Vinaya Pitaka

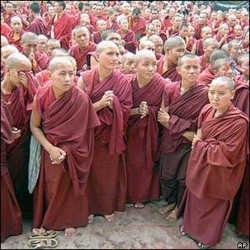

Vinaya Pitaka : The Vinaya Pitaka, the first division of the Tipitaka, is the textual framework upon which the monastic community (Sangha) is built. It includes not only the rules governing the life of every Theravada bhikkhu (monk) and bhikkhuni (nun), but also a host of procedures and conventions of etiquette that support harmonious relations, both among the monastics themselves, and between the monastics and their lay supporters, upon whom they depend for all their material needs.

When the Buddha first established the Sangha, the community initially lived in harmony without any codified rules of conduct. As the Sangha gradually grew in number and evolved into a more complex society, occasions inevitably arose when a member would act in an unskillful way. Whenever one of these cases was brought to the Buddha's attention, he would lay down a rule establishing a suitable punishment for the offense, as a deterrent to future misconduct. The Buddha's standard reprimand was itself a powerful corrective:

It is not fit, foolish man, it is not becoming, it is not proper, it is unworthy of a recluse, it is not lawful, it ought not to be done. How could you, foolish man, having gone forth under this Dhamma and Discipline which are well-taught, [commit such and such offense]?... It is not, foolish man, for the benefit of un-believers, nor for the increase in the number of believers, but, foolish man, it is to the detriment of both unbelievers and believers, and it causes wavering in some.

— The Book of the Discipline, Part I, by I.B. Horner (London: Pali Text Society, 1982), pp. 36-37.

The monastic tradition and the rules upon which it is built are sometimes naïvely criticized — particularly here in the West — as irrelevant to the "modern" practice of Buddhism. Some see the Vinaya as a throwback to an archaic patriarchy, based on a hodge-podge of ancient rules and customs — quaint cultural relics that only obscure the essence of "true" Buddhist practice.

This misguided view overlooks one crucial fact: it is thanks to the unbroken lineage of monastics who have consistently upheld and protected the rules of the Vinaya for almost 2,600 years that we find ourselves today with the luxury of receiving the priceless teachings of Dhamma. Were it not for the Vinaya, and for those who continue to keep it alive to this day, there would be no Buddhism.

It helps to keep in mind that the name the Buddha gave to the spiritual path he taught was "Dhamma-vinaya" — the Doctrine (Dhamma) and Discipline (Vinaya) — suggesting an integrated body of wisdom and ethical training.

The Vinaya is thus an indispensable facet and foundation of all the Buddha's teachings, inseparable from the Dhamma, and worthy of study by all followers — lay and ordained, alike.

Lay practitioners will find in the Vinaya Pitaka many valuable lessons concerning human nature, guidance on how to establish and maintain a harmonious community or organization, and many profound teachings of the Dhamma itself. But its greatest value, perhaps, lies in its power to inspire the layperson to consider the extraordinary possibilities presented by a life of true renunciation, a life lived fully in tune with the Dhamma.

The Vinaya Pitaka is made up of five books:

- (1) Parajika Pali

- (2) Pacittaya Pali

- (3) Mahavagga Pali

- (4) Culavagga Pali

- (5) Parivara Pali

Parajika Pali

Parajika Pali which is Book I of the Vinaya Pitaka gives an elaborate explanation of the important rules of discipline concerning Parajika and Sanghadisesa, as well as Aniyata and Nissaggiya which are minor offenses.

(a) Parajika offences and penalties.

Parajika discipline consists of four sets of rules laid down to prevent four grave offences. Any transgressor of these rules is defeated in his purpose in becoming a bhikkhu. In the parlance of Vinaya, the Parajika Apatti falls upon him; he automatically loses the status of a bhikkhu; he is no longer recognized as a member of the community of bhikkhus and is not permitted to become a bhikkhu again. He has either to go back to the household life as a layman or revert back to the status of a samanera, a novice.

One who has lost the status of a bhikkhu for transgression of any of these rules is likened to (i) a person whose head has been cut off from his body; he cannot become alive even if the head is fixed back on the body; (ii) leaves which have fallen off the branches of the tree; they will not become green again even if they are attached back to the leaf-stalks; (iii) a flat rock which has been split; it cannot be made whole again; (iv) a palm tree which has been cut off from its stem; it will never grow again.

Four Parajika offences which lead to loss of status as a bhikkhu.

- (i) The first Parajika: Whatever bhikkhu should indulge in sexual intercourse loses his bhikkhuhood.

- (ii) The second Parajika: Whatever bhikkhu should take with intention to steal what is not given loses his bhikkhuhood.

- (iii) The third Parajika: Whatever bhikkhu should intentionally deprive a human being of life loses his bhikkhuhood.

- (iv) The fourth Parajika: Whatever bhikkhu claims to attainments he does not really possess, namely, attainments to jhana or Magga and Phala Insight loses his bhikkhuhood.

The parajika offender is guilty of a very grave transgression. He ceases to be a bhikkhu. His offence, Apatti, is irremediable.

Thirteen Samghadisesa offences and penalties

Samhghadisesa discipline consists of a set of thirteen rules which require formal participation of the Samgha from beginning to end in the process of making him free from the guilt of transgression.

- (i) A bhikkhu having transgressed these rules, and wishing to be free from his offence must first approach the Samgha and confess having committed the offence. The Samgha determines his offence and orders him to observe the parivasa penance, a penalty requiring him to live under suspension from association with the rest of the Samgha, for as many day, as he has knowingly concealed his offence.

- (ii) At the end of the parivasa observance he undergoes a further period of penance, menatta, for six days to gain approbation of the Samgha.

- (iii) Having carried out the menatta penance, the bhikkhu requests the Samgha to reinstate him to full association with the rest of the Samgha.

Being now convinced of the purity of his conduct as before, the Samgha lifts the Apatti at a special congregation attended by at least twenty bhikkhus, where natti, the motion for his reinstatement, is recited followed by three recitals of kammavaca, procedural text for formal acts of the Samgha.

Some examples of the Samghadisesa offence

(i) Kayasamsagga offense:

- If any bhikkhu with lustful, perverted thoughts engages in bodily contact with a woman, such as holding of hands, caressing the tresses of hair or touching any part of her body, he commits the Kayasamsagga Samghadisesa offense.

(ii) Sancaritta offense:

- If any bhikkhu acts as a go-between between a man and a woman for their lawful living together as husband and wife or for temporary arrangement as man and mistress or woman and lover, he is guilty of Sancaritta Samghadisesa offense.

(c) Two Aniyata offenses and penalties

Aniyata means indefinite, uncertain.

There are two Aniyata offences the nature of which is uncertain and indefinite as to whether it is a Parajika offence, a Samghadisesa offence or a Pacittiya offence. It is to be determined according to provisions in the following rules:

- (i) If a bhikkhu sits down privately alone with a woman in a place which is secluded and hidden from view, and convenient for an immoral purpose and if a trustworthy lay woman (i.e., an Ariya), seeing him, accuses him of any one of the three offences

(1) a Parajika offence

(2) a Samghadisesa offence

(3) a Pacittiya offence,

and the bhikkhu himself admits that he was so sitting, he should be found guilty of one of these three offences as accused by the trustworthy lay woman.

- (ii) If a bhikkhu sits down privately alone with a woman in a place which is not hidden from view and not convenient for an immoral purpose but convenient for talking lewd words to her, and if a trustworthy lay woman (i.e., an Ariya), seeing him, accuses him of any one of the two offences

1) a Samghadisesa offence

(2) a Pacittiya offence,

and the bhikkhu himself admits that he was so sitting, he should be found guilty of one of these two offences as accused by the trustworthy lay woman.

(d) Thirty Nissaggiya Pacittiya offences and penalties

There are thirty rules under the Nissaggiya category of offences and penalties which are laid down to curb inordinate greed in bhikkhus for possession of material things such as robes, bowls etc.

To give an example, an offence is done under those rules when objects not permitted are acquired, or when objects are acquired in more than the permitted quantity. The penalty consists firstly of giving up the objects in respect of which the offence has been committed.

Then it is followed by confession of the breach of the rule, together with an undertaking not to repeat the same offence, to the Samgha as a whole, or to a group of bhikkhus, or to an individual bhikkhu to whom the wrongfully acquired objects have been surrendered.

Some examples of the Nissaggiya Pacittiya offences.

(i) First Nissaggiya Sikkhapada.

- If any bhikkhu keeps more than the permissible number of robes, namely, the lower robe, the upper robe and the great robe, he commits an offence for which he has to surrender the extra robes and confess his offence.

(ii) Civara Acchindana Sikkhapada.

- If any bhikkhu gives away his own robe to another bhikkhu and afterwards, being angry or displeased, takes it back forcibly or causes it to be taken away by someone else, he commits a Nissaggiya Pacittiya offence.

Nissaggiya offences are light offences compared with the grave offences of Parajika Apatti or Samghadisesa Apatti.

2. The Pacittiya Pali

The Pacittiya Pali which is Book II of the Vinaya Pitaka deals with the remaining sets of rules for the bhikkhus, namely, the Pacittiya, the Patidesaniya, Sekhiya, Adhikaranasamatha and the corresponding disciplinary rules for the bhikkhunis. Although it is called in Pali just Pacittiya, it has the distinctive name of 'Suddha Pacittiya', ordinary Pacittiya, to distinguish it from Nissaggiya Pacittiya, described above.

(a) Ninety two Pacittiya offences and penalties

There are ninety two rules under this class of offences classified in nine sections. A few examples of this type of offences:

- (i) Telling a lie deliberately is a Pacittiya offence.

- (ii) A bhikkhu who sleeps under the same roof and within the walls along with a woman commits a Pacittiya offence.

A Pacittiya offence is remedied merely by admission of the offence to a bhikkhu.

(b) Four Patidesaniya offences and penalties

There are four offences under this classification and they all deal with the bhikkhu's conduct in accepting and eating alms-food offered to him. The bhikkhu tranagressing any of these rules, in making admission of his offence, must use a special formula stating the nature of his fault.

The first rule of Patidesaniya offence reads: should a bhikkhu eat hard food or soft food having accepted it with his own hand from a bhikkhuni who is not his relation and who has gone among the houses for alms-food, it should be admitted to another bhikkhu by the bhikkhu saying, "friend, I have done a censurable thing which is unbecoming and which should be admitted. I admit having committed a Patidesaniya offence."

The events that led to the laying down of the first of these rules happened in Savatthi, where one morning bhikkhus and bhikkhunis were going round for alms-food. A certain bhikkhuni offered the food she had received to a certain bhikkhu who took away all that was in her bowl. The bhikkhuni had to go without any food for the day. Three days in succession she offered to give her alms-food to the same bhikkhu who on all the three days deprived her of her entire alms-food. Consequently she became famished. On the fourth day while going on the alms round she fainted and fell down through weakness. When the Buddha came to hear about this, he censured the bhikkhu who was guilty of the wrong deed and laid down the above rule.

(c) Seventy five Sekhiya rules of polite behaviour

These seventy five rules laid down originally for the proper behaviour of bhikkhus also apply to novices who seek admission to the Order. Most of these rules were all laid down at Savatthi on account of indisciplined behaviour on the part of a group of six bhikkhus. The rules can be divided into four groups. The first group of twenty six rules is concerned with good conduct and behaviour when going into towns and villages. The second group of thirty rules deals with polite manners when accepting alms-food and when eating meals. The third group of sixteen rules contains rules which prohibit teaching of the Dhamma to disrespectful people. The fourth group of three rules relates to unbecoming ways of answering the calls of nature and of spitting.

(d) Seven ways of settling disputes, Adhikaranasamatha

Pacittiya Pali concludes the disciplinary rules for bhikkhus with a Chapter on seven ways of settling cases, Adhikaranasamatha.

Four kinds of cases are listed:

- (i) Vivadadhikarana — Disputes as to what is dhamma, what is not dhamma; what is Vinaya, what is not Vinaya; what the Buddha said, what the Buddha did not say; and what constitutes an offence, what is not an offence.

- (ii) Anuvadadhikarana — Accusations and disputes arising out of them concerning the virtue, practice, views and way of living of a bhikkhu.

- (iii) Apattadhikarana — Infringement of any disciplinary rule.

- (iv) Kiccadhikarana — Formal meeting or decisions made by the Samgha.

For settlement of such disputes that may arise from time to time amongst the Order, precise and detailed methods are prescribed under seven heads:

- (i) Sammukha Vinaya: before coming to a decision, conducting an enquiry in the presence of both parties in accordance with the rules of Vinaya.

- (ii) Sati Vinaya: making a declaration by the Samgha of the innocence of an Arahat against whom some allegations have been made, after asking him if he remembers having committed the offence.

- (vi) Tassapapiyasika Kamma: making a declaration by the Samgha when the accused proves to be unreliable, making admissions only to retract them, evading questions and telling lies.

- (vii) Tinavattharaka Kamma the act of covering up with grass' — exonerating all offences except the offences of Parajika, Samghdisesa and those in connection with laymen and laywomen, when the disputing parties are made to reconcile by the Samgha.

(e) Rules of Discipline for the bhikkhunis

The concluding chapters in the Pacittiya Pali are devoted to the rules of Discipline for the bhikkhunis. The list of rules for bhikkhunis runs longer than that for the bhikkhus. The bhikkhuni rules were drawn up on exactly the same lines as those for the bhikkhus, with the exception of the two Aniyata rules which are not laid down for the bhikkhuni Order:

| Bhikkhu | Bhikkhuni | |

| (1) Parajika | 4 | 8 |

| (2) Samghadisesa | 13 | 17 |

| (3) Aniyata | 2 | - |

| (4) Nissaggiya Pacittiya | 30 | 30 |

| (5) Suddha Pacittiya | 92 | 166 |

| (6) Patidesaniya | 4 | 8 |

| (7) Sekhiya | 75 | 75 |

| (8) Adhikaranasamatha | 7 | 7 |

| Total: | 227 | 311 |

These eight categories of disciplinary rules for bhikkhus and bhikkhunis of the Order are treated in detail in the first two books of the Vinaya Pitaka. For each rule an historical account is given as to how it comes to be laid down, followed by an exhortation of the Buddha ending with "This offence does not lead to rousing of faith in those who are not convinced of the Teaching, nor to increase of faith in those who are convinced." After the exhortation comes the particular rule laid down by the Buddha followed by word for word commentary on the rule.

3. Mahavagga Pali

The next two books, namely, Mahavagga Pali which is Book III and Culavagga Pali which is Book IV Of the Vinaya Pitaka, deal with all those matters relating to the Samgha which have not been dealt with in the first two books.

Mahavagga Pali, made up of ten sections known as Khandhakas, opens with an historical account of how the Buddha attained Supreme Enlightenment at the foot of the Bodhi tree, how he discovered the famous law of Dependent Origination, how he gave his first sermon to the Group of Five Bhikkhus on the discovery of the Four Noble Truths, namely, the great Discourse on The Turning of the Wheel of Dhamma, Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta This was followed by another great discourse, the Anattalakkhana Sutta. These two suttas may be described as the Compendium of the Teaching of the Buddha.

The first section continues to describe how young men of good families like Yasa sought refuge in him as a Buddha and embraced his Teaching; how the Buddha embarked upon the unique mission of spreading the Dhamma 'for the welfare and happiness of the many' when he had collected round him sixty disciples who were well established in the Dhamma and had become Arahats; how he began to establish the Order of the Samgha to serve as a living example of the Truth he preached; and how his famous disciples like Sariputta, Moggallana, Maha Kassapa, Ananda, Upali, Angulimala became members of the Order. The same section then deals with the rules for formal admission to the Order, (Upasampada), giving precise conditions to be fulfilled before any person can gain admission to the Order and the procedure to be followed for each admission.

Mahavagga further deals with procedures for an Uposatha meeting, the assembly of the Samgha on every full moon day and on the fourteenth or fifteenth waning day of the lunar month when Patimokkha, a summary of the Vinaya rules, is recited. Then there are rules to be observed for rains retreat (vassa) during the rainy season as well as those for the formal ceremony of pavarana concluding the rains retreat, in which a bhikkhu invites criticism from his brethren in respect of what has been seen, heard or suspected about his conduct.

There are also rules concerning sick bhikkhus, the use of leather for footwear and furniture, materials for robes, and those concerning medicine and food. A separate section deals with the ceremonies where annual making and offering of robes take place.

4. Culavagga Pali

Culavagga Pali which is Book IV of the Vinaya Pitaka continues to deal with more rules and procedures for institutional acts or functions known as Samghakamma. The twelve sections in this book deal with rules for offences such as Samghadisesa that come before the Samgha; rules for observance of penances such as parivasa and manatta and rules for reinstatement of a bhikkhu. There are also miscellaneous rules concerning bathing, dress, dwellings and furniture and, those dealing with treatment of visiting bhikkhus, and duties of tutors and novices. Some of the important enactments are concerned with Tajjaniya Kamma, formal act of censure by the Samgha taken against those bhikkhus who cause strife, quarrels, disputes, who associate familiarly with lay people and who speak in dispraise of the Buddha, the Dhamma and the Samgha; Ukkhepaniya Kamma, formal act of suspension to be taken against those who having committed an offence do not want to admit it; and Pakasaniya Kamma taken against Devadatta announcing publicly that "Whatever Devadatta does by deed or word, should be seen as Devadatta's own and has nothing to do with the Buddha, the Dhamma and the Samgha." The account of this action is followed by the story of Devadatta's three attempts on the life of the Buddha and the schism caused by Devadatta among the Samgha.

There is, in section ten, the story of how Mahapajapati, the Buddha's foster mother, requested admission into the Order, how the Buddha refused permission at first, and how he finally acceded to the request be cause of Ananda's entreaties on her behalf.

The last two sections describe two important events of historical interest, namely, the holding of the first Synod at Rajagaha and of the second Synod at Vesali.

5. Parivara Pali

Parivara Pali which is Book V and the last book of the Vinaya Pitaka serves as a kind of manual. It is compiled in the form of a catechism, enabling the reader to make an analytical survey of the Vinaya Pitaka. All the rules, official acts, and other matters of the Vinaya are classified under separate categories according to subjects dealt with.

Parivara explains how rules of the Order are drawn up to regulate the conduct of the bhikkhus as well as the administrative affairs of the Order. Precise procedures are prescribed for settling of disputes and handling matters of jurisprudence, for formation of Samgha courts and appointment of well-qualified Samgha judges. It lays down how Samgha Vinicchaya Committee, the Samgha court, is to be constituted with a body of learned Vinayadharas, experts in Vinaya rules, to hear and decide all kinds of monastic disputes.

The Parivara Pali provides general principles and guidance in the spirit of which all the Samgha Vinicchaya proceedings are to be conducted for settlement of monastic disputes.