Clearing Up Uncertainties About Basis and Expression

These excerpts are from Dakpo Tashi Namgyal's Clarifying the Natural State, which is a commentary to his work, Mahamudra: The Moonlight - Quintessence of Mind and Meditation; keep in mind, this is skipping stages of meditation, which precede these instructions.

Clearing Up Uncertainties About Basis and Expression

This has four points:

Resolving that thoughts are mind

Resolving that perceptions are mind

Investigating the calm and the moving mind

Resolving that all experience is nonarising

Resolving That Thoughts Are Mind

Assume the same posture as before. Let your mind be evenly composed as aware emptiness. From within this state project a vivid thought, such as anger. Look directly into it and thoroughly investigate from what kind of substance or basis it arose.

Perhaps you suppose that it arose from this state of empty and aware mind itself. If so, examine whether it is like a child born from its mother or like light shining from the sun. Or is it the mind that becomes the thought?

Next, observe the way in which it remains. When it appears in the form of anger, examine whether this anger is accompanied by the fetter of intense clinging to things as being real or whether it is simply an appearance of anger, an openness in which there is no identity to take hold of.

Finally, observe how a thought departs. Is the thought stopped or does it dissolve? If it is stopped, who stopped it or what circumstance made it stop? If it dissolves, examine whether it dissolves due to some circumstance or whether it dissolves by itself.

In the same way, a variety of gross and subtle thoughts should be examined to gain some experience. If the meditator holds a wrong understanding, it should be eliminated with a counter-argument and a hint given. After that, the meditator should once more continue examining.

You may not have found that the thought arose from a particular location in a particular way, that it dwells in a particular shape or form or that it departs to a particular place. Nevertheless, your concepts about whether thought are mind are different, whether they are related as inside and outside, or as the body and its limbs and so forth must be destroyed. You must experience that the various thoughts, in whatever form they arise, are an empty appearance and not a definable entity. You must recognize that they arise out of yourself and dissolve into yourself. Since mind is unconfined, you must become certain that it is mind that merely appears or is seen as being thoughts. You must resolve that thoughts and mind are indivisible.

Take the metaphor of a wave on water. The wave is nothing other than the water, and yet it is seen as a wave. Although it appears as a wave, it has never changed from being of the nature of water. In the same way, with the various types of thoughts, from the very moment they appear, they are nothing other than the aware emptiness of unidentifiable mind.

Moreover, since this mind is unconfined, it does appear as a variety of thoughts. Even though it appears as them, it has not changed from being the aware emptiness of the mind that is not a definable entity. You must settle this point decisively. You must gain the experience of certainty in the fact that the various types of thoughts are mind.

Similarly, give rise to a happy or a sad thought and investigate whether there is any difference in their identity. In this way, also become certain in regard to opposing types of thoughts."

Investigating the Calm and the Moving mind

Maintain the same physical posture as mentioned before. Let your mind be serenely calm in the state of aware emptiness. Now, investigate by looking directly into it.

While in this state of serene calm allow a thought to vividly stir. Investigate it too by looking directly into it.

Next, investigate the two instances of calm and thought movement to see if there is any difference in their arrival, remaining and departure or in their definable identity.

If there is a difference between remaining calmly and an abrupt movement of thought, examine to see if their difference consists in being better or worse, empty or not empty, having or not having an identity, and between being or not being identifiable.

If there is no difference, investigate to see if their lack of disparity consists in being identical or in being similar while different.

If identical, investigate how they are identical at the beginning, middle and end. If similar, examine how they are similar. Investigate in this way to gain some experience.

In case an incorrect understanding is held, it should be stopped with a counter-argument, a hint should be given and the investigation resumed.

Turning away from the belief that these two -- serene calm and abrupt thought movement -- are of entirely different substances, you must experience that they are the same mind, the mind that is identical in being rootless and intangible, and in being an aware emptiness that is self-knowing and naturally pure.

This being so, whichever of the two happens, there is no need to accept or reject, repress or encourage. Rather, you should become confident that this aware emptiness is naturally free -- in the very stillness when calm and in the very arising when thoughts occur."

Steps of Pointing-Out Instruction

This has two parts:

Pointing out innate mind-essence

Pointing out innate thinking

Pointing out innate perception

Pointing Out Innate Mind-Essence

First, when giving the pointing-out instruction, no one else should be present besides the master and disciple. If you prefer, assume the posture as before. Then the master says:

"Let your mind be as it naturally is without trying to correct it. Now, isn't it true that all your thoughts, both subtle and gross, subside in themselves? Rest evenly and look to see if this mind doesn't remain calm in its own natural state."

The master lets the disciple look.

"That's called shamatha...."

"During this state, do not become dull, absent-minded or apathetic. Is it not true that you cannot verbally formulate that the identity of this mind is such-and-such, nor can you mentally form a thought of it? Rather, isn't it a totally unidentifiable, aware, unconfined and lucid wakefulness that knows itself by itself?

"Within the state of evenness, look to see whether it isn't an experience without any 'thing' experienced."

The master then lets the disciple look.

"That's called vipashyana."

-

"Here, these two are mentioned sequentially, but in actuality this kind of shamatha and vipashyana are not separate. Rather, look to see if this shamatha isn't the vipashyana that is an unidentifiable, self-knowing, natural awareness. Also look to see if this vipashyana isn't the shamatha of abiding in the natural state untainted by conceptual attributes. Rest evenly and look!"

The master lets the disciple look.

"That's called the unity of shamatha and vipashyana."

-

"Both are contained within your present mind. Experiencing and recognizing this is called the birth of meditation practice.

"This is what is given many names, such as buddha-mind, mind-essence of sentient beings, nonarising dharmakaya, basic natural state, innate mind, original wakefulness, Mahamudra, and so forth. And this is what all the sutras and tantras, true treatises and instructions aim at and lead to."

-

Having said this, if the matser prefers, he can inspire further confidence by giving relevant quotations from the scriptures. Otherwise, it may not be necessary to say more than the following, since some people of lesser intelligence may get confused when the explanation is too long.

"The meaning in a nutshell is this: allow your mind to be as it naturally is, and let thoughts dissolve in themselves. This is your innate mind, which is an unidentifiable, self-knowing, natural awareness. Remain one-pointedly in its continuity and do not get distracted.

"During the daily activities between breaks as well, try to keep this kind of mindfulness undistractedly as much as you can.

"It is important to continue training persistently for a couple of days. Otherwise, there may be a danger of this seeing of mind-essence, which you ahve pursued through various means, slipping away."

"The meditator should therefore train in focusing on that for a couple of days.

Pointing Out Innate Thinking

Second, the meditator should now assume the correct posture in front of (the master, and be told the following):

"Let your mind remain in its natural way. When thoughts have subsided, your mind is an intangible, aware emptiness. Be undistracted and look directly into the identity of this naked state!

"At this moment, allow a feisty thought, such as delight, to take form. The very moment it vividly occurs, look directly into its identity from within the state of aware emptiness.

"Now, is this thought the intangible and naked state of aware emptiness? Or is it absolutely no different from the identity of innate mind-essence itself? Look!"

Let the meditator look for a short while.

The meditator may say, "It is the aware emptiness. There seems to be no difference." If so, ask:

"Is it an aware emptiness after the thought has dissolved? Or is it an aware emptiness by driving away the thought from meditation? Or, is the vividness of the thought itself an aware emptiness?"

If the meditator says it is like one of the first two cases, he had not cleared up the former uncertainties and should therefore be set to resolve this for a few days.

On the other hand, if he personally experiences it to be like the latter case, he has seen identity of thought and can therefore be given the following pointing-out instruction:

"When you look into a thought's identity, without having to dissolve the thought and without having to force it out by meditation, the vividness of the thought is itself the indescribable and naked state of aware emptiness. We call this seeing the natural face of innate thought or thought dawns as dharmakaya.

"Previously, when you determined the thought's identity and when you investigated the calm and the moving mind, you found that there was nothing other than this intangible single mind that is a self-knowing, natural awareness. It is just like the analogy of water and waves.

"This being so, is there any difference between calm and movement?

"Is there any difference between thinking and not thinking?

"Is it better to be serenely calm? Do you need to be elated about it?

"Is it worse when a thought abruptly arises? Do you need to be unhappy about it?

"Unless you perceive this hidden deception, you will suffer the meditation famine. So, from now on, when a thought does not arise you need not deliberately make one arise so as to train in the state of its arising, and when the thought does arise you need not deliberately prevent it, so as to train in the state of its nonarising. Thus, do not be biased toward calm or movement.

"The principle for this thought can be applied to all thoughts. However, the meditator should train for a while in simply making use of thoughts, so when no thoughts arise, conjure one up on purpose and sustain its essence. Otherwise, there is a danger of losing sight of the identity of thoughts.

The meditator should, therefore, be instructed to continue practicing diligently for several days. If it is preferably, bring in some quotations to instill certainty.

Pointing Out Innate Perception

Third, the physical posture and so forth should be kept just as before. Then ask:

"While in the composure of the natural state, allow a visual perception, such as that of a mountain or a house, to be vividly experienced. When looking directly at the experience, is this perception itself an intangible aware emptiness? Or, is it the aware and empty nature of mind? Look for a while to see what the difference between them is."

Let the meditator look. He may say, "There is no difference. It is an intangible, aware emptiness." If so, then ask:

"Is it an aware emptiness after the perceived image has disappeared? Or, is the image an aware emptiness by means of cultivating the aware emptiness? Or, is the perceived image itself an aware emptiness?"

If the answer comes that it is one of the first two cases, the meditator has not thoroughly investigated the above and should therefore once more be sent to meditate and resolve this.

If he does experience that the vividly perceived visual image itself -- unidentifiable in any way other than as a mere presence of unconfined perception -- is an aware emptiness, the master should then give this pointing-out instruction:

"When you vividly perceive a mountain or a house, no matter how this perception appears, it does not need to disappear or be stopped. Rather, while this perception is experienced, it is itself an intangible, empty awareness. This is calledseeing the identity of perception."

"Previously you cleared up uncertainties when you looked into the identity of a perception and resolved that perceptions are mind. Accordingly, the perception is not outside and the mind is not inside. It is merely, and nothing other than, this empty and aware mind that appears as a perception. It is exactly like the example of a dream-object and the dreaming mind.

"From the very moment a perception occurs, it is a naturally freed and intangible perceiving emptiness. This perceiving yet intangible and naked state of empty perception is called seeing the natural face of innate perception or perception dawning as dharmakaya.

"This being so, 'empty' isn't something better and 'perceiving' isn't something worse, and perceiving and being empty are not separate entities. So, you can continue training in whatever is experienced. When perceiving, in order to deliberately train in perception, there is no need to arrest it. When empty, in order to deliberately train in emptiness, you do not need to produce it.

"Whenever you recall the mindful presence of practice, all of appearance and existence is the Mahamudra of dharmakaya, without the need to adjust, accept or reject. And so, from now on, continue the training without being biased toward perception or emptiness by repressing or encouraging either of them.

"Nevertheless, for a while allow various kinds of perceptions to take place. While perceiving it is essential to be undistracted from sustaining the unidentifiable essence."

Thus, let the meditator train for several days. If it is preferred, bring in some quotations to instill certainty."

Outside the three realms are shining in freedom

Inside the wisdom, self-arisen, shines

And in between is the confidence of realizing basic being

I’ve got no fear of the true meaning—that’s all I’ve got!

In this verse Milarepa sings about his realization of the true nature of reality. To realize the true nature of reality, the necessary outer condition is for the “three realms” to be “shining in freedom.” The three realms refer to the universe and all of the sentient beings within it. Sentient beings inhabit the desire realm, the form realm, and the formless realm, so these three realms include all the experiences that one could possibly have, and they are shining in freedom—they are self-liberated.*

“Self-liberation” in one sense means that appearances of the three realms do not require an outside liberator to come and set them free, because freedom and purity are their very nature. This is because appearances of the three realms are not real. They are like appearances in dreams. They are the mere coming together of interdependent causes and conditions; they have no essence of their own, no inherent nature. This means that the appearances of the three realms are appearance-emptiness inseparable, and therefore, the three realms are free right where they are. Freedom is their basic reality. However, whether our experience of life in the three realms is one of freedom or bondage depends upon whether we realize their self-liberated true nature or not. It is like dreaming of being imprisoned: If you do not know you are dreaming, you will believe that your captivity is truly existent, and you will long to be liberated from it. But if you know you are dreaming, you will recognize that your captivity is a mere appearance, and that there is really no captivity at all—the captivity is self-liberated. Realizing that feels very good.

The term “self-liberation” is also used in the Mahamudra and Dzogchen teachings, which describe appearances as “self-arisen and self-liberated.” This means that phenomena have no truly existent causes. For example, with a car that appears in a dream, you cannot say in which factory that car was made. Or with the person who appears in the mirror when you stand in front of it, you cannot say where that person was born. Since the dream car and the person in the mirror have no real causes for arising, all we can say about them is that they are self-arisen, and therefore they are also self-liberated.

When we apply this to an experience of suffering, we find that since our suffering has no real causes, it does not truly arise, like suffering in a dream. So it is self-arisen, and therefore it is self-liberated. Since the suffering is not really there in the first place, it is pure and free all by itself. And apart from knowing self-liberation is suffering’s essential nature and resting within that, we do not need to do anything to alleviate it.

Thus, Milarepa sings that what one needs on the inside is to realize self-arisen original wisdom. This wisdom is the basic nature of mind, the basic nature of reality, and all outer appearances are this wisdom’s own energy and play. Original wisdom is self-arisen in the sense that it is not something created; it does not come from causes and conditions; it does not arise anew, because it has been present since beginningless time as the basic nature of what we are. We just have to realize it. The realization of original wisdom, however, transcends there being anything to realize and anyone who realizes something, because original wisdom transcends duality.

How can we gain certainty about and cultivate our experience of this wisdom? Since wisdom is the true nature of mind, begin by looking at your mind. When you look at your mind, you do not see anything. You do not see any shape or color, or anything that you could identify as a “thing.” When you try to locate where your mind is, you cannot find it inside your body, outside your body, nor anywhere in between. So mind is unidentifiable and unfindable. If you then rest in this unfindability, you experience mind’s natural luminous clarity. That is the beginning of the experience of original wisdom. For Milarepa, original wisdom is shining. It is manifesting brightly through his realization of the nature of the three realms and of his own mind.

In the third line, Milarepa sings of his confidence of realizing the true nature of reality, the true meaning. There are the expressions and words that we use to describe things, and the meaning that these words refer to—here Milarepa is singing about the latter. He is certain about the basic nature of reality, and as he sings in the fourth line, he has no fear of it, no doubts about what it is. He is also not afraid of the truth and reality of emptiness. When he sings: “that’s all I’ve got,” he is saying: “I am not somebody great. I do not have a high realization. All I have got is this much.” This is Milarepa’s way of being humble.

One can easily be frightened by teachings on emptiness. It is easy to think: “Everything is empty, so I am all alone in an infinite vacuum of empty space.” If you have that thought, it is a sign that you need to meditate more on the selflessness of the individual. If you think of yourself as something while everything else is nothing, it is easy to get a feeling of being alone in empty space. However, if you remember that all phenomena, including you yourself, are equally of the nature of emptiness, beyond the concepts of “something” and “nothing,” then you will not be lonely; you will be open, spacious, and relaxed.

In the context of this verse, it is helpful to consider a stanza from the Song of Mahamudra by Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thaye:

From mind itself, so difficult to describe,

Samsara and nirvana’s magical variety shines.

Knowing it is self-liberated is view supreme.

“Mind itself,” the true nature of mind, original wisdom, is difficult to describe—it is inexpressible. And from this inexpressible true nature of mind come all the appearances of samsara and nirvana. Appearances do not exist separately from the mind. What appears has no nature of its own. Appearances are merely mind’s own energy; mind’s own radiance; mind’s own light. And so appearances are a magical display. To describe the appearances of samsara and nirvana as a magical variety means that they are not real—they are magic, like a magician’s illusions. Appearances are the magical display of the energy of the inexpressible true nature of mind. When we know this, we know that appearances are self-arisen and self-liberated, and that is the supreme view we can have.

- Most sentient beings, including animals and humans, inhabit the desire realm, so named because desire for physical and mental pleasure and happiness is the overriding mental experience of beings in this realm. The form realm and the formless realm are populated by gods in various meditative states who are very attached to meditative experiences of clarity and the total absence of thoughts, respectively.

A great teaching by Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso on Guru Rinpoche's "Supplication That All Thoughts Be Self-Liberated". which I originally found here http://awakeningtore...label/Mahamudra, the link to the article doesn't work, so here's a working link to the offical website of Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso http://www.ktgrinpoche.org/.

Tashi Delek! I hope that for you everything is filled with auspiciousness, happiness, and excellence. To meet you all here makes me very happy. Gyatrul Rinpoche is a great friend of mine and I have heard a lot about his monastery here. Today, to actually come and be able to see it, to see what a secluded and beautiful place it is, makes me very happy.

I would like to explain to you a supplication that was composed by Guru Rinpoche, a supplication that all thoughts be self-liberated. Guru Rinpoche composed seven chapters of supplications for students to recite to him, and this one comes from a chapter that he taught to the monk whose name was Namkha'i Nyingpo.

Before listening to this teaching, please give rise to the supreme motivation of bodhichitta. When we give rise to bodhichitta, it means that for the benefit of all sentient beings, limitless in number as the sky is vast in its extent, we aim to bring our love and compassion to their ultimate perfection, and to bring our wisdom realizing emptiness to its ultimate perfection. We know that in order to do this we must listen to, reflect upon and meditate on the teachings of the genuine Dharma with all the enthusiasm we can muster in our hearts.

The first verse of the supplication1 is:

All these forms that appear to eyes that see,

All things on the outside and the inside,

The environment and its inhabitants

Appear, but let them rest where no self's found;

Perceiver and perceived when purified

Are the body of the deity, clear emptiness—

To the guru for whom desire frees itself,

To Orgyen Pema Jungnay I supplicate.

What appears to the eyes are forms, which are made up of shapes and colors. Everything that is a shape and color is included in the source of consciousness (Sanskrit: ayatana) that is called form. The shapes and colors that appear to the eyes are found in all of the aspects of the environment in which we live, as well as in all of the sentient beings who inhabit this environment. What is the true nature of the appearances of shapes and colors of the environment and sentient beings? It is that they are dependently arisen mere appearances, which do not exist in essence. The forms that appear do not truly exist. In the abiding nature of reality, their nature is emptiness. They appear while being empty; while empty, they appear. They are appearance-emptiness like rainbows, water-moons, and reflections. All of the objects that appear to the eyes are appearance-emptiness undifferentiable.

As the protector Nagarjuna writes in his Fundamental Wisdom of the Middle Way2:

Like a dream, like an illusion

Like a city of gandharvas,

That's how birth, and that's how living,

That's how dying are taught to be.

The meaning of this verse and the one from Guru Rinpoche's supplication are exactly the same.

This is the actual way forms are. They are appearance-emptiness undifferentiable, but sentient beings do not see this because they think things truly exist, and their thoughts that cling to the true existence of appearances obscure the appearance-emptiness that is their true nature. That is why we practice the Dharma—to cleanse ourselves of this clinging to appearances as truly existent so that we can realize appearances' true nature is appearance-emptiness undifferentiable.

It is like when you dream and you do not know that you are dreaming. The appearances in the dream are appearance-emptiness, but your thought that they truly exist prevents you from seeing that. Even though the dream appearances are appearance-emptiness and have no inherent nature, they seem to be real when you do not know that you are dreaming. You think that they are real and you have experiences that seem to confirm your belief that they are real.

But however much you cling to the appearances in a dream, that does not change what the appearances are from their own side. The essential nature of these appearances is unchanging appearance-emptiness. It never moves from being just that. When you dream and you know you are dreaming, you are free of the thoughts that fixate on the appearances as being truly existent. You are free from that obscuration so you can experience the appearances just as they are: as appearance-emptiness. That enables you to do wonderful things like fly in the sky, move unobstructedly through rock mountains, and travel to pure realms. All that is possible when you recognize a dream for what it is, and in that way, not be blocked by thinking that the appearances truly exist.

In our waking life, even though the environment and sentient beings appear to us, the supplication says "let them rest where no self's found." The environment and sentient beings appear, but let them rest without clinging to them as truly existent. Let them rest in their natural state of appearance-emptiness without fixating on them as being real. When we let the appearances rest without fixating on them as being real, all of the thoughts of there being an actual object out there to perceive and an actual distinct subject perceiving it just dissolve. The thoughts that take the duality of perceived object and perceiving subject to be real dissolve. They are purified.

When that happens, everything shines as luminous emptiness, clarity-emptiness. At this point, you are ready to meditate on the deity, because the deity's enlightened body is also appearance-emptiness. It appears while it is empty; it is empty while it appears—it is like a rainbow. When you meditate on the deity, everything appears as the body of the deity—appearance-emptiness.

When all of the appearances of the physical environment shine as the appearance-emptiness immeasurable palace of the deity, and all the sentient beings in the environment shine as the appearance-emptiness enlightened bodies of the deities themselves, then all desire is free in its own place. It is self-liberated. Thoughts of desire do not come from anywhere and they do not go anywhere. They do not arise, so they do not cease. Since they are free from coming and going, and free from arising and ceasing, thoughts of desire are self-liberated. For this reason the verse says, "To the guru for whom desire frees itself, To Orgyen Pema Jungnay, I supplicate."

The second verse of the supplication is:

All these sounds that appear for ears that hear,

Taken as agreeable or not,

Let them rest in the realm of sound and emptiness

Past all thought, beyond imagination;

Sounds are empty, unarisen and unceasing,

These are what make up the Victor's teaching—

To the teachings of the Victor, sound and emptiness,

To Orgyen Pema Jungnay I supplicate.

What appear to the ears are sounds. What is the nature of this source of consciousness that is sound? In fact, the sounds we hear are like sounds in a dream. Their basic nature is that they are always appearance-emptiness—they appear while being empty, and while being empty they appear.

The two main kinds of sounds we hear are those that we find pleasing and those we do not. Both kinds of sounds, however, are equally appearance-emptiness, sound-emptiness, just as the sounds in a dream are sound-emptiness. If we know this and meditate on the mandala of the deities, then all sounds manifest as the natural sounds of the deity's mantra: sound and emptiness.

From among the eight worldly dharmas,3 four of them are related to sound—sounds that are pleasing, sounds that are displeasing, sounds of praise, and sounds of criticism. We need to give up attachment to the eight worldly dharmas—the four that we like and the four that we do not. To do that, we can see that we need to realize that sounds are sound-emptiness. Then we will not be attached to sounds that are pleasant and sounds of praise, and we will not be averse to sounds of criticism and unpleasant sounds.

In a dream, all sounds of praise and all sounds of criticism, all sounds we like and all sounds we do not, are equally sound-emptiness. They have no inherent nature at all. But when we do not know that we are dreaming, we think these sounds truly exist, and we have experiences of happiness and suffering based on sounds of praise and blame, sounds that we like, and sounds that we do not; all because we do not recognize sounds' basic nature is sound-emptiness. Guru Rinpoche instructs: "Let them rest in the realm of sound and emptiness/Past all thought, beyond imagination." This is an instruction to rest free of clinging to sounds as being truly existent, free of clinging to them as being real. In their basic nature that is sound and emptiness, just let go and relax. Settle into your own basic nature within the nature of sound that is sound and emptiness.

Since the enlightened body of the Buddha is appearance-emptiness, then the sound of the Buddha's speech is also emptiness. It is sound-emptiness undifferentiable. When you know that all sound lacks inherent nature in the same way, then all sound is like the sound of the Buddha's teachings and all sound manifests as the resonance-emptiness sound of the Buddha's speech. The last line of the supplication reads, "To Orgyen Pema Jungnay I supplicate." Here Orgyen Pema Jungnay represents the Buddha's speech that is the sound-emptiness abiding reality of all the sound there is. To this Orgyen Pema Jungnay, we supplicate.

At the beginning of this twenty-first century, everywhere we go there are radios playing, tape recorders playing, the sound of movies and televisions—the world is filled with sound. At this time, then, it is quite important to know that all sounds have no inherent nature. They are sound-emptiness. These days, moment by moment, sounds can be carried across the globe and change so many people's feelings all at once—from happiness to suffering, from suffering to happiness. Just on the basis of hearing a few sounds, millions of people's feelings can change. Also these days it is easy to realize that sounds are sound-emptiness, because if you pick up the phone in America at noon and you call somebody in another country, then for some people it will be midnight, and for some people in other countries it will be morning. So at what time is this sound really being made? In this way, we can easily recognize sound-emptiness. If somebody in America calls someone in India and talks to them on the phone, in America it is noon, in India it is midnight. A daytime mouth is talking to a nighttime ear—at the same time! If sounds were truly existent, that would be impossible. It would be a contradiction for sound made during the day to be heard simultaneously at night. But it is not a contradiction when we know that it is just sound-emptiness. Thinking about things in this way, during these times it is much easier to understand how sound is sound-emptiness.

Also, these days a famous person can give a speech that is broadcast all over the world. The people who like that person will hear that speech as something very pleasant and beautiful. The people who do not like that person will find it repulsive to listen to. The people who have no opinion do not have any reaction to that sound one way or the other. If we ask, "What is that sound, really? Is it good or bad?" again we see that the true nature of sound is inexpressible. These days, sounds beam down from empty space. They come from empty buildings and even empty cars. It is important for us to be able to examine these sounds and their sources to see that they are sound-emptiness, because most of the suffering we experience comes from hearing sounds. We need to train in the understanding of sound as it is taught in the Middle Way, which is that in genuine reality, sounds are empty of any essence. In apparent reality, they are dependently arisen mere appearances.

As the glorious Chandrakirti wrote,

Things do not arise causelessly, nor from Ishvara,

Nor from self, nor other, nor both;

Therefore, it is clear that things arise

Perfectly in dependence upon their causes and conditions.

Things do not arise from any of the four possible extremes: from self, other, both or without cause, and there's no fifth possibility. Therefore, things do not truly arise—they do not come into existence; they do not actually happen. Then what is the appearance of them happening? It is just like the appearance of things happening in a dream; like the appearance of a moon shining on a pool of water; and like the appearance of an illusion. It is dependently arisen mere appearance. In this way, since sounds do not exist in genuine reality, and since in relative reality they are just dependently arisen mere appearances, all sounds are simply sound-emptiness. When you recite mantras, then mantras are also sound-emptiness.

We supplicate Guru Rinpoche at the end of the verse, because even though we know that sounds are sound and emptiness, we are obscured from realizing that directly by our thoughts that cling to sounds as being truly existent. We supplicate for Guru Rinpoche's blessing so that these thoughts that sounds truly exist may dissolve, and when they dissolve, that we will recognize the true nature of sound is sound-emptiness.

The third verse of the supplication is:

All these movements of mind towards its objects,

These thoughts that make five poisons and afflictions,

Leave thinking mind to rest without contrivances,

Do not review the past nor guess the future;

If you let such movement rest in its own place,

It liberates into the dharmakaya—

To the guru for whom awareness frees itself,

To Orgyen Pema Jungnay I supplicate.

For ordinary beings, mind is discursive. It moves. It moves towards objects. It moves towards the three times. It is constantly thinking about one thing or another. Mind is moved by thoughts of the five poisons. When mind encounters an object it likes, it moves towards that object with thoughts of attachment. When mind encounters an object it does not like, it moves towards that object with thoughts of aversion, thoughts of anger. When mind judges something incorrectly, it moves towards that object with bewilderment. When one's mind believes that one has qualities that one does not have, it moves towards oneself with thoughts of arrogance. When mind looks at somebody else and sees things that it does not have, it moves towards that person with thoughts of jealously. In this way, thoughts of the five poisons constantly move the mind. "Leave thinking mind to rest without contrivances." When thoughts of the five poisons are moving the mind, just let mind rest without trying to fix anything, without trying to change anything, without reviewing the past kleshas (disturbing mental states) or wondering what happened to them; and without anticipating what types of disturbing states of mind one might experience in the future. Do not review the past, do not guess the future. Just let mind relax as it is right now.

We do not need to try to prevent thoughts of desire from arising. We do not need to try to stop thoughts of anger or jealously once they have arisen. Do not try to prevent anything; do not try to stop or change anything; just simply do not take any of those movements of mind to be truly existent. That is the instruction because we could not stop the thoughts of the five poisons from arising, even if we wanted to! We could not do that, but we do not have to. All we have to do is recognize that these thoughts lack any essence.

How do we do this? Whatever thought arises, look straight at it with your eye of wisdom and settle into its basic nature. When you do that, all thoughts and all disturbing states of mind are liberated within the dharmakaya. They are self-liberated. The whole collection of thoughts is free just as it is. This is awareness, and this awareness is awareness-emptiness. Since this awareness-emptiness is pure in nature, whatever obscurations there may be have no essence. Awareness itself is self-liberated. It is free just as it is.

Then we supplicate the guru whose awareness is self-liberated. This is Guru Rinpoche. For Guru Rinpoche, awareness frees itself. We supplicate you Orgyen Pema Jungnay for your blessings so that we may realize, as you do, the self-liberation of awareness.

The Lord of Yogis Milarepa sang in his vajra song of realization called "The Three Nails"4:

To describe the nails of meditation, the three

All thoughts in being dharmakaya are free

Awareness is luminous, in its depths is bliss

And resting without contrivance is equipoise

All thoughts are dharmakaya in their nature. Thoughts are free all by themselves, without having to do anything to them, stop them, or change them in any way. They are naturally dharmakaya. What is dharmakaya like? It is luminous. It is awareness. It is bliss. How do we experience this dharmakaya in meditation? Rest without contrivance. Rest without artifice. This is equipoise. This is the experience of dharmakaya. The verses of Milarepa and Guru Rinpoche have the same meaning.

What is awareness-emptiness like? Milarepa described it in the following way in the song "The Ten Things it is Like"5:

When you know the true nature of everything to be known

The wisdom that's aware of the true nature's like a cloud-free sky

With these two lines, Milarepa tells us the emptiness aspect of awareness is like the sky completely free of clouds. Then he sings:

When the mud settles down and mind's river is crystal clear

Self-arisen awareness is like a polished mirror's shine

Milarepa illustrates the luminous, bright, vivid aspect of awareness with the example of a perfectly polished mirror's sparkling shine. In this way, we see what emptiness is like, we see what awareness is like, and then we can understand that the two are undifferentiable.

The great pandit Shakya Chokden described the noble Asanga's explanation of genuine reality as follows:

Clarity-emptiness, mere awareness, empty of the duality of perceived and

perceiver is all phenomena's abiding reality.

Knowing this and combining it with a limitless accumulation of merit, the

spontaneously present three kayas will manifest.

This is Asanga's tradition.

In this way, Asanga presents the true nature of reality of all phenomena as nondual luminous emptiness, nondual awareness-emptiness. The explanation that the true nature of reality is emptiness beyond all concept of what it might be is the presentation of the Middle Way Consequence School (Prasangika Madhyamaka). The presentation of the true nature of reality as awareness-emptiness, luminous clarity, is the presentation of the Shentong Madhyamaka, the Empty of Other Middle Way School, and also the presentation of the Mahamudra and Dzogchen traditions. What does the term "empty of other" or shentong mean? This is described in the text called the Gyu Lama, the Treatise on Buddha Nature:

The element is empty of that which is separable from it, all fleeting stains.

But it is not empty of that which is inseparable from it, its own unsurpassable qualities.

"Empty of other" means that the buddha nature, the true nature of mind, luminous clarity, awareness, is empty of that which is different from it: stains and flaws. It is empty of those. But it is not empty of the spontaneously present qualities, the naturally present qualities of enlightenment. These unsurpassable qualities are totally inseparable from the true nature of mind.

In short, this supplication is a supplication that we will manifest our own basic nature. We supplicate the guru to bless us so that we can manifest the awareness-emptiness that is the true nature of mind. It is a supplication that all appearances will be self-liberated as the enlightened body of the deity, all sounds will be self-liberated as the enlightened speech of the deity, and all thoughts will be self-liberated as essential reality itself.

The last verse of the supplication sums it all up:

Grant your blessing that purifies appearance

Of objects perceived as being outside;

Grant your blessing that liberates perceiving mind,

The mental operation seeming inside;

Grant your blessing that between the two of these

Clear light will come to recognize its own face;

In your compassion, sugatas of all three times,

Please bless me that a mind like mine be freed.

Grant your blessings that all clinging to objects on the outside as truly existent will be self-liberated. Grant your blessings that all thoughts on the inside will be self-liberated. Grant your blessings that in between, luminous clarity, Dzogchen, will recognize its own face. In your compassion, realized buddhas of all three times, grant your blessings that I and all sentient beings may be freed from clinging to characteristics. Grant your blessings that I and all sentient beings may be freed from the bondage of samsara. Grant your blessings that I and all sentient beings may be freed from the bondage of believing that duality truly exists. Grant your blessing that all of our concepts of duality will be self-liberated.

My departing prayer is that Gyatrul Rinpoche be healthy, that he live a long life, and that his activity for the benefit of all sentient beings flourish. And I pray that all of you, his students, bring your activities of listening to, reflecting on and meditating on the teachings of the genuine Dharma to their perfection and that, through this, you are of great benefit to all of the limitless number of sentient beings. And especially here at Tashi Chöling may the teachings of the practice and explanation lineages flourish and bring great benefit to all of the beings of this land.

Translated by Ari Goldfield.

1 The Guru Rinpoche Prayer is translated by Jim Scott.

2 Translated by Jim Scott and Ari Goldfield.

3 The eight worldly dharmas are what worldly beings strive to attain or avoid. The four not explicitly mentioned in this paragraph are happiness, pain, gain, and loss.

4 Translated by Jim Scott.

5 Translated by Jim Scott and Ari Goldfield.

"...The two meditation practices of shamatha and vipashyana each have their place within Mahamudra practice, but they do not have the same objective. Shamatha’s aim is temporary, immediate. When our minds are disturbed or restless, they are not at peace. Cultivating the settled state of shamatha, we find that we are able to be more steady, more tranquil. That is the purpose of shamatha. Shamatha is not sufficient unto itself to attain enlightenment, but it is a support for Mahamudra practice and is therefore imperative.

What then is vipashyana, which literally means “clear seeing,” in the context of Mahamudra? First of all, we have bewildered ourselves into samsara. During this confused state, we do not see clearly the true nature of things, what reality is. The practice of vipashyana develops the ability to see clearly the actual state of affairs, to see the basic condition of what is. Training in vipashyana eliminates negative emotions and clarifies our lack of knowing, our ignorance. It also deepens our insight and wisdom.

Right now, while adrift on samsara’s ocean, we are confused about what is real, about the nature of things. In this state, there are many worries and a lot of fear and uneasiness. To be free of these we need to be free of the bewilderment and confusion. When you are free of confusion, the uneasiness, worry and fear evaporate all by themselves. For example, if there is a rope lying on the ground and someone mistakes it for a poisonous snake, he will be frightened. He worries about the snake and it creates a lot of anxiety. This uneasiness continues until he discovers that it is actually not a snake, but simply a rope. It was merely a mistake. The moment we realize the rope is just a rope, not a snake, our uneasiness, fear and anxiety disappear. In the same way, upon seeing the natural state of what is, all the suffering, fear and confused worries that we are so engrossed in will disappear. The focal point of vipashyana training is seeing what is real.

THE PATHS OF REASONING AND DIRECT PERCEPTION

The pivotal difference between the path of reasoning and the path of direct perception is whether our attention faces out, away from itself, or whether the mind faces itself, looking into itself. The path of reasoning is always concerned with looking at something “out there.” It examines using the power of reason until we are convinced that what we are looking at is by nature empty, devoid of an independent identity. Whether on a coarse or subtle level, it is definitely empty. However, no matter how long and how thoroughly we convince ourselves that things are by nature empty, every time we stub our toe on something it hurts. We are still obstructed; we cannot move our hands straight through things, even though we understand their emptiness. The path of reasoning alone does not dissolve the mental habitual tendency to experience a solid reality that we have developed over beginningless lifetimes.

It is not that a particular practice transforms the five aggregates—forms, sensations, perceptions, formations and consciousnesses—into emptiness. Instead it is a matter of acknowledging how all phenomena are empty by nature. This is how the Buddha taught in the sutras. A person presented with such a teaching may often understand the words and trust the teachings, but personally he does not experience that that is how it really is. Nagarjuna kindly devised the Middle Way techniques of intellectual reasoning in order to help us understand and gain conviction. By analyzing the five aggregates one after the other, one eventually is convinced, “Oh, it really is true! All phenomena actually are empty by nature!”

While we use many tools to reach such an understanding, the reasoning of dependent origination is very simple to understand. For example, when standing on one side of a valley you say that you stand on “this” side, and across the valley is the “other” side. However, if you walk across the valley you will again describe it as “this” side, though it was the “other” side before. In the same way, when comparing a short object to a longer one, we agree that one is shorter and the other longer. Nevertheless, that is not fixed because if you compare the longer one to something even longer, it is then the shorter one. In other words, it is impossible to pin down a reality for such values; they are merely labels or projections created by our own minds.

We superimpose labels onto temporary gatherings of parts, which in themselves are only other labels superimposed on a further gathering of smaller parts. Each thing only seems to be a singular entity. It appears as if we have a body and that there are material things. Yet, just because something appears to be, because something is experienced, does not mean that it truly exists. For example, if you gaze at the ocean when it is calm on a clear night you can see the moon and stars in it. But if you sent out a ship, cast nets and tried to gather up the moon and stars, would you be able to? No, you would find that there is nothing to catch. That is how it is: things are experienced and seem to be, while in reality they have no true existence. This quality of being devoid of true existence is, in a word, emptiness. This is the approach of using reasoning to understand emptiness.

Using reasoning is not the same as seeing the emptiness of things directly and is said to be a longer path. Within the framework of meditation, the intellectual certainty of thinking that all things really are emptiness is not a convenient method of training; it takes a long time. That is why the Prajnaparamita scriptures mention that a Buddha attains true and complete enlightenment after accumulating merit over three incalculable eons. Yet, the Vajrayana teachings declare that in one body and one lifetime you can reach the unified level of a vajra-holder; in other words, you can attain complete enlightenment in this very life. Though they would appear to contradict each other, both statements are true. If one uses reasoning and accumulates merit alone, it does take three incalculable eons to reach true and complete enlightenment. Nevertheless, by having the nature of mind pointed out to you directly and taking the path of direct perception, you can reach the unified level of a vajra-holder within this same body and lifetime.

Taking direct perception as the path, using actual insight, is the way of the mind looking into itself. Instead of looking outward, one turns the attention back upon itself. Often we assume that mind is a powerful and concrete “thing” we walk around with inside. But in reality it is just an empty form. When looking into it directly to see what it is, we do not need to think of it as being empty and infer emptiness through reasoning. It is possible to see the emptiness of this mind directly. Instead of merely thinking of it, we can have a special experience—an extraordinary experience—and discover, “Oh, yes, it really is empty!” It is no longer just a conclusion we postulate. We see it clearly and directly. This is how the great masters of India and Tibet reached accomplishment.

Instead of inferring the emptiness of external phenomena through reasoning, the Mahamudra tradition taught by Tilopa, Naropa, Marpa and Milarepa shows us how to directly experience emptiness as an actuality. Since we habitually perceive external objects as always having concrete existence, we do not directly experience them as being empty of true existence. It is not very practical to become convinced of the emptiness of external objects such as mountains, houses, walls, trees, and so forth. Instead, we should look into our own mind. When we truly see our mind’s nature, we find it has no concrete identity whatsoever. This is the main point of using direct perception: look directly into your own mind, see in actuality that it is empty, and then continue training in that.

This mind, the perceiver, does experience a variety of moods. There are feelings of being happy, sad, exhilarated, depressed, angry, attached, jealous, proud or close-minded; sometimes one feels blissful, sometimes clear or without thoughts. A large variety of different feelings can occupy this mind. However, when we use the instructions and look into what the mind itself really is, it is not very difficult to directly perceive the true nature of mind. Not only is it quite simple to do, but it is extremely beneficial as well.

We usually believe that all of these different moods are provoked by a material cause in the external environment, but this is not so. All of these states are based on the perceiver, the mind itself. Therefore, look into this mind and discover that it is totally devoid of any concrete identity. You will see that the mental states of anger or attachment, all the mental poisons, immediately subside and dissolve—and this is extremely beneficial.

To conclude this section, I will restate my previous point. On the one hand, we hear that to awaken to true and complete enlightenment, it is necessary to perfect the accumulations of merit through three incalculable eons. Then on the other hand, we hear that it is possible to attain the unified level of a vajra-holder within this same body and lifetime. These two statements appear to contradict one another. Truthfully, there is no way one could be enlightened in one lifetime if one had to gather accumulations of merit throughout three incalculable eons. However, if one could be enlightened in a single lifetime then there seems to be no need to perfect the accumulation of merit throughout three incalculable eons. Actually, both are right in that it does take a very long time if one takes the path of reasoning. Whereas it is possible to attain enlightenment within a single lifetime if one follows the tradition of the pith instructions, using direct perception as the path.

ESTABLISHING THE IDENTITY OF MIND AND THE VARIOUS PERCEPTIONS

It should be clear now that our use of the term vipashyana refers to direct perception. To attain this direct perception, we must undertake two tasks: first, gain certainty about the identity of mind; second, gain certainty about the identity of mind’s expression, which includes thought and perceptions. Put another way, we need to investigate three aspects: mind, thought and perception.

The first of these—mind—is when one is not involved in any thoughts, neither blatant thought states nor subtle ones. Its ongoing sense of being present is not interrupted in any way. This quality is called cognizance, or salcha in Tibetan. Salcha means there is a readiness to perceive, a readiness to think, to experience, that does not simply disappear. Since we do not turn to stone or into a corpse when we are not occupied by thinking, there must be an ongoing continuity of mind, an ongoing cognizance.

Next are thoughts, or namtok. There are many different types of thoughts, some subtle, like ideas or assumptions, and others quite strong, like anger or joy. We may think that mind and thoughts are the same, but they are not.

The third one, perceptions, or nangwa, actually has two aspects. One is the perception of so-called external objects through seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting and touch. Let us set those aside for the time being, though, as they are not the basis for the training at this point. The other aspect of perception deals with what occurs to the sixth consciousness: mental images. These mental impressions are not perceived through the senses but somehow occur to the mind in the form of memories, something imagined or thought of. Nevertheless, each of these mental impressions feels as if it is sight, sound, smell, taste or texture. Usually, we do not pay attention to any of this—it just happens and we are caught up in it; for example, when we are daydreaming or fantasizing.

It is important to become clear about what mind, thoughts and perceptions actually are—not in a theoretical way but in actuality. In the past, we may not have paid much attention to mind’s way of being when not occupied with thoughts or perceptions. We may not have looked into what the mind itself—that which experiences or perceives—actually consists of and, therefore, we may not be certain of it. When there are thoughts, mental images or perceptions, the usual habit is simply to lose control and be caught up in the show. We continually get absorbed in what is going on, instead of taking a good, clear look at the perceiving mind. We tend not to be aware that we are thinking or daydreaming; we tend to be in a rather vague, hazy state. Meditation training lets these thoughts and mental images become quite vivid. They can become as clear as day. At this point, we should take a good look and in an experiential way personally establish what their actual nature or identity is.

We use the word examine repeatedly. When you establish the nature of things by means of reason, examining refers to intellectual analysis; but that is not what we are talking about now. Unlike an intellectual investigation, examining should be understood as simply looking at how things actually are.

ESTABLISHING THE IDENTITY OF MIND—THE BASIS

The Mahamudra sense of vipashyana does not mean to examine concepts, but to look into what the mind actually is, namely a sense of being awake and conscious, continuously present and very clear. Whenever we do look, no matter when, we cannot help but discover that mind has no form, color or shape—none at all. Then we may wonder, “Does that mean that there is no mind? Does the mind not exist?” If there were no consciousness in the body, the body would be a corpse. Yet we can see and hear, and we can understand what we are reading—so we are not dead, that’s for sure. The truth is that while mind is empty—it has no shape, color or form—it also has the ability to cognize; it has a knowing quality. The fact is that these two aspects, being empty and able to know, are an indivisible unity.

Mind does exist as a continuing presence of cognizance. We are not suddenly extinct because there are no thoughts; there is something ongoing, a quality of being able to perceive. What exactly is this mind? What does it look like? If mind exists, then in what mode does it exist? Does the mind have a particular form, shape, color and so forth? We should simply take a close look at what it is that perceives and what it looks like, then try to find out exactly what it is.

The second question is, where is this mind, this perceiver, located? Is it inside or outside of the body? If outside, then exactly where? Is it in any particular object? If it is in the body, then exactly where? Does it pervade throughout the body—head, arms, legs, etc.? Or is it in a particular part—the head or torso, the upper part or the lower part? In this way, we investigate until we become clear about the exact shape, location and nature of this perceiving mind. Then if we do not actually find any entity or location, we may conclude that mind is empty. There are different ways in which something can be empty. It could simply be absent, in the sense that there is no mind. However, we have not totally disappeared; we still perceive and there is still some experience taking place, so you cannot say that mind is simply empty. Though this mind is empty it is still able to experience. So what is this emptiness of mind?

By investigating in this way, we do not have to find something that is empty or cognizant or that has a shape, color or location. That is not the point. The point is simply to investigate and see it for what it is—however that might be. Whether we discover that the perceiver is empty, cognizant or devoid of any concreteness, it is fine. We should simply become clear about how it is and be certain—not as a theory, but as an actual experience.

If we look for a perceiver, we won’t find one. We do think, but if we look into the thinker, trying to find that which thinks, we do not find it. Yet, at the same time, we do see and we do think. The reality is that seeing occurs without a seer and thinking without a thinker. This is just how it is; this is the nature of the mind. The Heart Sutra sums this up by saying that “form is emptiness,” because whatever we look at is, by nature, devoid of true existence. At the same time, emptiness is also form, because the form only occurs as emptiness. Emptiness is no other than form and form is no other than emptiness. This may appear to apply only to other things, but when applied to the mind, the perceiver, one can also see that the perceiver is emptiness and emptiness is also the perceiver. Mind is no other than emptiness; emptiness is no other than mind. This is not just a concept; it is our basic state.

The reality of our mind may seem very deep and difficult to understand, but it may also be something very simple and easy because this mind is not somewhere else. It is not somebody else’s mind. It is your own mind. It is right here; therefore, it is something that you can know. When you look into it, you can see that not only is mind empty, it also knows; it is cognizant. All the Buddhist scriptures, their commentaries and the songs of realization by the great siddhas express this as the “indivisible unity of emptiness and cognizance,” or “undivided empty perceiving,” or “unity of empty cognizance.” No matter how it is described, this is how our basic nature really is. It is not our making. It is not the result of practice. It is simply the way it has always been.

The trouble is that for beginningless lifetimes we have been so occupied with other things that we have never really paid any attention to it—otherwise we would have already seen that this is how it is. Now, due to favorable circumstances, you are able to hear the Buddha’s words, read the statements made by sublime beings, and receive a spiritual teacher’s guidance. As you start to investigate how the mind is, when you follow their advice, you can discover how mind really is.

ESTABLISHING THE IDENTITY OF THOUGHTS AND PERCEPTIONS—THE EXPRESSION

Having briefly covered establishing the identity of mind, we will now discuss establishing the identity of thoughts and perceptions, which are the expressions of mind. Though empty of any concrete identity, mind’s unobstructed clarity does manifest as thoughts and perceptions.

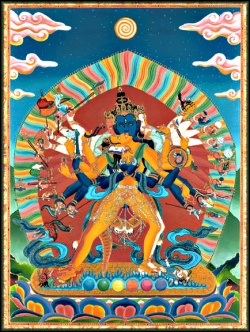

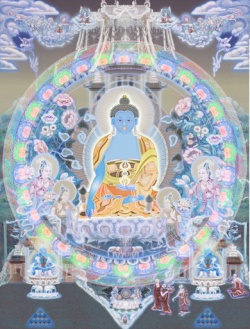

Thoughts can be of many types and, in this context, include emotions. The Abhidharma teachings give a list known as the fifty-one mental events. You may have noticed thangka paintings depicting Vajrayogini wearing a garland of fifty-one freshly cut-off heads to illustrate the need to immediately sever any obvious thoughts that arise. Blatant thoughts include hate, obsessive attachment, compassion and moods such as feeling hazy or very clear. When these arise, either on their own or by us provoking them in order to have something to investigate, we do not need to analyze why we are angry. Instead, immediately upon the arising of a strong thought or emotion, look into where it is, what its identity is and what it is made of. Also, when it arises you should try to find the direction it came from, and when it subsides, where it goes. Whether it is a thought, emotion, feeling or mood, the principle is the same: look into where it comes from, where it abides and where it goes. By investigating in this way, you will find that no real “thing” came from anywhere. Right now the feeling, thought or emotion does not remain anywhere, nor does it actually exist in any concrete way, and, finally, no “thing” actually disappears.

No matter what the thought or emotion may be, we should look into it. But we will fail to find any “thing”—we can’t find where it is, what it looks like or what it is made of.

This failure is neither because we are incapable of looking nor because we have been unsuccessful in finding it, but simply because any movement of the mind is empty of a concrete identity. There is no substance to it, whether it is anger, fear, joy or sorrow—all are merely empty movements of the mind. We discover that looking into thoughts is no different from looking into the quiet mind. The identity of calm mind is empty cognizance and when we look into a thought movement, we also see an empty cognizance. The great masters of the past phrased it like this: “Look into the quiet mind when quiet and look into the moving mind when moving.” We discover that mind and thoughts—thebasis and the expression—have the same identity: empty cognizance.

The same holds true for sensory perceptions and memories. The Buddhist teachings define two aspects of reality: relative truth and ultimate truth. From the relative point of view, we cannot deny that there are mental images and memories, but from the point of view of the ultimate truth, we are forced to admit that they do not exist. This appears to be a contradiction. However, while experientially such images do occur to us, when we investigate what they really are, there is no thing to find, no location for them, and no identity or substance from which they are made.

You might wonder what is the use of understanding that our thoughts and perceptions are all by nature empty of any concrete identity. Sometimes we get so happy. It feels so wonderful and we love it; we cling wholeheartedly to whatever we experience or whatever we think of. At other times it is very painful and we feel like we can’t take it. This is simply due to attaching some solid identity to our thoughts and perceptions. These experiences are not so overwhelming once we clearly see the reality of these thoughts and perceptions—that their identity is not real or concrete. They become much lighter and do not weigh us down so much anymore. That is the immediate benefit. The lasting benefit is that our experience and understanding of the natural state of mind becomes clearer and clearer, more and more stable.

In this method, we do not become clear about what mind, thoughts and mental impressions are by intellectually building a theory of what they must be like and then forcing our experience to agree with our preconceived ideas. Instead, we go about it in an experiential way. We simply allow mind, thoughts or mental perceptions to be whatever they are and then look at them, investigate them. With no need to maintain any set notions about how they must be and forcing them to fit such a description, simply take a close look at the situation as it is. This is neither very complicated nor strenuous, because you are not looking into something other, but rather into this very mind that you already have right here. All you need to do is look at what it actually is. You do not have to imagine any inaccessible thoughts; simply look at your available thoughts and emotions, investigate where they are and what they are made of. The same goes for any mental impressions—simply investigate what they are as they occur. That is the training. Please spend some time giving mind, thoughts and mental impressions a close look and establish some certainty about what they actually are.

Here we have dealt with establishing the identity of mind, thoughts and mental impressions. We could have decided that mind, thoughts and mental impressions are empty, or perhaps not empty. Either way, in the context of Mahamudra training, one should not create any ideas about them. Instead, one should get to know them as they are, without any concepts as handles, by simply looking closely into them. One should not try to infer their nature, but rather see what the nature of mind, thoughts and perceptions actually is through direct experience. When we speak of “establishing their nature” or “cutting through misconceptions about mind, thoughts and perceptions,” therefore, we are referring to attaining clarity or certainty through personal experience. It means to see for ourselves, without any preconceived ideas."

How to Determine the Nature of Mind

What kind of experience arises when we look at mind properly, relying upon the quintessential instructions that have been passed down through the Kagyu lineage? When we investigate, we find that the mind has no shape and no color. All matter has shape and color. So, once we've determined that the mind has no shape and no color, we can determine that the mind is not a material form. Does the mind dwell somewhere? When we look, we see that the mind does not dwell outside the body, inside the body, or somewhere in between these two. It doesn't dwell anywhere because there is nothing to dwell. The mind cannot be identified as any thing. It cannot be said to exist in a certain way, nor can it said to be nonexistent. If it were an existent phenomenon, we would be able to discern the way it exists. If we could identify the mind as something that does not exist, then we would also be able to say precisely how it does not exist. But in fact the mind cannot be identified even in that simple way, nor can the mind be identified as something that takes a certain aspect or expression and then changes into something else. We cannot conclusively identify the mind as the changing expressions or moods of the mind. In this way, the mind is found to be free from all elaboration or complexity.

The Mind's Nature

When we look for the nature of the mind, the distinction between the object that is looked at and the thing that is looking is a false distinction. Nevertheless, when we sit down to practice meditation, it seems that there is something that is looked at and something that is looking. Since we are working with our experience, we investigate the way these seem to be. We settle in the meditative stabilization called shamata and look. Who, or what, is looking? Who is it that does not find anything and knows that not finding is the mind's nature? The looker is the wisdom of discriminating awareness. It is the wisdom of discriminating awareness that look's for the mind's nature. We cannot stop there, however. We have to look for the looker, asking: Where is it? What is it? And so forth. When we have found that the looker does not exist as this or that shape or nature, we have arrived at what is called thoroughly nonconceptual wisdom. At that point, we find the mind to be like space....

Mistakes in Perceiving Mind's Nature

There are three kinds of mistakes that might be made at this point. One of these is to think shamata - the simple peaceful state of mind at rest - is the mind's way of being. When the mind looks at the mind, and the samadhi of shamata arises, we might think we have seen the mind's true nature. But this is a mistake. We have not really seen the luminosity that is the mind's true nature, nor have we gained genuine knowledge and conviction of the mind's lack of inherent existence. A second mistake is to consider the various appearances that arise in meditation to be the mind's actual way of being. Due to the force of latent dispositions and habitual tendencies (Tib. bagchag), various things appear when we sit down to meditate. We might think that we have seen the mind's nature, but this is a mistake, for the same reasons. A third mistake would be to think that different temporary experiences (Tib. nyam) that arise in meditation are the mind's way of being. There are three kinds of such temporary experiences: temporary experiences of luminosity, temporary experiences of nonthought, and temporary experiences of bliss. These experiences, however, are merely superficial. They are not actually the mind's way of being because we have not truly recognized the mind's lack of inherent existence. We have not ascertained the mind's lack of inherent existence with sufficient certainty to have great conviction about it. It is extremely important to have this certainty and conviction.

Realizing the Nature of Appearances

We may not be able to realize the nature of external appearances right off; however we can look at the mind and experience its emptiness directly. When we do this, we can by extension understand the nature of apparently external appearances as well. Why is this? It is because the nature of the mind and the nature of appearances are identical. The nature of the mind is the same as the nature of all phenomena. Saraha said, "Since the mind alone is the seed of all, it is this that unfolds samsara and nirvana." This means that all phenomena of samsara and all the phenomena of nirvana arise from the mind. For that reason, when we realize the mind's nature, we will naturally understand the nature of all that appears. Thoughts and appearances are merely expressions of the mind. Their nature is the same as the mind's nature. We might then think that it's not necessary to pursue any further techniques for understanding the nature of thought and appearances. We must follow certain stages of meditation to arrive at the realization. The way we do this is quite similar to the way we understand the selflessness of phenomena as taught in the sutras. Because it is easier to investigate the nature of thoughts than the nature of appearances, we start with investigating the nature of thought....Once we realize that the nature of individual thought, the nature of the mind, and the nature of dharmata are all the same, we then turn to appearances of visible forms, sounds, smells, tastes, and so forth and determine what their nature is. These appearances seem to be things having particular shapes and colors. For instance, the mind begins to appear as mountains, houses, and rivers. From the point of view of mahamudra, we say that these appearances arise through the force of latent predispositions....In the tradition of practicing the quintessential instructions we do not look at and analyze external objects; rather, we look at the mind that apprehends these appearances, analyzing and determining the nature of that mind. We recognize the emptiness that is the nature of that mind. We understand too that emptiness is the nature of the object apprehended by that mind. When a visual form with color and shape appears to an eye consciousness, rather than analyzing that form, we look at the mind seeing it. We ask: What is the mind to which form appears? Does it have a color or a shape? What sort of thing is it? We discover that the seeing mind cannot be found. We then realize that if the seeing mind does not exist, the external object does not exist either. This method also applies with sounds, smells, and so forth....We investigate the mind that experiences pleasure or pain in the same way....

Eliminating Doubts about the Root of Samsara and Nirvana

It is helpful if we know how to meditate on the nature of the mind itself, but if we have not learned to recognize the luminosity-emptiness that is the nature of thought and appearance, then thoughts and appearances will seem to be obstacles to our practice of meditation. As long as we can focus upon the mind itself, we will be able to meditate smoothly. But if we haven't learned how to meditate with the appearances that dawn from any of the consciousnesses or with thoughts and emotions that arise, the process will be rough, difficult, and tumultuous when we have to work with them. There will be internal conflict. That is why it is extremely beneficial to meditate on the nature of thought and appearance and discover that it is luminosity-emptiness.

Eliminating Doubts About Vipashyana

...Vipashyana is not the creation of something new and sensational, nor it is the finding of something that was hidden. Rather, it is a matter of understanding what our mind has always been, naturally, from the beginning. The only problem we have is that we've never looked directly at our mind and therefore haven't experienced our mind as it is....

Question: You were speaking about looking at the looker . When I look into the face of the looker, it ceases, and then a cognizance of looking arises. Is that cognizance another looker, or is it "prajna" or "discriminating intelligence?"

Rinpoche: What does it mean to talk of prajna or the intelligence of discriminating wisdom? Calling it prajna or intelligence is to say that it is not stupid, not obscure, not dull, and not deluded. It understands things as they are. When it sees something, it sees accurately. It knows that certain things are of good quality, poor quality, or whatever. Think about it this way: if we take two sticks and rub it them together, eventually that creates fire, which then burns up the two sticks. In a similar way, if we look at mind, we see that mind is an emptiness that is unidentifiable as anything at all, and then we experience the union of luminosity and emptiness. That prajna, that intelligence of discriminating awareness, experiences and knows the union of luminosity and emptiness that pervades all of the mind and of all one's experience. Because it knows this, the prajna itself does not become solidified. We don't hang onto it. We don't experience it as some kind of real thing that we can fixate on.

Summary of Looking At The Mind When Thoughts Arise

These nine ways of looking at thought make up the technique of viewing the mind within occurrence. This technique, viewing the mind within occurrence, is very important because we begin our practice with shamatha. Through the practice of shamatha we develop a relationship with our thoughts that has some preference and attachment to it. Because we a re attempting to develop a state of non-distraction, then we develop an attitude that is pleased when the mind is still, and disappointed or unhappy when thoughts arise. We become attached to stillness, and we become averse to occurrence. We often get to the point where we view thoughts as enemies or obstructors and view stillness as a friend and as a boon. There is nothing really wrong in that attitude in the context of shamatha practice, because indeed one is attempting to develop a state of tranquility; but it eventually has to be transcended, and it is transcended by this technique, where you come to view the dharmata, the nature of things, which is itself ultimate peace and tranquility, within thoughts, because this is the nature of thoughts as well.

The Lineage Prayer