Buddhist Heritage of Bodh Gayā: Pilgrimage and Religious Diaspora

Buddhist Heritage of Bodh Gayā: Pilgrimage and Religious Diaspora

Dr. Arvind Kumar Singh

Assistant Professor

School of Buddhist Studies and Civilization, Gautam Buddha University,

Greater Noida, Gautam Budh Nagar, UP-201308

Email: arvindbantu@yahoo.co.in, arvinds@gbu.ac.in

Abstract:

The present research paper is going to examine Buddhist heritage of Bodh Gayā and its transformation into a World Heritage site. Bodh Gayā as a place of cultural heritage and a Monument of “outstanding universal value” this inclusion has reinforced the ancient significance of Bodh Gayā as the place of Buddha's enlightenment and most sought after place for the followers of Buddhism. In this research work, I take this recent event as a framing device for my historical analysis that Bodh Gayā is constructed out of a

particular set of pilgrimage and religious diaspora. How do different groups attach meaning to Bodh Gayā's space and negotiate the multiple claims and memories embedded in place? How Bodh Gayā is socially constructed as a global site of memory and how do contests over its spatiality implicate divergent histories, narratives and events? In order to delineate the various historical and spatial meanings that

place holds for different groups I examine a set of interrelated transnational processes that are the focus of this paper: Brief History of Mahābodhi Temple at Bodh Gayā; Concept of pilgrimage in Buddhism; the influx of pilgrims from ancient time to present age; and Religious diaspora. Mahābodhi Temple Complex at Bodh Gayā is important global spaces of convergence where history,

memory, narratives and groups are entangled through UNESCO's universal claims. It is for these reasons that it is important to look beyond the universal abstraction and examine the ways in which spaces of global memory are laden with social and cultural meaning that is activated, reproduced and contested through a range of social practices. In my view, Bodh Gayā has created new meanings and forging new global public spheres across cultural, national and religious difference.

Key words:

Mahābodhi Temple, Pilgrimage, Religious Diaspora.

Introduction

Bodh Gayā is a place of international significance and its global relevance derives from its association with the Buddha, who attained enlightenment here over 2550 years ago. The Buddha mentions Bodh Gayā as one of the four places of Buddhist pilgrimage in the Mahāparinibbāna Sutta. King Aśoka was the first to build

a temple at this sacred spot. According to Asher[1], the attribution of the Mahābodhi Temple Complex to Aśoka and the events associated with the life of the Buddha serves to legitimize a kind of “mythic status” of Indian history to the monument, whereby the site becomes anchored in what is often

seen as “Buddhism‟s golden reign”, the universal significance of the Mahābodhi Temple Complex is also generated from its transnational validation as the cradle of Buddhism and the place which commemorates the memory of Buddha's enlightenment. The history of Buddhist influence at Bodh Gayā is documented by numerous

inscriptions, archaeological findings and travel accounts by pilgrims themselves. Foremost among these are the accounts of the Chinese pilgrims Faxian in the fifth century and Xuanzang in the seventh century. The latter describes the presence of a Ceylonese monastery named the Mahābodhi

Sangharama that was built by King Meghavana and housed over a thousand monks to the north gate of the Mahābodhi Temple. During this time, Bodh Gayā was part of the Magadha Empire, and the heart of a powerful Buddhist civilization that endured for many centuries. It was not until the fall of the [[Pāla

Dynasty]] and the growing influence of Muslim rule around the twelfth century that Buddhism became largely extinguished from its land of origins and many of these monuments and pilgrimage centers were destroyed or fell into ruin. Historically, the term Bodh Gayā came into use around the eighteenth century and was primarily adopted

to distinguish the sacred site from Gayā, a prominent centre of Hindu pilgrimage[2]. Prior to this, the place of Buddha's enlightenment had various designations including Uruvelā, Bodhimaṇḍa, Sambodhi, Vajrāsana and Mahābodhi.

Brief History of the Mahābodhi Temple at Bodh Gayā[3]

There is a need for an illustrated depiction of the chronology of the temple history, beginning with Emperor Aśoka‟s role at Bodh Gayā and ending with the role of Cunningham and his associates in the rebuilding of the temple during the time of British rule. The history of Bodh Gayā is documented by

many inscriptions and pilgrimage accounts. Foremost among these are the accounts of the Chinese pilgrims Faxian in the 5th century and Xuanzang in the 7th century. The area was at the heart of a Buddhist civilization for centuries until it was conquered by Turkish armies in the 13th century.

The first temple to be built at this sacred spot was by Aśoka. A portrayal of the Aśokan temple and other buildings built at Buddha Gayā around 256 BCE has been found in a bas-relief discovered at Bhārhūt Stūpa[4]. The present magnificent temple appears to have been built in the 2nd century CE over the remains of the Aśoka‟s temple. The age of the temple testified by the presence of a gold coin of King

Huviṣka amongst the Relics deposited in front of the throne, along with some punch-marked coins. The Indo-Scythian and Gupta inscriptions also record the construction of the great temple in the reign of Huviṣka.

According to inscription discovered at Bodh Gayā, a big Saṅgharāma was constructed by King Siri Meghavanna of Sri Lanka in 388 CE, a contemporary of Samudragupta (19). Some addition to the Mahābodhī temple was also made by Burmese in around 450 CE.

Almost three centuries after the visit of Xuanzang, no major repairs, no improvements appear to have been carried out at Bodh Gayā. It was only in 1010 CE that some minor repairs were reported to have been undertaken by Mahipāla of Pāla Dynasty. The first major restoration and renovation was carried out by Burmese in 1070 CE. The last Indian

Buddhist King to carry out repairs was Raja Aśokachalla of Sapadalaksa of Punjab.[5] Dharmaswamin found this place practically deserted because of the fear of Turuṣka soldiers in 1234 CE. He further narrates that the front of the Mahābodhī image is blocked with bricks and plastered and placed near it a substitute image.[6] A Burmese inscription of 1833 records major repairs done at the temple between

1295 and 1298. The Burmese undertook repair works at least thrice during the 14th and 15th centuries and thereafter Buddha Gayā was forgotten. Taking advantage of this situation a Hindu Mahant, Gosain Giri, established his Math in 1590, and the Buddhist shrine passed into the hand of non-Buddhists and the phase of sacrilege.

Bodh Gayā survived the pillage and plunder of the Muslim invasion which is evident from the biography of Dharmasvamin who visited India in 1234-36 CE. He says that „the place was deserted and only four monks were found staying in the Vihāra. One of them said, “It is not good! All have fled from fear of the

Turuṣka soldiery.”[7] Buchanan Hamilton found the Mahābodhī temple in utter ruins in 1811 and in 1861, Cunnigham found the Mahant and his followers indulging in all sorts of un-Buddhistic ceremonies in the main shrine. Burmese King Mindan Min, in 1875, obtained the permission for repair of Mahābodhī Mahāvihāra from

Government of India and Mahant. Later on due to the slow pace of repair work, Government of India deputed J. D. Beglar, Cunnigham, and Dr. Rajendra Lal Mitra to supervise the repair work in 1880. In 1883, Cunningham along with J. D. Beglar and Rajendralal Mitra painstakingly excavated the site and extensive renovation work was carried out to restore Bodh Gayā to its former glory.

Concept of Buddhist Pilgrimage

The idea of a pilgrimage came from the Buddha himself. Before He passed into Mahaparinibbāna, the Buddha advised pious disciples to visit four places that may be for their inspiration after He was gone which is well defined in the Mahaparinibbāna Sutta. The pious disciple should visit these places and look upon them with feelings of

reverence, reflecting on the particular event of the Buddha‟s life connected with each place. Although the forest hermitage where Buddha obtained enlightenment was not a significant site of pilgrimage during the Buddha‟s life, over the centuries, disciples of the Buddha began to visit the place and gradually transformed the site into a living center of Buddhist worship and sacred veneration. Linked to the

establishment of Buddhist pilgrimage at Bodh Gayā is the central monument, or Vihara, commonly referred to as the Mahābodhi Temple. Although there is a wide difference of opinion among modern scholars about the origins and date of the Mahābodhi Temple, early archaeological scholarship have traced the first commemorative shrine around the tree (the bodhighara) along with a protective stone railing and diamond

throne (Vajrasana), to the Mauryan emperor Aśoka in the third century BCE[8]. As part of Aśoka‟s campaign to promote the Buddha-Dharma in its homeland, the Emperor is often credited with helping legitimize the practice of pilgrimage and royal patronage to these sacred sites of Buddhist memory. The epigraphic evidence of Aśoka‟s

commemoration of a visit to the Buddha‟s birth place confirms the localization of pilgrimage practices connected with this event by the middle of the 3rd Century BCE. An early set of four sites (Lumbini, Bodh Gayā, Deer Park in Sarnath, and Kusinara) were later expanded to a list of eight sites (Savatthi, Sankasia, Rajagaha and Vesali) with their own narrative sites.[9] Aśoka‟s

inscriptions recording visits to Buddhist sites and addressed directly to the Buddhist Samgha deserve particular attention for illuminating early pilgrimage practices.[10] It is also an alternate explanation for the location of Aśoka‟s 16 minor rock edicts at places associated with pilgrimage (Yatras), fairs (Melas), gathering (samajas), and other local cultic activities.[11] Over the course

of many centuries, the Mahābodhi Temple Complex at Bodh Gayā was embellished and other key sites linked to the spiritual itinerary of its founder also became thriving religious centers of pan-Asian pilgrimage attracting Buddhist royalty, monastics, and lay devotees throughout the Indian subcontinent and beyond.[12] Therefore, not only is the temple complex inscribed on the basis of its unique architectural

and archaeological significance but also as a “living monument” that is an “exceptional testimony of the importance given to this place of pilgrimage by people from different countries through the passage of many centuries”.[13] Echoing earlier descriptions by Sir Edward Arnold and Dharmapala, the Mahābodhi Temple Complex at Bodh Gayā is also seen as the equivalent to Jerusalem

and Mecca as the pan-Asian center of one of the world‟s great religions. This is a place of active worship that reflects a “continuous tradition of philosophical thought and human values since the time of the Buddha”.[14] In other words, Bodh Gayā is a site that generates universal value only in relation to its Buddhist past and its continuity in terms of ritual activity today.

Religious Diaspora

Among the diverse streams of Buddhism that form the religious diaspora, Bodh Gayā is regarded as the navel of the earth: a place of pilgrimage and site of sacred reverence due to the significance of Buddha‟s enlightenment (Bodhi). Although transnationalism and the flow of people, ideas, and goods across

regional and nation-state boundaries are often regarded as a recent historical phenomenon, pilgrimage and religious movement have always been central to the practice of Buddhism.[15] Although the modern reinvention of Bodh Gayā as the place of Buddha‟s enlightenment began in the nineteenth and twentieth century, it is important to

highlight that the claims of international Buddhists today also reflect a much deeper historical pattern in the Indian subcontinent. Bodh Gayā‟s historical and sacred significance is supplemented by a long history of epigraphical and literary sources which bear testimony to the site‟s importance as a center of pilgrimage, art, learning and cultural interchange over the centuries.[16]

Since the time of Aśoka, there had been an institutional presence of Buddhist followers at this geographical center of faith. The establishment of Viharas and Saṃgharāmas that grew in the shadow of the Mahābodhi Temple was integral to the maintenance of the central shrine, the propagation of Buddhist teachings, and the economic

life of the surrounding villages.[17] In fact, many establishments were

also borne out of royal patronage as acts of merit and served to accommodate visiting pilgrims and guests coming from abroad. For example, the famous Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang describes staying at a huge monastery founded by King Meghavanna of Sri Lanka in the fourth century, which is believed to have existed in Bodh Gayā for over nine hundred years.[18] In the post-independence period, international interest in India‟s Buddhist geography grew substantially in the early fifties and culminated in the nation-wide celebration of the 2500th Buddha Jayanti, in 1956 to commemorate the birth, enlightenment and Parinirvana of the Buddha, was a historical landmark for the revival of

Buddhism at in India which helped to revitalize key inter-Asian links to the sacred place.[19] During this period, thousands of international

Buddhists, foreign dignitaries and local people converged on Bodh Gayā‟s§§ sacred space to honor the memory of the Buddha within its newfound national context.[20] As a large-scale nationwide program, this event helped to reinforce the idea that Bodh Gayā was the center of the Buddhist world within a wider international arena.[21]

Thailand and Southeast Asian Buddhism

In the wake of international success generated from the 2500th Buddha Jayanti celebrations, the King of Thailand, Bhumibol Adulyadej, was one of the first royal dignitaries in the post-independence era to acquire land in Bodh Gayā for the construction of a temple and rest house. The Royal Wat

Thai became the first Buddhist monastery and temple in Bodh Gayā to be built under the jurisdiction of a foreign head of state. To celebrate the growing cultural exchange program between India and Thailand, a golden Buddha image was also installed in the Royal Wat Thai on May 3rd 1967.The Royal Wat Thai in many ways served as a key benchmark for other national expressions of Buddhist architecture and

aesthetic design that followed in its aftermath. In a very few years, it has become the centre of epitome for pilgrims and initiated a surge in Thai Buddhist pilgrimage activities and a growing number of religious centres from Southeast Asia. Lastly, three other Southeast Asian

Buddhist centres that have acquired land in recent years that include: the Cambodian Buddhist Monastery (2003); the Thai Bodhi Kham (2004) and the Wat Thai Magadh Vipassanā Centre (2006)[22].

Burmese Vihara and Vipassanā

Another distinguished guest at Bodh Gayā during the Buddha Jayanti celebrations was the Prime Minister of Burma, U Nu[23] whose arrival provides another example of the continuing importance of pilgrimage and patronage by distinguished leaders of this neighboring country. During U Nu‟s visit to the place of enlightenment, he came into contact with

Acharya Anagarika Munindra who was invited to visit Burma for the purpose of receiving instruction in Vipassanā meditation from the famous Mahasi Sayadaw at Thathana Yeikta in Rangoon. Munindra visited Burma in early 1957 where he spent nearly ten years at the Mahasi Sayadaw‟s meditation center in

Rangoon. After his return from Rangoon, the Vipassanā meditation tradition had a tremendous effect on the Burmese monastery at Bodh Gayā and abroad. Ever since Munindra returned from Burma to Bodh Gayā, he was an active meditation teacher offering personal instruction at both the Burmese Vihara

and the Samanvay Ashram [24]. Following in the footsteps of Munindra was Satya Narain Goenka, who was born in Burma in 1924 and received formal training in Vipassanā from teacher Sayagyi U Ba Khin (1899-1971) beginning in 1955[25]. After fourteen years of training, beginning in 1955, Goenka returned to India in 1969 and began leading ten-day Vipassanā meditation courses and camps throughout the country. In Bodh Gayā,

Goenka‟s first meditation camp took place at the Samanvay Ashram on August 4th 1970 and continued to offer several ten-day courses over the winter season at both the Ashram and the Burmese Vihara.

=

Mahābodhi Society of India=

Ever since the Mahābodhi Society Rest House was established in 1901, this Buddhist centre, with its ecumenical thrust, has been at the heart of pilgrimage activities at Bodh Gayā. The building

itself reflects the British colonial architecture at the turn of the twentieth century with its covered verandah and arched entrance ways.[26] The successor to Dharmapala was Devapriya Valisingh who was instrumental in the formation of the Bodh Gayā Temple Act (1949), the demands for a separate Bodh Gayā

Temple Advisory Board, and the success of the 2500th Buddha Jayanti celebrations. Over the years Mahābodhi Society served as a centre of learning and culture through the propagation of Buddhist activities, seminars, symposiums and literature. For over one hundred years, the Mahābodhi

Society has been active throughout the Indian subcontinent as an ecumenical and transnational organization rather than a distinctly Sinhalese Buddhist institution. This is part of the reason why it has remained a centre of power and influence throughout the twentieth century.

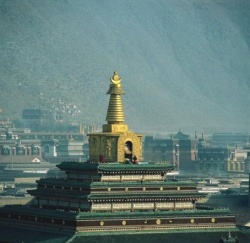

Tibetan Refugees and Himalayan Buddhists

In 1956, the 14th Dalai Lama, Tenzin Gyatso visited here despite mounting pressure from China.[27] In the company of the Panchen Lama and the Maharaja of Sikkim, the Tibetan leaders proceeded on pilgrimage to a number of Buddhist sites including Bodh Gayā on December 27, 1956. A public ceremony was held under the Bodhi tree in which the two respected teachers delivered sermons and

conducted pujas to a large audience. At the age of twenty one this was the Dalai Lama‟s first visit to Bodh Gayā but certainly not the last. As Toni Huber recently examined in The Holy Land Reborn, Tibetans have long maintained a ritual relationship with India, particularly by way of pilgrimage. Since the plight of the

14th Dalai Lama in 1959, more than 150,000 Tibetan refugees have fled to India over the last fifty years and the impact of this refugee community on Bodh Gayā has been tremendous.[28] Since 1959, the influence of the Tibetan refugees and Himalayan Buddhist groups has been immense, but the earliest Tibetan Buddhist gompa at Bodh Gayā predates the exiled community some

three decades earlier. In 1934 a small Tibetan Temple from the Gelug sect was constructed to the east of the Mahābodhi Society under the patronage of famous Lama Kanpo-Ngawang Samten of Ladakh. The first major ceremony involving a large religious assemblage of Tibetan

devotees was the Kalachakra empowerment initiation held in December 1974 and after that the Kalachakra initiation has become an important ritual medium for the public revitalization of Tibetan culture and religion in exile. Bodh Gayā has become “a meeting place for the diaspora

community - a place where they can gather socially, reunite with Tibetans who have recently fled their homeland, receive teachings from their religious leaders, build monasteries and begin to construct a new cultural and religious identity outside Tibet”.[29]

Japanese Buddhism

From the early seventies to the early nineties, the Japanese, like the Tibetans, had a tremendous impact on the development of international Buddhism at Bodh Gayā. Japanese have long maintained a close relationship

with the Mahābodhi Society ever since Dharmapala began his crusade to reclaim the Mahābodhi Temple for the world Buddhist community. In the post-independence era, the first royal Japanese guests to visit Bodh Gayā were the Crown Prince Akihito and the Crown Princess

Michiko, who arrived by charter plane at the Gayā airport on December 5, 1960. According to Ahir,[30] this historic day was the biggest welcome ever given to a foreign dignitary; upwards of 50,000 people had allegedly attended. Five years later, in October 1965, a large Japanese stone Pagoda was constructed in front

of the Royal Wat Thai by the International Buddhist Brotherhood Association (IBBA) or Kokusai Bukkyo Koryu Kyokai, an independent organization founded by the various Buddhist sects in Japan[31]. On

February 13, 1983 the Daijokyo Buddhist Temple was built and announced that the Daijokyo Sect had future plans to construct an 80 feet high image of Lord Buddha, a rest house for the benefit of pilgrims, a vocational training centre and an agricultural training program for the social welfare

of the local people. The Japanese Temple and Buddha Statue became a major tourist attraction at Bodh Gayā alongside a burgeoning number of Mahāyāna monasteries and temples that have certainly redefined the landscape as the navel of the earth and a major centre of world Buddhism.

East Asian Mahāyāna Buddhism

Although the Japanese have been very influential in terms of Buddhist development at Bodh Gayā, a number of prominent Mahāyāna Buddhist institutions from East Asia have also contributed to the

globalization of Bodh Gayā‟s landscape. A Vietnamese Buddhist Temple and Rest House named Viet Nam Phat Quoc Tu established in 1993 while another one named Vien Giac Institute was also established at Bodh Gayā in 2002 belongs to the Lin Tzi Zen tradition but practices pure land Buddhism. There is an old Chinese

Temple and the World Chongwa Buddhist Sangha of Taiwan that also built a temple and rest house. Linked to the transnational networks of East Asian Mahāyāna Buddhism at Bodh Gayā was the first international gathering of Buddhist nuns, held in February 1987. According to Thubten Chodron, this

special occasion was the first time in approximately 800 years that a Bhikshuni Sangha (a community of fully-ordained nuns), in India performed the Bhikshuni posadha, the nuns bimonthly purification and restoration of vows.‟ Although a lineage of fully ordained women had been kept alive in China,

Taiwan, Korea, and Vietnam, this was the first time, after many centuries, that a Bhikshuni posadha had been done in the land where the Buddha's teachings originated. In addition to reviving the Bhikshuni Sangha the special occasion was also the founding meeting of Sakyadhita, a worldwide Buddhist

women‟s organization which means “Daughters of the Buddha.” Lastly, in the early nineties, there have also been a growing number of Korean Buddhist institutions at Bodh Gayā. One of these centres is the Korean Buddhist Hokooksa Temple. Another active South Korean organization is known as the Sujata

Academy promoting education. Finally, there is one additional centre with prominent East Asian and Mahāyāna connections entitled the Asian Buddhist Cultural Centre founded by a Ladakhi monk known as Venerable Ananda.

Indian Buddhism

Al

though the general pattern of Buddhist development at Bodh Gayā reflects the global networks of transnational Buddhism but there are some Indian Buddhist groups with Theravada roots that have emerged since the post-independence period. A central Indian monastic organization named All Indian Bhikkhu Sangha

(AIBS) at Bodh Gayā was founded under the leadership of Jagadish Kashyap in July 1970. Jagdish Kashyap was an educated middle class Bihari who was ordained as Buddhist in Ceylon in 1934.[32] Noted for being a great scholar, he was involved in the early transcription of Pali and became the founder of the

Nava Nalanda Mahavihar. Unlike Jagdish Kashyap, almost all the members from the governing body came from the ethno-Buddhist background of the Barua and Chakma Buddhists of Bengal and Assam (Ahir 1998: 99). However, in the last few decades, the membership demographic of the AIBS shifted significantly and now

reflects the growing presence of Dalit Maharastran Buddhists or New Buddhist from the Ambedkar tradition. Lastly, in addition to the AIBS, four other Indian Buddhist institutions have settled in Bodh Gayā in recent years: the Buddhist Pilgrimage and Cultural Centre of Bangladesh (1992); the

Vajra Bodhi Society (1994) Chakma Buddhist Temple (1998) and Dhamma Chakra Mission (2000).

In the light of above discussion, I can say that all the above mentioned institutions and temples of foreign countries that I have developed in and around Bodh Gayā are playing a very im;ortant role in

turning this place into a centre of international pilgrimage and also imparting education and other social works in the area, improving the economic condition of local people. Here one can that Bodh Gayā is known to the whole world due to its heterogeneity and diversity across national, sectarian and

cultural lines. Initially, the growth and expansion of transnational networks from the religious diaspora came to reflect the national aspirations of Jawaharlal Nehru who helped to recreate an international religious conclave of Buddhist monasteries, temples and/or guest houses. However, by the

late seventies and eighties, Theravāda influence at Bodh Gayā was eclipsed by the growing institutional presence of Mahāyāna Buddhism and the expanding Vajrayāna networks within the Tibetan refugee community. In light of the proliferation of institutions, the Bodh Gayā Temple Advisory Board met on

April 4, 1986 and decided that all Buddhist countries should be directed to maintain a representative “national character” and that land should not be allotted indiscriminately. However, from the late eighties onwards, national articulations of Buddhism provided a difficult container for the complex transnational networks of the religious diaspora.

Conclusion

The Mahābodhi Temple at Bodh Gayā is a living monument where people from all over the world even today throng to offer their reverential prayers to the Buddha. It is an icon of continuity in the present fast

moving modern world. In my opinion, expanding the definition of World Heritage beyond the monumental to the living is an important step in transcending the physical orientation due to which it becomes an integral factor that distinguishes the Mahābodhi Temple Complex from other sites which are deemed “dead monuments” or

cultural artifacts that reflect the preservationist desire and fossilization of past landscapes. Approaching the Mahābodhi Temple Complex as a living monument does not necessarily mean that the conservation message is lost either, but rather it foregrounds the ritual embodiment of Buddhist faith and

the importance of those living traditions such as pilgrimage that can never be safeguarded. Although Bodh Gayā is now a cultural heritage site of “outstanding universal value to humanity” and is not only a revered site of Buddhist memory but it also a place that serves overlapping religious interests and pilgrimage

that are an integral part of a living religious monument. Taking the above said points into account, I have no hesitation in declaring it as “the Centre of World Buddhism” in true sense.

References

1. Ahir D. C., Buddhist shrines in India, B. R. Publishing Corporation, Delhi: 1986.

2. Ahir D. C., Buddha Gayā through the Ages. Sri Satguru, Delhi: 1994.

3. Ahir, D. C., The Pioneers of Buddhist Revival in India. Delhi, Sri Satguru Publications, Delhi: 1989.

4. Asher, F. M., Bodh Gayā: Monumental Legacy, Oxford University Press, New Delhi: 2008.

5. Bapat P. V., 2500 Years of Buddhism. Publication Division, Delhi: 1956.

6. Barua B. M., Gayā and Buddha Gayā. Indian Research Institute, Calcutta: 1931 & 1934.

7. Beal S., Si-Yu-Ki Buddhist records of the western world. Low Price, Delhi, Reprint: 2008.

8. Dalai Lama, Freedom in Exile: The Autobiography of the Dalai Lama of Tibet, London: Abacus: 1991.

9. Dhammika, S., Navel of the Earth: The History and Significance of Bodh Gayā, Buddha Dhamma Mandala Society, Singapore: 1996.

10. Doyle, T. N., Bodh Gayā: Journeys to the Diamond Throne and the Feet of Gayāsur, Cambridge, Harvard University: 1997.

11. Fausboull, V., ed., The Jatakas, vols. 7. Trubner, Pali Text Society, London: 1877–1897.

12. Feer, M. L., ed., The Samyutta Nikaya, vol. 5, Pali Text Society, London: 1884–1898.

13. Guha-Thakurta, T., Monuments, Objects, Histories: Institutions of Art in Colonial and Postcolonial India. New York, Columbia University Press: 2004.

14. Heine, S. and Prebish, C., Buddhism in the Modern World: Adaptations of an Ancient Tradition, Oxford, Oxford University Press: 2003.

15. http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1056.

16. Mitra D., Buddhist Monuments. Sahitya Sansad, Calcutta: 1971.

17. Morris R, Hardy E., ed., The Anguttara Nikaya, vol IV. Pali Text Society, London: 1885–1900.

18. Oldenberg H., ed., The Vinaya Pitaka, vols. 5, Williams and Norgate, Pali Text Society, London: 1879-1883.

19. Rhys Davids, T. W., Rhys Davids, C. A. F., eds., The Digha Nikaya (The Dialogues of the Buddha), vols. 3, Pali Text Society, London: 1899, 1910 & 1957.

20. Roerich, G., & Altekar A. S., Biography of Dharmasvamin. K. P. Jayaswal Research Institute, Patna: 1959.

21. Sarao, K. T. S., Urban Centres and Urbanization: As Reflected in the Pāli Vinaya and Sutta Pitakas. Munshiram Manoharlal, Delhi

22. Singh, Arvind Kumar, Bodha Gayā in Encyclopedia of Indian Religions, ed. Sharma, Arvind, Springer, Netherlands (Under Publication): 2013..

23. Trenckner V, & Chalmers R., eds., The Majjhima Nikaya. Pali Text Society, London: 1888–1896.

24. Trevithick, A., The Revival of Buddhist Pilgrimage at Bodh Gayā (1811 1949): Anagarika Dharmapala and the Mahābodhi Temple, Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass: 2006.

Footnotes

- ↑ Asher, 2008: 80.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Singh, 2008.

- ↑ Fusboull:

- ↑ Roerich, and Altekar: 1959.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Mitra:

- ↑ Guha-Thakurta 2004; Asher 2008.

- ↑ Neelis, 2011: 70.

- ↑ Ibid.: 88.

- ↑ Ibid.: 188n 10.

- ↑ Doyle 1997.

- ↑ (http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1056)

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ This version of the Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra was reproduced from Dhammika (1996: 3).

- ↑ For more on Bodh Gayā and earlier narrative accounts of pilgrimage traffic since the time of the Aśoka see Dhammika (1996) Navel of the Earth” The History and Significance of Bodh Gayā. Also, Aitken (1995) Meeting the Buddha: On Pilgrimage in Buddhist India.

- ↑ The Sanskrit and Pali term Viharas and Saṃghārāma refer to a place of worship or a Buddhist monastery. According to Dhammika (1996: 47-49), these dwellings were likely seasonal abodes for wandering monks during the rainy season but over the centuries they became important centres of royal patronage and religious practice.

- ↑ According to Dhammika's (1996: 25) analysis, during the early decades of the 4th Century the Mahabodhi monastery was established in Bodh Gayā. The monastery is linked to the younger brother of King Meghavanna of Sri Lanka (304-332 CE), a monk of royal birth, who embarked on pilgrimage to India and complained about ill treatment by other monasteries en route to Bodh Gayā. In light of these events he sent an envoy to the King Samudragupta of India with a gift of jewels and seeking permission to build monasteries at all the sacred places for the convenience of Buddhist pilgrims. Furthermore, according to Xuanzang’s account of the Mahabodhi Monastery, at the front entrance was inscribed a copper plate where Meghavanna proclaimed the establishment‟s policy of hospitality: “To help all without distinction is the highest teachings of all the Buddhas, to exercise mercy as occasion offers is the illustrious doctrine of former saints” (Dhammika 26)

- ↑ Although there is little consensus among historians and Buddhist schools around the specific date of the birth, enlightenment and Parinirvāṇa of the Buddha, among Theravāda Buddhists this date is often associated with vesak, a full moon which falls in late April or May.

- ↑ Doyle 1997.

- ↑ Some of the nationwide activities included: physical improvements made at Buddhist sites, the publication of dozens of government-sponsored books and pamphlets on Buddhism and Buddhist Places (such as the book, entitled 2500 Years of Buddhism, produced by the Publications division of the Government of India Information and Broadcasting Ministry), the broadcasting of numerous features, talks, and dramas about Buddhism by All India Radio, the convening of an International Buddhist Conference, the erection of the Buddha Jayanti Monument in Delhi, the issuing of a commemorative stamp, the making of a government-sponsored film on the Life of Buddha, publication of the complete Pāli Tripiṭaka in several Indian languages, and the organization of thousands of Buddha Jayanti cultural events and cultural programs on the life and teachings of the Buddha. For more on the Buddha Jayanti events see Doyle 1997: 204.

- ↑ Thai Bodhi Kham was first established in 1979 when land was purchased in village Miya Bigha (Siddhartha Nagar) by the late Dr. Dhamma Wansa. However, it was not until 2004 that the organization was formally registered. Since 1979 the Thai Bodhi Kham has been run by Buddhist disciples of Dr. Dhamma Wansa from the Indian State of Arunachal Pradesh.

- ↑ U Nu was a devout Buddhist and popular political leader of Burma. He had the Kaba Aye (World Peace) pagoda and the Mahāpasāna Guha (Great Cave) built in 1952 in preparation for the Sixth Buddhist Council that he convened and hosted in 1954-1956 as prime minister. The council concluded in 1956 which coincided with the 2500th Buddha Jayanti celebrations. On August 29, 1961 U Nu was also instrumental in declaring Buddhism as the official state religion in the Parliament. However, this constitutional amendment became largely ineffective when Ne Win took over power in March 1962.

- ↑ The Samanvay Ashram was founded in 1954 by Dwarko Sundrani and Vinoba Bhave. It is a charitable trust that works towards the betterment of the scheduled castes and scheduled tribes in the Bodh Gayā region. The ashram is based on Gandhian values and is a centre for research and training in education and development.

- ↑ Goenka is a central figure in the global diffusion of the Vipassanā movement and has taught tens of thousands of people throughout the world. The Vipassanā technique that S.N. Goenka teaches represents a tradition that is believed to be traced back to the Buddha. His approach is entirely non-sectarian and regards the Dhamma – not Buddhism – as the way to liberation. The main Dhammagiri Institute/Vipassanā International Academy was founded by Satya Narain Goenka in 1974 in Igatpuri near Bombay.

- ↑ Asher 2008.

- ↑ In 1956, the Maharaj of Sikkim arrived in Lhasa with a letter from the President of the Mahabodhi Society requesting the participation of the Dalai Lama to attend the 2500th Budha Jayanti. In Dalai Lama‟s (1991: 123) biography Freedom in Exile he writes: “I was ecstatic. For us Tibetans, India is Aryabhumi, the Land of the Holy. All my life I had longed to make a pilgrimage there: it was the place that I most wanted to visit.” The Dalai Lama departed Lhasa at the end of November in 1956 with a small entourage including the Panchen Lama and Lobsang Samten. They traveled to Gangtok in Sikkim and later to New Delhi where he met with Prime Minister Nehru and the President of India, Rajendra Prasad.

- ↑ In exile, the 14th Dalai Lama returned to Bodh Gayā in the winter of 1960. There he met a large deputation of Tibetan refugees undertaking pilgrimage. In his own words (1991: 172): “A very moving moment followed when their leaders came to me and pledged their lives in the continuing struggle for a free Tibet. After that, for the first time in this life, I ordained a group of 162 young Tibetan novices as bhiksus. I felt greatly privileged to be able to do this at the Tibetan monastery which stands within sight of the Mahabodhi Temple.”

- ↑ Doyle 351.

- ↑ Ahir, 1992: 138.

- ↑ In a pamphlet produced by the IBBA organization it states four main objectives in relation to Bodh Gayā: a) [[To build]] a Japanese Temple and an International Buddhist House at the sacred place of Bodh Gayā where Lord Buddha attained enlightenment. b) To provide facilities for Japanese Buddhists to come and learn the teaching of Lord Buddha to strengthen their belief in Buddhism. c) To provide facilities for international understanding and also for all people to exchange Japan-India's cultural ideas and also to give facilities to world Buddhists to have discourses to enlighten themselves. d) To work for the world peace and human happiness by studying and sincerely following the teachings of the Buddha.

- ↑ Ahir 1989: 89-100.

Source

By Dr. Arvind Kumar Singh