The Breath of Life: The Practice of Breath Meditation

Why we meditate

Meditation is all about freedom. Only a fraction of the world’s population is formally imprisoned, but the entire human race is imprisoned in the body and the earth itself. None are free from the inevitability of sickness, age, and death, however free of them they may be at the moment. The human condition is subject to innumerable limitations. Who really controls his life fully, attains all his goals, and knows no setbacks of any kind? No one.

Our real self, the spirit, is ever perfect and free. But we have forgotten that. So we identify with our present experience of bondage and consequently suffer in countless ways. Our situation is like someone who is asleep and dreaming that he is being tortured and beaten. In reality he is not being touched at all; yet he is experiencing very real pain and fear. He need not placate, overpower, or escape his torturers. He needs only to wake up. Meditation is the way of self-awakening, the way to freedom from suffering and limitation.

Meditation is the way of remembrance and restoration. A person suffering from amnesia has not ceased to be who he really is, but he needs to regain his memory. The memory block from which we suffer is the condition of the various levels on which we presently function, especially the mind. It is also a matter of the dislocation of our consciousness from its natural center.

Meditation is the process of re-centering our awareness in the principle of pure consciousness which is our essential being. We have lost awareness of our true Self through awareness of external objects, and become habituated–even addicted–to objective consciousness. Rather than disperse our consciousness through objects that draw us outward, away from the center of our being, we can take an object that will have the opposite effect, present it to the mind, and reverse our consciousness. That object is the breath, which is the meeting place of body, mind, and spirit.

The breath and the body are interconnected, as is seen from the fact that the breath is calm when the body is calm, and agitated or labored when the body is agitated or labored. The heavy exhalation made when feeling exhausted and the enthusiastic inhalation made when feeling energized or exhilarated establish the same fact.

The breath and the emotions are interconnected, as is seen from the fact that the breath is calm when the emotions are calm, and agitated and labored when the emotions are agitated or out of control. Our drawing of a quick breath when we are surprised, shocked, or fearful, and the forceful exhalation done when angry or annoyed demonstrate this.

The breath and the mind are interconnected, as is seen from the fact that the breath is calm when the mind is calm, and agitated, irregular, and labored when the mind is agitated or disturbed in any way. Our holding of the breath when attempting intense concentration also shows this.

Breath, which exists on all planes of manifestation, is the connecting link between matter and energy on the one hand and consciousness and mind on the other. By sitting with closed eyes and letting the mind become easefully absorbed in observing and experiencing the movements of the breath we enter into the consciousness from which it arises–the eternal Witness Consciousness.

We start with awareness of the ordinary physical breath, but that awareness, when cultivated correctly, leads us into higher awareness which enables us to perceive the subtle movement behind the breath. Ultimately, we come into contact with the Breather of the breath, our own Spirit-Self.

In many spiritual traditions the same word is used for both breath and spirit, underscoring the esoteric principle that in essence they are the same, though we naturally think of spirit as being the cause of breath(ing). The word used for both breath and spirit is: In Judaism: Ruach. In Eastern Christianity (and ancient Greek religion): Pneuma. In Western Christianity (and ancient Roman religion): Spiritus (which comes from spiro: “I breathe”). In Hinduism and Buddhism: Atma (from the root word at which means “to breathe”), and Prana. Meditation on the breath is meditation on spirit, on consciousness itself.

Back to the Source

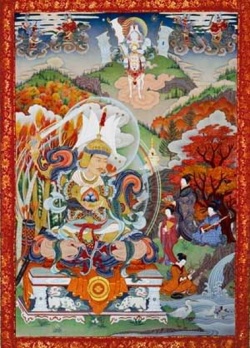

We are without origin, for we are eternal, without beginning or end. Yet we are not without a Source, for we are rooted in the Being that is called Brahman, Dharmakaya (Original Nature), Tao, or God. The names matter little, but the Reality is everything–including us.

Originally we were unmanifest, as transcendental as our Source. But just as the Source expanded into relative manifestation, so did we. In our undifferentiated being, the state of perfect unity, there manifested a single point. This did not upset or disrupt the original unity but it stressed it. Then, so imperceptibly and subtly as to hardly have even occurred, that stress point began to move internally, producing a magnetic duality so subtle it was really more an idea than an actual state. This was the Original Breath. Then the halves or poles of that duality began alternating in dominance, and a cycling or circling began. This cycling expanded outward, manifesting as embodiment in increasingly more objective body-vehicles, until at last the full state of relativity was reached. Like the bit of grit in an oyster, the Original Breath had become or produced everything we call “us.” The same thing had already happened to our Source on a cosmic level. So through the permutations of the Cosmic Breath we found a virtually infinite environment for our manifestation. This is the process known as samsara.

This had a practical purpose. The breath is the evolutionary force which causes us to enter into relative existence and manifest therein until–also through the breath–we evolve to the point where we are ready to return to our original status. To turn back from the multiplicity of relativity and return to our original unity we must center our awareness in that primal impulse to duality which is manifesting most objectively as the process of our physical inhaling and exhaling. These seemingly two movements are in reality one, inseparable from one another, and together are capable of leading us back to their–and our–source. Through our full attention focused on the entire process of inhalation and exhalation, we become immersed in the subtler levels of that alternating cycle, moving into deeper and deeper levels until we at last come to the originating point. Then transcending that dual movement, we regain our lost unity. By continual practice of that transcendence we will become established in that unity and freed forever from all forms of bondage, having attained Nirvana: permanent unbinding. This is why the contemporary Thai Buddhist Master Ajaan Fuang Jotiko said: “The breath can take you all the way to Nirvana,” and Sri Ma Anandamayi, perhaps the most renowned spiritual figure of India in the latter half of the twentieth century, said: “Nothing can be achieved without cultivation of the breath.” This is done through the process simply known as Breath Meditation, for the breath is both entry and exit.

The practice of Breath Meditation

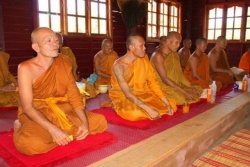

1) Sit upright, comfortable and relaxed, with your hands on your knees or thighs, palms up or palms down or resting, one on the other, in your lap.

2) Turn your eyes slightly downward and close them gently. This removes visual distractions and reduces your brain-wave activity by about seventy-five percent, thus helping to calm the mind.

3) Your mouth should be closed so all breathing is done through the nose. This, too, aids in quieting the mind. Though your mouth is closed, the jaw muscles should be relaxed so the upper and lower teeth are not clenched or touching one another, but parted.

4) Inhale and exhale slowly and deeply three or four times, feeling the inhaling and exhaling breath moving in and out through your nostrils.

5) Now breathe naturally and easefully, keeping your awareness on the tip of your nose, feeling the breath as it flows in and out of your nostrils. (Some people become more aware of the half-inch or so at the end of the nose, others the very end of the nose, and others remain more aware of the nostrils. Whichever happens naturally is the best for you. So whenever this book says “nosetip” it applies equally to these three areas.) Do not follow the breath in and out of your body, but just be aware of the breath movement sensation at the tip of your nose.

6) Keeping your awareness on the tip of your nose, breathe naturally and calmly, easefully observing the sensation of the breath moving there throughout all your inhalations and exhalations. This enables you to enter effortlessly into the Witness Consciousness that is your true nature.

7) Do this for the rest of the meditation, letting your awareness rest gently on the breath at the nosetip and feeling the sensations of the breath moving there. After a while it may feel as though the breath is flowing in and out the tip of your nose more than the actual nostrils, or you may not feel the nose at all, but just the breath moving at the point in front of your face where the nose is located. That is perfectly all right, but the focus of your attention should be only at that point–not somewhere else either outside or inside the body.

8) Let the breath be as it will. If the breath is naturally long, let it be so. If it is short, let it be so. If the inhalations and exhalations are of unequal length, that is just fine. Let the breath be natural and unforced, and just observe and experience it.

In time your breath will become more subtle and refined, and slow down. Sometimes your breath can become so light that it almost seems as though you are not breathing at all. At such times you may perceive that your inhaling and exhaling are more like a magnetic pull or flow in and out instead of actual breath movements. This occurs as the subtle life force (prana) that produces the breath switches back and forth in polarity from positive to negative. It is also normal for your breath awareness to move back and forth from more objective to more subtle and back to more objective.

Sometimes the subtle breath is silent, but at other times you will inwardly “hear” the breath making sounds as it moves in and out. These will not be actual physical sounds, but very subtle mental sounds. They may be like the sounds made by forceful or heavy inhalation and exhalation–except softer–or they may be quite different. Whatever they may be, just be calmly aware of them while staying centered on the nosetip and breath.

The breath is a kind of barometer of the subtle energies of body and mind. Sometimes it is very smooth, light and easeful, and at other times it feels heavy, even constricted, or clogged, sticky, ragged, uneven, and generally uncomfortable and somehow feels “not right.” When this occurs, do not try to interfere with it or “make it better.” Rather, just relax and be calmly aware and let it be as it is. If you do this, the problem in the subtle energy levels which the breath is reflecting will correct itself and the breath will become easy and pleasant.

9) In Breath Meditation we only focus our awareness on the breath at the nosetip/nostrils, and not on any other point of the body such as the “third eye.” However, as you meditate you may become aware of one or more areas of your body at different times. This is all right when it comes and goes spontaneously, but keep centered on your nosetip and your breath.

10) Thoughts, impressions, memories, inner sensations, and suchlike may also arise during meditation. Be calmly aware of all these things in a detached and objective manner. Let them come and go as they will, but keep your attention centered on the tip of the nose and your breath moving there. Be indifferent to any inner or outer phenomena. Breath Meditation produces peace, awareness and quiet joy in your mind as well as soothing radiations of energy in the physical and subtle bodies. Be calmly aware of all these things in a detached and objective manner–they are part of the transforming effect of meditation, and are perfectly all right–but keep your attention centered in your breath. Even though something feels very right or good when it occurs, it should not be forced or hung on to. The sum and substance of it all is this: It is not the experience we are after, but the effect.

11) If you find yourself getting restless, distracted, fuzzy, anxious or tense in any degree, just inhale and exhale slowly and deeply a few times, feeling the inhaling and exhaling breath moving in and out through your nostrils, at the same time feeling that you are releasing and breathing out all tensions. Then resume meditating as before. Relaxation is the key to successful meditation practice.

12) Keep in mind that Breath Meditation basically consists of being aware in a relaxed and easeful manner of your breath as it moves in and out at the tip of your nose. That is all!

At the end of your meditation time, keep on being calmly aware of your breath moving in and out of your nosetip as you go about your various activities. In this way you can maintain the calm and clear state of meditation.

Meditation checkpoints

Occasionally in your meditation it is good to check three things: 1) Am I aware of the tip of my nose? 2) Am I continually experiencing the movement or energy-flow of the breath at or in the tip of my nose? 3) Am I aware of the breath movement throughout the entire duration of each inhalation and exhalation? These are the essential points of Breath Meditation.

Simple and easy

Can it be that simple and easy? Yes, it can, and is. Suppose some people who have always lived in tents entered a house and came upon a locked door. Knowing nothing of doors, locks, and keys, how would they open it? They might throw themselves against it, beat on it with their fists or heavy objects such as sledgehammers or even some kind of battering ram. If someone approached them with a tiny key they could easily snap in two and told them it would open the door, they would laugh at him. But he would simply insert the key, turn it, and enter. It would be that simple and that easy. Breath Meditation is also that simple and easy because it goes directly to the root of our bondage which is a single (and therefore simple) thing: loss of awareness.

Not only that, Breath Meditation is so natural and spontaneous that it teaches us about itself–the actual practice, its meaning, purpose and effect. The more we practice, the more our spiritual intuition comes to the fore and becomes our instructor. As Vyasa, the author of the Bhagavad Gita, said in his commentary on the Yoga Sutras: “Yoga is to be known by yoga. Yoga goes forward from yoga alone. He who is not careless [neglectful] in his yoga for a long time, rejoices in the yoga.”

Now let us look at the various components of our Breath Meditation practice so we can understand it fully.

The posture for meditation

For Breath Meditation we sit in a comfortable, upright position. This is for two reasons: so we will not fall asleep, and to facilitate the upward movement of the subtle life force called prana, of which the breath is a manifestation.

It is important that our meditation posture be comfortable and easy to maintain. Though sitting upright, be sure you are always relaxed. Yoga Sutra 2:46 says: “Posture (asana) should be steady and comfortable.” The Yoga Vashishtha (6:1:128) simply says: “He should sit on a soft seat in a comfortable posture conducive to equilibrium.” India’s great yogi-philosopher Shankara comments: “Let him practice a posture in which, when established, his mind and limbs will become steady, and which does not cause pain.” Here relaxation is the key, for Yoga Sutra 2:47 says: “Posture is mastered by relaxation.”

If you can sit in a cross-legged position without your legs going to sleep and making you have to shift them frequently, that is very good. There are several cross-legged postures recommended for meditation. You will find them described in books on Hatha Yoga. I especially recommend Yoga Asanas by Swami Sivananda of the Divine Life Society, as it is written from the perspective of spiritual development and also gives many hints to help those who are taking up meditation later in life and whose bodies need special training or compensation.

Some meditators prefer to sit on the floor using a pillow and/or a mat. This, too, is fine if your legs do not go to sleep and distract you. But meditation done in a chair is equally as good. Better to sit at ease in a chair and be aware only of the breath than to sit cross-legged and be mostly aware of your poor, protesting legs.

If you use a chair, it should be comfortable, of moderate height, one that allows you to sit upright with ease while relaxed, with your feet flat on the floor. There is no objection to your back touching the back of the chair, either, as long as your spine will be straight. If you can easily sit upright without any support and prefer to do so, that is all right, too, but be sure you are always relaxed.

If you have any back difficulties, make compensation for them, and do not mind if you cannot sit fully upright. We work with what we have, the whole idea being to sit comfortably and at ease.

Hold your head so the chin is parallel to the ground or, as Shankara directs, “the chin should be held a fist’s breadth away from the chest.” Make a fist, hold it against your neck, and let your chin rest on your curled-together thumb and forefinger. You need not be painfully exact, about this. The idea is to hold your head at such an angle that it will not fall forward when you relax. Otherwise you may be afflicted with what meditators call “the bobs”–the upper body continually falling forward during meditation.

It does not matter how you place or position your hands, just as long as they are comfortable and you can forget about them. There is no need to bother with mudras as they are irrelevant to Breath Meditation practice.

Meditation is not a military exercise, so we need not be hard on ourselves about not moving in meditation. Move and even stretch occasionally if you find it benefits.

Reclining meditation

If we lie down for meditation we will likely go to sleep. Yet for those with back problems or some other situation interfering with their sitting upright, or who have trouble sitting upright for a long time, it is possible to meditate in a reclining position at a forty-five-degree angle. There may be a tendency to sleep, but we do what we can as we can.

Using a foam wedge with a forty-five-degree angle–or enough pillows to lie at that angle, or in a bed that raises up to that angle–lie on your back with your arms at your side, or across your stomach if that is more comfortable. Then engage in the meditation process just as you would if sitting upright.

When you are ill or for some reason unable to sit upright you can meditate in this way.

Alternating positions in meditation

Those not yet accustomed to sitting still for a long time, or those who want to meditate an especially long time, can alternate their meditation positions. After sitting as long as is comfortable, they can do some reclining meditation and then sit for some more time–according to their inclination.

Relax

During meditation, distracting thoughts and impressions arise mostly from physical or mental tension. To relax and be quietly observant of the breath at the nosetip is the prevention and cure. It is in the nature of things for your mind to move up and down–or in and out–during the practice of meditation, sometimes calm and sometimes restless. Do not mind this at all. Stay relaxed, at peace, and aware of the breath at the nosetip. You will find that this is the remedy for all problems in meditation.

As already said, when restlessness or distractions occur, take one or more deep breaths through your nose, breathe out, relax, and keep on meditating.

Closed eyes and mouth

By closing your eyes you remove visual distractions and eliminate over seventy-five percent of the usual brain wave activity, both calming and freeing the mind for absorption in meditation. Breathing through the mouth agitates the mind, so keeping your mouth closed and breathing only through the nose has a calming effect on both body and mind.

Breath awareness

We do not need to control the breath, only to experience, for if we fix our awareness on it and let it move as it will, it will carry us onward to perfect spirit-consciousness. Simple breath awareness actually frees the breath–and our consciousness–from the blockages and static condition that have been produced by our being out of harmony with the cosmic order whose fundamental purpose is evolution through development of consciousness.

The breath is the primal manifestation of duality, and at its roots is the unity of pure awareness. The breath combines in itself both energy and consciousness. When we examine its nature, we see that the breath is not a “thing,” but a process which has the power to draw us into the core point from which it arises–the Self whose nature is consciousness–changing all the levels of our being. Awareness of breath produces awareness of awareness, consciousness of spirit.

There are two breaths, the outer breath and the subtle inner breath which produces it. By centering our awareness on the outer breath we enable ourselves to become aware of the inner breath. By attuning ourselves to them we attune ourselves to the spirit from which they take their origin. Observing the breath releases the spirit-soul consciousness which includes the spiritual will. In this way the spirit takes control of our life and directs it.

We keep our awareness on both the inhaling and exhaling breaths because they are manifestation/reflections of the two poles that are found in every existing object. The subtle currents that emanate from these two poles have become all the forms of energy within the physical and subtle bodies. These currents move outward and manifest as inhalation and exhalation. Within the body the two breaths are the forces of positive and negative, yin and yang, which affect the two sides of the meditator’s being. Ultimately they are one, and each breath moves us toward unity.

In all relative beings the prana-breath has become corrupted and confused, binding the consciousness rather than freeing it. It has gotten out of phase, out of tune, or off key–out of alignment with its original, natural pattern of movement. By deeply observing his breath, the meditator realigns and repolarizes it, effortlessly restoring it to its original form and function. In this way he sets himself squarely in the upward-moving stream of evolution and accelerates his movement within it.

Effective attention

Breath Meditation was called Anapanasati by Buddha. Anapana means inhalation and exhalation. Sati means deliberate attention, not just simple involuntary awareness. At first in our practice we are simply aware of the breath, but after some time we will find that the breath makes us aware of awareness itself. Then anapanasati means the awareness produced by–or inherent in–the breath.

It is possible to pray, sing, or recite mantras without really paying any attention to them–even thinking of other things–but you cannot practice breath awareness at the tip of the nose without being very aware of it. Breath awareness ensures that the yogi’s mind remains one-pointed. As the Gita says: “The light of a lamp does not flicker in a windless place: that is the simile which describes a yogi of one-pointed mind” (Bhagavad Gita 6:19).

Although we tend to think of attention as merely a state of the mind, the opposite of inattention, it is really a great psychic force. Quantum physics has discovered that when a human being sets his attention on anything, that object is immediately affected to some degree–so much so that a scientist can unintentionally influence the result of an experiment, however controlled the external conditions may be. Thoughts are indeed things, but attention is the fundamental power of thought.

As we calmly fix our awareness on the breath, it becomes increasingly refined, gentle and easeful, often as light as the breeze of a butterfly’s wings. The subtler the breath sensations the closer the awareness is coming to the Self, and therefore the more easeful and joyful the experience. To experience the breath fully is to experience the Self. When the breath disappears, Self-awareness remains.

Since it is natural for the breath to become increasingly refined as you observe it, you need not attempt to deliberately make this happen. Your attention will automatically refine it. As we become more and more aware of the subtle forms or movements of the inner breaths, it automatically happens that the breath movements on all levels become slower. This is the highest form of pranayama.

The more attention we give to the breath, the subtler it becomes until it reveals itself as an act of the mind, consisting of mind-stuff (chitta) itself. The breath, like an onion, has many layers. In the practice of Breath Meditation we experience these layers, beginning with the most objective, physical layer and progressing to increasingly subtle layers, until, as with an onion at its core, there are no more layers, but only pure being (consciousness). The breath becomes increasingly refined as we observe it, and as a result our awareness also becomes refined.

When the breath seems not right, or uncomfortable or unsatisfactory in some way, it is the simple power of attention (sati) that will make everything right in time. This is important to realize, for at such times of discontent with the breath we are actually confronting blockages or entanglements in the various levels of our being. If we try to correct them or banish them we may make them worse. But calm and disinterested observation/awareness of the breath, ignoring its momentary qualities, will straighten everything out by removing those blockages or problems. This especially takes place in the mind. So just keep watching–relaxed attention takes care of it all.

The same is true when we experience the inner, subtle sounds of the breath. The life-energies, called prana, which manifest as the breath are also manifesting as the physical and subtle bodies. That is why the upanishads declare that everything is prana-breath. As the prana of those bodies move or vibrate within them, much as many currents move within a river or ocean, they produce subtle sounds of varying frequencies. Therefore when you are deep in breath awareness you may hear many different forms of subtle sound as those pranic flows are being strengthened, enhanced, or corrected by your effective attention (sati).

Sri Ramana Maharshi said that internalized attention placed on the mind would cause it to resolve into the Self, the pure consciousness from which it arose. We experience this for ourselves in Breath Meditation, when the breath becomes revealed as not just an act of the mind, but the mind itself–which then resolves into the pure consciousness of our spiritual being, the Self.

Attention is the therapeutic spotlight of our consciousness, revealing, restoring, and perfecting. So it is attention–literally pure and simple–that makes Breath Meditation work.

The tip of the nose

In Hindu, Buddhist, and Taoist traditions meditators are told to fix their attention on the tip of the nose. This has the obvious practical value of giving us a steady point of reference so our minds do not drift around during meditation. But there is much more to it, as the faithful meditator will discover. The tip of the nose is the best point to focus attention and the best point for subtle perception.

Nosetip awareness ensures that you will not get lost in the many strands or currents of the subtle prana-breath, but will only be aware of the breath currents of inhalation and exhalation (prana/apana) that are the heart of the spirit-breath.

In relative existence we are constantly pulled between two poles, both experientially and philosophically: form and formlessness, duality and unity, embodied and disembodied, bound and freed, unconscious and conscious, matter and spirit, infinite and finite. Unfortunately we tend to think of choosing and becoming identified with one the other, when we need to transcend them. In Breath Meditation we fix our attention on the nosetip because it is neither within the body nor outside the body, and therefore the point of attention from which we can slip, untouched between and beyond the poles that bind us.

Buddha never omitted awareness of the nosetip in his meditation instructions, and neither do the classical Buddhist manuals on meditation and the contemporary Buddhist teachers cited in the Buddhist Tradition chapter of this book. Buddha taught that at the beginning of Breath Meditation we should put our attention parimukha, which means both “in front of the face” and “above the mouth”–in other words: the nosetip.

It should be understood that “nosetip” means much more than the cartilage and skin of the nose, but rather the point within the subtle levels of our existence that correspond to the physical nosetip. It is from here that the real breath is experienced.

Since this form of meditation is called Breath Meditation we should not forget that our relaxed awareness should always be on/in the breath. To do that we observe our breath at the nosetip, for that is the best place for us to become fully aware of the breath. The attention to the breath as it moves through/at the nosetip is like the drawing of a string between the joined tips of the forefinger and thumb. We only feel and are aware of the string and its movement at the point where the fingers are joined. In the same way, we are aware of the breath movements in/at the nose.

Buddhist writers on Breath Meditation use the simile of the gatekeeper of a city: the traffic moves in and out in a continual stream, but his attention is at the gate alone. He sees everyone going and coming, but he follows after no one. (I think of it as being like someone putting their finger lightly on a moving belt: he will feel the motion, yet his awareness will remain at the fingertip.) In the same way, we keep our attention at the gate of the nosetip, watching the ingoing breath arriving there and the outgoing breath departing there.

It is natural for your awareness of the nosetip and the breath to sometimes get vague or out of focus, or your attention to get fuzzy or drifty. When this happens, just take some careful, long breaths through your nose, being very aware of the breath movement at the tip of the nose, and that will refocus your awareness. Do not hesitate to even reach up and touch your nosetip and make sure your awareness is centered there.

Just as the breath becomes refined, so does our awareness. Sometimes after a while in meditation we may lose the more physical awareness of our nosetip and become aware of it as a point in front of our face, the “point of attention” of which the nosetip is just the most objective manifestation. This is perfectly all right, as long as we keep aware of that point and remain aware of the breath-movement there, even though its subtle forms may be more like a magnetic pull or flow rather than a movement of breath (air), or even a kind of switching of the polarity of the breath.

Since you can be aware of the breath and not aware of the nosetip–but not aware of the nosetip and not be aware of the breath–it is awareness of the nosetip that is the key to the effective practice of anapanasati. Also, if we make ourselves aware of the breath alone, we will stay aware of the physical breath only. But if we hold to awareness of the nosetip we will become aware of the inner, increasingly subtle breath that is the real Breath of Life.

So when you have gained some proficiency in Breath Meditation you will find that a simple focussing of the attention on the nosetip will make everything else follow in good order. Just as closing the eyes eliminates a great deal of brain-wave activity, so also merging the attention into the tip of the nose disengages the machinery of the mind to a great extent and cuts down on random thoughts. At the same time, however, the higher faculties of intuition become engaged and render the meditator capable of profound intuitive insight (vipassana).

Why the tip of the nose?

Speech and most language originate in the subconscious. Therefore we often say things of which we have only subliminal knowledge. For example, although few people believe in (and even less can see) the phenomenon known as the aura–the field of subtle, colored energies that surround the body–it is common for just about everyone to use expressions regarding the aura. When someone is clever we say they are “bright” and when they are unintelligent we say they are “dull.” When cowardly we say they are “yellow.” We say that people are “green with envy” that jealous people have “green eyes.” If we are feeling down we say we are “blue,” and when we feel very well we say we are “in the pink.” When angry we say that we “see red.” And it is not uncommon to hear about “purple passion.” All these things attest to a subconscious knowledge of the aura.

It is the same with the nose. We talk about people having “a nose for news,” call inquisitive people “nosey,” and speak of those trying to find things out as “nosing around.” Those who are extremely intent on their work are said to have their “nose to the grindstone.” All of these terms link the nose with the capacity for attention and perception. There must be validity to these applications, for in both Hindu and Buddhist traditions meditators are told to fix their attention on the tip of the nose. This has the obvious practical value of giving us a steady point of reference so our minds do not drift around during meditation. But there is much more to it, as the faithful meditator will discover. The tip of the nose is the best point to focus attention and the best point for pure perception.

Why is this? Because the body is literally congealed karma. That is, the physical body is the objective manifestation of the karmic forces (energies) created in previous lives–forces that have impelled us into incarnation within its bonds. In one sense the body is a bundle of ignorance, a heap of delusions. It is our own private net in which we find ourselves helplessly caught. To enter within this house of illusion during meditation is to risk being caught up in the subtle energies of karma and becoming even more under their bondage, even more deceived by their false ways. Yes, some types of meditation can make us more ignorant and more enslaved! Which is why Buddha counseled Right Meditation as a factor for liberation.

There are various energy-points and energy-reservoirs throughout the body that are whorls of karmic force, energy mechanisms which maintain the entire system of karmic bondage. These centers are powerful repositories of karmic seeds, and their energization can produce the fruition of these seeds, resulting in even more karmic entanglements. Furthermore, these centers are the producers of various “states of consciousness” that are really nothing but psychic hallucinations, virulent germs and viruses that cause the multifarious diseases of samsara. To merely touch these whirlpools results in our being drawn into them, whirled around in their confusion, and drowned in their deadly illusion: the sleep of death that we erroneously call “life.”

For this reason the process of meditation must take place virtually outside the body–at the nosetip which is not really in the body, and where the (inner liberating) breath flows. We must at least “touch” the body through nosetip awareness, for if we were to set our attention at a point out in space beyond the body, that would dissipate our awareness and result in illusory “out-of body-experiences” or simple mental disorientation that would terminate in profound sleep.

When the awareness is drawn into the body, the principle of Yang predominates. When the awareness is drawn outside away from the body, the principle of Yin predominates. But when the awareness is centered at the nosetip in the breath movements there, the two come into perfect balance and in time are transcended in the passage from duality to unity.

The nosetip is thus the gateway of liberated consciousness as well as the gate of the breath. After a while just putting attention on the nosetip will cause you to move into higher consciousness.

Closing–opening

Just as closing the eyes eliminates a great deal of brain-wave activity, so also merging the attention into the tip of the nose disengages the “machinery” of the mind to a great extent and cuts down on random thoughts. At the same time, however, the higher faculties of intuition become “engaged” and render the meditator capable of true vipassana–intuitive insight.

The breath sensation

We speak of feeling the breath moving at/in the tip of the nose. Just what kind of sensation will that be? Actually, it may be one or more of several sensations: 1) a feeling of the breath moving in a horizontal movement; 2) a feeling of the breath moving in a vertical manner; 3) a feeling of the breath circling inside the tip of the nose; 4) a feeling of the breath collecting in the nosetip and producing a sensation of a gentle pressure. None of these is better than another as they are all simply impressions or interpretations of the nervous system, and completely different sensations may occur than those I have listed. Also, they may change throughout the meditation–even within a single breath. But however that might be, the breath sensations should occur with–and throughout–each inhalation and exhalation, for that is what Buddha meant when he spoke of experiencing the “entire body” of the breath.

The subtle, inner breath has differing sensations also, which arise as you stay aware of the breath at the nosetip. Sometimes the breath seems to be gently vibrating there, stimulating awareness of the nosetip and producing a gentle sensation of expansion and contraction, rising and falling, fullness, pressure, a kind of magnetic pull (first in one direction or pole and then in another direction or pole), or energy movement there–as if the breath were circling or accumulating there. On occasion you may feel that you are pushing and pulling the magnetic flow as it moves in and out.

Sometimes you may just be aware of the breath as a presence at or in the tip of the nose, and not a movement at all. The form in which the breath is felt does not really matter–it is the simple sensation/awareness of the breath at the nosetip that is important.

When the breath becomes subtle

The practice of Breath Meditation refines the breath and transfers the awareness from the outer to the inner breath, from the outer mind to the inner mind, and then to the no-breath and the no-mind: the pure consciousness that is spirit.

This process is very much like the Indian story of the man who was imprisoned at the top of a high tower. To rescue him, his wife came at night with a beetle, a silk thread, a cotton cord, a rope, and some honey. She tied the silk thread to one of the beetle’s back legs, put a drop of honey on its horns, and set it on the side of the tower, pointing straight up toward the window where her husband was waiting. Wanting the honey, the beetle crawled forward, ever forward, until it reached the window and the prisoner, who untied the thread and held on to it. His wife then tied the cord to the silk thread, and her husband pulled it up. Finally she tied the rope to the end of the cord and he pulled that up, secured it, and climbed down to freedom. In this parable things went from subtle to gross, but in anapanasati the breath progresses from gross to subtle–and freedom.

Although it is a good thing for the breath to become increasingly refined as you observe it (perhaps it would be more accurate to say that your awareness becomes refined, though the breath does become lighter in character), still you need not attempt to deliberately make this happen, since it is your attention itself that will refine it. Attention is the key.

Sometimes we lose awareness of our breath because it has become subtle and we are, often unconsciously, trying to force it back into the more objective and easily-perceived mode that it was in at the beginning of our meditation. At such times we must consciously “lighten up” in the most literal sense, relax, and just “breathe” our awareness or breath. At the other times we may seem to be just thinking or willing or conceptualizing the breath more than actually breathing. This, too, is right. As already said, the breath can become as light and subtle as the movement of air produced by the wings of a butterfly. This is an extremely important point to keep in mind, for it is easy to assume that the breath movements and sensations have stopped when actually they have progressed to a subtler stage to which we are not accustomed.

Another experience you may have in the subtle levels of the breath is awareness of a perpetual flow of subtle breath either outward or inward, while at the same time the regular inhalation and exhalation keeps on taking place as usual. On occasion this continuous flow comes to the foreground of your awareness and the inhalation and exhalation become more in the background. Or you experience inhalation and exhalation as taking place “inside” the continuous flow. As a rule this continuous movement is outward–a form of perpetual exhalation–but it can also take the form of a continuous inhalation. And you may even become aware of them both simultaneously. Whatever occurs spontaneously is right. Also, you may experience the breath as a stationary presence within which the inhaling and exhaling movements are taking place. All of these are correct when they occur. You come to experience that the breath is much more than you previously understood.

When the breath is “lost”

When you “lose” the awareness of the breath because it becomes so subtle, you can do one of two things: 1) Take one or more deep breaths through the nose (keeping the mouth closed) to re-establish awareness of the breath, and then continue observing it as usual. 2) Make yourself very aware of the tip of the nose (touch it, if you need to), and simply observe what is–or is not–going on there. Usually, after just a few moments this will enable you to again perceive the subtle movement of the breath, but if not, you can simply sit and be aware of the nosetip alone–of the seeming absence of the breath. In time the awareness of the subtle breath will arise and you can keep on observing it as usual. This is because the nosetip itself is an ideal sensor of the subtle breath movements.

When nothing seems to be going on, do not force anything. Just keep your awareness at the nosetip: watching, watching, watching. In time the very subtle breath will be perceived there. No forcing is needed, just observing.

The quality of the breath

When we make ourselves aware of the breath, it begins to become refined and easeful, even joyful, and we enter a much subtler realm of consciousness. As the breath becomes increasingly refined and subtle during meditation it goes through many stages that we experience, most of them basically indescribable because they are so individual and various, and take place beyond the levels where language can go. Some stages produce inner sensations, some evoke various impressions, mental and sensory, and in some stages the breath is experienced as making very subtle, whisperlike sounds–sometimes a kind of glistering or whooshing-shooshing sound. These attributes of the breath reflect our inner state–are a kind of inner mirror.

The quality or texture of the breath must not be tampered with, for it changes according to the quality or condition of the subtle levels of our being. Sensations of shallowness, inhibition, or discomfort in the breath(ing) are signs of the conditions of the inner body and mind–do not resist them or try to change them. Rather be fully aware of them, as your attention to them will itself correct them in time. So no matter how uncomfortable or strange the sensations that arise as we observe the breath (most especially in the beginning of our meditation time), just experience them and let them be what they are. This objective observation will of itself then correct all kinks and the breath will become soothing and easeful. Only by not “touching” it can we straighten it out. That is contradictory, but reality almost always is.

Just as there should be no clinging to name, form, or thoughts in meditation, so also there should be no attempt to produce or eliminate a particular mode of breath sensation. There should be neither an attraction nor an aversion for however it is at the moment–only acceptance and experience of its quality.

Sometimes in Breath Meditation the awareness of the breath and the nosetip can be very strong, almost heavy, as though your awareness is being drawn into a vortex of magnetic energy. At other times it can be extremely light and subtle, with your attention gently resting on/in them like a kind of glow or faint breeze. These two extremes–and any degrees in between–are natural and right.

Experience the whole breath

Do not become spacey and be aware of the breath only minimally or in a vague or abstract way. Be intent on the breath. Neither should you be aware only of the beginning and end of the inhalations and exhalations. Rather, experience the whole breath, the entire flow of the breath sensation at the nosetip. (Actually, it is only possible to experience the whole breath by keeping our awareness at the tip of the nose.)

We are to experience the breath–not the path of the breath. If we follow the breath inside the body and back out, leaving the nosetip, our awareness will become diluted and even scattered. So stay with the nosetip.

The unified breath

We do not try to be aware of any moment between inhalation and exhalation or between exhalation and inhalation. Just the opposite: by keeping our awareness on the real nosetip breath, relaxed and intent on that breath, it becomes smooth, united, and continuous. This is referred to in the Bhagavad Gita (4:29) where it speaks of those who “offer the outgoing into the incoming breath, and the incoming into the outgoing breath.” Buddhist writings on Breath Meditation speak of “joining” or “circling”–the breath spontaneously becoming unified, the in-and-out breaths smooth and continuous without there being any break or pause between inhalation and exhalation, and vice versa. This, too, should happen spontaneously, and not be forced by us trying to make it so.

The two factors of Breath Meditation

For the successful practice of Breath Meditation we need two factors: 1) awareness of the tip of the nose, 2) awareness of the entire movement or energy-flow of the breath there. We need to keep reminding ourselves of this fact. They are the essential ingredients of Breath Meditation, and we should confine our attention to them. If in meditation we feel unsure as to whether things are going right, we need only check to see if these two things are being done and our attention is centered in them. If so, all is well. If not, it is a simple matter to return to them and make everything right. Then the two in time produce a third factor: pure awareness.

Avoiding the gears

In meditation stay away from the gears of the mind. It is the nature of the mind to dance around producing thoughts, impressions, memories, etc., to draw you into the mental machinery which will whirl you around and confuse and misguide you as it has in this life and your previous births beyond number. Stay away.

Therefore we ignore any potential distractions that may arise during meditation. And then they are no longer distractions. So stay with the breath and forget everything else.

Do not let the mind entice you with supposed insight, inspiration, or knowledge of any kind. According to Shankara the practice of meditation “has right vision alone for its goal, and glories of knowledge and power are not its purpose.”

Never come out of meditation to note or write down something. If the inspiration, insight, or idea is really from your higher Self or from God it will come back to you outside of meditation.

Also, during meditation do not engage the mind-gears with words–mantras, prayers, affirmations, and suchlike–for the same thought machine that generates the repetition of mantras and prayers generates all other thoughts. Consequently their repetition keeps the machine engaged and in working condition–and makes us conscious of it instead of our true Self. That is why the Meditation Word should be used only sparingly. The same principle applies to any kind of visualization.

We do not give the mind any mental toys to play with or yogic gimmicks to produce ego-desired results. Even holy thoughts and impressions are unholy if they disrupt the process of meditation. Even the purest thoughts are defilements in the context of Breath Meditation. Silence alone is proper.

It is like when a thief hides in a house or someone goes into a forest to observe the wildlife. When the house is quiet the thief comes out and does his work. If the forest observer sits without moving, in time the forest dwellers will emerge and be seen. In the same way, those who become still will find the mind revealing itself and giving up its hidden contents. A lot goes on, but it does not touch us, nor–if we are wise–do we touch it. And in time the mind of the mind–the spirit–emerges and reveals itself.

One of the great values of breath awareness is its ability to help us live without extraneous thoughts both in and out of meditation.

Experiences and thoughts in meditation: be indifferent

While mindfully experiencing the breath, many things–some of them quite dramatic, impressive, and even enjoyable, as well as inane, boring, and uncomfortable–occur as a side-effect, as Buddha outlined in several sutras. Have no desire to produce or reproduce or avoid any state or experience of any kind, to any degree. Our only interest should be our observation of the breath at the nosetip. Much revealing and release takes place in both the conscious and subconscious minds–and sometimes even the physical body–as the result of watching the breath, and should always be a passively observed process without getting involved in any way. Just as we observe any discomforts in the breath to correct them, in the same way we observe restlessness, the arising of thoughts, and even boredom to straighten out the kinks in the subtle energy levels, some of which are manifesting physically.

Thoughts from the subconscious may float–or even flood–up, but you need only be sure you do not generate (think) any thoughts. But if you forget and do produce some thoughts, just go back to experiencing the breath at the nosetip. The states of consciousness that meditation produces are the only things that matter, for they alone bring us to the Goal.

Just as the mind has gears, so does the body–especially the chakras and kundalini. We need pay no special attention to them. By right meditation we will automatically purify and perfect all the levels (bodies) of our being and the energies of which they are composed. Our inner faculties and forces will spontaneously awaken at the right time. Much phenomena can take place during the process of correction and purification that is an integral part of meditation. When the chakras are being cleansed and perfected, they may become energized, awakened, or opened. In the same way subtle channels in the spine and body may open and subtle energies begin flowing in them. This is all good when it happens spontaneously, effortlessly. But whatever happens in meditation, our sole occupation should be with awareness of the breath.

Entering theSilence

In the practice of Breath Meditation we go deeper and deeper into the breath until we reach the heart of all, which is Silence. Through breath the meditator leads his awareness into the silence of the spirit which is beyond the clamor of the mind and the distractions and movements of the body. The state of silence is produced in our mind by enabling us to center it in the principle of the silent witnessing consciousness. For true silence is not mere absence of sound, but a profound condition of awareness that prevails at all times–even during the “noise” of our daily life. Silence is also a state of stillness of spirit in which all movement ceases and we know ourselves as pure consciousness alone. “Soundless, formless, intangible, undying, tasteless, odorless, without beginning, without end, eternal, immutable, beyond nature, is the Self. Knowing him as such, one is freed from death” (Katha Upanishad 1:3:15).

Visions

Most visions seen in meditation occur because the meditator has fallen asleep and is dreaming. There are genuine visions, actual psychic experiences, that can occur in meditation, but Ramana Maharshi gives the true facts about all visions when he says: “Visions do occur. To know how you look you must look into a mirror, but do not take that reflection to be yourself. What is perceived by our senses and the mind is never the (ultimate) truth. All visions are mere mental creations, and if you believe in them, your progress ceases. Enquire to whom the visions occur. Find out who is their witness. Stay in pure awareness, free from all thoughts. Do not move out of that state” (The Power of the Presence, vol. 3, p. 249).

Buddha was quite explicit about Breath Meditation producing Knowing. There is no need for either words or visions. We will know from the depths of our being. There really is no other way.

“Concentration”

Although in this book you will find the word “concentration,” it is not used in the sense of forcing or tensing the mind. Rather, we are wanting to become aware–that is, attentive–to the fullest degree. The classic Buddhist manual on meditation and the development of consciousness, the Visuddhimagga, defines concentration (steadiness) as “centering the mind evenly, placing it evenly on the object”–which in this case is the nosetip and the breath. And this is accomplished by two things: relaxing and merging. So when we say “concentration” we mean relaxed awareness/attention.

Not just the body, but the mind needs to be relaxed. This relaxation is what most readily facilitates meditation. Think of the mind as a sponge, absolutely full of water. If you hold it in your hand, fully relaxed, all will be well. But if you grip it or squeeze it, water will spray out. If you “hold” the mind in a state of calm relaxation, very few distractions in the form of memories and thoughts will arise. But if you try to force the mind and tense it, then a multitude of distractions will arise.

Natural practice

It is important in meditation to be relaxed, natural, and spontaneous–to neither desire or try to make the meditation go in a certain direction or try to keep it from going in a particular direction. If our meditation is to bring us to our eternal, natural, innate, spontaneous state of spirit-consciousness, it, too, must be totally eternal, natural, innate and spontaneous. Breath Meditation fits this criterion perfectly, for the breath movement occurs in every evolving sentient being. Nothing, then, is more natural than awareness of the breath. It is the key to our inmost Self and its revelation.

That Breath Meditation is truly a natural practice can be seen by the fact that if a person sits silently in a quiet environment, thinking no thoughts but just being relaxed and aware, in time he will become aware of his breathing as the dominant object of his awareness. If he continues being aware of the breath, after a while his focus of awareness will be on the tip of the nose and/or his nostrils. This awareness will continue for as long as he sits in silent observation. In this way each one can “teach” himself Breath Meditation. It is both natural and universal.

A yogic practice which “makes things happen” by arbitrary will is not real yoga, for real yoga brings about everything spontaneously from deep within, from the Self, with no need for lesser volition. It is putting–and keeping–yourself in a position where things start happening of their own accord. So correct meditation practice is never passive or mentally inert. At all times you are consciously and intentionally experiencing the breath, though easeful and relaxed. “He who sees the inaction that is in action, and the action that is in inaction, is wise indeed” (Bhagavad Gita 4:18). Breath Meditation is the natural entry into profound awareness. In Breath Meditation we are not doing, we are BEING.

Never try to make one meditation period be like one before it. Each session of meditation is different, even though it will have elements or experiences in common with other sessions. Do not be unhappy with yourself if sometimes in meditation it seems you are just floating on the top rather than going deep. That is what you need at the moment. Keep on; everything is all right.

Non-doing

Although we will be looking at the Hindu tradition regarding Breath Meditation later, there are some words of Sri Ramana Maharshi that are particularly relevant at this point.

“The Self is not attained by doing anything, but by remaining still and being as we are.”

“He who instructs an ardent seeker to do this or that is not a true Master. The seeker is already afflicted by his activities and wants peace and rest. In other words he wants cessation of his activities.…If activity is advocated, the advisor is not a Master but a killer. He cannot liberate the aspirant; he can only strengthen his fetters.”

“That one should give up all thought and abide as the Self is the conclusion of all religions.”

“What is there to be gained which we do not already possess? In meditation, concentration and contemplation, all we have to do is be still and not think of anything. Then we shall be in our natural state. …the Self is realized not by doing something but by refraining from doing anything, by remaining still and being simply what one really is.”

Observation of the spontaneous breath is not really “doing” at all–it is just being aware. The more we engage in Breath Meditation the more natural and real we become by being increasingly aware of awareness itself. For our essential nature is simple consciousness. Yet our focused awareness allows great change and development to occur–effortlessly.

The truth is that we are constantly working at keeping ourselves bound and ignorant. Like the Red Queen in Through the Looking Glass, we are running frantically just to stay in one place and not move forward and evolve. If we will examine just a single day in our life–or in that of others–we will see that this is true, even though we are usually not aware of it at all. We are constantly frustrating the inner impulse to liberation and diverting it to that which binds. If we will stop, really stop, and let the inherent pattern of our mind–as well as that of the cosmos–come into operation, everything will correct itself and start going in the direction of real growth and evolution. Through Breath Meditation and Breath Awareness the goal will be reached much quicker and easier than we previously thought.

Doing while not doing

On the other hand, the process of Breath Meditation, though done in a relaxed manner and in consonance with the natural movement of the physical breath, is always a deliberate act. Considered in this way it is a practice, something that is done, while from another viewpoint it is doing nothing. Both are true, and this contradiction itself is part of the necessary mental training of meditation, for in time you will be able to consciously function in the (seeming) paradox of higher reality as compared with the flatline mode of consciousness we usually experience.

In the practice of Breath Meditation we are completely relaxed and breathing naturally and spontaneously. Yet, at the same time we are breathing deliberately in the sense that we are doing it with full awareness and intention. When the breath becomes subtle–almost ideational (and in time does become completely ideational)–we become aware that our breathing is fully an act of will, that the breath itself is a movement of our will rather than a mechanical process of the body. In time we come to see that the breath is a movement of consciousness itself.

Even though in Breath Meditation we do not control the breath or concentrate in any particular way–and throughout the practice we simply breathe naturally and pay attention to it–it is in no way a passive practice. Quite the opposite. For we consciously put our attention on the tip of the nose and intentionally make ourselves fully aware of the process of inhalation and exhalation.

Through awareness of the breath you make yourself aware of awareness itself: conscious of consciousness. Thus the only thing you need ever do is observe and experience the breath at the tip of the nose. Though a lot of other things will happen, it will not be your doing, but the natural consequence of meditation itself.

Enlightenment is the revelation of that which has ever been the essential nature of our selves. It has always been present, for it is us, and does not need to be attained, only revealed (or recognized). For this reason correct meditation is simply the dropping of unreality which automatically is a movement into Reality. This is Nirvana–unbinding.

Two views on the nature of meditation–and a third

In India there is a long-standing disagreement on the nature and purpose of meditation. One school of thought considers that definite–and conscious–evolutionary change is necessary for liberation; consequently meditation must be an actively transforming process. The other view is that the only thing needed for liberation is re-entry into our true, eternal nature–that nothing need be done at all except to perceive the truth of ourselves. Obviously their meditation procedures are going to be completely different.

There is, however, a third perspective on the matter which combines both views. It is true, as said at the beginning of this chapter, that “we are ever-free, ever-perfect, but we have forgotten that fact and have wandered in aimless suffering for countless incarnations.” No one is so foolish as to suggest to a person suffering from amnesia that he need not regain his memory since he has not ceased to be who he really is. Obviously, then, something really does have to be done to change this condition. A dirty window need not be changed in nature, but it needs to be cleansed of that which is not its nature for us to see through it. It is the same with a dusty or smudgy mirror. Meditation is the process of cleansing our consciousness.

Shankara puts forth the question, “How can there be a means to obtain liberation? Liberation is not a thing which can be obtained, for it is simply cessation of bondage.” He then answers himself: “For ignorance [bondage] to cease, something has to be done, with effort, as in the breaking of a fetter. Though liberation is not a thing, inasmuch as it is cessation of ignorance in the presence of right knowledge, it is figuratively spoken of as something to be obtained.” And he concludes: “The purpose of Yoga is the knowledge of Reality.”

Vyasa defines liberation in this way: “Liberation is absence of bondage.” (It is also the definition of Nirvana–“no binding.”) Shankara carries it a bit further, saying: “Nor is liberation something that has to be brought about apart from the absence of bondage, and this is why it is always accepted that liberation is eternal.”

Meditation affects our energy-bodies, not our inner consciousness–it reveals our consciousness rather than changes or produces it. The purpose of meditation is liberation, and to this end it affects the energy complex which is the adjunct of our spirit-Self. Because of this, it is only natural and right that thoughts, impressions, sensations and feelings of many kinds should arise as you meditate, since your meditation is evoking them as part of the transformation process. All you need do is stay relaxed and keep with the breath.

The meditator is already in the Self, is the Self, so in meditation he is looking at/into his personal energy-entity in the same way God observes the evolving creation. Right Meditation purifies and evolves the bodies, including the intelligence (buddhi), and realigns our consciousness with its true state, accomplishing the aims of both schools of meditational thought mentioned before.

Hatching the egg

Each person will experience meditation in a different way, even if there are points of similarity with that of others. Also, meditations can vary greatly. In some meditations a lot will be going on, and then in other meditations it will seem as though we are just sitting and coasting along with nothing happening.

When nothing seems to be going on at all, we may mistakenly think we are meditating incorrectly or it just does not work. Actually, meditation produces profound and far-reaching changes in our extremely complex makeup, whether we do or do not perceive those changes. Some meditations are times of quiet assimilation of prior changes and balancing out to get ready for more change. If we are meditating in the way outlined at the beginning of this chapter, we are doing everything correctly and everything is going on just as it should be–every breath is further refining our inner faculties of awareness.

Very early in the scale of evolution sentient beings are born from eggs, so it is not inappropriate to think of our development in those terms. All eggs hatch and develop through heat–this is absolutely necessary, just as it is for the germination of seeds (the eggs of plants). Yoga is called tapasya, the generation of heat, for that very reason. Our meditation, then, is like the hatching of an egg. Nothing may seem to be going on, but life is developing on the unseen levels.

The hatching of a chicken egg is a prime example. Inside the egg there is nothing but two kinds of goo–the white and the yolk. Both are liquids and have no other perceptible characteristics than color. The hen does nothing more than sit on the egg and keep it warm, yet as the days pass the goo inside the shell turns into internal organs, blood, bones, skin, feathers, brain, ears, and eyes–all that goes to make up a chicken–just by being incubated, by the hen doing “nothing.” At last a living, conscious being breaks its way out of the shell. No wonder eggs have been used as symbols of resurrection from death into life.

Another apt symbol is the cocoon. The dull-colored, earth-crawling, caterpillar encases itself in a shroud of its own making and becomes totally dormant. Yet, as weeks pass a wondrous transformation takes place internally until one day an utterly different creature emerges: a beautifully colored and graceful butterfly that flies into the sky and thenceforth rarely if ever touches the earth.

The same is true of the persevering meditator and the eventual revelation of his true nature. Through the “heat” of meditation, simple as it is, our full spiritual potential will develop and manifest in us. Meditation evolves the meditator, turning the “goo” of his present state into a life beyond present conceptions. This is not abstract theory.

Simplicity of practice

The simpler and more easeful the meditation practice, the more deeply effective it is. This is a universal principle in the realm of inner development and experience. How is this? In the inner world of meditation things are often just the opposite to the way they are in the outer world. Whereas in the outer world a strong, aggressive force is most effective in producing a change, in the inner world it is subtle, almost minimal force or movement that is most effectual–even supremely powerful. Those familiar with homeopathic medicine will understand the concept that the more subtle an element is, the more potentially effective it is. In meditation, the lightest touch is usually the most efficient. This being so, the subtle breath movements experienced in meditation are the most powerful, producing the deepest effects.

An incident that took place during one of the crusades illustrates this. At a meeting between the leaders of the European forces and Saladin, commander of the Arab armies, one of the Europeans tried to impress and intimidate Saladin by having one of his soldiers cleave a heavy wooden chair in half with a single downstroke of his broadsword. In response, Saladin ordered someone to toss a silk scarf as light and delicate as a spider’s web into the air. As it descended, he simply held his scimitar beneath it with the sharp edge upward. When the scarf touched the edge, it sheared in half and fell on either side of the blade without even a whisper as he held it completely still.

There are no “higher techniques” of Breath Meditation, but through its regular and prolonged practice there are higher experiences and effects that will open up for the meditator. As time goes on the efficiency of the practice and the resulting depth of inner experience will greatly increase, transforming the practice into something undreamed-of by the beginning meditator–for the change really takes place in the meditator’s consciousness. Practice, practice, practice is the key.

Practical benefits of meditation

Here are four scientific reports about the practical benefits of meditation, the first three being about Breath Meditation specifically:

1. “Everyone around the water cooler knows that meditation reduces stress. But with the aid of advanced brain-scanning technology, researchers are beginning to show that meditation directly affects the function and structure of the brain, changing it in ways that appear to increase attention span, sharpen focus and improve memory. One recent study found evidence that the daily practice of meditation thickened the parts of the brain’s cerebral cortex responsible for decision making, attention and memory. Sara Lazar, a research scientist at Massachusetts General Hospital, presented preliminary results last November that showed that the gray matter of twenty men and women who meditated for just forty minutes a day was thicker than that of people who did not.…What’s more, her research suggests that meditation may slow the natural thinning of that section of the cortex that occurs with age.” (How to Get Smarter, One Breath At A Time, Lisa Takeuchi Cullen. Time, January 16, 2006, p. 93.)

2. “In a study published in the journal NeuroImage, researchers report that certain regions in the brains of long-term meditators were larger than in a similar control group.

“Specifically, meditators showed significantly larger volumes of the hippocampus and areas within the orbito-frontal cortex, the thalamus and the inferior temporal gyrus–all regions known for regulating emotions.

“‘We know that people who consistently meditate have a singular ability to cultivate positive emotions, retain emotional stability and engage in mindful behavior,’ said Eileen Luders, lead author and a postdoctoral research fellow at the UCLA Laboratory of Neuro Imaging. ‘The observed differences in brain anatomy might give us a clue why meditators have these exceptional abilities.’

“Research has confirmed the beneficial aspects of meditation. In addition to having better focus and control over their emotions, many people who meditate regularly have reduced levels of stress and bolstered immune systems. But less is known about the link between meditation and brain structure.

“The researchers found significantly larger cerebral measurements in meditators compared with controls, including larger volumes of the right hippocampus and increased gray matter in the right orbito-frontal cortex, the right thalamus and the left inferior temporal lobe. There were no regions where controls had significantly larger volumes or more gray matter than meditators.

“Because these areas of the brain are closely linked to emotion, Luders said, ‘these might be the neuronal underpinnings that give meditators the outstanding ability to regulate their emotions and allow for well-adjusted responses to whatever life throws their way.’” (PhysOrg–May 13, 2009. Source: University of California-Los Angeles)

3. “People who meditate grow bigger brains than those who don’t. Researchers at Harvard, Yale, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have found the first evidence that meditation can alter the physical structure of our brains. Brain scans they conducted reveal that experienced meditators boasted increased thickness in parts of the brain that deal with attention and processing sensory input.

“In one area of gray matter, the thickening turns out to be more pronounced in older than in younger people. That’s intriguing because those sections of the human cortex, or thinking cap, normally get thinner as we age.

“‘Our data suggest that meditation practice can promote cortical plasticity in adults in areas important for cognitive and emotional processing and well-being,’ says Sara Lazar, leader of the study and a psychologist at Harvard Medical School.

“The researchers compared brain scans of 20 experienced meditators with those of 15 non-meditators. Four of the former taught meditation or yoga…the rest worked in careers such as law, health care, and journalism.…During scanning, the meditators meditated; the others just relaxed and thought about whatever they wanted.

“Some had been doing (meditation) for only a year, others for decades. Depth of the meditation was measured by the slowing of breathing rates. Those most deeply involved in the meditation showed the greatest changes in brain structure. ‘This strongly suggests,’ Lazar concludes, ‘that the differences in brain structure were caused by the meditation, rather than that differences in brain thickness got them into meditation in the first place.’

“Since this type of meditation counteracts the natural thinning of the thinking surface of the brain, could it play a role in slowing–even reversing–aging? That could really be mind-boggling in the most positive sense.” (PhysOrg–January 31, 2006. Harvard University. William J. Cromie.)

Another report on this study in the New Scientist, titled “Meditation Builds Up the Brain,” says that “meditating actually increases the thickness of the cortex in areas involved in attention and sensory processing, such as the prefrontal cortex and the right anterior insula.

“‘You are exercising it while you meditate, and it gets bigger,’ she [Sara Lazar] says.…It is further evidence, says Lazar, that yogis ‘aren’t just sitting there doing nothing.’”

4. “There was a study reported at the American Geriatric Association convention in 1979 involving forty-seven participants whose average age was 52.5 years. It found that people who had been meditating more than seven years were approximately twelve years younger physiologically than those of the same chronological age who were not meditating.” (Gabriel Cousens, M.D., Conscious Eating, p. 281.)

Falling asleep in meditation

It is normal for beginning meditators to sometimes fall asleep while meditating, since meditation is relaxing and moves the consciousness inward. Both the body and the mind are used to entering into the state of sleep at such times. After a while, though, you will naturally (and hopefully, usually) move into the “conscious sleep” state, so do not worry. You may find that even though you fall asleep you continue to be aware of the nosetip and the breath.

At the same time, be aware that falling asleep in meditation can be a signal from your body that you are not getting enough sleep. People are different, and some do need more than eight hours’ sleep. You should consider extending your sleep time or taking some kind of nap break during the day. Falling asleep in meditation can also be a symptom of a nutritional lack, an indication of low vitality.

Please do not do such things as shock your body with cold water, drink coffee, and run around a bit–hoping to force yourself to stay awake in meditation. This is not the way. Listen to your body and take care of it. Meditators are not storm-troopers. We are engaged in peace, not war.

Yoga Nidra–“conscious sleep”

The purpose of meditation is the development of deep inner awareness. The Yoga Vashishtha (5:78), a classical treatise on yoga, speaks of the state “when the consciousness reaches the deep sleep state” known in Sanskrit as sushupti. The sage Sandilya in his treatise on yoga, the Sandilya Upanishad, also speaks of “when sushupti is rightly cognized (experienced) while conscious.” Ramana Maharshi also spoke frequently of this yogic state known as yoga nidra–yoga sleep. Although it is described as “dreamless sleep,” it is much, much more, for there is a deepening of consciousness in this state that does not occur in ordinary dreamless sleep.

In deep meditation we enter into the silent witness state, experiencing the state of dreamless sleep while fully conscious and aware. When approaching this state the beginner may actually fall asleep. This is not to be worried about, for such is quite natural, and after a while will not occur. From birth we have been habituated to falling asleep when the mind reached a certain inner point. Now through meditation we will take another turn–into the state of deep inner awareness. Ramana Maharshi said that even if a yogi falls asleep while approaching–or in–yoga nidra, the process of meditation still continues.

So when you have this “awake while asleep” state occur, know that you are on the right track–when it is imageless and thoughtless. “Astral dreaming” during meditation is only dreaming illusion. Not that visions cannot occur during meditation, but it is easy to mistake dreams for visions. Therefore it is wise to value only the conscious sushupti experience in meditation, within which the breath continues to be the focus of our awareness. This is the true superconscious state (samadhi).

Physical distractions