A case study of the Datuk Gong cult in Malacca

WENDY CHOO LIYUN

INTRODUCTION

Datuk Gong is a Sino-Malay spirit cult in Singapore and Malaysia, commonly known as Na-du-gong (拿督公) in Chinese, or Datuk Keramat in Malay. This cult is especially interesting because it demonstrates the influence of localization on Chinese folk religion, which was

first brought into Malaysia by the early Chinese immigrants. The intermixture of Malay belief in keramat worship (or saint worship) with Chinese folk religion in this cult is not only apparent in the name of the cult, of which ‘Datuk’ is a Malay word while ‘Gong’ (公)

is a Chinese honorific title often used for gods, but can also be detected in the different elements of worship involved, such as the iconography, rituals and taboos of the cult. This is not to say Malay keramat worship was adopted wholesale into Chinese folk religion.

In his seminar paper, Cheu Hock Tong noted the similarities and differences in beliefs and practices in the worship of Malay keramat and Datuk Gong as a result of selective adaptations by the Chinese.[1] Only those elements of Malay keramat worship which are similar to

Chinese religious worship or useful in helping the Chinese adjust to the new environment in Malaysia were adopted and ‘sinicized’. By studying the worship of Datuk Gong in Malacca, I hope to demonstrate the many points of congruence between Chinese and Malay culture

that has allowed Chinese folk religion to localize.

However, similarities between the Malay and Chinese folk beliefs could not have led to localization if it did not serve the needs of the Chinese in Malaysia. As noted by Anne Goodrich, “wherever and whenever a man felt a need for assistance, he found a god to help him”

.[2] The cult of Datuk Gong grew out of the needs of the Malaysian Chinese to socialize with the Malay state and society, although there must have been a degree of socialization between the Chinese and Malay community before the creation of Datuk Gong cult. Scholars

have noted how the localization of religion can help in the socialization of different communities, but neglected the fact that interaction of cultures is one of the reasons why localization could occur in the first place. The first part of this paper provides a

general background to the adoption of Malay keramat worship by the Chinese and the similarities between the two belief systems that made adaptation easier for Chinese folk religion. The second part presents the findings of my fieldwork in Malacca, which provides the

materials for my analysis on how the processes of localization and socialization reinforce the strength of each other and become increasingly significant as the overseas Chinese decide to settle in Malaysia.

GENERAL BACKGROUND

Malay folk beliefs and keramat worship

Keramat worship or saint-worship is a legacy of early Sufi Islam which played an important role in the propagation of Islamic mystical teachings through Islamic movements.[3] However, as a result of the interactions between indigenous notions of semangat[4] (soul) and

belief in spirits, with the popular Islamic cult of the saints, the idea of keramat took on a variety of meanings. According to W.W Skeat, keramat is of Arabic origins which can be translated to mean ‘sacred’ when it is used as an adjective to describe men, animals,

plants, stones, etc.[5] However, the word ‘keramat’ takes on different meanings depending on the context. When keramat is used on a person, it implies special sanctity and miraculous power. By itself, keramat refers to a holy place.

In his investigation on Malay magic, Skeat pointed out that “theoretically, keramats are supposed to be the graves of deceased holy men, the early apostles of the Muhammadan faith, the first founders of the village who cleared the primeval jungle, or other persons of

local notoriety in a former age”[6], but many of the keramats were actually in the jungle, on the hills and in groves with no traces of a grave. Skeat also noted that “the reverence paid to them and the ceremonies that are performed at them savour a good deal too much

of ancestor worship to be attributable to an orthodox Muhammadan origin”.[7] Thus, aspects of Malay folk religion, especially the indigenous belief in spirits persisted and became syncretized with Islam in keramat worship.

Indigenous belief in spirits, such as guardian sprits, nature deities and ancestral spirits is based on the idea that man’s well-being and the success of his endeavours are dependent on the disposition of the spirits which inhabit his environment.[8] As a result,

nature spirits who are thought to control the elements of nature are often invoked when land is cleared for cultivation, while guardian spirits of villages (usually the spirit of an ancestor or the founder of a settlement) are worshipped to ensure the well-being of the

village. Indigenous belief in spirits became incorporated into keramat worship, such that any person who have done good deeds and contributed to the peace and prosperity of the community may be honoured and remembered after their death as keramats. For all keramats, an

association with Islam is claimed or implied. As a result, religious behaviour towards objects and spirits identified as keramat takes on some Islamic features.[9]

Chinese folk beliefs and Datuk Gong

The similarities between Malay folk beliefs and Chinese folk religion can been seen in Chinese ideas regarding the deification of man, ancestor worship and spirit worship. According to Anne Goodrich, Chinese believe that every person had within him a shen[10] (神) and

if it was strong enough, the person might become a god.[11] Therefore, many Chinese gods are either deified men or nature spirits.[12] Some Chinese also worshipped inanimate things such as stones and sacred trees as gods.[13] Like the Malays, Chinese practised ancestor

worship because they believed in mutual dependence between the living and their dead ancestors.[14] Chinese belief in afterlife meant that the deceased needed the same things as they had when they were alive, including food, clothing, money, etc. If the needs of the

ancestors are provided, they will help and protect their descendants, by providing them with longevity, wealth and success. If their needs are neglected or forgotten, the ancestors will be angry and punish their descendants.

These points of congruence in Malay and Chinese culture made it easier for the Malaysian Chinese to adopt keramats as their deities. Many Chinese visited these shrines of Malay saints. As resurgences of Islamic orthodoxy became increasingly widespread, Malay Muslims

were urged by the state to return to the pure form of Islam whereby Allah is the only God. Consequently, many Malays gave up keramat worship. In these cases, these shrines of supposed Malay origin were adopted by the Chinese: “Some of them (the keramat shrines) were

taken over by the less orthodox Malay Muslims from Hindu antecedents and given an Islamic character. Then in turn they were virtually taken over by the Chinese, and their continuation has come to depend almost entirely on Chinese patronage”[15]

It is believed that the Straits-born Chinese, descendants of the early Chinese immigrants who intermarried with local Malays, took the lead in worshipping the keramat before other Chinese follow suit.[16] The Straits Chinese are familiar with both Malay and Chinese culture, though they saw themselves as more Chinese than Malay. The interactions between early Chinese and Malays probably provided the basis for localization of Chinese folk religion. The Straits Chinese termed the keramat ‘Datuk Gong’.

The term “Datuk” has three possible meanings.[17] For the Straits Chinese, ‘Datuk’ means ‘god’. ‘Datuk’ can also be interpreted as an honourific title, just like the Chinese word ‘Gong’(公). Lastly, the word ‘Datuk’ can be interpreted in Malay as ‘grandfather’. The

Straits Chinese pray to the Malay spirits at these shrines just as they pray to any Chinese deity, with joss sticks and candles. In addition, the Muslim food taboo for pork is observed. Where there is a Malay care-taker, the Chinese worshippers would ask the caretaker

to pray according to the Islamic way and a small donation is given for the service.[18] Datuk Gong became a generic term for the cult of a venerated deceased person, usually of Malay or native origin, or the spirit-being guarding a particular sacred place, either known

or unknown in local history or legend.[19]

FIELDWORK ON DATUK GONG CULT IN MALACCA

Introduction

My fieldwork is based upon interviews with some Chinese I met in Jonker Walk and Bukit Cina area, as well as some Straits Chinese families living in other parts of Malacca. The devotees that I interviewed come from all walks of life: temple committee members, hawkers

at food centres, the shopkeeper of a store that sells Chinese worship items and idols along Jalan Tokong, a hairdresser, an office girl at a Chinese company, clan association members and even the men on the streets. For my fieldwork, I visited Datuk Gong shrines

located within and outside Chinese-owned shops, in residential areas, along the road, under a tree as well as within a temple. Due to time constraint, I only took three trips to Malacca, each lasting 2-3 days and missed the chance to observe the consultation sessions

for Datuk Gong conducted by spirit-mediums.[20]

Many of the Chinese in Malacca know about the existence of Datuk Gong, even if they do not worship him. When I conducted fieldwork in Malacca at the Bukit Cina area and asked around for directions to Datuk Gong shrines, I was told that Datuk Gong shrines can be found

all over the place and the Chinese recommended me to the ones that they felt were ling(灵) or spiritually potent. None of my interviewees seemed to know about the origins of Datuk Gong. They were simply continuing the tradition of their parents and saw no need to learn

about the origins of the deity as long as he is ling.

Although Datuk Gong is a Sino-Malay cult, Malays and Chinese are not the only ethnic groups that worshipped Datuk Gong. Many Indians are involved in the worship. Devotees mentioned that Indian spirit-mediums are sometimes engaged to conduct consultation sessions for

Datuk Gong and many Indian grocery shops sell the offerings prepared specially for the worship of Datuk Gong. Some Datuk Gongs are even of Indian Muslim origins.

Like most Chinese gods, Datuk Gong is a title of an office which can be held by one person or another. The office can continue through the years but the position could be held by one spirit in one part of the country and by another elsewhere. Thus, the Datuk Gong in

different locations can have different names, different birthdays and different personality traits. However, the birthdays of all Datuk Gong are dated according to the Chinese lunar calendar and are revealed to the devotees through the spirit-medium or through dreams.

For example, one Datuk Gong that I visited is known as Dato Waji Wahid, his birthday being on the 16th day of the eighth lunar month.[21] When I asked the owner how she knew when the birthday of the deity was, she told me that she had hired a spirit-medium to find out.

Dato Waji Wahid is also said to have been to Mecca and is Haji.

There are also female versions of Datuk Gong, known as Datuk Nenek (or Na-du-nai-nai 拿督奶奶). Nenek is the Malay word for “grandmother”. When praying to the Datuk Nenek, some of the devotees actually offered her cologne (gu-long-shui 古龙水) and make-up, reflecting the

Chinese belief in afterlife and the humanistic nature of gods.

Datuk Gong is said to possess different personality traits. Some of my informants depicted Datuk Gong as benevolent, helping devotees recover from illnesses which even a trained doctor could not heal. Others warned against reckless worship of the Muslim deity, for he

is strict towards his worshippers, punishing those who are disrespectful and pray to him without refraining from eating pork.

While some Datuk Gong have Muslim names, the more common ones are those with the names of colours such as Datuk Merah (Red Datuk), Datuk Kuning (Yellow Datuk) and Datuk Putih (White Datuk). This could be due to Malay traditions that seldom refer to indigenous spirits

by their specific names.[22] According to Cheu Hock Tong, each of the colours symbolizes the function of each Datuk Gong. Green signifies the keramat of the east who ensures the growth of flora and fauna; red refers to the keramat of the south who controls drought,

fire and harvest; white represents the keramat of the west who is in control of ill-luck or inauspiciousness, black represents the keramat of the north who exercises control on water, flood and death; and yellow refers to the keramat of the centre who keeps

surveillance over the stability and general well-being of the respective colours.[23] Interestingly, this also seems to reflect the influence of the Five Element, Five Colours and Five Directions in Chinese cosmology.[24]

However, this is not to say Datuk Gong of particular colour is limited to a certain function. My interviews with local devotees showed that Datuk Gong performs multiple roles, as god of health, god of wealth, god of earth and even exorcists to different people who

sought his help.

What do the worshippers pray for?

The Chinese worshipped Datuk Gong in the belief that the he has the power to preserve peace, harmony and safety in both residential areas and factories. An interviewee revealed that most Chinese factories would erect Datuk Gong shrines at their work-sites or compounds

and worship him in the morning and at night everyday to ensure smooth running of the business, especially if the land on which the factories are built have been newly reclaimed from forested areas or uninhabited land. Another devotee claimed that at least 80% of the

Chinese businessmen who owned factories have an altar devoted to Datuk Gong at their work sites. Even though his claim might have been exaggerated, the popularity of Datuk Gong in Chinese-owned factories in Malacca is a fact verified by all my interviewees.

Many Chinese believe that Datuk Gong can enrich them by revealing lucky numbers or conferring lucky draws in lottery. Many of the devotees that I interviewed were quick to introduce me to the Datuk Gong shrines that that they thought were most ling and answered their

requests for lucky numbers. In exchange for the help, the devotees would vow to provide the deity with a feast or to refurnish the shrines of the deity should they strike lottery.

Datuk Gong can also help the Chinese get better if he is possessed by evil Malay spirits or is put under a Malay spell. When I asked whether a Chinese deity could do the job, my informant replied that a Malay deity is better because he is closer culturally and can

communicate more effectively with the Malay spirits.

Shrines and temples

The choice of installing or worshipping the Datuk Gong in the home or in factories is usually due to a premonition the worshipper has, the recommendations of a spirit-medium employed by the worshipper, or a dream from Datuk Gong to the worshipper asking to be

venerated. Reflecting the Chinese primary concern with practical benefits, if the Datuk Gong of any shrines proved to be lacking in potency after worship, the shrine is often allowed to fall into a state of disuse.

A devotee told me the story about the Datuk Gong shrine near her house: the residents wanted to build a temple at the site so they invited the spirit mediums to check out if other spirits or gods resided at the location. They were told that a Datuk Gong stayed there

and had asked to be worship along with the Chinese gods in the temple. The acknowledgement of being newcomers to an ‘occupied’ land led the Chinese to worship the Malay spirit.

Scholars such as Cheu Hock Tong and Tadao Sakai believe that Datuk Gong is the Malay equivalent of the Chinese Tu-di (土地), or the local God of Earth because Datuk Gong shrine is based on the format of traditional Chinese locality deities.[25] An informant brought me

to a shrine dedicated to seven Datuk Gong and a Tua-pek-gong (大伯公). The fact that the shrine is called Di-zhu-gong-ting (地主公亭)[26], or the Shrine of Earth Gods is reflective of the position the Sino-Malay deity is thought to hold within the Chinese pantheon.

In Malacca, although the worship of Datuk Gong is very popular, there are few big Chinese temples that are solely dedicated to the worship of Datuk Gong. Instead, Datuk Gong is frequently the subsidiary god in Chinese temples or is placed outside the main altar of the

temple at a small isolated shrine within the temple grounds. An informant revealed that the Datuk Gong is seldom placed along the same altar as other Chinese gods in the temple because of the restriction he had due to his Muslim identity.

On the occasions when Datuk Gong is worshipped in big Taoist temples, he is usually placed with Tua-pek-gong. In Di-zhu-gong-ting, where Datuk Gong share the same altar with the Chinese Tua-pek-gong, the seven Datuk Gong were placed close together and shared a censer,

while Tua-pek-gong was distanced from the seven Datuk Gong and had a separate censer to himself.[27] Thus, a clear divide between Datuk Gong and other Chinese deities existed even when they were placed on the same altar.

For those who worshipped Datuk Gong in their homes, the altar for Datuk Gong is usually set in a small shrine in the backyard. There are also some devotees who placed the altar for Datuk Gong under their ancestral tablets or the tablets of higher-ranking Chinese god.

Although building altars are usually located in the front corners or at the back of Chinese houses, shops, factories or temples, fengshui (风水) sometimes plays a role in the site of the altar, especially for those who set up the altars in factories or at home. For

instance, an informant who is a member of a temple committee in Malacca pointed out that the altar of Datuk Gong at the back of the coffee-shop where I met him faces the entrance of the shop because the other directions either face Bukit Cina (the hill of the dead),

which is inauspicious, or the wall. He also mentioned that sometimes, Datuk Gong would choose his preferred location for the altar by appearing in the dreams of devotees or by voicing his request through a spirit-medium.

As a result of the interactions between Malay culture and Chinese folk religion, some Datuk Gong shrines are constructed with Islamic motifs, such as the crescent, or Malay architectural designs.[28] Yellow is often used for the colour of the roof in Datuk Gong shrines

and a yellow cloth is often hung on the shrines of Datuk Gong.[29] The colour yellow is seen in the Malay concept of divine kingship as the sole prerogative of the royalty and prohibited among the commoners, thus it creates an aura of sanctity and respect from the

people when it is used on the keramat.[30] Coincidentally, yellow was also the symbolic colour of the royalty in traditional China.

Iconography

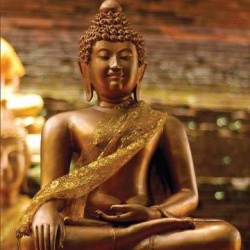

Chinese worshippers believe that if one has the picture or image of the deity, or a piece of paper or wood with the name of the deity written on it, the soul, mind and personality of the deity would be present. In local Chinese religious iconography, Datuk Gong is

commonly represented by a Malay man dressed in traditional Malay shirt and sarong, wearing a formal songkok (hat).[31] Kris (Malay sword) and other traditional Malay court regalia and ceremonial objects would also be placed on the altar.

According to a devotee, the iconography of Datuk Gong can also be distinguished by its colour. The idol of the Green Datuk Gong is usually made holding a rattan (木藤), the Red Datuk with a snake, the White Datuk with taels (元宝), the Black Datuk with a tongkat

(walking stick) and the Yellow Datuk with a kris. However, since Malay Datuk Keramat often dies by a sacred stone or transform into a stone upon death, and there are state restrictions on the use of Islamic iconography in Chinese temples and shrines, many people

preferred to use stones rather than idols to represent the deity.[32] In these cases, a stone wrapped with certain coloured cloth, or a piece of red paper with Na-du-gong (拿督公) written on it would be used as a representation of the deity. Sometimes, a tablet with the

Na-du-gong carved onto it is used to represent the deity.[33]

Rituals

Each Datuk Gong shrine is represented by an altar, which is often signaled by the presence of a censer. Each censer usually embodies a Datuk Gong spirit. Worship of Datuk Gong is typical of Chinese practices, involving bows and prostrations with folded hands, burning

of spirit money, prayers and vows, and Chinese ritual paraphernalia such as incense and candles. However, in the Datuk Gong shrines in Malacca, yellow candles instead of red or white candles are often used.[34]

Offerings of fruits are often served to the deity. Bananas are commonly used as offerings for Datuk Gong, because they symbolize gold and sticky glutinous rice symbolizes riches and togetherness to the Chinese.[35] Pineapples are also typical worship item. Known as ong-

lai in Hokkien, pineapple represents prosperity and is always used by Hokkiens in their worship of Heaven during Chinese New Year.[36]

Malay usually forms the language of communication between the Datuk Gong and the Malaysian Chinese devotees. An interviewee believe that praying to the deity in Malay made the deity more accessible and more responsive to her requests, although one can pray to the deity

in any language. Moreover, Datuk Gong speaks Malay when he possesses a spirit-medium and writes charms for his devotees in Malay.

Other than typical Chinese ritual paraphernalia, Malay worship items are also incorporated. In Malacca, one can pay one ringgit to an Indian Muslim grocery store to get the worship items for Datuk Gong, commonly known as the Datuk liao[37] (拿督料). The items include

shredded tobacco or native cigarette (rokok daun)[38], arecanut flakes and betel leaves with lime paste. The betel leaf is of great significance to the Malays, having ritual powers which can cure the sick of their diseases. Some other Malay offerings include pulut

kunyit (yellow-stained glutinous rice) and bunga telur (red-coloured eggs). Offering the pulut kuning which is actually glutinous rice stained with tumeric to the keramat implies that the individual is according great respect to the saint and thus hopes that his/her

request would be fulfilled.[39] The offering of benga telur is meant to appease the spirit of the ancestors and protect the devotee from any form of attack by evil spirits. The Malay practice of strewing sweet scented flowers over the graves of the keramat to

demonstrate the respect of devotees towards the saint is also used by the Chinese in the worship of Datuk Gong. .

According to an informant, the important days (大日子) of worship in Malacca are Thursday and Fridays. These are the days when rituals or prayers will be performed for Datuk Gong. One Taoist temple that I visited has consultation sessions for Datuk Gong devotees every

Thursday evenings. Scholars have also noted the significance of Thursday to the Malay community.[40] The Chinese devotees usually pray to Datuk Gong in the mornings, before any meat is taken or at night. A devotee also mentioned that in some Datuk Gong temples in

Malaysia, Islamic festivals such as Hari Raya Haji or Hari Raya Puasa are celebrated.

Taboos

According to informants, worshippers should never serve Datuk Gong with pork or it will incur his wrath and the devotee will be punished. For stricter Datuk Gong, devotees are not allowed to pray to him if they had pork for their meal just before they visit to him. If

a female devotee is having her period, she is seen as ‘dirty’ and forbidden from touching the deity, especially his head.

INTERPRETATION AND ANALYSIS

Parsons have noted that religion, as a set of beliefs, practices and institutions, evolve in various societies as responses to different aspects of their life and situation.[41] Graham also pointed out how Chinese have always used religion to understand and make sense

of the environment around them.[42] The practicality of Chinese folk religion and its pervasiveness back in China ensured its survival even after it was exported to Malaya[43]. Chinese folk religion is then utilized by the Chinese immigrants to cope with the alien

social environment as individuals reconstructed their community and culture by actively adapting ancient symbols and ritual forms to suit the local environment. Therefore, by studying the Datuk Gong cult, we can find out how localization of Chinese folk religion helped

the immigrant Chinese adapt to their new environment and how their early socialization with the Malay community is reflected in the cult.

An understanding of the meanings of the Malay term ‘Datuk’ can give us a peek into the different ways Datuk Gong cult reflected the early contacts between Chinese and Malays in Malaya. By understanding the term ‘Datuk’ as grandfather, the Chinese can be said to be

praying to the ancestors of the Malays. In the incorporation of Malay keramat worship into Chinese folk religion, the Chinese immigrants demonstrated their acknowledgement of Malay authority over their community by showing respect towards the Malay ancestors. As noted

in my fieldwork, Chinese businessmen with factories and worksites in previously uninhabited areas and Chinese who wished to build a temple on any sites would usually employ a spirit-medium to find out if any Malay spirits such as Datuk Gong occupied the area. If the

area was ‘occupied’, the Chinese would usually try to maintain a harmonious relationship with the spirit by granting their wishes, in the hope that the spirits would help them in their business endeavours. In syncretizing the Chinese God of Earth with Malay local

spirits, immigrant Chinese entrepreneurs extended recognition and respect to the original spiritual protectors of a land that yielded them great wealth.[44]

If we see the term ‘Datuk’ as an honorific title granted by the sultans to people of great contributions to the community or state, Datuk Gong becomes a symbol of Malay political authority. The fact that Datuk Gong is worshipped by the Chinese as the local God of Earth

with jurisdiction over a certain area further reinforces the role of Datuk Gong as the Malay district officer representative of the state. In this way, the Malay state is engaged as a cultural idea by the Chinese immigrants in the body of Datuk Gong, a Malay honorific

figure representative of the state who helps the Chinese immigrants residing on their land by answering their prayers for prosperity and peace.

Interactions between Chinese businessmen and the Malay rulers were necessary to ensure profitability and convenience in trade. Historically, the Chinese immigrants had always been confined to the economic sector while the Malays dominated the political sphere. Chinese

businessmen sought state protection and maintenance of peace and stability, or economic benefits such as tax concessions. In return, they rewarded the help of Malay rulers by offering other benefits, such as sharing of monetary favours in terms of loans and giving the

rulers their political allegiance. The reciprocal relationship between the Malay rulers and Chinese immigrants is reflected in the cult of Datuk Gong. Many Chinese pray to Datuk Gong for economic benefits, such as lucky numbers or for the success of their economic

ventures. When their wishes are granted, they fulfill their vows to the deity by preparing a feast or rebuilding the shrine for the deity. On the other hand, if Datuk Gong does not prove to be responsive to the needs of his devotees, his shrine is allowed to fall into

disuse as devotees turn to other more powerful Datuk Gong.

The fact that Datuk Gong punishes his devotees if they violated his taboos serves as a reminder to the Chinese that Islam and Malay traditions are important features of Malay life that could easily upset the Malay rulers and community if due respect was not given. As

more and more Chinese decided to settle on the Malay land, interactions with Malay community also took on additional importance. With the disintegration of the sojourner mentality, ethnic enclaves no longer prove to be a viable option. Instead, contacts with the Malay

community became unavoidable and essential to ensure profitability in trade and to lead a peaceful life.

One way to attain this harmonious relationship was by promoting an understanding of Malay customs, beliefs and taboos to other Chinese settlers whose contacts with the Malays are still limited. This was aided by the incorporation of Malay keramat worship into Chinese folk religion. In this way, the early Chinese settlers could pass down their knowledge of Malay taboos and needs by socializing other Chinese with Malay culture through the cult. The separation of Datuk Gong from other Chinese deities in Chinese temples showed that

being Muslim, his needs had to be catered for through a different system of worship comprising of both Malay and Chinese elements. Therefore, the Chinese settlers are prompted that Muslims lead a different way of life that Chinese must respect.

While localization is partly the result of socialization, localization can also reinforce socialization. Other than promoting greater understanding of Malay beliefs, Datuk Gong cult can also help the Chinese to develop actual relations with the Malay community. For

example, the birthday of Datuk Gong serves as occasion for communication and cooperation between the Chinese and Malays, since Malay help has to be sought to prepare halal food for the Muslim deity. In addition, through the Datuk Gong cult, Chinese can demonstrate

their acceptance and understanding of Malay culture to the Malay community by respecting the taboos of the Datuk Gong, and by participating in Malay festivals such as Hari Raya. Even though the contacts between the Malay and the Chinese communities may be superficial

at sight, an understanding of the customs and practices of the indigenous people must have reduced the opportunities for cultural conflicts and helped the early Chinese immigrants feel more at ease in their new home.

However, the incorporation of Malay and Islamic elements into Chinese folk beliefs does not mean that the Malaysian Chinese are ‘masuk Malay’ (becoming Malay). In the sense that religious systems allow channels for expression of community, Chinese religion is an

element in the expression of Chinese ethnicity. As noted by John Clammer, while Chinese popular religion is “an adaptive set of strategies for coping with both the changing world and its unchanging basis–people’s relationship to life, death and the supernatural”, it

also provides an identity-confirming mechanism which links the Malaysian Chinese to “the great body of traditional Chinese cultural themes so easily lost by an immigrant people.”[45] Rather than “masuk Malay”, the acculturation of Chinese folk religion produced a

distinct cult that enabled Chinese in Malaysia to develop a cultural identity that tied them to their ancestral homeland, while allowing them to develop a sense of identification to the Malay land in which they now reside. Thus, even though Datuk Gong is a Malay deity,

he is seen as part of the Chinese pantheon, indicating how the Malaysian Chinese continue to identify themselves with their Chinese roots despite the acculturation with Malay beliefs.

CONCLUSION

My fieldwork showed that Malay folk beliefs were clearly incorporated into Chinese folk religion in the cult of Datuk Gong. What had allowed localization to occur were not only the similarities between the two cultural systems, but also because a Sino-Malay deity

served the needs of the Chinese. The fact that Chinese were more concerned about the potency of the deity than his ethnicity points to the pragmatism of the Chinese. Earlier socialization with Malay state and society provided the basis for localization. Coupled with

the adaptability of Chinese folk religion, it was no surprise that Chinese religion became an important tool for the Chinese to socialize with the Malay community by demonstrating their religious sensitivity towards Malays and encouraging greater understanding of Malay

culture. Localization of Chinese folk religion did not make the Chinese ‘masuk Melayu’, but had allowed the Chinese to preserve their ethnic identity by retaining their culture and traditions, while helping the early Chinese immigrants adapt to their residence in the

Malay world.

Interestingly, Datuk Gong shrines cannot be found in the Chinatown of Malacca (specifically the Jonker Walk area) where famous Chinese temples such as Cheng Hoon Teng (青云亭) are located. Within the Jonker Walk area, there is a strong sense of Chinese identity

fostered by the presence of the clan associations and temples. Many of the images of Chinese deities in the temples were specially imported from China. On the other hand, Datuk Gong shrines are more prevalent in the Bukit Cina area, which lies on the periphery of

Chinatown and is closer to other Malay towns. This observation reveals how the process of localization was accelerated as more and more Chinese immigrants decided to settle in Malaysia and out of their traditional ethnic enclaves, when contacts with the Malay community

and state became more regular and essential. However, it should be noted that the extent to which the cult of Datuk Gong can help maintain harmonious ethnic relations between the Chinese and Malays may be limited by steps taken by the government against the use of

Islamic signs and symbols in Chinese temples.[46]

REFERENCES

Abdul Wahab Bin Hussein Abdullah. “A Sociological Study of Keramat Beliefs in Singapore”. B.A Honours Academic Exercise, Department of Sociology, National University of Singapore, 2000.

Andaya and Andaya, Barbara Watson and Leonard. A History of Malaysia. Honolulu, University of Hawaii Press, 2001.

Cheu, Hock Tong. “The Datuk Gong Spirit Cult Movement in Penang: Being and Belonging in Multi-ethnic Malaysia”. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, vol. 23, no. 1 (September), 381-404.

Cheu, Hock Tong. “Malay keramat, Chinese worshippers: The Sinicization of Malay Keramats in Malaysia”. Seminar paper, Department of Malay Studies, National University of Singapore, 1994.

Cheo, Kim Ban and Muriel Speeden, Baba Folk Beliefs and Superstitions. Singapore: Landmark Books, 1998.

Clammer, John ed. Studies in Chinese folk religion in Singapore and Malaysia. Singapore: Contributions to Southeast Asian ethnography, 1983.

DeBernardi, Jean. Rites of belonging: memory, modernity and identity in a Malaysian Chinese community. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2004.

Elliott, Alan J.A. Chinese Spirit-Medium cult in Singapore. Singapore: Donald Moore, 1964.

Goodrich, Anne. Peking paper gods: a Look at Home worship. Nettetal: Steyler Verlag, 1991.

Graham, David Crockett. Folk Religion in southwest China. Washington, Smithsonian Institution, 1961.

McHugh, J.N. Magic in Names and Other Things (London: Chapman Hall, 1920), 157.

Lessa , William A. et al., Reader in Comparative Religion: An Anthropological Approach. New York, Harper and Row, 1965.

Mohd Taib Osman, Malay folk beliefs: An integration of disparate elements. Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, 1989.

Ng, Siew Hua, “The Sam Poh Neo Neo Keramat: A Study of a Baba Chinese Temple”. Contributions to Southeast Asian Ethnography, vol. 25, pt. 1, 1983, 175-177.

Skeat, W.W. Malay Magic. London: MacMillan, 1900.

Tan, Chee Beng. The Baba of Melaka. Selangor, Pelanduk Publications, 1988.

Tjandra, Lukas. Folk religion among the Chinese in Singapore and Malaysia (Ann Arbour, Michigan: University Microfilms International, 1990), 48.

The Straits Times, Johor Committee submits report on Houses of Worship, 29 Dec 1989.

The Straits Times, Stop Use of Muslim Signs, Chinese temples Told, 25 June 1987.