A Short Biography of Tsongkhapa

Click here to see other articles relating to word A Short Biography of Tsongkhapa

A Short Biography of Tsongkhapa

Alexander Berzin, August 2003

partly based on a discourse by Geshe Ngawang Dhargyey

Dharamsala, India

The biography of a great lama is called a "namtar" (rnam-thar), a liberating biography, since it inspires the listeners to follow the example of the lama and achieve liberation and enlightenment.

The biography of Tsongkhapa (rJe Tsong-kha-pa Blo-bzang grags-pa) (1357-1419) is indeed inspiring.

Prophesies and Childhood

Both Buddha Shakyamuni and Guru Rinpoche prophesied Tsongkhapa’s birth and attainments. At the time of Buddha Shakyamuni, a young boy who was a previous incarnation of Tsongkhapa presented a crystal rosary to Buddha and received a conch shell in return.

Buddha prophesied Manjushri would be born as a boy in Tibet, would found Ganden monastery, and would present a crown to my statue. Buddha gave the boy the future name Sumati-kirti (Blo-bzang grags-pa, Lozang-dragpa).

Guru Rinpoche also prophesied a monk named Lozang-dragpa would be born near China, would be regarded as an emanation of a great bodhisattva, and would make a Buddha-statue into a Sambhogakaya representation.

Several indications before Tsongkhapa’s birth also indicated that he would be a great being.

His parents, for example, had many auspicious dreams that their child would be an emanation of Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri, and Vajrapani.

His future teacher, Chojey Dondrub-rinchen ([[Chos-rje Don-grub rin-chen]), was told by Yamantaka in a vision that he (Yamantaka) would come to Amdo (A-mdo, northeastern Tibet) in a certain year and become his disciple.

Tsongkhapa was born in Tsongkha (Tsong-kha), Amdo, in 1357, the fourth of six sons.

The day after Tsongkhapa’s birth, Chojey Dondrub-rinchen sent his main disciple to the parents with gifts, a statue, and a letter. A sandalwood tree grew from the spot where his umbilical cord fell to the ground.

Each leaf had a natural picture of the Buddha Sinhanada (Sangs-rgyas Seng-ge sgra), and was thus called Kumbum (sKu-‘bum), a hundred thousand body images.

The Gelug monastery called Kumbum was later built on that spot.

See: A Brief History of Kumbum Monastery.

Tsongkhapa was not like an ordinary child. He never misbehaved; he instinctively engaged in bodhisattva type actions; and he was extremely intelligent and always wanted to learn everything.

At the age of three, he took lay vows from the Fourth Karmapa, Rolpay-dorjey (Kar-ma-pa Rol-pa’i rdo-rje) (1340-1383).

Soon after, his father invited Chojey Dondrub-rinchen to their home. The lama offered to care for the education of the boy and the father happily agreed.

The boy stayed at home until he was seven, studying with Chojey Dondrub-rinchen. Just seeing the lama read, he instinctively knew how to read without needing to be taught.

During this time, Chojey Dondrub-rinchen gave the boy the empowerments of Five-Deity Chakrasamvara (Dril-bu lha-lnga), Hevajra, Yamantaka, and Vajrapani.

By the age of seven, he had already memorized their complete rituals, had completed the Chakrasamvara retreat, was already doing the self-initiation, and already had a vision of Vajrapani. He frequently dreamt of Atisha (Jo-bo rJe dPal-ldan A-ti-sha) (982-1054), which was a sign that he would correct misunderstandings of the Dharma in Tibet and restore its purity, combining sutra and tantra, as Atisha had done.

At the age of seven, Tsongkhapa received novice vows from Chojey Dondrub-rinchen and the ordination name Lozang-dragpa. He continued to study in Amdo with this lama until he was sixteen, at which time he went to U-tsang (dBus-gtsang, Central Tibet) to study further.

He never returned to his homeland. Chojey Dondrub-rinchen remained in Amdo, where he founded Jakyung Monastery (Bya-khyung dGon-pa) to the south of Kumbum.

Early Studies in Central Tibet

In Central Tibet, Tsongkhapa first studied at a Drigung Kagyu monastery, where he learned the Drigung mahamudra tradition called "possessing five" (phyag-chen lnga-ldan), medicine, and further details about bodhichitta.

By seventeen, he was a skilled doctor. He then studied Filigree of Realizations (mNgon-rtogs-rgyan, Skt. Abhisamayalamkara), the other texts of Maitreya, and prajnaparamita (phar-phyin, far-reaching discriminating awareness) at several Nyingma, Kagyu, Kadam, and Sakya monasteries, memorizing the texts in just days. By nineteen, he was already acknowledged as a great scholar.

He continued to travel to the most famous monasteries of the Tibetan Buddhist traditions, studying the five major Geshe-training topics and the Indian tenet systems, debating them and sitting for debate examinations.

He received the Kadam lam-rim (lam-rim, graded sutra path) teachings and also innumerable tantric empowerments and teachings, including the Sakya tradition of lamdray (lam-‘bras, the paths and the result), the Drigung Kagyu tradition of the six teachings of Naropa (Na-ro’i chos-drug, six yogas of Naropa), and Kalachakra.

He also studied poetic composition, astrology, and mandala construction. In all his studies, he only had to hear an explanation once and then he understood and remembered it perfectly – as was the case with His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama.

Tsongkhapa always had strong renunciation. He lived extremely humbly and kept his vows purely.

He easily achieved shamatha (zhi-gnas, a stilled and settled state of mind) and vipashyana (lhag-mthong, an exceptionally perceptive state of mind), but was never satisfied with his learning or level of realization.

He continued to travel and requested teachings over and again even on the same texts.

He debated and sat exams with most of the learned masters of his day. One of his main teachers was Rendawa (Red-mda’-ba gZhon-nu blo-gros) (1349-1412), a Sakya master.

Tsongkhapa wrote the Migtsema (dMigs-brtse-ma) praise to him, but this master rededicated it to Tsongkhapa. It later became the verse repeated for Tsongkhapa guru-yoga.

[See: Hundreds of Deities of Tushita (Ganden Lhagyama).

Tsongkhapa began to teach while in his 20s, with his first teaching being on abhidharma (mdzod, special topics of knowledge). Everyone was astounded at his erudition. He also began to write and do more retreats. Soon, he had many disciples of his own. Although some accounts say Tsongkhapa took full monk vows at age 21, it is uncertain in which year this actually took place. It was probably later in his 20s.

]

At one point, he studied and analyzed the entire Kangyur (bKa’-‘gyur) and Tengyur (bsTan-‘gyur) – the translated direct teachings of Buddha and their Indian commentaries.

After that, at age 32, he wrote A Golden Rosary of Excellent Explanations (Legs-bshad gser-phreng), a commentary on Filigree of Realizations and thus on prajnaparamita.

He synthesized and discussed all twenty-one Indian commentaries.

Whatever he wrote, he substantiated with quotes from the entire span of Indian and Tibetan Buddhist literature, comparing and critically editing even different translations.

Unlike previous scholars, he never shied away from explaining the most difficult and obscure passages in any text.

Normally, Tsongkhapa could memorize each day seventeen double-side Tibetan pages of nine lines on each side. Once some scholars held a memorizing contest to see who could memorize the most pages before the sun hit the banner on the roof of the monastery. Tsongkhapa won with four pages, which he recited fluently with no mistakes. The next closest could only do two and a half, and with staggering.

Tsongkhapa soon began to give tantric empowerments and teachings, and especially the subsequent permission (rjes-snang, jenang) of Sarasvati (dByangs-can-ma) for wisdom. He also continued his study of tantra, especially Kalachakra.

One great lama was famous for teaching eleven texts at the same time. A disciple requested Tsongkhapa to do the same.

Tsongkhapa taught instead seventeen major sutra texts, all from memory, one session on each every day, starting them all on the same day and finishing them all three months later, also on the same day.

During the discourse, he refuted incorrect interpretations of each and established his own view. Each day during the discourse, he also did the self-initiation (bdag-‘jug) of Yamantaka and all his other tantric practices.

If we look at his life of only 62 years, and consider how much he studied, practiced (including making tsatsa clay statues), how much he wrote, taught, and did retreats, it would seem impossible that anyone could do even one of them in a lifetime.

Intensive Tantra Study and Practice

Soon after this, Tsongkhapa did his first major tantric retreat, on Chakrasamvara according to the Kagyu lineage. During this retreat, he meditated intensely on the six teachings of Naropa and the six teachings of Niguma (Ni-gu’i chos-drug, six yogas of Niguma). He gained great realization.

After this, at the age of 34, Tsongkhapa decided to engage in intensive study and practice of all four tantra classes. As he later wrote, one cannot truly appreciate the profundity of anuttarayoga tantra unless one has practiced and understood deeply the three lower tantras. Thus, he traveled widely again and received many empowerments and teachings on the three lower tantra classes.

He also studied further the five-stage complete stage (rdzogs-rim) of Guhyasamaja and Kalachakra.

Study and Retreats for Gaining Nonconceptual Cognition of Voidness

Tsongkhapa also went to study the practices of the Manjushri Tantric Cycle and Madhyamaka with the Karma Kagyu Lama Umapa (Bla-ma dbu-ma-pa dPa’-bo rdo-rje).

This great master had studied Madhyamaka with the Sakya tradition and, since childhood, had daily visions of Manjushri, who taught him one verse each day. Tsongkhapa and he became mutual teacher and disciple.

Lama Umapa checked with Tsongkhapa to get confirmation that the teachings he received in his visions of Manjushri were correct. This is very important, since visions can be influenced by demons.

Together with Lama Umapa, Tsongkhapa did an extensive retreat on Manjushri. From this time onward, Tsongkhapa received direct instruction from Manjushri in pure visions and was able to receive from him answers to all his questions. Before this, he had to ask his questions to Manjushri through Lama Umapa.

During the retreat, Tsongkhapa felt he still did not have a proper understanding of Madhyamaka and Guhyasamaja.

Manjushri advised that he do a very long retreat and then would understand the notes he had taken from his instructions. Thus, after teaching a short while, Tsongkhapa entered a four-year retreat with eight close disciples at Olka Cholung (‘Ol-kha chos-lung).

They did thirty-five sets of 100,000 prostrations, one each to the thirty-five confession Buddhas, and eighteen sets of 100,000 mandala offerings, with many Yamantaka self-initiations and study of The Avatamsaka Sutra (mDo phal-cher) for bodhisattva deeds.

They had a vision of Maitreya afterwards.

After the retreat, Tsongkhapa and his disciples restored a great Maitreya statue in Lhasa, which was the first of his four major deeds. They then went into retreat for five more months.

After this, the Nyingma Lama Lhodrag Namka-gyeltsen (Lho-brag Nam-mkha’ rgyal-mtshan), who continually had visions of Vajrapani, invited Tsongkhapa, and they also became mutual teacher and disciple.

He transmitted to him the Kadam lam-rim and oral guideline lineages.

Tsongkhapa wanted to go to India to study more, but Vajrapani advised to stay in Tibet since he would be of more benefit there. Thus, he stayed.

He resolved that later he would write A Grand Presentation of the Graded Stages of the Path (Lam-rim chen-mo) on the graded sutra path and then A Grand Presentation of the Graded Stages of the Tantra Path (sNgags-rim chen-mo) on the stages of practice of the four tantra classes.

Tsongkhapa then did an extensive retreat on the Kalachakra complete stage, and after that, a one-year retreat on Madhyamaka.

Although Tsongkhapa had learned much about Madhyamaka and voidness from his teachers, he had never felt satisfied with the level of explanation.

Before entering this one-year retreat, Manjushri advised him to rely on the Madhyamaka commentary by Buddhapalita (Sangs-rgyas bskyangs). Tsongkhapa did so and, consequently during the retreat, gained full nonconceptual cognition of voidness.

Based on his realization, Tsongkhapa revised completely the understanding of the Prasangika-Madhyamaka teachings on voidness and related topics that the teachers and learned masters of his day had held. In this regard, he was a radical reformer with the courage to go beyond current beliefs when he found them inadequate.

[See: Special Features of the Gelug Tradition.]

Tsongkhapa always based his reforms strictly on logic and scriptural references. When he established his own view as the deepest meaning of the great Indian texts, he was not committing a breach of his close bond and relationship with his teachers. Seeing our spiritual teachers as Buddhas does not mean that we can not go beyond them in our realizations. Tsenzhab Serkong Rinpoche II explained this with the following example.

To make a cake, we need to put together many ingredients – flour, butter, milk, eggs, and so on. Our teachers show us how to make a cake and bake a few for us. They may be very delicious and we may enjoy them greatly.

Due to our teachers’ kindness, we now know how to make a cake.

This does not mean that we cannot make some changes, add some different ingredients, and bake cakes that are even more delicious than those our teachers made. In doing so, we are not being disrespectful toward our teachers.

If the teachers are really qualified, they will rejoice in our improvement on the recipe and enjoy the new cakes with us.

Further Great Deeds

After teaching more, Tsongkhapa again went into retreat, this time with his teacher Rendawa, and wrote most of Lam-rim chen-mo.

During the retreat, he had a vision of Atisha and the lam-rim lineage masters that lasted for a month, clarifying many questions. Next, he studied the six practices of Naropa and mahamudra further with Drigung Kagyu.

During the rainy season after this, he taught vinaya (‘dul-ba, monastic rules of discipline) so clearly, it is regarded as his second great deed.

After he finished Lam-rim chen-mo, Tsongkhapa decided to teach more fully on tantra. First, however, he wrote extensive commentaries on the bodhisattva vows and Fifty Stanzas on the Guru (Bla-ma lnga-bcu-pa, Skt. Gurupanchashika) to emphasize them as the foundation for tantra practice.

Then, while continuing to teach, he wrote Ngag-rim chen-mo and many commentaries on Guhyasamaja. He also wrote on Yamantaka and on Nagarjuna’s Madhyamaka texts.

The Chinese Emperor invited him to become his imperial tutor, but Tsongkhapa excused himself saying he was too old and wanted to stay in retreat.

Over the next two years, Tsongkhapa taught lam-rim and tantra extensively and wrote The Essence of Excellent Explanation of Interpretable and Definitive Meanings (Drang-nges legs-bshad snying-po) on the definitive and interpretable meanings of the Mahayana tenets.

Then, in 1409, at the age of 52, he inaugurated the Monlam Great Prayer Festival (sMon-lam chen-mo) at the Lhasa Jokang (Jo-khang).

He offered a gold crown to the Shakyamuni statue, signifying that it was now a Sambhogakaya statue, not just Nirmanakaya. Sambhogakaya forms of Buddhas live until all beings are liberated from samsara, whereas Nirmanakaya forms live only a short time.

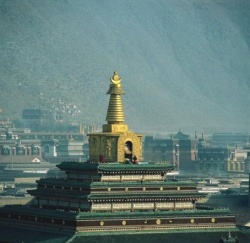

This is considered his third great deed. After this, his disciples asked him to stop traveling so much and they founded Ganden Monastery (dGa’-ldan dGon-pa) for him.

[See: A Brief History of Ganden Monastery.]

At Ganden, Tsongkhapa continued to teach, write (especially on Chakrasamvara), and do retreats.

He commissioned the building of the great Ganden hall with a huge Buddha statue and copper three-dimensional mandalas of Guhyasamaja, Chakrasamvara, and Yamantaka. This is considered his fourth great deed.

He continued his writing and in the end, his collected works totaled eighteen volumes, with the largest amount being on Guhyasamaja.

Passing Away

Tsongkhapa died at Ganden in 1419, at the age of 62. He attained enlightenment after his death by achieving an illusory body (sgyu-lus) instead of bardo. This was to emphasize the need for monks to follow strict celibacy, since enlightenment in this lifetime requires practice with a consort at least once.

Before he passed away, Tsongkhapa gave his hat and robe to Gyeltsabjey (rGyal-tshab rJe Dar-ma rin-chen) (1364-1432), who held the Ganden throne for twelve years afterwards.

This began the tradition of the Ganden Throne Holder (dGa’-ldan khri-pa, Ganden Tripa) being the head of the Gelug order.

The next throne holder was Kaydrubjey (mKhas-grub rJe dGe-legs dpal-bzang) (1385-1438), who later had five visions of Tsongkhapa, clarifying his doubts and answering his questions.

The Gelug lineage has flourished ever since.

Several of Tsongkhapa’s close disciples founded monasteries to continue his lineages and spread his teachings.

While Tsongkhapa was still alive, Jamyang Chojey (‘Jam-dbyangs Chos-rje bKra-shis dpal-ldan)

(1379-1449) founded Drepung Monastery (‘Bras-spungs dGon-pa)

in 1416 and Jamchen Chojey (Byams-chen Chos-rje Shakya ye-shes)

(1354-1435) founded Sera Monastery (Se-ra dGon-pa) in 1419.

After Tsongkhapa’s passing away, Gyu Sherab-senggey (rGyud Shes-rab seng-ge) (1383-1445) founded Gyumay Lower Tantric College (rGyud-smad Grva-tshang)

in 1433 and Gyelwa Gendun-drub (rGyal-ba Ge-’dun grub) (1391-1474), posthumously named the First Dalai Lama, founded Tashilhunpo Monastery (bKra-shis lhun-po) in 1447.