Kathâ-vatthu

I HAVE first to notice a few points as to the history of the Milinda book which have either come to light since the former Introduction was written, or which I then omitted to notice.

Mr. Bunyiu Nanjio in his Catalogue of Chinese Buddhist Books 1 mentions a Chinese book called Nâ-sien Pikhiu Kin (that is 'The Book of the Bhikshu Nâgasena' Sûtra)

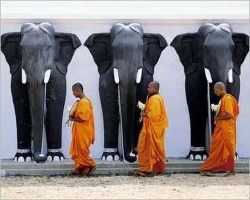

2. I have been so fortunate as to receive detailed information about this book both from Dr. Serge d'Oldenbourg in St. Petersburg and from M. Sylvain Lévi in Paris. Professor Serge d'Oldenbourg forwarded to me, in the spring of 1892, a translation into English (which he himself had been kind enough to make) from a translation into Russian by Mr. Ivanovsky, of the Chinese Introduction, and of various episodes in the Chinese which seemed to differ from the Pâli. This very valuable aid to the interpretation of the Milinda, which the unselfish courtesy of these two Russian scholars intended thus to place at my disposal, was most unfortunately lost in the post; and I have only been able to gather from a personal interview with Professor Oldenbourg that the Introduction was a sort of Gâtaka story in which the Buddha appeared as a white elephant 3.

By a curious coincidence this regrettable loss has been

since made good by the work of two French scholars. Mons. Sylvain Lévi forwarded to the Ninth International Congress of Orientalists, held in London in the autumn of 1892, a careful study on the subject by M. Edouard Specht, preceded by an introductory essay by himself.

It appears from this paper, which excited much interest when it was read, that there are, not one, but two separate and distinct works extant in China under the name of Nâ-sien Pikhiu Kin, the one inserted in the Korean collection made in that country in 1010 A.D., and the other printed in the collection of Buddhist books published under the Sung in 1239. Neither the date nor the author of either version seems to be known, but Mr. Bunyiu Nanjio states of his work, which is probably one of the two, that it was composed between 317 and 420 A.D. 1 The Korean book gives much less of the matter contained in our books II and III than the later work in the Sung collection, the former containing only 13,752 characters while the latter has 22,657. In the matter of the order of the questions also the later of the two Chinese books follows much more closely the order found in the present translation than does the work found in the Korean collection.

This paper has since been published in the Proceedings of the Congress 2, and it gives translations of several episodes on questions in which the Chinese is said to throw light on the Pâli. Both M. Specht and M. Sylvain Lévi seem to think that the two Chinese books were translations of older recensions of the work than the one preserved in Pâli. This argument does not seem to me, as at present advised, at all certain. It by no means follows that a shorter recension, merely because it is shorter, must necessarily be older than a longer one. It is quite as possible that the longer one gave rise to the shorter ones.

[paragraph continues] The story of a discussion between Nâgasena and Milinda is no doubt, if the arguments in the Introduction to Part I are of any avail, an historical romance with an ethical tendency. In constant repetition, after it had become popular, it is precisely those parts which do not appeal so easily to the popular ear (because they deal, not with ordinary puzzles, but with dilemmas or with the higher mysteries of Arahatship), that would be naturally omitted. I do not go so far as to say that it must have been so. But I venture to think that for a critical judgment as to the comparative dates of the three works on the same subject, now known to exist, we must wait till translations of the whole of the two independent Chinese versions are before us. And further that the arguments must then turn on quite other considerations than the very ambiguous conclusions to be drawn merely from the length or shortness of the different treatment in each case. It is very much to be hoped therefore that M. Specht will soon give us complete versions of the two Chinese works in question.

At present it can only be said that we have a very pretty puzzle propounded to us, a puzzle much more difficult to solve than those which king Milinda put to Nâgasena the sage. If the shorter version (or rather paraphrase, for it does not seem to be a version at all in our modern sense)--that from the Korea--be really the original, how comes it that the other Chinese book, included in a collection made two centuries later, should happen to differ from it in the precise parts in which it, the supposed original, differs from the Pâli? Surely the only probable hypothesis would be that of the Chinese books, both working on the same original, the later is more exact than the earlier: and that we simply have here one more instance of an already well-known characteristic of Chinese reproductions of Indian books--namely, that the later version is more accurate than the older one. The later a Chinese 'translation' the better, in the few cases where comparison is possible, it has proved to be (that is, the nearer to our idea of what a translation should be);

and Tibetan versions are better, as a rule, than the best of the Chinese.

Since the publication of this very interesting paper, M. Sylvain Lévi has had the great kindness to send me an advance proof of a more complete paper, to be published in Paris, in which M. Specht and himself have made a detailed analysis of the three versions, setting out over against the English translation of each question (as contained in the first volume of the present work) the translations of it as they appear in each of the Chinese versions. I have not been able by a study of this analysis to add anything to the admirable summary of the conclusions as to the relations of these two books to one another and to the Pâli which are given by M. Specht in his article in the Proceedings of the Ninth Congress. The later version is throughout much nearer to the Pâli; but neither of the two give more than a small portion of it, the earlier does not seem to go much further than our Volume I, page 99 (just where the Pâli has the remark, 'Here end the questions of king Milinda'), and the later, though it goes beyond this point, apparently stops at Volume I, page 114.

These details are of importance for the decision of the critical question of the history of the Milinda. The book starts with an elaborate and very skilful introduction, giving first an account of the way in which Nâgasena and Milinda had met in a previous birth, then the life history, in order, of each of them in this birth, then the account of how they met. Throughout the whole story the attention is constantly directed to the very great ability of the two disputants, and to the fact that they had been specially prepared through their whole existence for this great encounter, which was to be of the first importance for religion and for the world. This introductory story occupies in my translation thirty-nine pages. Is it likely that so stately an entrance hall should have really been built to lead only into one or two small rooms?--to two chapters occupying only sixty pages more? Is it not more probable that the original architect had a better sense of proportion? As an Introduction to the book as we have it in these

volumes the story told in those thirty-nine pages is very much in place; as an Introduction to the first two chapters only, or to the first two and a portion of the third, it is quite incongruous. And accordingly we find in the very beginning of the Introduction a kind of table of contents in which the shape of the whole book, as we have it here, is foreshadowed in detail, and in due proportion. This will have to be taken into account when, with full translations of the two Chinese books before us, we shall have to consider whether they are really copies of the original statue, or whether they are interesting fragments.

I ought not to close this reference to the labours of MM. Lévi and Specht without calling attention to a slip of the pen in one expression used by M. Sylvain Lévi regarding the Milinda 1. He says, 'La science ne connaissait jusqu'ici de cet ouvrage qu'un texte écrit en Pâli et incorporé dans le canon Singhalais?' Now there is, accurately speaking, no such thing as a Sinhalese canon of the Buddhist Scriptures, any more than there is a French or an English canon of the Christian Scriptures. The canon of the three Pitakas, settled in the valley of the Ganges (probably at Patna in the time of Asoka), has been adhered to, it is true, in Ceylon, Burma, and Siam. But it cannot properly be called either a Ceylonese or a Burmese or a Siamese canon. In that canon the Milinda was never incorporated. And not only so, but the expression used clearly implies that there is some other canon. Now there has never been any other canon of the Buddhist Scriptures besides this one of the three Pitakas. Many Buddhist books, not incorporated in the canon, have been composed in different languages--Pâli, Sanskrit, Chinese, Tibetan, Japanese, Sinhalese, Burmese, Siamese, &c.--but no new canon, in the European meaning of the phrase, has ever been formed.

One meets occasionally, no doubt, in European books on Buddhism allusions or references to a later canon

supposed to have been settled at the Council of Kanishka. The, blunder originated, I believe, with Mr. Beal. But in the only account of that Council which we possess, that of Yuan Thsang 1, there is no mention at all of any new canon having been settled. The account is long and detailed. An occurrence of so extreme an importance would scarcely have escaped the notice of the Chinese writer. But throughout the account the canonicity of the three Pitakas is simply taken for granted. The members of the Council were chosen exclusively from those who knew the three Pitakas, and the work they performed was the composition of three books--the Upadesa, the Vinaya Vibhâshâ, and the Abhidharma Vibhâshâ. The words which follow in the Chinese have been differently interpreted by the European translators. Julien says:

'They (the members of the Council) thoroughly explained the three Pitakas, and thus placed them above all the books of antiquity 2.'

Beal, on the other hand, renders:

'Which (namely, which three books) thoroughly explained the three Pitakas. There was no work of antiquity to be compared with (placed above) their productions 3.'

It is immaterial which version best conveys the meaning of the original. They both clearly show that, in the view of Yuan Thsang, the Council of Kanishka did not establish any new canon. Since that time the rulers of China, Japan, and Tibet have from time to time published collections of Buddhist books. But none of these collections even purports to be a canon of the Scriptures. They contain works of very various, and some quite modern, ages and authors: and can no more be regarded as a canon of the Buddhist Scriptures than Migne's voluminous collection of Christian books can be called a new canon of the Christian Scriptures.

This was already pointed out in my little manual, 'Buddhism,' published in 1877, and it is a pity that references in subsequent books to a supposed canon settled at Kanishka's Council have still perpetuated the blunder. M. Sylvain Lévi, for whose genius and scholarship I have the profoundest respect, does not actually say that there was such a canon; but his words must lead readers, ignorant of the facts, to imply that there was one.

I have also to add that M. Barth has called attention 1 to the fact that M. Sylvain Lévi has added another service to those already mentioned as rendered by him to the interpretation of the Milinda, by a discussion of the reference to our book in the Abhidharma-kosa-vyâkhyâ, referred to in my previous Introduction, p. xxvi. This discussion was published in a periodical I have not seen 2. But it seems that M. Lévi, with the help of two Chinese translations, has been able to show that the citation is not only in the commentary, but also in the text, of Vasubandhu's work. M. Léon Feer has been kind enough to send me the actual words of the reference, and they will be found published in the 'Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society' for 1991, p. 476.

Professor Serge d'Oldenbourg has also been good enough to point out to me that the two Cambridge MSS. of Kshemendra's Bodhisattvâvadâna-kalpalatâ read Milinda (not Millinda as given by Râjendra Lâl Mitra 3) as the name of the king referred to in the 57th Avadâna, the Stûpâvadâna. I had not noticed this reference to the character in our historical romance. It comes in quite incidentally, the Buddha prophesying to Indra that a king Milinda would erect a stûpa at Pâtaligrâma. There is no allusion to our book, and the passage is only interesting as showing that the memory of king Milinda still survived in India at the time when Kshemendra wrote in the eleventh century A.D.

Another reference to one of the characters in the Milinda

which has Come to notice since the publication of part i, is in the closing words of the Attha-Sâlinî-Atthayoganâ (a tikâ on Buddhaghosa's first work, his commentary on the Dhamma Sangani), which was written in Siam after the twelfth century by Ñânakitti, and edited in 1890 at Galle, by Paññâsekhara Unnânsê. On page 265 we read:

Vattaniya-senâsane ti Viñghâtaviyam Vattaniya-senâsane. Tena vuttam Mahâvamse:

Assagutta-mahâthero pabhinna-Patisambhido

Satthi-bhikkhû sahassâni Viñghattaviyam âdiya

Vattaniya-senâsanâ nabhasâ tattha-m-otarîti.

'The words Vattaniya-senâsane mean, "in the Vattaniya Hermitage in the Vindhya Desert." Therefore it is said in the Mahâvamsa:

'"The great Thera Assagutta, who knew so well the Patisambhidâ, bringing sixty thousand brethren from the Vattaniya Hermitage in the Vindhya Desert through the sky, descended there."'

This quotation is very interesting. It follows that in the original text of the Attha Sâlinî there is something about the Vattaniya Hermitage. And also that the author of this Tîkâ must have had before him some text of our Mahâvamsa differing from ours, or perhaps some other Mahâvamsa. For the lines quoted do not occur in our text. The nearest approach to them is one line in the description of the assembly that came together at the consecration of the Mahâ Thûpa at Anurâdhapura in the year 157 B.C. It runs 1:

Viñghâtavi-Vattaniya-senasânâ 2 tu Uttaro

Thero, satthi-sahassâni bhikkhû âdâya âgamâ.

'The thera Uttara came up bringing with him sixty thousand Bhikshus from the Vattaniya Hermitage not Uttania Temple as Turnour translates] in the Vindhya Desert.'

The resemblance of the passages is striking. But all

that can be concluded is that the author of our Mahâvamsa, Mahânâma, who wrote in the middle of the fifth century, knew of the Vattaniya Hermitage; and that the author of the text quoted by Ñânakitti (in a passage probably describing the same event) mentions an Assagutta as having come to the festival from his hermitage at Vattaniya.

Both these references are entirely legendary. In order to magnify the importance of the great festival held in Ceylon on the occasion referred to, it is related that certain famous members of the Buddhist order came, attended by many followers, through the sky, to take part in the ceremony. A comparison of this list with the previous list, also given in the Mahâvamsa 1, of the missionaries sent out nearly a hundred years before, by Asoka, will show that the names in the second list are in great part an echo of those in the first. But in selecting well-known names, Mahânâma in his second, fabulous, list has, according to the published text, also included that of the Vattaniya Hermitage, and, according to the new verse in the other text, has associated with that place the name of Assagutta, not found elsewhere except in the Milinda. In that book the residence of Assagutta is not specified--it is his friend Rohana who lives at the Vattaniya, and the locality of the Vattaniya is not specified--it would seem from the statement at I, 25 (part i, p. 20 of this translation) that it was a day's journey from 'the Guarded Slope,' that is, in the Himâlayas. But geographical allusions are apt to be misleading when the talk is of Bhikshus who could fly through the air. And it seems the most probable explanation that the authors of these verses, in adopting these names, had the Milinda story in their mind.

[Turnour's reading of the name as Uttara, and not Assagutta, is confirmed by the Dîpavamsa, chap. XIX, verses 4-6, where all the fourteen names of the visitors from India are given (without any details as to the districts whence they came), and the corresponding name is also Uttara there.]

The above sets out all the new information I have been able to glean about the Milinda since the publication of the Introduction to the first volume of this translation. I had hoped in this Introduction to discuss the doctrines, as apart from the historical and geographical allusions, of our author--comparing his standpoint with that of the earliest Buddhists, set out in the four great Nikâyas, with that of later books contained in the Pitakas, and with that of still later works not included in the canon at all. I have to express my regret that a long and serious illness, culminating in a serious accident that was very nearly a fatal one, has deprived me altogether of the power of work, and not only prevented me from carrying out this perhaps too ambitious design, but has so long delayed the writing of this Introduction.

Only one of the preliminary habours to the intended Introduction was completed. I read through the Kathâ Vatthu, which has not yet been edited, with a view of ascertaining whether, at the time when that book was written, that is, in the time of Asoka, the kind of questions agitating the Buddhist community bore any relation to the kind of questions discussed by the: author of our Milinda. As is well known, the Kathâ Vatthu sets out a number of points on which the orthodox school, that of the Thera-vâdins, differed in Asoka's time from the other seventeen schools (afterwards called collectively the Hînayâna) which had sprung up among the Buddhists between the time of the Buddha and that of Asoka. I published in the 'Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society' for 1892 a statement, both in the original Pâli and in English, of all the points thus discussed by the author of the Kathâ Vatthu, Moggali-putta Tissa Thera, giving (from the commentary) the names of the various schools against whom, in each instance, his remarks were directed.

It is now possible to judge from this analysis of the questions proposed, what were the subjects on which differences obtained among the early Buddhists. There are a number of points raised in Tissa's discussions which are also discussed by the author of the Milinda. In every

p. xxi

instance the two authors agree in their views, Nâgasena in the Milinda always advocating the opinion which Tissa puts forward as that of the Thera-vâdins. This is especially the case with those points which Moggali-putta Tissa thinks of so much importance that he discusses them at much greater length than the others.

His first chapter, for instance, by far the longest in his book, is on the question whether, in the high and truest sense of the word, there can be said to be a 'soul' 1. It is precisely this question which forms also the subject of the very first discussion between Milinda and Nâgasena, the conversation leading up to the celebrated simile of the chariot by which Nâgasena apparently convinces Milinda of the truth of the orthodox Buddhist view that there is really no such thing as a 'soul' in the ordinary sense 2. On leaving the sage, the king returns to his palace, and the next day the officer who escorts Nâgasena there to renew the discussion, occupies the time to raise again the same question, and is answered by the simile of the musicians 3. Not content with these two expositions of this important doctrine, the author of the Milinda returns again soon afterwards to the same point, which he illustrates by the simile of the palace 4, and further on in the book he takes occasion to discuss and refute the commonly held opinion that there is a soul in inanimate things, such as water 5.

It cannot be doubted that the authors of the Kathâ Vatthu and the Milinda were perfectly justified in putting this crucial question in the very forefront of their discussion--just as the Buddha himself, as is well known, made it the subject of the very first discourse he addressed to his earliest converted followers, the Anatta-lakkhana Sutta, included both in the Vinaya and in the Anguttara Nikâya 6.

The history of ideas about the 'soul' has yet to be

written. But the outlines of it are pretty well established, and there is nothing to show that the Indian notions on the subject, apart perhaps from the subsidiary beliefs in Karma and transmigration, were materially different from those obtaining elsewhere. Already in prehistoric times the ancestors of the Indian peoples, whether Aryan by race or not, had come to believe, probably through the influence of dreams, in the existence inside each man of a subtle image of the man himself. This weird and intangible form left the body during sleep, and at death it continued in some way to live. It was a crude hypothesis found useful to explain the phenomena of dreams, of motion, and of life. And it was applied very indiscriminately to the allied phenomena in external things--the apparent life and motion, not only of animals, but also of plants and rivers, of winds and celestial bodies, being explained by the hypothesis of a soul within them.

The varying conditions and appearances of the external world gave rise to the various powers and qualities ascribed to these external souls, and hence to whole systems of polytheism and mythology. And just as the gods, which never had any existence except in the ideas of their worshippers, were born and grew and changed and passed away with those ideas, so also the hypothesis of internal souls had, no less in India than elsewhere, a continual change, a continual development--and this not only as to ideas on the nature and origin of the internal human souls, but as to their relation to the external souls or gods. And when speculation, which loved to busy itself with these mysterious and fanciful hypotheses, had learnt to conjecture a unity behind the variety of external spirits, the relation of men's souls to the one great first cause, to God, became the subject of endless discussions, of varying views invented to harmonise with varying preconceived conceptions.

When Buddhism arose these hypotheses as to 'souls,' internal and external, formed the basis of all the widely differing, and very living and earnest, religious and philosophical speculations in the valley of the Ganges, where there then obtained that marvellous freedom of thought

on all such subjects which has been throughout its history a distinguishing characteristic of the Indian people. Now there is one work, of more importance than any other in Buddhism, the collection of the Dialogues of Gotama the Buddha, brought together in the Dîgha and Magghima Nikâyas. It contains the views of the Buddha set out, as they appeared to his very earliest disciples, in a series of 185 conversational discourses, which will some day come to hold a place, in the history of human thought, akin to that held by the Dialogues of Plato. Is it a mere chance, or is it the actual result of the necessities of the case, that this question of 'souls' is put into the forefront of this collection, just as it is the point treated first and at the greatest length in the Kathâ Vatthu, and put first also in the Milinda?

The first of these 185 dialogues is the Brahmagâla Suttanta, the discourse called the Perfect Net, the net whose meshes are so fine that no folly of superstition, however subtle, can slip through--the clearing away of the rubbish before the foundations are laid for the new palace of good sense. In it are set out sixty-two varieties of existing hypotheses, and after each and all of them has been rejected, the doctrine of Arahatship is put forward as the right solution. The sixty-two heresies are as follows:

1-4. sassata-vâdâ. People who, either from meditation of three degrees, or fourthly through logic and reasoning, have come to believe that both the external world as a whole, and individual souls, are eternal.

5-8. ekakka-sassatikâ. People who, in four ways, hold that some souls are eternal, while others are not.

a. Those who hold that God is eternal, but not the individual souls.

b. Those who hold that all the gods are eternal, but not the individual souls.

c. Those who hold that certain illustrious gods are eternal, but not the human souls.

p. xxiv

d. Those who hold that while the bodily forms are not eternal, there is a subtle something, called Heart or Mind, or Consciousness, which is.

9-12. antântikâ. People who chop logic about finity and infinity.

a. Those who hold the world to be finite.

b. Those who hold it to be infinite.

c. Those who hold it to be both.

d. Those who hold it to be neither.

13-16. amara-vikkhepikâ. People who equivocate about virtue and vice--

a. From the fear that if they express a decided opinion grief at possible mistake will injure them.

b. That they may form attachments which will injure them.

c. That they may be unable to answer skilful disputants.

d. From dullness and stupidity.

17, 18. ADHIKKA-SAMUPPANIKÂ. People who think that the origin of things can be explained without a cause.

19-50. UDDHAMA-ÂGHATANIKÂ. People who believe in the future existence of human souls.

a. Sixteen different phases of the hypothesis of a conscious existence after death.

b. Eight different phases of the hypothesis of an unconscious existence after death.

c. Eight different phases of the hypothesis of an existence between consciousness and unconsciousness after death.

51-57. ukkheda-vâdâ. People who teach the doctrine that there is a soul, but that it will cease to exist on the death of the body here, or at the end of a next life, or of further lives in higher and ever higher states of being.

58-62. dittha-dhammika-nibbâna-vâdâ. People who hold that there is a soul, and that it can attain to perfect bliss in this present world, or in whatever world it happens to be--

p. xxv

a. By a full, complete, and perfect enjoyment of the five senses.

b. By an enquiring mental abstraction (the First Dhyâna).

c. By undisturbed mental bliss, untarnished by enquiry (the Second Dhyâna).

d. By mental peace, free alike from joy and pain and enquiry (the Third Dhyâna).

e. By this mental peace plus a sense of purity (the Fourth Dhyâna).

Professor Garbe, in his just published 'Sankhya Philosophie 1,' holds that the first persons attacked in this list are the followers of the Sânkhya. The double view of the Sassata-vâdâ is no doubt the basis of the Sânkhya system. But the system contains much more, and it would be safer to say that we have here a warning against the philosophical view which afterwards developed into the Sânkhya, or rather which became afterwards a fundamental part of the Sânkhya. The Vedânta, in either of its forms, is not, it will be noticed, referred to in any one of the sixty-two divisions; but philosophical views forming part of the Vedânta may be traced in Nos. 5, 8, 10, 20, &c. The scheme is not intended as a refutation of the views, as a whole, held by any special school or individual, but as a statement of erroneous views on two special points, namely, the soul and the world. However this may be, we find an ample justification in this comprehensive and systematic condemnation of all current or possible forms of the soul-theory for the prominence which the author of the Milinda gives to the subject.

The other points on which the Milinda may be compared with the Kathâ Vatthu will need less comment. The discussion in the Milinda as to the manner in which the Divine Eye can arise in a man 2, is a reminiscence of the question raised in the Kathâ Vatthu III, 7 as to whether the eye of flesh can, through strength of dhamma, grow into the Divine Eye. The discussion in the Milinda as to

how a layman, who is a layman after becoming an Arahat, can enter the Order 1, is entirely in accord with the opinion maintained, as against the Uttarâpathakâ, in the Kathâ Vatthu IV, i. Our Milinda ascribes the verses,

'Exert yourselves, be strong, and to the faith,' &c.,

to the Buddha 2. In the note on that passage I had pointed out that they are ascribed, not to the Buddha, but to Abhibhû in certain Pitaka texts, and to the Buddha himself only in late Sanskrit works. In the exposition of Kathâ Vatthu II, 3 the verses are also ascribed to the Buddha. The proposition in the Kathâ Vatthu II, 8 that the Buddha, in the ordinary affairs of life, was not transcendental, agrees with Nâgasena's argument in the Milinda, part ii, pp. 8-12. The discussion in the Milinda as to whether an Arahat can be thoughtless or guilty of an offence 3 is foreshadowed by the similar points raised in the Kathâ Vatthu I, 2; II, 1, 2, and VIII, 11. And the two dilemmas, Nos. 65 and 66, especially as to the cause of space, may be compared with the discussion in Kathâ Vatthu VI, 6, as to whether space is self-existent.

The general result of a comparison between these two very interesting books of controversial apologetics seems to me to be that the differences between them are just such as one might expect (a) from the difference of date, and (b) from the fact that the controversy in the older book is carried on against members of the same communion, whereas in the Milinda we have a defence of Buddhism as against the outsider. The Kathâ Vatthu takes almost the whole of the conclusions reached in the Milinda for granted, and goes on to discuss further questions on points of detail. It does not give a description of Arahatship in glowing terms, but discusses minor points as to whether the realisation of Arahatship includes the Fruits of the three lower paths 4, or whether all the qualities of an Arahat are free from the Âsavas 5, or whether the knowledge of his

emancipation alone makes a man an Arahat 1, or whether the breaking of the Fetters constitutes Arahatship, and whether the insight into Arahatship suffices to break all the Fetters 2, and so on.

The discussion of these details gives no opportunity for the enthusiastic eloquence of the author of our Milinda, and the very fact of his eloquence argues a later date. But there can be no doubt as to the superiority of his style. And I still adhere to the opinions expressed in the former Introduction that the work, as it stands in the Pâli, is of its kind (that is, as a book of apologetic controversy) the best in point of style that had then been written in any country; and that it is the masterpiece of Indian prose.

T. W. RHYS DAVIDS.

TEMPLE,

May, 1894.

Footnotes

xi:1 Called on the title-page 'Catalogue of the Chinese Translation of the Buddhist Tripitaka.' But this must surely be a mistake. It includes a number of works which are not translations at all, and translations of a large number of others which do not belong to the Pitakas.

xi:2 No. 1358 in the Catalogue. Translated under the Eastern Tsin Dynasty, 317-420.

xi:3 As there is nothing about this curious Introduction in either of M. Specht's papers to be mentioned immediately, it seems possible that there are really three Chinese books on the same subject.

xii:1 It would be very interesting to have this point decided; namely, whether the volume in the India Office Library is identical with either of the two very different books in Paris. If not, we have, then, still another Chinese book on Milinda.

xii:2 Vol. i. pp. 520-529.

xv:1 'Transactions of the Ninth International Congress of Orientalists,' vol. i, p. 518.

xvi:1 Julien's translation, vol. i, pp. 173-178, and Mr. Beal's own translation, i, 147-157. There are two or three incidental references to the Council in other works. See my 'Buddhism,' p. 239.

xvi:2 St. Julien, 'Voyages des Pèlerins Bouddhistes,' vol. i, pp. 177, 178.

xvi:3 Beal, 'Buddhist Records of the Western World,' vol. i, p. 155.

xvii:1 In the 'Revue de l'Histoire des Religions' for 1893 (which has only just reached me), p. 258.

xvii:2 The 'Comptes rendus des Séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-lettres,' 1893, p. 232.

xvii:3 'Nepalese Buddhist Literature,' p. 60.

xviii:1 Chapter XXIX, p. 171, of Turnour's edition.

xviii:2 Turnour has Vattaniyâ-senâsanu.

xix:1 Turnour, pp. 1-73

xxi:1 Kathâ Vatthu I, 1.

xxi:2 Milinda, i, pp. 40-41.

xxi:3 Milinda, i, p. 48.

xxi:4 Milinda, i, pp. 86-89.

xxi:5 Milinda, ii, pp. 85-87.

xxi:6 Vinaya Texts (S. B. E. XIII), part i, pp. 100, 101, and Anguttara Nikâya.

xxv:1 Introduction, p. 57.

xxv:2 Milinda, i, pp. 179-185.

xxvi:1 Milinda, ii, pp. 96-98 (compare 57-59).

xxvi:2 Milinda, ii, p. 60.

xxvi:3 Milinda, ii, pp. 98 foll.

xxvi:4 Kathâ Vatthu IV, 9.

xxvi:5 Kathâ Vatthu IV, 3.

xxvii:1 Kathâ Vatthu V, 1.

xxvii:2 Kathâ Vatthu V, 10, and X, 1.