Five Skandhas

Five Skandhas The five groups of elements (Dharmas) into which all existences are classified in early Buddhism.

The five are:

Rupa (matter),

Vedana (feeling),

Sanjna (ideation);

Samskara (forces or drives)

Vijnana (consciousness or sensation).

Group, heap, aggregate;

the five constituents of the personality;

form,

feeling,

perception,

impulses,

consciousness;

the five factors constituting the individual person.

The word we sometimes use in English interchangeably with "person" is "individual" that carries the idea of "not divisible." But the Sanskrit term pudgala that is used by Jains and by Buddhists which confers that same "person" meaning actually connotes a temporary entity that is prone to separation into parts and then, to assimilation. It is not one whole that is a solid, indivisible entity. Instead the person is viewed as made up of five different aspects called the 5 Skandhas or Five Aggregates. These are not physical components, but rather an agglomeration or coming together of subliminal inclinations or tendencies.

Suffering and the Skandhas

"Everything is suffering [Skt. dukkha" is the 1st 'Noble' Truth (aryasatya) Noble> arya which here means supreme, ultimate.)

Suffering = un-satisfactoriness, not OK, and much of that has to do with the impermanent nature of phenomena [things, events and states] due in part to the fact they are composed of temporary assemblages or skandhas.

Impermanence

Existence is suffering primarily because, by its very nature, it is impermanent. That is, people, animals, things, circumstances ("life-style") and all the components that go to make them up - good health - are transitory. Often the word chosen to translate dukkha is 'unsatisfactoriness'.

Though they say in French, The more things change, the more they remain the same] that sameness is never permanent but always changing, uncertain, often risky and creating of stress.

The doctrine of why and how this is appears in the Mahanidana Sutta or The Great Causation Sutra.

The Buddhist view is that every individual is an entity composed of five categories of phenomena or qualities that may be thought of as aggregates, skandhas in Sanskrit; sometimes translated as heaps or accumulations.

The Five Skandhas, also called Formations are:

- form (rupa)

- apperception or sensibility

- perception

- volition, will

- consciousness

1. Form is composed of matter made up of four elements: earth, water, fire, wind.

2. Apperception or sensibility is derived from the sense organs:

- eye enables sight

- ear enables sound

- nose enables odour

- tongue enables taste

- "body" enables touch

- mind enables the experiences of the five organs above, but also of its own objects called, like the word for the Teachings, dharmas ('facts').

This set of pairs, ie. organ + function, is known as the Twelve (12) Bases of Consciousness.

3. Perception is a product of the six externals above: sight, sound, etc. It is the individual's processing of the 12 bases to 'feel' the environment. (This skandha is sometimes referred to as 'feeling' though that word could be used in an vague way for any of the skandhas from 2 through 4.)

4. Volition (samskara) is the reaction of the will to the objects and may produce aversion, attraction, etc. In other words, the feeling as basis for emotion.

5. Consciousness (vijnana) grasps the qualities of the six objects. It creates a third member of the sets in 2 above. These are designated Visual consciousness, Auditory consciousness, and so on, ending with Mental consciousness. The eighteen now, are called the Eighteen (18) Elements (dhatu).

These five aggregates or formations, the skandas, are not ultimate and eternal in nature but are conditioned. They arise from causes and circumstances. Like all phenomena, they come and go; endure and change and disappear.

Since we are composed of these, we are impermanent. There is no part of us that is eternal. We cannot logically say, "That is mine; I am that; that is my Self"

In Buddhist phenomenology and soteriology, the skandhas (Sanskrit) or khandhas (Pāli, aggregates in English) are any of five types of phenomena that serve as objects of clinging and bases for a sense of self. The Buddha teaches that nothing among them is really "I" or "mine".

In the Theravada tradition, suffering arises when one identifies with or otherwise clings to an aggregate; hence, suffering is extinguished by relinquishing attachments to aggregates. The Mahayana tradition further puts forth that ultimate freedom is realized by deeply penetrating the nature of all aggregates as intrinsically empty of independent existence.

Outside of Buddhist didactic contexts, "skandha" can mean mass, heap, pile, bundle or tree trunk.

Definition

Buddhist doctrine describes five aggregates:

- "form" or "matter" (Skt., Pāli rūpa; external and internal matter. Externally, rupa is the physical world. Internally, rupa includes the material body and the physical sense organs.

- "sensation" or "feeling" (Skt., Pāli vedanā; Tib. tshor-ba): sensing an object as either pleasant or unpleasant or neutral.

- "perception", "conception", "apperception", "cognition", or "discrimination" (Skt. samjñā, Pāli saññā, Tib. 'du-shes): registers whether an object is recognized or not (for instance, the sound of a bell or the shape of a tree).

- "mental formations", "impulses", "volition", or "compositional factors" (Skt. samskāra, Pāli saṅkhāra, Tib. 'du-byed) : all types of mental habits, thoughts, ideas, opinions, prejudices, compulsions, and decisions triggered by an object.

- "consciousness" or "discernment" (Skt. vijñāna, Pāli viññāṇa, Tib. rnam-par-shes-pa):

- In the Nikayas/Āgamas: cognizance, that which discerns

- In the Abhidhamma: a series of rapidly changing interconnected discrete acts of cognizance.

- In some Mahayana sources: the base that supports all experience.

In the Pāli Canon and the Āgamas, the majority of discourses focusing on the five aggregates discusses them as a basis for understanding and achieving liberation from suffering, without describing relationships between the aggregates themselves. Nonetheless, from some canonical discourses, a causal relationship between the five aggregates can be derived. The following (illustrated in the figure to the right) exemplify such relational attributes:

Form (rūpa) arises from experientially irreducible physical/physiological phenomena.

- Form – in terms of an external object (such as a sound) and its associated internal sense organ (such as the ear) – gives rise to consciousness (viññāṇa • vijñāṇa).

- The concurrence of an object, its sense organ and the related consciousness (viññāṇa • vijñāṇa) is called "contact" (phassa • sparśa).

- From the contact of form and consciousness arise the three mental (nāma) aggregates of feeling (vedanā), perception (saññā• saṃjñā) and mental formation (saṅkhāra • saṃskāra).

- The mental aggregates can then in turn give rise to additional consciousness that leads to the arising of additional mental aggregates.

In this scheme, form, the mental aggregates, and consciousness are mutually dependent.

Other Buddhist literature has described the aggregates as arising in a linear or progressive fashion, from form to feeling to perception to mental formations to consciousness.

Parts of a chariot

In the Samyutta Nikaya, the Buddha is recorded as saying that "just as the word 'chariot' exists on the basis of the aggregation of parts, even so the concept of 'being' exists when the five aggregates are available." Thus just as concept of "chariot" is a reification, so too is the concept of "being." The same analysis is applicable to the parts of the chariot; they too are unsubstantial in that they are causally produced, just like the chariot as a whole. The most explicit denial of the substantiality of the components of the being in the early texts is one that was quoted by later prominent Mahayana thinkers:

- All form is comparable to foam; all feelings to bubbles; all sensations are mirage-like; dispositions are like the plantain trunk; consciousness is but an illusion: so did the Buddha illustrate [the nature of the aggregates.

Nagarjuna used ideas of this kind in the agamas to refute the Sarvastivada conception of reality. The simultaneous non-reification of the self and reification of the skandhas has been viewed by some Buddhist thinkers as highly problematic.

In the early texts, the scheme of the five aggregates is not meant to be an exhaustive classification of the human being: rather it describes various aspects of the way an individual manifests. The chariot metaphor is not an exercise in ontology, but rather a caution against ontological theorizing and conceptual realism. Part of the Buddha's general approach to language was to point towards its conventional nature, and to undermine the misleading character of nouns as substance-words.

The skandha analysis of the early texts is not applicable to arahants. A tathāgata has abandoned that clinging to the personality factors that render the mind a bounded, measurable entity, and is instead "freed from being reckoned by" all or any of them, even in life. The skandhas have been seen to be a burden, and an enlightened individual is one with "burden dropped".

Theravada perspectives

Bhikkhu Bodhi (2000b, p. 840) states that an examination of the aggregates has a "critical role" in the Buddha's teaching for multiple reasons, including:

- Understanding the Four Noble Truths: The five aggregates are the "ultimate referent" in the Buddha's elaboration on suffering (dukkha) in his First Noble Truth (see excerpted quote below) and "since all four truths revolve around suffering, understanding the aggregates is essential for understanding the Four Noble Truths as a whole."

- Future Suffering's Cause: The five aggregates are the substrata for clinging and thus "contribute to the causal origination of future suffering."

- Release: Clinging to the five aggregates must be removed in order to achieve release.

Below, excerpts from the Pāli literature will bear out Bhikkhu Bodhi's assessment.

Suffering's ultimate referent

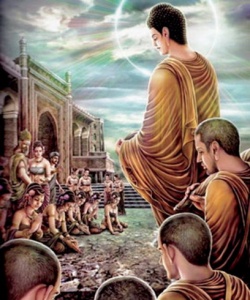

In the Buddha's first discourse, the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, he provides a classic elaboration on the first of his Four Noble Truths, "The Truth of Suffering" (Dukkhasacca):

- The Noble Truth of Suffering (dukkha), monks, is this: Birth is suffering, aging is suffering, sickness is suffering, death is suffering, association with the unpleasant is suffering, dissociation from the pleasant is suffering, not to receive what one desires is suffering—in brief the five aggregates subject to grasping are suffering.

According to Thanissaro:

- Prior to the Buddha, the Pali word khandha had very ordinary meanings: A khandha could be a pile, a bundle, a heap, a mass. It could also be the trunk of a tree. In his first sermon, though, the Buddha gave it a new, psychological meaning, introducing the term clinging-khandhas to summarize his analysis of the truth of stress and suffering. Throughout the remainder of his teaching career, he referred to these psychological khandhas time and again.

In what way are the aggregates suffering? For this we can turn to Khandhavagga suttas below.

In the early texts, the skandhas explain what suffering is. According to Noa Ronkin, "What emerges from the texts ... is a wider signification of the khandhas than merely the aggregates constituting the person. Sue Hamilton has provided a detailed study of the khandhas. Her conclusion is that the associating of the five khandhas as a whole with dukkha indicates that experience is a combination of a straightforward cognitive process together with the psychological orientation that colours it in terms of unsatisfactoriness. Experience is thus both cognitive and affective, and cannot be separated from perception.

As one's perception changes, so one's experience is different: we each have our own particular cognitions, perceptions and volitional activities in our own particular way and degree, and our own way of responding to and interpreting our experience is our very experience. In harmony with this line of thought, Gethin observes that the khandhas are presented as five aspects of the nature of conditioned existence from the point of view of the experiencing subject; five aspects of one's experience. Hence each khandha represents 'a complex class of phenomena that is continuously arising and falling away in response to processes of consciousness based on the six spheres of sense. They thus become the five upādānakhandhas, encompassing both grasping and all that is grasped.'"

The Samyutta Nikaya contains the Khandhavagga ("The Book of Aggregates"), a book compiling over a hundred suttas related to the five aggregates. Typical of these is the Upadaparitassana Sutta ("Agitation through Clinging Discourse," SN 22:7), which states:

- ...[T]he instructed noble disciple ... does not regard form or other aggregates as self, or self as possessing form, or form as in self, or self as in form. That form of his changes and alters. Despite the change and alteration of form, his consciousness does not become preoccupied with the change of form.... [T]hrough non-clinging he does not become agitated." (Trans. by Bodhi, 2000b, pp. 865-866.)

Put another way, if we were to self-identify with an aggregate, we would cling (upadana) to it; and, given that all aggregates are impermanent (anicca), it would then be likely that at some level we would experience agitation (paritassati), loss, grief, stress, or suffering (see dukkha). Therefore, if we want to be free of suffering, it is wise to experience the aggregates clearly, without clinging or craving (tanha), apart from any notion of self (anatta).

Many of the suttas in the Khandhavagga express the aggregates in the context of the following sequence:

- An uninstructed worldling (assutavā puthujjana)

- An instructed noble disciple (sutavā ariyasāvaka) does not regard form as self and so on, and thus when form changes, dukkha does not arise. (Note: in each of the suttas where the above formula is used, subsequent verses replace "form" with each of the other aggregates: sensation, perception, mental formations and consciousness.)

But how does one become aware of and then let go of one's identification with or clinging to the aggregates? Below is an excerpt from the classic Satipatthana Sutta that shows how traditional mindfulness practices can awaken understanding, release and wisdom.

Release through aggregate-contemplation

In the classic Theravada meditation reference, the "Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta" ("The Foundations of Mindfulness Discourse," MN 10), the Buddha provides four bases for establishing mindfulness: body (kaya), sensations (vedana), mind (citta) and mental objects (dhamma). When discussing mental objects as a basis for meditation, the Buddha identifies five objects, including the aggregates. Regarding meditation on the aggregates, the Buddha states:

- How, monks, does a monk live contemplating mental objects in the mental objects of the five aggregates of clinging?

- Herein, monks, a monk thinks, "Thus is material form; thus is the arising of material form; and thus is the disappearance of material form. Thus is feeling; thus is the arising of feeling; and thus is the disappearance of feeling. Thus is perception; thus is the arising of perception; and thus is the disappearance of perception. Thus are formations; thus is the arising of formations; and thus is the disappearance of formations. Thus is consciousness; thus is the arising of consciousness; and thus is the disappearance of consciousness."

- ...Or his mindfulness is established with the thought, "Mental objects exist," to the extent necessary just for knowledge and mindfulness, and he lives detached, and clings to nothing in the world. Thus also, monks, a monk lives contemplating mental objects in the mental objects of the five aggregates of clinging. (Nyanasatta, trans., 1994.)

Thus, through mindfulness contemplation, one sees an "aggregate as an aggregate"—sees it arising and dissipating. Such clear seeing creates a space between the aggregate and clinging, a space that will prevent or enervate the arising and propagation of clinging, thereby diminishing future suffering

As clinging disappears, so too notions of a separate "self." In the Mahasunnata Sutta ("The Greater Discourse on Emptiness," MN 122), after reiterating the aforementioned aggregate-contemplation instructions (for instance, "Thus is form; thus is the arising of form; and, thus is the disappearance of form"), the Buddha states:

- When he a monk abides contemplating rise and fall in these five aggregates affected by clinging, the conceit "I am" based on these five aggregates affected by clinging is abandoned in him.... (Nanamoli & Bodhi, 2001, p. 975.)

In a complementary fashion, in the Buddha's second discourse, the Anattalakkhana Sutta ("The Characteristic of Nonself," SN 22:59), the Buddha instructs:

- Monks, form is nonself. For if, monks, form were self, this form would not lead to affliction, and it would be possible to [[[Wikipedia:manipulate|manipulate]]] form [in the following manner: "Let my form be thus; let my form not be thus...." [Identical statements are made regarding feeling, perception, volitional formations and consciousness.]

- ...Seeing thus [for instance, through contemplation], monks, the instructed noble disciple becomes disenchanted with form [and the other aggregates.... Being disenchanted, he becomes dispassionate. Through dispassion [his mind is liberated. (Bodhi, 2005a, pp. 341-2.)

As seen below, the Mahayana tradition continues this use of the aggregates to achieve self-liberation.

Mahayanist perspectives

In one of Mahayana Buddhism's most famous declarations, the aggregates are referenced:

What does this mean? To what degree is it a departure from the aforementioned Theravada perspective? Moreover, more generally, how are the aggregates used in the Mahayana literature? These questions are addressed below.

The intrinsic emptiness of all things

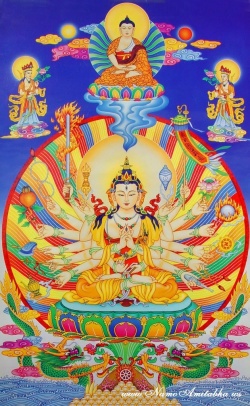

The Sanskrit version of the classic "Prajnaparamita Hridaya Sutra" ("Heart Sutra") begins:

| The noble Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva, | Arya avalokiteshvaro bodhisattvo |

| while practicing the deep practice of Prajnaparamita | gambhiran prajna-paramita caryan caramano |

| looked upon the Five Skandhas, | vyaavalokayati sma panca skandhas |

| ...seeing they were empty of self-existence.... | tansh ... svabhava shunyan pashyati sma.... |

- In the Theravada canon, when "emptiness of self" is mentioned, the English word "self" is a translation of the Pali word "atta" (Sanskrit, "atman"); in the Sanskrit-version of the Heart Sutra, the English word "self-existence" is a translation of the Sanskrit word "sva-bhava".

In other words, whereas the Sutta Pitaka typically instructs one to apprehend the aggregates without clinging or self-identification, Prajnaparamita leads one to apprehend the aggregates themselves as having no intrinsic reality.

In the Heart Sutra's second verse, after rising from his aggregate meditation, Avalokiteshvara declares:

- form does not differ from emptiness, emptiness does not differ from form. The same is true with feelings, perceptions, mental formations and consciousness.

Thich Nhat Hanh interprets this statement as:

- Form is the wave and emptiness is the water.... [W]ave is water, water is wave.... [T]hese five aggregates contain each other. Because one exists, everything exists.

Red Pine comments:

- That form is empty was one of the Buddha's earliest and most frequent pronouncements. But in the light of Prajnaparamita, form is not simply empty, it is so completely empty, it is emptiness itself, which turns out to be the same as form itself.... All separations are delusions. But if each of the skandhas is one with emptiness, and emptiness is one with each of the skandhas, then everything occupies the same indivisible space, which is emptiness.... Everything is empty, and empty is everything

Tangibility and transcendence

Commenting on the Heart Sutra, D.T. Suzuki notes:

- When the sutra says that the five Skandhas have the character of emptiness ..., the sense is: no limiting qualities are to be attributed to the Absolute; while it is immanent in all concrete and particular objects, it is not in itself definable.

That is, from the Mahayana perspective, the aggregates convey the relative (or conventional) experience of the world by an individual, although Absolute truth is realized through them.

The tathagatagarbha sutras, on occasion, speak of the ineffable skandhas of the Buddha (beyond the nature of worldly skandhas and beyond worldly understanding), and in the Mahayana Mahaparinirvana Sutra the Buddha tells of how the Buddha's skandhas are in fact eternal and unchanging. The Buddha's skandhas are said to be incomprehensible to unawakened vision.

Vajrayana perspectives

The Vajrayana tradition further develops the aggregates in terms of mahamudra epistemology and tantric reifications.

The truth of our insubstantiality

Referring to mahamudra teachings, Chogyam Trungpa (Trungpa, 2001, pp. 10–12; and, Trungpa, 2002, pp. 124, 133-4) identifies the form aggregate as the "solidification" of ignorance (Pali, avijja; Skt., avidya), allowing one to have the illusion of "possessing" ever dynamic and spacious wisdom (Pali, vijja; Skt. vidya), and thus being the basis for the creation of a dualistic relationship between "self" and "other."

According to Trungpa Rinpoche (1976, pp. 20–22), the five skandhas are "a set of Buddhist concepts which describe experience as a five-step process" and that "the whole development of the five skandhas...is an attempt on our part to shield ourselves from the truth of our insubstantiality," while "the practice of meditation is to see the transparency of this shield." (ibid, p. 23)

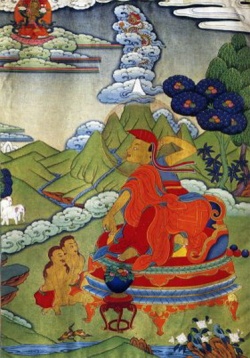

Bardo deity manifestations

Trungpa Rinpoche writes (2001, p. 38):

- [S]ome of the details of tantric iconography are developed from abhidharma [that is, in this context, detailed analysis of the aggregates. Different colors and feelings of this particular consciousness, that particular emotion, are manifested in a particular deity wearing such-and-such a costume, of certain particular colors, holding certain particular sceptres in his hand. Those details are very closely connected with the individualities of particular psychological processes.

Perhaps it is in this sense that the Tibetan Book of the Dead (Fremantle & Trungpa, 2003) makes the following associations between the aggregates and tantric deities during the bardo after death:

- The blue light of the skandha of consciousness in its basic purity, the wisdom of the dharmadhātu, luminous, clear, sharp and brilliant, will come towards you from the heart of Vairocana and his consort, and pierce you so that your eyes cannot bear it. [p. 63]

- The white light of the skandha of form in its basic purity, the mirror-like wisdom, dazzling white, luminous and clear, will come towards you from the heart of Vajrasattva and his consort and pierce you so that your eyes cannot bear to look at it. [p. 66]

- The yellow light of the skandha of feeling in its basic purity, the wisdom of equality, brilliant yellow, adorned with discs of light, luminous and clear, unbearable to the eyes, will come towards you from the heart of Ratnasambhava and his consort and pierce your heart so that your eyes cannot bear to look at it. [p. 68]

- The red light of the skandha of perception in its basic purity, the wisdom of discrimination, brilliant red, adorned with discs of light, luminous and clear, sharp and bright, will come from the heart of Amitābha and his consort and pierce your heart so that your eyes cannot bear to look at it. Do not be afraid of it. [p. 70]

- The green light of the skandha of concept (samskara) in its basic purity, the action-accomplishing wisdom, brilliant green, luminous and clear, sharp and terrifying, adorned with discs of light, will come from the heart of Amoghasiddhi and his consort and pierce your heart so that your eyes cannot bear to look at it. Do not be afraid of it. It is the spontaneous play of your own mind, so rest in the supreme state free from activity and care, in which there is no near or far, love or hate. [p. 73]

Relation to other Buddhist concepts

Other fundamental Buddhist concepts associated with the five skandhas include:

- It is through the five skandhas that the world (saṃsāra) is experienced, and nothing is experienced apart from the five skandhas.

Three Characteristics

- It is through the five skandhas that impermanence (anicca • anitya) is experienced, that suffering (dukkha • duḥkha) arises, and that "non-self" (anattā • anātman) can be realized.

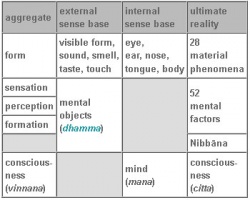

- The Abhidhamma and post-canonical Pali texts create a meta-scheme for the Sutta Pitaka's conceptions of aggregates, sense bases and elements. This meta-scheme is known as the four paramatthas or four ultimate realities:

- consciousness

- mental factors

- material phenomena

- Nibbāna

- The mapping between the aggregates, the sense bases (see below) and the ultimate realities is represented in the chart to the right.[63]

- The first five external sense bases (that is, the sense objects of visible form, sound, smell, taste and touch) are part of the form aggregate and the mental sense object (that is, mental objects) overlap the first four aggregates (form, feeling, perception and formation).

- The first five internal sense bases (that is, the sense organs of eye, ear, nose, tongue and body) are also part of the form aggregate and the mental sense organ (mind) is comparable to the aggregate of consciousness. While the benefit of meditating on the aggregates is overcoming wrong views of the self (since the self is typically identified with one or more of the aggregates), the benefit of meditation on the six sense bases is to overcome craving (through restraint and insight into sense objects that lead to contact, feeling and subsequent craving).[64]

Twelve Nidanas / Dependent Origination

- The Twelve Nidanas describe twelve phenomenal links by which suffering is perpetuated between and within lives. Embedded within this model, four of the five aggregates are explicitly mentioned in the following sequence: mental formations (saṅkhāra • saṃskāra) condition consciousness (viññāṇa • vijñāna) which conditions name-and-form (nāma-rūpa)[28] which conditions the precursors (saḷāyatana, phassa • sparśa) to sensations (vedanā) which in turn condition craving (taṇhā • tṛṣṇā) and clinging (upādāna) which ultimately lead to the "entire mass of suffering" (kevalassa dukkhakkhandha). Overlaying this chain of conditioning on top of "The Five Aggregates" diagram at the top of this article, the interplay between the five-aggregates model of immediate causation and the twelve-nidana model of requisite conditioning becomes evident, for instance, underlining the seminal role that mental formations have in both the origination and cessation of suffering.

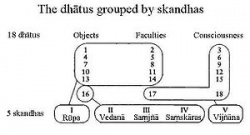

- The eighteen dhatus function through the five aggregates. The eighteen dhatus can be arranged into six triads, where each triad is composed of a sense organ, a sense object and sense consciousness. In regards to the aggregates:

- The first five sense organs (eye, ear, nose, tongue, body) are derivates of form. The sixth sense organ (mind) is part of consciousness.

- The first five sense objects (visible forms, sound, smell, taste, touch) are also derivatives of form. The sixth sense object (mental object) includes form, sensation, perception and mental formations.

- The six sense consciousness are the basis for consciousness.

The dhātus grouped according to skandha

The Eighteen DhātusThe table below briefly cites Buddhist primary sources that characterize different aspects of the aggregates. This table is by no means exhaustive.

Some references to the aggregates in Buddhist primary sources (Abbreviations: MN = Majjhima Nikaya; SN = Samyutta Nikaya; Vism = Visuddhimagga.)

| Aggregate | Description | source |

|---|---|---|

| rūpa (Form) | ||

| It is the four Great Elements (mahābhūta) -- earth, water, fire, wind—and their derivatives. |

SN 22.56 | |

| It is afflicted with cold, heat, hunger, thirst, flies, mosquitoes, wind, sun, reptiles. |

SN 22.79 | |

| The cause, the condition and the delineation are the four Great Elements. |

MN 109 | |

| There are 24 kinds of "derived" forms (upādāya rūpam). |

Vism XIV.36ff | |

| vedanā (Feeling) | ||

| It is feeling born of contact (phassa) with eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, mind. |

SN 22.56 | |

| It feels pleasure, pain, neither-pleasure-nor-pain. | SN 22.79 | |

| The cause, the condition and the delineation are contact (phassa). |

MN 109 | |

| As individual experience, can be analyzed as bodily pleasure, bodily pain, mental joy, mental grief, equanimity. |

Vism XIV.127 | |

| saññā (Perception) |

||

| It is perception of form, sound, smell, taste, tactile sensation, mental phenomena. |

SN 22.56 | |

| It perceives blue, yellow, red, white. | SN 22.79 | |

| The cause, the condition and the delineation are contact (phassa). |

MN 109 | |

| Functions to make a "sign" for perceiving in the future that "this is the same." |

Vism XIV.130 | |

| saṅkhāra (Formation) |

||

| It is volition regarding form, sound, smell, taste, tactile sensation, mental phenomena. |

SN 22.56 | |

| It constructs constructed forms, feelings, perceptions, volitional formation, consciousness. |

SN 22.79 | |

| The cause, the condition and the delineation are contact (phassa). |

MN 109 | |

| Characterized by "forming," functions to "accumulate," manifests as "intervening." |

Vism XIV.132 | |

| viññāṇa (Consciousness) |

||

| It is eye-, ear-, nose-, tongue-, body-, mind-consciousness. |

SN 22.56 | |

| It cognizes what is sour, bitter, pungent, sweet, sharp, mild, salty, bland. |

SN 22.79 | |

| The cause, the condition and the delineation are name-and-form (nāmarūpa). |

MN 109 | |

| There are 89 kinds of consciousness. | Vism XIV.82ff |

Source

Or Five Aggregates, the five groups of elements (Dharmas) into which all existences are classified in early Buddhism, that is, the five components of an intelligent beings, or psychological analysis of the mind:

- 1. Matter or Form (rupa) - the physical form responded to the five organs of senses, i.e., eye, ear, nose, tongue and body

- 2. Sensation or Feeling (vedana) - the feeling in reception of physical things by the senses through the mind

- 3. Recognition or Conception (sanjna) - the functioning of mind in distinguishing and formulating the concept

- 4. Volition or Mental Formation (samskara) - habitual action, i.e., a conditioned response to the object of experience, whether it is good or evil, you like or dislike

- 5. Consciousness (vijnana) - the mental faculty in regard to perception, cognition and experience