Mahakasyapa

Again, Maha means great, many, and victorious. The Sanskrit word Kasyapa means “great turtle clan,”32 because Mahakasyapa’s ancestors saw the pattern on the back of a giant turtle and used it to cultivate the Way. Mahakasyapa or Kasyapa (Maha Kassapa): He was one of the foremost disciples of the Buddha and became the president of the First Great Council at Rajagrha held shortly after the Buddha's Parinirvana. He is considered the first ancestor in the Zen tradition as he was the only one who understood the Buddha's meaning when the Buddha held up a flower and smiled, saying nothing. This meant that Mahakasyapa understood that the truth is beyond words or doctrine and requires a direct transmission from teacher to disciple.

See; "disciples," "Theravada Lineage Chart," "Lineage Chart for Exoteric Mahayana Sects," "Kadampa Lineage Chart," "Shurangama Sutra."

Kasyapa also means, “light drinking clan,” because his body shone with a light which was so bright it seemed to “drink up” all other light.

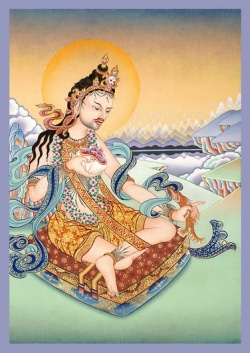

Why did his body shine? Seven Buddhas ago, in the time of the Buddha Vipasyin, there was a poor woman who decided to repair a ruined temple. The roof of the temple had been blown off and the images inside were exposed to the wind and rain. The woman went everywhere and asked for help, and when she had collected enough money she commissioned a goldsmith to regild the images. By the time he was finished, the goldsmith fell in love with her and said, “You have attained great merit from this work, but we should share it. You may supply the gold and I will furnish the labour, free.” So the temple was rebuilt and the images regilded. The goldsmith asked the woman to marry him and, in every life, for ninety-one kalpas, they were husband and wife and their bodies shone with purple and golden light.

Mahakasyapa was born in India, in Magadha. When he was twenty his father and mother wanted him to marry, but he said, ‘The woman I marry must shine with golden light. Unless you find such a woman, I won’t marry.” Eventually they found one, and they were married. As a result of their good karma their bodies shone with gold light and they cultivated together and investigated the doctrines of the Way. When Mahakasyapa left home to become a Bhikshu, his wife became a Bhikshuni called “Purple and Golden Light.”

Mahakasyapa’s personal name was “Pippala,” because his parents prayed to the spirit of a pippala tree to grant them a son. As the First Patriarch, Mahakasyapa holds an important position in Buddhism. When Shakyamuni Buddha spoke the Dharma, the Great Brahma Heaven King presented him with a golden lotus and Shakyamuni Buddha held up the flower before the assembly. At that time, hundreds of thousands of gods and men were present, but no one responded except Mahakasyapa, who simply smiled.

Then the Buddha said, “I have the Right Dharma- Eye Treasury. The wonderful Nirvanic mind, the Real Mark which is unmarked. This Dharma-door of mind to mind transmission has been transmitted to Kasyapa.” Thus Mahakasyapa received the transmission of Dharma and became the first Buddhist Patriarch. Venerable Mahakasyapa is still present in the world. When he left home under the Buddha he was already one hundred and sixty years old. By the time Shakyamuni Buddha had spoken Dharma for forty-nine years in over three hundred Dharma assemblies, Kasyapa was already over two hundred years old.

After Shakyamuni Buddha entered Nirvana, Kasyapa went to Southwestern China, to Chicken Foot Mountain in Yunnan Province. It has been over three thousand years since the Buddha’s Nirvana, but Mahakasyapa is still sitting in samadhi in Chicken Foot Mountain waiting for Maitreya Buddha to appear in the world. At that time he will give Maitreya the bowl which the Four Heavenly Kings gave Shakyamuni Buddha and which Shakyamuni Buddha gave him, and his work in this world will be finished. Many cultivators travel to Chicken Foot Mountain to worship the Patriarch Kasyapa, and on the mountain there are always three kinds of light: Buddha light, gold light, and silver light.

Those with sincere hearts can hear a big bell ringing inside the mountain. It rings by itself, and although you can’t see it, you can hear it for several hundred miles. It’s an inconceivable state. Mahakasyapa was the foremost of the Buddha’s disciples both in ascetic practices and in age. None of the Buddha’s disciples was older and none of them endured more suffering. The term “ascetic practice”34 means, “making an effort, raising up one’s spirits with courage and vigor.” The cultivation of the twelve kinds of ascetic practices is a sign that the Buddhadharma is being maintained, for as long as they are practiced, the Dharma will remain in the world. If they are not practiced, the Buddhadharma will disappear. Of the twelve ascetic practices, the first two deal with clothing:

1) Wearing rag-robes. One gathers unwanted cloth from garbage heaps, washes it, and sews it into a robe. There are many advantages in wearing rag-robes. First of all, they decrease greed. When you wear them, your heart is peaceful and calm. They also prevent others from being greedy. If you wear fine, expensive clothes, others may become envious and may even try to steal them. But no one wants to steal rag-robes. So the first ascetic practice benefits you and others.

Those who have left home are called “tattered sons” because they wear rag-robes. 2) Wearing only three robes. One’s only possessions are three robes, a bowl, and a sitting cloth. The first robe is the great robe, the samghati, made of 25 strips of cloth in 108 patches, which is worn when lecturing Sutras or visiting the king. The second is the outer robe, the uttarasanga, made of seven pieces, which is worn when bowing repentance ceremonies and worshipping the Buddha. The third is the inner robe in five pieces, the antarvasaka, which is worn at all times, to work in, to travel in, and to entertain guests. With 34. ku hang , duskara-carya only three robes, a bowl, and a sitting cloth, one teaches others to be content and not be greedy for a lot of possessions. 3) Always begging for food. One always takes one’s bowl to beg, and does not cook for oneself.

4) Begging in succession. One begs from house to house in regular order without discriminating between the rich and the poor. If, by the seventh house, no food is obtained, one doesn’t eat on that day. One doesn’t think, “I want to beg from the poor, not the rich,” or “I want to beg from the rich and not the poor.” Mahakasyapa once said, “Poor people are to be pitied. If they don’t plant blessings now, in the future they will be even poorer.” He begged exclusively from the poor.

Subhuti, on the other hand, begged only from the rich. “If they are rich,” he reasoned, “we should help them continue to plant blessings and meritorious virtue. If they don’t make offerings to the Triple Jewel, next life they’ll have no money,” and so he begged only from the rich.

But the Buddha scolded both of them. “You two have the hearts of Arhats,” he said, “because you discriminate in your begging.” To beg properly, one should go from house to house, without discrimination. 5) Eating only once in the middle of the day. This means that you do not eat in the morning or in the evening, but only between the hours of eleven and twelve o’clock in the morning. Some who don’t understand the Buddhadharma think that “eating once in the middle of the day” means simply eating only one lunch.

It actually means that one doesn’t eat in the morning or in the evening, but only once in the middle of the day. In China, when one receives the precepts, they ask, “Neng ch’ih?” which means “Can you keep them?” the preceptee answers, “Neng ch’ih!” which means “I can” If one eats in the morning, noon, and evening, however, one can answer “Neng ch’ih!” which sounds the same, but means “I can eat!”

Eating once a day at noon is one of the Buddha’s rules, because the Buddha only responded to offerings of food at noon. Gods eat in the morning, animals eat in the afternoon, and ghosts eat at night. Those who have left home do not eat at night because when ghosts come out at night to look for food and hear the sound of chopsticks they run to steal the food. The food the people are eating turns into fire in the ghosts’ mouths and they get angry and take revenge by making people sick.

6) Reducing the measure of what you eat. If you can eat three bowls, then eat only two and a half. If you can eat two bowls, then eat only one and a half. Always eat a little less. If you eat too much your stomach can’t hold it and you’ll have to do a lot of work on the toilet. Eat less.

7) Not drinking juices after noon. After twelve, you don’t drink apple juice, orange juice, milk, or any kind of juice at all, how much the less bean curd broth! True ascetics don’t drink juice after noon. Some people cultivate one or two of these practices and some cultivate more; some cultivate only one and some cultivate all twelve. It’s not fixed; it depends upon how strong you are. Since cultivators can’t avoid the questions of clothing, food, and dwelling, these twelve ascetic practices have been established to deal with them. The five which concern dwelling are: 8) Dwelling in an aranya. Aranya is a Sanskrit word which means “still and quiet place.” In an aranya, one is left alone and there are no distracting noises. It is said, What the eyes don’t see

won’t cause the mouth to water;

What the ears don’t hear

won’t cause the mind to transgress.

When people see food, they give rise to desire for it and their mouths water. If your ears don’t hear confusing sounds, there is no affliction in your mind. In a still, quiet place, it is easy to cultivate diligently and enter samadhi.

9) Dwelling at the foot of a tree. You live beneath a tree, but not under any one tree for more than three nights. After two nights, you move for fear that someone might come and make offerings to you. Cultivating ascetics don’t like to have such Dharma affinities or a lot of food and drink, and so they live under a tree.

10) Dwelling under the open sky. You don’t live in a house or even under a tree, but right out in the open, meditating. 11) Dwelling in a graveyard. Living here, one in always on the alert. “Look at them! They’re dead. In the future I’ll be just like them. If I don’t cultivate the Way, what will I do when it’s time to die? I’ll die all muddled.”

Dwelling in a graveyard is a good cure for laziness.

12) Ribs not touching the mat. This means always sitting and never lying down, cultivating vigorously and not fearing suffering. These are the five ascetic practices which deal with dwelling. Mahakasyapa cultivated not only one ascetic practice, but all twelve of them very thoroughly. Once, the Buddha moved over and asked him to sit beside him. The Buddha couldn’t bear to see him cultivating ascetic practices at his age. “Kasyapa,” he said, “you are over two hundred years old, too old for ascetic practices. Take it easy. You can’t endure them.”

The Venerable Kasyapa smiled. He didin’t say whether or not he would obey the Buddha’s instructions, but he returned and continued to practices just as before. The Buddha knew this and was extremely pleased. “Because, within my Dharma, Mahakasyapa cultivates ascetic practices,” the Dharma will remain long in the world. He’s a great asset, formost in asceticism.” The twelve ascetic practices are cultivated by those who have left the home-life.

“I haven’t left the home-life,” someone says. “Why are you explaining them to me?”

This seems like a good question, but if you look into it, it’s really irrelevant. Why? Perhaps you have not left home in this life, but how do you know that you did not leave home in a past life and cultivate these practices? Perhaps you have just forgotten, and so I am reminding you.

Even if you did not leave home in past lives, perhaps next life the opportunity will arise, and the Bodhi seeds planted in this life will mature. Then your merit and virtue will be perfected and you will feel very comfortable practicing asceticism. Because you heard about it in this life, next life you will enjoy cultivating it. Perhaps in the past you planted good causes, and now you reap the good fruit; or perhaps in this life you plant good causes, and in a future life will reap the good fruit.

No one can say that someone will always leave home, or that someone else will always be at home, or that someone will always be a common person. Common people all have the opportunity to realize Buddhahood. In the future these twelve ascetic practices will be of great use. Mahakatyayana Maha has been explained. Katyayana means “literary elegance,”36 because of all the Buddha’s disciples, this Venerable One was the foremost in debate. No one could defeat him. On one occasion a non-Buddhist who believed in annihilationism said,

“Buddhists speak of the revolving wheel of the six paths of rebirth and maintain that after death one may be reborn again as a person, but this principle is incorrect. Why? If people can come back as people, why hasn’t anyone ever died and then returned home, or sent a letter to his family? There’s no basis for such a view. When people die, they go out like a lamp and they can’t be born again. Buddhists imagine that there’s rebirth, but actually there is none.” Mahakatyayana replied, “You’ve asked why those who die do not return. Before I answer first let me ask you a question. If someone were put in jail for a crime, could he return home at his convenience?”

“No,” said the non-Buddhist, “of course not.” Katyayana continued, “When people descend to rebirth in the hells, it’s just the same and they can’t return; in fact, they are even less free to leave.”

The non-Buddhist said, “Granted that those born in the hells cannot return, still, those born in the heavens are very free. Why has none of them ever sent a letter home informing his family of his whereabouts?”

Katyayana said, “What you say has principle, but, by way of analogy, suppose someone slipped and fell into a toilet, not a flush toilet—obviously no one could fall into a flush toilet—but into a pit toilet about as big as a bedroom. Once he got out, would he decide he liked the aroma there and jump back in again?” “Heavens no,” exclaimed the non-Buddhist. “The world of men,” said Katyayana, “is just like a toilet, and birth in the heavens is like getting out.

That’s why no one comes back. Even if they did, there’s the time difference to consider. For example, one day and night in the Heaven of the Thirty-Three is equal to one hundred years in the world of men. Born there, it would take a couple of days to find a place to stay and get settled, and by the time one returned on the third day, one’s friends would have long been dead.”

Thus, Mahakatyayana’s eloquence defeated non-Buddhists who were attached to the idea of annihilation or permanence; they lost every time.

Katyayana’s name also means “fan cord.”37 Soon after he was born his father died and his mother wanted to remarry, but the child was a tie, like a fan cord, which prevented her from doing so. He is also called “good shoulders”38 because his shoulders were beautiful, and “victorious thinker”39 because his eloquence was unobstructed.

There are four kinds of unobstructed eloquence: 1) With “unobstructed eloquence in Dharma” one can explain the Dharma without obstacle.

2) With “unobstructed eloquence in meaning” one can explain the Dharma’s limitless meanings. 3) With “unobstructed eloquence in phrasing” one’s rhetoric is effective.

4) With “the eloquence of unobstructed delight in speech” one takes delight in explaining the Dharma. Because he had these four kinds of unobstructed eloquence, Mahakatyayana was the foremost of the Buddha’s disciples in debate.