be achieved by reciting and copying it.

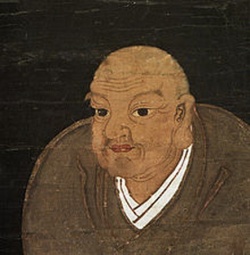

The Tendai sect appeared at the end of the 8th century and was centered at Enryakuji Temple on Mt. Hiei near Kyoto. Its founder, Saicho (762-822), studied meditation, tantric rituals and the Lotus sutra under the Tient-tai School in China—named after Mt. Tientai in what is now Zhejiang Province—for two years in 804 and 805. When he returned to Japan he found a receptive audience for his message that Buddhist salvation was something that could be achieved by anyone, regardless of class, social status or gender. Saicho is also known as Dengyo Daishi.

Under the patronage of Emperor Kanmu (737-806) and Emperor Saga (786-842) the Tendai sect was officially sanctioned. It was embraced by these emperors who had tired of the authoritarian nature and political power of the priests in the Nara Buddhist sects. Priest were ordained at Enryakuji, the temple founded by Saicho, Tendai artists produced wonderful Buddhist sculpture—graceful and beautiful sculptures of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas and deities—in the Heian period.

Tendai was not recognized as a school until after Saicho’s death. After Mt. Hiei received the right to ordain monks the sect took off, At it height Mt, Heie boasted 3,000 temples and 30,000 monks and produced wonderful works of art. The monasteries kept armed retainers and sometimes imposed their will on the government by force.

Almost every sects has its origins in a temple on Mt, Heie. All new sects founded din the 12th and 13th centuries were founded by Tendai monks. Pure Land, Zen and Nichiren all developed from the Tendai school.

Shingon Buddhism (whose name was derived for the Sanskrit word for "magic formula" or "mantra") is centered at Kongobu-ji Temple at Mt. Koya and To-ji Temple in Kyoto. It is closely linked with the Tendai sect and is known for its ornate art and incorporation of Shinto elements. Today there are 3,700 Shingon-affiliated temples nationwide.

Shingon Buddhism has Tantric elements and is known for it rich ceremonies and has many similarities with Tibetan Buddhism. A central idea is to find the "mystery at the heart of the uncovered” using rituals, symbols and mandalas representing the sphere of the indestructible and the womb of the world.

Shingon Buddhists practice takigyo— standing under freezing cold waterfalls at Hakuryu Bentenzan Shumpukuin temple in Mikumocho, Mie Prefecture and the Oiwasan Nissekiji Temple in Kamiichimachi in Toyama, Prefecture as part of an ascetic purification ceremony to mark the beginning of the coldest time of the year. Participants wear white gowns and headbands and chant as they stand under the waterfalls. Sometimes they chant as conch shells are blown. . Sometimes they for stand for over an hour in freezing water.

At Oiwasan Nissekiji Temple pilgrims pray for good health while standing under a waterfall in early January on a day traditionally regarded as the coldest day of the year. In 2009 about 60 people took turns standing under the six-meter-high waterfall in -3 degree C weather chanting Buddhist sutras.

In April 2009, a professional boxer died while doing training at a temple waterfall. It is believed he accidently fell in.

Kukai (774-835), the founder of Shingon Buddhism, is one of Japan's most beloved religious figures. Born in Shikoku, he studied at the Imperial University and spent some times as a wandering monk and mountain ascetic and died at Mt. Koya. He is revered as a scholar, Bodhisattva, artist, calligrapher and inventor of the 47-symbol Japanese Kana symbols and is credited with merging the deep spirituality of someone who meditating for long periods in a cave with rituals and discipline of Tang-era Chinese esoteric Buddhism. He remains a popular folk hero. In some stories he is merely sleeping in his tomb in Mt. Koya and will rise up again some day.

Kukai was a friend of Saicho’s who traveled to China in 802, the same year Saicho did, but went not to Mt. Tientai but to Changan (Xian), the capital of China, where he was influenced by Mikkyo (Esoteric Buddhism) and the Chinese Chen-yan school. In China, it is said, Kukai learned Sanskrit and all the secret teachings and doctrines of Tantricism and Esoteric Buddhism in the amazingly short period of three months to two years, depending on the source.

Upon his return to Japan in 807, Kukai secluded himself in mountain ashrams at Mt. Misem on Miyashima Island near present-day Hiroshima and was forced to stay in Kyushu for breaking an agreement to stay in China for 20 years. During this time Kukai and Saicho exchanged infromation on what they had learned at their respective destinations in China. Kukai left Kyushu with Saicho’s help and was initiated into Esoteric Buddhism. Kukai and Sacho had a falling out when Kukai started propagating his own teachings. Each considering the other a disciple not an equal. After Saicho’s death in 822, Kukai’s influence grew.

Kukai decided to establish his headquarter at Koysan, the Buddhist priest Shodo Habukawa told the Daily Yomiuri, because it was a place where he could feel the connection between the sky and the earth...The basin is surrounded by two circles of mountains and the inner and outer circles have eight peaks each. The area resembles a lotus flower.”

Kukai, was very influential in court politics. He helped reconcile Buddhist sects with each other and with Shinto. After his death he was given the name Kobo Daishi.

Pure Land Buddhism (also known as Jodo, Jodoshu, or Jodoshinshu) spread during the Kamakura Period (1185 to 1333) but was introduced by the Chinese to Japan much earlier. Today it has 6 million followers and 7,000 affiliated temples across Japan and has a large following among ordinary Japanese. Pure Land is another word for heaven.

The School of Pure Land emerged about A.D. 500 in China as a form of devotion to Amitabha, the Buddha of the Western Paradise, and differs from the Ch'an school in that it encourages idolatry. The School of Pure Land is not nearly as strong in China as it once was but it remains one of the largest Buddhist sects in Japan.

The School of Pure Land takes the Mahayana belief in Buddhas or Bodhisattvas a step further than Buddhist traditionalists want to go by giving Bodhisattvas the power to help people attain enlightenment that otherwise would be unable to attain it on their own. The emphasis on Bodhisattvas is manifested in the numerous depictions of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in Pure Land temples and caves.

Pure Land Buddhists reveres Amida (literally meaning “infinite light” or “infinite life”), the Buddha of the Western Paradise, and stress the universality of salvation. They believe that salvation is achieved through faith rather than good works and that Buddha and heaven are close at hand and everywhere rather in some far off place as Buddhists had been taught to believe.

Pure Land Buddhists believe that Buddhism has entered a Mappo (Later Age) in which Buddhism is in decline and individuals are no longer able to achieve enlightenment on their own and salvation can only be achieved by enlightenment through the mercy of Amida. This idea appealed to many ordinary Japanese who were not turned on by an usual process of mediating, chanting and denying oneself for long periods of time.

Honen (1133-1212), the Japanese man who made Pure Land Buddhism an independent sect, eschewed scholarly metaphysics and promoted the use of simple prayers and chants such as "Hail Amida Buddha," as a means to enlightenment. He once said "Even a bad man will be received in Buddha's Land, but how much more a good man!" The idea of hell and judges is important in the Pure Land school of Buddhism.

Honen studied as a Tendai monk at Enryakuji Temple on Mt. Hiei, beginning at age 13, and read the Chinese Tripitaka five times and was respected for his learning. He began teaching the Pure Land faith after realizing, at age 43, that the teachings of the Buddhist elite were lacking and that reliance on Amida was the only way to reach enlightenment and it was something that could be obtained by anyone not just pious monks. This message appealed to both the elite and ordinary people but was opposed by the old schools.

Honen and his followers were persecuted. At the age of 75 Honen was banished to Shikoku. Some of his followers were executed.

Shinran (1173-1262) was one Honen’s favorite disciples. He is regarded as the actual founder of the Pure Land sect in Japan. He renounced the monk’s life and married a young noblewoman, arguing that celibacy and dietary rules demonstrated reliance on self-power. He was banished and spent much of his life in the provinces. His grandson carried on his lineages, which remains alive among his descendants today.

The Pure Land sect became very powerful when it was adopted by the ancestors of Tokugawa Ieyasu, Japan’s first shogun. Ieyasu himself reportedly hand-copied the nenbutsu prayer every day on a small piece of paper. Ieyasu’s descendant turned some of Pure Land temples into military fortresses with cannons, high walls and gates.

Nichiren Buddhism—the largest of the early sects that remains active today— was founded in the 13th century by Nichiren (1222-82), an intolerant Japanese monk who promoted the Lotus sutra as the "right" teaching, and believed that violence was sometimes justifiable. His main claim to fame was predicting the Mongol invasions.

The son of a fishermen, Nichiren entered a monastery as a boy and was kicked out at age 31 for his militant views. Although he played a role in preparing Japan for the Mongol invasion, he was exiled twice for getting people riled up with doomsday predictions. In his memorial Establishing Right and Making the Country More Secure he insisted that there must be a national religion and all other sects should be suppressed. He called the Pure Land sect the Everlasting Hell and claimed Zen Buddhists were devils. Although he was condemned by the government and the traditional sects he was popular among ordinary people.

Nichiren Buddhism grew in influence over the centuries. It was based in an interpretation of the Lotus Sutra, the central text of text of Tendai and became linked with samurai and the unity of the state and religion. Many present-day Buddhist sects have their roots in Nichiren Buddhism.

Zen Buddhism evolved out of the Ch'an School, a Buddhist sect that was founded in China in the A.D. 8th century. Ch'an is pronounced Zen in Japanese. It means "contemplation" or "mediation."

Zen Buddhism was introduced to Japan from China during the Chinese Sung Dynasty in the 10th century by a Chinese monk named Huineng. It had a relatively small following for two centuries and didn't take hold and flourish in Japan until the 12th century.

The Ch'an sect’s origins are obscure. It is it not clear whether its early patriarchs were legendary or real. Under the leadership of its sixth patriarch Hui-neng (A.D. 637-723) it grew from a cult with around 500 members to a distinct sect after Hui-neng spent 15 years meditating in the hills.

Once Zen Buddhism took hold in Japan had a profound influence on the Japanese. Its austere tone and the simplicity of the doctrine appealed to the military class and artists and was a focal point of samurai culture and art from the 12th century onward. Not only that, Zen Buddhists helped bring Chinese philosophy, especially Neo-Confucianism, to Japan and were involved in commercial endeavors, such as shipping lines, that controlled trade between Japan and China.

Samurai were trained by Zen Buddhist masters in meditation and the Zen concepts of impermanence and harmony with nature. The were also taught about painting, calligraphy, nature poetry, mythological literature, flower arranging, and the tea ceremony, which all had Zen overtones. Even swordsmanship and the martial arts were steeped in Zen and ascribed to philosophies that were very esoteric and hard to understand.

In the early days there were who two competing schools of Zen Buddhism: Soto, which emphasized mediating in the seated position under strict guidelines, and Rinzai, which emphasized lengthy question-and-answer drills and the contemplation of koan (metaphysical riddles that have no logical answer) such as "What is the sound of one hand clapping?"

The Rinzai sect, the oldest of the Japanese Zen sects, was founded in the 12th century by Myoan Eisai (See Below). The Soto Zen sect was founded by Dogen (1200-1253), a student of Eisai who also studied in China. It emphasizes shitan taza (literally "just sitting"). Sometimes trainees of the Soto Zen sect a make a vow of silence and spend their time meditating, studying and eating in silence. There are 15,000 Sato Zen temples in Japan today.

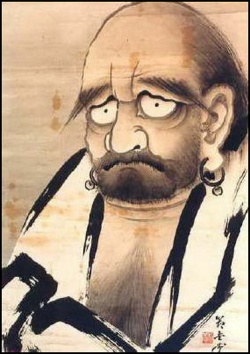

The Ch’an school is said to have been founded by Bodhidharma, a south-Indian prince who became monk and traveled to China around A.D. 520. It is not clear whether he was a real person or not.

According to legend, when Bodhidharma arrived in the Chinese capital of Nanking, the devout Chinese Emperor asked him how much merit he had earned building temples and copying scripture. Bodhidharma replied: “No merit at all...All these are inferior deeds, which would cause the doer to be born in heaven or earth again. They will show the traces of worldliness. They are like shadows following objects. A deed of true merit is full of pure wisdom and is beyond the grasp of conceptual thought. This sort of merit is not found in any worldly works.” The Emperor then asked what is the holy truth? Bodhidharma replied: “Great Emptiness, and there is nothing in it to be called holy.’ The emperor then asked him who was. Bodhidharma said; “I do not know.”

After this sharp condemnation of the pursuit of merit as basically selfish and self-indulgent, Bodhidharma left for northern China and meditated for nine years by staring at the wall of a cave. He sat there so long in meditation it is said that his legs fell off. To battle his occasional bouts of drowsiness he cut off his eyelids so his eyes wouldn't close.

While Bodhidharma was meditating a monk named Hui Ko came to visit him and seek the answer to troubling questions and calm his mind. Initially Bodhidharma was so absorbed in mediation that he did not notice the monk. Hui Ko waited in snowdrifts for some time but received no response. Finally he cut off his arm and gave it to Bodhidharma who at that point gave his attention to the monk. Hui Ko received the advise he sought and later became the second patriarch.

Bodhidharma is associated with ascetic discipline, serious mediation, yoga, psychic power and the Shaolin school of martial arts. He said: “A special tradition exists outside the scriptures, not dependent on words or letters; pointing directly into the mind, seeing into one’s own nature and the attainment of Buddhahood.”

Daruma dolls are red, round dolls named after Daruma> They commonly sold around New Year with both eyes painted over. One eye is unpainted when making a wish. The second eye is unpainted when the wish comes true. Daruma dolls have wide open eyes and fierce scowl that are intended to keep evil spirits and demons away and bring good luck. They have no legs because Daruma sat so long in meditation that his legs fell off. Daruma himself is featured in both 15th century paintings and 21st century television cartoons.

Important Figures in Zen Buddhism in Japan

Three of the most important Japanese figures in Zen were Ikkyu, a hard-drinking womanizer who thumbed his nose at authority but demonstrated great incite into Zen through his poetry and calligraphy; Hakuin, who developed an influential theory of enlightenment and style of teaching; and Ryokan, a wandering poet who expressed Zen virtue through his simple and contemplative poetry and lifestyle.

Lanxi Saolong, a Chinese Zen master known in Japanese as Rankei Doryu, is credited with making Zen a credible religion in Japan. He arrived from China in 1246 and was welcomed in Kamakura by a powerful feudal leader there. He purified the forms of Zen that were practiced, was involved in establishing the Rinzai school of Zen, and helped spread it throughout Japan.

Dogen Zenji (1200-1253) founded the Soto Sect and Eiheji Temple in Fukui Prefecture. Born to noble parents that died when he was young, he traveled to China when he was 24 and underwent strict training with a famous Zen master. He returned to Japan in 1228 and lived at Kenneinji temple in Kyoto for three years before founding his first temple in Uji, near Kyoto. In 1244 he and his followers founded Eiheji in the mountains of Fukui Prefecture. Eiheji means “eternal peace.”

Eisai (1141-1215) is also known as Minnan Yosai. Born into a samurai family from Okayama, he studied with the Tendai sect and made two visits to China and is well known among Japanese for introducing tea culture to Japan. His sect gained strength after being supported by the Kamakura period shoguns.

Eisai entered the priesthood at age 14. He studied ay Enryakuji temples, the headquarters of the Tendai sect on Mt. Hiei, but left after becoming disillusioned with the decadent behavior of the monks there. He embarked on his first trip to China in 1168 at the age of 28 to visit Mt. Tientai in what is now Zhejiang Province to study the Buddhism that was imported to Japan 350 years before. He found that the Buddhism at Mt. Tientai had been supplanted by Chinese-style Zen (Ch’an) Buddhism and returned home gravely disappointed.

Eisai embarked on his second visit in 1187 with the plan to visit the entire Buddhist world and absorb ideas on how to reform Buddhism in Japan. Authorities in China however would not let him venture beyond China so he returned to Mt. Tientai and talked to monks at Wannian Temple there and found out that the answers he was seeking could be found in Zen. The temple was surrounded by tea gardens so he learned about tea as well as religion.

During Eisai’s effort to spread the word of Zen, first in Kyushu and then in Honshu, monks at Mt. Hiei persecuted him and banned his Zen missionary work in 1194. After Eisai’s teachings were supported by the Kamakura shogunate a major Zen temple, Kenniniji temple, was founded in Kyoto.

Zen emphasizes intuitive insight and living for the "here and now." The idea of Zen is not to do something deliberately or with intent, but rather to remove yourself from what you are doing at let "higher forces" guide you. Zen looks down on the use of logic, intellect, idolatry and sacred texts and stresses self-reliance and meditation and emphasizes concrete thought over metaphysical speculation.

The aim of Zen Buddhism is to purify the soul and achieve salvation through inner enlightenment, something that happens for brief instant after 15 or 20 years of meditation. To reach the state of enlightenment, an individuals must unite his or her body and mind with the forces that drive nature. On the journey to enlightenment, Zen Buddhists believe, each level of achievement is just as important as the final state of divinity reached at the end.

Zen emphasizes teachings transmitted from master to disciple rather than a dependance on texts or iconography.

Many ascetic holy men in Japan, known as hijiri, are Zen Buddhists. Followers of a strict discipline called the "ascetic way," they hope to acquire superhuman powers through the attainment of merit, attending shrines, working as shaman and seeking "ecstatic inspiration" by climbing mountains.

One man who who sought out this way of life told National Geographic, "I felt nothingness and that was valuable but I would not go back to the yamabushi life [[[life]] of the mountain ascetics]. There was no newspaper, no TV. Fasting I can tolerate, but no information makes me restless." [Source: Patrick Smith, National Geographic, September 1994]

Some Zen Buddhists engage in highly ritualized behavior. Priests in the Soto Zen sect, of example, only bath on dates that include a four or nine. Before they bath they bow three times and say, "We bath vowing to benefit all beings: may pure bodies and minds be purified both inwardly and outwardly."

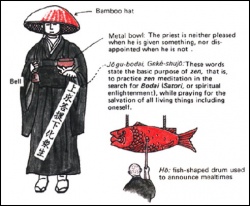

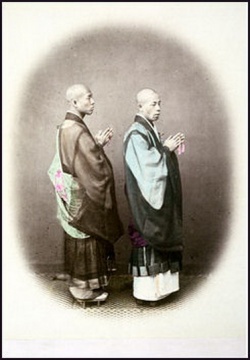

Zen monks usually have a shave head and wear black robes and white tabi (socks). They sometimes go out begging. It is not so important whether they collect anything or not. What matters is the act of begging.

Monks in the Soto sect are expected to adopt one of three basic poses at all times. When standing or walking they are supposed to adopt the shashu pose in which both hands are held over the heart with elbows horizontal and the left hand formed into a fist with right hand placed on top of the fist. The posture represents concealing one’s ego.

Zen Aesthetics and Meditation

Zen stresses meditation and disciplined aesthetics expressed through traditional Japanese arts such as the tea ceremony, landscape gardening, archery, flower arranging or doing things like playing a shakuhachi flute with a basket over one's head. The calm orderly nature of these activities is supposed to free the mind and induce an inner sense of calm.

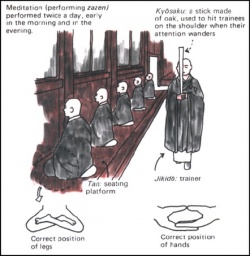

On his experience learning how to meditate at Eiheji Temple in Fukui Prefecture, Kenicho Okumura wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “I sat on a tatami straw mat with legs folded tightly beneath me. I was told to meditate for 20 to 30 minutes, and for all of that time I was supposed to clear my mind of all thoughts other than the fact I was sitting...This proved difficult. Many things popped into my head, from family members to the almost intolerable pain in my legs. An observing priest must have detected my lack of concentration as at one stage he delivered a sharp reprimand by whacking me on the right shoulder with a paddle.”

The concept of clearing one’s mind was articulated by Dogen Zenji (1200-1253) as shikantaza. Meditating monks are taught to cast their eyes downward, assume the lotus position, keep their backs straight, breath rhythmically, block sensation and attempt to clear their mind in such a way that enlightenment is allowed to grow out of the state of nothingness. If novice monks droop their head or fall asleep while mediating their instructor whacks them on the shoulder with a stick, telling them to "concentrate."

Zen is often applies to the arts. The shakuhachi, a kind of flute that arrived in Japan via China about 1,400 years ago, has a long association Zen and is said to have a meditative quality because its sound is so closely linked with human breath. Patterson Clark, an American who studied the shakuchi in Japan, told the Washington Post, the shakuhachi is “notoriously difficult to play...It forces a face-to-face confrontation with expectation, self-criticism, disappointment, frustration, and impatience—all in a single breath. Exhaling through all these impediments and releasing one’s attachments to them can dissolve the ego so that one experiences only the sound—and become the sound.”

Zen also teaches that every act in life, even mundane activities from of everyday life like eating and bathing and doing chores, are directly related to Zen practice and Are regulated by zen.

Zen, Western Culture and Motorcycle Maintenance

Zen caught the interest of Beat writers and Abstract Expressionist painters in the 1950s and has been an object of counterculture fascination ever since. These days Japanese salarymen are turning to Zen to build disciple and alleviate stress and help them get thoughts of work out of their minds.

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (1974) by Robert Pirsig was a big hit in the United States as the glow was wearing off the 1960s and has sold more than 5 million copies as of 2009. In it Prisig uses a motorcycle trip from Minnesota to San Francisco to illustrate the principals of his “Inquiry into Values” theorem which he felt transcended the Western notion of emotion versus intellect, technology over romanticism and the like and focused on the idea of “Metaphysics of Quality” which paraphrased is basically the notion that the only job worth doing is one done well.

Before the book Pirsig was institutionalized and forcibly given electroshock therapy.. Afterwards he devoted much energy to battles within the University of Chicago philosophy department which Pirsig described as a high drama “featuring a rebel genius against the tenured forces of dankness.”

Life in a Japanese Zen Monastery

At Eiheji Temple in Fukui Prefecture, monks wake up at 3:30am in the summer and 4:30am in the winter. They are allowed a single bowl of water with which to wash their face and clean their teeth. After that they spend 40 minutes meditating and one hour to 2½ hours at a morning service.

Breakfast usually consists of rice with soup and pickles. The better part of the morning is taken up with chores such as cleaning corridor floors or working in the garden. Cell phones, televisions and newspapers are forbidden, On monk told the Daily Yomiuri he didn’t find out about a Prime Minister resigning until two weeks after the fact when he saw news about on scrap newspapers he was using for cleaning.

Describing his experience at a Zen monastery Patrick Smith wrote in National Geographic: "I ate an austere dinner of rice and fresh, cold vegetables. Under the watchful eye of a youthful priest-trainee, I spent 30 minutes at zazen meditation that evening. Before I could begin it took him that time to get my position just right—legs properly crossed, hands correctly placed, head at the desired angle. Then I was to follow my thoughts wherever they led. I slept on a tatami mat on the floor." [Source:"Inner Japan" by Patrick Smith, National Geographic September 1994]

"At 3:30 the next morning," Smith continued, "I was awakened and led to a room where row upon row of priests, kneeling on a vast spread of tatami, were softly chanting a Buddhist sutra. So the monastery began its day. It was cold and breakfast (as austere as dinner) was hours away; hunger gnawed at my attention, and my eyes wandered across the old plaster walls and the heavy ceiling beams, darkened by the smoke of countless sticks of incense."

Monks often spend a lot of time sweeping, scrubbing floors and cleaning. These activities are regarded as part of their monastic training. One monk told the Daily Yomiuri he didn’t mind that, “The shortage of sleep still annoys me most, although I have become used to other hardships.”

Shugendo and Mountain Asceticism in Japan

Shugendo is the religion of Japanese mountain ascetics. A unique blend of indigenous Japanese beliefs with Taoist and Buddhist elements brought from China, it is regarded as an esoteric Buddhist school that combines Buddhism with ancient Shamanist practices and Shinto beliefs. It was founded by Enno-Gyoja, an ascetic who is said to have had magical powers and is credited with enlightening kami about Buddhism. Enno-Gyoja sat the summit of a mountain called Sanjogdake, chanting Buddhist sutras, for 1,000 days, until he reached an elevated level of spirituality and evolved into the Kiongo Zao ai Gongen deity to end human suffering.

Japanese mountain asceticism merges Shintoism, Taoism, Buddhism, animism and Japanese folk religion. In the old days, mountains were viewed with awe and fear because of their association with the gods and the dead. Beginning in the A.D. 7th and 8th centuries, mountain ascetics began climbing mountains in an effort to tap into the power of kami. Some scholars trace the origins of Japanese mountain asceticism to Chinese Taoism. The first mountain ascetics were Buddhists and Taoists who absorbed local kami—that local Japanese believed dwelled in the mountains—into their beliefs.

Shugendo evolved in the Katsuragi mountains between Osaka and Nara then moved on to the higher peaks of Yoshino in Nara Prefecture. Early yamabushi sought not only spiritual enlightenment but attempted to obtain magical powers that could be used to heal the sick and prevent disasters.

Practitioners of shugendo are called Shunenja or Yamabushi, Information on shugendo is limited because the sect is very secretive. Followers learn about plants, mountains and animals and use this knowledge for the betterment of humanity. Their rituals have been described but the mechanisms behind them are still sheathed in mystery. The cult has also been compromised by tourism and modernism.

Yamabushi are Shugendo mountain ascetics. Also known as shugenja, they are members of Esoteric Shingon and Tendai sects of Buddhism. Traditionally they were shaman or hermits with long beards who lived in huts on sacred mountains and endured rigorous training and exercises. Yamabushi means “those who lie down in the mountains.”

Early yamabushi went on long treks and mountain climbs and lived for months and even years in the wilderness. Their training and lifestyle were believed to have given them magical and supernatural powers. Villagers welcomed them so they could perform rituals to prevent earthquakes and other natural disasters and bring rain and good harvests.

Yamabushi wear a distinct costume that consists of a white tunic and super baggy pants stuffed into cloth boots. They have black lacquered cups strapped to their forehead, two furry pom poms dangling from the neck, a variety of trinkets hanging from their waist and a huge conch shell at their side. The often have deer pelts on the seats of their pants and a carry ringed or wooden staff.

Before the Meiji period, many ordinary Japanese sought out yamabushi in the mountains because they were believed to have supernatural skills and powers of exorcism. During the Meiji Period, yamabushi were banned as quacks as part of Japan's effort to modernize and promote Western medicine. Under State Shintoism, Shugenda was classified as impure. These days few yamabushi live in the mountains full time. Most are part times who, like other Japanese, carry business cards.

Shugendo incorporates elements of esoteric Tibetan-style Buddhism, Shintoism, animism and shamanism. Central to their religion is the recognition of strong powers found within mountains and a belief in death and rebirth experiences. Individual soul searching and direct interaction with the spiritual world is emphasized while Ideology, religious hierarchies and interaction with priests are downplayed.

Most yamabushi learn simple spells and chants to enlist the help and protection of deities. A great deal of time and devotion is required to learn the secret magical mudra (“positions”) which allows them to merge their spirit with that of a deity, giving them the power to disappear and perform other difficult tasks.

Yamabushi beliefs emphasize mediation and liberation through doing difficult tasks. In the old days yamabushi run all day through the mountains for 1,000 days. They also engaged in firewalking and chanting under freezing cold waterfalls.

The Yoshino area, near Nara and Osaka, was a major yamabushi stronghold. There mountain ascetics had to walk the 24 kilometer distance between Tenkawamaru and 1,719-meter-high Mt. Sanjodadake everyday for 100 days. During the first 50 days they were given two days to make the round trip During the second 50 days they had to the round trip trek in a single day, stopping at more than 20 small hokora shines along the route to chant sutras.

Yamabushi also believe that devotees must spend a long time in the wilderness to absorb the power of nature by living trees, animals, mountains, waterfalls and rocks. Holy mountains are believed to have special powers associated with characteristics such as size and dominance (like Mt. Fuji) or the presence of imposing cliffs or dense forests.

Shugendo devotees must observe strict ascetic rituals that have traditionally been held deep in the mountains. They seclude themselves in the mountains for months or years at a time, walking for days on end, praying, performing fire rituals, fasting in caves and subjecting themselves to various physical and psychological hardships, such as hanging off of cliffs or standing under waterfalls. In a bizarre yamabushi purification ritual, acolytes and ordinary people are held headfirst over the edge of a cliff at Mt. Omine near Yoshino to contemplate the transient nature of life and repent their sins. It is belied that people who don't repent are burdened with an extra load that will cause them to fall to a body-breaking death.

Describing the experience Doug Ogata wrote in Kansai Time Out, "Everything happened so quickly. They passed my arms through the loop of the rope and made me clasp my hands. 'Whatever you do. keep them clasped.' was the advice of the second monk as he gestured for me to get on my stomach and inched my way off the cliff. Then he grabbed my ankles and helped me forward."

"Before I knew it I was upside down, a vast gorge above my head and the wind whistled around me. The leader monk had fastened a rope to his waist. He was the only thing keeping me from plummeting to my death." Only after Ogata promising to respect the earth and his parents was he pulled back from abyss.

In another bizarre yamabushi ritual, acolytes and ordinary people are ensconced in complete darkness to simulate death and then suddenly exposed to bright lights and the sound of crashing bell to simulate rebirth. The scholar Carmen Blacker described the experience as "awakening by shock to the ultimate Emptiness of our natures."