Mantra - Mantra in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism

About mantras, what Buddha forbade is for using it for selfish, greedy purposes as I said. Anyway here's a brief history of Buddhist mantras: Mantra - Mantra in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism

Conze distinguishes three periods in the Buddhist use of mantra. Initially, like their fellow Indians, Buddhists used mantra as protective spells to ward of malign influences. Despite a Vinaya rule which forbids monks engaging in the Brahminical practice of chanting mantras for material gain, there are a number of protective for a group of ascetic monks. However, even at this early stage, there is perhaps something more than animistic magic at work. Particularly in the case of the Ratana Sutta the efficacy of the verses seems to be related to the concept of "truth". Each verse of the sutta ends with "by the virtue of this truth may there be happiness".

Later mantras were used more to guard the spiritual life of the chanter, and sections on mantras began to be included in some Mahayana sutras such as the White Lotus Sutra, and the Lankavatara Sutra. The scope of protection also changed in this time. In the Sutra of Golden Light the Four Great Kings promise to exercise sovereignty over the different classes of demigods, to protect the whole of Jambudvipa (the India sub continent), to protect monks who proclaim the sutra, and to protect kings who patronise the monks who proclaim the sutra. The apotheosis of this type of approach is the Nichiren school of Buddhism that was founded in 13th century Japan, and which distilled all Buddhist practice down to the veneration of the Lotus Sutra through recitation of the daimoku: "Nam myoho renge kyo" which translates as "Homage to the Lotus Sutra".

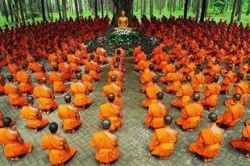

Then mantra began, in about the 7th century, to take centre stage and become a vehicle for salvation in their own right. Tantra started to gain momentum in the 6th and 7th century, with specifically Buddhist forms appearing as early as 300CE. Mantrayana was an early name for the what is now more commonly known as Vajrayana, which gives us a hint as to the place of mantra in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism. The aim of Vajrayana practice is to give the practitioner a direct experience of reality, of things as they really are. Mantras function as symbols of that reality, and different mantras are different aspects of that reality -- for example wisdom or compassion. Mantras are almost always associated with a particular deity, with one exception being the Prajnaparamita mantra associated with the Heart Sutra. One of the key Vajrayana strategies for bringing about a direct experience of reality is to engage the entire psycho-physical organism in the practices. In one Buddhist analysis the person consists of body, speech and mind. So a typical sadhana or meditation practice might include mudras, or symbolic hand gestures, or even full body prostrations; the recitations of mantras; as well as the visualization of celestial beings and visualizing the letters of the mantra which is being recited. Clearly here mantra is associated with speech. The meditator may visualize the letters in front of themselves, or within their body. They may pronounced out loud, or internally in the mind only.