A Short Biography of Kobo Daishi

Kobo Daishi was born in 774, in what is now Kagawa Prefecture on the island of Shikoku. His father was a local provincial governor. A legend has it that his mother became pregnant after she had a dream of a Indian sage entering her abdomen.

At fifteen he went to the capital with his uncle. At eighteen, he entered the national university. At the time, the university was designed for producing government officials and its curriculum was based on the traditional Chinese Confucian educational system.

While in the capital, he was taught by a Buddhist monk named Gonso. He also received instructions for an esoteric Buddhist practice devoted to the Bodhisattva Kokuzo.

In 793, when he was twenty years old, he decided to enter the priesthood. He initially changed his name to Kyokai but later changed it to Nyoku. Finally, when he received full ordination as a priest, he took the name Kukai, which he kept for the remainder of his life.

When he was twenty-four he wrote an essay called "Indications of the Three Teachings" (Sango shiiki), explaining his reasons for entering the priesthood. He told of his dissatisfaction with everyday life and his search for meaning. He described a life of wandering in the mountains, living on wild plants and sleeping where he could with only one thin robe to shelter him in winter. He also told of studying scriptures and practicing esoteric rituals such as the Morning Star Meditation of Kokuzo that he had learned in Kyoto.

His early Buddhist experience wasn't confined to the mountains. Much of his time he spent studying sutras at temples, but he wrote, "my mind was still not fulfilled. So it was that I beseeched with all my heart to the enlightened Buddhas in all directions and in the past, present and future, that the essence of the ultimate truth of non-duality be revealed to me."

As a result of his prayer, he went to Kumedera temple. There, in a small stupa, he discovered a copy of the scripture known as the Dainichi-kyo. Finally he had found a teaching that matched the experiential knowledge he had gained in his mountain meditations:

"To be enlightened is simply to understand fully the true nature of your own mind. Understanding fully the true nature of your own mind is equal to understanding everything."

He studied the sutra intensively, but found it difficult to understand. He couldn't find anyone in Japan who could explain certain parts of the sutra to his satisfaction, so he decided to travel to China, where the text had been translated from the original Sanskrit into the classical Chinese form common in Japan. In 804 he received official permission to study abroad.

He traveled to China in company with an official mission that included the Japanese ambassador. Within four months of his arrival at the Chinese capital, he was accepted as a student of the master of esoteric Buddhism, Hui-kuo. During the next eight months, Hui-kuo instructed Kukai in esoteric Buddhist theory and practice and gave him the religious name Henjo Kongo meaning "universally illuminating adamantine one." He then selected this young, thirty-two year old Japanese monk as his successor.

In the same month as he designated Kukai his successor, Hui-kuo also told him, "You have received all that I have to transmit. Return now to your homeland and promulgate this teaching in order to increase the happiness of the people and promote peace in the land. " Hui-kuo died soon after.

Kukai returned to Japan in 806. The following year he went to the capital in Kyoto. He received permission to instruct others in what he had learned from Hui-kuo and soon gave an inaugural lecture on the Dainichi-kyo at Kumedera temple in Nara, the place where years earlier he had the text.

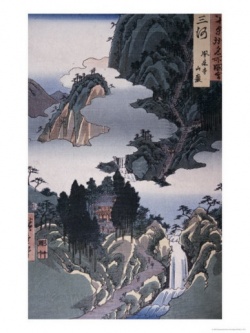

For the next ten years he taught what he had learned, living first at one, then at another temple near the capital. In 817, he was granted a mountainous tableland known as Koyasan to create a religious center for the training of priests in Shingon doctrine and practice.

He continually emphasized the importance of combining study and practice. This was how he came to his own understanding of truth, and he thought it important to create a center where others would have the same oportunity. Koyasan remains the headquarters of the main Shingon faction and the objective of tens of thousands of of visitors, Japanese and foreign, who come to see the temples and experience the ritual practices of Shingon.

Throughout the latter half of his life, Kukai continued to produce essays and poems setting forth Shingon doctrine. Among the most important of these are an essay, The Ten Levels of the Development of the Mind and a shorter work, summarizing the same same theme, The Precious Key to the Secret Treasury. These were written in response to an Imperial order, calling on each Buddhist sect to summarize its teachings. Both take as their starting point a passage in the Mahavairocana sutra that says enlightenment consists of knowing the mind as it really is. From that starting point, they set out the stages of the spiritual development of the mind from base, animal instinct to full realization of ultimate reality.

Kukai's activity was not limited merely to the promulgation of Shingon doctrine. He also founded the first private school in Japan open to the general public. Traditions about him include reports of his mastery of calligraphy, painting and sculpture. He is also revered as the inventor of the Japanese syllabary as well as being credited with discovering hot springs, instructing people in the use of coal, and constructing dams, bridges and roads.

In the first month of 835, he performed a week-long service for the peace and prosperity of Japan inside the Imperial palace. Then, in the second month, he announced his departure from Kyoto and headed for the last time to Koyasan.

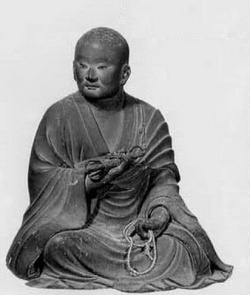

Upon arriving in Koyasan for his last time, he began a fast which included no grain or flesh and practiced seated meditation. On the 15th day of the 3rd month he called his disciples together in order to announce that on the 21st day he would pass away. Then, after ritually purifying his body and donning clean robes, he went to a room where he assumed the lotus position. Then he placed his hands in the mudra (ritual gesture) symbolizing Dainichi Nyorai, chanted the mantra of Dainichi, and entered the meditation of Maitreya (the Buddha of the future). He remained in this state for seven days until the 21st of the third month in 835, when he passed away, just as he had predicted. He was sixty-two years old. In 919, fifty eight years later, the Emperor Daigo bestowed upon him the posthumous honorific title Kobo Daishi, Great Master of the Propagated Teaching.