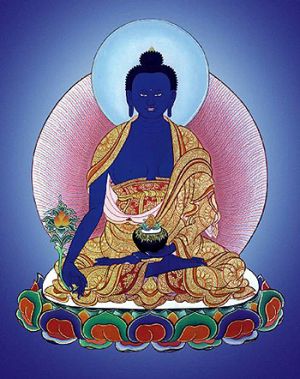

Medicine Buddha – Sang-rgyäs-smän-lha

Very Venerable Chöje Lama Phuntsok

Medicine Buddha – Sang-rgyäs-smän-lha

Presented at Karma Theksum Tashi Chöling in Hamburg, December 2009.

This article of teachings that Venerable Chöje Lama Phuntsok generously imparted

is dedicated in memory of His Eminence the Third Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche,

Karma Lodrö Chökyi Senge (1954-1992)

to the long life of His Eminence Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche, Lodrö Chökyi Nyima,

His Holiness the 17th Gyalwa Karmapa, Ogyen Trinley Dorje, and

all prestigious Khenpos and Lamas of the Karma Kagyü Lineage, and

to the preservation of the pure Lineage of Jamgon Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye.

First I would like to greet everyone and say tashi-delek. I am very happy to be at Karma Theksum Tashi Chöling in Hamburg and to discuss Medicine Buddha with you.

Whichever deity yoga we want to practice, we need to understand the meaning of the deity (yid-dam in Tibetan) and know how to practice. Everybody has different wishes and needs and therefore there are the various yidam practices. Why are we interested in Medicine Buddha? Due to the karma we created and accumulated in past lives, we suffer from various physical sicknesses and illnesses in this life. If somebody is sick and needs to become well, then

Medicine Buddha practice is right for that person. Just hearing the name of Medicine Buddha when we are sick is already very helpful and that is why we want to learn about him. It is like hearing the word “water” when we are very thirsty and focusing our attention on having a glass. Actually, all Buddhas and Bodhisattvas made aspiration prayers and wish to help us, but Medicine Buddha is the yidam deity that best helps those persons suffering from sicknesses, illnesses, and diseases.

Medicine Buddha’s Tibetan name is Sang-rgyäs-smän-lha in Tibetan. The syllable lha in his name is a general term that means ‘divinity, celestial being.’ sMän means ‘medicine,’ so Män-lha is a deity specialized in medicine. There are three aspects of the term lha, which we translate as ‘deity.’ The first aspect is a deity’s meaning (dön-kyi-lha), the second aspect is a deity’s characteristics (rtag-kyi-lha, ‘mark, sign, indication’), and the third is a deity’s symbolic aspect (bda’i-lha). Transcendent deities are other-worldly deities that have all three aspects.

Meaning in this context refers to a deity’s ultimate nature, which is the dharmakaya, ‘wisdom, truth body’ (chös-sku in Tibetan). A deity’s marks are the resultant sambhogakaya (long-spyöd-rdzog-pa’i-sku, ‘the body of perfect enjoyment’). The symbolic aspect of a deity is the nirmanakaya (sprul-pa'i-sku, ‘manifestation body’).

Sangye Menla has all three aspects, i.e., he personifies them. Is he the only yidam who has and manifests these three aspects? No, this applies to every yidam deity, e.g., Chenrezig, White Tara, Manjushri, and any yidam we meditate. Their meaning, i.e., their dharmakaya aspect, is not different but is the same. Their marks, i.e., their sambhogakaya characteristics, are not alike, though, which is already evident by the different names they have and by their different looks. We can understand this by imagining seeing smoke on a distant mountain top, which is an indication that there is a fire. In the same way, we know that the dharmakaya is manifest when we see specific marks of a yidam.

The terms yid-dam and lha are synonymous. Yidam is translated as ‘deity,’ but the Tibetan term actually means ‘a promise.’ It is the commitment (dam-tshig, ‘oath, vow, promise’) that we made or make to meditate a specific deity that harmonizes best with our wishes and needs. There are a variety of yidam deities that we can be committed to and that appear differently. Some are white, others are red, or blue, or yellow, or green. They can have different forms. They can be male or female, peaceful or wrathful, and so forth, but their ultimate meaning is the same.

For example, imagine a shop that sells a large assortment of different-colored candy. We will buy the candy that we like the most, but actually all sorts are sweet. The characteristic of candy is that it is sweet, but everyone has preferences. In that way, some of us trust green deities, others place more trust in white deities, and so, because we strive to realize the dharmakaya, we engage in different sambhogakaya practices. Just like there are different sorts of candy, there

are different yidam deities, but their meaning is not different because they all have the same essence. In our example, we will not experience that the candy we bought is sweet unless we taste it. When we have tasted the white candy, the red candy, the blue candy, the yellow candy, and the green candy, then we will not doubt but will have realized that all sorts are sweet.

When speaking of a deity, we always have the result in mind, which is to become free of all negativities and to have all good qualities. What is the dharmakaya, the ultimate aspect of every deity? It manifests nowhere else than in our own mind, nga-rang-gi-sems. But at this time, our mind is covered by faults and therefore the true nature of our mind, the dharmakaya, cannot manifest purely. Just like milk has the

potential to become butter, everybody’s mind has the dharmakaya. We are still at the stage of milk and haven’t become butter yet. As long as we are still like milk, we are called “humans.” If we work on ourselves and practice, then we will achieve the result, which in our example would be butter; in terms of being a human, it would mean having become a buddha.

A Buddhist is somebody who turns his/her mind inwards, which means practicing to become a buddha; in our example, working on turning milk into butter. We know that it is possible to make butter out of milk and that it is impossible to make butter out of water. This example shows that without the potential to become a buddha, it is impossible to become a buddha.

The terms “deity (lha)” and “yidam” are not used anymore when speaking about mahamudra (phyag-rgya-chen-po, ‘great symbol’). Then we speak of ground mahamudra, path mahamudra, and fruition mahamudra. Ground mahamudra is the view, e.g., appreciating and recognizing that milk has the potential to become butter, which, when accomplished by practicing the path, is fruition mahamudra. In terms of yidam deities, fruition mahamudra is realization of the dharmakaya, i.e., the ground that manifests as the sambhogakaya. It is a transformation process that takes place in our mind.

We saw that the third aspect of a yidam is the symbolic aspect, which is the sign of a yidam’s first aspect, which is the meaning. As to Medicine Buddha, the blue color of his body symbolizes the dharmakaya. We saw that the symbolic aspect of a yidam is the nirmanakaya. We can see anybody who teaches us how to meditate a yidam and grants the empowerment to meditate a yidam as a symbolic manifestation of that specific yidam.

To realize the meaning of Medicine Buddha, we need to practice the path of Medicine Buddha who appears in the sambhogakaya form. We meditate the sambhogakaya-yidam in reliance upon the instructions we receive from our Root Lama, who teaches us through the nirmanakaya. We practice the path in reliance upon the instructions about the sambhogakaya form that were given to us by a manifestation that appeared in an ordinary nirmanakaya form. In that way, we will be able to ascertain the dharmakaya, the meaning. This procedure is the same for any yidam we wish to meditate. Whether we meditate Vajrasattva, White Tara, Noble Chenrezig, or another deity, all yidams have these three aspects that we need to understand if we want to realize the dharmakaya, ‘the truth body.’

We will have difficulties if we do not know that all yidam deities have these three aspects. For example, if we do not know that all brands of chocolate and all sorts of candy are sweet, then we will not understand why there is such a great variety, and we certainly would not be able to work our way through all of them to overcome our increasing doubts when we see them in a candy store. In that way, it is important to understand the three aspects of every yidam, which also applies to Medicine Buddha. He is the yidam that sick people should believe in and trust.

What is the basis of sicknesses? The body that we received when we were conceived and took birth. Our mind experiences the pain that arises in our body when we are sick. In Buddhism, it is taught that when one, or more, or a combination of two or all three humors are imbalanced, we are sick. The three humors, i.e., the vital energy forces, are: air or wind (rlung), bile ([[mkhris]), and phlegm (bäd-kän). When our humors are balanced, we are healthy. We can get all kinds of sicknesses, though, and should consult a doctor when we are not well.

Buddhism speaks about three types of doctors. They are referred to as “the best, mediocre doctors, and normal doctors.” When we speak of the best doctor, we mean Medicine Buddha. He is the doctor who can heal the mind and therefore the body. As described in the “The Medicine Buddha Sadhana,” mediocre doctors are Medicine Buddha’s entourage that consists of Indra, Brahma, etc. Normal doctors are those doctors we consult in daily life. The three types of

doctors coincide with the three aspects of a yidam. The best doctor, Medicine Buddha, is the dharmakaya. Mediocre doctors are representatives of the sambhogakaya, and normal doctors are nirmanakaya appearances who we need and usually rely on when we are sick. We need Medicine Buddha to keep our mind well so that our body is well, too.

There aren’t many hospitals in Asia, so we are accustomed to relying on Medicine Buddha to help us when we are sick. It is our tradition, while Westerners are used to calling a doctor or going to the hospital when they are sick. But illness isn’t exclusively a physical matter because the mind experiences the pain of a sickness and suffers. It would be best to combine the two traditions and rely on both Medicine Buddha and normal doctors. So, that’s how it is.

We can say that all good doctors belong to the entourage of Medicine Buddha and are nirmanakaya appearances, and we need not think that a nirmanakaya must wear red robes. There are many large and good hospitals in Germany, and the doctors working in the hospitals are specialists. We can see them as nirmanakaya manifestations of Medicine Buddha. But the very best doctor is our own mind, and we should think about this. Many participants are in this seminar and I am sure that there are a few doctors who are specialists among them.

Again, it is very important and beneficial to understand the three aspects of a yidam. It would be a mistake to think that Medicine Buddha is an external authority who comes down from on high and heals us when we are sick. When we meditate Medicine Buddha, we are dealing with his sambhogakaya manifestation of characteristics. The same with Vajrasattva. For example, if someone has a painting of Vajrasattva and meditates on him, then it is the characteristics’ aspect and not the aspect of meaning.

If we engage in a specific practice, we did receive instructions on how to meditate a yidam from a teacher. There are different teachers who can be of help. They are symbolic aspects of the yidam, and we practice the characteristics’ aspect of the yidam. Every yidam has all three aspects, i.e., the aspect of the meaning, the aspect of characteristics, and the symbolic aspect. Any yidam that is most appropriate for our needs and we trust the most is our yidam. This concludes the general discussion about yidams. It is very beneficial and important to know about them.

Before continuing, let us meditate for a short while. Every one should meditate their yidam or the practice they are used to. Whichever practice we do, meditation means focusing our mind on the object we have chosen. In vajrayana, we cultivate shamata (‘calm-abiding meditation’) while meditating on a yidam. We sit straight and focus our attention one-pointedly on our yidam’s seed syllable that is on a moon disc in the center of our heart.

There is no space, so to speaking, to follow after thoughts concerning the past or future if we keep our attention one-pointedly on an object that we chose to meditate on, which is what mental quiescence means. Although we might be sitting straight, we will not be meditating if we don’t hold our mind one-pointedly on the object of meditation. Even monkeys can look like they are meditating, but usually they jump around. While we are not engaged in calm-abiding meditation, our mind is like a monkey that jumps around.

If we meditate Vajrasattva or do Guru-yoga, we imagine that they are above the crown of our head and focus our mind on them for a short while. Those of you who have a yidam, imagine its seed syllable on a moon disc in the center of your heart. If we try to meditate too long, mistakes arise. There is a Tibetan saying: “Absorption is the basis of sleep. If one tries to abide in absorption too long, one falls asleep.” Tibetans very often get itchy when they meditate for an extended period of time, and scratching oneself incessantly is not the best medicine. So it is important to meditate for short periods but a few times each day.

Just as milk has the potential to become butter, our mind has the potential to achieve buddhahood. If we do not realize our potential, then buddhahood lies dormant within us and remains undisclosed.

The Tibetan translation of the Sanskrit term buddha and buddhahood is sang-rgyäs. The syllable sang means ‘fully purified, immaculate,’ and the syllable rgyäs refers to ‘increased appearance of good qualities.’ That is the meaning of enlightenment or buddhahood, which is our mind. When we have purified our mind of all negativities and obscurations and thereby all the good qualities that we have are disclosed and manifest freely, then we

will have transformed our mind into an awakened mind and thus will have attained the perfect result, which is buddhahood. Presently, our mind is the basis for buddhahood. Again, buddhahood is within our own mind and is not given to us or created by an external authority. Just like milk is the basis for butter and without it no butter can be won, being a human being who has a mind is the basis to realize buddhahood.

Before granting the Medicine Buddha empowerment and explaining the practice, I want to speak about meditation in general. It is divided into the time we are engaged in the actual meditation practice and the time afterwards.

Meditation means being concentrated on the practice we have chosen. Anything we experience and do after having concluded a meditation session is called “post-meditation.” This is daily life and activities such as walking around, sitting, sleeping, eating, conversing with others, and so forth. During a

meditation session, we try to let our mind rest by not following after thoughts about the past, present, or future. That is the purpose of meditating. It is the opposite during post-meditation. We follow after thoughts about the past, present, and future that arise during post-meditation. We need to integrate meditation and post-meditation in our lives.

A day and night consist of 24 hours, and we spend about an hour, at the most two hours, practicing meditation. So we spend much time in post-meditation. What do we do during this time? Everybody is free to decide for themselves. If we subtract the hours that we sleep, we follow after our thoughts most of the time, and the time we spend in meditation is quite short.

We can only achieve peace and stability of mind if we are able to spend the post-meditative time in ease. That is how to achieve peace. What do we need to do to be at peace? We have to be able to concentrate our attention on what we are doing one-pointedly. What is the method? Integrating meditation and post-meditation. Which meditation practice do we engage in? It is an individual matter. Many disciples practice calm-abiding meditation (shamata in Sanskrit, zhi-gnäs in Tibetan). Other practitioners engage in Guru-yoga, while others meditate a yidam.

In short, the purpose of zhi-gnäs is to train our mind to abide in quiescence. We gather experiences while meditating in this way, and do not gather experiences if we do not practice calm-abiding meditation. Lacking experiences, we cannot know what occurs in our mind and as a result cannot gain certainty of the way our mind is and the way it appears.

In Buddhism, various levels of practice are differentiated. Cultivating calm-abiding is sutrayana practice. In vajrayana, we engage in the creation and completion meditation practices of a yidam. Both the sutrayana and vajrayana methods enable practitioners to abide in calm and ease. When we are able to do so, then we will be less inclined to follow after thoughts, and during post-meditation we will remember what it means not to become lost in distracting thoughts. This eventually becomes a very beneficial habit.

Thoughts aren’t always bad. We can differentiate between positive thoughts and negative thoughts. Due to having become skilled at being aware and mindful of thoughts through meditation, we have better thoughts during post-meditation. We have countless thoughts every day. We can say that people who do not practice meditation and therefore aren’t aware of their thoughts have more negative thoughts than positive thoughts. In

Buddhism, our endeavour to have positive thoughts is seen as a virtuous activity and having negative thoughts is considered a non-virtuous activity. Some people think that it makes no difference if they have positive or negative thoughts, but it isn’t like that. Non-Buddhists also know that positive

thoughts lead to positive actions and negative thoughts lead to negative actions, which is what karma means. For example, anybody who intends to steal something has a negative thought. Carrying this intention out is called “theft,” which is a negative action and thus bad karma for that person. Thinking about something good to do for others is a positive thought and leads to good karma. The more thoughts we have to help others, the better, i.e., all the more good karma. So, there are many ways we can think.

Our actions are based on our thoughts. It is a fact that anybody who has good thoughts and is of service to others accumulates good karma, and that anybody who has unwholesome thoughts and hurts others accumulates negative karma. This is not restricted to Buddhists but is valid for everyone. If it weren’t so, theft wouldn’t be considered a crime and thieves wouldn’t be punished in every country.

Where do thoughts to steal and thoughts to give something to others arise? In our mind, sems. Our mind thinks. The essence of everybody’s mind is identical, but our thoughts and intentions are different. Even the essence of an elephant’s mind and that of a mouse are identical, nevertheless, different things occur in their minds. Nobody can say that the size of a brain has something to do with thoughts, so a mouse is possibly smarter than an elephant. The essence of everyone’s mind is the same, but everyone has different thoughts. When we meditate a yidam and cultivate our practice, we are engaging our discursive mind, sems.

When we meditate Medicine Buddha, we think that his body is blue and so forth. Everybody who meditates a yidam is thinking about what the deity looks like. While meditating Medicine Buddha, we focus our attention on him. During post-meditation, we focus our attention on what we are doing, and - as it is - we always have thoughts that deal with the past, present, or future. We can say that we are occupied with our yidam when we meditate and with other things during the time we aren’t meditating.

We saw that there are the three aspects of Medicine Buddha, which are the meaning, the characteristics, and the symbolic aspect. When discussing how to practice the Sadhana of Medicine Buddha as a yidam, we look at his characteristics in detail.

Sangye Menla Sadhana

It is written in “The Sadhana of Sangye Menla”:

“Therein is contained the Lapis-Lazuli River Sadhana to the Medicine Buddha, taken from the Revealed Teachings, a fragment of the Vast Contemplation.

“NAMO MAHA BEKANZE YA

“To practice this, one first gathers the accumulations by offering a mandala, etc., or whatever pleasant offerings one can afford before a representation of the Medicine Buddha. If this is not practicable, it is alright to visualize the Medicine Buddha vividly present before oneself and then mentally create offerings. Then one needs nothing else.

“This particular Sadhana belongs to the anuttara class of tantra and so there are no special requirements of abstinence from meat or alcohol or of bathing or observing certain fasting habits. Because it is from the anuttara class of tantra, one definitely needs to have obtained empowerment and scriptural authority to practice.

“This Nyingmapa style of visualization has a simultaneous and spontaneous generation of the ‘before oneself’ and ‘as oneself’ mental forms of the buddha-aspect and this removes the need for a progressive build-up of the visualization. One imagines the various stages in accordance with the description in the text, as one recites.”

One should focus ones attention on the meaning of the words of the Sadhana, therefore it is best to recite it in ones native language. Of course, practitioners can recite the text in Tibetan, but they should also look at the translation. I met a man in Taiwan who was meditating Guru Rinpoche as his yidam. He told me that he recited the ritual text in Tibetan because he thought that Guru Rinpoche would not understand him if he recited it in Chinese. But this man did not know Tibetan.

I told him that it is irrelevant for Guru Rinpoche which language a disciple speaks, rather, it mattered for the practitioner to understand what he is reciting. Therefore, it is most beneficial to recite the text in our native language or in both languages.

Translations are available. The mantra of Vajrasattva and other yidam deities are in Sanskrit. Tibetans do not know the meaning of the syllables of the mantras either. The Nepali language uses the Sanskrit script, so Nepalis have no difficulties reading the mantras.

They laugh at foreigners and boast, “We can read the mantras. You can’t.” So, even if you can read Tibetan, you probably have difficulties pronouncing the language correctly. The main thing is the meaning and not the words. Reciting in your native language makes it so much easier for you because then you don’t need an explanation. Ma-red-päs, ‘Isn’t it so?’ The text is presented in three parts. They are: the introduction and preparations, the main practice, and the conclusion.

1. The Introduction

The introduction consists of “The Refuge Prayer and Bodhicitta Prayers.” Firstly, “The Refuge Prayer” is: / NAMO - I take refuge in the three rare and precious principal refuges, in the three root refuges, and all that constitutes a true refuge. /

The general and exceptional refuges are addressed in this prayer. The general refuges belong to the sutrayana and are the three rare jewels, the Buddha, the Dharma, and the noble sangha; they belong to the sutrayana. The exceptional refuges are the three roots, the Lama, yidams, and protectors; they belong to vajrayana.

In the next verse we recite “The Bodhicitta Prayer,” which is: / I give rise to bodhicitta in order to be able to help all beings attain buddhahood. //

Bodhicitta is the Sanskrit term that is translated into Tibetan as byang-chub-kyi-sems and means ‘having a mind filled with compassion’ (snying-rje in Tibetan). Three aspects of compassion are taught in Buddhism. They are compassion focused on the Dharma, compassion focused on living beings, and non-referential compassion. In the context of Medicine Buddha, directing our compassion towards all living beings is most important.

2. The Main Practice

In order to perfect the accumulation of merit, we first make offerings and recite praises. The material substances that we offer need to be blessed, which we do by reciting the next lines in the text: / Vast clouds of offerings such as the mandala, the seven royal attributes, etc. emanate from the originally pure nature and fill the whole of earth and space. Becoming inexhaustibly vast, they are offered by offering goddesses. PU SA HO /

The syllables PU SA HO are Sanskrit and mean ‘offerings.’ The offerings are the substances in our eight offering bowls. The bowls contain pure water for drinking and washing, fresh flowers, incense, a butter lamp or candle, perfumed water, food, and an instrument for music. Imagining the offerings and talking about them are thoughts. Is this a good or bad conceptual activity? It is a good conceptual activity.

The text continues with “The Four Limitless Contemplations.” The lines are: / May all beings be happy and free of suffering. May their happiness never decrease, and may they always abide in equanimity. /

Having spoken the prayer, we recite the Sanskrit mantra:

/ ==OM SVABHAVA SHUDDHA SARVA DHARMA SVABHAVA SHUDDO HANG== /

This mantra means ‘all phenomena are emptiness.’ When saying the mantra, in our mind we imagine that all impure appearances (called “dharmas,” chös in Tibetan, ‘phenomena’) transform into emptiness, i.e., primordial purity.

The next lines describe the procedure of imagining Medicine Buddha. We recite the lines: / Then, both ‘as oneself’ and ‘before one,’ within the void nature of this giga-cosmos appears a celestial palace, in the center of which is a lion-throne. On this is a lotus, upon which appears the dark blue seed syllable HUNG. This becomes the Medicine Buddha. His radiant body of light is lapis-lazuli in color. He wears the three garments of a monk and holds the arura plant in his right hand. His left hand is in the meditation position and holds a begging bowl. Resplendent with the signs of perfection and achievement of a Buddha, he sits in the vajra-posture. /

Then we visualize his entourage as described in the text that we recite: / On the petals of the lotus of the visualization before me are the seven Medicine Buddhas, Buddha Shakyamuni, Indra, Brahma, etc., and the Dharma scriptures. Behind them are the sixteen mahabodhisattvas, and behind those are the ten worldly protectors and twelve leaders, each accompanied by their corresponding entourages. The four gates are guarded by the four great kings. /

Then:

/ Light radiates from the three places and from the syllable HUNG. This light goes to the buddhas of the eastern quarter, inviting them to animate the visualized forms with their presence. From each of their buddha fields their countless wisdom gods and goddesses come and dissolve into both myself as the deity and the deity in front. /

Having transformed appearances into emptiness and having imagined the palace of Medicine Buddha, then having visualized him and his entourage, we recite: / HUNG - May the eight Medicine Buddhas and the gathering of all deities that have been invited here cause a mighty rain of blessings to fall. May they bestow the supreme empowerment on these devoted and fortunate disciples, removing any obstacles to their life-force or anything which creates setbacks.

Then we recite:

NAMO MAHA BEKANZE YA – SAPARIVARA - BENZA SAMAYA SA SA - BENZA SAMAYA TITRA LHEN - OM HUNG TRAM HRIH AH - ABHIKENSA HUNG

These Sanskrit words are a repetition of the foregoing request and are recited while making the respective hand gestures. The mudra of the first part of the mantra is the physical expression of requesting that the assembly appear, which is spoken with the words NAMO MAHA BEKANZE YA – SAPARIVARA – BENZA SAMAYA SA SA. The syllables BENZA SAMAYA TITRA LHEN are spoken while doing further mudras and are the request that the assembly stay and not leave. OM HUNG TRAM HRIH

AH symbolize the five buddha families. The five buddha families (rgyäl-ba-rigs-lnga, ‘five victorious ones’) are: Vairocana, Akshobhya, Ratnasambhava, Amitabha, and Amoghasiddhi. We recite their seed syllables to call them because we wish to receive their empowerments. The five seed syllables of the five buddha families are spoken while making the respective mudras. ABHIKHENSA HUNG means ‘please grant the empowerment.’ Having the wish to make offerings to them, we are the ones who recite the entire mantra and who make the mudras to firmly establish Medicine Buddha and the visualized assembly.

We make offerings by imagining that light streams from our heart center and on its rays countless goddesses (ye-shes-pa in Tibetan) bring the countless precious offerings to the deities. The text, which we recite, gives an account of the offerings:

/ HUNG - I offer flowers, incense, light, perfumes, delicacies, music, and so forth, as well as forms, songs, scents, flavors, and textures to the deities. May I complete the two accumulations. /

While making the respective mudras, we recite the Sanskrit version of the offerings, which is:

OM BENZA ARGAM PADAM PUPE DUPE ALOKE GENDE NEWIDE SHAPDA RUPA SHAPDA GENDE RASA SAPARASHE DRATISA HUNG

Just as we do not immediately give guests the main meal when they arrive at our home, we first offer the deities water, which is the meaning of the syllable ARGAM. We imagine that the countless offerings that we send to all deities in the vast expanse of space reach them and when it does, we speak the last syllables DRATISA HUNG, which means ‘please accept.’

We make more offerings that are listed in the next verse:

/ HUNG - I offer the eight principal substances, the excellent king-like white mustard seed and so forth to the deities. May I complete the two accumulations. MANGALAM ARTHA SIDDHI HUNG /

Again, the Sanskrit is a repetition of the verse. Then:

/ HUNG – I offer the eight principal auspicious symbols, the excellent king-like vase and so forth to the deities. May all beings complete the two accumulations. MANGALAM KUMBHA HUNG /

Again, the Sanskrit expresses the verse, also in the next lines:

/ HUNG – I offer the seven precious things, the finest of all pleasures, the excellent king-like jewel and so forth to the deities. May I complete the two accumulations. OM MANI RATNA HUNG /

Following, we make a mandala offering by reciting:

/ HUNG – I make the best of all offerings, that of Mount Meru and the four continents along with their sub-continents to the deities. May the two accumulations be perfectly completed. OM RATNA MANDALA HUNG /

Then we bring washing offerings:

/ HUNG – With sweetly scented water, I bathe the Tathagata’s perfect body. Although this deity is immaculate, this is done as a token of future purification of my misdeeds and obscurations.

OM SARVA TATHAGATHA ABIKEKATE SAMAYA SHRI YE HUNG

Then we imagine drying the Tathagata’s precious body and offering wonderful robes while reciting the next two verses: / HUNG – With a soft white sweetly-scented cloth, I dry the Victorious Ones’ body. Although it is already immaculate, this is done as a token of my future freedom from suffering. OM KAYA BISVA DHANI HUNG /

==HUNG== I offer these beautiful saffron robes for the Medicine Buddha to wear. Although his perfect body knows no cold, I offer them as a token of future increase in vitality. OM BENZA VASATRA AH HUNG /

Having made offerings, we praise Medicine Buddha. We practice in order to perfect the accumulation of merit. By praising Medicine Buddha, we pay obeisance to his qualities. We recite the praise:

==HUNG== I praise and pay homage to the Medicine Buddha who holds the most precious of all medicines, the one who has the eight mahabodhisattvas as entourage, who removes the sicknesses and sufferings of beings, and whose body glows like a mighty lapis-lazuli mountain. /

This is praising his qualities. Then we praise his entourage by reciting:

/ I praise and pay homage to the three most precious of all, the rare and sublime Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha: the one with marks of excellence, beautiful like jewels, the moon and gold, the Dharma-intelligence of Shakyamuni, the ocean of Dharma renown, the Dharma of sixteen sattvas, etc. /

Next to the entourage that consists of the other Medicine Buddhas, there is the worldly entourage, which is addressed in the third section of the praise:

/ I praise and pay homage to the amrita medicine deities, the hosts of rishis and medical knowledge-holders among men, Brahma, Indra, the great kings, the ten protectors of the directions, the twelve masters of the yakshas and their assistants, etc. /

This concludes the accumulation of merit by making offerings and praises and brings us to the main section of the practice, which is the practice of meditative absorption, i.e., focusing our mind one-pointedly on Medicine Buddha. The text tells us to “Recite the following while visualizing the mantra which encircles the HUNG of the heart center of both the yidam in front and oneself as the deity.”

The first section of the verse that we recite deals with visualizing ourself as Medicine Buddha. It is:

/ Many colored lights of various hues emanate from myself as offering and supplication to the Medicine Buddha in the lapis-lazuli pure dimension of the eastern quarter. /

We do not see our usual body but imagine that we are Medicine Buddha. To do this, we imagine the syllable HUNG on a moon disc in our heart center. We furthermore imagine that the mantra of Medicine Buddha encircles the syllable HUNG. The mantra is:

Thayata

Om Bekanze Bekanze Mahabekanze Radza Samudgate Soha

The seed syllable of Medicine Buddha is the Sanskrit syllable HUNG that is written in the Tibetan script. If we ask whether we have to visualize the Tibetan script, the answer is, no. We can and should imagine and pronounce the syllable in our native script and language. This applies to the mantra, too, which is Sanskrit but is written in the Tibetan script. We repeat the mantra in the sound of our native tongue.

As to the visualization, we see ourselves as being Medicine Buddha and do not see our usual body. We have all characteristics of Medicine Buddha. Our language is the mantra, and, without giving in to distractions, we keep our mind single-pointedly on the visualization and mantra repetition.

How should our mind be? Since the body, speech, and mind of Medicine Buddha are inseparably united with our body, speech, and mind, it is helpful to focus our attention single-pointedly and let our mind rest on the syllable HUNG in our heart center. How do we recognize whether we are fully concentrated on the syllable HUNG? If we look at ourselves from around the corner and notice that nothing else is on our mind, then it is a sign that our mind is abiding single-pointedly on the HUNG. If we notice that other thoughts have arisen in our mind, then we know that we are not abiding in the meditation practice.

Where is our mind? It is in our body and not anywhere outside our body. That is why it is important that our body is calm and steady during meditation practice because then our mind will be calm and at ease. When meditating, we sit in what is called “the seven postures of Vairocana.”

The forefathers of the Kagyü Lineage always said: “A stable posture helps our mind be calm.” Our body is the basis for meditation. If we take care of and heed our body, then our basis will be good. For some people it is more comfortable and easier keeping their back straight by sitting on a chair. If we prefer sitting on the floor, we need the good and comfortable support of a meditation cushion. Then our mind will be influenced positively and our meditation can go well.

When we meditate, it is good to sit in the seven postures of Vairocana because the wind or air energy of our body and mind are inseparable. The wind energy moves in the body’s channels. If the channels, which are the bases of the body, are natural and straight, then the wind energy moves smoothly through the body and the mind is at ease. In that case, both are free and conceptual activities are pacified and decrease. If we sit properly, then we become less distracted and can easefully visualize ourselves as Medicine Buddha and meditate the HUNG on the moon disc in our heart. This is very beneficial because less faults occur.

Two faults can arise during a meditation session. One is being distracted, and the other is being drowsy. We lose clarity and sharpness of mind when we are drowsy and sleepy. In that case, we aren’t focusing one-pointedly on the visualization. When this error arises, we slouch over or against a wall, our mala falls out of our hand, and we fall asleep without noticing how fast an hour or two have passed.

The time we set aside for meditation practice is over and we didn’t abide in mental quiescence. This is a big error that is neither meditation nor post-meditation. It isn’t laziness or work, either, rather, it is sleep. We can avoid this error by sitting straight.

In a nuns’ retreat center, 15 years ago, a nun had her text on a high table. She fell asleep and her head banged on her text. She woke up when the bell rang, sat up real fast, and couldn’t find her text that was stuck to her forehead until it fell down. So, we have to be very careful not to become drowsy and not to fall asleep. We should be aware of the moment we feel that we are drowsy and then sharpen our mind by adjusting our posture.

If that doesn’t help, we can do a short physical yoga exercise to become fully awake again. Tightening our fists won’t help, rather, we can do a light and refreshing exercise that doesn’t require that we stand up. To dispel sleepiness, we can lay our hands on our knees, shake our shoulders, and breathe out strongly through our mouth. When we are fully awake again, we focus one-pointedly on resting in mental quiescence.

The second fault that can occur while meditating is becoming distracted and agitated. Instead of focusing on the seed syllable, we think about the past or future. For example, our anger increases when we think about why we were angry the day before.

It happens that situations are bloated by thinking about them again and again, and then we aren’t concentrated on our meditation. This is a very big obstacle. We must remove this fault the moment we notice that it has arisen in us. We can curb it by leaning against the wall a little bit. We can also do a yoga exercise, like touching our shoulders and concentrating on them.

There used to be two retreat centers at Thrangu Rinpoche’s monastery. One day, the two retreat masters met and the one asked the other, “What are your retreatants doing and how are they?” He answered, “One retreatant thinks a lot. He imagined that he was carving an alligator out of the broomstick and one day actually did it. It happens that a retreatant does funny things.” The other retreat master said, “My retreatants circumambulate after they have finished doing the morning prostrations.

I’m not there when they do the prostrations, but I was told that while one retreatant remained seated comfortably, he again and again let a heavy sack that he had tied to a rope fall to the ground after having pulled it up each time. Everybody heard it and thought he was doing prostrations.” There are retreatants like that, but this is an extreme example for being distracted. In a meditation session, it would be best if our mind is focused on the visualization and if we don’t succumb to distracting thoughts. In any case, we need to be aware of distracting thoughts the moment they arise and do something about it.

In short, when we engage in the practice, it is important to be certain that we are Medicine Buddha - that our body is the body of Medicine Buddha; that through his mantra, our speech is the speech of Medicine Buddha; and that through the seed syllable, our mind is truly one with the mind of Medicine Buddha. We abide one-pointedly in this certainty when we engage in the main section of the practice. We can supplement the practice of abiding in quiescence by again repeating and visualizing the above verse of the Sadhana, which is:

/ Many colored lights of various hues emanate from myself as offering and supplication to the Medicine Buddha in the lapis-lazuli pure dimension of the eastern quarter. /

Then:

/ In response, from there large and small forms of the Medicine Buddha, their speech in the form of mantra-garlands, and their mind in the form of the tokens they hold in their hands (like the arura plant and the begging-bowl filled with amrita) descend like rain and dissolve into the visualization in front and the visualization of myself. /

It is very important and helpful to focus our attention on this visualization when we notice that our mind has become distracted. If no problems arise, we don’t have to add this to our practice more often. In short, the point is to hold our mind in single-pointedness. If we can keep our mind on the visualization, then our meditation is going well.

There are two ways to repeat a mantra, speaking it with our voice and only thinking it. While practicing this Sadhana of Medicine Buddha, it suffices to visualize the practice by repeating the mantra silently and by just thinking it.

This concludes the discussion of the main section of mental absorption. We can practice it for ½ an hour or longer, depending upon how much time we have.

3. Conclusion

It is written in the Sadhana: “Having recited as many mantras as one has time, one then focuses upon the front visualization, reciting:”

/ Having confessed every mistake and wrong, I dedicate all virtue to enlightenment. May there be the good fortune to be ever free from sickness, affliction, and suffering. /

Then we address Medicine Buddha’s worldly entourage and furthermore imagine the wisdom deities dissolving into us by reciting the next verse in the Sadhana, which is:

/ All worldly beings, return to your abodes. BENZA MU. The wisdom and visualized deities dissolve into me. There is just the vast expanse of goodness, which is the orginal purity. EMAHO //

When we say EMAHO, we imagine that the wisdom aspects of Medicine Buddha dissolve into us. Again, we enter the state of mental quiescence and do not engage in any discursive activities. Having remained totally relaxed, at peace, and at ease for a while, we rise from the state of mental absorption and dedicate any merit that we were able to accumulate through this practice for the welfare of all living beings. Then we enter the time of post-meditation.

It is written in the Sadhana: “This condensed text is a small part of the majestic work of the great master Raga Asay, and I hope that the buddhas will forgive anything in it that may not accord with its original intention. Through the virtue of this work, may all beings be freed from sickness and thereafter swiftly reach the state of the Medicine Buddha. Whatever this Sadhana contains in the way of comment, visualization, praise or offering, may it not be contradictory to the approach of the yoga tantra.

“There are many benefits arising from practicing this Sadhana from the depths of ones heart: if one is ordained and breaks the vows one should keep, then in spite of the downfall, one may, through this, purify all the possible negative karma which could cause rebirth as a hell-being, a ghost, or an animal. Then one will not take rebirth in those lower states of life. Even if one were to be reborn in such a state, then immediately after birth

one would transmigrate to the higher, happy realms and progressively work ones way to enlightenment. In this life, too, one will find nourishment and clothing without effort and not be overwhelmed by sickness, affliction, hard to remove troubles, or the gyäl-po affliction. One will enjoy the protection

of Vajrapani, Brahma, Indra, the four great kings, the twelve masters of the neuchin with their seven thousand-fold entourages. One will be liberated form the various dangers posed by the eighteen sorts of untimely death enemies, wild animals, and so forth, and ones aspirations will find complete fulfilment. These benefits explained in the two principal medical sutras are inconceivable.

“This Sadhana is the most widely practised of all the Medicine Buddha Sadhanas and was part of the regular ritual of many great seats of learning. Being transmitted in the vajra seat of Tibet at Lhasa by the great Lord Atisha and at Samye by the Great Bodhisattva, the Medicine Buddha practice belongs to the Nyingma and Sarma schools and one should be confident of its universality. Of the many forms of practice, this one is very concise and, belonging to the anuttara class, requires no special observances or torma – it is a mind exercise; however, please do it properly and completely!

“SHUBAM DZAYANTU

“This shortened form of the Medicine Buddha Sadhana from the revealed teachings was made by the master printers in Dogon Puntsok Darjay Ling. Through it may virtue and wholesomeness increase.”

file:///C:/Dokumente%20und%20Einstellungen/Gaby%20Hollmann/Eigene%20Dateien/greetings/dorjee.jpeg

Post-Meditation

Many thoughts regarding the past, present, and future arise in our mind during the post-meditation time. We have much time at our disposal during post-meditation, approximately 22 hours each day and night - 22 because we practiced meditation for 2 hours. It might have been possible not to gather strong habitual tendencies during the 2 hours that we meditated, but we succumb to them again when we have to deal with our daily obligations via our body, speech, and mind.

Even if we are not employed, we are always and unavoidably involved with something, e.g., eating, conversing, sleeping, and so forth. When we are involved with daily activities, we need a good reminder to help us carry our meditation experiences into the post-meditation period. A good help for the post-meditation period is to think that our mind is the mind of Medicine Buddha and that we are indivisible with him. If we can keep this in mind, then our post-meditation will be the practice of Medicine Buddha. This is so for any practice we are presently doing, whether Ngöndro, Guru-yoga, and so forth. We think of our object of meditation during post-meditation.

Hearing that we should think that we are Medicine Buddha and are not different from him doesn’t imply that we can be proud of ourselves or boast. If we aren’t careful, our negative emotions will increase. That is why Jetsün Milarepa told his disciple Rechungpa: “When I eat, I eat. When I walk, I walk. When I abide, I abide. When I sleep, I sleep.” This means to say that he had mindfulness and awareness in every activity of life, thus he turned post-meditation into

meditation. But we are still involved with our mind and thus become happy, angry, or sad. If we ask what we can do when this happens, then we can and should remember our yidam, in this case, that we are not different than Medicine Buddha. If we can rest in this thought, our negative emotions will have less power over us and will decrease.

When obstacles and problems occur during post-meditation, it is very beneficial to cultivate the habit of remembering that we are the yidam we have chosen to meditate. Our yidam is always at our disposal. Instead of circling around in thoughts that arise, we serve our yidam in the best way by remembering him, and thus we cultivate our mind in the best way. It is not a point of carrying on a tradition. Traditions are restricted to habits that people of specific countries or nations are used to. We do not need to follow them, rather, it is important to develop our mind. Dharma practice benefits our mind positively.

We looked at the general purpose of engaging in a yidam practice and spoke about the three aspects of a yidam. We saw that the main practice deals with the apparent marks of Medicine Buddha, which is the sambhogakaya. The paintings, statues, and photos of Medicine Buddha that we can see always depict his second aspect and can never be the first aspect, which is the meaning. The aspect of meaning is the realization that we are inseparable with Medicine Buddha. It is good

to have the support of an illustration of Medicine Buddha to see his characteristics, but it isn’t really necessary. For example, a photo of a mother will not replace her. If we have a migraine headache, we need her to console us and not a photo of her smiling. In fact, it would be counterproductive if our mother smiled at us when we are in pain.

A yidam’s first aspect of meaning is the inseparability of the yidam and our mind. By meditating the main section of a yidam’s Sadhana, which deals with the apparent characteristics, we unify the deity’s meaning (dön-kyi-lha) and the deity’s characteristics (rtag-kyi-lha).

Let us meditate a short while together. We imagine that we are one with Medicine Buddha, focus our attention on the HUNG that is on a moon disc in our heart center, and recite the mantra. If any faults arise, we can do yoga exercises.

Beings experience a great variety of suffering, specifically due to physical sicknesses and illnesses. And so, we turn to Medicine Buddha.

Because he saw that living beings are stricken with physical illnesses and as a result suffer immensely, Medicine Buddha promised to fully offer his enlightened activities by protecting and helping beings become free of sicknesses and diseases. He promised that he would not rest until everyone is healed. If we call him with faith, trust, and devotion and make wishing prayers, we will experience his enlightened activity. Medicine Buddha has the power to help us, and if we call him, he is just like a mirror that has the capacity to reflect our image. That is exactly how we can experience him if we call him, and, in accordance with the vajrayana tradition, we therefore receive the empowerment. What is the purpose and meaning of an empowerment?

Empowerments are like sowing a seed in the ground. It is necessary to sow a seed if we wish to reap the fruit. Where is a seed sowed? In a field. The seed of an empowerment is planted in the container, which is our body, speech, and mind. When a seed has been sowed, it is necessary to provide it with moisture, manure, and good conditions so that it can ripen and grow. In the same way, doubts have arisen in our mind if we do not protect and tend

the seed of the empowerment that is planted in us. If we tend the seed, we are very likely to receive the blessing of Medicine Buddha when we engage in the practice during a meditation session and during post-meditation times. So, the empowerment is like a seed, sa-bon. Who plants the seed? The Lama who bestows the empowerment.

After the seed of an empowerment has been planted in us, it is up to us to protect and tend it. Just like goats uproot sprouts while eating in the field, great obstacles will arise if we do not take care of and tend the seed of the empowerment.

Having made the request, Lama Phuntsok offered teachings while kindly granting the Medicine Buddha empowerment. He taught:

To let Medicine Buddha grow, it would be best to constantly keep him in mind or to at least think of him and to repeat his mantra 108 times a day. If that is too much, we can repeat his mantra 21 times a day. If that is too much, we can speak his mantra 7 times a day. If it isn’t possible to speak his mantra at home, we can do so while driving. In any case, speaking his mantra at least 7 times in a row at home serves the purpose of not letting the seed of the empowerment completely dry up, but in that way allowing it to grow.

Since we have a body, we have all five aggregates (skandha in Sanskrit, phung-po in Tibetan). The skandhas are the five aspects that comprise the physical and mental constituents of a sentient being. They are form, feeling, distinguishing perception, mental formation, and consciousness. The five skandhas are the bases for unavoidable sicknesses and diseases. Due to specific situations and conditions, many sicknesses are quite intense, though. In such cases, it is very important to recite Medicine Buddha’s mantra. Nobody can say that they will never get sick. When we do, we rely on doctors to cure outer symptoms and on Medicine Buddha to heal us from the inside.

Buddhists recognize that there are two causes for sicknesses. One cause is negative actions that we created in the past and that ripen in us as sicknesses and diseases. The other cause is present circumstances and conditions. It is very helpful to imagine being inseparable with Medicine Buddha and to repeat his mantra when we feel anguish and are sad about being sick. His practice does not only benefit us but also helps others. It is very good for hospital doctors, nurses, and helpers to do their work with a pure heart. It benefits patients immensely if medical and social workers call Medicine Buddha, receive his blessing, and pass his blessing on to their patients.

As a sign of gratitude for having received the empowerment, disciples offered a mandala and recited dedication prayers, dedicating any good that arose from this auspicious event for the welfare of all living beings.

Dedication

Through this goodness, may omniscience be attained and thereby may every enemy (mental defilement) be overcome. May beings be liberated from the ocean of samsara that is troubled by waves of birth, old age, sickness, and death.

By this virtue may I quickly attain the state of Guru Buddha, and then lead every being without exception to that very state! May precious and supreme bodhicitta that has not been generated now be so, and may precious bodhicitta that has already been never decline but continuously increase!

May the life of the Glorious Lama remain steadfast and firm. May peace and happiness fully arise for beings as limitless in number as space is vast in its extent. Having accumulated merit and purified negativities, may I and all living beings, without exceptions, swiftly establish the levels and grounds of buddhahood.

Chöje Lama requested that we repeat “Karmapa khyenno” to help eliminate any impediments that obstruct His Holiness the Gyalwa Karmapa from coming to Europe.

Acharya Lama Drime Dawa, Resident Lama of Karma Theksum Tashi Chöling: “Firstly, I would like to say that we are very thankful to Lama Phuntsok for having given this wonderful initiation and the teachings. It made me very happy. The teachings were easy to understand and very special. It hasn’t been possible so far, but I am sure that we can do this practice at the center together once a month. It would help us keep the promise that we made to repeat the mantra and it would help us in our practice. In the name of everyone here, many thanks to Lama Phuntsok.