More about Buddhism in China

Buddhism is based on the life and teachings of Sakyamuni, who lived in eastern India in the sixth or fifth century B.C. (roughly the same time as Confucius). He was born into royalty, and for most of his youth, led a sheltered existence within the palace. He reached a turning point in his life when he came into contact with sickness, old age, and death, and was encouraged by an ascetic to renounce his worldly life, and set out on a quest for truth, confronting the continuous cycle of birth, death, and Rebirth (Samsara) that was the fate of humanity. He sought Enlightenment at Bodh Gaya, and resolved to teach the Four Noble Truths: That life is Suffering, that Suffering is caused by craving or desire, that one must eliminate the cause of Suffering, and that this is done by following the Noble Eight-fold path leading toward morality, concentrationd Wisdom.

When Buddhism entered China centuries later, it confronted many pre-existing belief systems, including those forming around Confucian and Daoist ideas. A monastic life, for instance, seemed incongruous in a culture where male offspring were essential to maintaining the ancestral lineage. Buddhism proved to be adaptable, not only in China, but elsewhere throughout Asia, by incorporating indigenous practices and beliefs. The Buddhist concept of emptiness, for example, was explained in Daoist terms, and the commissioning of Buddhist works of art was tied to honoring family and ancestors.

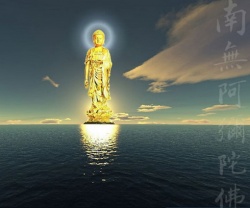

The first wave of Buddhist images that arrived in India with traders and missionaries was Indian in form and style. The Buddha was depicted seated or standing in a simple Monk's robe, with elongated ears and a cranial bump, his hands gesturing in what are called mudras. Bodhisattvas, or enlightened beings, as well as disciples (Arhats) were added as attendant figures. Over time, an interest grew in depicting other figures, including Maitreya (the future Buddha) and the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara (Guanyin in Chinese), a compassionate figure who hears the pleas of all mortal beings. By the Tang dynasty, Buddhist figures had developed along Chinese stylistic lines, although they retained many of the Indian-based symbols and meanings. New Chinese practices and beliefs were also developed, such as chan Buddhism (Japanese zen) which sought a more spontaneous, intuitive path to Enlightenment.