The Four Foundation Yogas of the Tibetan Buddhist Tantra

Lecture 60: The Four Foundation Yogas of the Tibetan Buddhist Tantra

Mr. Chairman and Friends,

As you’ve just heard we’re continuing our course, ‘Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism.’ In the course of this series of lectures we’ve heard first of all quite a bit about the history of Buddhism in Tibet from the very earliest times, from its initial introduction, we’ve heard about schools, like those of the Nyingmapas, the Kagyupas, Gelugpas, and so on. We’ve heard about religious institutions and establishments of various kinds, and also about the Dalai Lama, about lay people in Tibetan Buddhism,

about monks and monastic life, and last week of course we dealt with some, just some, of the symbols of Tibetan Buddhist art.

And today, this evening, we come to something even more practical, something, if I may say so, even more tangible than the symbols of Tibetan Buddhist art. This evening we come, if not to the very heart of Tibetan spiritual practice, at least to its ABC. Today

we’re dealing briefly with what are known as the Four Foundation Yogas of the Tibetan Buddhist Tantra. It may well be that most of you have never heard of these Foundation Yogas before, and this isn’t at all surprising because hardly anything in fact is known about these practices in the West. It might not be an exaggeration to say that nothing is known about them in the West. There are references, very cryptic references, in a few texts which have been translated from the Tibetan and

published in rather obscure journals, so perhaps as I say it would not be an exaggeration even to make the statement that nothing really is known in the West, or even outside Tibet, about these particular practices. But they are, nevertheless, of the utmost importance. Because they are not known about, because they are not well known in the West, it doesn’t mean that they don’t have a very prominent and very important, a very influential role to play in Tibetan Buddhism.

Often we tend to think that if we don’t know about something in the West, nobody knows about it anywhere, rather like as someone recently pointed out, our talk of Columbus discovering America. Of course Columbus discovered America only from the standpoint of those Europeans who, up to that time, had been ignorant of the existence of America. So in the same way these Foundation Yogas may be new to us, but they’re very, very familiar things indeed, very, very familiar ground indeed to Tibetan Buddhists and Tibetan Buddhism. We can say I think that these four practices, these Four Foundation Yogas, these [[Four[Mula Yogas]], constitute the basis of

the whole spiritual life of Tibet. If one doesn’t know something about these practices, if one hasn’t some acquaintance with them at least, then one knows really nothing about the spiritual life of Tibet. You may know all about the Dalai Lama and you may know a certain amount of Mahayana philosophy and so on, but if you don’t know, if you haven’t grasped these practices, and essentially they are practices, if you don’t know something about them, if you haven’t caught the feel of them, then really you know nothing about Tibetan Buddhism at all, spiritually speaking, on the spiritual plane.

And inasmuch, as I’ve said, in the W est these practices are really unknown, even the names of them are unknown, to this extent we may say that Tibetan Buddhism on the spiritual side is simply not known in the West at all. And it’s because of this fact, because these practices, these four Mula Yogas, are so important, because they underpin and undergird as it were the whole vast fabric, the whole vast superstructure of Tibetan religious and spiritual life. It’s for this reason that I’ve decided to devote a whole lecture to these practices.

Now first of all, just a few general observations. Now the practices are called Foundation Yogas or Mula Yogas. Mula is a Sanskrit word. It means literally root. It also means a foundation. And you can speak of either root yogas or foundation yogas because the two terms, the two interpretations, are very closely connected, just as you may have a tree with roots, but the roots are not just roots, the roots are as it were the foundation of the whole tree, the tree stands firmly and squarely upon its roots. If the roots

are weak as we know the tree may topple over. And in the same way we find that if the mula yogas are weak, then the tree, the edifice of the spiritual life which one tries to erect upon that foundation is weak and may also topple over.And therefore we find that in Tibetan Buddhism that the Four Foundation Yogas, the Four Mula Yogas are preparatory to the whole system, to the practice of the whole system of Vajrayana meditation and religious observance generally. In other words they form, they constitute the

entrance, the doorway, the gateway, to the practice of the Tantra. And it is said, it is in fact emphasised in Tibetan Buddhism, that there is no success on the Tantric path, no success in Vajrayana practice if the Four Foundation Yogas, the Four Mula Yogas, are neglected. They come first. You must practise these four first before you can think of embarking on the practice of the Vajrayana, on the practice of Tantric Buddhism.

In the West I know some people have got into the habit of thinking that the Tantra, the Vajrayana, is a short and easy path. We’re always looking for shortcuts, and as soon as you mention the Tantra, the Vajrayana, people’s ears prick up. And you can almost see them or at least feel them thinking, well here’s a nice easy way which, as it were, circumvents all that meditation and all that asceticism and all that study, and you can get it quickly, easily, gaily as it were. Well there’s a certain amount of truth in this. In a sense we may say the Tantra is a short and easy path. One may say that it’s short if one practises it long enough, and one can say that it’s easy if one practises it hard enough!

And the Tibetans themselves one may say often spend years upon years working on these Foundation Yogas, on these Mula Yogas. Years. I’m sure some of you have heard of some Tibetan monks - I believe I mentioned them in an earlier lecture - some Tibetan monks who go into retreat for a period of three months, three weeks, three days, three hours and three minutes. This is a tradition. And sometimes of course they go into retreat for three years and three months and so on.

So you might wonder, well what do they do? There they are shut up in their little hermitage in their cell, with just a glimmering of light coming through a small slit or a small opening and their meal is just pushed through once a day, and they’re all alone there in darkness or semi-darkness in most cases, well what do they do? Well it’s easy enough to say, well they meditate, but just

imagine. Just think of yourself sitting down in a darkened room and just meditating, but indefinitely. You wouldn’t get very far, you wouldn’t know what to do. After an hour you’d be restless, you might be pacing up and down your cell and wondering what to do next. But the Tibetans aren’t like that. When the Tibetans go into this sort of retreat they really do get on with it. One of the things they do get on with, one of the groups of practices with which they do get on is this group of the Four Mula Yogas, the Four Foundation Yogas. And I have known myself personally Tibetan monks, Tibetan yogis, who have said after years of seclusion in this way, it’s remarkable how quickly the time goes. They say the days, the weeks, the months, they just slip by because they’re fully engaged with it, fully occupied with the practices which they find very interesting and the more they go on with them, the more deeply they go into them, the more interesting, the more fascinating even, they do find them.

But this is the Tibetan way. The Tibetans are prepared to devote a great deal of time. They’re prepared to be patient. They’re prepared to practise hard and to practise long. But in the West unfortunately we do tend to be sometimes a little less patient and we do tend very often to expect from our spiritual life, from our spiritual practices, rather quick results. Thus it is perhaps that quite a lot of people tend to neglect the preliminaries of spiritual life, of meditation and so on.

But we can say that the preliminaries, if these are mastered, constitute really half the battle. I know on other occasions in other talks I have gone so far as to say that if you prepare for meditation properly in the full sense then you are already meditating, or at least almost meditating if you prepare yourself properly.

Only too often we tend to think of the means and the end as something sort of sharply separated: the means is a means to the end and you can as it were separate the one from the other. And sometimes we try to have the end, separating the end from the means, but this isn’t really possible. I remember on one occasion Mahatma Gandhi remarked that the end is the extreme of means. If you

really want the end, devote yourself wholeheartedly to the means and forget all about the end. In this way you will gain, sometimes before you’ve noticed that you’ve gained it, the end. So if you peg away at the preliminaries you will find yourself, in due course, deep in the heart of the essentials. But if you try to neglect the preliminaries and jump ahead and leap ahead, then you may not find yourself anywhere at all. Perhaps we’ll return to this topic before the end of the lecture.Now for the meaning of the

word ‘yoga’. We’re dealing with the Mula Yogas, so mula means root, or foundation. What does yoga mean? Now here we must be rather careful, because the meaning of this word ‘yoga’ has been unfortunately rather debased in the West. And nowadays if you mention the word ‘yoga’ to people, well, they’ll take it to mean anything from standing on your head to practising an Eastern variety of black magic! And even in India the word ‘yoga’ is rather ambiguous. It has all sorts of different meanings.

It’s associated with various systems and with various exercises. Literally the word yoga means simply ‘that which unites’ or ‘that which joins’ and it’s etymologically joined with the English word ‘yoke’.

In popular Hinduism the word yoga means approximately simply that which unites one with truth or reality or God, in other words any practice, any way of spiritual life, which brings about a union between oneself individually and the object of one’s worship or the object of one’s quest. And in this way, in this sense of the term, the Hindus speak popularly of say ‘karma yoga’. Karma means

action or work. So karma yoga is the path of union with truth or with reality or with God through work, not just any work, but disinterested, selfless work for the good, for the benefit, of others. And in the same way the Hindu tradition speaks of ‘bhakti yoga’. Bhakti means faith and devotion, so bhakti yoga is the yoga of union with the ultimate, union with the personal God especially through faith and through devotion.

Then again in the more philosophical forms of Hinduism, such as the advice of Vedanta, the non-dualist Vedanta, yoga means the union of the lower self, the Jivatman, with the higher self, the Paratman, (?)or rather perhaps more correctly in the recognition of their basic, their underlying, non-duality or non-difference.

So these are some of the meanings of the word yoga in the modern Indian, especially Hindu, context. But we find in the Buddhist context, especially in the context of Buddhist Tantra, we find that the word yoga has a rather different meaning. In Buddhism, especially in the Tantra, yoga, union, refers especially to the union in the enlightened mind and all along the stages of the path, the union of Wisdom, Prajna, awareness of reality, and Compassion, or universal love, universal loving-kindness. It also means in some more specifically Tantric contexts still, it means the union of the experience of the void, sunyata, which is the general

Mahayana word for ultimate reality, and bliss, especially great bliss, or Mahasukha. And in this context, in this connection, the Tantric tradition usually employs the term Yuga Nada, which is translated and very well translated usually as two-in-one-ness, the two-in-one-ness of wisdom and compassion, the two-in-one-ness of the voidness and supreme bliss. And this two-in-one-ness, this state of non-duality as it were, of unity in difference and difference in unity, this is the highest goal of the whole system of Tantric practice.

Now summing up we may say that the Mula Yogas, the foundation Yogas, are so called because they are practices which initiate the process of integrating one part of our nature with another culminating in the state of perfect integration, integration of wisdom and compassion, sunyata and bliss, at the highest level, which is enlightenment or Buddhahood.

Now the title of this lecture is The Four Foundation Yogas of the Tibetan Buddhist Tantra. Tantra means of course the Vajrayana, in other words the third of the three stages of development of Buddhism in India.

You may recollect, those who attended some of the earlier lectures, that we spoke at some length and more than once I think, of these three successive phases or stages of development of Buddhism in India.

First of all there’s what we call the Hinayana, the Little Vehicle or the Little Way, of emancipation. Now this is generally characterised as ethico-psychological Buddhism, or the ethico-psychological phase or stage in the development of Indian Buddhism. This lasted about five hundred years.

And secondly we have the Mahayana, or the Great Vehicle, or the Great Way or Great Path to emancipation. And this is generally characterised as metaphysical devotional Buddhism or the metaphysical devotional phase in the development of Indian Buddhism. And this also lasted about five hundred years.

And thirdly and lastly we have the Vajrayana, which literally means the Diamond or the Adamantine Vehicle or Path or Way to emancipation. And this is described, this is characterised as the phase or the stage of esoteric meditation and symbolic ritual. There’s much which could be said upon these three phases or stages of development, these three Yanas, the Hinayana, Mahayana and Vajrayana, but this is not the place to go into all that.

As we know, as we have pointed out in earlier lectures, Tibetan Buddhism is a direct continuation, if you like a direct descendant, or if you like even a rebirth, a reincarnation, of Indian Buddhism, on the soil of Tibet. And in Tibetan Buddhism therefore all three Yanas are represented. In fact, as I did try to make clear some weeks ago, Tibetan Buddhism, like Indian Buddhism of the Pala (?) dynasty, is a synthesis of all three. It’s a synthesis of Hinayana, Mahayana and Vajrayana. It’s in a way a non-sectarian tradition.

To illustrate this we may say that the monastic discipline of Tibetan Buddhism, as well as its general Buddhist teaching, and the Abhidharma, these all come from the Hinayana, especially the Hinayana in its Sarvastivada form. Then again the sunyata philosophy, the teaching of the voidness which underlies all forms of Tibetan Buddhism, and the Bodhisattva Ideal, which is the spiritual ideal of all forms of Tibetan Buddhism, these come from the Indian Mahayana. And then the spiritual practices, the rites, the ceremonies, the meditations, the symbolism, of Tibetan Buddhism, these all come from the Vajrayana. So in this way we see that Tibetan Buddhism is a Triyana system of Buddhism.

Now the Four Foundation Yogas constitute the introduction, the entrance if you like, to the Vajrayana, to the practice of the Adamantine or the Diamond Path or Way. So at this point a question arises, or a question may be raised. Tibetan spiritual practice, as distinct from doctrinal study and institutional life, Tibetan spiritual practice is mainly, if not exclusively, Tantric. Now the Vajrayana, or the Tantric phase of Buddhism, is the third, and the highest stage in the development of Buddhism. So the question which arises is, does this mean that the

spiritual practices of the Hinayana and the Mahayana are ignored in Tibetan Buddhism, inasmuch as Tibetan Buddhism gets started for all practical purposes straight away with Vajrayana. It starts on the Four Foundation Yogas and then goes on to the Vajrayana. W ell it may seem as though they were neglected, the spiritual practices of the Hinayana and the Mahayana, but it isn’t really so, because as we shall see these practices, or rather the most important of them, are incorporated into the M ula Yogas themselves.

However all this is general, all this is introductory to the Mula Yogas, so perhaps it is time that we got on to the Mula Yogas themselves and described them individually.

As must have been evident already, there are four of them, and I’m just going to enumerate first of all these four, and let you know briefly what they are.

The first Mula Yoga, the first Foundation Yoga, consists in The Going For Refuge and Prostration.

The second consists in The Development of the Bodhichitta, or Will to Enlightenment.

The third consists in The Meditation and Mantra Recitation of Vajrasattva and

the fourth consists in The Offering of the Mandala.

In previous lectures I’ve spoken of the four principal schools of Tibetan Buddhism, that is to say the Nyingmapas, the Kagyupas, the Sakyapas and the Gelugpas. When it comes to these four foundation yogas, these four mula yogas, we find that they’re the same, these practices are the same, for all these schools.

Sometimes the order of practice is a little different and sometimes certain details vary, but substantially these four are the same.

But so far as this evening’s explanation is concerned I’m going to follow mainly the Nyingmapa tradition of the four mula yogas or four foundation yogas, not because I feel that the Nyingmapa tradition is right and that the others are wrong, not even because I feel that the Nyingmapa tradition is better and the others are perhaps a little worse, but more especially because my own personal connection in this respect happens to be more with the Nyingmapa version of these four mula yogas. I’m not going to go in to variations of detail so far as the practice of the yogas is concerned as among the four schools.

Now for the mula yogas individually. It won’t be possible to give a complete description of these practices because they’re much too complex, even though by Vajrayana standards they’re rather simple practices. Now first of all The Going For Refuge and the Prostration. Going For Refuge, going for refuge to the Buddha, to the Dharma, to the Sangha, this is of course a very common practice in all schools of Buddhism, whether it’s the Buddhism of Ceylon, or Thailand, or Tibet or Japan, one finds on all possible occasions people ‘Taking the Refuges’ as it’s called, and Going For Refuge.

But though it’s a very common practice all over the Buddhist world, one has also to say, one has also to recognise that the Going For Refuge is not always taken very seriously. I know that in India for instance, when there are public meetings, even mass meetings, with various political figures on the platform and where there’s a mainly non-Buddhist audience, some people still insist on giving the Refuges and getting everybody to recite them even though it has no significance. It’s just recited as a sort of chant. But this is really an abuse of the tradition.

In the Tantric Buddhism of Tibet on the contrary we find, not only that the Refuges are taken very seriously, but they’re treated as an important spiritual practice in their own right, and this is how they come to figure, or the Going For Refuge and Prostration comes to figure in the Four Mula Yogas.

Now as practised as the first of the Mula Yogas as they are in the Going For Refuge and Prostration, three main elements and these are a visualisation, a recitation and the prostration. And these three main elements correspond to body, speech and mind. You might have noticed in the course of the last few lectures, and even lectures which I’ve given on other aspects of Buddhism, that in

Buddhism there’s a constant reference to the distinction between body, speech and mind. Just as say the Christian tradition speaks of body, soul and spirit, in the same way the whole Buddhist tradition, not only that of Tibet, speaks of body, speech and mind.

It’s not just body, speech and mind in the literal sense, but we haven’t got time to go into that this evening. But these three, howsoever one understands them, are taken as exhausting the whole content of human, for want of a better word we call human

personality. If we take our body, our speech and our mind, we’ve got us as it were. These are our three principal aspects, our

three principal modes of functioning: the physical, the communicative, and the mental or spiritual. So in any complete practice, any complete spiritual practice, all three must be provided for. And this is why in the Going For Refuge and Prostration Practice there are these three elements: visualisation, which is something done by the mind, it’s a sort of meditation, recitation, which is done by the speech, and prostration, which is done by the body. And in this way the whole being, the whole personality, is involved.

This is one of the basic points of the Tantra, that it isn’t enough to do something mentally, you’ve got to do it verbally, you’ve got to do it physically. The whole being, the whole personality has got to be involved. And this is, as I say, one of the main characteristics, one of the principal features, one of the dominant features, of all Tantric practice.

Now first, the visualisation. So what is it a visualisation of, this mental side, this mental element, in the Going For Refuge and the Prostration? This is the visualisation of what is known as The Refuge Tree. Now I’m sure you’ve all heard of the Refuges, but I don’t suppose many of you have heard of a Refuge Tree, but this is what has to be visualised, a Refuge Tree. So what does a Refuge Tree look like? Because obviously if you don’t know what it looks like you can’t visualise it very easily. So I’m going to try to describe this, and I’m going to ask you not to so much follow my words as to try to sort of build up the picture within your own minds of what the Refuge Tree looks like.

So you have to visualise first of all an enormous lotus flower, in fact a whole lotus plant. It has to be enormously big, as big as a great oak or a great elm, which is very, very big indeed. And there’s one great thick central stem to this lotus and there are four as it were branches, rising out of the central stem, in the direction of the four cardinal points, north, south, east and west. So you’ve got the great central stem in the middle, and then at the four cardinal points you’ve got the four branches. And each of these five, that is to say, the central stem and each of the four branches, terminates in a gigantic lotus blossom, so that there are five flowers in all. So this is what you have to visualise first of all, this enormous Refuge Tree, this great plant with these five enormous blossoms.

Now when you’ve got that firmly in your mind, when you can see that quite clearly, then you direct your attention to the central lotus. And you should see, at the calyx of the flower, you should see the rows upon rows, the layers upon layers of petals, folded back, and then right in the centre, as it were sitting on or in the calyx of that central lotus, one should visualise the founder of the tradition of practice, the tradition of Tantric practice, that is to say, to which one belongs. For the Nyingmapas of course this is Padmasambhava. For the Kagyupas it’s Milarepa. For the Gelugpas it’s Tsongkapa and so on. But one visualises this figure, the founder of one’s own particular tradition of Tantric practice, firmly seated, right in the middle of the calyx of that central lotus.

So one visualises clearly, and not only visualises, but one thinks of that central figure seated there as being the embodiment of all the Buddhas, all spiritual perfections, all enlightenment, all wisdom, all compassion, all peace, all perfection, all concentrated in that figure, that is the supreme embodiment, as it were, of one’s highest spiritual ideal in all possible aspects, in all possible manifestations. So this is the next stage.

Then you go a little further. And you notice that the lotus has many tiers of petals, sort of folding back, more like a chrysanthemum than a lotus, but obviously there are difficulties of representation. And then you visualise, underneath the figure of Padmasambhava or Milarepa, as the case may be, you visualise, one on top of the other as it were, one’s other lamas or one’s other gurus, terminating in one’s own personal guru, and then above him but still below say Padmasambhava or Milarepa other gurus of the line, or other masters from whom one has received instruction, and so on.

And then lower down still one visualises, still in line with that central lotus, one visualises what are known as the four orders of Tantric deities: Buddhas ,Bodhisattvas, peaceful and wrathful, and so on, in other words, the deities of the four Tantras, the four classes of Tantra. And then lastly underneath them one visualises the dakinis and the dharmapalas.

Now you might be wondering, what is this all about? And why does one visualise in this way? It’s pretty obvious why one visualises the founder of the lineage of Tantric spiritual practice, whether Padmasambhava or Milarepa, but why these others? Why the lamas? Why the four orders of Tantric deities? Why the dakinis and dharmapalas? Well these represent the Tantric or Vajrayana, that is to say, the esoteric aspect of the Three Refuges themselves. There are three exoteric Refuges, there are three esoteric Refuges and there are also three secret Refuges and three suchness Refuges. I think this is new ground to most people, but this evening we are going only so far as the three esoteric Refuges.

The three exoteric Refuges are of course the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha. The three esoteric counterparts of these are first of all the Guru, who is the esoteric counterpart of the Buddha, then the deities of the path, which are sort of archetypal embodiments or symbols of spiritual experiences which are the esoteric aspects of the Dharma, and then the dakas and dakinis and dharmapalas, which represent the persons or even the spiritual forces, if you like the occult forces in the company of which, or with the help of which one practises and follows the Path and they represent the esoteric aspect of the Sangha.

So in other words it means that in line with that central lotus you’ve got the symbols of the esoteric aspects of the three Refuges. Sitting on the calyx of the central lotus flower first of all you’ve got the founder of the whole line of Tantric practice and underneath him (in order) the esoteric, or rather the symbol of the esoteric aspect of the Buddha Refuge, the symbols of the esoteric aspect of the Dharma Refuge, symbols of the esoteric aspect of the Sangha Refuge.

So in this way you’ve got your esoteric three Refuges lined up vertically underneath that central figure on the central, or on the calyx of the central lotus blossom.

Right, having dealt with the first lotus, let us go on to the other lotus blossoms. You’ll remember that there’s one lotus blossom right in front, which is the southern one as it were. Well on that you’ve got Sakyamuni, the human, historical Buddha, with other historical Buddhas, usually there are just three, with the Buddha of the past, Dipankara, to the left, and the Buddha of the future, Maitreya, on the right. So therefore, on the lotus blossom to the south as it were you have these representatives of the human and historical Buddhas.

Then on the lotus to the left, that is the left of oneself, there are the Bodhisattvas, usually the eight principal or ten principal Bodhisattvas. And they represent the Sangha, the spiritual community, in the purely Mahayanistic sense. And they include, say, Avalokitesvara, Manjusri, and so on. Then the rear lotus, or the lotus to the north behind the central lotus, one sees a heap of sacred books. And this of course represents the Dharma, the sacred scriptures.

And then on the lotus to the right, the eastern lotus as one may say, one sees an assemblage of Arhants, those who’ve gained enlightenment or liberation for themselves alone. And they constitute the Sangha, the spiritual community, in the Hinayana sense. So they include the great arhants disciples of the Buddha like Sariputra, Moggallana and so on.

There are a number of other details which could be gone into regarding the refuge tree and the lotuses and so on, but I don’t think we’d better go into all that this evening.

Now the whole tree, the whole tree, with the central lotus and the four other lotuses, with the central figure of the founder of the whole line of practice, and the lamas, the deities of the Tantric path, the dakinis, dakas, dharmapalas, then the Buddhas of the three periods of time, the Bodhisattvas, the Arhants, the sacred books and a number of other figures too, these all have to be visualised fairly clearly or, if possible, quite clearly and quite vividly before one begins. If one is actually doing the practice one sits as for meditation and builds up this mental picture in one’s mind first, this picture of this Refuge Tree.

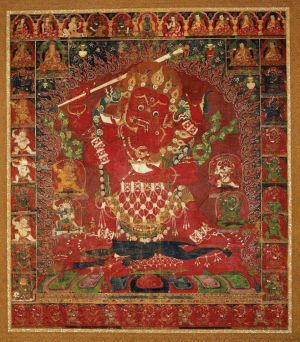

Tibetans themselves have got, are familiar with the appearance of the Refuge Tree, from thangkas, from the painted scrolls, it’s a quite popular subject. It isn’t easy to get hold of copies of this particular painted scroll because so many figures are involved and they have to be so tiny, that it’s an enormous amount of work for the artist, and very few artists are ready to undertake just one single thangka of this kind, which may keep them busy for months and months and months. I remember I did manage to procure one

once in Kalimpong, but it was begged from me from one of my friends, in fact it was the present Tomo Geshe Rimpoche, who wanted it for a newly founded monastery, and as he didn’t have one I gave it to him. But I do have a print, and in this connection I might mention that we shall be showing after the last, after the eighth of these talks, some slides, some colour slides, illustrating some of these things, including the Refuge Tree. So one will have an opportunity of visualising, perhaps a little more clearly then than perhaps one is able to do now.

So this is the mental element in the whole practice, the whole practice of Going For Refuge and Prostration. This is what one visualises. One visualises the Refuge Tree. One visualises, one has the feeling of and feeling for all these great spiritual figures, all these symbols, all these archetypal forms, which together make up the content as it were of that Refuge Tree.

Now the verbal element in the practice consists in the repetition aloud of a formula expressive of one’s Going For Refuge to the founder of the whole tradition as the embodiment of all the Refuges.

In other words, if one follows the Nyingmapa tradition, if the central figure of the Refuge Tree is say Padmasambhava, then one’s formula expresses one’s taking refuge in Padmasambhava as the embodiment of all the Refuges, as the embodiment of the Buddha Refuge, Dharma Refuge, Sangha Refuge, and so on.

This formula naturally varies a little so far as the words are concerned, from one tradition to another.

Because if you follow the Kagyupa tradition, well your central figure will be Milarepa, you take refuge in him as the embodiment of all Refuges, and so on. So this is the verbal element in the whole practice, the repetition of this formula expressive of your going for refuge to the founder of the line, the founder of the lineage of spiritual practice, of Tantric practice, as embodiment of all the refuges.

Now finally there’s the physical element in the practice and this is represented by the prostration, the prostration, full length prostration. As I’ve said, the body occupies an important place in the Vajrayana. In some forms of Buddhism one finds that the body is depreciated, as in some forms of primitive, of early Christianity. Sometimes the body’s referred to as this animated corpse and

this bucket of filth that you’re carrying around with you and picturesque expressions of that kind. But not in the Vajrayana. In the Vajrayana it’s a sin to speak in dispraise of the body and the senses generally. Because they say that the human body is the vehicle for emancipation. The human body can become a Buddha body, so therefore it’s very important, it’s very precious, it’s very prized. It’s not to be looked down upon and not to be despised.

So the Tibetans have this very definite, this very positive idea, and the Tantra has in especial this verydefinite, this very positive idea, that the body also must be involved, that your spiritual practice is meaningless if it doesn’t involve the body, if the body doesn’t participate. It mustn’t be just a mental thing, not even a mental plus verbal thing, but a mental plus verbal plus physical thing. And the Tibetans believe that religion must be physical as well as verbal and mental.

And therefore, as one might have expected, Tibetans spiritual life tends to be very, very strenuous. Not for the Tibetan the sitting down in a cosy corner and reading a book about the spiritual life. He doesn’t look at it like that . And I remember often hearing from the lips of my Tibetan friends a little proverb which said, ‘Without difficulty, no religion’. If it’s easy, then it isn’t a religious practice. If it’s difficult it probably is. If it’s very difficult, it’s probably quite a good practice. But they

don’t take it easy. And you find that Tibetans’ spiritual life is very strenuous and it involves a very great deal of physical exertion. This is of course partly on account of the very atmosphere, the temperature of Tibet - after all, if you’ve got snow outside your monastery you need something strenuous to keep you warm, but this is only part of the reason, part of the explanation. They feel that the body also must be involved and if the body is not involved, is not doing something of a spiritual nature, then you’re not really seriously practising. And this is why you find Tibetans doing things like prostrating themselves all the way from

Lhasa to Bodh Gaya, something well, it’s a distance of about, what, five, six hundred miles. We’d think this perfectly crazy! Well, the Tibetans don’t, they take this very, very seriously indeed, and they respect very highly people who do this sort of thing.

So therefore in this Going For Refuge and Prostration practice, you don’t just visualise, you don’t just repeat this formula of

Going For Refuge, you also prostrate, you fling yourself down full length in front of the visualised Refuge Tree with all its lamas and deities and so on. And the prostration is the full one. There are various forms of prostration. In India they usually have the abbreviated one, but not the Tibetans. They always go the whole hog. They have the full one, right down on your hands and knees, and flat on your face in fact and with your arms shooting out in front of you. They do it in fact rather dramatically and not to say powerfully and impressively.

And all these three, that is to say the visualisation, the repetition of the formula and the prostration, all these three have to be done simultaneously. Of course to get into the way of it, just to get the hang of it, you can practise separately, but when you do it properly, you do altogether. You keep the mental picture in your mind, you repeat the formula and you fling yourself down. There’s a prescribed way of doing this. And in this way mind, speech and body are all co-operating. Mind, speech and body all practising. Mind, speech and body are all being influenced, all participating in the particular practice.

And there is a certain effect. It’s very difficult, in fact it’s impossible, to describe the effect and this is known only to those who have had some experience of this sort of practice. W ell perhaps I should mention that according to tradition you have to do this whole thing one hundred thousand times, one lakh of times.

And they say that if you’re doing it full time it’ll take you about three months. But if you’re just able to do a few hundred a day, which isn’t really very much, though it takes maybe a couple of hours, then of course it’ll take you several years. But the idea is to do as many as you possibly can. And believe me, when you’ve done these, even a few, the effect is quite tangible and sometimes even quite remarkable.

In case this all sounds very, very difficult I should mention that the Tibetans themselves do also follow the tradition of taking up other practices, Vajrayana practices, before you’ve actually finished your preliminary practices. In other words you can be adding to your total of prostrations - you might have got up say to 10,456, but you can

at the same time say be doing the meditation on Tara, on Manjusri, or even something more advanced than that and as it were continuing and trying to complete your preliminary practices while you have already embarked upon the Tantric or Vajrayana path proper. This is perhaps a concession to the corruptions of modern times, but the Tibetans themselves all do this.

All right. One may say about the Going For Refuge and Prostration in conclusion that it represents the Hinayana component in the Four Foundation Yogas. The whole of the Hinayana in a way can be summed up in the Going For Refuge to Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. So the Going For Refuge and the Prostration practice as the first of the M ula Yogas represents their force within a specifically Vajrayana or Tantric context, the Hinayana component in the whole group of practices.

Now secondly we come to the development of the Bodhichitta, or the Will to Enlightenment. And one develops this first of all by developing compassion for all living beings. This is a sentiment or an aspiration which resounds or reverberates throughout the whole of Buddhism, the development of love and compassion for all living beings. But the Tibetans here as elsewhere, they give their own particular twist if you like, their own particular colouring to this universal Buddhist idea.

They say that should look upon, one should regard, all living beings as being just like one’s own parents, one’s own mother, one’s own father.

Because the Tibetans, like most other Buddhists, they believe very strongly in rebirth and reincarnation, and they believe that if you look far back enough, that everybody you know, everybody you meet, has at some time or other, in some previous life or other, been your mother or your father.

So the Tibetans attach a great deal of importance to this. In practice they emphasise it very, very strongly and for Tibetans this is a very, very vivid and very real thing. To us of course, even if we do happen to be Buddhists, sometimes the idea of rebirth and reincarnation, though we accept it intellectually perhaps, with more or less of reservation, it doesn’t really get into our bones.

But in the case of the Tibetans it is really in their bones and their blood and they feel it very strongly, and if they are serious minded, if they practise any kind of Tantric exercise, they can actually feel that the people that they meet, at one time, in the remote past, were as closely related to them as that, and therefore they feel that they should be kind to them, they should love them, they should be affectionate towards them, and treat them properly and decently.

So therefore the Tantric tradition emphasises that inasmuch as one has this love, one has this compassion for all living beings, all sentient beings, one should develop the resolve to help them, to deliver them from suffering. And the Tibetan tradition especially emphasises, it’s only if you feel for others as though they were your own parents, that you’ll feel the urge, really to help them in difficulties. And they give a rather beautiful sort of illustration for this.

They say that suppose one day you’re going through the bazaar. This can be a common experience in Tibet as in India, you’re going through the bazaar, and there are people selling vegetables and all sorts of other things, pots and pans all around you, and there’s a noise and a crying of goods of various kinds, and maybe as you go through the market you notice that in some corner there’s some disturbance going on, some sort of a row. This often happens in bazaars, no-one takes too much notice, not until people start killing one another.

But for some reason or other you sort of stop, and you just look and you see there’s quite a crowd and there seems to be someone in the middle who’s sort of getting the worst of it. So just out of curiosity perhaps you think, well let me go and have a look. So you draw nearer and you see that there’s a great crowd of people and for some reason or other they’re beating and thrashing someone

in the middle, who’s down on the floor. I mean, kicking and knocking over the head, so you think well, it’s not too good, but anyway it’s none of my business sort of thing, well anyway, out of curiosity you go a little nearer, and then you see, well, it’s rather a pity, it’s a woman that they’re beating, all these big, hefty men, it’s a woman, in fact it’s an old woman that’s being

beaten. And you get a little bit nearer, you get a little bit interested, you’re still not very interested, but as you get into the throng, as you really look, you see, good heavens, this is my own mother being beaten. And you didn’t know your mother apparently has gone to the bazaar and there she is, she’s got into some trouble and she’s being beaten. So at once you feel tremendous compassion, tremendous love for the mother wells up in the heart then, because you recognise that the person who is being beaten, the person who is suffering is near and dear to you.

So therefore the Tibetan spiritual masters say that if you can see in each suffering human being your own mother or your own father, or someone near and dear to you, then the love, then the compassion will well up in your heart, otherwise not. And this is why they emphasise this so much, because we can see so much suffering all around us, we

can see people having their heads cut off, or we can read in the newspaper that 70 people were killed in an accident, or 25 people were killed in a fire, or several hundred killed yesterday in Vietnam. W e just turn over to the next page in the newspaper and look at the sports results. And we don’t think anything of it because no-one near and dear to us is involved. This is why we are so, in a sense, callous.

But the Tibetan tradition says one shouldn’t look like that. One should try to see, try to feel, all living beings as deeply, as intimately related with oneself. So they make use in this connection of this idea of karma, rebirth, reincarnation, and they say, well, try to feel, try to look back and try to act as though as in fact is the case, all the people, all the beings, with whom you

are at present in contact, are in fact your own reincarnated mothers, fathers and so on of previous lives, of previous existences.

So when one sees all the beings around one, all the suffering beings around one, in this way, in this light, as one's own parents as it were reborn, then out of compassion one develops a tremendous urge to deliver them, to lead them on the right path, to lead them to Buddhahood, to lead them to enlightenment. And therefore one makes a sort of vow, a sort of resolve, a sort of resolution, that one will gain enlightenment, gain Buddhahood, through the practice of the Vajrayana, through the practice of the Tantra, so that one may function as a spiritual teacher in the world.

So this mula yoga, this foundation yoga, consists mainly in the repetition, like the repetition of a mantra, of a formula expressive of one’s resolve, of one’s determination, to gain enlightenment, to gain Buddhahood, for the sake and for the benefit of all living beings. And this is of course the famous Bodhisattva Vow.

So one may say that in brief the second of these mula yogas consists in the repetition again and again and again in a certain way, according to the instructions of the teacher, of a formula expressive of the Bodhisattva Vow, one’s determination to gain enlightenment, not just for the sake of one’s own personal emancipation, but for the good and welfare and benefit for the whole world of sentient beings. So this too is to be repeated and recited one hundred thousand times.

And you’ll notice of course that the Vajrayana is very fond of repetition. This is one of the great features of the Vajrayana, that they do this ten thousand times, do that a hundred thousand times, do that a million times, over and over and over again. And the reason for this is that there’s a tremendous need to penetrate, to break through if you like, into the unconscious mind. Usually we

just repeat something once and we think we’ve understood it and we put it aside. That’s that. I vow to gain enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings. What could be easier than that? That’s the Bodhisattva Vow, you’ve repeated it, you’ve recited it, you’ve taken it. But there’s not even a scratch on the surface of the mind. So therefore the Vajrayana says, go on repeating it. Go on repeating it. Say it a thousand times, ten thousand times, a hundred thousand times, a million times, and maybe, when you’ve

done it maybe a hundred, two hundred thousand times, the meaning will begin to percolate, begin as it were to soak down below the level of the conscious mind into the unconscious mind and start influencing it there where it really matters. So a hundred thousand repetitions of the Bodhisattva Vow at the time of the actual practice.

And in between, as it’s called, in between two sessions of actual practice of the foundation yogas, one should reflect in a certain way.

One should reflect that with every out-going breath that one breathes, that with every out-going breath one’s good qualities, such as they are, fall upon others like moonlight and confer happiness upon them. In other words one should feel that one’s effect, one influence, upon others is beneficent and positive, just like that of the moonlight. Here of course obviously we’ve got a reminiscence of Indian tradition because in India after the heat of the day at night the moonlight is cool and soft and beautiful

and people appreciate it very much. So your influence on others should be like that. You should fall like moonlight upon others and your whole influence should be soft and gentle and beneficent. So those who practise the mula yogas have to ask themselves (?) whether they have upon others the effect, would your best friend compare you with moonlight? You have to ask yourself that question.

And then with every in-going breath one should feel that the sins of all beings, the weaknesses, the imperfections of all beings, are entering one’s own body and are being absorbed into, annihilated in, the Will to Enlightenment itself.

And also if one has time one should practise the Brahma Viharas, the four sublime abodes, that is to say, love, compassion,

sympathetic joy and equanimity. And these are known to most of you I think, no need to describe them in detail. So the Brahma Viharas are incidentally common practices in both the Hinayana and the Mahayana. So we may say that the development of the Bodhichitta, the Will to Enlightenment, and the repetition of the Bodhisattva Vow represents (?) the Mahayana, the Great Vehicle or Great Way component in the Four Foundation Yogas.

Now we come onto 3) The Meditation and Mantra Recitation of Vajrasattva. This mula yoga may be considered the most important of the four foundation yogas generally. It’s purely Tantric. The Going For Refuge and Prostration represents a Hinayanic component within the four mula yogas, the development of the Bodhichitta, the Will to

Enlightenment, represents a more Mahayanic component, but the third mula yoga, the Meditation and Mantra Recitation of Vajrasattva, represents the purely Tantric component, the purely Tantric element in the whole group of practices. And this is undertaken for, what the tradition calls, Purification of Sins.

I remember in this connection that I knew in Kalimpong a French woman who became a Buddhist nun and she had been a Catholic. And she said as a Catholic she heard a lot about sin. But she said it wasn’t until she started practising the Vajrayana that she really heard about sin and about purification from sin! And the Vajrayana does attach great importance to this, and places a great

emphasis on it. Its conception of sin isn’t quite that of course of Christianity, but it does recognise in a very realistic way that our minds are encumbered by all sorts of murk, all sorts of dark and rather dirty things that we’d rather forget about. But unfortunately if we are to get anywhere with our spiritual practice we have to drag them all out into the light of day, into the light of the Buddha, and dissolve them. And at least to recognise that they’re there and see them clearly, and face up to them,

before they can be purified. Purification is possible, but the condition (present?) is that at least we recognise the need for purification. So this Vajrasattva yoga as it’s also called, the meditation and mantra recitation of Vajrasattva, is undertaken for purification from sins.

First of all, a few words about Vajrasattva himself. ‘Vajrasattva’ usually is translated as the Diamond or Adamantine Being. Vajra is the diamond or the thunderbolt, sattva is being. This’ll do for the present, we’ll see a little later on what it really means. Iconographically Vajrasattva is a Buddha in the

form of a Bodhisattva. And sometimes Vajrasattva is called the sixth Buddha. Sixth Buddha means the esoteric Buddha, the hidden Buddha if you like and the Tantric tradition speaks of a sixth Buddha, much as we might speak of a sixth dimension, something very mysterious sounding which is almost a contradiction in terms, something which is just a sort of ‘x’ quantity which you don’t really apprehend.

Now to understand why Vajrasattva is spoken of as the sixth Buddha, not as the tenth or the eleventh and so on, to understand why Vajrasattva is spoken of as the sixth Buddha, we have to refer to the scheme of the five Buddhas. The five Buddhas - I’ve spoken about them at length on other occasions - the five Buddhas are the transcendental counterparts, in personal Buddha form, of the five aggregates, the five constituents of conditioned existence.

They’re the five archetypal Buddhas if you like, the five ideal Buddhas, so that you’ve got five different colours: there’s a red one and a yellow one and a green one and a blue one and a white one, and when they are depicted in the mandala, when they are depicted in the circle of symbolic forms, you get one in the centre, one Buddha, one archetypal Buddha in the centre, and one at each of the four cardinal points. And the usual arrangement, the usual arrangement is to have Akshobya, which means the Imperturbable One, the dark blue Buddha, in the centre.

And then to the north you’ve got Amoghasiddhi, Infallible Success, the green Buddha, to the south Ratnasambhava, the Jewel-Born Buddha, or the yellow Buddha, to the west Amitabha, the Infinite Light, the red Buddha, and to the east Vairocana, the Illuminator, the white Buddha. So in the centre the

dark blue Buddha, then to the north the green Buddha, to the south the yellow Buddha, to the west the red Buddha, to the east the white Buddha.

The names don’t really matter very much, it’s the principle which is important. The central Buddha is a synthesis of the other four Buddhas. The other four Buddhas represent fragmented aspects of the main, the central figure. Just as white light is a sort of synthesis of all the colours, the seven colours of the rainbow, in the same way the central Buddha figure, in this case Akshobya, the dark blue Buddha, the Imperturbable One, is the sort of synthesis, the integration if you like of all the other Buddha forms and Buddha aspects.

Now Vajrasattva is the esoteric aspect of the central or the fifth Buddha. You can only represent or depict Vajrasattva in the mandala by imagining him as being behind the central Buddha in a different dimension as it were. So he’s the sixth Buddha, sixth not in the sense of being added to the five, but as it were standing outside the plane on which the five Buddha differentiation is made.Now it’s one of the fundamental

principles of the Tantra and of Tibetan Buddhism generally that all the Buddhas, all the Bodhisattvas, dakas, dakinis, dharmapalas and so on are to be found within one’s own mind, not within the ordinary individual mind, so-called subjective mind.

To find them within one’s own mind one has to go deeper than that. So Vajrasattva also, the sixth Buddha also, is to be found within the depths of one’s own mind. He is to be found at a point beyond space, beyond time. Vajrasattva represents, really represents or symbolises the primeval purity of one’s own mind. One’s own mind in its original, beyond space and beyond time

purity, its transcendental purity, its absolute purity. This is what Vajrasattva represents or symbolises. In other words, Vajrasattva symbolises the truth that whatever you might have done on the phenomenal plane, whatever sins you might have committed, however low you might have sunk in the scale of being and consciousness, your basic mind, your true nature if you like to use that expression, remains pure, remain untouched, remains unsullied, that in the depths of your being, whatever you might have done or not done, you are pure.

Now obviously this sort of teaching can be misunderstood. It’s a deeply metaphysical teaching, not just a psychological teaching. But in Tibet at least in the old days misunderstanding was unlikely.

Now the purpose of the whole Vajrasattva yoga, the purpose of this third mula yoga, is to re-integrate us with our own innate purity, to as it were purify our sins or purify us of our sins by the realisation, the recognition that underneath the sins there is an immaculate purity of our own mind

which has never been touched and never been tainted. In other words, you purify yourself from your sins, which you acknowledge your sins on their own level by realising that in the depths of your being you have never sinned, that you are primevally pure. This is the essence of this whole practice.

So how does one proceed? How does one do it? First one visualises Vajrasattva, another visualisation exercise. One visualises immediately above one’s own head, as brilliant white, like snow, youthful - the texts say sixteen years of age, which is supposed to the ideal age so far as beauty is concerned - and with a smiling expression. And then one

visualises the bhija, the seed syllable, Hum, blue in colour at the centre of the heart of this visualised Vajrasattva figure and surrounded by the letters of the, or rather the syllables of the hundred-syllabled mantra. This requires a little explanation if one is not to misunderstand. These visualised letters all stand upright, and the circle of letters, the hundred letters (sic) of the Vajrasattva mantra, they stand upright around the central bhija. They’re not as it were laid down flat, as on a clock face.

It’s rather as though you sort of swivelled the clock face and put it flat, horizontal, and then you stood all the figures up in their places. This would represent the sort of arrangement which one has in mind here.

So one visualises, first of all this white figure, youthful, smiling, and so on, visualises the bhija, the seed mantra, visualises the hundred syllables of the hundred-syllabled mantra around it, all white, all emitting light and so on, and then from these one visualises a stream of what is described as milk-like nectar which descends from these mantras and descends into one’s body through

the central aperture and which goes right through the body and washes out all sins. So one has to visualise this and feel this. And with a little practice you can actually feel this sort of cold or cool sensation coming, descending into the top of the head and then flowing down through the whole body and even filling the whole body. And one has to feel

that one becomes eventually like, or one’s body becomes like, a crystal vase filled with curds. This is a traditional comparison. You feel so clean, so pure, so purified that this is the sort of experience. Or it’s also said you feel like clear, void light.

After you’ve done this practice, after you’ve visualised the Vajrasattva figure, the mantras and the flow of this milk-like nectar through one’s whole system one feels completely purified, transparent like glass or crystal or even like void and pure light. And all this has to be visualised. And all these visualisation exercises have this corresponding psychological effect. And having done the visualisation one then recites the hundred-syllabled mantra one hundred thousand times - not at one sitting of course, you can do it two or three times or ten times or a hundred times at one sitting and then add up the total day by day or week by week.

The mantra itself by the way, the Vajrasattva mantra, which is a very famous mantra, expresses the idea of re-integration with one’s own original Vajrasattva nature. At the end of the practice there are several othervisualisation exercises, but I don’t propose to go into that this evening.

At the end of all the practices Vajrasattva, the visualised Vajrasattva, is dissolved back into the void, into the sunyata. This is the usual procedure at the end of a visualisation exercise, as we shall see in greater detail next week.

Well fourthly and lastly the Offering of the Mandala. The mandala is not the same here as the circle of symbolic forms. Here a mandala means a symbolical representation of the entire universe according to ancient Indian cosmological traditions. The ancient Indians had their own views about the nature, the constitution, of the physical universe, so the mandala is a symbolical

representation of the universe according to these ancient Indian traditions. And the practice consists in offering this mandala, offering this symbolical representation of the whole physical cosmos as it were to the Three Jewels, the Buddha, the Dharma, the Sangha, in their exoteric as well as in their esoteric

aspects. And these three, the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha, in these two aspects, exoteric and esoteric, are to be visualised more or less as in the Going For Refuge and Prostration practice except that here there is no tree.

So how does one do this? First of all one performs the sevenfold puja. You’re all familiar with the sevenfold puja which we celebrate after the lecture every evening here and on other occasions, but in this context it’s not the ordinary Mahayana sevenfold puja, but it’s a special esoteric Tantric version of that sevenfold puja. There’s no time to explain all these things at the moment. And having performed that Tantric version of the sevenfold puja one builds up and one offers the Mandala. The Mandala, the

symbolical representation of the universe, is made up of thirty-seven parts and one constructs it on a circular copper base by heaping rice and then putting rings around, rings of copper or silver and so on, until one has built up a sort of conical or sort of pyramid-like structure with different tiers and different heaps of rice which one places at intervals all around the foundation

and also at higher levels and represent different elements in the physical universe, and one has to bear these in mind and repeat their names when one is building up this particular model as it were. It’s all too complicated to describe in detail.

But there are several ways of offering. The usual way is that when one has built up the mandala, using the copper or silver base

and heaping with rice and adding more tiers and heaping them with rice and putting something symbolical on the top, the usual method is that one lifts it up in one’s hands and recites various mantras and various verses expressive of one’s offering up of the entire universe to the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha. And the whole thing of course has to be done one hundred thousand times! Incidentally, I must interpose here just a little comment that amongst the slides which I hope we shall be showing at the end of the or after the last lecture in the series, there will be one slide showing a simple form, a simple version of this mandala model, complete with rice and so on, so you’ll know exactly what it looks like.

Now the meaning of the practice. The one who is practising, the one who is doing the four mula yogas, wishes to gain enlightenment, Buddhahood, for the sake of all living beings. In other words he wishes, or she wishes, to become a Buddha. Well for this purpose an enormous accumulation of what is technically called merit or punya is necessary. And it’s axiomatic for Buddhism in all its forms that merit or punya is gained by dana, by giving, by generosity. This is in a way the basic, the cardinal Buddhist virtue, to give.

And this is one of the most wonderful features of life in Buddhist countries that everybody is so generous, they so readily share with you whatever they’ve got. If you visit someone, if you go to their home, at once you must be offered at least tea, if possible a whole meal, or some little gift, and if you go to see someone you must take something along with you, not go empty-handed. So

this is a great characteristic of Buddhism everywhere, dana, because it’s a means to punya, spiritual merits and so on.

Now if it’s meritorious just to offer a cup of tea or a little money, or if it’s meritorious to give one’s time or one’s energy, or if it’s meritorious say to offer a monastery or a temple, how much meritorious it would be to offer the whole universe? To offer absolutely everything? Well how much merit you’d gain from that!

And of course Buddhism teaches, especially in the Mahayana form, that it’s the intention that counts. The sincere mental offering is the real offering. In all the religions of the world there are versions of the story of the widow’s might. It’s not what you give, it’s the will to give that counts. So this is the way in which meritis accumulated. You mentally, with sincerity, with

devotion, you offer up the whole universe, a symbolical representation of the whole material world, in all its levels, all its layers, all its aspects, all its features, with all its treasures, and you try to develop the genuine spiritual feeling that if everything was yours, you’d offer it all to the Buddha, you’d offer it all to the Dharma, you’d offer it all to the Sangha. And in this way you accumulate spiritual merits.

Of course it is very important that this shouldn’t become a formula or a formality. One must genuinely feel that on offering the mandala you are offering up absolutely everything, that even if you became the richest man in the world, no need to mention names, but even if you became the richest man in the world, you’d devote it all to Buddhism, all to the Buddha, all to the Dharma, all to the Sangha, or even if you became master of the whole universe, well you would be able to think of nothing better to do with it

than offering it to the Buddha. Some Buddhist kings in the past in a very grandiose way actually offered their whole kingdom to the Buddha. Sometimes they’ve taken it back the next day, but that’s neither here nor there! But you get the feeling, you get the idea, this will to give, this will to surrender, the will to offer up. This is what the Offering of the Mandala really signifies or really symbolises.

So these are the Four Foundation Yogas. And as I said at the beginning they’re the basis of Tibetan spiritual practice. And unless we know them, we really understand nothing, or very little at best, of Tibetan spiritual life. As I’ve said they’re usually regarded as preparatory to the practice of the Vajrayana as a whole, the practice of Tantric Buddhism, but it is also said that any

one of them, whether the Going For Refuge and Prostration, or the Development of the Bodhichitta, or the practice of the Vajrasattva visualisation and mantra recitation, or the Offering of the Mandala, any one of them if thoroughly practised, deeply and sincerely and continuously practised, will bring one very, very near to enlightenment, especially it is said the third mula yoga, the Meditation and Mantra Recitation of Vajrasattva.

Perhaps it isn’t necessary for me to say anything more. In this connection perhaps all that remains is for us to practise. And even if we confine ourselves to the content of this lecture, we’ll probably have enough to keep us busy for quite a long time to come.