Acharya Nāgārjuna II

Acharya Nāgārjuna (c. 150 - 250 CE) was an Indian philosopher and the founder of the Madhyamaka school of Mahāyāna Buddhism.

His writings are the basis for the formation of the Madhyamaka school, which was transmitted to China under the name of the Three Treatise (Sanlun) School.

He is credited with developing the philosophy of the Prajnaparamita sutras, and was closely associated with the Buddhist university of Nalanda.

In the Jodo Shinshu branch of Buddhism, he is considered the First Patriarch.

Little is known about the actual life of the historical Nagarjuna. The two most extensive biographies of Nagarjuna, one in Chinese and the other in Tibetan, were written many centuries after his life and incorporate much lively but historically unreliable material which sometimes reaches mythic proportions.

Nagarjuna was born a Brahmin, which in his time connoted religious allegiance to the Vedas, probably into an upper-caste Brahmin family and probably in the southern Andhra region of India.

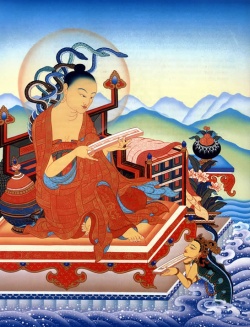

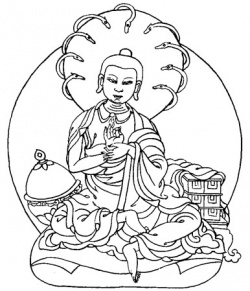

Iconography and hagiography

Nāgārjuna is often depicted in composite form comprising human and naga characteristics. Often the naga aspect forms a canopy crowning and shielding his human head.

The notion of the naga is found throughout Indian religious culture, and typically signifies an intelligent serpent or dragon, who is responsible for the rains, lakes and other bodies of water. In Buddhism, it is a synonym for a realized arhat, or wise person in general. The term also means "elephant".

History

Very few details on the life of Nāgārjuna are known, although many legends exist.

He was born in Southern India, near the town of Nagarjunakonda in present day Nagarjuna Sagar in the Nalgonda district of Andhra Pradesh. According to traditional biographers and historians such as Kumarajiva, he was born into a Brahmin family, but later converted to Buddhism.

This may be the reason he was one of the earliest significant Buddhist thinkers to write in classical Sanskrit rather than Pāli or Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit.

From studying his writings, it is clear that Nāgārjuna was conversant with many of the Nikaya school philosophies and with the emerging Mahāyāna tradition.

However, affilitation to a specific Nikaya school is difficult, considering much of this material is presently lost.

If the most commonly accepted attribution of texts (that of Christian Lindtner) holds, then he was clearly a Māhayānist, but his philosophy holds assiduously to the non-Mahāyāna canon, and while he does make explicit references to Mahāyāna texts, he is always careful to stay within the parameters set out by the canon.

Nagarjuna may have arrived at his positions from a desire to achieve a consistent exegesis of the Buddha's doctrine as recorded in the Canon.

In the eyes of Nagarjuna the Buddha was not merely a forerunner, but the very founder of the Madhyamaka system. David Kalupahana sees Nagarjuna as a successor to Moggaliputta-Tissa in being a champion of the middle-way and a reviver of the original philosophical ideals of the Buddha.

Writings

There exist a number of influential texts attributed to Nāgārjuna, although most were probably written by later authors.

The only work that all scholars agree is Nagarjuna's is the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā (Fundamental Verses on the Middle Way), which contains the essentials of his thought in twenty-seven short chapters.

According to Lindtner the works definitely written by Nagarjuna are:

Mūlamadhyamaka-kārikā (Fundamental Verses of the Middle Way)

Śūnyatāsaptati (Seventy Verses on Emptiness)

Vigrahavyāvartanī (The End of Disputes)

Vaidalyaprakaraṇa (Pulverizing the Categories)

Vyavahārasiddhi (Proof of Convention)

Yuktiṣāṣṭika (Sixty Verses on Reasoning)

Catuḥstava (Hymn to the Absolute Reality)

Ratnāvalī (Precious Garland)

Pratītyasamutpādahṝdayakārika (Constituents of Dependent Arising)

Sūtrasamuccaya

Bodhicittavivaraṇa (Exposition of the Enlightened Mind)

Suhṛllekha (To a Good Friend)

Bodhisaṃbhāra (Requisites of Enlightenment)

Sushruta Samhita (Redactor of Ayurvedic Medicine text)

There are other works attributed to Nāgārjuna, some of which may be genuine and some not. In particular, several important works of esoteric Buddhism (most notably the Pañcakrama or "Five Stages") are attributed to Nāgārjuna and his disciples.

Contemporary research suggests that these works are datable to a significantly later period in Buddhist history (late eighth or early ninth century), but the tradition of which they are a part maintains that they are the work of the Mādhyamika Nāgārjuna and his school.

Traditional historians (for example, the 17th century Tibetan Tāranātha), aware of the chronological difficulties involved, account for the anachronism via a variety of theories, such as the propagation of later writings via mystical revelation.

A useful summary of this tradition, its literature, and historiography may be found in Wedemeyer 2007. Lindtner considers that the Māhaprajñāparamitopadeśa, a huge commentary on the Large Prajñāparamita not to be a genuine work of Nāgārjuna.

This is only extant in a Chinese translation by Kumārajīva.

There is much discussion as to whether this is a work of Nāgārjuna, or someone else. Étienne Lamotte, who translated one third of the Upadeśa into French, felt that it was the work of a North Indian bhikkhu of the Sarvāstivāda school, who later became a convert to the Mahayana.

The Chinese scholar-monk Yin Shun felt that it was the work of a South Indian, and that Nāgārjuna was quite possibly the author.

Actually, these two views are not necessarily in opposition, and a South Indian Nāgārjuna could well have studied in the northern Sarvāstivāda.

Neither of the two felt that it was composed by Kumārajīva which others have rashly suggested.

Philosophy

Nāgārjuna's primary contribution to Buddhist philosophy is in the further development of the concept of śūnyatā, or "emptiness," which brings together other key Buddhist doctrines, particularly anatta (no-self) and pratītyasamutpāda (dependent origination).

For Nāgārjuna, it is not merely sentient beings that are empty of ātman;

all phenomena are without any svabhāva, literally "own-nature" or "self-nature",

and thus without any underlying essence; they are empty of being independent.

This is so because they are arisen dependently: not by their own power, but by depending on conditions leading to their coming into existence, as opposed to being.

Nāgārjuna was also instrumental in the development of the two-truths doctrine, which claims that there are two levels of truth in Buddhist teaching, one which is directly (ultimately) true, and one which is only conventionally or instrumentally true, commonly called upāya in later Mahāyāna writings.

Nāgārjuna drew on an early version of this doctrine found in the Kaccāyanagotta Sutta, which distinguishes nītārtha (clear) and neyārtha (obscure) terms -

By and large, Kaccayana, this world is supported by a polarity, that of existence and non-existence. But when one reads the origination of the world as it actually is with right discernment, 'non-existence' with reference to the world does not occur to one. When one reads the cessation of the world as it actually is with right discernment, 'existence' with reference to the world does not occur to one.

"By and large, Kaccayana, this world is in bondage to attachments, clingings (sustenances), and biases. But one such as this does not get involved with or cling to these attachments, clingings, fixations of awareness, biases, or obsessions; nor is he resolved on 'my self.' He has no uncertainty or doubt that just stress, when arising, is arising; stress, when passing away, is passing away. In this, his knowledge is independent of others. It's to this extent, Kaccayana, that there is right view.

"'Everything exists': That is one extreme. 'Everything doesn't exist': That is a second extreme. Avoiding these two extremes, the Tathagata teaches the Dhamma via the middle..."

Nāgārjuna differentiates between saṃvṛti (conventional) and paramārtha (ultimately true) teachings, but he never declares any to fall in this latter category; for him, even śūnyatā is śūnya--even emptiness is empty. For him, ultimately,

nivṛttam abhidhātavyaṃ nivṛtte cittagocare

anutpannāniruddhā hi nirvāṇam iva dharmatā

The designable is ceased when the range of thought is ceased,

For phenomenality is like nirvana, unarisen and unstopped.

This was famously rendered in his tetralemma with the logical propositions: X, not X, X and not X, neither X nor not X. "The designable is ceased when the range of thought is ceased" is the premise upon which the Mindstream Doctrine is founded.