Manjushri

The bodhisattva Mañjushri)]

The bodhisattva Mañjushri)]

- See also :

- See also :

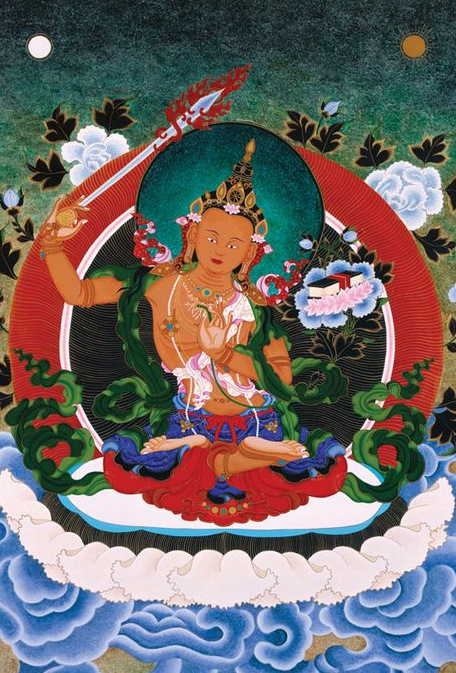

Mañjushri (Skt. Mañjuśrī; Tib. འཇམ་དཔལ་དབྱངས་, Jampalyang; Wyl. 'jam dpal dbyang) or Mañjughosha (Skt. Mañjughoṣa; Tib. འཇམ་དབྱངས་, Jamyang; Wyl. ‘jam dbyangs; 'the Gentle Voiced') is

- one of the eight great bodhisattvas who were the closest disciples of the Buddha.

In this form, he sometimes appears whitish-green in colour and holding a lily to symbolize renunciation of the destructive emotions.

- the embodiment of the knowledge and wisdom of all the buddhas, traditionally depicted with a sword in his right and a text in his left hand.

Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo says:

- In definitive terms, Mañjushri, you are now, and from the very beginning you have always been, a genuine buddha, in whom all the qualities of abandonment and realization are totally perfected, because you completely traversed all ten bhumis,

such as the Joyous and so on, and purified the two obscurations, together with any latent habitual tendencies, many incalculable aeons ago.

Nevertheless, from a merely provisional perspective, you appear as the foremost of all the bodhisattvas, and demonstrate the means of training as a bodhisattva in the presence of all the victorious ones and their heirs throughout the ten directions.

- Moreover, from the perspective of the mantrayana, there is no doubt whatsoever that you, Mañjushri, are a buddha. In fact, this is even stated in the sutras.

In the Sutra of the Array of Mañjushri’s Pure Land, for example, it says you have completed the ten bhumis.

And in two other sutras—the Shurangama-samadhi Sutra and the Angulimala Sutra—you are clearly referred to as a buddha. [1]

Footnotes

Further Reading

- Jamgön Mipham, A Garland of Jewels, (trans. by Lama Yeshe Gyamtso), Woodstock: KTD Publications, 2008

See Also

External Links

- Manjushri series on Lotsawa House

- A Few Remarks—An Explanation of the Praise to Noble Mañjushri known as Glorious Wisdom’s Excellent Qualities

- Manjushri outline page at Himalayan Art Resources

Source

Mañjuśrī (Ch. Wenshu; Jpn. Monju; Tib. ‘Jam-dpal) is one of the oldest and most significant bodhisattvas of the Indian Mahayana Buddhist pantheon.

The personification of the Mahayana notion of insight or wisdom (prajñā), Mañjuśrī or “Gentle Glory,” often functions in Mahayana texts as interlocutor: his pointed questions to the Buddha elicit the teachings his audience needs in order to grasp even the subtlest points of doctrine.

Like insight, Mañjuśrī is ever new; he is often portrayed as a golden-complexioned, sixteen-year-old “Crown Prince” holding aloft the sword of wisdom in one hand, and a Perfection of Wisdom book (Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra) in the other.

Although Mañjuśrī’s origins remain a point of lively scholarly debate, his importance to early Indian Mahayana is clear.

The bodhisattva appears in the earliest datable literary evidence of Mahayana works available in any language, the Chinese translations prepared during 168–189 CE by the Indo-Scythian scholar Lokakṣema and his team of translators.

Over the next centuries, Mañjuśrī featured in Mahayana literature of virtually every genre, from sutras and commentaries to esoteric (tantric) meditation manuals and litanies.

As the bodhisattva of intellectual excellence, Mañjuśrī was especially popular among Indian Buddhist monastics.

From the 6th century CE, his images were becoming a mainstay of Buddhist monasteries and temples.

By the 8th century CE, we find the Crown Prince represented as a multiarmed and multiheaded tantric figure, and in a proliferation of Mañjuśrī-centered mandalas.

The popularity of the Crown Prince was not limited to South Asia.

Mañjuśrī worship developed into one of the most important Buddhist cults of T’ang China, where he became closely identified with a mountain complex called Wutaishan (see Bibliographies).

In Japan, Mañjuśrī-related practices became associated with the Saidaiji order and esoteric Buddhist master Eison (b. 1201–d. 1290), who promoted Mañjuśrī worship among social outcasts (hinin).

The Crown Prince was renowned in Nepal as the creator of the Kathmandu Valley; the Svayambhūpurāņa reports that Mañjuśrī split a mountain in two with his sword to drain the waters of the Kālīhrada and open the space.

Mañjuśrī was an especially prominent feature of the Tibetan Buddhist landscape.

Scholars from all of the four major schools of Tibetan Buddhism claimed direct visions of the bodhisattva of wisdom; to see Mañjuśrī denoted a subject’s perfect insight into the Buddha’s teaching.

To this day, scholars of all backgrounds routinely invoke Mañjuśrī at the start of their own writings.

General Overviews

Overviews of Mañjuśrī run the gamut from in-depth scholarly to simple and concise.

Among the former, Lamotte 1960, a classic study, explores Mañjuśrī in multiple cultural contexts.

Tribe 1997 does an excellent job of expanding on Lamotte to unpack the bodhisattva’s possible origins.

On the lighter side, Birnbaum 2005 is especially strong on Mañjuśrī’s place in Chinese Buddhism, Harrington 2004 emphasizes his place in Indian Buddhist literature, and Suzuki 1921 touches on his Japanese incarnations.

Mañjuśrī’s portrayals in the earliest Mahayana literature are skillfully analyzed by Harrison 2000, and Hirakawa 1983 explores his broader significance to the nascent Mahayana movement.

For a solid general introduction to the bodhisattva’s philosophical undergirding and status as a devotional figure, Williams 2009 is an excellent starting point.

Mañjuśrī. (T. ’Jam dpal; C. Wenshushili; J. Monjushiri; K. Munsusari 文殊師利). In Sanskrit, “Gentle Glory,” also known as Mañjughoṣa,

“Gentle Voice”; one of the two most important Bodhisattvas in Mahāyāna Buddhism (along with Avalokiteśvara). Mañjuśrī seems to derive from a celestial musician (Gandharva) named Pañcaśikha (Five Peaks),

who dwelled on a five-peaked mountain (see Wutaishan), whence his toponym. Mañjuśrī is the bodhisattva of wisdom and sometimes is said to be the embodiment of all the wisdom of all the buddhas.

Mañjuśrī, Avalokiteśvara, and Vajrapāṇi are together known as the “protectors of the three families” (Trikulanātha), representing wisdom, compassion, and power, respectively.

Among his many epithets, the most common is Kumārabhūta, “Ever Youthful.”

Among Mañjuśrī’s many forms, the most famous shows him seated in the lotus posture (Padmāsana), dressed in the raiments of a prince, his right hand holding a flaming sword above his head, his left hand holding the stem of a lotus that blossoms over his left shoulder, a volume of the Prajñāpāramitā atop the lotus.

Mañjuśrī plays a major role in many of the most renowned Mahāyāna sūtras.

Mañjuśrī first comes to prominence in the Vimalakīrtinirdeśa, which probably dates no later than the first century CE, where only Mañjuśrī has the courage to visit and debate with the wise layman Vimalakīrti and eventually becomes the interlocutor for Vimalakīrti’s exposition of the dharma.

In the Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra, only Mañjuśrī understands that the Buddha is about to preach the “Lotus Sūtra.”

In the Avataṃsakasūtra, it is Mañjuśrī who sends Sudhana out on his pilgrimage.

In the Ajātaśatrukaukṛtyavinodana, it is revealed that Mañjuśrī inspired Śākyamuni to set out on the bodhisattva path many eons ago, and that he had played this same role for all the buddhas of the past; indeed, the text tells us that Mañjuśrī, in his guise as an ever-youthful prince, is the father of all the buddhas.

He is equally important in tantric texts, including those in which his name figures in the title, such as the Mañjuśrīmūlakalpa and the Mañjuśrīnāmasaṃgīti.

The bull-headed deity Yamāntaka is said to be the wrathful form of Mañjuśrī. Buddhabhadra’s early fifth-century translation of the Avataṃsakasūtra is the first text that seemed to connect Mañjuśrī with Wutaishan (Five-Terrace Mountain) in China’s Shaanxi province.

Wutaishan became an important place of pilgrimage in East Asia beginning at least by the Northern Wei dynasty (424–532), and eventually drew monks in search of a vision of Mañjuśrī from across the Asian continent, including Korea, Japan, India, and Tibet.

The Svayambhūpurāṇa of Nepal recounts that Mañjuśrī came from China to worship the Stūpa located in the middle of a great lake.

So that humans would be able worship the stūpa, he took his sword and cut a great gorge at the southern edge of the lake, draining the water and creating the Kathmandu Valley.

As the bodhisattva of wisdom, Mañjuśrī is propiated by those who wish to increase their knowledge and learning.

It is considered efficacious to recite his mantra “oṃ arapacana dhīḥ” (see Arapacana); Arapacana is an alternate name for Mañjuśrī.

Source

The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism by Robert E. Buswell Jr. and Donald S. Lopez Jr.