Chöd-practice

Introduction

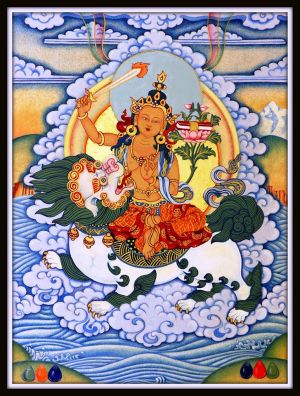

There is something attractively romantic about the mysterious, shamanic practice of ancient Chöd (Skt: ccheda-sadhana, Tib: gChod sgrub thabs). Chöd-practice, cutting through delusion's root, is haunting, strange and mysteriously beautiful all at the same time. This practice involves a whirling dance, accompanied by drum and bell. As the following essay will recount, Chöd is a special type of mysticism that unites shamanic practice with profound yogic meditation.

Chöd has long been a way of seeking direct and personal experiences of mind and divinity outside of conventional and institutional frameworks. In Chöd-practice, the yogi or yogini journeys into the night world the dangerous reg ions of ghosts, spirits and the damned, to bless all souls lost for a

time on the wheel of existence. The selflessness of the practitioner's compassion, his or her contact with spirits of the other-world, and the making of himself into a vehicle of healing, all tends to become a path for the hero to win the noetic Mind -Jewel of true awakening. Chöd is a practice that combines Buddhist meditation with ancient Tibeto-Siberian shamanic ritual. The "liturgy" of Chöd is sung to the accompaniment of

drum, bell and a thigh-bone horn. The word "Chöd" means to cut through, to "chop," and what i s chopped off is ultimately the Ego. Initially this begins with cutting all attachment to the body and to material things. When identification with the finite m ind-body complex is let go of, then the pure awareness is set free to perceive reality as it really is. The whole world becomes potent as a place of blessing p wer and awareness.

Pa Dampa Sangye, the "Father" of Chöd

Pa Dampa Sangye was a dark skinned South Indian saddhu who lived in the eleventh century. He came to Tibet and introduced a system of meditation called Zhi-jye, the pacification of suffering. The Zhi-jye teachings are founded on the doctrine of Transcendental Wisdom (Arya-prajna-paramita) and meditation. Dampa Sangye visited Tibet five times at widely spaced intervals and imparted teachings to disciples more numerous than all the stars visible in the night sky. He met with the poet-saint Milarepa toward the end of the latter's life.

Pa Dampa Sangye is said, according to one tradition, to have been the reincarnation of Bodhidharma (c. 560 AD) who introduced Zen Buddhism into China. Another figure in history who is credited with representing an earlier lifetime of Padampa Sangge is Kamalashila (c. 800 AD). Kamalashila was the disciple of the learned sage Shantiraksita. After the death of the latter, Kamalashila came to Tibet to carry on his master's work.

During Kamalashila's stay in Tibet a fierce debate grew up around a Chinese monk named Hwa-shang Mahayana, who was preaching very favorably amongst the Tibetan people. Hwa-shang represented the "Cittamatra" point of view, while Kamalashila taught the view known as "Madhyamaka-Yogacara." It is hard to know from the differing accounts exactly who "won" this debate, but it is said that after the debate the Chinese faction poisoned Kamalashila, and he died in Tibet. According to the Ri-tro Chos, or Hermitage Instructions, of Karma Chagme, the consciousness o f Kamalashila was then reborn in the far south of India amongst the dark skinned Tamil people. He grew up to become a very saintly Tamil sage and saddhu. It was in this form that he eventually returned to Tibet as the wisdom-master "Father" Dampa Sangye.

When Pa Dampa Sangye came to Tibet, he found the people in the county of Tingri, which is near Mt. Everest on the Tibetan side, to be especially amenable to his instruction. He therefore settled in Tingri and established a school of Yoga practice there. A young Tibetan woman named Machig Labdrön (1055-1153) was one of those who became his disciple.

Machig and her guru Dampa Sangye are generally viewed as the founders of the Chöd system. However, it would appear that Chöd itself is a blending together of Pa Dam pa Sangye's teachings and Machig's native inheritance. Pa Dampa Sangye taught Ma chig the rudiments of Mahamudra meditation. Fairly soon after her meeting with P a Dampa Sangye, the Tibetan woman Machig Labdrön went to live in Central Tibet, where she took up residence in a lonely cave and set herself to practice meditation.

Following her guru's instruction, she began by spending the first year completing the preliminary exercises (ngön-dro). Afterwards she went to a place called Zang -ri Khar-mar, which then became her residence for the rest of her life. It was t here that she developed Chöd as a definite system of practice.

Another leading disciple of Pa Dampa Sangye was a Tibetan known as Kyton Sonam Lama. It was the latter who, we are told, would come and visit Machig in her cave residence, and pass along further teachings from the guru Dampa Sangye to her. Through the interaction of these three, the Chöd system grew into an amazingly beautiful and profound method of spiritual development

Chöd, combining Yoga and Shamanism

Chöd therefore is a subtle blend of the Buddhist path to enlightenment (as represented by the Mahamudra-master Dampa Sanggye) brought from India, and an ancient f orm of Shamanic ritual (introduced by the woman Machig Labdrön) that was native to Tibet. It was the merging of these two streams which resulted in the actual emergence of Chöd as a practice used by yogins today, in their desire to gain Enlightenment by the shortest possible path. Thus Chöd is a more advanced form of shamanism, which has been raised to a higher level of perfection by virtue of its blending together with the innermost teachings of Mahamudra.

Machig herself said:

"My system of Chöd consists of the intrinsic teachings of Mahamudra. This Mahamudr a cannot be explained in words. Yet, although it is beyond verbal expression, it may be indicated [by means of the symbolism of Chöd]."

Traditionally speaking, the path of yoga is a path of self-mastery and the yogin is one, whether male or female, who aims for perfect Enlightenment. This is not a shamanic path.

The way of the shaman, on the other hand, has always been a path involving communion with other powers and spirits, and in many cases the attainment of Enlightenment may not be perceived as its goal at all. A shaman or shamaness, by definit ion (vide Prof. Hutton, Shamans, Hambledon & London, London 2001), is "someone w ho works with spirits to help others." The shaman channels these spirits, to accomplish definite ends, such as healing or gaining access to knowledge of some kind. But Chöd combines the path of Enlightenment and Shamanism into one.

Chöd's special appeal for women

Chöd practice has had a special appeal for women, perhaps because it was largely founded by a woman saint (Machig Labdrön was the "Mother" of Chöd). All down through history, women have been spiritual leaders in the Chöd tradition. Besides having been created by Machig Labdrön herself, and also attributed to Princess Yeshe Tsogyal, other famous woman figures in the Chöd tradition include Shukseb Zangmo (1852

1953, herself considered to be an incarnation of Machig), Jomo Menmo (1248-1283) , Jetsunma Mingyur Paldron (1699-1769, the daughter of Terdag Lingpa), Jetsunma Thinley Chodron, a teacher of Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo, and Sera Khadro Kunzang Wangmo (1899-1952). At the Shukseb Convent near Lhasa, more than

one hundred Kagyu nuns still follow our tradition of the mKha'-'groi Gad-rGyangs Chöd, a practice revealed by the great mystic Jigme Lingpa. The invisible dimension

Chöd is a spiritual practice conducted by the yogini (or yogi) alone in the wilderness, where she must learn to face every fear and every bit of ego-clinging with in herself. Indeed, to accomplish this, she (or he) is instructed to deliberately go to places that inspire supernatural dread.

Traditionally, once the yogini h as found a wild and lonely spot, which is supposed to be a place that seems imbu ed with power or reportedly haunted by

spirits, not to mention wild beasts, she sets up a tent. Erecting this tent is not a casual act it is done ritually, and ea ch of the four tent-pegs is driven into the ground, while mindful of the symbolic act of empowering the four directions: east, south, west and north, each having a specific color

and meaning. As night falls, the yogini will begin to sing th e ancient melodious chant, signifying the start of the meditation. She must face the spirits of nature, the "elementals," and the ghosts of the dead, which the ritual evokes, and dominate them; or, failing that, be dominated in turn, which might

mean becoming possessed, possibly leading to madness or even death. According to the beliefs of psychic and Tibetan mystics, the physical world perceived by our five senses is only a small portion of the total reality in which w e live. All around us are invisible entities; types of "beings" or "spirits" which we cannot see. These entities exist in parallel, but separate, dimensions or worlds of their own. Nevertheless all these "parallel" realms are part of the sa me planet. For example, what appears as a river to us, might

seem to be a current of color and energy within the realm of the Shining Devas. Again the same rive r would seem to be something like a current of molten iron lava to an evil spirit, or "demon", trapped in its own self-created hell. For just like human beings, so too spirits can be either good or evil.

A good spirit is one which radiates love outwards from itself towards all others with whom it is connected. And the "higher" the type of spirit, the more it is intrinsically connected with all sentient beings. An evil spirit, on the other h and, is one which has become closed upon itself, isolated from the

whole, and lives tightly turned inwards on its own neurosis. The tighter and darker becomes t he suffering of that spirit, the more demonic its nature. But according to the Adepts of Chöd, nothing is permanent. A spirit lost for a time in one of the hideous "lower realms" of suffering, may always be healed (either through time itself, or by the intervention of the Chödpa) and gradually lifted up into the Light. Thus the work of the Chödpa, as of the saint who prays constant ly for the welfare of others, is to transform spirits of darkness into angels of light.

According to the Buddha our planet consists of six parallel "levels" of existence, or six bio-zones. If we look at this from our human perspective, we can, for example, talk of the mineral realm, the vegetable realm, the animal realm and the human realm. But is that all? According to the Sages, there is

also a twilight or astral realm parallel with the vegetable realm, which is called the ghost re alm. This is not a terribly bad zone to experience, but it does seem to be a place of great longing and considerable confusion. The mental state of this ghost r ealm is dream like, grey, vegetative, and filled

with a yearning hunger. There a re better places indeed to find oneself after death, and indeed, the sages say t hat one such place is the superior astral, or "heavenly" realm, where the consciousness emerges as a shining spirit called an angel, or Deva.

Angels are classified, in Buddhism, into two categories. What we might call inferior angels and superior angels. In Christianity these two orders are known as angels and archangels. In Judaism they have long been called beni-Elohim (sons of the gods) and Elohim (gods). The ancient Buddhist terminology

is very close to the latter, since in Buddhism we call these spirits Devaputra (also called Asura s), which literally means "sons of the Devas," and Devas (or Suras). The word "d eva" or "sura" literally means a "shining being".

Where do the Devas live? Those adepts who can see with clairvoyant sight the higher vibrational levels, experience the Devas as luminous, vaguely humanoid forms of intelligence, seemingly abiding in the mountains and in forest groves or in ethereal paradises. In most cases, however, these shining spiritual beings appear to live "above" the physical plane; when we experience them, they seem to "com e down" to our plane, so as to commune with us. Temples and shrines are also vie wed as places where these Devas appear to come down to earth, as if in a sense t hese sacred "power places" are inter-dimensional portals between the physical an d nonphysical world.

After death, according to the Buddhist view, a being can take birth in any of the six realms. Thus, in one's next existence, once death has occurred to the body , you might find yourself emerging into a fresh luminous existence as an Asura-spirit in a heaven-like realm of color, scent and musical rhythm.

Or, if tortured by unresolved issues from harmful actions which one has done, you may emerge as a dark, violent Demonic-spirit, in the discordant realm described as hell. There are six possible destinies for the consciousness of one who has just died.

Now, these six destinies or bio-zones of this our planetary world, according to the Tibetan system, are as follows:

Lha (Skt: deva) - superior Shining Ones, or archangel realm Lha-ma-yin (Skt: asura) - inferior Shining Ones, or angel realm Mi (Skt: nara) - the Human realm Du-do (Skt: Tiryak) - the Animal realm Yi-dag (Skt: preta) - the Ghost realm = Vegetable realm Nyal-kham (Skt: Naraka) - the Hell realm = Mineral realm It may be noted that the Lha and Lha-ma-yin dwell in what people of different cultures have all described as "heaven realms." The humans and animals abide together in what to us is the "physical realm". And ghosts and demons apparently roam what might be called "the lower astral" domain.

When animal's die, they too may become elemental spirits chained to the physical location where death occurred. These unseen entities are the Elementals spoken of by occultists and clairvoyants. These are the fairies and sprites of folklore . In Tibetan teachings they are sometimes categorized as follows:

Dri-za (Skt: gandharva) - sylphs, air elementals Namkha'lding (Skt: garuda) - phoenix, fire elementals kLu (Skt: naga) - dragons, water elementals gNod-sbyin (Skt: yakshas) - gnomen, earth elementals But there are many other types of elemental spirits mentioned in Buddhist lore, too. There are the Mi-'am-c'i (Kinnara), or lovely celestial musicians, and the Srin-po (Rakshasa) which appear as dangerous fire elementals. There are 'Byung-p o (Bhuta) and

harmful Sa-za (pisaca), spirits of the jungle, the cremation grounds and the forest, which can cause misfortune, or disease, or insanity. And there are the Gyalpo and the Tsen, powerful ghosts of slain heroes and Lama-sorcerer s, who have died unfulfilled or with a curse on their lips; it is said their thirst for power and vengeance lives on.

Do these good and evil spirits (lha-dre) actually exist, or are they but the imagination of a more primitive culture? The decision has to be yours. Science does not appear to have proved, as yet, the existence of parallel realms, invisible to our telescopes, microscopes and measuring devices. As one grows

spiritually, an awareness of disincarnate and non-incarnate entities is one of the features t hat the mystic develops. But the truth of this experience cannot be proven nor demonstrated to the skeptic. It is simply something that one has to experience an d judge for oneself no one else can say whether it is true or not.

The same goes for death. What happens after death? Some people believe that when the body dies, so does the person, the mind and the consciousness. According to this way of thinking, mind is the product of the physical brain, and when the b rain dies, that is the end. The religions of the world, on the

other hand, have all taught that after death our experience continues. But the different religion s are by no means in complete agreement concerning "how" that continuation will take place. Some insist that the entity will never again return to a human incarnation. Some, though they admit we may be reborn as a human person again, deny t he idea that we can descend to an animal level of rebirth. So there are differing opinions.

Buddhism describes a world in which the mineral "hell" realm is at the bottom of the ladder of evolution, so to speak, and the "deva" realm at the top. The Deva realm is also said to reach further and further upwards, to ever more refined s tates of being. But Buddhism does claim that we can also devolve, and not only e volve. We can go down the scale, as well as rise up it. Contact with those who h ave died, by psychics who are alive, may be able to tell us a

lot more about this so called "next world." But what is true, and what really happens after death, can only be known when death itself intervenes. Until then, it is up to the individual to make his or her own rational judgment.

The yogini in her tent calls the various spirits of the land to her. These she t hen must treat in different ways. The higher beneficial spirits, she may commune with for healing disease, and to do so she will establish a relationship of peace (Tib: zhi-wa, Skt: santika) between herself and those which come

within the sphere of her influence. She may establish a similar relationship with the ghosts (preta) of the dead, but the more confused or troubled ghosts of the spirit world she must help to guide and, as it where, "raise their vibration" (Tib: rgyaspa byed-pa, Skt: paustika) if she is to free them from

their suffering. Tormented spirits, and elementals, have to be subdued (Tib: dbang-'dus, Skt: vasya) and directed. The really evil entities she must learn to dominate, exorcise (Tib: dr ag-shul, Skt: marana) and ultimately liberate. All of this the yogini (or yogi) accomplishes through the means of her Chöd-practice.

At the end, after the dedication of the power which has been generated by the practice, the yogini may make the following prayer:

"May all you spirits and elementals eventually be born as human beings, and in f uture ages, become my disciples. There upon, may the Uncreated Light of pure, original Mind, arise in the consciousness of you beings; and avoiding the erroneous belief in an 'ego', may your consciousness become thoroughly saturated with the gentle moisture of Love and Compassion."

Chöd is an advanced practice

"As in all yoga, so in this," rightly said Evans-Wentz, the British gentleman who was the first to publish a Chöd text into the English language, "the yogi seeks to outstrip the normal, and, to him, over-slow and tedious process of spiritual unfoldment; and, karma permitting, win Freedom, as Tibet's great yogi Milarepa d id, in one lifetime."

Long probationary periods of careful preparation and training under a teacher of Chöd are required before the novice is ready to go forth on his own, to perform t his psychically demanding practice. As Ven Bardok Chusang Rinpoche points out, C höd is not for beginners on the Spiritual Path. Comparing the yogins training to w estern schooling and university, Rinpoche emphasized that Chöd is equivalent to postgraduate work. Done properly, it is a powerful means of cutting delusions roo t, but it is also a dangerous exercise.

Paramount to practicing Chöd the seeker must learn to develop empathic altruism. T he only thing that can dissolve the emotional distance between the Chöd-practitioner and communion with other beings is altruistic love. One really does have to l earn to love everyone and everything. It is exactly for this reason that Chöd-practice is not taught to anyone who has not first undergone the preliminaries (Skt: purvaka, Tib: ngön-dro). This must be especially emphasized for the Westerner.

As most correctly pointed out by the eccentric Russian woman-mystic, Yelena Petrovna Blavatskaya, in the last century:

"All western, and especially English education is instinct with the principle of emulation and competition; each boy is urged to learn more quickly, to outstrip his companions, and to surpass them in every possible way. What is mistakenly called "friendly rivalry" is assiduously cultivated, and the same

spirit is fostered and strengthened in every detail of life. With such ideas 'educated into him ' from his childhood, how can a Westerner bring himself to feel towards his co-students 'as the fingers of one hand'? He who would be a student [of Tibetan occultism] must first be strong enough to kill out in

his heart all feelings of dislike and antipathy to others. How many Westerners are ready even to attempt this in earnest? "In the East the spirit of 'non-separateness' is inculcated [in the monasteries] as steadily from childhood up, as in the West the spirit of rivalry.

Personal ambition, personal feelings and desires, are not encouraged to grow so rampant there. When the soil is naturally good, it is cultivated in the right way, and the child grows into a man in whom the habit of subordination of one's lower to one 's higher self is strong and powerful. In the West men think that their own like s and dislikes of other men and things are guiding principles for them to act up on, even when they do not make of them the law of their lives and seek to impose them upon others."

To accomplish Chöd-practice it is a prerequisite that one develop an unconditional love for all. Such a love cannot be limited only to those we like, or approve o f. Unconditional love means especially a love full of compassion for those who w e least would want to be intimate with. For if we are going to heal others at al l, we shall have to be intimate with them. We will have to share their pain, as also be able to empathically soothe and alleviate their confusion, their suffering, and their active negativity.

Chusang Rimpoche made something of a joke of this. "The novice Chödpa," he said, " is so eager to offer his very own body, to nourish and help the poor misguided evil spirits. But comes along just one mosquito, and then where is his love and compassion for all sentient beings?"

The practitioner has to be trained in Maitri-meditation. The latter is meditation on Love, where all the walls protecting the heart from feeling total, unconditional altruism are systematically torn down. There must be no emotional distancing between the practitioner and the being who is the object of his compassion, w hen he takes up the dangerous, shamanic practice of Chöd. If this empathic love ha s not been thoroughly developed as a basis, the novice at the practice is liable to be overcome and possessed by the very powers which he hopes to work with.

Some Chöd-practice has already been introduced into the West. Consequently we now have some genuine "Chöd-pa" practicing in various places here in America and likewise in Canada. However, something has to be said about some of the practice which has been introduced, but which is not very authentic. In a

number of cases where Chöd is being taught, the profound nature of the exercise is missing. Sadly, when that is the case, the performance is no more than "play acting," and what was for the genuine practitioner in the Himalayas a very real "out of body" experience, and a way of directly dealing with the spirit-world, in America this has be come no more than an imaginary journey.

Students, taking up the practice without real training, are left to merely visuaize themselves going through the performance. It is all pretend. One "pretends" to become the black wrathful Dakini (krodha kali-ma); one "pretends" to leap out through the fontanel into the open space of the spirit-world. But the actual experience is missing. And that is in part because these Western students are not being correctly informed about what the practice is really all about

. The advantage of those who practice Chöd without thoroughly understanding it, is t hat by only play acting the role, they avoid the danger of real contact with the spirit world. The Western student therefore may approach Chöd as a mild form of " self-help" system, with the aim of promoting a feeling of compassion for others. In that sense it cannot but prove to be of some benefit for those practicing it .

Needless to say, Jerome Edon (see: Machig Labdrön and The Foundations of Chöd, Snow Lion, NY 1996) is utterly mistaken when he makes the claim "that in the Chöd tradition there is no trace of either trance or ecstasy, nor of what in shamanistic terminology is referred to as an initiatory journey."

Frequently, once a system of spiritual practice is "popularized" in the West, it s power becomes watered down. This has happened to Hatha-yoga, the form of yoga devised by Mahasiddha Gorakhnath which uses physical postures and movements of t he body to trigger the Kundalini (Tib: gTu-mo) experience. With the correct physical postures (asanas), Gorakhnath's yoga was a dangerous exercise taught only t o advanced initiate's of his Nath Siddha School. However,

having been brought to the West, and then re-introduced back into India, as a system of physical exercises for the purpose of inducing health, the whole system has been so changed as to become quite ineffective as a tool for Kundalini. Thus, it is fairly "safe"3 .

The student of Chöd must receive proper transmission and permission to practice Chöd . This transmission is a spiritual blessing that is passed down in an unbroken lineage through a line of wisdom-masters, and as such protects the student on thi s most advanced, critical path of endeavor 4.

Furthermore, the disciple needs to learn the proper intonation of the mystic mantras; the manner for beating the drum, the sounding of the spirit-evoking horn made of human thighbone, and the rhythm of the bell. Each Chöd transmission has a certain specific "liturgy" of its own, and this has to be carefully adhered to.

With genuine Chöd, the whole practice must be committed to memory. The steps of the dance in relation to the various geometrical arenas have to be mastered. And t he spirits, both those that are safe as well as those that are distinctly evil, need to be truly evoked. To accomplish the latter, it is said that it is best to perform the exercise in a place well known to be haunted, such as a cemetery. S o, after all the acts of the performance has been thoroughly mastered, the Lama sends the student out, to go to a haunted spot alone. It is then that she or he, in the dark of the night, has to confront not only all the supernatural fears created by such a place, but also actual spirits.

Giving up of the Self

The practice of Chöd means that the yogini or yogi meditates in such a way as to become, stage by ever deepening stage, absorbed into the whole process of surrendering and offering one's body and self. This selfless offering only really occur s when the practitioner is finally absorbed into trance (samadhi) through the us e of the ritual, aided in particular by the steady beat of the drum and bell. Th e adept of Chöd, uttering a secret mantra, then leaves his body, mounting the sky in the aspect of the Secret Gnostic Dakini, and there, in the mind-made-body (ma nomayadeha) of the Dakini, Who is black as night itself, she severs the metaphysical mind-body complex so as to offer it to the communing spirits (lha-dre), goo d and bad. What is really given to the

spirits to feast on, is the energy used t o bind the Ego in the mind-body form. In devouring this, they become liberated, as does the Siddha herself. The "offering up of one's body" in this fashion is done not in this world, but i n the spirit dimension of virtual space. If done properly, it can effect healing , and many a Chödpa has been called in to arrest the course of a plague or epidemi c. Chödpas have also been requested to make their offering-of-

self on behalf of the dead. Thus, in Tibet, we frequently see Chödpas present on the occasion of a fun eral. However, it must be kept in mind that the ultimate purpose of Chöd is not only an act aimed at helping others, but much more importantly, it is for the generation of Enlightenment. The Enlightened-mind is, however, a mind of utterly selfless love. So in that sense, the two aims go hand in hand. Real love and compassion cannot be artificial; it has to be absolutely real. The Chödpa therefore applies wisdom as a remedy to "cut through" ignorance, which is his own erroneous notion o f ego.

The real demons that are slain by Chöd

What common folk think of as a demon is something very, very big, and colored de ep black. Who ever sees one of these is truly terrified and trembles from head t o foot," said Machig Labdrön. "Nevertheless, no such demons really exist apart fro m the mind!"

The truth of the matter is this: Anything whatsoever that obstructs or limits the attainment of Liberation is a demon. Even our loving and affectionate relative s can become "demons" for us, if they are obstructing our spiritual evolution. T hus the greatest of all "demons" is actually the Demon of Ego, which is your own sense of a permanent, independent self, separate from all others. If you do not slay this clinging to a self, then good and bad spirits (lha-dre) will just kee p lifting you up and letting you down.

Machig Labdron defined four types of psychological "demons" that must be exorcised by the practitioner of Chöd.

The first is what she called the Tangible Demon (thogs bcas bdud), which is the error of mistakenly grasping at the objects of sense-perception as if the world were an objective reality separate from consciousness. We have to come to experience the fact that all "outer" appearance takes place within Mind. As long as the neophyte has not realized the holographic and entirely subjective nature of existence, and continues to view phenomena as something other than Mind itself, th en reality is a "tangible demon" which must be cut through.

The second of her "four demons" is called the Intangible Demon (thogs med bdud). This is not external, but rather, stands for the positive and negative thoughts , feelings and impulses, which are within ourselves. These reactions and emotion

s, such as pain, fear, jealousy, greed, dislike of others, and so forth, are an Intangible Demon that has to be slain. The adept who accomplishes overcoming thi s inner demon is described as fearless.

The third is the Demon of Manic-Inflation (dga' brod bdud) or of "Exultation", which can be born from acquiring occult powers or special blisses in the meditation experience. Manic-Inflation is a sense of power, a heightened sense of spirit ual worth or supernatural ability. It is the presumption of spiritual superiority 5. In meditation it is common to be thrilled by the energy and feeling of magnified glory, by the divine grace flooding through all the cells of one's being. T here is nothing wrong with such bliss, but the adept has to become unattached to the experience.

The fourth demon described by Machig Labdrön is the Demon of Pride (snyem byed kyi bdud), the Demon of Ego itself. This latter, she said, is the root of all the other three, for ultimately the Demon which must be killed is our own self. As so on as one cuts off the Demon of Ego, all other demons are simultaneously conquer ed. Immediately the Demon of Ego is slain, the person becomes Enlightened at once.

"Using obstacles [i.e., demons] on the path is the meaning of Chöd-practice. Realizing that everything is mind, not the slightest object to cut through. When the emptiness of mind itself is realized, then no duality between "cutter" and "cut" remains. When this nonduality is realized, then angels and demons vanish and on e is left like a thief in an empty house, with nothing to cut." (Jigme Chokyi Senge)

Though Chöd may appear on the surface like a shamanic rite, the Yoga of Chöd follows the same process of mystical development as in other systems of Buddhism. Machi k Labdrön herself explains this as follows:

"Once the yogini has recognized the non-existence of inner and outer phenomena, after the psychic energy (prana-vayu) has entered and started to rise up the central nervous system (avadhuti), then she will begin to experience extraordinary states of ecstasy and [eventually] the Clear Light itself. Knowledge of the three times, and clairvoyant perception of events near and far, will begin to emerge . Having attained the uncreate Clear Light, then the yogini will acquire an abil ity of mind to aid vast numbers of sentient beings everywhere... The instruction lineage that explains how to accomplish this is that called the Chöd of Mahamudra ."6

To cut the ego off at the root, where it is rooted in the unconsciousness, and likewise to cut off the five root afflictions greed, hatred, confusion, pride and avarice is the real meaning of Chöd. For the yogini this means also to cut through hope and fear, all of which possesses and controls ordinary individuals just like good or evil spirits. To be free of that, is to be Liberated. This is the ultimate value of Chöd.

Conclusion

The system of Chöd which comes down to us from the Venerable Bardok Chusang Rimpoche and from Khanchen Palden Sherab Rimpoche to the Dharma Fellowship is the transmission of Yeshe Tsogyal revealed by Jigme Lingpa, known as the "Far-reaching Laughter of the Dakini".

(mKha'-'groi Gad-rGyangs), a profound Chöd-practice from the Longchen Nyingtig tradition. Thanks to the brilliant translation work and musical ability of David M olk and his wife, who reside in Big Sur, we are able to learn to sing this Chöd-practice in English, while retaining the ancient Tibetan shamanic melody. Since it is an advanced practice, it may only be taught to members of the Fellowship who

are deemed ready to properly take it on. This beautiful and uplifting ritual is a profound meditation with manifold transcendental ramifications, yielding to t he highest of insights. Through this Chöd-practice many a western person can now r apidly progress on the path of Enlightenment and win through to complete Liberation.

Footnotes

1 When asked whether he thought it a fact that Pa Dampa Sangye was a reincarnation of Bodhidharma, the founder of Zen, the Venerable Bardok Chusang Rimpoche sa id that he thought it quite possible, but ultimately whether or not he was, was not overly important. Venerable Bardok Rimpoche is himself recognized as the pre sent day reincarnation of Pa Dampa Sanggye.

2 Gorakhnath was the founder of Hatha-yoga. The heart of his system is to be found in the Six Khorlo of Naropa, which is kept a secret teaching in the Kagyu Sc hool. Gorakhnath's orginal asanas and mudras are still taught amongst initiates of the Nine Nath tradition.

3 There are some in America who are practicing Chöd outside of a recognized line o f transmission. This is psychically dangerous. To practice Chöd safely and beneficially, one must be intimately embraced by a school or "brotherhood" of others, w ho are all part of one's particular transmission. There are also different Chöd lineages, and one should practice always according to the oral instruction, encode d liturgy, and practice of one's own line agenot mix the lineage practices otherwise the practice may result in dire consequences, or even prove fatal.

4 H.P.Blavatsky, Raja-Yoga, or Occultism, Theosophy Company (India) Ltd., Bombay 1931).

5 Is Machig Labdrön here talking about what modern psychiatry calls the "messianic complex"?.

6 Machig Labdron, Phung-po gzan skyun rnam bshad gcod kyi don gsal byed.