Buddhist Way to a Harmonious Society: The Four Sublime States of Mind

Buddhist Way to a Harmonious Society: The Four Sublime States of Mind

Dr. Guang Xing

1. Introduction

The Pali word for the four sublime states is Brahma-vihara, which can be rendered as excellent, lofty or sublime states of mind; or alternatively, Brahma-like, god-like or divine abodes.

In Chinese translation there are two renderings: which is a direct translation from the original word: Brahma-vihara. The other is which is a rendered from its meaning, the four immeasurable or boundless states of mind.

The four sublime states or immeasurable or boundless states of mind are found in the Tevijja Sutta (D, I, 250), the Mahasudassana Sutta (D, ii, 186-7) and the Sanglti Sutta (D, iii, 220) of the Dighanikaya:

Brahmavihara (Divine abodes; sublime states). See also Metta; Karuna; Mudita; Upekkha . o Systematic cultivation of Brahmavihara: SN 42.8, AN 10.208

Practice of Brahmavihara as a door to the Deathless: MN 52, AN 11.17 Offering comfort and protection from the cold: Thag 6.2 Five realizations that arise from concentration based on the Brahmavihara: AN 5.27 Practicing any one of the Brahmavihara can take one all the way to fourth jhana: AN 8.63

The four sublime states are

1) Love or Loving-kindness (Pali: metta, Skt: maitrlM.) which seeks to overcome the human vice of anger;

2) Compassion (Pali & Skt: karuna M) which seeks to overcome the vice of cruelty;

3) Appreciative Joy (Pali & Skt: mudita #) which seeks to overcome the vice of jealousy and

4) Equanimity or impartiality (Pali: upekkha, Skt: upeksa }£) which seeks to overcome the vice of prejudice.

The term Brahma vihara

The four sublimes states (Brahma-vihara) are NOT compatible with a state of mind full of hate. They are akin to Brahma, the divine, the transient ruler of the higher heavens in the traditional Buddhist picture of the universe.

In contrast to many other conceptions of deities, East and West, who by their own devotees are said to show anger, wrath, jealousy and "righteous indignation," Brahma is free from hate; and one who assiduously develops these four sublime states, by conduct and meditation, is said to become an equal of Brahma [brahma-samo).

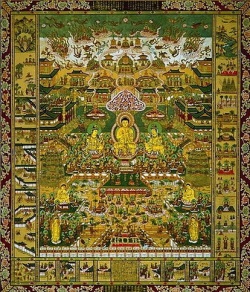

If these four states become the dominant influence in one's mind, one will be reborn in congenial worlds, the realms of Brahma. Therefore, these states of mind are called God-iike, Brahma-iike. (Show the heavenly world)

They are called abodes (vihara) because they should become the mind's constant dwelling-places where we feel "at home"; they should not remain merely places of rare and short visits, soon forgotten. In other words, our minds should become thoroughly saturated by them.

They should become our inseparable companions, and we should be mindful of them in all our common activities. As the Metta Sutta, the Song of Loving-kindness, says:

When standing, walking, sitting, lying down, Whenever he feels free of tiredness Let him establish well this mindfulness - This, it is said, is the Divine Abode.

Another meaning of Brahmavihara: boundless

These four ~ love, compassion, appreciative joy and equanimity - are also known as the boundless states (appamahha), because, in their perfection and their true nature, they should not be narrowed by any limitation as to the range of beings towards whom they are extended.

They should be non-exclusive and impartial, not bound by selective preferences or prejudices. A mind that has attained to that boundlessness of the Brahma-viharas will not harbor any national, racial, religious or class hatred.

But unless rooted in a strong natural affinity with such a mental attitude, it will certainly not be easy for us to effect that boundless application by a deliberate effort of will and to avoid consistently any kind or degree of partiality.

Meditation on the four sublime states

To achieve the above mentioned aim, in most cases, we shall have to use these four qualities not only as principles of conduct and objects of reflection, but also as subjects of methodical meditation.

That meditation is called Brahma-vihara-bhavana, the meditative development of the sublime states. The practical aim is to achieve, with the help of these sublime states, those high stages of mental concentration called jhana, "meditative absorption."

The meditations on love, compassion and appreciative joy may each produce the attainment of the first three absorptions, namely the first, second and third jhana or dhyana, while the meditation on equanimity will lead to the fourth jhana only, in which equanimity is the most significant factor.

Generally speaking, persistent meditative practice will have two crowning effects: first, it will make these four qualities sink deep into the heart so that they become spontaneous attitudes not easily overthrown; second, it will bring out and secure their boundless extension, the unfolding of their all- embracing range, (like driving)

In fact, the detailed instructions given in the Buddhist scriptures for the practice of these four meditations are clearly intended to unfold gradually the boundlessness of the sublime states. They systematically break down all barriers restricting their application to particular individuals or places.

The purpose

The Buddha advised Rahula thus:

1. "Rahula, practice loving kindness to overcome anger. Loving kindness has the capacity to bring happiness to others without demanding anything in return.

2. Practice compassion to overcome cruelty. Compassion has the capacity to remove the suffering of others without expecting anything in return.

3. Practice appreciative joy to overcome hatred. Sympathetic joy arises when one rejoices over the happiness of others and wishes others well-being and success.

4. Practice equanimity to overcome prejudice.

Non-attachment is the way of looking at all things openly and equally.

This is because that is. Myself and others are not separate. Do not reject one thing only to chase after another.

I call these the four immeasurables. Practice them and you will become a refreshing source of

vitality and happiness for others." The four vices of anger, cruelty, hatred and prejudice are responsible for most of social crimes and injustice, but they cannot be prevented by law or precepts unless they manifest through body of mouth.

These four attitudes of mind are said to be excellent or sublime because they are the right or ideal way of conduct towards living beings. They provide, in fact, the answer to all situations arising from social contact.

According to Buddhism, they are (1) the great removers of tension, (2) the great peace-makers in social conflict, and (3) the great healers of wounds suffered in the struggle of existence.

On the positive aspects, (1) they level social barriers, (2) build harmonious communities, (3) awaken slumbering magnanimity long forgotten, (4) revive joy and hope long abandoned, and (5) promote human brotherhood against the forces of egotism. (Nyayaponika)

The philosophy behind the four sublime states is that all human beings are taken on equal level and none is regarded as evil in nature. There is no original sin as understood by other religions so human beings are not born evil, they committed bad actions due to their ignorance. Therefore, we should not look at our enemies with any hostile eye.

So the purpose of practicing such meditation and cultivation is to eliminate the bad states of mind such as anger, cruelty, hatred and prejudice, because these unwholesome mentalities bring us unhappiness and suffering.

Everyone wants to be happy, but happiness cannot be achieved in isolation. One's happiness depends upon the happiness of all and the happiness of all depends upon the happiness of one. This is because all life is interdependent. In order to be happy, one needs to cultivate wholesome attitudes towards others in society and towards all sentient beings.

"Hatred never ceases through hatred in t his world; through non-hatred alone they cease. This is an eternal law." Dhammapada verse No.5.

The entire Buddhist social philosophy rests on this principle that the causes to all social problems can be traced to human mind and the solution to it is to train our to with these four boundless qualities.

2. Love or Loving-kindness (Pali: metta, Skt: maitri ) %

The best definition of the Sublime State of Metta is given in the following sutta. Metta Sutta

1. Whatever is to be done by one who is skilful in seeking (what is) good, having attained that tranquil state (of Nibbana):-Let him be able and upright and conscientious and of soft speech, gentle, not proud, (142)

2. And contented and easily supported and having few cares, unburdened and with his senses calmed and wise, not arrogant, without (showing) greediness (when going his round) in families. (143)

3. And let him not do anything mean for which others who are wise might reprove (him); may all beings be happy and secure, may they be happy-minded. (144)

4. Whatever living beings there are, either feeble or strong, all either long or great, middle- sized, short, small or large, (145)

5. Either seen or which are not seen, and which live far (or) near, either born or seeking birth, may all creatures be happy-minded. (146)

6. Let no one deceive another, let him not despise (another) in any place, let him not out of anger or resentment wish harm to another. (147)

7. As a mother at the risk of her life watches over her own child, her only child, so also let every one cultivate a boundless (friendly) mind towards all beings. (148)

8. And let him cultivate goodwill towards all the world, a boundless (friendly) mind, above and below and across, unobstructed, without hatred, without enmity. (149)

9. Standing, walking or sitting or lying, as long as he be awake, let him devote himself to this mind; this (way of) living they say is the best in this world. (150)

10. He who, not having embraced (philosophical) views, is virtuous, endowed with (perfect) vision, after subduing greediness for sensual pleasures, will never again go to a mother's womb. (151)

The Suttanipada, tr. V. Fausboll

You can download the English translation of the entire Dhammapada and Suttanipada from this website:

http://www.sacred-texts.com/bud/sbelO/index.htm

Nyanaponika Thera summarizes the sutta beautifully:

Love, without desire to possess, knowing well that in the ultimate sense there is no possession and no possessor: this is the highest love.

Love, without speaking and thinking of "I," knowing well that this so-called "I" is a mere delusion.

Love, without selecting and excluding, knowing well that to do so means to create love's own contrasts: dislike, aversion and hatred.

Love, embracing impartially all sentient beings, just as the sun sheds its rays on all without any distinction, and not only those who are useful, pleasing or amusing to us. Love, embracing all beings of all sizes and distance: small and great, far and near, be it on earth, in the water or in the air.

Love, embracing all beings of different mentality, be they noble-minded or low-minded, good

or evil. The noble and the good are embraced because love is flowing to them spontaneously.

The low-minded and evil-minded are included because they are those who are most in need

of love. In many of them the seed of goodness may have died merely because warmth was

lacking for its growth, because it perished from cold in a loveless world.

Love, embracing all beings, knowing well that we all are fellow wayfarers through this round

of existence - that we all are overcome by the same law of suffering.

Love, but not the sensuous fire that burns, scorches and tortures, that inflicts more wounds

than it cures - flaring up now, at the next moment being extinguished, leaving behind more

coldness and loneliness than was felt before.

Highest love is to show to the world the path leading to the end of suffering, the path pointed out, trodden, and realized to perfection by Him, the Exalted One, the Buddha.

Meditation on Metta

In the Visuddhimagga, detailed method of meditation on metta is recommended. The meditator should first go to some quiet place, where one can sit down in a comfortable position.

Then, before starting the actual meditation, it is helpful to consider the dangers in hate and the benefits offered by forbearance: for it is a purpose of this meditation to displace hate by forbearance, and besides, one cannot avoid dangers one has not come to see or cultivate benefits one does not yet know.

Then there are certain types of persons towards whom loving-kindness should not be developed in the first stages.

(1) One should not start metta meditation towards a disliked person for one will soon get fatigue.

(2) One should also not try to regard a dearly loved friend with neutrality, if so one will soon get fatigue.

(3) One should not start it with an indifferent person for if an indifferent person is put into a dear one's place, the meditator will get fatigue too.

(4) One should not do metta meditation towards an enemy since anger will spring up.

(5) Again it should not be directed towards members of the opposite sex, to begin with, for this may arouse lust.

(6) One should not start with a dead person for loving-kindness will not spring up.

Develop

(1) Instead, one should first start metta meditation towards oneself and repeat the following words in this way: "May I be happy and free from suffering" or "May I keep myself free from hostility and trouble and live happily".

It is because only when you are full of the thought of loving-kindness and your mind is pervaded with metta, then you start the second step. (Just like a lamp)

(2) You should extend this loving thought to one's liked, admired and respected ones. So one should first become familiar with pervading oneself as example with loving-kindness.

The Visuddhimagga gives the example of a teacher, but you can start with your parents. The meditation can then be developed towards him, remembering endearing words or virtues of his, and thinking such thoughts about him as "may he be happy, may she be happy may my parents be happy."

When this has become familiar, one can begin to practice loving-kindness towards a dearly beloved companion.

(3) When the above is done, then one should meditate towards a neutral person taking him or her as a very dear one. This requires strong mental strength.

(4) The last step is to meditate towards an enemy as neutral. This is only for those who really has an enemy. This is a very difficult way because when dealing with an enemy that anger can arise, and all means must be tried in order to get rid of it.

The Visuddhimagga describes many ways to overcome this difficulty.

(1) First the meditator should enter repeatedly into loving kindness towards the first mention persons directing metta towards that person.

(2) If not, then the meditator should think the Buddha's words, the teaching.

(3) Think of the enemy's good qualities, the past association you had with him or her. (the present enemy is your past friend)

(4) Then change your position with your enemy and suppose you were hurt.

(5) Then you observe your own karma and the karma of your enemy.

(6) Think of the Buddha before he got enlightened he had enemies but he forgave them all.

(7) Observe the long samsara and in this stream the enemy may once be a relative of yours.

(8) Think of the benefits of metta meditation.

(9) Think that the enemy is made of five aggregates the same as you.

(10) The last is to give a gift to your enemy.

As soon as this has succeeded, one will be able to regard an enemy without resentment and with loving-kindness in the same way as one does the admired person, the dearly loved friend, and the neutral person.

Then with repeated practice, jhana absorption should be attained in all cases. Loving-kindness can now be effectively maintained in being towards all beings; or to certain groups of beings at a time, or in one direction at a time to all; or to certain groups in succession.

By such a way, one breaks the barriers. Loving-kindness ought to be brought to the point where there are no longer any barriers set between persons, and for this the following example is given in the Visuddhimagga:

Suppose a man is with a dear, a neutral and a hostile person, himself being the fourth; then bandits come to him and say "we need one of you for human sacrifice."

Now if that man thinks "Let then take this one, or that one," he has not yet broken down the barriers, and also if he thinks "Let them take me but not these three," he has not broken down the barriers either.

Why not? Because he seeks the harm of him who he wishes to be taken and the welfare of only the other three.

It is only when he does not see a single one among the four to be chosen in preference to the other three, and directs his mind quite impartially towards himself and the other three, that he has broken down the barriers.

In many discourses the Buddha lays emphasis on the need to balance contemplative concentration with understanding.

Concentration alone lacks direction; understanding alone is dry and tiring. In the discourses that follow the simile of a mother's love for her child is given.

Now the incomparable value of a mother's love, which sets it above all other kinds, lies in the fact that she understands her child's welfare -- her love is not blind. Not love alone, nor faith alone, can ever bring a man all the way to the cessation of suffering, and that is why the Buddha, as the Supreme Physician, prescribes the development of five faculties in balanced harmony: the faculties of faith, energy, mindfulness, concentration and understanding.

Then the meditator should extends his thought of loving-kindness towards one direction and thinking May all beings be well and happy. Then to the other directions and at last to the ten directions for all sentient beings.

Benefits of Metta Meditation

The Theravada commentator Buddhaghosa said that there are eleven benefits of practicing metta meditation:

1) . He who practises metta sleeps happily. As he goes to sleep with a light heart free from hatred he naturally falls asleep at once. This fact is clearly demonstrated by those who are full of loving-kindness. They are fast asleep immediately on closing their eyes.

2) . As he goes to sleep with a loving heart he awakes with an equally loving heart. Benevolent and compassionate persons often rise from bed with smiling faces.

3) . Even in sleep loving persons are not perturbed by bad dreams. As they are full of love during their waking hours, they are peaceful in their sleeping hours too. Either they fall into deep sleep or have pleasant dreams.

4) . He becomes dear to human beings. As he loves others, so do others love him. The outside world reacts on one in the same way that one acts towards the world. One full of faults himself is apt to see the evil in others. The good he ignores.

5) . He who practises metta is dear to non-humans as well. Animals are also attracted to him. Radiating their loving-kindness, ascetics live in wild forests amidst ferocious beasts without being harmed by them. (Elephant example)

6) . Owing to his power of metta he becomes immune from poison and so forth unless he is subject to some inexorable Kamma.

7) . Invisible deities protect him because of the power of his metta.

8) . Metta leads to quick mental concentration. As the mind is not perturbed by hostile vibrations one-pointedness can be gained with ease. With mind at peace he will live in a heaven of his own creation. Even those who come in contact with him will also experience that bliss.

9) . Metta tends to beautify one's facial expression. The face as a rule reflects the state of the mind. When one gets angry, the heart pumps blood twice or three times faster than the normal rate. Heated blood rushes up to the face, which then turns red or black. At times the face becomes repulsive to sight. Loving thoughts on the contrary, gladden the heart and clarify the blood. The face then presents a lovable appearance.

It is stated that when the Buddha, after Enlightenment, reflected on the Causal Relations (Patthana), His heart was so pacified and His blood so clarified that rays of different hue such as blue, yellow, red, white, orange, and a mixture of these emanated from His body.

10) . A person imbued with metta dies peacefully as he harbours no thoughts of hatred towards any. Even after death his serene face reflects his peaceful death.

11) . Since a person with metta dies happily, he will subsequently be born in a blissful state. If he has gained the Jhanas (ecstasies), he will be born in a Brahma realm.

Mahayana Development

On the basis of early Buddhism, Mahayana developed the concept of metta further into three categories:

(1) metta of sentient being,

(2) metta on account of dharm,

(3) metta without any condition.

This is found in the Mahaprajhaparamita sastra X^SM fascicle 33.

The first one: metta of sentient beings means that this loving-kindness can be found in sentient beings and those who are still at the stage of learning such as sravakas (the first three stages on the way to liberation).

It is directed towards sentient beings and takes them as loved ones.

The second one: metta on account of dharma fell is found in arhants and pratyeka Buddhas since they know the emptiness of both Dharma and Self.

They have eliminated the difference between oneself and others, but looked forward to save sentient beings who do not understand the emptiness of Dharma.

Therefore, they extend their loving-kindness to sentient beings and save them. This is similar to the last stage when barriers are broke.

The third one: metta without conditions *£f is only found in Buddhas.

The enlightened ones do not abide in either conditioned or unconditioned dharmas, nor in past, present and future, but they know well the reality of the world so they do not abide in anywhere.

However, Buddhas know that sentient beings do not realize the reality of the world so they are wondering in samsara.

Their minds attach to various things. So Buddhas rise the mind to save them. Compared the last one with the former two, the metta of Buddhas is great and the other two kinds of metta are small.

So the loving-kindness of Buddhas is named Great Loving-kindness without conditions. MMXM

This development is perhaps based on Sarvastivada teaching which will be discussed in the following section.

3. Compassion (Pali & Skt: karuna)

Compassion, the second of the sublime states, is a cardinal principle in Buddhism no matter Theravada, Mahayana or Tantrayana.

Compassion or Karuna is the wish for all sentient beings to be free from suffering. It counters cruelty. The following are some definitions given by modern writers:

"It is defined as that which makes the heart of the good quiver when others are subject to suffering, or that which dissipates the suffering of others." (Narada, The Buddha and His Teachings (BPS, 1988), p.372)

"Compassion is a virtue which uproots the wish to harm others. It makes people so sensitive to the sufferings of others and causes them to make these sufferings so much their own that they do not want to further increase them." (Edward Conze, Buddhist Thought in India, 1960, Ch.6)

"This (compassion) isn't self-pity or pity for others. It's really feeling one's own pain and recognizing the pain of others. Seeing the web of suffering we're all entangled in, we become kind and compassionate to one another." (Joseph Goldstein, The Experience of Insight (BPS, 1980), pp.125-26)

The above definitions vary. Yet central to all is the claim that karuna concerns our attitude to the suffering of others. In the Buddhist texts the term often refers to an attitude of mind to be radiated in meditation. This is usually considered its primary usage.

The meaning of karuna

In fact, at least three strands of meaning in the term "compassion" can be detected in the texts as reported by Elizabeth J. Harris: (

1) a prerequisite for a just and harmonious society,

(2) an essential attitude for progress aiong the path towards wisdom {pahha); and

(3) the iiberative action within society of those who have become enlightened or who are sincerely following the path towards it.

For the first meaning, Buddhism has the five precepts which are for all: no killing, no stealing, no adultery, no false speech and no alcohol.

This, actually, is the foundation for any spiritual progress within Buddhism.

Compassion for the life, feelings, and security of others is inseparably linked with the first, second, and fourth precepts.

1. 1 undertake the rule of training to refrain from injury to living things.

2. 1 undertake the rule of training to refrain from taking what is not given.

3. 1 undertake the rule of training to refrain from false speech. The first precept must flow from compassion if it is to be effective. The Vasala Sutta of the Suttanipada makes this relationship explicit, although the word daya, usually translated as sympathy or compassion, is used and not karuna:

"Whoever in this world harms living beings, once-born or twice-born, in whom there is no compassion for living beings-know him as an outcast." (Suttanipada, 117) In China, monks practice vegetarian food out of compassion not to eat the flesh of animals.

Important to the exercising of this kind of compassion is the realization that life is dear to all, as shown in the following Dhammapada verse:

"All tremble at violence Life is dear to all

Putting oneself in the place of another

One should neither kill nor cause another to kill." (Dhp. V. 130) Here, non-harming and compassion flow both from a sensitivity to our own hopes and fears and the ability to place ourselves in the shoes of others.

Compassion towards self and compassion towards others are inseparable.

In the Suttanipada, it is advised to compare oneself with others in such terms as "Just as I am so are they, just as they are so am I", one should neither kill nor cause others to kill. (Sn. v. 705)

The second meaning of compassion: an essential attitude for progress along the path towards wisdom (pahha).

To the second meaning, the word "karuna" was most often mentioned in the texts in the specialized context of meditation to denote an important form of mind training. Here the emphasis is on each person's pilgrimage towards Nibbana rather than on interaction with other beings.

In the spiritual progress, moral uprightness is stressed initially but the final stages of the path are seen purely in terms of meditation and mind-training. At this point, no mention is made of outgoing action:

"By getting rid of the taint of ill-will, he lives benevolent in mind; and compassionate for the welfare of all creatures and beings, he purifies the mind of the taint of ill-will." (M. I. p.347)

In this context, the development of karuna plays an essential part in the meditation practice that leads towards wisdom (pahha) and the destruction of craving.

The importance of this must not be underestimated. The development of a compassionate mind is a direct preparation for right concentration (samma samadhi) and a prerequisite of Nibbana.

In the Majjhimanikaya, it says: "If from a brahman's family, if from a merchant's family, if from a worker's family, and if from whatever family he has gone forth from home into homelessness and has come into this dhamma and discipline taught by the Tathagata, having thus developed friendliness (mettd), compassion (karuna), appreciative joy (mudita), and equanimity (upekkha), he attains inward calm, say it is by inward calm that he is following the practices suitable for recluses." (M 1 284)

The higher stages are seen to rest on them because they have the power to weaken the defilements of lust, ill-will, and delusion and to bring the mind to a state of peace. Rarely is meditation mentioned without reference to them.

The third meaning of compassion: the liberative action within society of those who have become enlightened or who are sincerely following the path towards it.

It is compassion that the Buddha, after enlightenment, not only remained in but went into society to teach other suffering beings to get release.

It is also through compassion that the Buddha told his disciples to go out and spread his message to liberate people from pain.

In his commentary to the Visuddhimagga, Acariya Dhammapala speaks about the great compassion (mahakaruna) and wisdom (pahha) of the Buddha. The passage is structured in a series of parallel sentences, each one contrasting and comparing the fruits of the two qualities.

The following are selected from the longer whole:

"It is through understanding (wisdom) that he fully understood others' suffering and through compassion that he undertook to counteract it.

It was through understanding that he himself crossed over and through compassion that he brought others across." "Likewise it was through compassion that he became the world's helper and through understanding that he became his own helper."

In the above passage, pahha or wisdom is connected with knowledge and insight, and karuna or

compassion with liberative action

For forty-five years, the Buddha preached in the face of numerous problems such as criticism, opposition, and misunderstanding, in the knowledge that the Dhamma would be understood only by a few.

This is vividly illustrated in the traditional stories of his encounters with Devadatta, Patacara, the destitute Kisagotami, the murderer, Angulimala out of compassion.

This ideal was placed before the whole monastic Sangha. Although many members of the Sangha may have failed to reach it, it is certain that some attained a stage where compassionate, loving action had replaced selfishness. The mission he set for himself and for the Sangha was one of compassionate, liberative action. The first sixty arahants were sent out with the words:

"Go forth, bhikkhus, for the good of the many, for the happiness of the many, out of compassion for the world, for the good, benefit, and happiness of gods and men. Let not two go by the same way." (Vin 1 20)

Sarvastivada development: The Great Compassion {Mahakaruna)

The term 'great compassion' (mahakaruna) was most probably first introduced by the Sarvastivadins so that the compassion of the Buddha could be distinguished from ordinary compassion since, we do not find the term Great Compassion in early Buddhism.

The *Abhidharmakosabhasya (Kosa) of Vasubandhu speaks of five reasons as to why the compassion of the Buddha is termed 'great compassion', but both the *Abhidharma(pitaka)prakaranasasanasastra and the *Abhidharmanyayanusarasastra of Sahghabhadra list four more reasons in addition to the five standard reasons given in the former text by other Sarvastivada teachers. 1

However, Sahghabhuti's translation of the Vibhasa, which is the earliest, gives seven reasons, while Buddhavarma's translation, which is the second, and Xuanzang's translation, which is the latest and longest, give nine similar reasons. 2

Differences between great compassion and ordinary compassion

Compassion (karuna) is amply present in many places in the early sutras, and the Buddha is described as one who is fully accomplished in both wisdom and compassion.

1 The Kosa, T29, 0141a; another translation of the Kosa-bhasya, T29, 292a; the *Abhidharma(pitaka)prakaranasasanasastra, T29, 957b; and the *Abhidharmanyayanusarasastra, T29, 749b.

2 Sahghabhuti's translation of the Vibhasa, T28, 496b-c; Xuanzang's translation of the Vibhasa, 121, 159b-160a. The reasons given in Buddhavarma's translation are very much the same as that of Xuanzang's translation.

However, the Sarvastivadins distinguished the compassion of the Buddha from ordinary compassion and named it 'great compassion'. They further explained that the great compassion differs from ordinary compassion in eight ways.

In the Abhidharmakosabhdsya (T27, 160b), we find this:

(1) With respect to its nature, ordinary compassion is absence of hatred, whereas great compassion is absence of ignorance.

(2) With respect to its scope, ordinary compassion takes the form of ordinary suffering, whereas great compassion takes on the form of a threefold suffering, (ordinary suffering, suffering produced by change and suffering caused by five aggregates)

(3) With respect to its object, ordinary compassion is concerned with the beings of the kamadhatu only, whereas great compassion is concerned with beings of the three dhatus.

(4) With respect to its level (bhumi), ordinary compassion is on the level of the ten dhydnas: the four dhydnas, the four stages above the four dhydnas, antaradhydna and the kdmabhumi, whereas great compassion is of the level of the fourth dhydna only.

(5) With respect to its support, ordinary compassion arises in srdvakas, pratyekabuddhas, Buddhas as well as ordinary people (prthagjana), whereas great compassion arises only in Buddhas.

(6) With respect to its acquisition, ordinary compassion is obtained through detachment from the kamadhatu and the third dhydna, whereas great compassion is obtained through detachment from the bhavdgra only. (Here bhavdgra is the same as [[akanis ha heaven

^ or WJIK, the highest in the world of form)

(7) With respect to saving (others), ordinary compassion arouses only sympathy for the act of liberating (others), whereas great compassion not only gives rise to sympathy but also accomplishes the act of liberating.

(8) With respect to compassion, ordinary compassion is a partial of compassion, for it sympathizes only with beings who are suffering, whereas great compassion is turned toward all beings equally.

Characteristics of great compassion

According to both the Kosa and the Vibhdsd, great compassion is found in the fourth dhydna in the rupadhdtu and arises depending on the body of a great man mahdpurusa).

Here mahdpurusa or a great man means an Enlightened One. While still in Jambudvipa and thus in the kamadhatu, it is not conjoined with samddhi

(1) It accounts for all dharmas of the past, present, future; the good, the bad, and the neutral as well as all sentient beings in the three dhatus. (2) It does not include however the sixteen aspects of the four noble truths.

It is neither the no longer Learning saiksa) nor the Learning asaiksa) and accounts for neither saiksa nor asaiksa. Rather it is of the path of contemplation of the Dharma and of the worldly wisdom samvrtijhdna). It is obtained either by making great effort (prayoga) or when the defilements kiesas) are eradicated.

The great compassion is mentioned in the eighteen unique qualities of the Buddha according to the Sarvastivadins, but they do not mention other three factors of the four sublimes states.

Therefore, a question arises in the Vibhasa as to why it only speaks of great compassion, and not of great loving-kindness [mahamaitri), great joy [mahamudita) and great equanimity [mahopeksa). The Sarvastivadins explain that all the four should be spoken of as 'great' because (1) the merit of the Buddha is great, (2) it arises for the benefit and protection of sentient beings, (3) it arises out of his compassion towards sentient beings, and (4) it operates with a pure mind, equally and continuously directed towards sentient beings.

Mahayana development of the concept of compassion

In Mahayana Buddhism, the ideal of compassion has been developed further on the basis of the Sarvastivadins and is given much emphasis with bodhisattva ideal.

Bodhisattvas are aspired to become enlightened in order to liberate sentient beings in contrast to arhants whose aim is to become liberated for themselves first. This bodhisattva inspiration is out of compassion for all suffering beings because it is an enlightened one, a Buddha who can serve the sentient beings more than an arhant.

In early Buddhism, bodhisattva was seen as a rare figure who, by a longer and more compassion- oriented route than that leading to arahatship, sought to become eventually a full and perfect Buddha.

Such a Buddha, such as Maitreya, is one who brings benefit to countless beings by immense insight which rediscovers liberating truth when it had been lost after being taught by another Buddha, Sakyamuni for example, many thousands of years previously.

While in Mahayana all followers are encouraged to follow the bodhisattva path and compassion is the driving force. It is in this respect that the Mahayanists sometimes criticised sravakas as concerned only for their own liberation, rather an unfair criticism.

Theravada also acknowledges that aiming to liberate all beings is more perfect and virtues than working only for one's own deliverance. However, while the teaching still remains in the world only a few need to take this path for the benefit of future generations.

But Mahayana emphasized that in the vast universe there is always a need for more Buddhas to teach. The spirit of Mahayana compassion, the root of motivation of the bodhisattva, is well expressed in the vows of Amitabha Buddha.

Amitabha Buddha's vows

Amitabha Buddha is one of the earliest Mahayana Buddhas appeared and he made 24 or 48 vows before he attained Buddhahood. These vows show the compassion of the bodhisattva. Traditionally the 18th, 19th and 20th vows are considered to be the important ones.

(18) If, when I attain Buddhahood, sentient beings in the lands of the ten quarters who sincerely and joyfully entrust themselves to me, desire to be born in my land, and call my Name, even ten times, should not be born there, may I not attain perfect Enlightenment.

Excluded, however, are those who commit the five gravest offences and abuse the right Dharma.

(19) If, when I attain Buddhahood, sentient beings in the lands of the ten quarters, who awaken aspiration for Enlightenment, do various meritorious deeds and sincerely desire to be born in my land, should not, at their death, see me appear before them surrounded by a multitude of sages, may I not attain perfect Enlightenment.

(20) If, when I attain Buddhahood, sentient beings in the lands of the ten quarters who, having heard my Name, concentrate their thoughts on my land, plant roots of virtue, and sincerely transfer their merits towards my land with a desire to be born there, should not eventually fulfil their aspiration, may I not attain perfect Enlightenment.

In the same way, Bodhisattva Kshitigarbha made even greater vows to save all beings in hell in the past. So he is known as having said: "If I do not go to hell to help them, who else will go?"

No matter what the crime or the karma, Bodhisattva Kshitigarbha is willing to have a connection with any being, and to help free them from suffering.

The name of Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara even symbolizes compassion. It means "the lord who looks down upon the world to save those suffering beings". In the twenty fifth chapter of the Lotus Sutra, it is said that Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara would change himself into thirty two different forms in order to save suffering beings.

In Buddhist art, Avalokiteshvara is sometimes represented with one head and four or eighteen arms. Sometimes, he is shown with one thousand eyes and a thousand arms. In China, Avalokiteshvara is represented in female form and is known by the name Guan-yin.

All these are symbolize the great compassion of the Bodhisattva. It is because of this great compassion, so Avalokitesvara became the most popular Bodhisattva in East Asia.

Great compassion and great loving-kindness

As we have seen above, the concepts of metta or loving-kindness and karuna or compassion are quite similar. Then why they are named "great"?

The Mahayanists single out both compassion and loving-kindness from the four sublime states as a result of bodhisattva practices. Bodhisattvas, out of great compassion and great loving-kindness to save suffering beings, aspired to attain Buddhahood.

It is also because of great compassion, that bodhisattvas postpone their attainment to nirvana and stay in samsdra to save sentient beings. Therefore, great compassion is the foundation of Buddhism according to Mahayana Buddhism.

According to the Mahdprajhdparamitd sastra, (1) the compassion discussed in four sublimes states is small and the compassion discussed in the eighteen special qualities of the Buddha is great.

(2) The compassion of the Buddha is great and ordinary people's compassion is small. While the compassion of bodhisattvas are just smaller than that of the Buddhas.

This is because Buddhas have great virtues and merits.

4. Appreciative Joy (Pali & Skt: mudita) g

The term mudita has been translated variously as 'appreciative joy', 'sympathetic joy', 'altruistic joy', 'congratulatory and benevolent attitude' etc., but I like to use the first one: appreciative joy.

Appreciative joy, as the third of the four sublime states, is the wholesome attitude of rejoicing in the happiness and virtues of all sentient beings. It counters jealousy and makes people less self-centred.

Very often some people cannot bear to see the successful achievements of others. They rejoice over their failures but cannot tolerate their successes. Instead of praising and congratulating the successful, they try to ruin, condemn and vilify them.

Thus, it has two bad effects: first it creates a bad relationship between you and those who are successful; second it creates a bad mentality within you and makes you suffer rather than joy.

Thus, in one way mudita is concerned more with oneself to have a healthy mind than with others as it tends to eradicate jealousy which ruins oneself. On the other hand it aids others as well since one who practises mudita will not try to hinder the progress and welfare of others.

Jealousy is one of the causes to raise tension in human relation which sometimes result in conflict.

As Narada Thera says: "It is quite easy to rejoice over the success of one's near and dear ones, but rather difficult to do so over the success of one's adversaries.

Yes, the majority not only find it difficult but also do not and cannot rejoice. They seek delight in creating every possible obstacle so as to ruin their adversaries. They even go to the extent of poisoning, crucifying, and assassinating the good and the virtuous. Socrates was poisoned, Christ was crucified, Gandhi was shot. Such is the nature of the wicked and deluded world."

But at the same time, people also experience the kind of appreciative joy when they see the success of their loved ones and relatives. Just as a mother rejoices at her children's success and happiness in life.

These are the commonly experienced forms of appreciative joy.

The Buddhist practice of appreciative joy is to extend it to all sentient beings and not just to loved ones only through meditation, one then experiences appreciative joy as a sublime state of mind and as an immeasurable.

Samuel Goldman says: "When someone does something good, applaud! You will make two people happy."

5. Equanimity or impartiality (Pali: upekkha, Skt: upeksa) J£

Equanimity is a perfect, unshakable balance of mind, even-mindedness, rooted in insight. It is the attitude to look at all sentient beings as equals, irrespective of their present relationship to oneself. The wholesome attitude of equanimity counters attachment, clinging and aversion.

According to Buddhism, the world continually moves between contrasts: rise and fall, success and failure, loss and gain, honor and blame which are named the eight winds.

The Buddha said that the uninstructed people have been brown by these winds so that their heart responds to all this with happiness and sorrow, delight and despair, disappointment and satisfaction, hope and fear.

These waves of emotion carry people up and fling them down; and no sooner do we find rest, than they are in the power of a new wave again. To overcome these waves and land on a safe island in the midst of this ever restless ocean of existence, Equanimity is the boat.

Buddhist equanimity has to be based on vigilant presence of mind, not on indifferent dullness. It has to be the result of hard, deliberate training, not the casual outcome of a passing mood.

That means you are aware of the environment around you but you are not carried away by it.

Therefore, this quality of the mind has to be trained by meditation.

True equanimity, however, should be able to meet all these severe tests and to regenerate its strength from sources within. It will possess this power of resistance and self-renewal only if it is rooted in insight. Just as the Chinese saying shows "the greatest wise looks like a fool."

What is the nature of that insight? Nyanaponika summarizes it beautifully:

First, it is the clear understanding of how all these vicissitudes of life originate, and of our own true nature. We have to understand that the various experiences we undergo result from our kamma -- our actions in thought, word and deed -- performed in this life and in earlier lives.

The second insight on which equanimity should be based is the Buddha's teaching of no-self (anatta).

This doctrine shows that in the ultimate sense deeds are not performed by any self, nor do their results affect any self.

The second is difficult to understand. However, it can be superficially explained as having not thought of "I, me, my, mine".

To the degree we forsake thoughts of "mine" or "self" equanimity will enter our hearts. For how can anything we realize to be foreign and void of a self cause us agitation due to lust, hatred or grief? Thus the teaching of no-self will be our guide on the path to deliverance, to perfect equanimity.

The relationship between the four sublime states

First of all, according to Buddhism, these four sublime states should be cultivated through meditation. The Buddha says:

"Here, monks, a disciple dwells pervading one direction with his heart filled with loving- kindness, likewise the second, the third, and the fourth direction; so above, below and around; he dwells pervading the entire world everywhere and equally with his heart filled with loving- kindness, abundant, grown great, measureless, free from enmity and free from distress." (Digha Nikaya 13)

The same method of meditation is also used for other three: compassion, appreciative joy and equanimity.

According to Buddhism, developing wholesome social attitudes through practising the meditation of the Four Sublime states will bring about a change in one's personal and social life. To the extent that one can free oneself of ill will, cruelty, jealousy and desire, one will experience greater happiness with regard to oneself and in one's relations with others.

The relationship of the four

Unbounded love guards compassion against turning into partiality, prevents it from making discriminations by selecting and excluding and thus protects it from falling into partiality or aversion against the excluded side.

Compassion prevents love and sympathetic joy from forgetting that, while both are enjoying or giving temporary and limited happiness, there still exist at that time most dreadful states of suffering in the world.

Compassion prevents love and sympathetic joy from turning into states of self-satisfied complacency within a jealously-guarded petty happiness.

Compassion guards equanimity from falling into a cold indifference, and keeps it from indolent or selfish isolation.

Sympathetic joy holds compassion back from becoming overwhelmed by the sight of the world's suffering, from being absorbed by it to the exclusion of everything else.

Equanimity rooted in insight is the guiding and restraining power for the other three sublime states. It points out to them the direction they have to take, and sees to it that this direction is followed.

In these and other ways equanimity may be said to be the crown and culmination of the other three sublime states. The first three, if unconnected with equanimity and insight, may dwindle away due to the lack of a stabilizing factor.

Abbreviations

A. D.

Dhp. M.

Miln.

S.

Sn.

Vin.

Vism.

Anguttara Nikaya, Digha Nikaya, Dhammapada, Majhima Nikaya, Milindapahha, Samyutta Nikaya, Suttanipada, Vinaya,

Sources and reference

Buddharakkhita, Metta The Philosophy and Practice of Universal Love, The Wheel Publication No.

365/366, Buddhist Publication Society, 1989.

http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/bps/wheels/wheel365.html Buddhaghosa, The Path to Purification (Visuddhimagga), tr. Bhikkhu Nanamoli, Singapore:

Singapore Buddhist Meditation Centre, 1991. Read Chapter Nine. Harris, Elizabeth J. Detachment and Compassion in Early Buddhism, Bodhi Leaves BL 141.

Buddhist Pablication Society, 1997.

http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/harris/bll41.html Nanamoli, Metta The Practice of Loving Kindness As Taught by the Buddha in the Pali Canon, The

Wheel Publication No. 7, Buddhist Publication Society 1987.

http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/bps/wheels/wheel007.html Narada, The Buddha and his Teaching, read Chapter 42 'the Sublime States'.

http://www.bps.lk/bp library/bp 102s/page 42.html Nyanaponika, The Four Sublime States, The Wheel Publication No. 6, Buddhist Publication Society, 1993. http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/bps/wheels/wheel006.html Nyanaponika Thera, Natasha Jackson, C.F. Knight, L.R. Oates, Mudita The Buddha's Teaching on

Unselfish Joy, Four essays, Wheel Publication No. 170, Buddhist Publication Society, 1983.

http://www.accesstoinsight.org/lib/authors/various/wheell70.html Sraman, Gyana Ratna, "Loving Kindness Meditation in Visuddhimagga" Journal of Indian and

Buddhist Studies, Vol.53, No.l, December 2004.