Nirvana

Nirvāṇa (Sanskrit: निर्वाण; Pali: निब्बान Nibbāna ; Prakrit: णिव्वाण) is an ancient Sanskrit term used in Indian religions to describe the profound peace of mind that is acquired with moksha (liberation). In shramanic thought, it is the state of being free from Suffering. In Hindu philosophy, it is union with the Brahman (Supreme Being).

Nirvana is a Sanskrit word which is originally translated as "perfect stillness". It has many other meanings, such as liberation, eternal bliss, tranquil extinction, extinction of individual existence, unconditioned, no rebirth, calm joy, etc. It is usually described as transmigration to "extinction", but the meaning given to "extinction" varies.

There are four kinds of Nirvana:

Nirvana of pure, clear self-nature; (Nirvana of pure, self-nature)

Nirvana with residue

Nirvana without residue

Nirvana of no dwelling

The word literally means "blown out" (as in a candle) and refers, in the Buddhist context, to the imperturbable stillness of mind after the fires of desire, aversion, and delusion have been finally extinguished. </poem>

Etymology

Phonetics

Nirvāṇa is a composed of three phones ni and va and na:

- ni (nir, nis, nih): out, away from, without, a term that is used to negate

- na: nor, never, do not, did not, should notVana is forest in/of the forest/forests; composed of flowers and other items of the forest., but vana has both phones van and va.

Van has both an auspicious and ominous aspect:

- va: weave

[[Abhidhamma]

The Abhidharma-mahāvibhāsa-sāstra, a sarvastivādin commentary, 3rd century BCE and later, describes the possible etymological interpretations of the word nirvana.

| Vana | +Nir | Nature of nirvana |

|---|---|---|

| The path of Rebirth | Leaving off | Being away from the path of Rebirth permanently avoiding all paths of transmigration. |

| Forest | Without | To be in a state which has got rid of, for ever, of the dense forest of the three fires of lust, malice and delusion |

| Weaving | Being free | Freedom from the knot of the vexations of karmas and in which the texture of both birth and death is not to be woven |

| Stench or stink | Without | Being without and free from all stench of karmas |

Each of the five aggregates is called a Skandha, which means "tree trunk".

Each Skandha informs the study of one's every normal experience, but eventually leads away from nirvana.

Skandha also means "heap" or "pile" or "mass", like an Endless knot's path, or a forest.

Overview

Nirvāṇa is the soteriological goal within the Indian religions, Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism.

It is synonymous with the concept of liberation (moksha) which refers to release from a state of Suffering after an often lengthy period of committed spiritual practice. The concept of Nirvāṇa comes from the Yogic traditions of the Sramanas whose origins go back to at least the earliest centuries of the first millennium BCE.

The Pali Canon contains the earliest written detailed discussion of Nirvāṇa and the concept has thus become most associated with the teaching of the historical Buddha.

It was later adopted in the Bhagavad Gita of the Mahabharata. In general terms Nirvāṇa is a state of transcendence (Pali: lokuttara) involving the subjective experience of release from a prior state of bondage.

This is the result of a natural re-ordering of the mind and body via means of yogic discipline or sadhana. According to the particular tradition, with the experience of Nirvāṇa the mind (Buddhism) or soul (Jainism) or

spirit (Hinduism) has ended its identity with material phenomena and experiences a sense of great peace and a unique form of awareness or intelligence that is called Bodhi in Buddhism, Kevala Jnana in Jainism, kaivalya (Asamprajnata Samadhi) in Yoga.

It has several other names as well. Hinduism uses the terms Aikantya, Apamarga, Brahma-upalabdhi, Sahaj, Sakshatkara, Sayujya, Videhalcivalyam and Yogakshemma, while Buddhism also uses the term Bodhi. Because nirvana represents an

advanced form of Samadhi or Jhana Hinduism acknowledges it as Nirvikalpa Samadhi, Buddhism, as Ceto-vimutti Samadhi and Jainism as Asamprajyat Samadhi. Mukti is sometimes elaborated on as Atyantiki Mukti, Samipya Mukti (or Salokja Mukti), and Sadrisya Mukti.

Buddhism

=Sutta Pitaka =

In the Sutta Pitaka The Buddha describes Nirvāṇa as the perfect peace of mind possessed by one who is liberated (Pali: Arahant).

It is to be distinguished from peaceful moods arising from a temporary absence of anger, sensual desire, anxiety and other afflicting states (Kleshas).

Nirvāṇa is an 'ultimate' peace that is achieved after a lengthy process of mind-body transformation during which the uprooting and final dissolution of the volitional formations (Pali: samskaras or sankharas) (structures within the unconscious mind that form the underlying basis for psychological dispositions) takes place.

According to The Buddha, during the course of many repeated incarnations these deeply buried structures (also referred to as karmic 'seeds'; Sanskrit: Bija) are either strengthened by indulgence in worldly activities (a person doing so is described as a Puthujjana) or weakened by following the path of the Enlightened Ones.

The sankharas are the ultimate cause for the material incarnation of Sentient beings. In the Dhammapada,

The Buddha says of Nirvāṇa that it is "the highest happiness", an enduring happiness qualitatively different from the limited, transitory happiness derived from impermanent things.

The Buddha explains the unique character of Nibbāna as being due to the mind having become unconditioned (asankhata) which is to say free from the conditions formerly obscuring it by the volitional formations.

This ultimate state is described by The Buddha as "deathlessness" (Pali: amata or amāravati) and naturally accrues in the fullness of time to one having lived a life committed to the threefold training (Noble Eightfold Path).

Such a life is concerned with performing wholesome actions (Pali: kusala Kamma) with positive results and finally allows the cessation of the origination of worldly activities altogether with the attainment of Nibbāna.

The Buddha's teachings in the Pāli Canon present Nirvāṇa as a radical reordering of consciousness. This reordering is made possible through the cultivation of special states of absorbed concentration called jhānas.

These are states of deep relaxation in which a high degree of mental alertness and concentration is present. The jhanas in turn are made possible by a training in the establishing of Mindfulness.

In Theravada whose concept of the Bodhisattva difffers from that of the Mahayana the Arahant abiding in Nirvāṇa is "the ideal personality, the true human being".

The Nirvāṇa of the Sutta pitaka is never conceived of as a place (such as one might conceive heaven), but rather the antinomy of samsāra (see below) which itself is synonymous with ignorance (avidyā, Pāli avijjā).

This said:: "'the liberated mind (Citta) that no longer clings' means Nibbāna" (Majjhima Nikaya 2-Att. 4.68).This state of being is described as transcendent or supramundane (Pali: lokuttara). Nirvāna is meant specifically—as pertains gnosis—that which ends the identity of the mind (Citta) with empirical phenomena.

Doctrinally, Nibbāna is said of the mind which "no longer is coming (Bhava) and going (vibhava)" but which has attained a status in perpetuity, whereby "liberation (vimutta) can be said."It carries further

connotations of stilling, cooling, and peace. The realizing of Nirvāṇa is compared to the ending of avidyā (ignorance) which perpetuates the will (Pali: cetana) into effecting the incarnation of mind into

biological form passing on forever through life after life (samsāra). Samsāra is caused principally by craving and ignorance (see Dependent origination). A person can attain nirvāna without dying.

When a person who has realized Nirvāṇa dies, his death is referred as parinirvāṇa (Pali: parinibbana), his fully passing away, as his life was his last link to the cycle of death and Rebirth (samsāra), and he will not be

reborn again. Buddhism holds that the ultimate goal and end of samsāric existence (of ever "becoming" and "dying" and never truly being) is realization of nirvāna. What happens to a person after his parinirvāṇa cannot be

explained, as it is outside of all conceivable experience. Through a series of questions, Sariputta brings a Monk to admit that he cannot pin down the Tathagata as a truth or reality even in the present life, so to speculate regarding the ontological status of an Arahant after death is not proper.

See Tathagata#Inscrutable.

Karma and Rebirth

- See also:Rebirth

Until final liberation (called moksha in Indian religions) beings wander through samsāra, the impermanent and Suffering-generating realms of desire, form, and formlessness. Samsāra is perpetuated by craving and

ignorance.By uprooting the volitional dispositions one is no longer subject to further Rebirth in samsāra . A liberated person performs neutral actions (Pali: kiriya Kamma) producing no fruit (Vipaka), but

nonetheless preserves a particular individual personality. This is the result of the traces of his or her karmic heritage.

Bodhi and the Path to Liberation

- See also:Bodhi, Noble Eightfold Path and Buddhist Paths to liberation

Nirvana is achieved after a long process of committed application to the path of purification (Pali: Vissudhimagga) taught by The Buddha.

The Buddha explained that the disciplined way of life he recommended to his students (Dhamma-Vinaya) is a Gradual training extending often over a number of years.

To be committed to this path already requires that a seed of Wisdom is present in the individual.

This Wisdom becomes manifest in the experience of awakening (Bodhi). Attaining Nibbāna, in either the current or some future birth, depends on effort, and is not pre-determined. Nirvana is the result of following the Noble Eightfold Path.

Parinirvana

A person can attain nirvāna without dying. When a person who has realized Nirvāṇa dies, his death is referred as parinirvāṇa (Pali: parinibbana), his fully passing away, as his life was his last link to the cycle of

death and Rebirth (samsāra), and he will not be reborn again. What happens to a person after his parinirvāṇa cannot be known, as it is outside of all conceivable experience.Through a series of questions, Sariputta brings a Monk to admit

that he cannot pin down the Tathagata as a truth or reality even in the present life, so to speculate regarding the ontological status of an Arahant after death is not proper. See Tathagata#Inscrutable.

Theravada

Visuddhimagga

The path of purification

In the Visuddhimagga, Ch. I, v. 6 (Buddhaghosa & Ñāṇamoli, 1999, pp. 6–7), Buddhaghosa identifies various options within the Pali canon for pursuing a path to nirvana, including:

- By Jhana and understanding (see Dh. 372)

- by deeds, vision and righteousness (see MN iii.262)

- By virtue, consciousness and understanding (7SN i.13);

- by virtue, understanding, concentration and effort;

- By the four foundations of mindfulness.Depending on one's analysis, each of these options could be seen as a reframing of the Buddha's Threefold Training of virtue, mental development and wisdom.

Levels of attainment

- See also:Four stages of enlightenment

Individuals up to the level of non-returning may experience nirvāna as an object of mental consciousness. Certain contemplations with nibbana as an object of samādhi lead, if developed, to the level of [[non-

returning]]. At that point of contemplation, which is reached through a progression of insight, if the meditator realizes that even that state is constructed and therefore impermanent, the fetters are destroyed, arahantship is attained, and nibbāna is realized.

Luminous mind

- See also:Luminous mind

In many places The Buddha describes his Enlightenment in terms of "knowing". In the Dhammacakkapavattana Sutta, "Knowing arose" (ñāṇa udapādi). With Nirvāṇa the consciousness is released, and the mind becomes aware in a

way that is totally unconstrained by anything in the conditioned world. The Buddha describes this in a variety of passages.

One way is as "Consciousness without feature, without end, luminous all around."In one interpretation, the "luminous consciousness" is identical with Nirvāṇa. Others disagree, finding it to be not Nirvāṇa itself, but instead to be a kind of consciousness accessible only to Arahants. A passage in the Majjhima Nikaya likens it to empty space.

Awareness

Ajahns Pasanno and Amaro, contemporary vipassana-teachers write that what is referred to with the use of the word "viññana" is the quality of awareness, and that the use of the term "viññana" must be in a broader way than it usually is

meant:: The Buddha avoided the nit-picking pedantry of many philosophers contemporary with him and opted for a more broad-brush, colloquial style, geared to particular listeners in a language which they could understand. Thus ‘viññana’ here can

be assumed to mean ‘knowing’ but not the partial, fragmented, discriminative (vi-) knowing (-ñana) which the word usually implies. Instead it must mean a knowing of a primordial, transcendent nature, otherwise the passage which contains it would be self-contradictory."

They then give further context for why this choice of words may have been made; the passages may represent an example of The Buddha using his "skill in means" to teach Brahmins in terms they were familiar with.This "non-manifestive consciousness" differs

from the kinds of consciousness associated to the six sense media, which have a "surface" that they fall upon and arise in response to. According to Peter Harvey, the early texts are ambivalent as to whether or not the term "consciousness" is

accurate. In a liberated individual, this is directly experienced, in a way that is free from any dependence on conditions at all.

Unmediated knowledge

For liberated ones the luminous, unsupported consciousness associated with Nibbana is directly known without mediation of the mental consciousness factor in dependent co-arising, and is the transcending of all objects of

mental consciousness. It differs radically from the concept in the pre-Buddhist Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita of Self-realization, described as accessing the individual's inmost consciousness, in that it is not

considered an aspect, even the deepest aspect, of the individual's personality, and is not to be confused in any way with a "

Self". Furthermore, it transcends the sphere of infinite consciousness, the sixth of the Buddhist jhanas, which is in itself not the ending of the conceit of "I".

Nagarjuna alluded to a passage regarding this level of consciousness in the Dighanikaya in two different works. He wrote that

- The Sage has declared that earth, water, fire, and wind, long, short, fine and coarse, good, and so on are extinguished in consciousness ... Here long and short, fine and coarse, good and bad, here name and form all stop.

A related idea, which finds support in the Pali Canon and the contemporary Theravada practice tradition despite its absence in the Theravada commentaries and Abhidhamma, is that the mind of the Arahant is itself Nibbana.

Mahayana

Nirvana also plays a role in Mahayana Buddhism, but is not regarded to be the final goal, nor to be different form Samsara. The Tathagatagarbha-literature gives a positive interpretation of Nirvana.

Bodhisattva-path

- See also:Bodhisattva and Bhūmi

A Bodhisattva must achieve full liberation as part of the process of achieving Buddhahood as defined by the Mahayana. On the Bodhisattva-paths, the 8th Bhumi or 8th ground is equivalent to the attainment of Hinayana Arhatship or Hinayana Buddhahood.

Levels of attainment

Pabongka Rinpoche compares the path to full Buddhahood to climbing a mountain, which has:

- A base-camp located at the level of ethical conduct for practitioners of the small scope (non-Buddhists and non-practicing Buddhists),

- A base-camp at individual liberation for practitioners of the medium scope (Theravada),

- A last and most difficult climb peak of the mountain for practitioners of the great scope (Mahayana).

Omniscience

According to Pabongka Rinpoche, the Theravadan's argue that the base camp of liberation, located above the clouds of Suffering and Rebirth, is the peak of the mountain. The Mahayanist's, however, insist that even though the obstructions to liberation have been removed, the obstructions to full omniscience have not been removed.

The end stage practice of the Mahayana removes the imprints of delusions, the obstructions to omniscience, which prevent simultaneous and direct knowledge of all phenomena. Only Buddhas have overcome these obstructions, according to Mahayana Buddhism, and, therefore, only Buddhas have omniscience knowledge.

Samsara is Nirvana

- See also: Two-truths doctrine

In Mahāyāna Buddhism, nirvana and Samsara are said to be not different when viewed from the ultimate nature of the Dharmakaya. An individual can attain nirvana by following the Buddhist path.

If they were ultimately different this would be impossible. Thus, the duality between nirvana and Samsara is only accurate on the conventional level. Another way to arrive at this conclusion is through the analysis that all

phenomena are empty of an essential identity, and therefore Suffering is never inherent in any situation. Thus liberation from Suffering and its causes is not a metaphysical shift of any kind.

Both the Theravāda and Mahāyāna schools makes the antithesis of Samsara and Nibbāna the starting point of the quest for deliverance. The Mahāyāna schools treat this polarity as a preparatory lesson tailored for those with blunt

faculties, to be eventually superseded by some higher realization of non-duality. The Theravāda school, however, treats this antithesis as determinative of the final goal: the transcendence of Samsara and the attainment

of liberation in Nibbāna. From the standpoint of the Pāli Suttas, even for The Buddha and the Arahants Suffering and its cessation, Samsara and Nibbāna, remain distinct.

Both schools agree that Shakyamuni Buddha appeared in Saṃsāra while having attained Nirvāṇa, in so far as he was seen by Suffering beings, while himself being free of the cycle of Suffering.

Tathagatagarba and Buddha-nature

- See also:Buddha-nature

Purified mind

- See also:Dharmakaya

In some Mahayana/Tantric texts nirvana is described as purified, non-dualistic 'superior mind'. The Samputa, for instance, states:

- Undefiled by lust and emotional impurities, unclouded by any dualistic perceptions, this superior mind is indeed the supreme nirvana.'

Some Mahayana traditions see The Buddha in almost docetic terms, viewing his visible manifestations as projections from within the state of nirvana. According to Professor Etienne Lamotte, Buddhas are

always and at all times in nirvana, and their corporeal displays of themselves and their Buddhic careers are ultimately illusory. Lamotte writes of the Buddhas:

- They are born, reach Enlightenment, set turning the Wheel of Dharma, and enter nirvana. However, all this is only illusion: the appearance of a Buddha is the absence of arising, duration and destruction; their nirvana is the fact that they are always and at all times in nirvana.’

Mahaparinirvana-Sutra

Mahayana Mahaparinirvana Sutra

Some Mahayana sutras go further and attempt to characterize the nature of nirvana itself. The Mahayana Mahaparinirvana Sutra, which has as one of its main topics precisely the realm or dhatu of nirvana, has The Buddha speak of four

essential elements which make up nirvana. One of these is ‘Self’ (Atman), which is construed as the enduring Self of The Buddha. Writing on this Mahayana understanding of nirvana, William Edward Soothill and Lewis Hodous state:

- ‘The Nirvana Sutra claims for nirvana the ancient ideas of permanence, bliss, personality, purity in the transcendental realm. Mahayana declares that Hinayana, by denying personality in

the transcendental realm, denies the existence of The Buddha. In Mahayana, final nirvana is both mundane and transcendental, and is also used as a term for the Absolute.

At the time this scripture was written, there was already a long tradition of positive language about nirvana and The Buddha. While in early Buddhist thought nirvana is characterized by permanence, bliss, and purity,

it is viewed as being the stopping of the breeding-ground for the "I am" attitude, and is beyond all possibility of the Self-delusion.

The Mahaparinirvana Sutra, a long and highly composite Mahayana scripture, refers to The Buddha's using the term "Self" in order to win over non-Buddhist ascetics.

The Ratnagotravibhaga, a related text, points out that the teaching of the Tathagatagarbha is intended to win Sentient beings over to abandoning "affection for one's self" - one of the five defects caused by non-Buddhist teaching. Youru Wang notes similar language in The Lankavatara Sutra, then writes:

- Noticing this context is important. It will help us to avoid jumping to the conclusion that Tathagatagarbha thought is simply another case of metaphysical imagination."

Kosho Yamamoto, translator of the full-length Nirvana Sutra, expresses the view that the non-Self teaching is expedient only and that in the Nirvana Sutra a hidden teaching on the True Self is disclosed by The Buddha:

- He [the Buddha says that the non-Self which he once taught is none but of expediency ... He says that he is now ready to speak about the undisclosed teachings. Men abide in upside-down thoughts. So he will now speak of the affirmative attributes of nirvana, which are none other than the Eternal, Bliss, the Self and the Pure.

In consonance with this, researcher on the Nirvana Sutra, Dr. Tony Page, comments:

- On the specific question of the supramundane or nirvanic Self, it is apparent that the Nirvana Sutra does assert an eternally abiding entity or Dharma – what we might call the “Buddha-Self”, since The Buddha utters the equation ‘Self = Buddha’ - as an ever-enduring reality of the highest order. That Buddha-Self is one with Nirvana.

Positive language

According to some scholars, the language used in the Tathāgatagarbha genre of sutras can be seen as an attempt to state orthodox Buddhist teachings of Dependent origination using positive language instead. Yamamoto points

out that this ‘affirmative’ characterization of nirvana pertains to a supposedly higher form of nirvana—that of ‘Great Nirvana’. Speaking of the 'Bodhisattva Highly Virtuous King' chapter of the Nirvana Sutra, Yamamoto quotes the scripture itself:

- What is nirvana? ...this is as in the case in which one who has hunger has peace and bliss as he has taken a little food.

Yamamoto continues with the quotation, adding his own comment:

- But such a nirvāna cannot be called “Great Nirvāna”". And it [i.e. the Buddha’s new revelation regarding nirvana goes on to dwell on the “Great Self”, “Great Bliss”, and “Great Purity”, all of which, along with the Eternal, constitute the four attributes of Great Nirvana.

Quotations

- "Where there is nothing; where naught is grasped, there is the Isle of No-Beyond. Nirvāṇa do I call it—the utter extinction of aging and dying."

- "There is that dimension where there is neither earth, nor water, nor fire, nor wind; neither dimension of the infinitude of space, nor dimension of the infinitude of consciousness, nor dimension of nothingness, nor

dimension of neither perception nor non-perception; neither this world, nor the next world, nor sun, nor moon. And there, I say, there is neither coming, nor going, nor stasis; neither passing away nor arising: without stance, without foundation, without support mental object. This, just this, is the end of stress." Udana VIII.1

Jainism

In Jainism, nirvana means final release from the karmic bondage. When an enlightened human, such as an arihant or a Tirthankara, extinguishes his remaining aghatiya karmas and thus ends his worldly existence, it is

called Nirvāṇa. Moksha (liberation) follows Nirvāṇa. An Arhat becomes a siddha ("one who is accomplished") after Nirvāṇa.

Mahavira’s Nirvāṇa

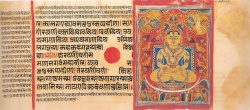

Jains celebrate Diwali as the day of Nirvāṇa of Mahavira. Kalpasutra gives an elaborate account of Mahavira’s Nirvāṇa.

- The aghatiya Karma’s of Venerable Ascetic Mahavira got exhausted, when in this Avasarpini era the greater part of the Duhshamasushama period had elapsed and only three years and eight and a half months were left. Mahavira had

recited the fifty-five lectures which detail the results of Karma, and the thirty-six unasked questions (the Uttaradhyana Sutra). The moon was in conjunction with the asterism Svati, at the time of early morning, in the town of Papa,

and in king Hastipala's office of the writers, (Mahivir) single and alone, sitting in the Samparyahka posture, left his body and attained Nirvāṇa, freed from all pains.” (147)

- In the fourth month of that rainy season, in the seventh fortnight, in the dark (fortnight) of Karttika, on its fifteenth day, in the last night, in the town of Papa, in king Hastipala's office of the writers, the Venerable Ascetic

Mahavira died, went off, cut asunder the ties of birth, old age, and death; became a Siddha, a Buddha, a Mukta, a maker of the end (to all misery), finally liberated, freed from all pains. (123)

- That night in which the Venerable Ascetic Mahavira died, freed from all pains, was lighted up by many descending and ascending gods. (125)

- In that night in which the Venerable Ascetic Mahavira, died, freed from all pains, the eighteen confederate kings of Kasi and Kosala, the nine Mallakis and nine Licchavis, on the day of new moon, instituted an illuminations

on the Poshadha, which was a fasting day; for they said: 'Since the light of intelligence is gone, let us make an illumination of material matter!' (128)

As moksha

Uttaradhyana Sutra provides an account of Gautama explaining the meaning of Nirvāṇa to Kesi, a disciple of Parshva.

- There is a safe place in view of all, but difficult of approach, where there is no old age nor death, no pain nor disease. It is what is called Nirvāṇa, or freedom from pain, or perfection, which is in view of all; it is the

safe, happy, and quiet place which the great sages reach. That is the eternal place, in view of all, but difficult of approach. Those sages who reach it are free from sorrows, they have put an end to the stream of existence. (81-4)

Hinduism

In Hinduism, moksha is the liberation from the cycle of birth and death and one's worldly conception of self. A person reaches moksha as nirvana is attained. Moksha is derived from the sanskrit word Muktha

literally meaning one who is free from bondage, is free. But it is found that according to some Indian Hindu philosophers the last bondage is the passion for liberation itself which must be renounced before the soul can be perfectly free, and the

last knowledge is the realisation that there is none bound, none desirous of freedom, but the soul is for ever and perfectly free, that bondage is an illusion and the liberation from bondage is an illusion too. Not only are that every one

are bound but in play, the situation is compared as mimic knots which have such a nature that itself can at its pleasure undo them.

Bhagavad Gita

In Bhagavad Gita, Krishna explains that Brahma nirvana (nirvana in Brahman) can be attained by one who is capable of cognizing the essence of Brahman; by getting rid of vices, becoming free from

duality, free from the worldly attractions and anger, dedicated to spiritual pursuits, having subdued thoughts and cognized Atman, and dedicating oneself to the good of all.

Brahma nirvana is the state of release or liberation; the union with the divine ground of existence (Brahman) and this experience of blissful ego-lessness.

In the words of Mahatma Gandhi: "The nirvana of the Buddhists is Shunyata, emptiness, but the nirvana of the Gita means peace and that is why it is described as brahma-nirvana oneness with Brahman."

Falun Gong (Falun Dafa)

In Falun Gong, the characteristic of the universe is described in three words: Truthfulness-Compassion-Forbearance. During one's cultivation process, a Falun Gong practitioner continuously improve his/her xinxing (mind nature) level by assimilating to this characteristic. A practitioner's Enlightenment can occur gradually or suddenly, depending upon one's inborn

quality (genji). The level of cultivation is indicated by the height of gong (energy) level. In the book 'The Great Consummation Way of Falun Dafa', Mr. Li Hongzhi mentioned, "Falun Buddha Fa aims directly at people’s hearts and

makes it clear that cultivation of xinxing is the key to increasing gong. A person’s gong level is as high as his or her xinxing level, and this is an absolute truth of the universe. “Xinxing” includes the transformation of virtue

(de) (a white substance) and Karma (a black substance), the abandonment of ordinary human desires and attachments, and the ability to endure the toughest hardships of all. It also encompasses many types of things that a

person must cultivate to raise his or her level." When one achieves Consummation at the end of cultivation, the practitioner will have become an enlightened being. Eight-tenth of the gong level will substantiate the enlightened being's heavenly paradise.

Brahma Kumaris

In Brahma Kumaris religion, nirvana is called paramdham (supreme abode) or shantidham (abode of peace) and is highest of three world, original home of the soul and Supreme Soul Shiva.

Source

Nirvana (Skt. nirvāṇa; Tib. མྱ་ངན་ལས་འདས་པ་, nya ngen lé dé pa; wyl. mya ngan las 'das pa) - literally ‘extinguished’ in Sanskrit and ‘beyond suffering’ in Tibetan; enlightenment itself. It is the state of peace that results from cessation, the total pacification of all suffering and its causes.

Subdivisions

As a blanket term, 'nirvana' indicates the various levels of enlightenment attainable in both the Shravakayana, Pratyekabuddha yana and Mahayana, namely, the enlightenment of the shravakas, pratyekabuddhas, and buddhas. It

should be noted, however, that when nirvana, or enlightenment, is understood simply as emancipation from samsara (the goal, in other words, of the Hinayana), it is not understood as buddhahood.

As expounded in the Mahayana, buddhahood utterly transcends both the suffering of samsara and the peace of nirvana. Buddhahood is therefore referred to as ‘non-abiding nirvana’, in other words, a state that abides neither in

the extreme of samsara nor in that of peace.[1]

Patrul Rinpoche, in his commentary on the Abhisamayalankara, explains that the texts of the Madhyamika tradition mention four types of nirvana:

- non-abiding nirvana, which is the great nirvana beyond both ordinary samsaric existence and the lesser nirvana of the basic vehicle.

- nirvana with remainder, which is the realization attained by the arhats of the basic vehicle who have not yet relinquished their psycho-physical aggregates.

- nirvana without remainder, the consummate realization of the arhats of the basic vehicle, who have passed into a state of cessation, leaving their pscycho-physical aggregates behind.

Footnotes

- ↑ From the glossary in the Treasury of Precious Qualities translated by Padmakara Translation Group.