Feeding the Monks

The Traditional Alms Round. The alms round was, for the Buddha, a key feature of the monastic life and the alms bowl is, for all Buddhists, a symbol of the monastic order. The Pali word for alms round is pindapata, which colorfully means “dropping a lump,” describing the process whereby food accumulates in the alms bowl. The tradition is that

monks or nuns leave the monastery, or wherever they are dwelling (most ideally, the root of a tree or a cemetery), either singly or in a group. As a group they walk single-file according to seniority, that is, ordination date. The robes are arranged formally, covering both shoulders. The monks walk barefooted into a village and then from house to house, not favoring rich or

poor neighborhoods, accepting, but not requesting, what is freely donated, that is, dropped into one’s bowl. Everything dropped into the bowl, according to ancient tradition, is simply mixed together, since monks are asked not to favor one food over another, and by extension should not favor one blend of foods over another, just as their stomach’s will not a few seconds later.

Carrying the ancient tradition into the modern context can result in some rather unique blends, for instance, curry and cake, shrimp and mangoes. Monastics are instructed not to endear themselves to the lay with the intention of improving their intake during alms rounds, not to ask for anything directly except in an emergency, not to express thanks for donations received, and to receive without establishing eye contact. This ritualized behavior can be seen every day in virtually any village or city in Burma.

here are a lot of rules for monks around eating. Foods must be offered by hand from a layperson, though monks who have received food can share, or trade, offerings with other monks. Most foods must be consumed by noon the day they are offered, so cannot be saved for a snack or for the next day’s meal, except to return them to a layperson. Filtered fruit juices may be offered and consumed after noon, until dawn the next day. “Tonics” (sugar/molasses, honey, butter and a couple of other things) may be consumed any time and saved up to seven days after being offered. Medicines can be kept forever.

Some Variations. Almost universally the bowl in Theravada lands is larger than most appetites, since it also serves as a kind of suitcase for mendicant forest monks, and is often used to collect alms for more than one monk, for instance, if another monk is too sick to go on alms rounds. The bowl will also have a strap, which is slung over the right shoulder to

carry the weight of the bowl when walking, and a lid. The lid was added sometime after the Buddha; I can imagine two scenarios that might have motivated this originally, both involving birds. There seem to be many variations in alms paraphernalia that have to do with the issue of mixing foods.

For purists all of the offerings just go in the big bowl. The lid turned upside down allow a two-way separation: the bhikkhu can collect noodles, sauces, beans, cooked vegetables into the big bowl, but turn the lid upside down to form a tray to receive whatever might be difficult to imagine as part of the stew accumulating in the big bowl: mango slices, cookies, soap, razor blades, candles (some non-food items are also occasionally offered). One custom in Burma is to carry little containers

within the main bowl to separate the different kinds of sauces, beans, cooked vegetables and such. The kind of interaction the monk has with lay folks can also vary. Some monks will simply pass silently from house to house, receive offerings silently and move on silently. Others will speak with the lay folks and invite questions concerning Dhamma or will simply make a habit of offering a short discourse at each house. Most lay people will make prostrations and often offer tea for immediate consumption to monks who linger a while.

Accepting Alms in Large Monastery. The traditional alms round, whereby monks walk from house to house, does not work so well for a large monastery, for instance, monastic universities, with many monks and no substantial village in the immediate vicinity. In such cases individual lay people will often come to the monastery to make large but occasional

offerings, and also local staff will prepare food on behalf of lay donors, at least cook the rice. But often the form of the alms round is retained. At Pa Auk Tawya in Burma there is a special building called Pindapata (Drop-a-Lump) Hall constructed with this in mind. The monk walks with his bowl and with his robes formally arranged through a gauntlet of people offering food. The first generally offers rice and the others various curries and vegetables which go into the same bowl, or fruits and other items that can be accepted into the inverted lid of the bowl.

Family-Style Eating. Many monasteries and homes at which food is made available at the place of consumption forgo the traditional form of the alms round in favor of offering food family-style at a table in dishes from which the monks can help themselves. Generally conventional plates and bowls and silverware or chopsticks are used for eating. This is a common

practice at academic monasteries, including those in the Sitagu system, and seems to be the norm in Myanmar when monks are invited into homes for meals. In Myanmar many monks still eat with their fingers rather than with Western eating implements.

Generally lay people will not sit at the table with monks but will begin their meal afterwards, eating what the hungry monks have left and supplementing it as necessary with other food that has been prepared. Sometimes the monastic and lay meals will overlap, but almost always at separate tables.

In family-style service it is important to offer the food items clearly lest a confused monk take what is not freely given. Since the food items may be shared by the monks, each item can be accepted by a single monk. That monk is implicitly assumed to be willing to share with all other monks. The clever Burmese will typically make things easy by offering a whole table of

food at once as if it were a giant dish. To do this generally requires at least two lay people to physically lift the whole table and at least one monk to receive the whole table by grabbing onto the edge. Because lay people are so eager to give, generally all of the lay people present will help lift the table. Only one monk has to touch the table for it to be considered offered, but generally all of them will accept the table because it is so much fun.

One interesting even more clever variant of the whole table offering that I have seen in Myanmar is use two tables, table A for the main course and table B for desserts, fruit and coffee or tea. When the monks sitting on the floor around table A are finished, some lay people will lift table A up over the heads of the monks and into the midst of waiting laypeople already configured around an imaginary table, then place table B where table A had been. Then the laypeople can begin the main course as the monks begin the second.

Receiving and Accepting Alms as Practice. The Buddha has a lot to say about alms rounds in the Vinaya, the Guide to monastic discipline,. It is not simply a way to feed the monks and nuns; it had a much greater role to play in realigning the values of both monastic and lay.

The alms round is an monastic obligation. Even when food was close at hand, the alms round was not to be disregarded. For instance, when the Buddha returned to visit his princely home after his alms-financed Enlightenment, he continued his alms rounds in the streets of Kapilavattu much to the distress of his aristocratic father. Of course he could

have been enjoying sumptuous meals with no expenditure of time and effort, but chose not to. Furthermore, the Buddha is known to have criticized one of his disciples, an arahat who could meditate for seven days at a stretch without food, for neglecting his daily alms rounds in favor of meditation. Moreover, the Buddha did not permit monastics to grow, cook or even store

food, but to eat only what was duly offered from a lay hand on a daily basis, locking them into strict dependence. Burmese monks, both in Myanmar and in America often make themselves available to receive offerings at great inconvenience, for instance being driven from Austin to Waco (an hour and a half each way) or Dallas (over three hours) to accept a lunch invitation.

Benefits for monks. The tradition of feeding monks puts monks in an absolute and vulnerable state of dependence on the laity. Why is this desirable? The development of humility is certainly a part of it; the lay folks have the key to the car and the nuns and monks don’t go anywhere without them. Accepting the generosity of the lay graciously, having no resources at all of one’s own, even one’s robes, that are not donated, puts the monastic in an uncommon frame of reference,

but also does the same for the lay donor. The receipt of offerings also sets the bar very high for monastic practice. The monk quickly realizes that the offerings and the respect bestowed upon monks does not result from an individual assessment of the particular monk’s qualities; they are given in a non-judgmental fashion. This means that it is the Sangha that is

the real recipient, the offerings are made out of respect for the present and historical monastic community. This leaves the assessment of the individual monastic up to the individual monastic, who must ask, “Am I upholding the reputation of the Sangha,” or “Am I myself worthy of this offering.” The respect is a container and the monk is obligated to fill it.

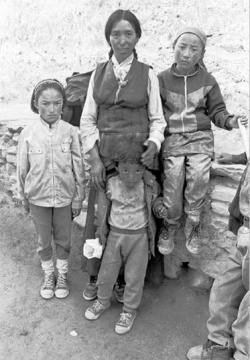

Naturally the alms round gives the monk a connection to the lives of the laity, so that their practice is not in a monastic bubble. In Myanmar I appreciated the opportunity to see how people live. People are generally poor by any

American standard. Houses are for the most part leaky shacks with plank walls, almost on top of each other, small alleys in between, electricity but no other amenities. But I don’t get the sense that most people think of themselves as poor or deprived; they live with a sense of dignity. And every act of generosity toward monks reminds them that they have wealth to share.

Benefits for the laity. Remarkably, every time the monastic accepts the lay donor receives a gift. This is paradoxical, but believe me, you see the sugar plums dancing in their eyes. The relationship is unlike what one finds in conventional human intercourse. This is the economy of gifts that provides the context of the most fundamental

Buddhist value and practice, those of dana. The benefits are greatest when donations are personalized, when they come through one’s own hands rather than through a delegate. For instance, a wealthy donor may choose to donate a meal to an entire

monastary. If possible he or she will be present for the meal, will make all the formal gestures of respect to the monastics and will help to serve, maybe additionally overseeing the process of serving. Special occasions are often marked by making a donation to a monastery or by inviting a group of monks to one’s home for a meal. These include both happy occasions, such as birthdays, reversing the direction of gift-giving more commonly recognized in the West, or such as times of grief, in which gift-giving seems to have a particularly therapeutic value.

What the layperson can offer monks is limited by what they can accept. Monks cannot accumulate many goods, they generally should not accept abundant robes or any money, nor any luxury items. Monks are also supposed to practice nondiscrimination of quality or fineness, of not being caught up in sensual pleasure. But food offers the laypeople a

kind of loophole through which they are free to arouse sensual desire in the monks, a loophole that is often exploited by those rascals through offering sumptuous and costly dishes to test the resolve of even the most well-intentioned monks. Laypeople then love to gather around and watch the monk or monks eat. To the monk it is a bit like feeding time at the zoo, on the other side of the bars.