''Chanting'' Practice for the Disabled

Foreword

In the Surangama Sutra (Yg), there are many special practices recommended by great Bodhisattvas who had attained Enlightenment through those practices which use only the functioning of a particular human faculty such as hearing, seeing, etc. Nevertheless, in the traditional teachings of the Pureland School of Buddhism there is hardly any mention of what a disabled person could practice in case he is unable to chant the holy name of Amitabha. Today there is a greater awareness for the well-being of disabled persons. Thus I felt an urgent need for introducing practices for disabled persons based on the basic principles underlying the practice of chanting Amitabha. In August 1991 I wrote an article in Chinese, titled "ݻ٩", to introduce "chanting" practices for people with various kinds of disability. It is included in my book "@Qu" which was published in 1991, 1992 and 1994 for free distribution. The present work is essentially based on that article.

A fundamental teaching of Buddhism is the impermanence of all things. Disability is also an impermanent condition which may befall on any one at any moment. The aging process brings with it various degrees of disability, and death will bring us total disability of physical functionality. Therefore, the practices introduced in this work are pertinent not only to those who are disabled but also to all of us.

May these practices bring peace and even Enlightenment to those who adopt them as daily practices. May the great Bodhisattvas who realized Enlightenment through practices involving special faculties, especially the all compassionate Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara who taught us to practice nonattachment through hearing, bless these practitioners.

"Chanting" Practice for Disabled Persons

Without regular exercise the physical functions of our bodies may deteriorate; likewise, the mental capabilities of our minds also need proper training and use to remain clear and alert. Training of the mind may be divided into two aspects: concentration practice and broadening of view. The former may help one to become free from distractions, indolence and absent-mindedness, while the latter may lead to the broadening, deepening and harmonizing of Wisdom and Compassion. It is essential that these two types of training be unified in balance, although usually the practical sequence of practice consists of doing the concentration practice first.

The practice of chanting Amitabha trains in both concentration and broadening of view. To maintain the pure thought of Amitabha requires concentratione the consequential detachment from personal worldly considerations brings about a natural broadening of mind. Through years of devoted chanting of the holy name Amitabha a natural balance of concentration and broadening evolves. As the mind becomes purer and purer, one's innate wisdom and compassion develop naturally in a balanced way.

Long-term and devoted practice of chanting Amitabha will bring about a constant feeling of peace of mind and an open attitude toward life and the world to such an extent that one's tranquility transcends the ups and downs of life and physical and mental well-being and suffering. Through the ages many Buddhist sages and teachers advocate to the general public the practice of chanting Amitabha with the hope that all may become free from suffering and abide in tranquility through adopting this practice. Nevertheless, in most cases there is no mention of how or what to practice in case a person is disabled. In order to fulfill the compassionate vows of all Buddhas which leave no sentient beings out, I am abstracting the underlying principle from the chanting practice in order to formulate various practices that will be suitable for persons with different kinds of disabilities.

Basically the practice of chanting a holy name or a mantra is to maintain the clarity and tranquility of mind through repetition of an expression, and thereby eventually achieve purity of thoughts. Therefore, a "chanting" practice for a disabled person should make use of a functioning faculty to do simple repetitive acts in order to maintain the clarity of mind and eventually attain one's original purity which is beyond the pollution of worldly considerations.

Keeping in mind the principle above, I will introduce various "chanting" practices with respect to particular human faculties. The classification below is a natural one because it is divided by the use of eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body and mind.

1. "Chanting" by eyes:

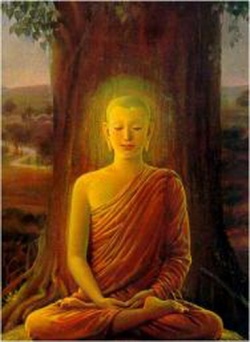

Choose an image of a Buddha or Bodhisattva for daily viewing. Sit quietly at a set time for a definite period and simply look at the image attentively. If the image chosen is small in size, one may carry it along for frequent viewing. Gradually it will become so familiar that as soon as one thinks of it, it will become vividly present just as though it is right in front of the person. One may also choose instead of a holy image a written holy name, mantra or tantric seed syllable for this practice. The key point of this practice is that the object of viewing should remain the same to facilitate the maturity of realization.

2. "Chanting" by ears:

Choose a chanting tape to listen to daily at a set time for a definite period, preferably a melodious one such as the Five Variations of Chanting "Amitabha" (|). It would be ideal to carry it with you and play it all the time; at least one would make use of commute hours by playing it in the car. Sooner or later the chanting will automatically play continuously in the practitioner's mind.

3. "Chanting" by nose:

There are two kinds of practice during which one would

- Be mindful of the breath and follow its flow in and out through the nostrils.

- Be mindful of the sense of smelling without exercising value judgments.

Both of these practices may be conducted on a daily basis or whenever one wishes. They should not be practiced simultaneously.

4. "Chanting" by tongue:

There are three kinds of practice during which one would

- Audibly or silently chant Amitabha with slight movement of the tongue.

- Rhythmically touch the upper palate with the tip of the tongue.

- Be mindful of the taste in the mouth without exercising value judgments.

All three practices may be conducted on a daily basis or whenever one wishes. They should not be practiced simultaneously.

5. "Chanting" by body:

There are four kinds of practice during which one would

- Prostrate to an image or the holy name of a Buddha with concentration and reverence at every step of the process.

- Hold a string of beads in one hand and continuously use the thumb to move the beads one at a time. Be mindful of the movement at all times.

- Use the tip of fingers to feel the pulse on the other wrist; be mindful of the pulsation.

- Use a hand, foot, finger or toe to tap a rhythmic tempo; be mindful of each tapping.

All these practices may be conducted on a daily basis or whenever one wishes.

6. "Chanting" by mind:

Continuously maintain a holy name, a mantra or a melodious chanting in one's heart as often as possible. This is the key point of a chanting practice. Generally speaking, any thought related to the merits or teachings of Buddha is a "chanting" on Buddha.

Both the daily yoga of tantric Buddhism and the Pure Conduct Chapter of the Avatamsaka Sutra are teachings on relating daily activities to the "chanting" on Buddha in the general sense. They teach us how to purify our minds in a lively manner free from artificial rituals.

After reading this article a person with normal faculties still intact can choose one of the practices mentioned above to exercise his mind. In case one becomes disabled through aging or accident, one may make use of this knowledge to practice "chanting" in one of the above ways or in a way designed by oneself in accordance with the same basic principle.

To people who are already disabled in some way without knowing in advance these "chanting" practices we may try to convey the message to them and show them in whatever way we can how to do one of these practices.

As to seriously disabled persons such as those in temporary or permanent coma or during the death process, although there is no way for them to learn of any practice, nevertheless we can pray for them and chant or play chanting tapes by their side to help relieve their burden of Karma and increase their merits. Whenever we dedicate the merits of our daily practice or Dharma activities to all sentient beings we should remember to especially include all those who are in such difficult situations as to be unable to do practice themselves. Salutation to Amitabha Buddha!

Salutation to the compassionate and merciful Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara who saves all beings from all suffering and hardship!

Salutation to Green Tara, a transformation of Avalokitesvara, born from his compassionate tears!