Repentance before the 88 Buddhas

Posted by Bhikshu Kongmu in Chinese Buddhism, Chinese Buddhist Liturgy

Of the many beautiful things that have yet to be fully transplanted from the East into the fertile soil of Western Buddhism is a broad appreciation of the role and practice of repentance. There are many reasons for this, not least of which is that the purpose of repentance is a bit different in Buddhism than it is in western Christianity, where it is often represented as atoning for some that is truly un-atonable: someone else’s mistake (“original” sin). Therefore, it took the death of God’s son to bring humankind back into communion, as we are incapable of doing it ourselves. (However, in Orthodox Christianity, it is a bit different, as I will quote in a moment.)

Buddhism, I hope, is obviously quite different from the general Western understanding of repentance. Rather than confessing our inherent failings, repentance in Buddhism is acknowledging our freedom and our ability to move through and beyond our mistakes in an honest appraisal of our lives. It is showing ourselves that we are able (and willing) to change, and are not bound by our actions that create suffering. Repentance is the willingness to let go of our suffering and step towards true freedom. More than anything else, repentance is, in short, movement.

Buddhism teaches that our suffering (which is the inability to make ourselves happy, try as we might) comes from ignorance about how things really are. This ignorance manifests in three primary ways: greed, anger, and delusion (or confusion.) Our actions based upon any of these three manifestations inevitably create suffering for ourselves and/or others, because they are counter to how the world truly is, in that they assume existence for something that truly has no existence. So, the suffering we experience, in fairly simplistic terms, stems from a misunderstanding of our world. Therefore, repentance is largely the willingness to say, “I know I do not see things clearly; and I wish to perceive things better.”

Repentance is central to the spiritual progress, development, and maturity of all practitioners because it is the acknowledgement of the creation of suffering, and the vowing to refrain from such acts in the future. Or at least, trying to refrain from such acts. Many Buddhists, myself included, make this part of our daily rituals.

Here is the most common repentance verse in Chinese, with one English rendering:

往昔所造諸惡業:All the unwholesome karma created by me,

皆由無始貪瞋癡:Arising from beginningless greed, hatred and delusion;

從身語意之所生:Expressed through my body, speech, and mind;

一切我今皆懺悔:I hereby regret and repent them all.

Here is that quote about how repentance is seen in the Eastern Orthodox Christian Church, which I find very interesting (found here):

One repents not because one is or isn’t virtuous, but because human nature can change. Repentance (Greek: μετάνοια, metanoia, “changing one’s mind”) isn’t remorse, justification, or punishment, but a continual enactment of one’s freedom, deriving from renewed choice and leading to restoration (the return to man’s original state).

I would add that there is, often, an aspect of remorse in sincere repentance, but that is often overshadowed by a deep willingness to move more towards one’s spiritual goal: resolve generally trumps emotion. Regardless, the Eastern Orthodox view of repentance is quite similar to Buddhism’s teaching, as you may see. In fact, there is much about Orthodoxy that is familiar to a Buddhist (but that is a potential topic for another post.)

Repentance is a word that features heavily and prominently in Chinese Buddhism, especially in liturgical settings. In Chinese it is 懺悔 (chàn huǐ), which simply means to repent and regret one’s mistakes. Many, if not most, liturgical services have a repentance verse (or verses) that is recited at least once, and there are specific ceremonies devoted to the cultivation of a repentant mind (including the Great Compassion Repentance ceremony I mentioned here).

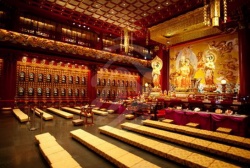

One such beautiful repentance ceremony is called 八十八佛大懺悔文 (bā shí bā dà chàn huǐ wén), or the Great 88 Buddhas Repentance Ceremony. In many Chinese monasteries, Dharma Drum included, this is performed every-other evening as part of the Evening Service. It is one of my favorites, if I’m allowed to say that.

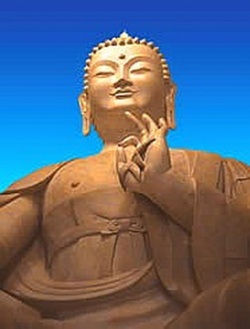

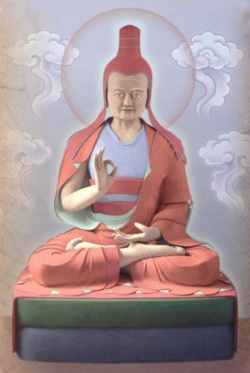

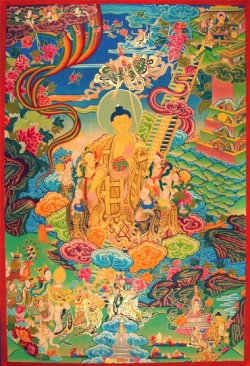

I do not have a sophisticated understanding about this ceremony, but it largely consists of the recitation of the names of 88 different Buddhas as a form of repentance and request for help. Here is a site with iconographic representations of all of the Buddhas. There is also long verse of profound vows at the end as well, which is I believe a quote by Samantabhadra Bodhisattva, as it appears in the Avatamsaka Sutra. But I’m not too certain. (For any reading this who are familiar with Shasta Abbey’s liturgy, this is basically the Vigil Ceremony often done the evening before a festival for one of the major Bodhisattvas.)

Here is an audio file and a .pdf transcript for anyone interested in listening to it (it is about 17 minutes long):

Audio file of 88 Buddha’s Ceremony (this is not from Dharma Drum)

.PDF transcript, with Chinese and English (compiled and translated by Ven. Hui-feng.)

For those interested, you can read a bit more about repentance in Buddhism from Master Yin-Shun here, if you scroll down a bit.

To end, with, here are two passages from the Sutra on the Meditation of Samantabadhra, also known as the Repentance Sutra. These two passages (taken from this edition, very slightly adapted) have always struck me as very profound and beautiful. This sutra is generally considered the “closing” sutra to the Lotus Sutra, towards which I have a strong and enduring affinity. Here are the quotes:

If you contemplate your mind, you will find no mind, except the mind that comes from mis-conceptions. The mind with such conceptions arises from delusion. Like the wind in the sky, it has no grounding. Such a character of things neither appears nor disappears. What is sin? What is virtue? As the thought of self is itself empty, neither sin nor virtue is our master. In this way, all things are neither permanent nor destroyed. If one repents like this, meditating on one’s mind, one finds no mind. Things also do not dwell in things. All things are liberated, show the truth of extinction, and are calm and tranquil. Such a thing is called great repentance, sublime repentance, repentance without sin, the destruction of the self-referential mind. People who practice this repentance are pure in body and mind, like flowing water, not attached to things.

——————–

The whole ocean of hindrances from past actions

arises from illusion.

If you want to repent, you should sit upright

and reflect on the true nature of things.

All evils are like frost and dew.

The sun of wisdom can dissipate them.

As always, I hope you are well.

Thank you for reading.

Lynn McDougal said:

October 9, 2011 at 11:48 pm

Hi Ven. Kongmu! Thank you for this lovely and reflective post. I have only really understood the meaning and necessity of the act of purification and, now that I have worked with it in a different way than in the past the value, compassion and beauty of it is unfolding for me with each recitation. In our tradition, Vajrayana, we do a purification practice once in the morning and once in the evening every day. It is done to the 35 Buddhas (and don’t ask why not 88…who knows about all these numbers!) There is also a very, very special extra purification practice that one can do daily or when one is moved to do so and that regards the diety Vajrasattva. This is (if I may say so) one of my favorites.

The way it was explained to me that made the most sense to my mind was that the act of regret is not a thing one beats oneself up with…it is not guilt! It is, instead, the feeling you would get if you were very, very thirsty and you came upon a table with a glass of liquid in it and you were so driven by your thirst that you just picked up the glass and drank it down immediately…only to discover in the next instant that you had just drunk a glass of poison. The feeling that would be generated in the moment of clear knowing of what you had done is the true feeling here. Basically, “what have I done? I wish I hadn’t done that! I wish I had taken more time to examine things, and explore what that was before just drinking it!” That kind of feeling. You just regret it, realize that there will be after effects that will need to be dealt with, and vow to not repeat that action in the future.

Be well, friend! With joy in the Dharma….Lynn

Reply

Ven. Kongmu said:

October 11, 2011 at 7:54 pm

Dear Lynn,

It is great to read your comments here on this blog. Thank you for sharing, and for taking the time.

I appreciate your thoughts and perspectives on repentance, especially the analogy to drinking poison by mistake; very apt, very helpful.

I’ve also read an analogy by Ven. Yin-shun who compares repentance to opening a jar of poison or stinky-stuff to the fresh air so it can be cleared. As long as we keep it bottled up, it just stays around.

To be honest, I almost didn’t write about this topic this week, as I knew I could only scratch the surface (my time is so crunched these days). Repentance is such a rich, wonderful, and uncomfortable area for contemplation and practice; which makes it worth talking about, but in careful ways.

I consider the repentant mind to the fuel for cultivation/practice. For, with out it, we go nowhere. Repentance is more than, “I could be wrong” (sound familiar?), but it begins with seeing when we are wrong, then striving to do better. And yet, that is really just the beginning. Until we see clearly all the time, there is always a reason to practice repentance.

I have to get back to studying, but wanted to say “thank you” for this and your comment the other week about the Pure Land.

I, too, hope you are well.

–Kongmu

P.S. I also read somewhere recently that for some reason in China, they (whoever “they” are) at some point added 53 Buddhas to the 35 you mention, which is why we have the 88 Buddhas. But, there’s more to the story than I am familiar with.

Reply

virginia said:

March 10, 2012 at 5:12 am

Thank you so very much for a lucid explanation of a Buddhist concept. It was delightful to read a well written blog and I had the opportunity to come across two such blogs back to back this morning. I’ve been dabbling on the subject of Buddhism for many years and still find myself struggling to understand the most basic of anything within the teaching. When it comes to mantras, they are not particularly easy to understand, be it Sankrit or Chinese. Both are difficult to read. But I think Sankrit version is easier to memorize.

Your venerable, am I wrong to think that Buddhists pray before they eat too? Of course we thank God for the food we eat (as well as those who made it happened), and we could go right on eating after we prayed. Shouldn’t we pray for the food being eaten too? Are there prayers we could offer to the beings we use as food to sustain our lives? Is it the Rebirth to Pure Land Dharani? Would you enlighten all of us? Thank you.

Reply

Ven. Kongmu said:

March 11, 2012 at 10:55 pm

Dear Virginia,

Thank you for your nice comment. I’m glad you’ve found some of this helpful. And, if it isn’t clear, please always keep in mind that these are just my thoughts, which may or may not have any validity or value for others. In other words, the important thing in Buddhism is to discover it for ourselves.

You are correct in understanding that Buddhism has prayers for meal time. This is one of the most foundational and practical expressions of the inner life of a Buddhist: awareness, gratitude, and appreciation for that which sustains us. This can be food, water, people, our job, our health, our bodies, among other things. Most important, from our perspective, it also the Teaching of the Buddha that sustains us. Regardless, the prayers before meals are a concrete expression and a vivide reminder of what we are doing when we eat: sustaining the body, appeasing hunger (albeit temporarily), pleasing the mind; all so that we may continue to live and do our best as human beings.

In the Chinese tradition (and all other traditions from what I understand), there are, of course, set verses that are recited before each meal. And, depending on the circumstances, these verses can vary in length from full and complete to abbreviated versions. Unfortunately, I don’t have the time at the moment to describe them here, but I will at some point. It would be a nice topic for a future post, I think.

However, to give you a taste (no pun intended), here’s what are called the “Five Contemplations” before a meal, which appear both in the Chinese and Japanese Buddhist traditions. This is a very rough translation, based on a very sources, as the verse is in very literary Chinese.

===================

食 存 五 觀

shí cún wǔ guān

Five Reflections Before a Meal

計 功 多 少, 量 彼 來 處

jì gōng duō shǎo ,liàng bǐ lái chù

We reflect on the effort that brought us this food and consider how it has come to us.

村 己 德 行, 全 缺 應 供

cūn jǐ dé xíng,quán quē yīng gòng

We reflect on our virtue and practice, and whether we are worthy of this offering.

防 心 離 過, 貪 等 為 宗

fáng xīn lí guò ,tān děng wéi zōng

We reflect on protecting ourselves from greed so as to acquire freedom of mind.

正 視 良 藥, 為 療 形 枯

zhèng shì liáng yào ,wéi liáo xíng kū

We reflect that this meal is only medicine to sustain our life.

為 成 道 業, 應 受 此 食

wéi chéng dào yè ,yīng shòu cǐ shí

We now receive this food in order to accomplish the Buddha’s Way.

==================

Here’s another very common verse, and the one I recite most meals:

=================

飯 前 供 養 文:

fàn qián gōng yǎng wén

Verses of offering before a meal

供 養 佛 供 養 法 供 養 僧 供 養 一 切 眾 生

gōng yǎng fó gōng yǎng fǎ gōng yǎng sēng gōng yǎng yī qiè zhòng shēng

I offer the merits of this meal to the Buddha, the Dharma, the Sangha, and to all sentient beings.

願 斷 一 切 惡

yuàn duàn yī qiè è

I vow to cease from all evil actions.

願 修 一 切 善

yuàn xiū yī qiè shàn

I vow to practice all that is good.

願 度 一 切 眾 生

yuàn dù yī qiè zhòng shēng

I vow to help all sentient beings.

=====================

Hope this helps a bit. I’ll try and offer a bit more in a post at some point.

Thanks again, Virginia. Take good care…..

Reply

virginia said:

March 12, 2012 at 5:38 am

Amitabha. Thank you, your ven. for the verses. I’ve seen a monk of Tantric order stayed solomnly silent before the food he was going to partake, only for a very brief moment, and then he proceed to eat. There is nothing wrong with it.

I’ve copied and pasted the verses for future reading – I hope you don’t mind. To paraphrase what I gathered, we redirect the merit to the three jewels and vow to do only good and help all sentient beings (the merit being the selfless sacrifice of themselves to sustain others). We also need to preceed that with the thought of regret, but be thankful and appreciative of the food, which should be seen as medicine.

Thanks again ven.. Amitabha.

Reply

virginia said:

March 12, 2012 at 5:55 am

BTW, I’m finding that I’m a total 下根 (lowest level in terms of wisdom)]) person because I’ve a tough time understanding and correctly interpreting things in addition to not being able to follow Buddha teachings. But what is upper-level, middle-level, and lower-level? How do we get ourselfves into it? How do we improve the condition? The explanation will help us understand where we stand, and hopefully help us excel to the highest level – sooner :-). Thank you ven.. Amitabha.

Reply

Huifeng said:

April 5, 2012 at 9:57 am

A few more links via:

http://prajnacara.blogspot.com/search/label/repentance

~~ Huifeng

Reply

akosipopoypogi said:

August 18, 2012 at 9:29 pm

Reblogged this on akosipopoypogi.

Reply

Senpo said:

December 1, 2012 at 8:17 am

Ven. Kongmu,

Thanks for sharing these teachings!

Nice to realize such common ground in this path. In some Japanese monasteries of Soto Zen Tradition we practice purification (do you offer incense yourself?), repentance, homage to the Buddhas and Patriarchs(we do turn and kneel facing the altar too!), precepts, and vows. That ceremony is called in Japanese Ryaku Fusatsu and is held (traditionally) every new and full moon at dawn. I am taught it’s a pre-buddhic tradition.

We talk about the meaning of repentance with practitioners who attend such ceremonies here in South america, and the interpretation is about being responsible, to acknowledge our faults, or wrongdoings (and circumstances), etc. , and being pro/active about that, beyond good or bad, guilty or innocent.

In Japanese the Repentance Verse is called “Sangemon” 懺悔文.

I hope to see more of your postings in the future. Even a small comment about an ideogram, provides a precious insight on the practice.

Nine bows.

Senpo (Nanzenji/Argentina)

Reply

caramocha said:

June 28, 2013 at 2:23 am

Hi Venerable Kongmu, I’d really enjoyed this post. I’d shared it with other fellow practitioners. You’d touched upon the deepest misunderstanding that Westerners have on repentance, where most of them cringe at the very thought. Here in the Midwest, we promote a method of Mahayana Buddhism called 地藏七 (or Six Steps Retreat). I don’t know if you’d heard of it, but it started about 5 years ago in China and it has been growing rapidly ever since. One of the things we do is doing full body prostrations to the 88 Buddhas. Most Americans that come to join us out of curiosity view these prostrations as exercise, and we let them think so too lest we scare them away with concepts of remorse and admitting wrong-doings.

Since your venerable seem familiar with the topic, I was wondering if there’s any suggestions you can give us in regards to introducing the practice of repentance to Westerners?

Reply

caramocha said:

June 28, 2013 at 2:29 am

and this is the WordPress blog we have that details our activities around the US. It is in Chinese: http://dizangqi.wordpress.com/

Reply

chunginfodesign said:

July 25, 2014 at 4:34 pm

Excellent Post, Venerable Kongmu.

Also, as we are discussing repentance, I would like to mention the Shurangama Mantra and Sutra. This dharma door is especially relevant to the topic of repentance and very powerful in expiating the evil karmas caused by heavy offenses. Here are some excerpts from the Shurangama Sutra:

“If beings whose minds are scattered and who have no Samadhi remember and recite the mantra, the Vajra Kings will always surround such good people. That is even more true for those who are decisively resolved upon Bodhi. All the Vajra Treasury-King Bodhisattvas will regard them attentively and secretly hasten the opening of their spiritual awareness. When that response occurs, those people will be able to remember the events of as many eons as there are sand grains in eighty-four thousand Ganges Rivers, knowing them all beyond any doubt or delusion. From that eon onward, through every life until the time they take last body, they will not be born where there are yakshas, rakshasas, putanas, kataputanas, kumbhandas, pishachas and so forth; where there is any kinds of hungry ghost, or any being possessing or lacking form, possessing or lacking thought, or in any other such evil place.”

“If these good men read, recite, copy, or write out the mantra, if they carry it or treasure it, or if they make offerings to it, then through eon after eon they will not be poor or lowly, nor will they be born in unpleasant places. If these beings have never done any deeds that generate blessings, the Tathagatas of the ten directions will bestow their own merit and virtue upon these people. Because of that, throughout asamkhyeyas of ineffable, unspeakable numbers of eons, as many as sand grains in the Ganges, they will always be born in places where there are Buddhas. Their limitless merit and virtue will be three-fold, like the amala fruit-cluster, for they stay in the same place, become permeated with cultivation, and never part from the Buddhas.”

“Therefore, The mantra can enable those who have broken the precepts to regain the purity of the precept source. It can enable those who have not received the precepts to receive them. It can cause those who are not vigorous to become vigorous. This mantra can enable those who lack wisdom to gain wisdom. It can cause those who are not pure to quickly become pure. It can cause those who are not vegetarians to become vegetarians naturally.”

“Ananda, if good men who uphold this mantra violate the pure precepts before having received them, their multitude of offenses incurred by such violations, whether major or minor, can simultaneously be eradicated after they uphold the mantra. Even if they drank intoxicants or ate the five kinds of pungent plants and various other impure things in the past, the Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Vajra deities, gods, immortals, ghosts, and spirits will not hold it against them. If they are unclean and wear tattered, old clothes to carry out the practice alone in a place by themselves, they can be equally pure. Even if they do not set up a platform, do not enter a Way-place, and do not practice the Way, but recite and uphold this mantra, their merit and virtue can still be identical with that derived from entering the platform and practicing the Way. If they have committed the five rebellious acts, grave offenses warranting unintermittent retribution, or if they are Bhikshus or Bhikshunis who have violated the four parajikas or the eight parajikas, after they recite this mantra, even such heavy karma can dispense after they recite this mantra, like a sand dune that is scattered in a gale, so that not a particle of it remains.”

“Ananda, if beings who have never repented and reformed any of the obstructive offenses, either heavy or light, that they have committed throughout infinite countless eons past, up to and including those of this very life, can nevertheless read, recite, copy, or write out this mantra or wear it on their bodies or place it in their homes or in their garden houses, then all that accumulated karma will melt away like snow in hot water. Before long they will obtain awakening to Patience with the Non-existence of Both Beings and Dharmas.”