Can There Be a Cultural History of Meditation? With Special Reference to India

by Johannes Bronkhorst

In these blessed days, interested readers can easily inform themselves about the history of a variety of cultural items. Recent years have seen the publication of books with titles such as A History of God (Karen Armstrong, 1993), A History of the Devil (Gerald Messadie, 1996), A History of Heaven (Jeffrey Burton Russell, 1997), The History of Hell (Alice K. Turner, 1993). These are cultural histories, because these authors and most of their readers will agree that God, Heaven, Hell and the Devil are cultural constructs, with no existence outside of culture.

There are other items, however, that are not only cultural. One might, for example, study the so-called historical supernovae, exploding stars whose first appearances have been recorded in historical documents. The most famous historical supernova is the one that was to give rise to the Crab Nebula; well known to contemporary astronomers, it was observed in 1054 CE by their predecessors

in China.1 These and many other historical supernovae might be treated in a cultural history of supernovae. Such a study would provide information about the way people in different cultures reacted to this or that supernova. The Chinese reaction, to take an example, might be altogether different from the way, say, medieval Arab astronomers and astrologers reacted to the same phenomenon. Such a cultural history might bring to light various ways in which different cultures (or the same culture at different times) interpreted these heavenly phenomena. But behind the cultural differences there would be objective, not culturally determined facts, viz., the supernovae. Supernovae are not, or rather, not only, cultural constructs, and the cultural constructs that are created around them have a core that cannot be taken to be on a par with God, Heaven, Hell, and the Devil, which are.

If we try to study the cultural history of meditation, we have to determine whether meditation is to be categorized with God, Heaven, Hell and the Devil, or rather with historical supernovae. Is there, independently of the cultural context, such a thing as meditation, or meditational states? If we think there is, our study is going to take an altogether different shape than when we think there is not. If we think that there are no such things as meditation and meditational states, our textual sources are the beginning and the end of our enquiry. Just as in the case of the History of God or the History of Heaven we do not ask what God or Heaven are really like, our history of meditation, too, will then proceed unencumbered by such questions. If we do, however, accept that meditation is something quite independent of the way it is interpreted within different cultures, we will wish to know what it is. The comparison with the historical supernovae is valid in this case: Our Chinese, Arabic, or any other sources take on a different dimension once we know that they refer to an objective event that can be confirmed by modern astronomical methods. I suspect that the editor of this book tries to get around this difficulty by emphasizing meditative practice. A document he distributed in preparation of a conference on the issue repeatedly speaks

1 For a translation of the Chinese and Japanese sources related to the Crab Nebula, see Clark and Stephenson 1977: 140 ff., and Duyvendak 1942 about meditative practice and, more in particular, about the relationship between meditative practice and interpretation. This is a clever move because meditative practice is something that outsiders can see and describe, but it is one that I find, in the end, to be unsatisfactory. It is like concentrating on the practice of our ancient astronomers of looking into the sky, while omitting to ask what they were looking at. Meditational practice derives at least part, and more probably the whole, of its raison d'etre from the subjective states it gives rise to, and serious research has to face up to this. Meditational experience (and in some cases suppression of experience) is that which, in our comparison, corresponds to supernovae; without it our study of meditation runs the risk of becoming an empty enumeration of the ways in which certain people in certain cultures sometimes sit down with their eyes closed, and more such uninformative information.

Certain readers, while agreeing with my emphasis on experience rather than practice, will object to my comparison with historical supernovae and consider it simplistic. Meditational states cannot be compared with supernovae; they are altogether different "things". One cannot separate meditational states from the culture in which they are evoked and experienced.

I am aware of these objections, and I grant that they oblige us to be slightly more precise. We can distinguish not just two, but three positions:

1 . Like supernovae, meditational states are there quite independently of their cultural interpretation.

2. Like God and Heaven, there are no meditational states. For reasons that remain obscure, certain cultures talk about these, in the end, nonexistent entities.

3. There are meditational states, but they are even in theory inseparable from their cultural context.

I have the impression that many scholars of mysticism and meditation - which, as the editor of this book observes, "are not the same thing, [but] raise many of the same issues" - may be inclined to accept the third position. Personally, I am willing to consider the possibility that meditational states and the cultural context to which they belong are hard to separate in practice. It seems to me, however, that if one is not even ready to consider that they may be separable in theory, the very basis of a project like ours would collapse. If the two are indeed inseparable even in theory, there is no way of determining whether, say, a Daoist in China and a Christian monk in Greece are both meditating; or rather, one might feel compelled to say that these people are each engaged in practices characteristic of their own cultures, with no essential features in common apart from, at best, some superficial and potentially misleading similarities. A cultural history of meditation that covers more than one single culture would in that case be difficult, if not impossible.

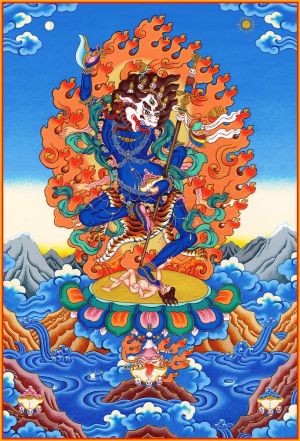

There is another point that has to be made. Brain studies of meditators have become quite popular of late. This started, if I am not mistaken, with Transcendental Meditation. Now Tibetan Buddhist monks appear to be all the rage. Reports indicate that these studies yield results. It is, of course, possible that more extensive neurological studies will bring to light differences in meditators from different cultures, but our first reaction would be to think that this is indicative of different meditational techniques that were being used, not that different cultures were involved. We might, for example, find consistent differences in brain patterns in the case of Transcendental Meditation and Tibetan Buddhist meditation. We would be more surprised if it turned out that Westerners who had learned to meditate from Tibetan Buddhist monks showed consistently different brain patterns from their teachers, and that in their essential features. I wonder whether brain researchers have ever even considered this possibility, yet this is what we would expect if meditational states were to be inseparable from culture.

To sum up, I am most willing to consider that there are different meditational states. It is even possible that some meditational states are more frequently practiced in one culture than in another. However, the claim that meditational states are even in theory insepara

ble from their cultural context seems, for the time being, baseless and not fruitful.

This does not mean that the interpretation of meditational states will be independent of the culture in which they are experienced. It seems likely that in this respect, meditational states may be similar to mystical states (which they may also resemble in other respects): a Christian mystic is likely to experience the presence of a Christian sacred entity (God, the Holy Spirit, etc.), where a Hindu mystic may experience a Hindu sacred entity (Brahman, etc.). This, however, is a matter of cultural interpretation. At any rate, this seems to me the most sensible assumption to make if we wish to make progress in this project.

The answer to the question I raised earlier is therefore: Meditational states are rather more like supernovae than like God, Heaven, the Devil and Hell, in that they have an independent reality which culture has not created. Culture can, and will, interpret these states. A cultural history of meditation will therefore comprise a history of cultural interpretations of states that are, in their core, not culturally determined. It may comprise more than only this, however. I have argued that at least some of the presentations of meditation which we find in our texts and perhaps elsewhere are interpretations of meditational states that have some kind of existence of their own; yet this may not be true of all of them. There may be presentations of meditation that are not linked to any meditational states whatsoever. This is more than a mere theoretical possibility. I will discuss some examples taken from the Indian tradition, where this can be shown (or at the very least argued) to be the case.

specific associations between meditative techniques and cultural and religious institutions."

My first example will be taken from Jainism, due to the fact that it presents an extreme and most curious example of a cultural interpretation of meditational states that were not meditational states at all.

Canonical classificatory texts of the Svetambara Jaina canon enumerated everything that can be covered by the termjhiifia (Skt. dhyiina). This is the term generally used in connection with meditation, primarily in Buddhism yet also in Jainism, but in the early Jaina texts it also covers other forms of mental activity, such as 'thinking' . By collecting together all that can be covered by this term, these classificatory texts arrived at an enumeration of four types of dhyiina: (i) afflicted (atta I Skt. iirta), (ii) wrathful (rodda I

Skt. raudra), (iii) pious (dhamma 4 I Skt. dharmya), (iv) pure (sukka I Skt. sukla ).

For reasons unknown to us, these four kinds of dhyiina came to be looked upon as four types of meditation, enumerated among the different kinds of inner asceticism; so Viyahapawatti 25.7.217, 237 f./580, 600 f. and Uvavaiya section 30. The later tradition, when it looked for canonical guidance regarding meditation, was henceforth confronted with a list of four kinds of 'meditation', only the last one of which (viz. 'pure meditation'), should properly be regarded as such.

But things did not stop there. The later Jaina tradition adopted the position that 'pure meditation' is inaccessible in the present age (in this world). Sometimes this is stated explicitly, as, for example, in Hemacandra's Yogasiistra. More often it is expressed by saying that one has to know the Purvas in order to reach the first two stages of pure meditation. The fourteen Purvas once constituted the twelfth Aii.ga of the Jaina canon. They were lost at an early date.

Already the Tattvartha Sutra (9.40; see Bronkhorst, 1 985a: 176, 179 f.) states that knowledge of the Purvas is a precondition for entering pure meditation. This means that already in the time be tween 150 and 350 C.E. pure meditation was considered as no longer attainable in this world.

The reasons why 'pure meditation' came to be looked upon as no longer attainable in this world seem clear. It appears to be the almost unavoidable consequence of the gradual exaltation in the course of time of the Jina, and of the state of liberation preached by him. A comparable development took place in Buddhism where early, already superhuman qualities came to be ascribed to Arhats (see Bareau, 1957) and release was postponed to a next life.7 Whatever the reason may be as to why 'pure meditation' was excluded from actual practice in Jainism, it is clear that all existing practice henceforth had to be assimilated into the descriptions of 'pious meditation'. ('Afflicted dhyana' and 'wrathful dhyana' were, very understandably, considered bad forms of meditation.) This means that two historical developments - (i) the addition of 'pious meditation' under the heading 'meditation' (dhyana); (ii) the exclusion of 'pure meditation' from it - left later meditators with a canonical 'description of meditation' which was never intended for such a purpose.

One can easily imagine countless numbers of Jaina monks in the course of history who seriously and determinedly tried to meditate in accordance with the guidelines handed down in their canonical texts. They did not know, as we do now, that these guidelines were not guidelines; that their meditational practices could not correspond to their canonical muster because the canonical muster never had anything to do with meditation. Some Jainas, presumably only the most determined and enterprising, abandoned the effort and looked for guidance elsewhere, outside the Jaina tradition. There are a number of known cases where Jainas introduced other

7 In later times the reason adduced for this was often that liberation would become possible after rebirth in the time of a future Buddha, esp. Maitreya; see Kloppenborg, 1982: 47. 8 This is not to say that the canonical description of 'pure meditation' is very satisfactory. Hemacandra (Yogasastra 1 1. 1 1), for example, rightly points out that the last two stages of 'pure meditation' concern the body rather than the mind. forms of meditation into the J aina tradition, and along with them, of course, the cultural interpretations that accompanied those other forms of meditation. Yet those who were less enterprising, or more traditional, may have gone on trying to practice meditation following guidelines that were not based on meditative experience of any sort whatsoever.

The case of Buddhism is less extreme, and also less bizarre, than that of Jainism. Buddhism too, however, preserved canonical guidelines for the meditating monks which were a scholastic combination of two altogether different practices. The well-known list of nine meditational states is, as I have argued elsewhere, a construction composed of two shorter lists. The two kinds of meditation that find expression in these two shorter lists are quite different from each other and pursue different goals.

One of these shorter lists is the list of four dhyiinas; the other one the list of the Four Formless States (iirupya, Pa arupa), to which sometimes a fifth is added, the Cessation of Ideation and Feeling (sal'J1}niivedayitanirodha). The second of these two lists aims at the suppression of all mental activities. The former has a different goal, which I have called "the mystical dimension" for want of a better word. The four dhyiinas seek to attain an ever deeper "mystical" state, whereas the Four Formless States only aim at suppressing mental activities.

Later Buddhist meditators, like their Jaina confreres, were therefore confronted with confusing canonical guidelines. Those who did meditate made no doubt the best of the situation; some may have decided that the canonical guidelines were of only limited use. However, to my knowledge Buddhist literature never abandoned them. The result is that the philologist who tries to study the cultural history of meditation in India appears to be confronted with data whose connection with real meditation is artificial at best. 9

In these two cases it can be shown, or at least argued, that the descriptions of meditation do not correspond, at least not directly, to real meditational states or to real sequences of meditational states. There may be other cases where our textual material is not sufficient enough to determine whether we are confronted with a scholastic construction rather than a description or interpretation of meditational states. This, of course, makes a cultural history of meditation very difficult.

Where does all this leave us? I stated earlier that a cultural history of meditation must be a history of cultural interpretations of states that are, in their core, not culturally determined. The examples I have discussed show that some of the presumed cultural manifestations of meditational states are nothing of the kind, and may indeed lead us astray. To use the comparison with supernovae: some of the recorded "supernovae" may not correspond to real supernovae; some of the so-called meditational states recorded in religious texts may not correspond to any real meditational states. In some cases, as in the ones just discussed, mere philological diligence may bring to light that there are no meditational states or sequences of meditational states behind certain claims of that na ture. In other cases, philology may not be sufficient to render us this service. In those other cases we would like to know more about the "real supernovae, i.e. the real meditational states that hide behind their cultural manifestations. In other words, just as the historian of the so-called historical supernovae needs to know something about real supernovae, in the same way the author of a cultural history of meditation needs to know something about what meditational states really are.

It seems that the editor of this book agrees with this. He speaks, for example, about the "the difficult question of whether or not su perficially similar ideas in different cultural contexts still point to the same reality, or whether superficially disparate ideas really point to different phenomena, or are just surface manifestations of the same underlying unity." He seems to think that a solution has to be reached, and can be reached, by way of an in-depth study of the different sources of information, including texts that describe medi tative practices, material culture and visual art, and present-day information about meditation techniques. In other words, he wishes to know what meditational states really are, and he proposes various methods of getting there.

He may overlook an important factor, however, which he might not have missed if he had thought of the comparison with historical supernovae. In order to understand historical supernovae we need to know all we can about the cultures in which the relevant observations were made. In order to understand real supernovae these historical records are by far not enough, and are of relatively minor importance in comparison to astronomy. Modern astronomy tells us more about real supernovae - what they are, why they exist, how they "work", etc. - than any amount of historical records. In the same way, in order to understand real meditational states, and not just what people through the ages have said and thought about them, we need the equivalent of astronomy for human experience and human functioning in general. We need a theory of how humans function, of how meditational and other states come about and are related to other experiences and practices.

Unfortunately there is nothing corresponding to astronomy in relation to the mental functioning of human beings. Yet this is what we need if we wish to make headway.

It is not new to the reader that psychology and the other "human sciences" have not been very successful thus far in presenting us with a general theory of human functioning, and indeed the reader may, like myself, have the impression that the aim of producing such a general theory is not on their list of priorities. Out of frustration, I have myself tried to work out the skeleton of such a theory in my recent book Absorption: Two Studies of Human Nature (2012). I will take this theory as my point of departure in what will follow.

One of the features of the theory presented in Bronkhorst (2012) is that it presents the human mind as having two levels of cognition: the non-symbolic and the symbolic. Of these two, the nonsymbolic level of cognition is fundamental, whereas the symbolic

level of cognition is superimposed onto it, largely as a result of the acquisition of language at a young age. The overall combined cognition resulting from these two levels is deeply colored by the multiple associations "added" by the symbolic level of cognition. Normal cognition cannot therefore be directed at an object, say a telephone, without an implicit awareness of its purpose, its relationship to other objects etc.; in short, its place in the world. Nonsymbolic cognition does no such thing, but is normally "veiled" by symbolic cognition.

However, non-symbolic cognition can, in exceptional circumstances (and more easily for some individuals than for others), rid itself either wholly or in part of the veil of symbolic cognition. This may happen spontaneously in psychotics and mystics, but also, to at least some extent, through the voluntary application of certain techniques. These techniques may vary greatly, but they will have one thing in common: the special form of concentration I call absorption (see below). Absorption, just as ordinary concentration does to a lesser degree, reduces the number of associations (most of them subliminal). It follows that, if the degree of absorption is high enough, this will have cognitive consequences: experience of the world will be different, and will be accompanied by the conviction that this "different" reality is more real than that of the world ordinarily experienced. It will indeed be more real in the sense that the "veil" that normally separates us from the objects of cognition will have been removed, or at least thinned, resulting in less that separates us from them.

We might, provisionally, call "meditation" all those techniques that "thin" the "veil" that is due to symbolic cognition. This kind of meditation, whatever precise form it takes, will then be characterized by absorption and, if the absorption is deep enough, will have an effect on cognition. However, there is more. Absorption has a further effect. Deep absorption gives rise to feelings of bliss. This is an effect quite different from the one mentioned earlier - modified cognition - and is due to a different mechanism, although this is not the occasion to describe that mechanism. Its consequence is all the more interesting in the present context, for it adds a further characteristic to what we provisionally call "meditation". This kind of meditation is characterized by absorption, by modified cognition (access to a "higher reality"), and by bliss.

Let me now say more about absorption. Absorption is a form of concentration, but is not quite like the concentration one experiences within daily life. It is accompanied by, and in a way based upon, a deep relaxation of body and mind. Due to such deep relaxation of body and mind, absorption can reach depths that ordinary concentration cannot. Some people attain absorption without special techniques (we tend to call them mystics), some others do so with the help of certain techniques, and most of us do not normally attain degrees of absorption of any depth in spite of all our efforts.

A clear understanding of the way the word meditation is used here will allow us to distinguish between different practices that are indiscriminately called meditation in scholarly literature. Before we pursue our reflections about meditation, it is worthwhile to point out that the three features identified above - absorption, special cognition and bliss - recur in many descriptions of mystic states. This confirms that the kind of meditation we are concentrating on has these features in common with mysticism, and can in a way be looked upon as self-induced mysticism. Let us refer to this kind of meditation as meditation.

Meditation1 corresponds to one of the two types of meditation I distinguished in my book The Two Traditions of Meditation in Ancient India (1993a). It is the meditation introduced in India by Buddhism. Absorption and bliss are essential features of this kind of meditation; the cognitive effect is, in the early Buddhist texts, to some extent overshadowed by the emphasis laid on the cognitive realization ("liberating insight") associated with the final and definitive transformation that can be brought about by the practitioner while in the deepest state of absorption.

More recent texts, both within and without the Buddhist tradition, emphasize the cognition without "conceptual constructs" that is accessible to those who practice this kind of medit:ition, Th ter.:r.s used 3.re vikalpa. and kalpanfi, and the texts often point out that these conceptual constructs are the result of verbal knowledge. This, of course, looks very much like another way of saying what was observed above, viz., that the symbolic level of cognition is due, wholly or in part, to the acquisition of language.

It may be noted in passing that the transformation referred to in the early Buddhist texts is not presented as a result of meditation, or of absorption for that matter, but rather as the result of a procedure undertaken while in deepest absorption.

Meditation1 distinguishes itself, often explicitly and in critical terms, from what we may call meditation2; both are designated by the same term dhyiina in Indian texts. Meditation2 is quite different from meditationi, and should strictly speaking not be called medi tation at all, or at any rate not in the way in which we have chosen to use this term. Meditation2, unlike meditationi, is not characterized by absorption, bliss and cognitive effects. It rather has its place in a wider belief system in which the suppression of all activity is a sine qua non for escaping the effects of one's deeds, i.e. escaping from karmic retribution.

Meditation has its place in a number of early movements different from Buddhism that were intent on such an escape, among them Jainism. Notably, the word Yoga in the early texts covers practices that are of this nature. In terms of the theory proposed in Bronkhorst (2012), it appears that absorption plays no role in meditation2, mainly because it is not based upon a profound relaxation of body and mind. Indeed, its forcible, violent nature is not only clear from the descriptions provided by texts close to its practitioners, but also from the criticism directed at it in Buddhist texts that do not sympathize. It is here we find, for example, the method of closing the teeth and pressing the palate with the tongue in order to restrain thought, both in texts that criticize and those that promulgate this practice.

Conclusion

It follows from the above that not all the practices that go by the name meditation (in India: dhyiina, etc.) necessarily have much, or indeed anything, in common. At the same time it is reasonable to assume that practices that on the surface have nothing in common may yet belong together. The main characteristics of meditationi, for example - absorption, bliss, cognitive effects - may result from a number of superficially different practices such as yogic concentration, fixing the mind on God, reciting texts and rhythmic movements. Even completely "non-religious" practices (say, surfing) may bring about states of absorption deep enough to create bliss, though normally with no recognizable cognitive effects.

Seen in this way, the study of meditation takes us into a realm that is not limited to meditational practice. We are here confronted with an aspect of mental functioning that also finds expression elsewhere. This is not surprising, because we are dealing in all these domains with the same human mind. A theoretical understanding of the functioning of the human mind is our only hope to ever make sense of the variety of practices that we tend to assemble under the banner of "meditation".

Words for "Meditation" in Classical Yoga and Early Buddhism Jens Braarvig

Even though "meditation" often may be quite undefined as used in a modem, or "Western" context, it is definitely a much employed word, designating a huge array of activities concerned with finding peace of mind, mental health and ultimately self-development. As such, it refers to an item which is understood to be a personal and individual activity, an activity taught and collectively performed within organizations, usually with a particular ideological background religious or otherwise.

This activity is often referred to as a method or type of therapy in its more secular forms, while in a religious setting it is more frequently referred to as a "way of spiritual development". These organizations typically have leaders; expert teachers who, in their religious forms, are often venerated as superior, at least in the art of meditation and in the context of certain narratives, seen as in possession of a trans-worldly perspective. In its secular forms, "meditation" becomes a commodity which can be bought for a certain sum, as a a particular economical routine with therapeutic aims, while in the religious setting it also coincides with the peculiarities of religious economy and rhetoric. The word "meditation" does, however, function well in modern languages as a collective designation of mental disciplines, most of them derived from Indian and Buddhist traditions. From such starting points the word has penetrated into general usage within modem languages, and the practices designated with the word have suffused substantial parts of modem religious life.

Thus, though meditation in some forms may be found in other cultures, even those of Europe and the Middle East, most of the concepts and rhetoric of modem forms of meditation seem to be derived from an Indian background, generally through the agencies and activities of Theosophy and various Buddhists sects; firstly the Pali tradition, then Zen and Tibetan meditation ideologies within the Tibetan Diaspora - not to mention the multiplicity of meditation systems founded on the classical "Hindu" philosophies and sects, and even the academic scholarly work on these traditions. Thus, during the last hundred to hundred and fifty years, the activity of "meditation" has seen a steep increase in the modem context, accompanied with a steadily increasing terminology in Western languages. This terminology is probably, at least historically, sufficiently connected with an Indian background to make it meaningful to delve into the plethora of Indian meditation concepts in terms of trying to understand meditation as a phenomenon, be it "Eastern" or "Western", and in trying to find out what meditation is, or might be.

The above, very general, description of meditation would most likely also hold strong for the Indian traditions of meditation, but judging from the classical literature of India, the belief in meditation as the solution to nearly everything, be it worldly aims or the ultimate liberation, must be said to be very prevalent, much more so than in other traditions. It is no surprise, then, that the Sanskrit language displays an enormous terminology connected with that activity, and that the various words referring to aspects of what we in general may term "meditation" have different meanings in differing contexts and ideological systems.

In the following pages, therefore, we will scratch the surface of Indian thinking about "meditation" and gain a brief overview on some much-used meditation words and how they acquire specialized meanings in certain contexts. Emphasis will be put on the classical Yoga system and the meditation words of the Buddhist Abhidharma, as these may be said to give the historical premises from which the terminological complexity has grown. One can indeed be surprised by the grandiose terminology connected with what may seem to be a fairly simple human behaviour, namely sitting in this or that way with eyes closed or almost closed, and not falling asleep.

I will thus relate to the words of "meditation" in two Indian contexts which have a rich terminology of meditation practice, viz., the "Classical Yoga" as described in Patafijali's Yogasfitras and in the traditional system of meditation in Buddhism. It is characterized by its progress from the sensual realms of kamaloka to the form world of rfipadhiitu, through this sphere of existence into the formless world of iirfipyadhiitu, resulting in the kind of meditation which transcends the world of suffering and provides the final liberation from it. The terminology of this system is fairly universal throughout Buddhism, though some of its importance has been lost in the traditions of the Mahayana.

The meditation words of Yoga are often shared with those of Buddhism, but having been placed into other semantic fields they receive other definitions and meanings, meanings which are also shared by other treatises in the same meditation tradition as the Yogasutras. One can find, for example, the complete set of technical terms of the a:f{iingayoga in the Bhagavadgfta.

Clearly these two (I say two for the sake of simplicity) traditions of meditation in India have a lot in common, they have grown out of the common background of the Upani$ads and the origin of meditational ascetism in India in the middle of the last millennium B.C. Thus the terminologies are similar, but not identical. As we will see, the flavour of the various words for meditation are, in their context of the afore-mentioned traditions, different, and their meanings may vary. To some extent this is influenced by the underlying philosophies.

Those of yoga build upon the principle of the eternal and ineffable Self, the clfman, and its near-synonyms, puruf!a: "inner man", jfva: "soul", or "the life principle", draf!tr: "the witness" or "onlooker". This has, to some extent, created a meditation terminology differing from the more nihilistic principles of Buddhism, negating the Upanifjadic Self with its selflessness principle, the anatman, and the principle of emptiness, siinyata, which is a key concept in the Mahayana settings. Even though the philosophical disagreements between the two main traditions of Indian thinking are fairly great and a few variations have developed within the field of meditational terminology, it was always generally agreed upon that meditation and concentration are the means to health, success and liberation from suffering.

Such outcomes result from the practice of meditation, with its origin in the sramm:ia, or ascetic, milieus in this formative period of Indian spiritual life. To put it simply, every tradition usually formulates its creeds in its own language garb - like every trade formulates its brand - and this is also the case with Indian meditation traditions and their priests and meditation specialists. Thus the tradition of yoga, as formulated in the Yogasiitras, has words and terminology which are somewhat different from the Buddhist traditions as set forth in the Pali canon, though the two traditions share the emphasis on meditation and the practice of yoga as the way, indeed the only way, to liberation and so forth. Only Mahayana Buddhism, even if it has much of the same terminology of the afore-mentioned form of Buddhism, places less emphasis on meditation as a way of sitting, a method, or something to be practiced in solitude.

Thus it promulgates the view that a bodhisattva should always be in a state of meditation, mindfulness or concentration, whatever he is doing and, as per the ideal in the Bhagavadgzta, emphasizes social virtues and ethical action as a way to human perfection. This view of meditation, which is somewhat critical of the ascetic and solitary ideals of yoga and early Buddhism, may have comparatively reduced the importance of meditation in this tradition; yet when we look at the Mahayana traditions historically, we still find that meditation is considered to be very important.

In this way, and on a general level, Classical Yoga definitely has much in common with the traditional Buddhist goals of meditation, even though the ontological bases of iitmanlpuru$a and the principle of aniitman may be quite opposite. Thus yoga aims at placing the "seer in its own form" (tadii dra$fub svarupe 'vasthiinam, I,3) and isolating the "self', "inner man", or the "principle of seeing", from everything else (tadabhiiviit smrzyogiibhiivo hiina1'{l taddrseb kaivalyam, II,25) and, as expressed in the final verse of the work: "The suspension of the qualities as being devoid of aims for the inner man is called isolation" (puru$iirthasunyiinii1'{l gw;iinii1'{l pratiprasavab kaivalyam, IV,34) .

And: "The cause to be done away with is the connection between the seer and the seen" (dra$frdrsyayob sa1'{lyogo heyahetub, II,17). Thus defined, the goal of yoga, which is brought about in part by bodily discipline, but most of all by mental discipline - which indeed is also true of Buddhism - is very similar to the goal of Buddhism, namely to minimize and get rid of the mens, the mind itself, as set out in Yogasutra I,2: "The effort [in question brings about] the cessation of mental activity" (yogas cittavrttinirodhab, I,2). An effort of concentration with the aim to get rid of the psyche itself is definitely quite a radical psychology, but it is shared by both contexts. When one has rid themselves of all thinking, or of that which is "seen" by the eternal "seer", the Yogasutra would have this to be what could probably be translated as absolute concentration.

This is namely the samiidhi, in which concentration is somehow thought of as being its own object of concentration and thus the "seer" itself and, having no support or "seed", is considered nirbfja (I,5 1). It is also the result of a type of knowledge, prajnii, which arises from the lucid balance that occurs within when all mental activity and reflective thinking has ceased, and when the concentration is, as it is phrased, nirviciira (I,46-50).

The idea that concentration can exist without anything to concentrate on, must be connected with the idea that "what" is performing the act of concentration, usually in Yogasutra called "the seer" (equivalent with puru$a, iitman, etc.), is the only entity left when everything else is omitted, nothing but that which is left, so to say. This assumption, of course, is built on the ontology shared by Yoga and Sii1'{lkhya, even by Vedanta and other systems postulating an eternal self-principle.

There is also sabf}ab samiidhib (I,46 and preceding verses), the type of concentration that has an object and is connected with vitarka and vicara, expressions used for intellectual activity and investigation. Perhaps "introspection" or "reflection" might be an apt translation here for vicara, and "investigation" for vitarka. In this state, concentration is also called samapatti, etymologically meaning "coming together", and then "attainment". One should not fail to note that both the words samadhi and samapatti are connected with the concept of joining or keeping something together, loosely connected with yoga. "Joining" presumably indicates the collecting of diversified thoughts into a concentrated state, indeed the words "concentration" and "focusing" also have some of the same import.

The usual Buddhist definition of samadhi is likewise in accordance with these meanings, namely, that the "mind is directed towards one point" ( cittasyaikagrata), a definition which is shared by the Yogasutras: "The transformation of thought by means of concentration is the end of being diverted among all kinds of objects, and the production of one-pointedness" (sarvarthataikagratayol:z kayodayau cittasya samadhiparb:zamal:z, III, 1 1 ). It is of course not at all surprising that the Buddhist views on mental discipline are very similar to those of the yoga schools; indeed they grew from the same fertile intellectual ground and have influenced each other throughout the course of their development, and, being part of the same Sanskrit world of concepts, certainly the semantics of these were naturally shared.

It seems now that the mentioned sabija forms of concentration are only connected with the necessary evils of intellectual life, as with that of logic, for example -tarka does indeed mean logic in general, and forms of mental activity are also the pramafla, or "means of knowledge". This is also in-tune with the Buddhist tradition, which developed logic with a definite sophistication, but always looked upon it as inferior to the experience of the "reality", or the "divine".

Thus in the Yogasutras these kinds of mental activity are mentioned, but they are rather to be done away with for the sake of the prajna, of the absolutely concentrated state of samadhi, where the essential state of all-knowledge is reached.

This kind of concentration, however, is reached rather by the following methods, eight in total: 1) the control of one's ethical behaviour, 2) one's self-control, then by 3) the correct postures, and 4) control of one's breathing, accompanied by 5) drawing the senses back from their outer objects. One cannot help but notice the strong emphasis on control and effort required to reach the three last, most essential members of the eight, namely those of meditation proper which loosely may be translated as: 6) "keeping focus", 7) "meditation" and 8) "concentration". (yamani

yamiisanapriif!iiyiimapratyiihiiradhiiraf!iidhyiinasamiidhayo '$fiiv angiini II,29 and explanations of the eight members in the following verses.) In so keeping oneself focused on an object, dhiiraf!ii, is defined as "binding one's thought to a place" (de8abandhas cittasya dhiiraflii III, 1) and, as a more intense form of mental discipline, meditation is defined as continuous single-mindedness directed toward an object (tatra pratyayaikatiinatii dhyiinam III,3) while samiidhi, the final member of the afore-mentioned eight and ultimate aim of yoga, takes over as being the only object of concentration itself: "Concentration is the shining forth of only that only object, as empty of any own form" (tad eviirthamiitranirbhiisarrz svariipasiinya iva samiidhifl III,3). From this also shines forth the light of knowledge (tadjayiit prajniilokafl III,5), the knowledge that the seer and the seen are definitely different, and thus the isolation of the seer takes place. On the path to the final consummation of meditation, however, all kinds of knowledge and powers are believed to be attained, as is the belief in all Indian meditation cultures.

The grand vision of the Yogasiitras is even more extended in the Buddhist context, as the Buddhists in addition correlated their meditation experiences with a cosmological setting: The cosmos is seen as really no more than the states of consciousness as experienced by those living in the corresponding world-spheres, thus reaching subtle and thoughtless states of mind entails rising to more subtle world-spheres in the Buddhist cosmological system, ultimately transcending the cosmos altogether. At that point one reaches nirviifla after death, or in the meditative state of vajropmasamiidhi, "the concentration which is like a diamond", "touching nirviifla while still in the body", also called nirodhasamiipatti, "the attainment of cessation". As in many religions or movements built upon an ideology, however, the conceptual systems are not complete from the beginning. Thus we find in what we can construct as early Buddhism many terms for meditation and its cognates, but not necessarily as yet completely systematized as what we find in the later systematization and scholasticism of the Abhidharma.

The optimism of the Indian culture of meditation at the time of early Buddhism is evident in the satipafthanasutta (and all its Sanskrit counterparts), where the concept of satipatthana, in Pali, or smrtyupasthana in Sanskrit, is explained as the only way for living beings to be purified, to rid themselves of their suffering and depression and reach nirvilt:za ( ekiiyano ayal?1 bhikkhave maggo sattiinal'f1 visuddiyii sokapariddaviinaJ?1 samatikkamiiya dukkhadomanassiinaJ?1 atthagamiiya nayassa adigamaya nibbanassa sacchikiriyiiya - yadidal?1 cattiiro satipatthiinii. §2).

The word satipatthana is usually translated today as "mindfulness" - indeed a very apt translation, which has been integrated into a great number of modern religious and therapeutic settings. "Awareness " is another common English equivalent of the word. The word upasthiina, meaning something like "standing by", has never been properly understood in the context concerned, it is often translated as "presence of', etc. The sati, or Sanskrit smrti, is however one of the great words in the Sanskrit vocabulary, basically meaning "memory" - it also denotes what every Indian of the upper classes had to remember, namely the tradition of the interpretations of the sruti, that which has been heard from the gods.

The enormous emphasis in Indian tradition on remembering has influenced a culture of mnemotechnics and concentration and thus also a culture of meditation, which indeed may be said to be a kind of "remembering". This dichotomy is found in the Buddhist use of the word smrti, which on the one side is to remember the Buddhist teachings, but then also refers to remembering one's earlier lives since "beginningless time" - also a fruit of the meditational practice, according to the theory. Yet most of all sati/smrti denotes the practice of what may be said to be remembering the present (also a projection of the past, according to Buddhism), and thus being mindful, aware of what one is in every moment.

A long list of what to be aware of (and what oneself is, then) is given in the satipafthiinasutta, classified under the categories body, feelings, mind and states of consciousness (dhamma). Classed under body-mindfulness one can find the popular "walking meditation", along with awareness of other postures - somehow reminiscent of the body postures of Yoga, as is also the case with the awareness of breathing, reminiscent of the prcil:zayama of Yoga. The Buddhist canon even devotes a whole sutta to this, the Anapanasatisutta, which also, like Yoga, prescribes correct posture: Secluded place, crossed legs, straight back. It seems, though, that the Buddhist meditations are not regarded by their classical practitioners as so much a type of control as that of Yoga - all the kinds of nouns derived from the root yam, meaning "to control, are found in yogic terminology: yama, niyama, smrzyama, praftayama, etc. The idea of Buddhism seems rather to be that the peaceful reflection on feelings, thoughts and so forth, will eventually bring about their cessation simply by regarding them and then giving them up. Indeed, these two moments of "seeing" and then "giving up" the various states of mind are described at least in the later Abhidharma. Mindfulness therefore seems to be sufficient as the ekayano maggab - the one vehicle or way to enlightenment.

Two other concepts which also have found resonance in modern meditational "methods" or "types of meditation" are vipassana and samatha, or vipasyana and 8amatha in Sanskrit. These two words, which are poorly defined in the classical Buddhist literature, seem rather to be qualities of meditation, the first one meaning something like "insight (meditation)" (which it has often been translated as) or even "expanded vision", which would be a more etymological translation. The second concept is translated as "peacefulness".

With the developing tradition of scholasticism of Buddhism, however, the kinds of meditation so far mentioned, viz., satipatthana, vipassana and samatha, are placed in the preparatory stages of the carrier of the adept of Buddhist practice. In other words, they belong to the stage where the ridding oneself of passion, hate and delusion has not really started. This process of getting rid of the world, getting rid of all life and clinging to the painful states of the world - be they coarse or subtle, belonging to the world of passion or to the formless states - is described as increasingly subtle states of consciousness, and increasingly concentrated states where the objects of meditation are decreasingly complex, until the states of existence disappear altogether in order for vajroso pamasamadhi or nirodhasamapatti to happen, and subsequently nirva'}Ja after death.

These states are all together nine; one of the world of passion, in which humans, animals, spirits, hell inhabitants and the lower gods live, four of the world of form, and four of the formless world, the last eight being described rather as states of meditation than as places, which amounts to mostly identical concepts in many Indian cosmologies. This system is similar to Yoga in its being a transition from coarse to subtle states, from the pratyahara, through dhara'}Ja and dhyana, to the consummation of samadhi. In the Buddhist system, on the other hand, dhyana are the four meditative states of mind of the four worlds of form and samadhi, also here defined as concentration, is just a small part of the second dhyana, which is very different from Yoga where it is the summa of the development. The four states of meditation in the formless world of Buddhism, which are a higher and formless kind of concentration, are called samapatti, "attainments" (which in the terminology of the Yoga system is a lower form of conditioned concentration, connected with vitarka and vicara), "investigation" and "reflection", as has already been translated. The terms vitarka and vicara are similar in meaning in Yoga and in the Buddhist context. However, while the sati/smrti is of such importance in Buddhism as "mindfulness", etc., in Yoga it simply means plain memory. While dhara'}Ja has a technical meaning in the building up of samadhi in Yoga, in Buddhism this term, in the derived form dhara'}Jf, originally mostly meant "memory", though later it acquired the meaning of mnemotechnical mantra, used as an aid for meditation and the focus of concentration - this is of course aside from all the magical connotations of dhara'}Jf in Tantric Buddhism.

These terms are more on the cognitive side of meditation, and as such are on the vipasyana side in the traditional pair vipasyanii/samatha, where the latter is the part which refers to "inner peace of mind" (the two are supposed to be "joined in a team", yuganaddha). Another term in Buddhism, nidhyapti, etymologically related with dhyana, from the root dhyai- 'to think', is also a term between the state of concentration and knowledge side of meditation, best translated as "consideration". This touches upon a greater problem, namely what is the intellectual and knowledge part, and what is part which refers to the mental peace of meditation practices. In general, Buddhism tries to connect these epistemological phases, as in the case of vipassana and samatha, while Yoga tends to see concentration as also inclusive of the intellectual cognitive part: when the nirvikalpasamadhi, "concentration without thought-constructions" sets in, one also believes that one becomes omniscient and knows all phenomena in the world.

So let us here translate into English the Buddhist succession of more and more subtle meditational states; nine in number, corresponding to nine worlds, and ending with the nirodhasamapatti, the attainment of cessation, which is nirvafla after death and the aim of Buddhist meditation: "[The four meditations, dhyana, in the form-worlds, rupadhatu:] Here monks, when one has detached oneself of passion and bad moments of existence [that is, the world of passions], one behaves in the way of having attained the first state of meditation (jhiina, dhyana), which is characterized by investigation (vitarka) and reflection (vicara), and by happiness and pleasure born from being detached, after the appeasement of investigation and reflection one behaves in the way of having attained the second state of meditation, which because of inner clarity and one-pointedness of thought is characterized by absence of investigation and reflection, and by happiness and pleasure born from concentration (samadhi), being impassive as beyond any passion for happiness, being mindful and experiencing joy through one's body, and thus experiences what the saints see, and is impassive and mindful (satima, smrtiman) one behaves in the way of having attained the third state of meditation, which is characterized by absence of happiness, after giving up pleasure and after giving up suffering and indeed having gotten rid of elatedness and depression one behaves in the way of having attained the fourth state of meditation, which is characterized by neither suffering nor pleasure.

[The four attainments, samapatti, in the formless worlds, ariipyadhatu:] Having transcended completely all concepts of form, after the disappearance of conceptual hindrances, being without any mental activity concerned with conceptual diversity, one behaves in the way of having attained the field of experience of endlessness of space (akasananciiyatana, akasanantyayatana), where one experiences space as endless, having transcended completely the field of experience of endlessness of space, one behaves in the way of having attained field of experience of endlessness of consciousness

(vif'lfta1Jaftcayatana, vijnananant-yayatana), where one experiences consciousness as endless, having transcended completely the field of experience of endlessness of consciousness, one behaves in the way of having attained field of nothing in particular (akincannayatana, akirrzcanyayatana), where one experiences that there is nothing in particular, having transcended completely the field of experience of nothing in particular, one behaves in the way of having attained field of neither concept nor non-concept (nevasannanasannayatana, naivasarrzjnana-sarrzjnayatana), and having transcended completely the field of neither concept nor non-concept, one behaves in the way of having attained cessation (nirodha) as witnessed. These, monks, are the nine successive behaviours.

Idha bhikkhave vivicceva kamehi vivicca akusalehi dhammehi savitakkarrz savicararrz vivekajarrz pltisukharrz pathamarrz jhanarrz upasampa jja viharati. Vitakka vicaranarrz vupasama ajjhattarrz sampasadanarrz cetaso ekodibhavarrz avitakkarrz avicararrz samadhijarrz pltisukharrz dutiyarrz jhanarrz upasampajja viharati. Pltiya ca viraga upekkhako ca viharati. Sato ca sampajano sukhanca kayena patisarrzvedeti. Yantarrz ariya avikkhanti: upekkhako satima sukhaviharlti tarrz tatiyarrz jhanarrz upasampajja viharati. Sukhassa ca pahana dukkhassa ca pahana pubbeva somanassadomanassanarrz atthangama adukkhamasukharrz upekkhasatiparisuddhirrz catuttharrz jhanarrz upasampajja viharati.

Sabbaso rupasannanarrz samatikkama patighasannanarrz atthangama nanattasannanarrz amanasikara anatto akasoti akasanancayatanarrz upasampajja viharati. Sabbaso akasanancayatanarrz samatikkamma anattarrz vinna7Janti viftfta7Jancayatanarrz upasampajja viharati. Sabbaso vinfta1Jaftcayatanarrz samatikkamma natthi kinciti akincannayatanarrz upasampajja viharati. Sabbaso akincannayatanarrz upasampajja viharati. Sabbaso akincannayatanarrz samatikkamma nevasannanasannayatanarrz upasampajja viharati. Sabbaso nevasannanasannayatanarrz samatikkamma sannavedayita nirodharrz upasampajja viharati. !me kho bhikkhave, nava anupubba viharati.

While each of the limbs of the a/jfangayoga builds upon the one before (tasya bhumi(iu viniyogafl, III,6), this is not the case of the eightfold path of Buddhism; these items are to be practiced all together. However, the last three members of the eightfold path are meditation words, those of mental effort ( vyayama from the root yam-), mindfulness (smrti) and concentration (samadhi), the group of three, though, collectively being called samadhi. These three are reminscent of the last three members of Yoga, collectively called sar(lyama (III,4 et passim), again meaning "control". It is of course nothing new that the two systems of eight members seem to be competing systems of rhetoric trying to describe how to achieve human development by meditation.

Another meditation word, bhavana, which denotes "to make happen", or "to develop", and translated by Herbert Gilnther as "making a living experience of', has rather an epistemological or even pedagogical value: it is placed into the triad of srutamayf prajna, "insight derived from hearing, cintamayf prajna, "insight derived from pondering on", and lastly, bhavanamayf prajna, "insight developed into real understanding". This denotes a process of increased interiorization of learned knowledge rather than a process of meditation, though of course one might say that such interiorization of knowledge might be called a kind of meditation. With time, however, bhavana developed into a word for meditation, as did many other words for "pondering on" and "reflecting on", as with the term nidhyapti, which is used in a Mahayana context and may also mean "understanding". The movement from srutamayf through cintamayf to bhavanamayf, represents a movement from what we might in modern language style "only intellectual knowledge" as heard or learned, to something we take seriously and reflect and ponder upon, to a knowledge cultivated within ourselves to be integrated and part of our inner being.

With the Mahayana, meditation words became somewhat less important as part of this mostly, it would seem, literary movement placed great emphasis on intellectual discussions on the one hand, and on piety, faith, generous acts and ethics on the other. The meditation practices of monks and recluses were often derided, and the addiction to such a peaceful life, .§amabhirata, was nothing for the bodhisattva; he was in a state of meditation whatever he did, and he could enter any samadhi at will, preferably with a fanciful and long Sanskrit name. Additionally, the dhycmasvada, "tasting of meditation", was worse than Hell, thus addiction to inner meditational disciplines was depreciated to some extent.

This did not mean that meditation in all its forms would not further develop its terminology, and with Tantric Buddhism the word sadhana meant taking into the meditational practices of interiorizing a magical ritual for soteriological purposes, while the terms of utpattikrama and ni$pannakrama, developed as the "form phase" and "emptiness phase" of Tantric visualization.

We can see that the wortschatz of Yoga and Buddhist meditational practices are to some extent the same, but the placement of the words within the two systems is different, and so thus are their meanings. On occasion the meditation terminologies from the yoga-systems and the various sects of Buddhism have been promoted as particular methods in modem religious endeavours, but it is often difficult to see what distinguishes these methods from each other. One may often suspect that the technical terms of meditation are no more than rhetorical means used to promote this or that religious sect or psychological/therapeutic business idea. In some contexts, some of the "meditation words" may seem to an extent synonymous, however, in looking at the complexity of Indian words for "meditation", one may well reflect upon the richness of language such activities generated in classical India. One could extend this reflection further in considering how a huge, yet maybe not too well-defined terminology, is being generated today in a global context, either by Sanskrit or Pali loanwords, by Japanese or Chinese, or by translations and loan translations into Western languages. In the end, most of the words are historically connected with the Indian contexts.

Summary of terms

y: Yoga b: Buddhism m: Mahayana Buddhism

The Sanskrit form is given first, and the Pali second, if different.

bhavana - cultivation of knowledge, cf. sruta, learned, heard, and cinta, reflection, pondering on, with which bhavana creates a

trinity of increased understanding and awareness.

cinta - b, m: pondering on, reflecting on, cf. sruta and bhavana. dharm:za - being mentally focused on an object, the root is dhr-, to uphold, support, keep, in the case, in mind, y: the first and least developed stage of meditation

dharm:zf - cf. dharm:za, the two words are from the same root. Originally a prop, support; then, m: something to help remember and keep in mind, mnemotechnical aid, focus or prop of meditation, object of meditation, mantra, magical formula.

dhyana, jhana - b: the first four stages of meditation, cf. samadhi, but also a general word for meditation; m: the most general word for meditation, as in the list of "perfections",

dhyanaparamita; y: being continually focussed on and object of meditation, the second stage of meditation. Root: dhyai- cf. nidhyapti.

nidhyapti - also from the root dhyai- cf. dhyana, mostly m. The more cognitive part of meditation, as such often best translated as "consideration, or reflection on", cf. vipasyana, cf. also vitarka.

ni$pannakrama - m: "perfection phase", see sadhana and cf. utpattikrama.

sadhana - "making it happen" literally, m: a meditational procedure in the form of a written text employed in the Tantras to instruct both rituals and their interiorization as meditation. It usually has two main phases, utpattikrama and ni$pannakrama. The first one, the "generation phase" or "form phase", builds up the devotion to the chosen deity with mantras an inner or outer rituals, while the second, the "emptiness-" or "perfection phase" is where the meditator is supposed to merge with the deity in shining light and emptiness.

samadhi - y: advanced and absolute concentration, where there is no duality between meditator and meditated on, of subject and object; b: states of concentration attained in meditation, and

thus the states of consciousness of gods, living in heavens corresponding to such states of consciousness; m: the bodhisatva can attain such states at will in any relevant situation.

samapatti - generally "success", "attainment", in our context "success in meditation" or "attainment of meditational states"; in y: similar to the concept of samadhi; b: one of the four final and highest states of concentration.

Samatha, samatha - peace, b: inner peace, peaceful meditation.

smrti, sati - general word for remembrance, most important is to remember one's former lives, and thus profit in the present from all one has experienced and has had knowledge of in one's eter

nal cycle of rebirth in the past. The concept is more important in b than y, and here remembrance is also connected to the present, thus attaining the meaning of attention, recollection, awareness and mindfulness. In b, where it received a particular emphasis,

the "practice of mindfulness" smrtyupasthana, satipatthana, 1s seen as the only way to liberation.

sruta - learned heard, cf. cinta and bhiivana.

utpattikrama - "generation phase" or "form phase", see sadhana and cf. ni$pannakrama.

vicara - see vitarka

vipasyana, vipassana - seeing all around, expanded vision, b: "insight meditation". Cf. nidhyapti.

vitarka, vitakka - y, b: mainly logical investigation, but as such also a quality attained by meditation and concentration, coupled with vicara , "introspection" or "reflection".

vyayama - mental control and effort, keeping bad thoughts away and cultivating the good, preparation for meditation in b, item no. 6 in the eightfold path, the a${ango margafl.